BABY’S-BREATH

See Gypsophila

BALLOON FLOWER

See Platycodon

BAMBOO

For many people, the word bamboo conjures up images of dense thickets of rampant spreading canes. While this is true of many types of bamboo, some species are not invasive. Evergreen members of the grass family, bamboos range from petite miniatures to massive giants. There are over 100 species of bamboo, found from the tropics to mountaintops. While most bamboos are tropical or subtropical, there are hardy bamboos that can survive temperatures of –10° to –20°F.

There are two main types of bamboos: running and clumping. Running types send out far-reaching rhizomes and can colonize large areas. Control running bamboos with 3- to 4-foot-deep barriers of sheet metal or concrete, or routinely cut off new shoots at ground level. Clumping types stay in tight clumps that slowly increase in diameter.

As they grow, bamboos store food and energy in roots and rhizomes. At the start of the growth cycle, the canes grow out of the ground rapidly to their maximum height. The leaves and canes produce food, which is stored in the rhizomes for the next growth cycle. Young bamboos are usually slow to establish, while older plants have more stored food and therefore grow more quickly.

Plant or divide bamboos in spring. Most enjoy full sun or partial shade. Bamboos tolerate a range of soil conditions as long as moisture is present, but they usually don’t like boggy or mucky soils. They are seldom bothered by pests. A carefully chosen bamboo is a beautiful addition to any garden. Low-growing types, such as pygmy bamboo (Pleioblastus spp.), are ideal as groundcovers or for erosion control. Small clumping bamboos, for example some of the species and cultivars of Fargesia, can serve as delicate accents; taller species, such as clumping Borinda boliana, make good screens or windbreaks. Some, like black bamboo (Phyllostachys nigra), make excellent specimens for large tubs, both indoors and outdoors. Because of its rapid growth, bamboo can act as a “carbon sink,” which makes it a good candidate for “green gardening.” To learn more about how bamboo can be part of your green gardening initiative, see page 11.

Five Beautiful Bamboos

Here’s a list of five excellent bamboos for home landscapes and their characteristics:

Bambusa multiplex ‘Alphonse Karr’ (hedge bamboo): Up to 20 feet tall; good for containers; clump-forming habit. Zones 8–10.

Borinda boliana: Up to 30 feet tall; heat-tolerant, noninvasive timber bamboo; clump-forming habit. Zones 7–10.

Fargesia dracocephala ‘Rufa’: 8 feet tall; vigorous, cold hardy, and wind tolerant; clump-forming habit. Zones 5–9.

Phyllostachys nigra (black bamboo): Up to 30 feet tall; jet black canes with green foliage and a running growth habit. Zones 7–10.

Pleioblastus viridistriatus (dwarf green-stripe bamboo): 3 to 4 feet tall; variegated foliage, running growth habit. Zones 5–10.

BAPTISIA

Baptisia, false indigo, wild indigo. Late-spring-blooming perennials.

Description: Baptisia australis, blue false indigo, bears 1-inch pealike purple-blue flowers in loose 1-foot spikes. The 3- to 4-foot, dense, bushy plants bear handsome 3-inch, cloverlike, gray-green leaves. Handsome black 2- to 3-inch seedpods dry well and rattle when ripe. Zones 3–9.

How to grow: Set out small plants or divisions in spring. These long-lived plants won’t need division for many years. Move self-sown seedlings when small. Grow in sunny, well-drained, average soil; allow plenty of room. Partial shade and rich soil promote weaker stems that need staking. Baptisias are drought tolerant and pest resistant.

Landscape uses: Feature single specimens in a border, or mass several baptisias as a foliage background for other plants. Allow plants to naturalize in a meadow.

BARBERRY

See Berberis

BASIL

Ocimum basilicum

Labiatae

Description: Sweet basil is a bushy annual, 1 to 2 feet high, with glossy opposite leaves and spikes of white flowers. Basil leaves are used in cooking, imparting their anise (licorice) flavor to dishes. Many cultivars are available with different nuances of taste, size, and appearance, including cultivars with cinnamon, clove, lemon, and lime overtones, as well as purple-leaved types such as ‘Dark Opal’ and ‘Rubin’. One of the most popular herbs in the garden, basil adds fine flavor to tomato dishes, salads, and pesto.

How to grow: Plant seed outdoors when frosts are over and the ground is warm, start indoors in individual pots, or buy bedding plants. If you start plants indoors, heating cables are helpful, since this is a tropical plant that doesn’t take kindly to cold. Plant in full sun, in well-drained soil enriched with compost, aged manure, or other organic materials. Space large-leaved cultivars, such as ‘Lettuce Leaf’, 1½ feet apart and small-leaved types such as ‘Spicy Globe’ 1 foot apart. Basil needs ample water. Mulch to retain moisture after the soil has warmed. Pinch plants frequently to encourage bushy growth, and pinch off flower heads regularly so plants put their energy into foliage production.

Grow a few basil plants in containers so you can bring them indoors before fall frost. Or make a second sowing outdoors in June in order to have small plants to pot up and bring indoors for winter. As frost nears, you can also cut off some end shoots of the plants in the garden and root them in water, to be potted later.

Basil can be subject to various fungal diseases, including Fusarium wilt, gray mold, and black spot, as well as damping-off in seedlings. Avoid these problems by waiting to plant outside until the soil has warmed and by not overcrowding plants. (If fungal disease strikes, refer to the Plant Diseases and Disorders entry for organic controls.) Japanese beetles may skeletonize plant leaves; control pests by hand picking.

Harvesting: Begin using the leaves as soon as the plant is large enough to spare some. Collect from the tops of the branches, cutting off several inches. Handle basil delicately so as not to bruise and blacken the leaves.

You can air-dry basil in small, loose bunches, but it keeps most flavorfully when frozen. To freeze basil, puree washed leaves in a blender or food processor, adding water as needed to make a thick but pourable puree. Pour the puree into ice-cube trays and freeze, then pop them out and store them in labeled freezer bags to use as needed in sauces, soups, and pesto. Pesto (a creamy mixture of pureed basil, garlic, grated cheese, and olive oil) will keep for a long time in the refrigerator with a layer of olive oil on top.

Uses: This widely used herb enhances the flavor of tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant. It is great in spaghetti sauce, pizza sauce, and ratatouille. It’s also excellent for fish or meat dishes, combining well with lemon thyme, parsley, chives, or garlic. Try it in stir-fries or in vegetable casserole dishes. Fresh basil leaves are delicious in salads. Try the lemon-and lime-scented cultivars in fresh fruit salads and compotes. Basil is also a staple ingredient in Thai and Vietnamese cuisine; cultivars such as ‘Siam Queen’ give the most authentic flavor to these dishes. Basil vinegars are good for salad dressings; those made with purple basils are colorful as well as tasty.

BATS

Most gardeners now know that bats are helpful allies in the war on garden pests. One bat can catch 1,000 bugs in a single night. If you put up a bat house and attract a colony to your yard, they’ll consume literally millions of pests with no further input from you. What a deal!

In the past, bats were the victims of a lot of bad press. They supposedly tangled in women’s hair, sucked blood, and spread rabies. The truth is that bats have no interest in human hair, male or female. North American bats eat bugs and sometimes fruit, but no blood. As for rabies, scientists once blamed bats for much of the spread of the disease, but have since decided that was an overreaction. Only about 1 percent of bats get the disease themselves, and far fewer pass it on to humans. In 30 years of recordkeeping, only 12 to 15 cases of human rabies have been traced to bats. Most of these incidents could have been avoided: The victim was not attacked by a swooping bat, but instead picked up a diseased bat flapping around on the ground. (A grounded bat is a sick bat.) To avoid a bite, don’t handle bats barehanded. If you must move them, use a shovel.

Of the nearly 1,000 bat species worldwide, 46 species are native to North America. The little brown bat, a common U.S. species, eats moths, caddis flies, midges, beetles, and mosquitoes. Other bats are important plant pollinators, including such Southwestern species as the long-nosed bat and Mexican long-tongued bat.

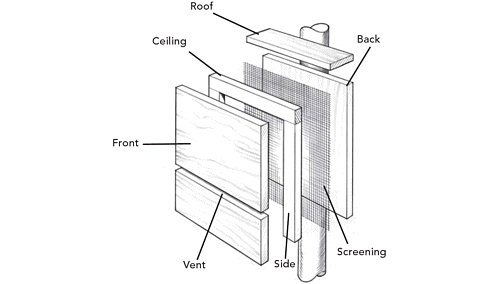

Bat house. From the outside, bat houses look like long, flat birdhouses without the round entrance holes. But instead of using a door in front, bats fly in through the bottom. They cling to the partitions inside to roost.

The best way to attract bats is to put up a bat house, a wooden box like a flattened birdhouse with an entrance slot in the bottom. You can buy bat houses from stores, catalogs, and Web sites that sell outdoor bird supplies.

If you’re handy, it’s also easy to make your own. Make the entrance slot of your homemade bat house ¾ inch wide. Scribe grooves in the inside back wall about 1⁄16 inch deep and ½ inch apart so the bats can hang on, or attach plastic mesh screening to the inside back wall. Fasten it 15 to 20 feet above the ground on the east or southeast side of a building or the trunk of a shade tree. Then be patient. If there are many roosts available in the neighborhood, bats may take several years to move into yours.

For more on bats and bat houses, check out Bat Conservation International’s Web site; see Resources on page 672.

BEAN

Phaseolus spp. and other genera

Fabaceae

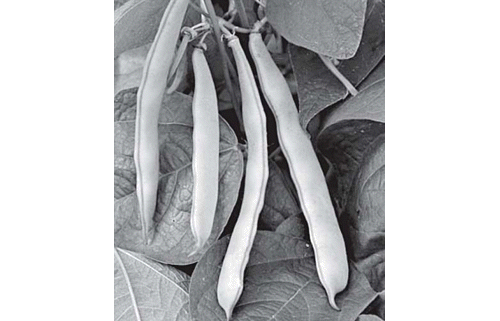

Dried or fresh, shelled or whole, beans are a favorite crop for home vegetable gardens. They are easy to grow, and the range of plant sizes means there is room for beans in just about any garden. Among the hundreds of varieties available, there are types that thrive in every section of the country.

Types: All beans belong to the legume family. Snap and lima beans belong to the genus Phaseolus, while mung, adzuki, garbanzo, fava, and others belong to different genera. In general, there are two main bean types: shell beans, grown for their protein-rich seeds, which are eaten both fresh and dried; and snap beans, cultivated mainly for their pods.

The two groups are further divided according to growth habit. Bush types are generally self-supporting. Pole beans have twining vines that require support from stakes, strings, wires, or trellises. Runner beans are similar to pole beans, although runners need cooler growing conditions. Half-runners, popular in the South, fall somewhere in between pole and bush beans.

Adzuki beans, which come from Japan, are extra rich in protein. The small plants produce long, thin pods that are eaten like snap beans. When mature at 90 days, they contain 7 to 10 small, nutty-tasting, maroon-colored beans that are tasty fresh or dried.

Black beans, also called black turtle beans, have jet black seeds and need approximately 3 months of warm, frost-free days to mature. The dried beans are popular for soups and stews. Most are sprawling, half-runner-type plants, but some cultivars, like ‘Midnight Black Turtle’, have more upright growth habits.

Black-eyed peas, also called cowpeas or southern peas, are cultivated like beans. They need long summers with temperatures averaging between 60° and 70°F. Use fresh pods like snap beans, shell and cook the pods and seeds together, or use them like other dried beans.

Fava beans, also known as broad, horse, or cattle beans, are one of the world’s oldest cultivated foods. They are second only to soybeans as a source of vegetable protein, but they’re much more common as a garden crop in Europe than in the United States. You won’t find a wide range of varieties in most seed catalogs, unless you choose a seed company that specializes in Italian vegetables. Unlike other beans, favas thrive in cold, damp weather. They take about 75 days to mature. Fava beans need to be cooked and shucked from their shells and the individual seed skins peeled off before eating.

Garbanzo beans, also called chickpeas, produce bushy plants that need 65 to 100 warm days. When dried, the nutty-tasting beans are good baked or cooked and chilled for use in salads.

Great Northern white beans are most popular dried and eaten in baked dishes. In short-season areas, you can harvest and eat them as fresh shell beans in only 65 days. Bush-type Great Northerns are extremely productive.

Horticultural beans are also known as shell, wren’s egg, bird’s egg, speckled cranberry, or October beans. Both pole and bush types produce a big harvest in a small space and mature in 65 to 70 days. Use the very young, colorful, mottled pods like snap beans, or dry the mature, nutty, red-speckled seeds.

Kidney beans require 100 days to mature but are very easy to grow. Use these red, hearty-tasting dried seeds in chili, soups, stews, and salads.

Lima beans, including types called butter beans or butter peas, are highly sensitive to cool weather; plant them well after the first frost. Bush types take 60 to 75 days to mature. Pole types require 90 to 130 days, but the vines grow quickly and up to 12 feet long. Limas are usually green, but there are also some speckled types. Use either fresh or dried in soups, stews, and casseroles.

Mung beans need 90 frost-free days to produce long, thin, hairy, and edible pods on bushy 3-foot plants. Eat the small, yellow seeds fresh, dried, or as bean sprouts.

Pinto beans need 90 to 100 days to mature. These large, strong plants take up a lot of space if not trained on poles or trellises. Use fresh like a snap bean, or dry the seeds.

Scarlet runner beans produce beautiful climbing vines with scarlet flowers. The beans mature in about 70 days. Cook the green, rough-looking pods when they are very young; use the black-and red-speckled seeds fresh or dried.

Snap beans are also known as green beans. While many growers still refer to snap beans as string beans, a stringless cultivar was developed in the 1890s, and few cultivars today have to be stripped of their strings before you eat them. Most cultivars mature in 45 to 60 days. This group also includes the flavorful haricots verts, also called filet beans, and the mild wax or yellow beans. For something unusual, try the yard-long asparagus bean. Its rampant vines can produce 3-foot-long pods, though they taste best when 12 to 15 inches long. Once the pods have passed their tender stage, you can shell them, too.

Soldier beans, whose vinelike plants need plenty of room to sprawl, are best suited to cool, dry climates. The white, oval-shaped beans mature in around 85 days. Try the dried seeds in baked dishes.

Garden cultivars of soybeans, also called edamame, are ready to harvest when the pods are plump and green. Boil the pods, then shell and eat the seeds. Or, you can let the pods mature and harvest as dry beans. Try ‘Early Hakucho’, ‘Butterbean’, and other varieties. The bush-type plants need a 3-month growing season but are tolerant of cool weather.

Planting: In general, beans are very sensitive to frost. (The exception is favas, which require a long, cool growing season; sow them at the same time you plant peas.) Most beans grow best in air temperatures of 70° to 80°F, and soil temperature should be at least 60°F. Soggy, cold soil will cause the seeds to rot. Beans need a sunny, well-drained area rich in organic matter. Lighten heavy soils with extra compost to help seedlings emerge.

Plan on roughly 10 to 15 bush bean plants or 3 to 5 hills of pole beans per person. A 100-foot row produces about 50 quarts of beans. Beans are self-pollinating, so you can grow cultivars side by side with little danger of cross-pollination. If you plan to save seed from your plants, though, separate cultivars by at least 50 feet.

Bean seeds usually show about 70 percent germination, and the seeds can remain viable for 3 years. Don’t soak or presprout seeds before sowing. If you plant in an area where beans haven’t grown before, help ensure that your bean crop will fix nitrogen in the soil by dusting the seeds with a bacterial inoculant powder for beans and peas (inoculants are available from garden centers and seed suppliers).

Plant your first crop of beans a week or two after the date of the last expected frost. Sow the seeds 1 inch deep in heavy soil and 1½ inches deep in light soil. Firm the earth over them to ensure soil contact.

Plant most bush cultivars 3 to 6 inches apart in rows 2 to 2½ feet apart. They produce the bulk of their crop over a 2-week period. For a continuous harvest, stagger plantings at 2-week intervals until about 2 months before the first killing frost is expected.

Bush beans usually don’t need any support unless planted in a windy area. In that case, prop them up with brushy twigs or a strong cord around stakes set at the row ends or in each corner of the bed.

Pole beans are even more sensitive to cold than bush beans. They also take longer to mature (10 to 11 weeks), but they produce about three times the yield of bush beans in the same garden space and keep on bearing until the first frost. In the North, plant pole beans at the beginning of the season—usually in May. If your area has longer seasons, you may be able to harvest two crops. To calculate if two crops are possible, note the number of days to maturity for a particular cultivar, and count back from fall frost date, adding a week or so to be on the safe side.

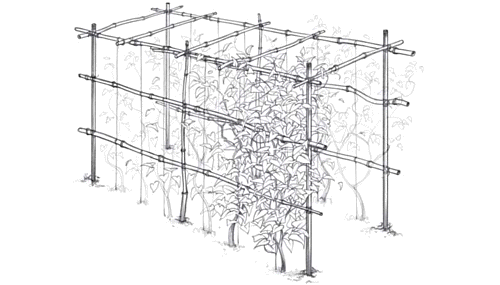

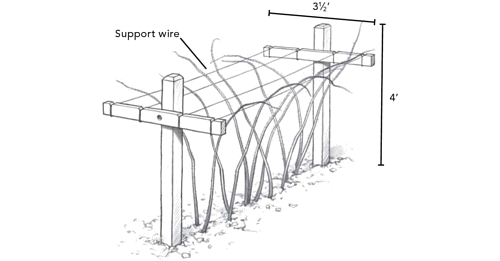

Plant pole beans in single rows 3 to 4 feet apart or double rows spaced 1 foot apart. Sow seeds 2 inches deep and 10 inches apart. Provide a trellis or other vertical support at planting or as soon as the first two leaves of the seedlings open. Planting pole beans around a tepee support is a fun project to try if you’re gardening with children, but it will be more difficult to harvest the beans than from a simple vertical trellis.

Bean trellis. Growing pole and runner beans on a trellis produces a clean, high-yielding crop in a small space. Use sturdy wooden or metal stakes for the uprights and bamboo poles for the crosspieces.

Growing guidelines: Bush beans germinate in about 7 days, pole beans in about 14. It’s important to maintain even soil moisture during this period and also when the plants are about to blossom. If the soil dries out at these times, your harvest may be drastically reduced. Water deeply at least once a week when there is no rain, being careful not to hose off any of the blossoms on bush beans when you water. Apply several inches of mulch (after the seedlings emerge) to conserve moisture, reduce weeds, and keep the soil cool during hot spells (high heat can cause blossoms to drop off).

Beans generally don’t need extra nitrogen for good growth because the beneficial bacteria that live in nodules on bean roots help to provide nitrogen for the plants. To speed up growth, give beans—particularly long-bearing pole beans or heavy-feeding limas—a midseason side-dressing of compost or kelp extract solution.

Problems: Soybeans, adzuki, and mung beans are fairly resistant to pests. Insect pests that attack other beans include aphids, cabbage loopers, corn earworms, European corn borers, Japanese beetles, and—the most destructive of all—Mexican bean beetles. You’ll find more information on these pests in the chart on page 458.

Leaf miners are tiny yellowish fly larvae that tunnel inside leaves and damage stems below the soil. To reduce leaf miner problems, pick off and destroy affected leaves.

Striped cucumber beetles are ¼-inch-long yellowish orange bugs with black heads and three black stripes down their backs. These pests can spread bacterial blight and cucumber mosaic. Apply a thick layer of mulch to discourage them from laying their orange eggs in the soil near the plants. Cover plants with row covers to prevent beetles from feeding; hand pick adults from plants that aren’t covered. Plant later in the season to help avoid infestations of this pest.

Spider mites are tiny red or yellow creatures that generally live on the undersides of leaves; their feeding causes yellow stippling on leaf surfaces. Discourage spider mites with garlic or soap sprays. Using a strong blast of water from the hose will wash mites off plants, but avoid this method at blossom time or you may knock the blossoms off.

To minimize disease problems, buy disease-free seeds and disease-resistant cultivars, rotate bean crops every one or two years, and space plants far enough apart to provide airflow. Don’t harvest or cultivate beans when the foliage is wet, or you may spread disease spores. Here are some common diseases to watch for:

Anthracnose causes black, egg-shaped, sunken cankers on pods, stems, and seeds and black marks on leaf veins.

Anthracnose causes black, egg-shaped, sunken cankers on pods, stems, and seeds and black marks on leaf veins.

Bacterial blight starts with large, brown blotches on the leaves; the foliage may fall off and the plant will die.

Bacterial blight starts with large, brown blotches on the leaves; the foliage may fall off and the plant will die.

Mosaic symptoms include yellow leaves and stunted growth. Control aphids and cucumber beetles, which spread the virus.

Mosaic symptoms include yellow leaves and stunted growth. Control aphids and cucumber beetles, which spread the virus.

Rust causes reddish brown spots on leaves, stems, and pods.

Rust causes reddish brown spots on leaves, stems, and pods.

Downy mildew causes fuzzy white patches on pods, especially of lima beans.

Downy mildew causes fuzzy white patches on pods, especially of lima beans.

If disease strikes, destroy infested plants immediately, don’t touch other plants with unwashed hands or clippers, and don’t sow beans in that area again for 3 to 5 years.

Harvesting: Pick green beans when they are pencil size, tender, and before the seeds inside form bumps on the pod. Harvest almost daily to encourage production; if you allow pods to ripen fully, the plants will stop producing and die. Pulling directly on the pods may uproot the plants. Instead, pinch off bush beans using your thumbnail and fingers; use scissors on pole and runner beans. Also cut off and discard any overly mature beans you missed in previous pickings. Serve, freeze, can, or pickle the beans the day you harvest them to preserve the fresh, delicious, homegrown flavor.

Pick shell beans for fresh eating when the pods are plump but still tender. The more you pick, the more the vines will produce. Consume or preserve them as soon as possible. Unshelled, both they and green beans will keep for up to a week in the refrigerator.

To dry beans, leave the pods on the plants until they are brown and the seeds rattle inside them. Seeds should be so hard you can barely dent them with your teeth. If the pods have yellowed and a rainy spell is forecast, cut the plants off near the ground and hang them upside down indoors to dry. Put the shelled beans in airtight, lidded containers. Add a packet of dried milk to absorb moisture, and store the beans in a cool, dry place. They will keep for 10 to 12 months.

BEE BALM

See Monarda

BEES

See Beneficial Insects

BEET

Beta vulgaris, Crassa group

Chenopodiaceae

Beets are a high-yield addition to any vegetable garden. They thrive in almost every climate and in all but the heaviest soils. You can bake, boil, steam, or pickle beets for use in soups, salads, and side dishes. Try growing a patch specifically for harvesting the delectable greens, which contain vitamins A and C and more iron and minerals than spinach.

Planting: Beets can grow in semishade but prefer full sun. They like deep, loose, well-drained, root-and rock-free soil. Like all root crops, beets benefit from hilled-up rows or beds. Dig in plenty of mature compost to lighten heavy soil.

Beets are most productive at temperatures of 60° to 65°F. Where summers are hot, plant them as a spring or fall crop, and as a winter crop in the Deep South. Sow this hardy vegetable directly in the garden a full month before the last expected frost or as soon as you can work the soil. When planting in summer or fall during hot and dry weather, soak seeds for 12 hours to promote germination.

Sow seeds ½ inch deep and 2 to 4 inches apart with 12 to 18 inches between rows. Except for a few monogerm (single-seeded) types, each beet seed is actually a small fruit containing up to eight true seeds. Thin the resulting clusters of seedlings to one per cluster. Transplant thinnings or enjoy the tiny, tender leaves in salads or as cooked greens. If you’re growing beets for greens only, then you don’t need to thin. Plant successive crops every 2 weeks until the weather begins to turn hot.

Growing guidelines: Early weeding is critical to success with any root crop, but beet roots bruise easily, so carefully hand-pull weeds that sprout near your young beet plants.

Once the roots reach 1 inch in diameter, harvest every other one, water well, and mulch to keep down weeds and conserve moisture. Be sure to provide about 1 inch of water a week. Otherwise, plants bolt (go to seed), and the roots will crack or become stringy and tough. Quick growth is the secret for tender roots, so water with compost tea or liquid seaweed extract every 2 weeks. See the Compost entry for instructions for making compost tea. Side-dress with compost at least once halfway through the growing period.

Problems: Beets that are thinned promptly and weeded and watered regularly are usually insect and disease free. The most common pests are leaf miners and flea beetles, but they seldom cause serious damage. Leaf miners are tiny black flies whose larvae tunnel within the beet leaves; control them by removing affected leaves. For more information on flea beetles, see page 459.

Boron deficiency can cause brown hearts, black spots in the roots, or lack of growth. If you’ve had problems with these symptoms, apply a foliar spray of liquid seaweed extract every two weeks and enrich your garden with compost and green manures to increase the supply of boron in the soil.

Harvesting: You can snip off up to a third of a plant’s greens without harming the roots. To harvest the roots, hand pull carefully to avoid bruising them. Beet roots are best when 1½ to 3 inches in diameter; they’ll start to deteriorate if you leave them in the ground for more than 10 days after they reach their full size. After pulling the roots, shake off the soil, and twist off—don’t cut off—the tops, leaving an inch or so of stems to prevent the roots from bleeding. To store beets for up to 6 months, layer undamaged roots between sand, peat, or sawdust in boxes; store in a cool place. You can also can or freeze beet roots or leaves.

BEGONIA

Begonia. Tender perennials grown as summer-and fall-blooming annuals or houseplants; one hardy perennial.

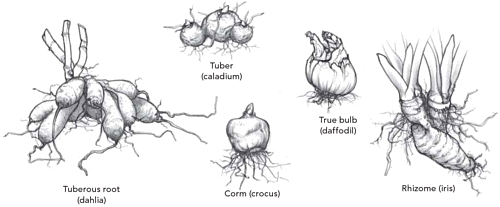

Description: The genus Begonia contains over 1500 species and hundreds of thousands of cultivars, grown for their beautiful flowers, as is the case with tuberous and wax begonias, or attractive leaves, as with rex and cane begonias. Begonias generally fall into one of four major groups—fibrous-rooted, tuberous-rooted, rhizomatous, and cane-stemmed—each with different habits and needs.

Begonia semperflorens-cultorum, wax begonia, is a tender perennial commonly grown as a reliable annual. Flowering begins when plants are small and continues until frost. Wax begonias bloom in shades of white, pink, and red, plus blended and edged combinations, on plants that can reach 15 inches or more by autumn. The male flowers normally have four petals (two rounded and two narrow) with showy yellow stamens in the center; the females have 2 to 5 smaller rounded petals around a tight, curly yellow knob. Female blooms occur in pairs, one on either side of each male flower. The shiny, thick, 1½- to 4-inch leaves may be green, reddish to bronze, or speckled with yellow, and appear “waxy,” giving these plants their common name. Perennial in Zone 10; elsewhere, grow as an annual or container plant and bring indoors when frost threatens.

Hardy Begonias

Most people think of begonias as bedding, hanging-basket, or indoor plants, but there is also a handsome perennial begonia that can take the cold. Winter hardy to Zone 6 (Zone 5 with protection), hardy begonia (Begonia grandis) bears large, open sprays of pink or white blooms from late summer into early fall on 1- to 2½-foot arching clumps of striking, angel-wing-type leaves. It thrives in partial shade (out of hot afternoon sun) and fertile, moist but well-drained soil with plenty of organic matter. Plant or divide in spring when it emerges, which is later than most plants. It looks stunning in a bed of ajuga or in woodland plantings with hostas and ferns.

Another popular type of begonia is the cane-stemmed group, including the angel-wing begonias. Representing several species (most prominently B. × argenteoguttata) and cultivars, these houseplants produce plain green or mottled leaves and clusters of brightly colored flowers. Upright cultivars can grow several feet tall; plants with drooping branches are ideal for hanging baskets.

The showy plants called hybrid tuberous begonias (B. tuberhybrida-cultorum) are commonly used in hanging baskets. Single or double male flowers can grow to 6 inches or more across, blooming in bright and pastel shades of white, pink, red, yellow, salmon, and combinations. The upright plants grow to about 2 feet tall. Perennial in Zone 10; in colder climates, bring indoors when frost threatens or treat as annuals.

Rex begonias (B. rex-cultorum) are the most widely grown rhizomatous begonias, the ultimate houseplant begonias. They produce green or reddish leaves, often attractively patterned with silver or black markings. Enjoy the many cultivars as indoor foliage plants.

How to grow: Buy plants or start wax begonias from seed, allowing 4 months from sowing to setting out transplants after the frost date. Take cuttings of particularly nice plants toward the end of summer to grow as houseplants through winter; root cuttings from them in early spring for planting out after frost. Set wax begonias out after the last frost in partial to dense shade; they’ll grow in full sun in the North if kept evenly moist. Plant in average, moist but well-drained soil; water during drought.

Start tuberous begonias indoors, planting them about 8 to 10 weeks before your frost-free date in a loose growing medium. Barely cover tubers with the concave side up (it should have little pink buds coming out of the center) and moisten lightly. Give lots of water and light after the shoots emerge. Move tubers to individual 4- or 5-inch pots when shoots are 1 to 3 inches tall. After all danger of frost is past, plant in partial shade in fertile, moist but well-drained soil with plenty of organic matter. Water liberally in warm weather; douse every 3 weeks or so with compost tea or fish emulsion. (See the Compost entry for instructions for making compost tea.) Stake plants to prevent them from falling under the weight of the flowers.

For container-grown tuberous begonias, choose larger pots (8 inches is a good size) and fill with a loose, rich potting mix. Care for them as you would plants in the ground. For hanging baskets, plant no more than three tubers in a 12-inch basket, and water frequently. To promote branching, pinch plants when they are about 6 inches tall.

When the leaves turn yellow and wither in fall, lift plants out of the ground with soil still attached. After a week or so, cut the stems to within a few inches of the tuber. Once the stem stub dries completely, shake the soil off the tubers and store in dry peat or sharp sand at 45° to 55°F. Leave pot-grown plants in their soil and bring indoors during winter, or store as you would those grown in the ground. Start them again next spring, replacing the soil for those in pots.

Angel-wing and rex begonias need plenty of bright but indirect light. Grow them indoors in a rich, well-drained potting mix. In summer, they appreciate some extra humidity, along with evenly moist soil and a dose of fish emulsion every 2 weeks. In winter, water more sparingly and do not feed.

Indoors, begonias are usually pest free. In the garden, slugs may be a problem; see the Slugs and Snails entry for details on controlling these pests. Stem rot will almost certainly occur on tuberous begonias in poorly drained soil; mildew will whiten the leaves in breezeless corners and pockets. Flower buds may drop in humid weather or if the soil is too dry.

Landscape uses: Outdoors, grow begonias anywhere you want some color in shady beds and borders, or use them in containers or hanging baskets, alone or with other decorative container plants, for portable color.

BELLFLOWER

See Campanula

BENEFICIAL ANIMALS

See Bats; Birds; Pests; Toads

BENEFICIAL INSECTS

Our insect allies far outnumber the insect pests in our yards and gardens. Bees, flies, and many moths help gardeners by pollinating flowers; predatory insects eat pest insects; parasitic insects lay their eggs inside pests, and the larvae that hatch then weaken or kill the pests; dung beetles, flies, and others break down decaying material, which helps build good soil.

Bees and Wasps

Honeybees are called the “spark plugs” of agriculture because of their importance in pollinating crops, but other wild bees and wasps are also important pollinators and natural pest-control agents.

Bees: All bees gather and feed on nectar and pollen, which distinguishes them from wasps and hornets. As they forage for food, bees transfer stray grains of pollen from flower to flower and pollinate the blooms. There are some 20,000 species of bees worldwide. Of the nearly 5,000 in North America, several hundred are vital as pollinators of cultivated crops. Many others are crucial to wild plants.

Pesticide use, loss of habitat, and pest problems such as mites have vastly reduced wild and domestic bee populations. Most recently, a phenomenon called Colony Collapse Disorder is decimating populations of honeybees in the United States. It’s not known for sure what is causing this problem, in which worker bees suddenly die out, leaving behind the queen bee, the nurse bees, and the unborn brood (which in turn die without the support of the worker bees). Possibilities include diseases or parasites, or damaging effects of chemical pesticides on bees’ nervous systems or immune systems.

The good news is that native bees ranging from bumblebees to tiny “sweat bees” are still hard at work pollinating crops and gardens. The best way to encourage native bees is to tend a flower garden with as long a bloom season as possible. Leave some bare ground available for the bees to tunnel in to make nests, and provide a shallow water source where they can drink.

Parasitic wasps: Most species belong to one of three main families: chalcids, braconids, and ichneumonids. They range from pencil-point-size Trichogramma wasps to huge black ichneumonid wasps. Parasitic wasps inject their eggs inside host insects; the larvae grow by absorbing nourishment through their skins.

Yellow jackets: Most people fear yellow jackets and hornets, but these insects are excellent pest predators. They dive into foliage and carry off flies, caterpillars, and other larvae to feed to their brood. So don’t destroy the gray paper nests of these insects unless they are in a place frequented by people or pets, or if a family member is allergic to insect stings.

Beetles

While some beetles, such as Japanese beetles and Colorado potato beetles, can be serious home garden pests, others are some of the best pest-fighters around.

Lady beetles: This family of small to medium, shiny, hard, hemispherical beetles includes more than 3,000 species that feed on small, soft pests such as aphids, mealybugs, and spider mites. (Not all species are beneficial—for example, Mexican bean beetles also are lady beetles.) Both adults and larvae eat pests. Most larvae have tapering bodies with several short, branching spines on each segment; they resemble miniature alligators. Convergent lady beetles (Hippodamia convergens) are collected from their mass overwintering sites and sold to gardeners, but they usually fly away after release unless confined in a greenhouse.

Ground beetles: These swift-footed, medium to large, blue-black beetles hide under stones or boards during the day. By night they prey on cabbage root maggots, cutworms, snail and slug eggs, and other pests; some climb trees to capture armyworms or tent caterpillars. Large ground beetle populations build up in orchards with undisturbed groundcovers and in gardens under stone pathways or in semipermanent mulched beds.

Rove beetles: These small to medium, elongated insects with short, stubby top wings look like earwigs without pincers. Many species are decomposers of manure and plant material; others are important predators of pests such as root maggots that spend part of their life cycle in the soil.

Other beetles: Other beneficial beetles include hister beetles, tiger beetles, and fireflies (really beetles). Both larvae and adults of these beetles eat insect larvae, slugs, and snails.

Flies

We usually call flies pests, but there are beneficial flies that are pollinators or insect predators or parasites.

Tachinid flies: These large, bristly, dark gray flies place their eggs or larvae on cutworms, caterpillars, corn borers, stinkbugs, and other pests. Tachinid flies are important natural suppressors of tent caterpillar or armyworm outbreaks.

Syrphid flies: These black-and-yellow or black-and-white striped flies (also called flower or hover flies) are often mistaken for bees or yellow jackets. They lay their eggs in aphid colonies; the larvae feed on the aphids. Don’t mistake the larvae—unattractive gray or transluscent sluglike maggots—for small slugs.

Aphid midges: Aphid midge larvae are tiny orange maggots that are voracious aphid predators. The aphid midge is available from commercial insectaries and can be very effective if released in a home greenhouse.

Other Beneficials

Dragonflies: Often called “darning needles,” dragonflies and their smaller cousins, damselflies, scoop up mosquitoes, gnats, and midges, cramming their mouths with prey as they dart in zig-zag patterns around marshes and ponds.

Lacewings: The brown or green, alligator-like larvae of several species of native lacewings prey upon a variety of small insects, including aphids, scale insects, small caterpillars, and thrips. Adult lacewings are delicate, ½- to 1-inch green or brown insects with large, transparent wings marked with a characteristic fine network of veins. They lay pale green oval eggs, each at the tip of a long, fine stalk, along the midrib of lettuce leaves or other garden plants.

True bugs: True bug is the scientifically correct common name for a group of insects. This group does include several pest species, but there are also many predatory bugs that attack soft-bodied insects such as aphids, beetle larvae, small caterpillars, pear psylla, and thrips. Assassin bugs, ambush bugs, damsel bugs, minute pirate bugs, and spined solider bugs are valuable wild predators in farm systems.

Spiders and mites: Although mites and spiders are arachnids, not insects, they are often grouped with insects because all belong to the larger classification of arthropods. Predatory mites are extremely small. The native species found in trees, shrubs, and surface litter are invaluable predators. Phytoseiid mites control many kinds of plant-feeding mites, such as spider mites, rust mites, and cyclamen mites. Some also prey on thrips and other small pests. Many types of soil-dwelling mites eat nematodes, insect eggs, fungus gnat larvae, or decaying organic matter.

It’s unfortunate that so many people are scared of spiders, because they are some of the best pest predators around. We are most familiar with spiders that spin webs, but there are many other kinds. Some spin thick silk funnels; some hide in burrows and snatch insects that wander too close, while others leap on their prey using a silk thread as a dragline.

Encouraging Beneficials

The best way to protect beneficial insects is to avoid using toxic sprays or dusts in the garden. Even organically acceptable sprays such as insecticidal soap and neem can kill beneficial species, so use them only when absolutely necessary to preserve a crop and then only on the plants being attacked. Be careful when you hand pick or spray pest insects, or you may end up killing beneficial insects by mistake. While many beneficials are too small to be seen with the unaided eye, it’s easy to learn to identify the larger common beneficials such as lacewings, tachinid flies, and lady beetles.

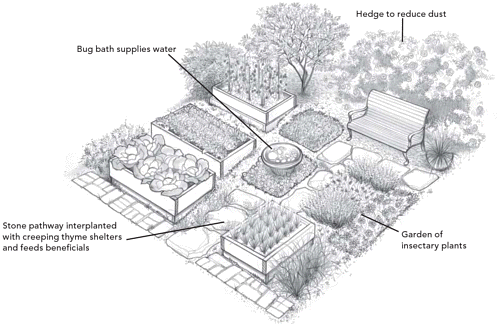

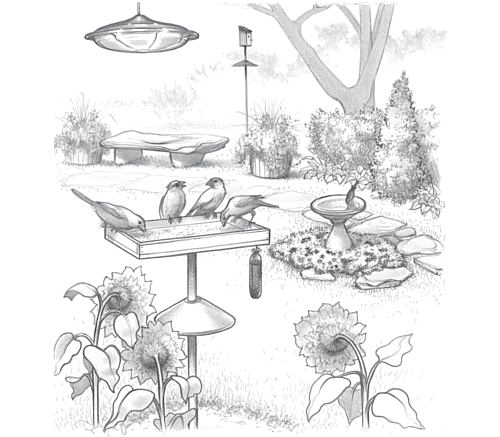

You can make your yard and garden a haven for beneficials by taking simple steps to provide them with food, water, and shelter, as shown in the illustration at right.

Food sources. A flower bed or border of companion plants rich in pollen and nectar, such as catnip, dill, and yarrow, is a food source for the adult stages of many beneficials, including native bees, lacewings, and parasitic wasps. To learn more about planting a garden for pollinators and other beneficial insects, see page 6.

Water. Many types of beneficial insects are too small to be able to drink water safely from a stream, water garden, or even a regular birdbath. To provide a safe water supply for these delicate insects, fill a shallow birdbath or large bowl with stones. Then add just enough water to create shallow stretches of water with plenty of exposed landing sites where the insects can alight and drink without drowning. You’ll need to check this bug bath daily, as the water may evaporate quickly on sunny days.

Shelter. Leave some weeds here and there among your vegetable plants to provide alternate food sources and shelter for beneficial species. Plant a hedge or build a windbreak fence to reduce dust, because beneficial insects dehydrate easily in dusty conditions. And set up some permanent pathways and mulched areas around your yard and garden. These protected areas offer safe places for beneficials to hide during the daytime (for species that are active at night), during bad weather, or when you’re actively cultivating the soil.

Attracting beneficial insects. Making your garden a haven for beneficial insects is easy and fun. It’s also one of the cheapest and most environmentally sound ways to help prevent insect pests from getting the upper hand on your food crops and ornamentals.

To learn more about encouraging beneficial insects in your yard, visit the Web sites of organizations such as the Xerces Society; see Resources on page 672.

Buying Beneficial Insects

Many garden supply and specialty companies offer beneficial insects for sale to farmers, nursery owners, and gardeners. You can buy everything from aphid midges to lady beetles and lacewings to predatory mites.

Buying and releasing beneficial insects on a large scale, such as a commercial farm field, or in a confined place, such as a greenhouse, can be a very effective pest-control tactic. However, in a typical home garden it’s rarely worthwhile. Chances are that most of the insects you release will disperse well beyond the boundaries of your yard. While that may be helpful for your neighborhood in general, it won’t produce any noticeable improvement in the specific pest problem that you hoped the good bugs would control in your garden. Overall, it’s more effective to invest money in plants that attract beneficial insects to your yard than it is to buy and release beneficial insects.

If you decide to experiment with ordering beneficial insects, make sure you identify the target pest, because most predators or parasites only attack a particular species or group of pests. Find out as much as you can by reading or talking to suppliers before buying beneficials.

Get a good look at the beneficials before releasing them so that you’ll be able to recognize them in the garden. You don’t want to mistakenly kill them later on, thinking them to be pests. A magnifying glass is useful for seeing tiny parasitic wasps and predatory mites. Release some of the insects directly on or near the infested plants; distribute the remainder as evenly as possible throughout the rest of the surrounding area.

BERBERIS

Barberry. Thorny evergreen or deciduous shrubs.

Description: Berberis julianae, wintergreen barberry, grows from 3 to 6 feet and has shiny, evergreen, oblong leaves that may turn rich red during a cold winter. Zones 6–8.

B. thunbergii, Japanese barberry, is a popular, but invasive, deciduous shrub that is best avoided because seedlings (sown by songbirds) crowd out native plants in wild areas. Zones 4–8.

Both barberry species produce small yellow flowers in spring and berries in summer and fall.

How to grow: Barberries need full sun and tolerate a wide range of soil conditions. In the North, plant wintergreen barberry in a spot protected from winter winds; in the South, site it out of summer wind and plant in fall or winter.

Landscape uses: Use wintergreen barberry in hedges, shrub borders, or as foundation shrubs.

BETULA

Birch. Single-or multiple-trunked deciduous trees.

Description: Birches offer year-round landscape interest with their peeling bark, graceful branches, and magnificent fall color.

Betula lenta, sweet birch, is a handsome native with red-brown, cherrylike bark and a pyramidal habit in youth. Like the other birches, it bears drooping flower spikes called catkins in spring; these are interesting but not showy. The leaves stay freshly green and unmarred through summer, turning yellow in fall. Crushed or scratched twigs yield a rich, root beer aroma. Where it grows wild, sweet birch has been a source of the oil for making homemade root beer. Zones 4–6.

B. nigra, river birch, is a native tree found growing along river banks and rich bottomlands in much of the eastern United States. Pyramidal in youth, this multi-trunked tree reaches heights of 30 to 40 feet in the landscape; the occasional old-timer approaches 100 feet. River birch features shredding, papery bark in shades of cream and pale salmon, and clear yellow autumn leaf color in most years. ‘Heritage’ is a nearly-white-barked cultivar that can replace the popular but insect-prone B. papyrifera in the landscape. Zones 4–8.

B. papyrifera, paper or canoe birch, is a native of the Northern evergreen forests and performs best in cooler climates. Known for its white bark with dramatic black markings, this tree develops a rounded outline with age. Most paper birches hold their lower branches; be sure to allow space for the tree’s mature spread in your landscape plans. The yellow fall color combines well with its bark and with the reds and oranges of other trees. Plan on a mature height of 50 to 70 feet. Zones 4–8.

B. pendula, European white birch, is similar in many ways to paper birch. Its branches have a drooping habit, and its bark splits into black fissures toward the base. Zones 3–6.

B. populifolia, gray birch, is a workhorse among birches. Thriving in almost any soil, this handsome tree has grayish white bark with black markings and a multi-trunked habit. A good birch for minimal-maintenance situations. Zones 4–6.

How to grow: Most birches require light shade. Give them evenly moist, humus-rich soil, a shaded root zone, and plenty of mulch. River birch tolerates some standing water. Planted out of their element, birches soon begin to decline and, if they haven’t already, attract insects such as the bronze birch borer and the birch leaf miner. Stressed trees most often feature the D-shaped holes left in the bark by borers and the brown paperlike leaves caused by leaf miners; reduce both problems by selecting an appropriate planting site. Gray and river birches, especially ‘Heritage’, show resistance to these devastating insects.

Landscape uses: Sweet or paper birch are good choices for naturalizing in the shade of taller trees. Use gray or river birch in clumps or masses.

BIENNIALS

Botanically speaking, biennials are plants that complete their life cycle in two years, germinating the first year then flowering and dying the second. During the first growing season, true biennials germinate and produce a mound of foliage, called a rosette, which is a circular cluster of leaves usually borne at or just above the ground. They winter over in rosette form. In the second season, they send up a flower stalk. After blooming, biennials produce seeds and die at the end of the season.

True biennials, such as Canterbury bells (Campanula medium), standing cypress (Ipomopsis rubra), giant sea holly (Eryngium giganteum), and sweet William (Dianthus barbatus), are winter hardy in most regions and usually have fleshy taproots. While some may hold on and bloom for a third or even a fourth season, they produce the best bloom during the second season from seed.

Plants don’t always follow our clear-cut definitions, though, and in reality, gardeners grow some plants as biennials whether they’re true biennials or not. These include short-lived perennials that are able to winter over with some protection—such as pansies and English daisies (Bellis perennis). These plants bloom best when planted in late summer or fall, mulched or otherwise protected over winter, then pulled up and replaced after they bloom the following spring or summer. (Check with your local Cooperative Extension office or local gardeners to determine how to grow biennials in your area, since the best schedule varies depending on your climate and hardiness zone.)

To make matters more confusing, some biennials can be grown as annuals. For example, if sown indoors in midwinter, ‘Foxy’ hybrid foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) will bloom its first year from seed.

Many true biennials, along with plants grown as biennials, readily self-sow their seed. Giant sea holly, honesty (Lunaria annua), foxglove (Digitalis purpurea), forget-me-nots (Myosotis sylvatica), and hollyhocks (Alcea rosea), all are reliable self-sowers. Thus, if you plant seed of these biennials two years in a row, you’ll have plants in bloom every year from then on—providing the same effect in the garden as perennials do. Just remember to allow some flowers to mature each year and set seed for next year’s plants.

In the following discussion, the term biennial is used to refer to any plants grown as biennials, not just to true biennials.

Biennials in the Landscape

Biennials are attractive in flower beds and borders throughout the landscape, and large-size plants such as hollyhocks (A. rosea) can even be used as specimen plants or for adding color to a shrub border. For best results, interplant them with annuals the first year while the rosettes of foliage are still small. The second season, add more annuals around the plants to fill the spaces the biennials will leave in the garden after they have finished blooming.

Keep in mind that if you buy plants the first year, you will have bloom the first season. If you are starting your own seeds, plan ahead, since it will take two seasons to get the floral display you want. The flowers of most biennials last several weeks before fading. Some, including honesty and mullein (Verbascum spp.), have attractive seed heads that you can use in dried arrangements.

Buying and Starting Plants

Popular biennials like pansies and hollyhocks are sold by nurseries along with annual bedding plants in spring. They have been grown for the first season by the nursery and are offered at a stage where they will bloom in the current season. Plant and maintain them as you would annuals.

Purchase only healthy, bright green, well-rooted plants. Avoid overgrown, leggy, or wilted plants—their performance will be disappointing. Some biennials, including pansies and foxglove, are offered for fall planting. Plant them in early fall to allow ample time for the roots to get established. Mulch the rosettes after hard frost. This protects the crown and prevents repeated freezing and thawing of the soil that can cause roots to heave out of the ground.

Many choice biennials are not offered by nurseries as plants. If you want them, you’ll have to grow them from seed. You’ll find a wide range of biennials offered by mail-order nurseries on the Internet.

Biennials often do not transplant well (many have taproots), so to grow them from seed, sow seeds indoors in individual pots, peat pots, or cell packs. Use a sterile commercial soil mix or a compost-based potting mix. Start seeds of true biennials in early summer so seedlings will be ready to plant out in fall. Sow seeds of pansies, English daisies, and other perennials treated as biennials in August. Protect the young plants with mulch or keep them in a cold frame until early spring.

You can also direct-seed biennials into well-prepared outdoor beds. Keep the seedbed evenly moist but not wet. Take care to protect the seeds from disturbance until they germinate and become well established. Sow seed thickly, then use small scissors to clip off unwanted seedlings. When seedlings are established, mulch the beds to conserve water.

Biennials for Sun and Shade

As these lists show, there are more biennials than you think—including such beloved favorites as hollyhocks, Canterbury bells, sweet Williams, forget-me-nots, evening primroses, and foxgloves. Some are best suited for sun, some prefer shade, and a few thrive in both conditions. Perennials grown as biennials are also included here.

Biennials for Sunny Sites

Alcea rosea (hollyhock)

Campanula medium (Canterbury bells)

Campanula spicata (bellflower)

Cynoglossum amabile (Chinese forget-me-not)

Dianthus armeria (Deptford pink)

Dianthus barbatus (sweet William)

Eryngium giganteum (giant sea holly)

Glaucium flavum (horned poppy)

Ipomopsis rubra (standing cypress)

Lavatera arborea (tree mallow)

Lunaria annua (money plant)

Malva sylvestris (high mallow)

Matthiola incana (stock)

Myosotis spp. (forget-me-nots)

Oenothera spp. (evening primroses)

Onopordum acanthium (cotton thistle)

Silene armeria (sweet William catchfly)

Verbascum spp. (mulleins)

Biennials for Shady Sites

Campanula medium (Canterbury bells)

Digitalis purpurea (foxglove)

Lunaria annua (money plant)

Myosotis spp. (forget-me-nots)

Phacelia bipinnatifida (phacelia)

Planting and Maintenance

Most biennials prefer a loamy soil with ample organic matter and a pH between 6.0 and 7.5. If you’re already growing a wide variety of flowers, you’ll probably have no trouble with most biennials. For best results, plant biennials in a bed with soil that has been turned to at least a shovel’s depth. Thoroughly incorporate organic matter such as compost, along with any necessary soil amendments and fertilizers. (Have your soil tested if you are unsure about its fertility.)

Set purchased plants with their crowns at or just below the soil surface. If you’re transplanting biennials from peat pots, remove all or a portion of the pots. Handle biennial transplants carefully, since many have taproots. Take care not to damage the taproot when planting.

Keep plants well watered until they’re established. An inch of water per week is adequate for plants that are growing in well-prepared soil. Most are fine without supplemental fertilizer: Compost or other organic matter added to the soil at planting time should suffice. Weed the beds regularly so that your biennials won’t have to compete for light, water, and nutrients. Once plants are established, mulch them to conserve soil moisture and control weeds.

Pinching the plants may help control the height and spread of some biennials, but it is generally unnecessary. Removing spent flowers prolongs the blooming season. You may have to stake certain tall plants such as standing cypress, stocks, and mallows, especially in areas with high winds.

As a rule, biennials are fairly pest free. Good cultural practices are the best prevention for both insects and diseases. If serious problems do flare up, spray with an appropriate organic control. Plants with viral diseases should be destroyed. For more on pest and disease control, see the Pests and Plant Diseases and Disorders entries.

BIOLOGICAL CONTROL

See Beneficial Insects; Pests

BIRCH

See Betula

BIRDS

Birds are most gardeners’ favorite visitors, with their cheerful songs, sprightly manners, and colorful plumage. But birds are also among nature’s most efficient insect predators, making them valuable garden allies. In an afternoon, one diminutive house wren can snatch up more than 500 insect eggs, beetles, and grubs. Given a nest of tent caterpillars, a Baltimore oriole will wolf down as many as 17 of the pests per minute. More than 60 percent of the chickadee’s winter diet is aphid eggs. And the swallow lives up to its name by consuming massive quantities of flying insects—by one count, more than 1,000 leafhoppers in 12 hours.

Unless your property is completely bare, at least some birds will visit with no special encouragement from you. Far more birds, however, will come to your yard and garden if you take steps to provide their four basic requirements: food, water, cover, and a safe place in which to raise a family. Robins, nuthatches, hummingbirds, titmice, bluebirds, mockingbirds, cardinals, and various sparrows are among the most common garden visitors.

Food and Feeding

Food is the easiest of the four basic requirements to supply. If your landscape is mostly lawn and hard surfaces, you can use feeders as the main food supply while you add plantings of seed-producing annuals and perennials, grasses, fruiting trees, and shrubs. And if your yard is already a good natural habitat, where plants are the primary food source (as they should be), feeders can still provide extra nourishment during winter, early spring, drought, and at other times when the natural food supply is low. Also, carefully placed feeders allow you and your family to watch and photograph birds.

Some birds, including juncos, mourning doves, and towhees, feed on the ground, while others, including finches, grosbeaks, nuthatches, titmice, and chickadees, eat their meals higher up. In order to attract as many different birds as possible, use a variety of feeders—tube feeders for sunflower seed and Nyjer (also called niger or thistle seed), platform feeders, hopper feeders, shelf and hanging types, and (in cool weather) suet cakes in special suet cage feeders. No matter what the style, the feeder should resist rain and snow, and it should be easy to fill and clean. It should hold enough birdseed that you don’t have to refill it every day, but not so much that the food spoils before it can all be eaten.

Place feeders at varying heights, near the protective cover of a tree or shrub if possible. You can spread them around the yard or group them in one or more “feeding stations” where they’re easy to see from the kitchen, deck, or wherever you and your family enjoy birdwatching. Remember to site them where they’re easy to get to—a feeder at a far end of the yard means a long trek out to fill it, and you’ll be less likely to keep up with it, especially in bad weather, when birds need it most.

Creating a bird garden. Diversity is the key to attracting birds to your yard. Include various types of seed and feeders; a rich array of plants, birdhouses, and nest sites; and make sure water is available year-round.

Best birdseed: You can attract virtually all common seed-eating birds with just two kinds of birdseed: black oil sunflower seed (the smallest of the sunflower types and a favorite of many birds) and white proso millet (the food of choice among ground-feeding species). Some birds have special favorites: goldfinches, pine siskins, and purple finches love Nyjer; tufted titmice and chickadees enjoy peanut kernels. Woodpeckers, chickadees, titmice, and nuthatches love suet blocks. To attract the greatest possible diversity of birds, use black sunflower seed in your tube feeders, and a mix that includes black sunflower and millet in tray, platform, hopper, and ground feeders. Round out the menu with such nourishing but more species-specific seeds as red proso millet, black-and gray-striped sunflower seeds, peanut kernels, Nyjer (in special tube feeders with tiny openings), and milo and cracked corn for ground feeders.

High-quality birdseed and seed mixes are available from wild bird specialty stores and mail-order and catalog wild bird specialty suppliers. Locally, check out pet stores, nature centers, farm stores, garden stores, and hardware stores.

Bird-Attracting Basics

Here’s an overview of some surefire ways to bring more birds to your yard.

- Offer a variety of seed in different styles of feeders placed at varying levels to cater to the needs of different species.

- When adding plants, use as many different food-bearing trees and shrubs as possible.

- Mix short trees and shrubs with tall trees, and include some evergreens like junipers (Eastern red cedar) for food and shelter.

- Combine open spaces with dense plantings.

- Grow grasses, vines, and flowers for seeds and nectar.

- Put birdbaths in the open, so birds will have a clear view when drinking, but near cover, to provide a fast escape.

- Buy a heated birdbath or add a heating coil in winter to keep the water surface open for thirsty birds.

Suet: In cold weather, beef suet can help birds maintain their body heat. Woodpeckers especially appreciate suet. You can buy suet cakes that are shaped to fit suet cages, are tidy and convenient to use, and are rendered so they hold up better if the weather warms. Or you can buy raw suet from the butcher at your grocery store (it’s usually available at the meat counter in winter). Hang the fat in a plastic mesh bag (such as an onion bag) or wire holder (to keep large birds from stealing the entire chunk), or dip pine cones in melted suet and hang the cones from branches.

Special feeding: Birdfeeders will attract the most customers in winter and early spring, when natural food supplies are low. But summer feeding is also rewarding. Fruits such as oranges, apples, and bananas attract many species, including orioles, robins, tanagers, and mockingbirds. Simply cut the fruit in half and stick it on tree branches, or on one of the special fruit feeders available from wild bird suppliers.

Use your vegetable garden as a source of food for birds. Grow a few rows of sunflowers, wheat, sorghum, and millet just for them. In fall, let late-maturing vegetables and flowers (coneflowers are special favorites) go to seed. And don’t till under cover crops such as buckwheat and rye until spring.

Hummingbirds: Hummingbirds are popular summer visitors in almost all parts of the country, and year-round residents in parts of the Southwest and California. You can easily attract them to your garden with feeders that dispense a sugar-water (“nectar”) solution. Sugar water, however, provides only a quick energy boost and no real sustenance, so it’s best to hang hummingbird feeders near natural nectar sources, such as columbines and honeysuckles. You can buy sugar-water nectar for hummingbird feeders, or make your own by mixing ¼ cup sugar in 2 cups water. Boil the water first, then add the sugar and let the solution cool before pouring it into the feeder.

To keep mold from developing, clean the feeders every 3 to 4 days in very hot water (you can add white vinegar in a 1-to-10 ratio of vinegar to water to disinfect them, then rinse well in hot water), using a bottle brush to clean the feeding ports. Because you’ll be cleaning the feeders often, choose disk-shaped feeders with flat feeding ports; they’re the easiest style to clean. When the feeders are dry, refill them with fresh sugar solution. Don’t use honey or brown sugar to make the nectar—it can foster a fungal growth on the hummingbirds’ beaks. And rather than adding red food coloring to the solution, choose a feeder with red feeding ports to attract the hummers.

Squelching squirrels and bigger birds: Hungry squirrels and chipmunks can be a problem at feeders. They can get into even hard-to-reach feeders and, once there, quickly empty them. Keep them away from pole-mounted stations by attaching a metal collar on the pole just beneath the feeder. You can also buy domed plastic squirrel guards from stores, catalogs, and Web sites that sell wild bird supplies, and attach them over or underneath either hanging or pole-mounted feeders.

But the best defense against aggressive squirrels is to buy a birdfeeder with perches that respond to a squirrel’s weight. A good choice is a metal hopper feeder with perches that drop down under a squirrel’s weight, causing a metal barrier to close tightly over the feeding ports. These heavy-duty feeders are nearly indestructible and usually do the trick. Other options are the popular battery-operated hanging feeders that send squirrels flying when they land on a perch.

If large or aggressive birds like grackles and pigeons dominate your feeders and frighten away small birds, distract them with other snacks. Toss some cracked corn and milo or stale bread on the ground several yards from the stations to draw the bigger birds away. (But clean it up nightly so you don’t also attract rats or other unwelcome hungry visitors.) Another effective solution is to simply add more feeders to reduce the competition. Large birds tend to avoid tube feeders, preferring tray and platform feeders. By providing both types, you’ll make sure the smaller birds get their share.

Water All Year

Providing water is likely to attract an even wider range of birds than putting out birdfeeders will. A clean, accessible, reliable water source can help birds survive in winter when natural water sources are frozen, and it’s also helpful during droughts or in arid regions such as the Southwest.

Set a birdbath in the open and at least 3 feet off the ground. Choose a spot near shrubs or overhanging branches to provide an escape route from cats, hawks, and other predators. The water in the bath should be no deeper than 2 inches. Putting a few rocks or pebbles in the birdbath will help birds get their footing. Birds (including hummingbirds) are particularly attracted to the sound of moving water, and many birdbaths now come with a drip hose attachment or built-in recirculating fountain feature. (Some of the fountains are even solar-powered.) You can also buy a separate drip hose attachment for your current birdbath, or simply hang a leaky can or jug, filled with water daily, from a branch over the bath.

In winter, birds need shallow, open water. Commercial immersion water heaters will keep the water in birdbaths thawed in winter, or buy one of the many birdbath models with a heating element built in. They are available from stores, Web sites, and catalogs that sell wild bird supplies. You can try to keep water from freezing by pouring warm water into the baths as needed, but on very cold days, the water can refreeze in less than an hour, so a heating element or heated birdbath is a better option.

Cover and Nest Sites

Cover is any form of shelter from enemies and the elements. Different bird species favor different kinds of cover. Mourning doves, for example, prefer evergreen groves, while many songbirds prefer the refuge of densely twiggy shrubs. Likewise, most species require a particular kind of nest site in which to raise a family. Some birds, including red-winged blackbirds, nest in high grass; others, such as cardinals, nest in dense foliage; and still others, such as woodpeckers, owls, and bluebirds, are cavity nesters, raising their young in nests built in holes in tree trunks.

You can add more nest sites and attract many types of birds to your yard with birdhouses. Different species have different housing requirements, but there are ready-made birdhouses and build-your-own plans for everything from bluebirds to barn owls. Whichever birdhouse you choose, make sure that it is weather-resistant, that its roof is pitched to shed rain, and that there are holes in the bottom for drainage and in the walls or back for ventilation. A hinged or removable top or front makes cleaning easier. Position birdhouses with their entrance holes facing away from prevailing winds, and clean out the boxes after every nesting season.

Landscaping for Birds

Feeders, birdbaths, and birdhouses play important roles in attracting birds. But trees, shrubs, and other vegetation can do the whole job naturally. Plants provide food, cover, and nest sites, and because they trap dew and rain and control runoff, they help provide water, too.

When adding plants to your landscape, choose as many food-bearing species as possible, with enough variety to assure birds a steady diet of fruit, buds, and seeds throughout the year. Mix plantings of deciduous and evergreen species in order to maintain leafy cover in all seasons. Species that are native to your region are generally best, because the local birds evolved with them and will turn to them first for food and cover. Combine as many types of vegetation as possible: tall trees, shorter trees, shrubs, grasses, flowers, and groundcovers. The greater the plant diversity, the greater the variety of birds you will attract. See “Trees and Shrubs for Birds” for some top choices.

Hummingbirds have their own landscape favorites. Preferred trees and shrubs include tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera), mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), cotoneasters (Cotoneaster spp.), flowering quinces (Chaenomeles spp.), and rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus). A trumpet vine (Campsis radicans) is a gorgeous sight in bloom, with its large, showy orange-red flowers, and it is a hummingbird favorite, as are honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.), annual climbing nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus), and morning glory (Ipomoea tricolor). Favored perennials include columbines (Aquilegia spp.), common foxglove (Digitalis purpurea), fuchsias (Fuchsia spp.), cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), penstemons (Penstemon spp.), torch lilies (Kniphofia spp.), sages (Salvia spp.), delphiniums (Delphinium spp.), and bee balm (Monarda didyma).

Trees and Shrubs for Birds

To attract birds to your landscape, look at plants from a bird’s point of view. Do they provide food and shelter? Nest sites? Try to plant a variety to provide birds with protective cover and a varied diet throughout the year. The following trees and shrubs are excellent food sources—producing berries, nuts, or seeds that birds will flock to. Evergreen species provide food but are also especially important for winter cover. These species will grow in most regions of the country.

Deciduous Shrubs

Cornus sericea (red-osier dogwood)

Ilex verticillata (winterberry)

Morella spp. (formerly Myrica spp., bayberries)

Prunus pumila, P. besseyi (sand cherries)

Pyracantha spp. (pyracanthas)

Rubus spp. (raspberries and blackberries)

Sambucus canadensis (American elder)

Vaccinium spp. (blueberries)

Viburnum spp. (viburnums)

Evergreen Shrubs

Cotoneaster spp. (cotoneasters)

Ilex spp. (hollies)

Mahonia aquifolium (Oregon grape)

Taxus cuspidata (Japanese yew)

Deciduous Trees

Amelanchier spp. (serviceberries)

Carya spp. (hickories)

Celtis spp. (hackberries)

Cornus florida (flowering dogwood)

Crataegus spp. (hawthorns)

Diospyros virginiana (common persimmon)

Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

Fraxinus americana (white ash)

Prunus spp. (cherries)

Malus spp. (crabapples)

Morus spp. (mulberries)

Sorbus spp. (mountain ashes)

Quercus spp. (oaks)

Evergreen Trees

Ilex opaca (American holly)

Juniperus spp. (junipers)

Picea spp. (spruces)

Pinus spp. (pines)

Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas fir)

Tsuga canadensis (Canada hemlock)

Of course, there is a flip side to landscaping for the birds, especially if you grow berries for your family. Bird netting may be a necessity if you don’t want to share your cherries and blueberries with your feathered friends. Fortunately, netting and other simple techniques—such as growing yellow-fruiting rather than red cherries—will prevent or minimize damage. (For more on controlling birds, see the Animal Pests entry.) But most seed-and fruit-eating birds favor wild food sources and are drawn to gardens only for their relative abundance of insects.

BLACKBERRY

See Brambles

BLANKET FLOWER

See Gaillardia

BLEEDING HEART

See Dicentra

BLUEBELLS

See Mertensia

BLUEBERRY

Vaccinium spp.

Ericaceae

Blueberries are among North America’s few cultivated native fruits. They are one of the most popular fruits for home gardeners for their ornamental value, pest resistance, and delicious berries. Some gardeners think they’re hard to grow because they require acid soil, but that requirement is actually quite easy to meet.

Types of Blueberries

Northerners grow two species of blueberries: Vaccinium corymbosum, highbush, and V. angustifolium, lowbush. Southern gardeners usually raise V. ashei, rabbiteye blueberry. All three species and their cultivars bear delicious fruit on plants with beautiful white, urn-shaped flowers and bright fall color.

Lowbush blueberries: Although the fruit of the lowbush blueberry is small, many people consider its flavor superior to that of other blueberries. These extremely hardy plants are good choices for the North. They bear nearly a pint of fruit for each foot of row. Lowbush plants spread by layering and will quickly grow into a matted low hedge. Native lowbush blueberries are the most hardy, especially with snow to protect them in Northern locations. Zones 2–6.

Highbush blueberries: Highbush are the most popular home-garden blueberries. Most modern varieties grow about 6 feet tall at maturity, and each bush may yield 5 to 20 pounds of large berries in mid to late summer. Crosses between highbush and lowbush species have resulted in half-high varieties such as ‘Northland’ and ‘Northblue’. These large-fruiting plants grow 1½ to 3 feet tall, a size that is easy to cover with bird-proof netting or with burlap (for winter protection). Highbush blueberries vary in hardiness, but many cultivars grow well in the North if you plant them in a sheltered spot. Some growers raise them in large pots and store them in an unheated greenhouse or cold frame for winter. Good varieties for the North include ‘Bluecrop’ and ‘Jersey’. Gardeners in the South and Pacific Northwest should choose varieties with a low chilling requirement, such as ‘Misty’ and ‘Sunshine Blue’. Zones 3–8.

Rabbiteye blueberries: Rabbiteyes are ideal for warmer climates. They’ll tolerate drier soils than highbush plants can, although they may need irrigation during dry spells. The plants grow rapidly and often reach full production in 4 to 5 years. Most modern varieties grow up to 10 feet tall and may yield up to 20 pounds of fruit per bush; some are hybrids between rabbiteye and highbush blueberries. Rabbiteyes and their hybrids are not reliably hardy north of Zone 7. They do not grow well in areas that are completely frost free, however, because they need a chilling period of a few weeks to break dormancy and set fruit. Zones 7–9.

Planting

Blueberries are particular about their growing conditions, so be sure to choose a suitable spot. They need a moist but well-drained, loose, loamy, or sandy soil with a pH somewhere in the range of 4.0 to 5.5 (the specific range depends on which type you want to grow). Test your soil before planting. If you need to reduce the pH, you can do so by working in lots of composted pine needles or oak leaves, or compost made from pine, oak, or hemlock bark. (You want the soil around the plants’ roots to be about a fifty-fifty mix of your soil and compost. If you can’t get a supply of the proper compost, you can add moist sphagnum peat moss to the planting bed in its place. All of these acidic organic materials will help lower pH.

Adding elemental sulfur is another acceptable method (1 to 7 pounds per 100 square feet of garden space, depending on your soil test results), but bear in mind that the sulfur will harm the mycorrhizae that associate with blueberry roots to aid their growth (for more about mycorrhizae, see the Soil entry). Avoid using the commonly prescribed aluminum sulfate, a chemical source of sulfur that is toxic to many soil organisms and changes the flavor of the fruit. For more information on adjusting soil pH, see the pH entry.

Because most blueberries are not self-fertile, you must plant at least two different cultivars to get fruit, and three are even more effective for good cross-pollination. Plant different cultivars near each other, as the blossoms are not especially fragrant and do not attract bees as readily as many other flowers. If you have a large plot set aside for blueberries, try interplanting the cultivars. Keep good records of your plantings, so that if you lose a cultivar you’ll be able to replace it with a kind that’s different from the surviving plants. Blueberries grow slowly and don’t reach full production until they’re 6 to 8 years old, so get a head start with 2- or 3-year-old plants.

After enriching the soil and making sure it’s acidic enough for blueberries, cultivate it thoroughly to allow the roots to penetrate easily. Blueberries are shallow-rooted, so all the nutrients and moisture the plants need must be available in the top few inches of soil.

In spring or fall, set highbush and rabbiteye blueberries 5 feet apart in rows spaced 7 to 9 feet apart. Set lowbush plants 1 foot apart in rows 3 feet or more apart. Water your plants with a liquid organic fertilizer such as compost tea or fish emulsion directly after planting and once a week for the next 3 to 4 weeks. See the Compost entry for instructions for making compost tea.

Maintenance