ACER

Maple. Deciduous trees with single or multiple trunks.

Description: Acer barbatum, Florida maple, is a small (to 25 feet in the landscape) tree with a single-trunked, rounded habit. A native of the southeastern United States, it should probably be used more widely there for its reliable fall color and heat tolerance. Zones 7–9.

A. buergeranum, trident maple, can have single or multiple trunks supporting an oval or rounded crown. It normally attains a height of 20 to 25 feet in the landscape but can grow twice as tall. Like many maples, it has three-lobed leaves borne in pairs; the lobes all point in the same direction, away from the base of the leaf. Red or orange fall color may develop in some years. The bark of trident maple is gray and brown, sometimes with orange tones, becoming scaly with age. Zones 6–7.

A. ginnala, Amur maple, grows 15 to 20 feet tall in the landscape. While most maples’ flowers are neither fragrant nor showy, Amur maple bears highly fragrant blooms in early spring. The three-lobed leaves have an extended center lobe and may turn scarlet in fall. Zones 3–7.

A. japonicum, full-moon maple, is another small (20 to 30 feet) maple with considerable landscape value. Full-moon maple’s leaves are palmately compound and nearly circular in outline. Flowers are purplish or red. Fall color is crimson and/or yellow in most years and is more reliable in Northern areas. Zones 5–8.

A. negundo, box elder, is a Northern American native often disdained for its weediness and soft wood, yet it grows in poor soil and difficult sites where most other trees can’t. It has multiple stems, a rounded crown, and a mature height of 50 to 70 feet. Yellow-green flowers appear in early spring before its compound leaves unfold; fall color is a soft yellow. Abundant winged fruits can be messy and lead to numerous seedlings. Zones 2–9.

A. palmatum, Japanese maple, normally grows 15 to 20 feet tall; its branches may spread as wide as the tree is tall, creating a layered appearance unlike the more upright form of other maples. The many cultivars offer countless options of twig and leaf color, gnarled or mounded habits, plus lacy threadleaf forms. Protect from direct wind in the North and direct sun in the South. Zones 5–8.

A. pensylvanicum is known as moosewood or striped maple. The green chalk-striped bark of this 15- to 20-foot Northeastern woodland native has considerable landscape interest. Look for yellow fall color. Striped maple performs best in cool climates under partial shade. Zones 3–6.

A platanoides, Norway maple, is a widely planted street tree with its round, dense crown; regular form; and tolerance for difficult urban conditions, such as air pollution and poor soil. It grows 40 to 50 feet tall and holds its leaves late into fall. Norway maple generally casts deep shade, making it difficult to grow turfgrass under this type of tree. It produces seedlings prolifically; because of this, it’s been classed as invasive in parts of the Northeast and central United States. Zones 4–6.

A. rubrum, red or swamp maple, is a North American native that reaches heights of 40 to 60 feet. Pyramidal in youth, red maple sprawls and arches with age. The smooth gray trunk and branches are distinctive, particularly when trees are grouped. Red flowers open before the leaves and are a softly colorful sign of spring. Fall color is bright red and/or orange. Hardiness and heat tolerance vary within the species; choose a cultivar suited to your location. Zones 3–8.

A. saccharinum, silver maple, is touted for its fast growth, but it’s also weedy and weak-wooded and may be prone to breakage. Growing 50 to 70 feet high, silver maple is upright, with spreading branches and a rounded crown; its leaves are deeply lobed and silvery beneath. The pale pink flowers appear before the leaves in spring. Look for yellows or reds in fall foliage, and a gray, furrowed trunk. Zones 3–8.

A. saccharum, sugar, rock, or hard maple, gets its names from the maple sugar derived from its rising spring sap and from the durability of its wood. It has a single trunk and a rounded crown, gray-black furrowed bark, and a mature height of 50 to 70 feet. Sugar maple’s fall color is legendary; in good years the trees turn gold, orange, and scarlet. Zones 3–7.

How to grow: With the exception of large maples, like red, sugar, silver, and Norway, used as shade trees, most maples benefit from light shade. Generous mulch and a shaded root zone are also advantages. Most maples require acid soils that are evenly moist but well drained, although red maple and box elder occur naturally on swampy sites. Given the conditions they prefer, maples are relatively problem-free trees. Scorched leaf margins may occur on trees suffering from drought or reflected heat from pavement or cars. Watch red and silver maples on high-pH soils for yellowed foliage caused by manganese deficiency. Box elders attract box elder bugs, which like to overwinter indoors. In fall, groups of these black-and-orange insects move into buildings and become household pests.

Landscape uses: Japanese, full-moon, and Amur maples make fine focal points in small-scale settings; larger areas might call for trident maple or sugar maple. Red, striped, and sugar maples are good choices for naturalizing; Norway maple, although tough, is overplanted. Use box elders for shade on difficult sites.

ACHILLEA

Yarrow. Summer- and sometimes fall-blooming perennials; herbs; dried flowers.

Description: Yarrow bears profuse 2- to 6-inch flat-topped heads of tiny flowers in shades of white, yellow, gold, pink, salmon, rust-orange, purple, and red on 2- to 5-foot stems. Soft, finely cut, aromatic foliage is green or gray.

Achillea x ‘Moonshine’ bears 3-inch soft yellow clusters on 1- to 2-foot stems atop striking, gray, dense leaves. Zones 3–8.

A. x ‘Coronation Gold’ holds its stately 3- to 4-inch golden blooms on stems 3 feet or taller over greener, looser, larger foliage. Zones 3–8.

A. millefolium, with small white flower clusters rising 1 to 2 feet above mats of ferny green leaves, has produced many colorful cultivars and hybrids. Zones 3–8.

How to grow: Plant or divide yarrows in spring or fall. Divide every 2 to 3 years to keep plants vigorous and less likely to lean over when in bloom. Plant in full sun in average, well-drained soil. Generally tough and adaptable, yarrows tolerate poor soil and drought well. In very humid regions, yarrows with gray or silvery leaves may succumb to leaf diseases within a year or two, so grow green-leaved yarrows in those areas. You may want to stake the taller cultivars, especially if you grow them in more fertile soil.

Landscape uses: The flat flower heads of yarrows provide a pleasing contrast to mounded or upright, spiky plants in a border. Try them alone in a hot, dry area. Fresh or dried, yarrows are wonderful as cut flowers. For long-lasting dried flowers, cut the heads before they shed pollen and hang them upside down in a warm, well-ventilated, sunless room.

AGERATUM

Ageratum, flossflower. All-season annuals.

Description: Ageratums bear clouds of small, fuzzy, blue, pink, or white flowers on 1-foot mounds of rather large, rough, dark green leaves. Dwarf varieties grow to only 6 inches.

How to grow: Start from seed 8 weeks before the last spring frost or buy transplants. After all danger of frost is past, set out transplants in full sun or partial shade and average soil. Space dwarf cultivars about 6 inches apart; taller ones need 10 inches.

Landscape uses: Ageratums look best massed in beds and borders or as an edging for taller plants. The blue cultivars combine beautifully with yellow marigolds.

AJUGA

Ajuga, bugleweed. Perennial groundcovers.

Description: Ajuga reptans, ajuga or common bugleweed, forms attractive dark green rosettes 2 to 3 inches wide, and spreads by runners 3 to 10 inches long. Cultivars may have bronze, purple, or variegated foliage. Sturdy blue, white, or pink flower spikes bloom in May and June, reaching 4 to 6 inches tall. Zones 4–8.

How to grow: In spring, set young plants 6 to 12 inches apart in moist, well-drained soil in full sun or partial shade. Ajugas will tolerate heavy shade but not heat or drought. Feed lightly—overfeeding encourages diseases.

Landscape uses: Use this groundcover to provide carpets of spring color. It is attractive planted under trees or along borders. Don’t plant ajuga next to your lawn unless you use a sturdy edging; the ajuga can take over.

ALCEA

Hollyhock. Summer-blooming biennials.

Description: Alcea rosea, hollyhock, is an old-fashioned favorite that bears its 3- to 5-inch rounded blooms in two forms: saucerlike singles with a central, knobby yellow column, or double puffs strongly reminiscent of tissue-paper flowers. Colors include shades of white, pink, red (sometimes so dark it appears almost black), and yellow. The blooms decorate much of the 2- to 9-foot, upright, leafy stems that rise above large masses of rounded or scalloped, rough leaves. Zones 3–8.

How to grow: Set out larger, nursery-grown plants in spring for summer bloom or smaller ones in fall for bloom next year. You can also start them from seed. Sow in midwinter for possible bloom the same year, or start them after the hottest part of summer for planting out in fall. Most hollyhocks self-sow readily if you let a few flowers go to seed. They prefer full sun to light shade in average to rich, well-drained, moist soil. Water during dry spells, and stake the taller cultivars.

Hose off spider mites and hand pick Japanese beetles, which eat both flowers and leaves. Aptly named rust disease shows up as reddish spots on the leaves and stems and can quickly disfigure or destroy a planting. Removing infected leaves and all dead leaves may help, or grow plants in out-of-the-way spots where the damage is less noticeable.

Landscape uses: Hollyhocks look their best in very informal areas such as cottage gardens, along fences and foundations of farm buildings, and on the edges of fields. Try a small group at the rear of a border.

ALL-AMERICA SELECTIONS

Since 1932, the nonprofit organization All-America Selections (AAS) has tested and evaluated vegetables and flowers to select superior cultivars that will perform well in home gardens. AAS tests new cultivars each year at more than 30 flower and 20 vegetable test gardens at universities, botanical gardens, and other horticultural facilities throughout the United States and Canada.

Each year’s new entries are grown next to past winners and standard cultivars. Winners display the All-America Selections Winner symbol on seed packets, plant labels, and in garden catalogs, alerting home gardeners to plants that are practically guaranteed to perform well in their gardens given standard care.

The judges look for flowers with attractive, long-lasting blossoms. They also evaluate uniformity, fragrance, and resistance to disease, insects, and weather stress. Vegetables are judged for yield, flavor, texture, pest resistance, space efficiency, nutritional value, and novelty effect.

Gold Medal winners are flowers and vegetables that represent a breeding breakthrough, such as ‘Sugar Snap’ peas, the first edible-podded shell pea, and ‘Profusion White’ petunia, a long-blooming, mildew-resistant cultivar that doesn’t need deadheading to continue blooming. A second tier of awards recognizes outstanding flowers and vegetables as AAS Flower, Bedding Plant, or Vegetable Award Winners.

In addition to the AAS test gardens, there are more than 200 AAS display gardens in North America. These gardens showcase past, present, and future AAS winners in a landscape setting. Visiting a display garden near you is a great way to see these plants in a garden setting and to get ideas for using them in your garden and landscape.

All-America Rose Selections (AARS) is a separate nonprofit organization that evaluates roses and has recognized outstanding new cultivars since 1938. They also recognize roses that perform superbly in specific regions of the country, so you can match your choices to your climate and conditions.

The All-America Daylily Selections Council (AADSC) is a third nonprofit organization, and it evaluates daylily cultivars at test sites all across North America. Since 1985, its experts have evaluated nearly 6,000 cultivars. Winners of the All-American Daylilies designation have performed excellently across at least five hardiness zones.

For more information on AAS, AARS, or AADSC, call or write to the organizations or visit their Web sites (see Resources on page 672).

ALLIUM

Allium, ornamental onion. Spring- and summer-blooming perennial bulbs.

Description: Don’t let the “onion” in “ornamental onion” keep you from growing these showy cousins of garlic and leeks. Their beautiful flowers more than make up for the oniony aroma they give off when bruised or cut. All bear spherical or nearly round heads of loosely to densely packed starry flowers on wiry to thick, stiffly upright stems. The grassy or straplike leaves are of little interest. In fact, the foliage on most ornamental onions starts dying back before, during, or soon after bloom and can detract from the display.

Chives in the Flower Bed

Two alliums normally confined to the herb garden make great choices for borders. Clumps of common chives (Allium schoenoprasum) add grasslike foliage and bright cotton balls of light violet flowers in Zones 3–9. Try garlic chives (A. tuberosum) in a sunny or partly shady border in Zones 4–8. Lovely 2- to 3-inch heads of white, rose-scented flowers bloom on 2-foot stems above handsome, dark green, narrow, strappy leaves in dense clumps. Cut flower stalks before garlic chives set seed, or the plants will self-sow and become weedy.

Allium aflatunense, Persian onion, bears 4-inch-wide, tightly packed, lilac globes on 2½- to 3-foot stems in mid-spring. Zones 4–8.

A. caeruleum, blue globe onion, produces 2-inch, medium blue balls on stems that rise up to 2½ feet above grassy leaves in late spring; it multiplies quickly. Zones 2–7.

A. christophii, star of Persia, bears spidery lilac flowers in spectacular globes to 1 foot wide on 1- to 2-foot stiff stems in late spring to early summer. Dried seedheads are also showy. Zones 4–8.

A. giganteum, giant onion, lifts its 4- to 6-inch crowded spheres of bright lilac flowers 3 to 4 feet or more above large, rather broad and flat leaves in late spring. Zones 4–8.

A. moly, lily leek or golden garlic, bears its sunny yellow blooms in 2- to 3-inch clusters on slightly curving, 10-inch stems in late spring. Zones 3–9.

A. oreophilum, ornamental onion, bears loose, 2-inch clusters of rose-red blooms on 6- to 8-inch stems in late spring. Zones 4–9.

A. sphaerocephalum, drumstick chives, blooms in midsummer with tiny, purple-red flowers in 2-inch oval heads on stems up to 2 feet tall above grassy foliage. Zones 4–9.

How to grow: Alliums are easy to grow in full sun or very light shade. Site them in average, well-drained soil that you can allow to become completely dry when the alliums are dormant in summer. Plant them with their tops at a depth of about three times their width. Don’t try to grow alliums in heavy clay soil. Give Persian onions, stars of Persia, and giant onions a few inches of loose winter mulch.

Landscape uses: Plant alliums in borders, cottage gardens, and among rocks. Grow them with low- or open-growing annuals and perennials, which will disguise the unsightly leaves as they die down. Combine star of Persia with tall bearded irises and old-fashioned roses for a spectacular show. Small masses of the giant onion blooming among green clouds of asparagus foliage make an unforgettable and unusual picture. All alliums last a long time as cut flowers; many also dry well in silica gel. Harvest the seed heads for arrangements before they become completely dry and brown.

AMARYLLIS

See Hippeastrum

ANEMONE

Anemone, windflower, pasque flower. Spring-blooming and late-summer- to fall-blooming tubers and perennials.

Description: Anemone blanda, Grecian windflower, produces cheerful daisylike flowers to 2 inches wide in shades of white, pink, red-violet, and blue on 3- to 6-inch plants with ferny leaves. Once established, they multiply to form low-spreading carpets. They die back completely several weeks after blooming stops in spring. Zones 4–8.

A. x hybrida, Japanese anemone, blooms in late summer and fall with 2- to 3-inch single, semidouble, or double blooms in white or shades of pink. The flowers appear on leafless stems 2 to 5 feet above mounded, cut leaves. Zones 4 (with protection) or 5–8.

A. tomentosa ‘Robustissima’ is another Japanese anemone also sold as A. vitifolia or grapeleaf anemone. Plants bear silvery pink flowers 2 feet above the foliage and are hardier than hybrids. Zones 3–8.

How to grow: In mid-fall, before planting the barklike, dead-looking tubers of Grecian windflowers, soak them in warm water overnight to plump them up. Place the tubers on their sides about 2 inches deep and no more than 4 inches apart. Choose a site where the foliage of other plants will hide the yellowing leaves in summer. Grecian windflowers thrive in a sunny to partly shady spot with average, well-drained soil containing some organic matter. Water in spring if the weather is dry. Mulch with compost or leaf mold to hold moisture in the soil and encourage self-sown seedlings to grow and produce colonies.

Divide or plant the creeping underground stems of Japanese anemones in spring. Give them partial shade or full sun if the soil is quite moist. They thrive in deep, fertile, moist but well-drained soils enriched with plenty of organic matter. Poorly drained sites, which promote rot, can be fatal in winter. Water during drought. Keep plants out of strong wind, or be prepared to stake them. Cover with several inches of oak leaves or other light mulch for the first winter in the North.

Landscape uses: Grow Grecian windflowers in masses in the light shade of tall trees or with other woodland plants and bulbs. Also try them toward the front of borders (sow sweet alyssum on top of them to hide the dying leaves), or among rocks or paving stones. Japanese anemones are glorious in borders and woodland plantings where they will colonize, providing flowers to cut.

ANIMAL PESTS

Four-footed creatures can cause much more damage than insect pests in many suburban and rural gardens. They may ruin your garden or landscape overnight, eating anything from apples to zinnias. Most animal pests feed at night, making it tricky to figure out who the culprits are.

Follow these guidelines for coping with animal pests.

Identify the pests. Ask your neighbors what kinds of wildlife are common garden marauders in your neighborhood. Sit quietly looking out a window toward your garden at dawn or dusk, when animals tend to become active. Check for droppings or paw prints around your garden, and consult a wildlife guide to identify them.

Assess the damage. If it’s only cosmetic, you may decide your plants can tolerate it. If the damage threatens harvest or plant health, control is necessary. If damage to ornamental plants is limited to one plant type, consider digging it out and replacing it with plants that are less appealing to animal pests.

Take action. Combining several tactics to deter animal pests may be most effective. For a vegetable or kitchen garden, a sturdy fence is often the only effective choice. Barriers work well to protect individual plants. Homemade or commercial repellents give inconsistent results, so use them experimentally. Scare tactics such as scarecrows and models of predator animals may frighten pest animals and birds. In extreme cases, you may choose to kill the pests by flooding their underground tunnels or by trapping or shooting. It’s up to the individual to decide if the damage is severe enough to warrant these methods. If you decide to shoot or trap any animals, check first with your state Department of Environmental Resources to learn about regulations and required permits.

Deer

Deer have a taste for a wide range of garden and landscape plants. A few deer are a gentle nuisance; in areas with high deer pressure, they can be the worst garden pest you’ll ever encounter. Deer are nocturnal, but may be active at any time. In areas where they’ve acclimated to humans, you may spot them browsing in your garden even in the middle of the afternoon.

Barriers: If deer are damaging a few select trees or shrubs, encircle the plants with 4-foot-high cages made from galvanized hardware cloth, positioned several feet away from the plants.

Fences: Fencing is the most reliable way to keep deer out of a large garden or an entire home landscape, but some types are quite costly, especially if you have it installed by a professional. Here are your options for deer fencing:

Conventional wire-mesh fences should be 8 feet high for best protection. A second, inner fence about 3 feet high will increase effectiveness because double obstacles confuse deer.

Conventional wire-mesh fences should be 8 feet high for best protection. A second, inner fence about 3 feet high will increase effectiveness because double obstacles confuse deer.

Slanted fences constructed with electrified wire are an excellent deer barrier. Installing this type of fence is a job for a professional.

Slanted fences constructed with electrified wire are an excellent deer barrier. Installing this type of fence is a job for a professional.

Deer are not likely to jump a high, solid fence, such as one made of stone or wood.

Deer are not likely to jump a high, solid fence, such as one made of stone or wood.

Polypropylene (plastic) mesh deer fencing is costly, but easier to install on your own than an electric fence.

Polypropylene (plastic) mesh deer fencing is costly, but easier to install on your own than an electric fence.

For small gardens, up to 40 feet by 60 feet, a shorter enclosure made of snow fencing or woven-wire fencing may be effective, because deer don’t like to jump into a confined space.

For small gardens, up to 40 feet by 60 feet, a shorter enclosure made of snow fencing or woven-wire fencing may be effective, because deer don’t like to jump into a confined space.

For more about deer fencing, see the Fencing entry.

Repellents: For minor deer-damage problems, repellents will be effective for awhile, but eventually the deer will probably grow accustomed to the repellent and begin browsing again. Under the pressure of a scarce food supply, deer may even learn to use the odor of repellents as guides to choice food sources. Periodically changing from one type of repellent to another can increase your chances for success. You can make your own or buy a commercial repellent.

Hang bars of highly fragrant soap from strings in trees and shrubs. Or nail each bar to a 4-foot stake and drive the stakes at 15-foot intervals along the perimeter of the area.

Hang bars of highly fragrant soap from strings in trees and shrubs. Or nail each bar to a 4-foot stake and drive the stakes at 15-foot intervals along the perimeter of the area.

Try using human hair. Ask your hairdresser to save hair for you to collect each week. Put a handful of hair in a net or mesh bag (you can use squares of cheesecloth to make bags), and hang bags 3 feet above the ground and 3 feet apart.

Try using human hair. Ask your hairdresser to save hair for you to collect each week. Put a handful of hair in a net or mesh bag (you can use squares of cheesecloth to make bags), and hang bags 3 feet above the ground and 3 feet apart.

Farmers and foresters repel deer by spraying trees or crops with an egg-water mixture. Mix 5 eggs with 5 quarts of water for enough solution to treat ¼ acre. Spray plants thoroughly. You may need to repeat application after a rain.

Farmers and foresters repel deer by spraying trees or crops with an egg-water mixture. Mix 5 eggs with 5 quarts of water for enough solution to treat ¼ acre. Spray plants thoroughly. You may need to repeat application after a rain.

Commercial repellents are available at garden centers. Be sure to ask if a product contains only organic ingredients. You may have to experiment to find one that offers good control. Watch for new products coming on the market, too. For example, preliminary tests of milk powder as a deer repellent seem promising.

Commercial repellents are available at garden centers. Be sure to ask if a product contains only organic ingredients. You may have to experiment to find one that offers good control. Watch for new products coming on the market, too. For example, preliminary tests of milk powder as a deer repellent seem promising.

Experiment with homemade repellents by mixing blood meal, bonemeal, exotic animal manure, hot sauce, or garlic oil with water. Recipes for concocting these repellents differ, and results are variable. Saturate rags or string with the mixtures, and place them around areas that need protection.

Experiment with homemade repellents by mixing blood meal, bonemeal, exotic animal manure, hot sauce, or garlic oil with water. Recipes for concocting these repellents differ, and results are variable. Saturate rags or string with the mixtures, and place them around areas that need protection.

Some gardeners who own male dogs that regularly patrol their yards report that they have few deer problems, even though they don’t have a fence or use repellents. It seems that the scent of the dogs is enough to discourage deer from spending much time in the area.

Some gardeners who own male dogs that regularly patrol their yards report that they have few deer problems, even though they don’t have a fence or use repellents. It seems that the scent of the dogs is enough to discourage deer from spending much time in the area.

Deer-proof plants: If fencing your yard is beyond your budget, and repellents aren’t doing the trick, you could try revamping your landscape with plants that deer don’t like to eat. Over time, remove the plants that deer have damaged so badly that they’ve lost their attractiveness or never flower. Replace them with shrubs, vines, and perennials with a reputation for being deer-proof. There’s no hard-and-fast list, and it’s possible that the deer in one region may dislike plants that are quite palatable to deer in another. Ask your Cooperative Extension service for a list of plants that seem to be locally deer-proof, and consult the Resources section for books on the topic.

Ground Squirrels and Chipmunks

Ground squirrels and chipmunks are burrowing rodents that eat seeds, nuts, fruits, roots, bulbs, and other foods. They are similar, and both are closely related to squirrels. They tunnel in soil and uproot newly planted bulbs, plants, and seeds. Ground squirrel burrows run horizontally; chipmunk burrows run almost vertically.

Traps: Bait live traps with peanut butter, oats, or nut meats. Check traps daily.

Habitat modification: Ground squirrels and chipmunks prefer to scout for enemies from the protection of their burrow entrance. Try establishing a tall groundcover to block the view at ground level.

Other methods: Place screen or hardware cloth over plants, or insert it in the soil around bulbs and seeds. Try spraying repellents on bulbs and seeds.

Mice and Voles

Mice and voles look alike and cause similar damage, but they are only distantly related. They are active at all times of day, year-round. They eat almost any green vegetation, including tubers and bulbs. When unable to find other foods, mice and voles will eat the bark and roots of fruit trees. They can do severe damage to young apple trees.

Barriers: Sink cylinders of hardware cloth, heavy plastic, or sheet metal several inches into the soil around the bases of trees. You may be able to protect bulbs and vegetable beds by mixing a product containing slate particles into the soil.

Traps and baits: Some orchardists place snap traps baited with peanut butter, nut meats, or rolled oats along mouse runways to catch and kill them. A bait of vitamin D is available. It causes a calcium imbalance in the animals, and they will die several days after eating the bait.

Other methods: Repellents such as those described for deer may control damage. You can also modify habitat to discourage mice and voles by removing vegetative cover around tree and shrub trunks.

Moles

In some ways, moles are a gardener’s allies. They aerate soil and eat insects, including many plant pests. However, they also eat earthworms. Their tunnels can be an annoyance in gardens and under your lawn. Mice and other small animals also may use the tunnels and eat the plants that moles have left behind.

Traps: Harpoon traps placed along main runs will kill the moles as they travel through their tunnels.

Barriers: To prevent moles from invading an area, dig a trench about 6 inches wide and 2 feet deep. Fill it with stones or dried, compact material such as crushed shells. Cover the material with a thin layer of soil.

Habitat modification: In lawns, insects such as soil-dwelling Japanese beetle grubs may be the moles’ main food source. If you’re patient, you can solve your mole (and your grub) problem by applying milky disease spores, a biological control agent, to your lawn. This is more effective in the South than in the North, because the disease may not overwinter well in cold conditions. However, if you have a healthy organic soil, the moles may still feed on earthworms once the grubs are gone.

Other methods: You can flood mole tunnels and kill the moles with a shovel as they come to the surface to escape the water. Repellents such as those used to control deer may be effective. Unfortunately, repellents often merely divert the moles to an area that is unprotected by repellents.

Pocket Gophers

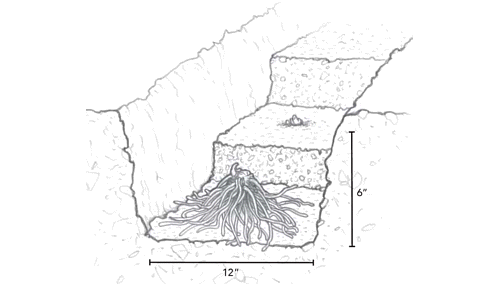

These thick-bodied rodents tunnel through soil, eating bulbs, tubers, roots, seeds, and woody plants. Fan- or crescent-shaped mounds of soil at tunnel entrances are signs of pocket gopher activity.

Fences and barriers: Exclude gophers from your yard with an underground fence. Bury a strip of hardware cloth so that it extends 2 feet below and 2 feet above the soil surface around your garden or around individual trees. A border of oleander plants may repel gophers.

Flooding: You can kill pocket gophers as you would moles, by flooding them out of their tunnels.

Rabbits

Rabbits can damage vegetables, flowers, and trees at any time of year in any setting. They also eat spring tulip shoots, tree bark, and buds and stems of woody plants.

Look, Don’t Touch

While we may wish that solving animal pest problems were as easy as posting a “Look, Don’t Touch” sign, we should heed the warning ourselves when dealing with animal pests. Wild animals are unpredictable, so keep your distance. They may bite or scratch and, in doing so, can transmit serious diseases such as rabies. Any warm-blooded animal can carry rabies, a virus that affects the nervous system. Rabies is a threat in varying degrees throughout the United States and Canada. Among common garden animal pests, raccoons and skunks are most likely to be infected. It’s best never to try to move close to or touch wild animals in your garden. And if you’re planning to catch animal pests in live traps, be sure you’ve planned a safe way to transport and release the animals before you set out the baited traps.

Fences: The best way to keep rabbits out of a garden is to erect a chicken-wire fence. Be sure the mesh is 1 inch or smaller so that young rabbits can’t get through. You’ll find instructions for constructing a chicken-wire fence in the Fencing entry.

Barriers: Erect cylinders made of ¼-inch hardware cloth around young trees or valuable plants. The cages should be 1½ to 2 feet high, or higher if you live in an area with deep snowfall, and should be sunk 2 to 3 inches below the soil surface. Position them 1 to 2 inches away from the tree trunks. Commercial tree guards are also available.

Other methods: Repellents such as those used for deer may be effective. Commercial inflatable snakes may scare rabbits from your garden.

Raccoons

Raccoons prefer a meal of fresh crayfish but will settle for a nighttime feast in your sweet corn patch. Signs that they have dined include broken stalks, shredded husks, scattered kernels, and gnawed cob ends.

Fences and habitat modification: A fence made of electrified netting attached to fiberglass posts will keep out raccoons, rabbits, and woodchucks. Or if you have a conventional fence, add a single strand of electric wire or polytape around the outside to prevent raccoons from climbing the fence. Try lighting the garden at night or planting squash among the corn—the prickly foliage may be enough to deter the raccoons.

Barriers: Protect small plantings by wrapping ears at top and bottom with strong tape. Loop the tape around the tip, then around the stalk, then around the base of each ear. This prevents raccoons from pulling the ears off the plants. Or try covering each ear with a paper bag secured with a rubber band.

Woodchucks

Woodchucks, or groundhogs, are found in the Northeast, the Mid-Atlantic, parts of the Midwest, and most of southern Canada. You are most likely to see woodchucks in the early morning or late afternoon, munching on a variety of green vegetation. Woodchucks hibernate during winter. They’re most likely to be a pest in early spring, eating young plants in your gardens.

Fences: A sturdy chicken-wire fence with a chicken-wire-lined trench will keep out woodchucks. See instructions for constructing one in the Fencing entry.

Barriers: Some gardeners protect their young plants from woodchucks by covering them with plastic or floating row covers.

Other Animal Pests

The following animals cause only minor damage to gardens or are pests only in a limited area of the country.

Armadillos: These animals spend most of the day in burrows, coming out at dusk to begin the night’s work of digging for food and building burrows. Their diet includes insects, worms, slugs, crayfish, carrion, and eggs. They will sometimes root for food in gardens or lawns. Armadillos cannot tolerate cold weather, which limits their range to the southern United States.

A garden fence is the best protection against armadillos. You also can trap them.

Prairie dogs: Prairie dogs can be garden pests in the western United States. They will eat most green plants. If they are a problem in your landscape, control them with the same tactics described for ground squirrels and pocket gophers.

Skunks: Skunks eat a wide range of foods. They will dig holes in your lawn while foraging and may eat garden plants. Skunks can be a real problem when challenged by pets or unwary gardeners.

Keep skunks out of the garden by fencing it. You can try treating your lawn with milky disease spores to kill grubs.

Squirrels: Squirrels eat forest seeds, berries, bark, buds, flowers, and fungi. Around homes, they may feed on grain, especially field corn. Damage is usually not serious enough to cause concern. Try using repellents such as those suggested for deer control to protect small areas.

Bird Pests

To the gardener, birds are both friends and foes. While they eat insect pests, many birds also consume entire fruits or vegetables or will pick at your produce, leaving damage that invites disease and spoils your harvest.

Some of the birds likely to raid your vegetable gardens are blue jays and blackbirds such as crows, starlings, and grackles. If you grow berries or tree fruit, you may find yourself playing host to beautiful but hungry songbirds such as cedar waxwings and orioles. You’ll have to decide which you enjoy more—eating the fruit or birdwatching!

Scare Tactics

Many gardeners report success in using commercial or homemade devices to frighten birds away from their crops.

Fake enemies. You can scare birds by fooling them into thinking their enemies are present. Try placing inflatable, solid, or silhouetted likenesses of snakes, hawks, or owls strategically around your garden to discourage both birds and small mammals. They’ll be most effective if you occasionally reposition them so that they appear to move about the garden. Hang “scare-eye” and hawklike balloons and kites that mimic bird predators in large plantings. Use 4 to 8 balloons per acre in orchards or small fruit or sweet corn plantings.

Weird noises. Unusual noises can also frighten birds. A humming line works well in a strawberry patch or vegetable garden. The line, made of very thin nylon, vibrates in even the slightest breeze. The movement creates humming noises inaudible to us, but readily heard and avoided by birds. Leaving a radio on at night in the garden can scare away some pests. A word to the wise: Commercially available ultrasonic devices that purport to scare animal and bird pests are unreliable.

Flashes of light. Try fastening aluminum pie plates or unwanted CDs to stakes with strings in and around your garden. Blinking lights may work, too.

Sticky surfaces. Another tactic that may annoy or scare birds is to coat surfaces near the garden where they might roost with Bird Tanglefoot.

And don’t forget two tried-and-true methods: making a scarecrow and keeping a domestic dog on your property.

In general, birds feed most heavily in the morning and again in late afternoon. Schedule your control tactics to coincide with feeding times. Many birds have a decided preference for certain crops. Damage may be seasonal, depending on harvest time of their favorite foods.

You can control bird damage through habitat management or by blocking their access or scaring them away from your garden (see “Scare Tactics”). For any method, it is important to identify the bird. A control effective for one species may not work for another. Also, you don’t want to mistakenly scare or repel beneficial birds.

Try these steps to change the garden environment to discourage pesky birds:

Eliminate standing water. Birds need a source of drinking water, and a source near your garden makes it more attractive.

Eliminate standing water. Birds need a source of drinking water, and a source near your garden makes it more attractive.

Plant alternate food sources to distract birds from your crop.

Plant alternate food sources to distract birds from your crop.

In orchards, prune to open the canopy, since birds prefer sheltered areas.

In orchards, prune to open the canopy, since birds prefer sheltered areas.

In orchards, allow a cover crop to grow about 9 inches tall. The growth will be too high for birds who watch for enemies on the ground while foraging.

In orchards, allow a cover crop to grow about 9 inches tall. The growth will be too high for birds who watch for enemies on the ground while foraging.

Remove garden trash and cover possible perches to discourage smaller flocking birds like sparrows and finches that often post a guard.

Remove garden trash and cover possible perches to discourage smaller flocking birds like sparrows and finches that often post a guard.

You can also take steps to prevent birds from reaching your crops. The most effective way is to cover bushes and trees with lightweight plastic netting, and to cover crop rows with floating row covers (see Row Covers, page 518).

ANNUALS

When gardeners think of annuals they think of color, and lots of it. Annuals are garden favorites because of their continuous season-long bloom. Colors run the spectrum from cool to hot, subtle to shocking. Plants are as varied in form, texture, and size as they are in color.

In the strictest sense, an annual is a plant that completes its life cycle in one year—it germinates, grows, flowers, sets seed, and dies in one growing season. Gardeners don’t stick to the strict botanical definition of the term, however, and use the term annual to describe any plant that will bloom well in the same year it is planted and then die after exposure to end-of-season frosts or freezes. Within the realm of annuals, there are plants that can tolerate cold temperatures, ones that can’t stand a whisper of frost, and others that are actually shrubs or perennials. Many popular plants we grow as annuals are actually tender perennials, including wax or semperflorens begonias (Begonia × semperflorens-cultorum), impatiens (Impatiens wallerana), lantana (Lantana camara), and zonal geraniums (Pelargonium spp.). We treat them as annuals because they’re not hardy in most climates and are killed by winter’s cold and replaced each season.

Annuals have as many uses as there are places to use them. They are excellent for providing garden color from early summer until frost. They fill in gaps between newly planted perennials. They are popular cut flowers. Annuals can make even the shadiest areas of the late-summer garden brighter. And since you replace them every year, you can create new designs with different color schemes as often as you want.

There are hundreds of great annuals for home gardens, more than could possibly be described on these pages. Since matching plant to site is one of the most important considerations in choosing which annuals to grow, start by consulting the lists of annuals for different kinds of sites (shade, wet soil, etc.) throughout this entry. Then, to learn more about specific plants on those lists, refer to the Quick Reference Guide on page 676 to see which specific annuals are described elsewhere in this book. Also check the Resources section on page 672 for titles of some excellent books that offer extensive information on annuals.

KEY WORDS Annuals

Hardy annual. An annual plant that tolerates frost and self-sows. Seeds winter over outside and germinate the following year. Examples: globe candytuft (Iberis umbellata), cleome (Cleome hassleriana).

Half-hardy annual. An annual plant that can withstand light frost. Seeds can be planted early. Plants can be set out in fall and will bloom the following year. Often called winter annual. Examples: pansies (Viola × wittrockiana), sweet peas (Lathyrus odoratus).

Tender annual. Also called a warm-weather annual, these are annual plants from tropical or subtropical regions, easily killed by light frost. The seeds need warm soil to germinate. Most annuals are in this category. Examples: marigolds (Tagetes spp.), petunias (Petunia spp.), zinnias (Zinnia spp.).

Tender perennial. A plant that survives more than one season in tropical or subtropical regions, but that is easily killed by light frost. Examples: coleus (Solenostemon scutellarioides), Persian shield (Strobilanthes dyerianus).

Landscaping with Annuals

Annuals are beautiful additions to the home landscape. You can use them alone or in combination with other kinds of plants. Bedding out is the traditional way of using annuals. The Victorians created extensive, colorful displays, usually with intricate patterns of closely spaced, often very low-growing annuals set against emerald lawns, called bedding schemes. That’s why annuals are often called bedding plants.

When designing with annuals, remember that a little color goes a long way. Bright oranges, pinks, and reds may clash. Choose annuals with care, and make sure you create a pleasing color combination. See the Garden Design entry for ideas on how to visualize your garden and create a design. Here are some of the best ways to landscape with annuals.

Annual Plantings

You can take a tip from Victorians and create formal or informal designs with annuals in island beds or in borders. Fences, hedges, and brick or stone walls all make attractive backdrops for annual gardens. Arrange annuals in drifts for maximum color impact from their flowers. Also don’t forget to include some plants that have spectacular foliage such as coleus and cannas (Canna × generalis).

An annual garden is a great opportunity to try out a color scheme—hot colors with brilliant oranges and fiery reds and yellows, for example, or a design with all soft pastels. This will help you determine within a single season if a particular scheme works for you. In addition to the generic seed packets of mixed-color annuals offered at most nurseries, catalog and Internet seed specialists offer many popular annuals in packets of individual colors. These allow you the option to buy and grow only white zinnias, cleome, and marigolds, for example.

Annuals are also a good choice for outlining or edging garden spaces. Compact growers like wax begonias, creeping zinnia (Sanvitallia procumbens), and edging lobelia (Lobelia erinus) make fine edgings for garden beds.

Annuals are popular for cutting because they flower enthusiastically throughout the growing season. Grow them in a special cutting garden or mix with other flowers. See Cut Flower Gardening on page 187.

Perennial and Mixed Plantings

Annuals are a wonderful choice for adding color to a perennial garden, and they’re especially valuable for summer color after popular perennials like peonies have finished blooming for the season. Some gardeners leave unplanted spaces in their perennial gardens specifically for filling with annuals along with tender perennials like cannas and dahlias. You can also sprinkle seed of annuals such as larkspur (Consolida ajacis) or cleome (Cleome hassleriana) between clumps of perennials. Or consider planting giant-size annuals such as sunflower (Helianthus annuus) or Mexican sunflower (Tithonia rotundifolia) along the back of a border or between shrubs.

Annuals also are valuable for helping a new perennial garden look its best while it is getting established. Since many perennials are slow-growing by nature, the average perennial garden takes up to three years to look its best. Annuals are perfect for carrying the garden through the first few seasons. Fill in the gaps between those slowpoke plants with the tall spikes of snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), flowering tobacco (Nicotiana alata), and blue cupflower (Nierembergia hippomanica var. violacea). Take care not to crowd or overwhelm the permanent plants—try mid-season pruning or staking of overly enthusiastic annuals.

Other annuals that are perfect for mixed plantings are annual ornamental grasses, including big quaking grass (Briza maxima), purple fountain grass (Pennisetum setaceum ‘Purpureum’), hare’s-tail grass (Lagurus ovatus), and Job’s tears (Coix lacryma-jobi). They add elegance to the garden, with clean, simple lines and soft textures. Annual grasses are wonderful to combine with bold-textured plants like Sedum ‘Autumn Joy’ and coneflowers (Rudbeckia spp.). Annual grasses are especially valuable for cutting and drying.

Shade Gardens

Annuals can play an important role in brightening up shade in woodland gardens, where flowers are hard to come by after spring wildflowers fade. You can fill a shaded spot entirely with annuals—impatiens and wax begonias are two popular choices—but they’re even more effective when combined with shade-loving perennials. A moist, shaded spot that glows with multicolored impatiens set off by ferns and hostas is a welcome summer sight. See page 44 for a list of plants that will perk up shady areas.

If your shaded site is created by shallow-rooted trees like maples, which make it impossible to dig or plant a garden, don’t despair. Instead, fill large tubs or containers with potting soil, and plant them with impatiens, begonias, browallias, coleus, and other shade-loving annuals. Use caladiums, begonias, or wishbone flowers (Torenia fournieri) in pots around a shaded patio or deck. Caladiums are also nice under trees to perk up beds of pachysandra and other groundcovers. Add spring color to shaded sites with pansies. Begonias or impatiens make a colorful edging for a shaded patio or walk. Blue-flowered browallias are great for a formal border in the dappled shade at the edge of a lawn.

Annuals for Shade

If trees, walls, or buildings on your property dictate that shaded beds and borders are your lot in life, don’t despair. Count on cheerful annuals to perk things up. The jewel-like tones of impatiens or coleus will brighten even the darkest areas under trees. It’s surprising how many annuals do tolerate shade. Plants in this list will grow in partial shade. An asterisk (*) indicates a plant that will tolerate full shade.

Anchusa capensis (summer forget-me-not)

Begonia × semperflorens-cultorum (wax begonia)

Browallia spp. (sapphire flowers)

Caladium × hortulanum (caladium)

Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar periwinkle)

Colocasia esculenta (elephant’s ear)

Hypoestes phyllostachya (polka-dot plant)

Impatiens wallerana (impatiens)*

Lobelia erinus (lobelia)

Mimulus × hybridus (monkey flower)

Myosotis sylvatica (forget-me-not)

Nemophila menziesii (baby-blue-eyes)

Nicotiana alata (flowering tobacco)

Nierembergia hippomanica var. violacea (blue cupflower)

Omphalodes linifolia (navelwort)

Perilla frutescens (perilla)

Salvia splendens (scarlet sage)

Solenostemon scutellarioides (coleus)*

Thunbergia alata (black-eyed Susan vine)

Torenia fournieri (wishbone flower)*

Viola tricolor (Johnny-jump-ups)

Viola × wittrockiana (pansy)

Trellises and Posts

Annual vines make fast-growing screens, providing privacy and shade. Use them to help create garden rooms or to hide unattractive views or utility areas such as garden workstations or compost bins. These vines don’t need a formal trellis or extensive training. You can cover a pillar or lamppost with chicken wire for quick and easy support. Store the wire at the end of the season. Or, they can easily climb strings suspended from an overhead pole or wire. Branches made into a tepee frame make a unique trellis, too. Garden centers even sell collapsible trellises that can be moved from place to place for a temporary screen. Annual vines also are excellent choices for training up shrubs, and they let you add summer flowers to an otherwise humdrum all-green hedge.

A fence festooned with bright blue morning glories is a beautiful sight. But if you think about it, what would the morning glory be without its bright green, heart-shaped foliage, especially in the afternoon when the flowers fade? Don’t neglect foliage when you select annual vines. Cardinal climber (Ipomoea × multifida) has lacy fingerlike foliage, while the round foliage of nasturtiums is attractive and edible, too.

Annuals with Striking Foliage

These annuals all have outstanding foliage. Some, like wax begonias, zonal geraniums, and morning glories, also produce cheerful flowers. Use foliage annuals to complement annuals grown for flowering display, or as accents on their own.

Alternanthera ficoidea (copperleaf)

Amaranthus tricolor (Joseph’s-coat)

Atriplix hortensis (orach, mountain spinach)

Bassia scoparia f. trichophylla (summer cypress)

Begonia × semperflorens-cultorum (wax begonia)

Beta vulgaris (Swiss chard)

Brassica oleracea (ornamental kale)

Caladium × hortulanum (caladium)

Canna × generalis (canna)

Euphorbia marginata (snow-on-the-mountain)

Foeniculum vulgare ‘Redform’ (ornamental fennel)

Hibiscus acetosella (mallow)

Hypoestes phyllostachya (polka-dot plant)

Ipomoea batatas (ornamental sweet potatoes)

Iresine spp. (bloodleafs, beefsteak plants)

Ocimum basilicum (basil)

Pelargonium × hortorum (zonal geranium)

Perilla frutescens (perilla)

Ricinus communis (castor bean)

Senecio cineraria (dusty miller)

Solenostemon scutellarioides (coleus)

Strobilanthes dyeranus (Persian shield)

Tradescantia pallida ‘Purpurea’ (purple heart)

Zea mays ‘Variegata’ (ornamental corn)

Many vines combine flowers, foliage, and showy fruits. Gourds (Lagenaria spp.) are very decorative. Their huge yellow flowers are edible, and the multicolored fruits have many craft uses. Scarlet runner beans (Phaseolus coccineus) combine handsome foliage, pretty flowers, and edible beans. Whatever your gardening style may be, annual vines deserve a place scrambling up a trellis, post, or pillar.

See above for a list of plants to try.

Containers

Annuals are perfect container plants. Their fast growth, easy culture, and low cost make them irresistible for pots, window boxes, and planters. Best of all, you can create decorative container gardens quickly—especially if you start with large-size annuals—and move them around the garden to mix and match your display.

Select as large a container as you can comfortably manage. Small containers dry out far too quickly and create extra work. Choose a light soil mix that drains well but holds moisture. There are two schools of thought when it comes to planting. Some gardeners are careful not to overplant. Annuals grow fast and will quickly fill a container. Other gardeners plant containers fairly thickly because they like the look of all the different shapes and colors growing together. Crowded plants won’t bloom as well as plants that are given more space, and they will require more watering. Fertilize containers regularly with a balanced organic fertilizer. (See Fertilizers for choices.)

Annual Vines

Whether they are trained onto a trellis, over a fence, or up a pole, all of the following vines add interest and appeal to gardens. All prefer full sun.

Cardiospermum halicacabum (balloon vine, love-in-a-puff)

Cobaea scandens (cup-and-saucer vine, cathedral bells)

Cucurbita pepo (miniature pumpkin)

Humulus japonicus ‘Variegatus’ (variegated Japanese hops)

Ipomoea alba (moonflower)

Ipomoea quamoclit (cypress vine, star glory)

Ipomoea tricolor (morning glory)

Lablab purpureus (hyacinth bean)

Lathyrus odoratus (sweet pea)

Mandevilla × amoena ‘Alice DuPont’ (mandevilla)

Maurandya scandens (chickabiddy, creeping gloxinia)

Phaseolus coccineus (scarlet runner bean)

Rhodochiton atrosanguineum (purple bell vine)

Solanum jasminoides (potato vine)

Thunbergia alata (black-eyed Susan vine)

Tropaeolum majus (nasturtium)

Tropaeolum peregrinum (canary vine)

You can start container gardening in early spring with pansies. Summer and fall bring endless choices for sun or shade. Fill containers with a single species—all red zonal geraniums, for example—or create gardens with a number of different annuals. One good way to compose an attractive arrangement is to include four kinds of plants: flags, fillers, accents, and trailers. Flags are tall plants that give the composition height, such as ornamental grasses and cannas. Fillers bring handsome fine-textured foliage and/or small flowers to the mix, and include curry plant (Helichrysum italicum spp. serotinum), polka-dot plant (Hypoestes phyllostachya), and even basil (Ocimum basilicum). Accent plants feature bold, eye-catching foliage or flowers and include ornamental peppers (Capsicum annuum), dwarf dahlias, or zonal geraniums. Finally, trailers spill over the edge of the pot to add a charming frame with either pretty leaves or bright flowers. Trailers include bacopa, edging lobelia (Lobelia erinus), and petunias.

For fall containers, ornamental kales and cabbages, zonal geraniums, and snapdragons remain attractive until hard frost. Tender annuals such as coleus, begonias, and lantanas can also be pruned and brought indoors for winter.

Hanging baskets were made for annuals. They signal the arrival of summer. Use seasonal displays of fuchsias, ivy geraniums (Pelargonium peltatum), trailing lantana (Lantana montevidensis), and trailing petunias to highlight a porch, breezeway, or gazebo. Grow plants singly or in combination to create eye-catching displays. Vines are especially nice in hanging baskets and are easily controlled. Choose a medium-weight potting soil that holds moisture. Remember to water often. In midsummer, baskets may need watering two to three times a day. Fertilize regularly with a balanced organic fertilizer. See the Container Gardening entry for more information on growing annuals in containers.

Choosing What to Buy

With so many different species and cultivars on the market, you’d think it would be impossible to decide which plants to buy. It’s easier to narrow your choices if you keep a checklist of what you’re looking for and stick to it.

First, choose plants that match your garden design: If you need a tall plant with pastel flowers, don’t be swayed by a flat of endearing French marigolds. Think of it as a simple rule: Don’t buy plants unless you have a place for them. This will save you money and frustration, and your garden will look a lot better for your restraint.

Next, when it comes to which particular cultivar to buy, look at the mature size, rate of growth, how long it takes to bloom, and special considerations (for example, you may not like heavily veined petals). Most annuals are easy to grow from seed, and there are good reasons to raise your own seedlings. For one thing, you’ll have many more cultivars to choose from if you buy seed instead of plants, because mail-order catalogs and Internet suppliers offer more choices than garden centers do. And when you grow your own seedlings, you can do so organically, which most commercial producers of annual bedding plants don’t.

Growing Your Own Annuals

It’s better to start most annual seeds in pots or flats indoors rather than to direct-seed in the garden. Indoor planting gives you more predictable results. Out in the garden, wind, rain, insects, slugs, compacted soil, and other hazards often combine to reduce seed germination and seedling survival below acceptable levels. There is one advantage to direct-seeding, though. With so many gardening chores, you may welcome the opportunity to get things into the ground and be more or less done with them.

When you’re deciding whether to sow annual seeds indoors or out, remember that direct-seeding in the garden works best with larger seeds that are less likely to be washed away or buried too deeply. Also, certain plants like poppies, morning glories, and sweet peas don’t like to be disturbed and should always be sown directly where they are to grow. For seed-starting basics, along with information on sowing seed outdoors in the garden, see the Seed Starting and Seed Saving entry.

Self-sowing annuals: Some annuals such as portulaca, spider flower, and browallia may self-sow in the garden after the first year you plant them. Their seeds survive winter and germinate in spring when the soil warms up. If seedlings grow in the right place, you have it made. But more than likely you’ll have to transplant your volunteers to the spot where you want them to grow.

Saving seeds: Certain annuals such as cosmos, sweet peas, and ornamental grasses produce seeds that you can collect and sow the next year. However, most annuals are hybrids and will not come true from seed.

Annuals for Dry Sites

Unlike most annuals, these plants are adapted to dry soils. Grow them in areas you don’t want to water often, or in beds where the soil stays very dry.

Amaranthus tricolor (Joseph’s-coat)

Arctotis stoechadifolia (African daisy)

Bassia scoparia (summer cypress)

Centauria cyanus (cornflower)

Convolvulus tricolor (dwarf morning glory)

Coreopsis tinctoria (calliopsis)

Dimorphotheca sinuata (cape marigold)

Dorotheanthus bellidiformis (livingstone daisy)

Dyssodia tenuiloba (Dahlberg daisy)

Eschscholzia californica (California poppy)

Euphorbia marginata (snow-on-the-mountain)

Eustoma grandiflorum (prairie gentian, formerly Lisianthus russellianus)

Felicia spp. (blue marguerites)

Gazania spp. (treasure flowers)

Gomphrena globosa (globe amaranth)

Limonium spp. (statices, sea lavenders)

Lobularia maritima (sweet alyssum)

Mirabilis jalapa (four-o’clock)

Pennisetum setaceum (fountain grass)

Portulaca grandiflora (moss rose)

Salvia spp. (sages)

Sanvitalia procumbens (creeping zinnia)

Senecio cineraria (dusty miller)

Tithonia rotundifolia (Mexican sunflower)

Verbena × hybrida (garden verbena)

New plants from cuttings: You can grow many annuals easily from cuttings. A cutting is a portion of the stem that is cut off and rooted to form a new plant. Take cuttings from tender perennials that are grown as annuals. Coleus, begonias, geraniums, fuschias, and impatiens are some common annuals that root easily. Cuttings are a great way to save a favorite color of coleus or rejuvenate an old geranium that has gotten too big for its container. Taking cuttings also saves you money—because they’re a virtually free source of new plants for planting out next year. See the Cuttings entry for directions on taking and rooting cuttings.

Planting

The first warm days of spring draw droves of gardeners to the nurseries. It’s tempting to buy annuals early and get them into the ground. While early shopping may be advisable to ensure the best selection, don’t be too hasty. Know the last spring frost date for your area, and don’t plant tender annuals out in the garden until after this date. When buying annuals, be aware that plants raised and kept in greenhouses will need to be hardened off before they can be safely planted in the garden unless the weather has already warmed up and temperatures have settled. See the Transplanting entry for directions for hardening off seedlings.

Planting is easy in well-prepared soil. The majority of annuals prefer a loamy soil that’s well drained and moisture retentive, with plenty of organic matter. See the Soil entry on page 550 for more information on getting a bed ready to grow annuals.

With cell packs, push out the plant from below into your waiting hand. The roots will usually be tightly packed in the ball of soil. You can pop them in the ground as is, and studies have shown that they’ll probably do just fine. If roots are very tightly packed, though, don’t be afraid to break them up a bit—make shallow cuts along the outside of the root ball with a sharp knife, or loosen the roots with your fingers. This encourages roots to grow out into the surrounding soil and prevents the plants from becoming stunted. Fast-growing annuals quickly recover from the shock of transplanting.

Remove the rims and bottoms of peat pots before planting. If there are not too many roots sticking through, remove the whole pot. This allows maximum contact between the garden soil and the potting soil. Slice the outside of peat pellets in at least three places to cut the net that encircles them.

Take plants out of flats or pots one at a time so the root balls won’t dry out from exposure. If the soil in the flats is dry, water the plants before planting. Be careful not to plant too deeply—set out your plants at the same depth as they were growing in the flat or pot. Firmly pack the soil around the stem. Water thoroughly and deeply as soon as planting is done. Avoid planting during the heat of the day, or plants may wilt and die before you get water to them.

If you’re planting a formal design, you’ll want the annuals spaced evenly in your bed or border. Use a yardstick or make a spacing guide by marking a board at 2-inch intervals. Common spacing for most annuals is 10 to 12 inches apart.

Informal designs do not require such careful attention to placement, and spacing can be estimated using the length of your trowel as a guide.

Annuals for Damp Sites

If you’re trying to garden in a low area where conditions stay fairly boggy, don’t despair. You can grow some of the most beautiful annuals on a damp site. One of the most striking annuals of all—the towering castor bean—doesn’t mind wet feet. All the annuals in this list tolerate moist soil. An asterisk (*) indicates a plant that thrives in very moist soil.

Caladium × hortulanum (caladium)

Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar periwinkle)

Cleome hasslerana (spider flower)

Exacum affine (Persian violet)

Hibiscus spp. (mallows)

Impatiens wallerana (impatiens)

Limnanthes douglasii (meadow foam)*

Mimulus × hybridus (monkey flower)*

Myosotis sylvatica (forget-me-not)*

Ricinus communis (castor bean)

Solenostemon scuttellarioides (coleus)*

Torenia fournieri (wishbone flower)

Viola × wittrockiana (pansy)

Maintaining Annuals

If you’ve prepared the soil well before planting, maintenance chores are pretty basic. Keep the soil evenly moist throughout the growing season. An inch of water per week is standard for most garden plants, though some annuals will thrive in drier soils.

SMART SHOPPING

Annuals

A smart shopper never leaves home without a list—choose the annuals you want to grow and know how many you need before you get to the garden center. Then, before you buy, check the plants carefully, keeping these guidelines in mind:

- Make sure the plants are well rooted. Gently tug on the stem; a plant with damaged or rotten roots will feel loose.

- Choose lush but compact plants.

- Avoid leggy and overgrown plants. The crown should be no more than three times the size of the container.

- Never buy wilted plants. Under-watering weakens plants and slows establishment.

- Check for insects on the tops and undersides of leaves and along stems.

- Avoid plants with yellow or brown foliage. They have either dried out or have disease problems.

- Don’t buy big plants. They are expensive, and smaller plants will quickly catch up once they are planted.

Buying seeds is easier, since seed quality is usually the same for all companies, but keep these hints in mind:

- Compare costs of seeds from different companies and check seed counts per package.

- Buy seeds by named variety or cultivar so you’ll get exactly what you want.

- Check the date on the back of the package. Make sure you buy fresh seeds.

- Mail ordering requires trust, so start small. Order from a few companies, and see which seeds give the best results.

- Avoid special deals and unbeatable bargains.

Weeding is important in any garden, and the annual garden is no exception. Turning the soil for planting is likely to uncover weed seeds. Regular hand weeding will ensure that annuals aren’t competing with weeds for light, moisture, and fertilizer. Frequent cultivation helps control seedling weeds and breaks up the soil surface, allowing water to penetrate. Put down a light mulch that allows good water infiltration to help conserve water and keep down weeds. Shredded leaves, buckwheat hulls, cocoa shells, and bark mulch are good choices.

Today many annual hybrids have been selected for compact growth, so you usually won’t have to pinch and stake them. However, some older cultivars and annuals grown for cut flower production may need staking. Tall plants such as ‘Rocket’ snapdragons and salpiglossis may need staking, especially in areas with strong winds or frequent thunderstorms. Many annuals benefit from thinning or disbudding. This will increase flower size and stem strength. Removing spent flowers keeps annuals in perpetual bloom. If you want to save seed, stop deadheading in late summer to allow ample seed set. Remove yellowing foliage during the growing season to keep down disease. If plants get too dense, remove a few of the inner stems to increase air circulation and light penetration.

Coping with Problems

Annuals are a tough group of plants, but they can suffer from some pest and disease problems. The best way to avoid problems is with good cultural practices, good maintenance, and early detection. Healthy plants develop fewer problems. Here are a few simple tips:

Water early in the day to enable plants to dry before evening. This helps prevent leaf spot and other fungal and bacterial problems.

Water early in the day to enable plants to dry before evening. This helps prevent leaf spot and other fungal and bacterial problems.

Don’t overwater. Waterlogged soil is an invitation to root-rot organisms.

Don’t overwater. Waterlogged soil is an invitation to root-rot organisms.

Remove old flowers and yellowing foliage to destroy hiding places for pests.

Remove old flowers and yellowing foliage to destroy hiding places for pests.

Remove plants that develop viral infections and dispose of them.

Remove plants that develop viral infections and dispose of them.

Never put diseased plants in the compost.

Never put diseased plants in the compost.

Early detection of insects means easy control.

Early detection of insects means easy control.

Many insects that attack annuals can be controlled by treating the plants with a spray of water from a hose. Treat severe infestations with an appropriate organic spray or dust. Follow label recommendations. For more on natural pest and disease control, see the Pests and Plant Diseases and Disorders entries.

Many insects that attack annuals can be controlled by treating the plants with a spray of water from a hose. Treat severe infestations with an appropriate organic spray or dust. Follow label recommendations. For more on natural pest and disease control, see the Pests and Plant Diseases and Disorders entries.

ANTIRRHINUM

Snapdragon. Summer- and fall-blooming annuals.

Description: Snapdragons have flowers in all major colors except blue, plus bicolored and tricolored flowers. Most snapdragons bear the typical “little dragon mouth” flowers, but there are also single, open (penstemon-flowered) and double (azalea-flowered) cultivars. Upright cultivars grow 1 to 3 feet tall, with long flower spikes atop stiff stems bearing small leaves. Dwarf cultivars grow 4 to 12 inches tall with almost equal spread.

How to grow: Sow seeds of taller cultivars indoors 8 to 10 weeks before the last spring frost for bloom beginning in midsummer, or in late spring for plants to winter over in Zones 7 and warmer for bloom late next spring. You also can buy transplants for setting out after hard spring frosts. Pinch plants when they are 3 to 4 inches tall for more bloom spikes. Stake them as they grow or pile up to 4 inches of soil around the base of the plants. After bloom, cut plants back halfway, and feed them for a second bloom. Sow seeds of dwarf cultivars indoors a month before the last frost, or sow directly outdoors after the danger of hard frost is past. When sowing snapdragons, press the seeds onto the soil surface and do not cover them, since they need light to germinate.

Snapdragons provide color all season and beyond light frosts in fall. They do best in a sunny spot with light, sandy, humus-rich soil with a neutral pH. Rust, a fungal disease, can cause brown spots on leaves, flowers, and stems, followed by wilting and death of the plant. Grow only rust-resistant cultivars.

Landscape uses: Grow the tall cultivars in a cutting garden for superb cut flowers, but don’t overlook their temporary use as tall spikes in beds and borders. Dwarf forms make colorful groundcovers and fill gaps left by withering bulb foliage.

APPLE

Malus pumila and other spp.

Rosaceae

Biting into a crisp apple picked fresh from your own tree is like eating sweet corn straight from your garden. You may never taste anything quite so delicious. Growing apples organically takes perseverance, but it can be done. Apple trees come in a wide range of sizes to suit any yard and make good landscape trees.

Selecting trees: Since apple trees take three or more years after planting to bear fruit, it pays to select trees carefully. Here are some factors to keep in mind:

Apples are subject to many serious diseases such as apple scab. Choose resistant cultivars; new ones are released every year. ‘Enterprise’ and ‘Liberty’ are immune to apple scab and resistant to cedar apple rust, powdery mildew, and fire blight.

Apples are subject to many serious diseases such as apple scab. Choose resistant cultivars; new ones are released every year. ‘Enterprise’ and ‘Liberty’ are immune to apple scab and resistant to cedar apple rust, powdery mildew, and fire blight.

Apple trees can be very large or quite compact, depending on whether they’re standard, semidwarf, or dwarf. Standard trees can reach 30 feet and take from 4 to 8 years to bear first fruit. Most home gardeners prefer dwarf and semidwarf trees, which are grafted on a rootstock that keeps them small. These trees grow 6 to 20 feet tall (depending on the rootstock used) and produce full-sized apples in just a few years. See “A Range of Rootstocks” on page 54 for more information on advantages and disadvantages of various rootstocks. The final height of your tree will also depend on which cultivar you select, because some cultivars are more compact than others. Growing conditions and pruning and training techniques also affect mature height. ‘Haralson’ and ‘Honey Gold’ have a strong, horizontal branching habit, making them easy for beginners to prune.

Apple trees can be very large or quite compact, depending on whether they’re standard, semidwarf, or dwarf. Standard trees can reach 30 feet and take from 4 to 8 years to bear first fruit. Most home gardeners prefer dwarf and semidwarf trees, which are grafted on a rootstock that keeps them small. These trees grow 6 to 20 feet tall (depending on the rootstock used) and produce full-sized apples in just a few years. See “A Range of Rootstocks” on page 54 for more information on advantages and disadvantages of various rootstocks. The final height of your tree will also depend on which cultivar you select, because some cultivars are more compact than others. Growing conditions and pruning and training techniques also affect mature height. ‘Haralson’ and ‘Honey Gold’ have a strong, horizontal branching habit, making them easy for beginners to prune.

Apple trees bear fruit on short twigs called spurs, but some cultivars are also available as nonspur types that produce fruit directly along their branches. Spur-bearing cultivars produce more heavily in a single season than nonspur trees do, but nonspur trees may have a longer productive life.

Apple trees bear fruit on short twigs called spurs, but some cultivars are also available as nonspur types that produce fruit directly along their branches. Spur-bearing cultivars produce more heavily in a single season than nonspur trees do, but nonspur trees may have a longer productive life.

Most cultivars need to be pollinated by a second compatible apple or crabapple that blooms at the same time. You’ll need to plant the pollinator tree within 40 to 50 feet of the tree you want it to pollinate. Some cultivars, such as ‘Mutsu’ and ‘Jonagold’, produce almost no pollen and cannot serve as pollinators. If you have space for only one tree, improve fruit set by grafting a branch of a suitable pollinator onto the tree.

Most cultivars need to be pollinated by a second compatible apple or crabapple that blooms at the same time. You’ll need to plant the pollinator tree within 40 to 50 feet of the tree you want it to pollinate. Some cultivars, such as ‘Mutsu’ and ‘Jonagold’, produce almost no pollen and cannot serve as pollinators. If you have space for only one tree, improve fruit set by grafting a branch of a suitable pollinator onto the tree.

Consider your climate, because some cultivars and rootstocks are hardier than others. Your tree will produce more fruit and live longer if it is suited to your area. ‘Alkemene’ and ‘Fiesta’, for example, are well adapted to coastal Northwest areas.

Consider your climate, because some cultivars and rootstocks are hardier than others. Your tree will produce more fruit and live longer if it is suited to your area. ‘Alkemene’ and ‘Fiesta’, for example, are well adapted to coastal Northwest areas.

Antique apples can be fun to grow but require careful selection because many are susceptible to diseases. Since many were selected for keeping quality, not flavor, taste before you plant.

Antique apples can be fun to grow but require careful selection because many are susceptible to diseases. Since many were selected for keeping quality, not flavor, taste before you plant.

Taste-test a variety of apples from local farmer’s markets and orchards before you decide what to grow. The range of aroma, taste, flesh texture, shape, color, and size of apples is far greater than a trip to your local supermarket would ever begin to suggest. Consider keeping quality too. ‘Fuji’, ‘Granny Smith’, ‘Mutsu’, and ‘Newtown Pippin’ are varieties that keep their fresh-picked quality for months, while ‘Jonathan’ and some other varieties begin to lose quality within weeks.

Taste-test a variety of apples from local farmer’s markets and orchards before you decide what to grow. The range of aroma, taste, flesh texture, shape, color, and size of apples is far greater than a trip to your local supermarket would ever begin to suggest. Consider keeping quality too. ‘Fuji’, ‘Granny Smith’, ‘Mutsu’, and ‘Newtown Pippin’ are varieties that keep their fresh-picked quality for months, while ‘Jonathan’ and some other varieties begin to lose quality within weeks.

Planting: Buy dormant 1-year-old unbranched grafted trees, sometimes called whips. Plant apples in the early spring in most areas, or in late fall in the Deep South. Space standard trees 20 to 30 feet apart, semidwarfs 15 to 20 feet, and dwarfs 10 to 15 feet. Start training immediately.

The Fruit Trees entry covers many important aspects of growing apples; refer to it for instructions on planting, pruning, and care.

Fertilizing: Healthy apples grow 8 to 12 inches per year. Have the soil tested if growth is less. Low levels of potassium, calcium, or boron may cause reduced growth and poor-quality fruit.

Apples thrive with a yearly mulch of 2 inches of compost. Cover crops of buckwheat and fava beans are good, too. They provide weed control, encourage beneficial insects, and help improve soil structure.

Apples also benefit from foliar feeding. Spray seaweed extract when the buds show color, after the petals fall, and again when young fruits reach ½ to 1 inch diameter to improve yields. If testing shows calcium is low, spray 4 more times at 2-week intervals. Gypsum spread on the soil also raises calcium levels.

Pruning: Begin training your trees to a central leader shape immediately after planting. Prune trees yearly, generally in late winter or early spring. Illustrated instructions for the central leader system are on page 245.