HAMAMELIS

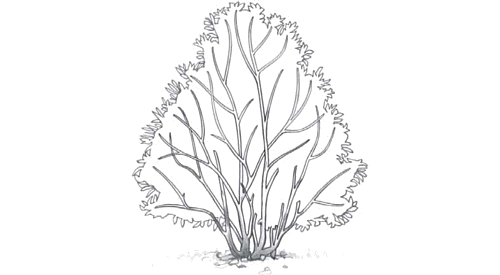

Witch hazel. Deciduous fall- or winter-flowering shrubs and small trees.

Description: Hamamelis vernalis, vernal witch hazel, a native species, grows 6 to 10 feet tall and can spread wider than its height. Fragrant yellow to red flowers appear in late winter to early spring and are showy for almost a month. Golden yellow fall foliage color is very showy. Zones 4–8.

H. virginiana, common witch hazel, another native, grows 15 to 20 feet tall and wide. Its spicy-scented, saffron yellow flowers unfurl as its clear yellow fall foliage is dropping.

H. mollis, Chinese witch hazel, reaches 10 to 15 feet tall and wide. It is spectacular in the landscape because its blooms appear in midwinter, often against a backdrop of snow. Zones 5–8.

All species have dull green, 2- to 6-inch leaves. In autumn, seed capsules can catapult seeds many feet.

How to grow: Grow witch hazels in partial shade, especially in the southern end of their range. Common witch hazel grows best in moist, humus-rich soil, with plenty of mulch. Prune only to remove branches that are dead, dying, crossing, or rubbing.

Landscape uses: Witch hazels make good specimens. Common witch hazel is lovely in a native planting.

HARDENING OFF

See Transplanting

HEDERA

Ivy. Evergreen woody vines.

Description: Hedera helix, English ivy, is a vigorous evergreen vine with shiny 3- to 5-lobed leaves, 2 to 5 inches long. Although this vine is very well known, it should be planted with caution because it is a nonnative species that can become invasive in some regions. It easily spreads beyond gardens, where it blankets woodlands, outcompetes native wildflowers, and overwhelms trees. Plants spread by stems that twine and attach by rootlets. Zones 5–9; some cultivars are hardy to Zone 4.

H. canariensis, Algerian or Canary ivy, is similar to English ivy but more tolerant of heat. Zones 9–10 and the milder parts of Zone 8. H. colchica, Persian ivy, displays large leaves and coarse growth. Zones 6–9. Both of these species also show invasive potential in warmer regions.

How to grow: If you choose to grow ivies, plant them on sites where buildings, paved walkways, or other structures will keep them contained. Start with rooted cuttings or transplants in spring or fall. Plants prefer moist, humus-rich, well-drained soils and tolerate acid or alkaline conditions. Give them partial or dense shade—they won’t tolerate full sun or hot sites. Ivies are relatively free of pest and disease problems. Prune regularly to keep them from spreading.

Landscape uses: Ivies serve well as groundcovers or climbing vines and are valued as low-maintenance plants. They are especially useful in dense shade, where little else will grow. Site them very carefully and keep them away from sites where they can spread to wooded areas. The vines have holdfasts on aerial rootlets that allow them to cling to brick and masonry walls. However, be aware that rootlets can work their way into cracks in the wall and eventually dislodge pieces of brick or stone.

Use small-leaved or variegated ivies to grow over topiary forms, plant them in containers or hanging baskets, or grow them as houseplants.

HEDGES

Plant a hedge for a privacy screen to block out unwelcome views or traffic noise or to add a green background to set off other plantings. Hedges also provide excellent wind protection for house or garden. Thick, tall, or thorny hedges make inexpensive and forbidding barriers to keep out animals—or to keep them in. Many plants make excellent hedges. Even tall or bushy annuals can make a temporary hedge; plant herbs such as lavender for an attractive low hedge.

Shaping a hedge. Prune a hedge so that its base is wider than the top. This allows light to reach all parts of the plants and keeps your hedge growing vigorously.

A formal hedge is an elegant, carefully trimmed row of trees or shrubs. It requires frequent pruning to keep plants straight and level. The best plants for formal hedges are fine leaved and slow growing—and tough enough to take frequent shearing. An informal hedge requires only selective pruning and has a more natural look. A wide variety of plants with attractive flowers or berries can be used.

Planting and Pruning

It’s best to plant young plants when starting a hedge. Full-grown specimens are more apt to die from transplanting stress in the early years, and finding an exact replacement can be difficult. It’s easier to fill a gap in an informal hedge.

For an open, airy hedge of flowering shrubs, allow plenty of room for growth when planting. For a dense, wall-like hedge, space the plants more closely. You may find it easier to dig a trench rather than separate holes. To ensure your hedge will be straight, tie a string between stakes at each end to mark the trench before digging. See the Planting entry for details on preparing planting holes and setting plants.

Broad-leaved plants used as a formal hedge need early training to force dense growth. For a thick, uniform hedge, reduce new shoots on the top and sides by one third or more each year until the hedge is the desired size. Cutting a formal hedge properly is a challenge. Stand back, walk around, and recut until you get it straight—just like a haircut. Shear often during the growing season to keep it neat.

Needled evergreens require a different technique. Avoid cutting off the tops of evergreens until they reach the desired height. Shear sides once a year, but never into the bare wood. See the Evergreens entry for more pruning tips.

HEDGE PLANTS

Most hedges are shrub or tree species; this list is a mix of common and uncommon hedge plants. An asterisk (*) indicates a plant for a formal hedge.

Evergreen Trees

Chamaecyparis lawsoniana (lawson cypress)

Juniperus spp. (junipers)

Prunus laurocerasus (English laurel)*

Tsuga canadensis (Canada hemlock)*

Deciduous Trees

Carpinus betulus (hornbeam)*

Crataegus spp. (hawthorns)*

Fagus spp. (beeches)

Evergreen Shrubs

Buxus spp. (boxwoods)*

Cotoneaster spp. (cotoneasters)*

Eunoymus spp. (euonymus)

Ilex crenata (Japanese holly)*

Ligustrum spp. (privets)*

Lonicera spp. (shrub honeysuckles)*

Mahonia spp. (Oregon grapes)

Taxus spp. (yews)*

Deciduous Shrubs

Chaenomeles speciosa (Japanese quince)

Forsythia × intermedia (forsythia)

Ligustrum spp. (privets)*

Philadelphus spp. (mock oranges)

Rosa spp. (shrub roses)

Viburnum spp. (viburnums)

Prune informal hedges according to when they bloom. Do any needed pruning soon after flowering. Use thinning cuts to prune selected branches back to the next limb. Heading cuts that nip the branch back to a bud encourage dense, twiggy growth on the outside. To keep informal hedges vigorous, cut 2 to 3 of the oldest branches to the ground each year.

For fast, dense growth, prune in spring. This is also a good time for any severe shearing or pruning that’s needed. For more about when and how to prune, see the Shrubs and the Pruning and Training entries.

HEIRLOOM PLANTS

Heirloom plants are most often thought of as old-time varieties of vegetables that come true from seed. That means that they’re open-pollinated, so (assuming you don’t plant other cultivars that could cross-pollinate nearby) you can save seed from your plants every year for the following year’s garden. In addition to wonderful heirloom vegetables, most cottage-garden flowers and herbs fall in this category, too. Of course, many plants have been lovingly passed down through the generations as cuttings, and even the hybrids that replaced most open-pollinated plants in commerce now boast some old “heirloom” cultivars of their own. But usually, “open-pollinated” continues to be the hallmark of herbaceous heirloom plants.

Some famous heirlooms have been sold and passed down in families or communities for hundreds of years; others date just to the early 1900s. What they all have in common is that backyard gardeners have prized them for their beauty, flavor, fragrance, or productivity. Because home gardeners thought highly enough of these plants to save seed from them year after year, we can still enjoy them today.

Characteristics: Heirloom fruits and vegetables are often not suited to large-scale production. Many types don’t ripen all at once so they can’t be harvested mechanically. They often don’t keep well during shipping and storage and many of them don’t have a consistent appearance. They may even look a little odd, like some of the warty-skinned melons or striped green tomatoes.

But heirlooms are often ideal for home gardeners. Many heirloom crops have a more pleasing taste and texture than their hybrid replacements, and many spread their harvest over a longer period so families can enjoy picking just what they need for each day’s meals rather than having to harvest a bumper crop all at once. If grown for years in one locality, the heirlooms have adapted to the climate and soil conditions of that area and may outproduce modern cultivars. Others may be less productive than today’s hybrids, but offer greater disease and insect resistance, which is invaluable to organic gardeners. (On the other hand, some heirlooms are less resistant than hybrids bred specifically to resist particular diseases.) Heirloom plants also add interest to garden and table, with a wide range of shapes, colors, and tastes unavailable in modern cultivars.

Heirloom plants are also a tangible connection with the past. Like fine old furniture and antique china, the garden plants of earlier generations draw us closer to those who have grown them before us. Some heirloom cultivars have fascinating histories. ‘Mostoller Wild Goose’ bean, said to have been collected from the craw of a goose shot in 1864 in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, was once grown by Cornplanter Indians. ‘Hopi Pale Grey’ squash is a Pueblo Indian legacy that was almost lost to cultivation, and remains one of the most sought-after winter squashes. ‘Anasazi’ corn, found in a Utah cave, is thought to be more than 800 years old. And many gardeners have heard the story of ‘Radiator Charley’s Mortgage Lifter’ tomato, a huge, meaty cultivar that helped its discoverer, an unemployed mechanic, pay off his mortgage during the Depression.

Cultivars like these are eagerly sought by both gardeners and collectors, who maintain them for their historic value just as archivists maintain old papers and books. See the list at right for other well-known examples.

Genetic diversity: As fewer seed companies remain in existence and those that survive offer a dwindling number of cultivars, there’s an even more vital reason for growing old cultivars: These open-pollinated heirloom plants represent a vast and diverse pool of genetic characteristics—one that will be lost forever if these plants are allowed to become extinct. Even cultivars that seem inferior to us today may carry a gene that will prove invaluable in the future. One may contain a valuable but yet undiscovered substance that could be used in medicine. Another could have the disease resistance vital to future generations of gardeners and plant breeders.

The federal government maintains the National Seed Storage Laboratory in Fort Collins, Colorado, as part of its commitment to maintaining genetic diversity, but the task of preserving seed is so vast that the government probably cannot do a complete job on its own. Heirloom gardeners recognize the importance of maintaining genetic diversity, and many feel a real sense of urgency and importance about their own preservation work. Thanks to them, to seed companies that remain committed to offering open-pollinated heirlooms to the public, and to organizations like Seed Savers Exchange that are dedicated to maintaining diversity in the garden, the future of heirloom plants looks bright.

Famous Heirlooms

Here is just a sampling of the best-known heirloom cultivars. This selection just skims the surface to whet your appetite:

Beans: ‘Cherokee Trail of Tears’, ‘Dragon Tongue’, ‘Hutterite Soup’, ‘Jacob’s Cattle’, ‘Mayflower’, ‘Old Homestead’

Corn: ‘Black Aztec’, ‘Country Gentleman’, ‘Golden Bantam’, ‘Stowell’s Evergreen’

Cucumbers: ‘Boston Pickling’, ‘Chinese Yellow’, ‘Lemon Cuke’, ‘White Wonder’

Lettuce: ‘Amish Deer Tongue’, ‘Black-Seeded Simpson’, ‘Merveille des Quatre Saisons’, ‘Parris Island Cos’, ‘Tom Thumb’

Squash: ‘Rouge Vif d’Etampes’, ‘Turk’s Cap’, ‘White Scallop’, ‘Winter Luxury Pie Pumpkin’

Tomatoes: ‘Amish Paste’, ‘Bloody Butcher’, ‘Brandywine’, ‘Cherokee Purple’, ‘German Lunchbox’, ‘Green Zebra’, ‘Mule Team’, ‘Persimmon’

Watermelons: ‘Charleston Gray’, ‘Dixie Queen’, ‘Georgia Rattlesnake’, ‘Moon and Stars’, ‘Stone Mountain’

Getting started: If you’d like to start growing heirloom plants in your garden, try ordering seed from small specialty seed suppliers that carry old cultivars. Also, you can contact nonprofit organizations that work with individuals to preserve heirloom plants, such as the Seed Savers Exchange. Some gardening magazines also have a seed swap column. See Resources on page 672 for contact information for seed exchanges. For directions on how to save seeds from your garden, see the Seed Starting and Seed Saving entry.

HELIANTHUS

Sunflower. Summer- to fall-blooming annuals and perennials.

Description: Helianthus annuus, common sunflower, is an annual that lights up gardens with single or double daisies in shades of cream, yellow, orange, and red-brown on plants 2 to 10 feet tall or taller. For more details, see the Sunflower entry.

H. × multiflorus, many-flowered sunflower, is a perennial that bears 3- to 5-inch golden blooms on upright, bushy plants to 5 feet. Blooms appear from late summer to fall. Zones 4–8.

How to grow: Start annuals indoors a few weeks before the last frost, or sow directly in full sun and average to rich, moist but well-drained soil. Water and fertilize regularly. Provide similar growing conditions for perennials; plant in spring. Divide overgrown clumps in fall every 3 or 4 years. Sunflowers are usually drought tolerant once established.

Landscape uses: Grow in borders for summer and fall color, in informal and meadow gardens, and in cutting gardens.

HELLEBORUS

Hellebore. Winter- to early-spring-blooming perennials.

Description: Hellebores bear 2- to 3-inch, shallow bowl-shaped flowers and 1-foot palm-shaped evergreen leaves. Helleborus foetidus, green-flowered or stinking hellebore, bears striking clusters of chartreuse flowers held well above blue-gray or dark forest green leaves. ‘Wester Flisk’ is an outstanding cultivar. Zones 5 (with protection) or 6–9.

H. niger, Christmas rose, bears white flowers in winter or early spring among 1-foot mounds of foliage; ‘Potter’s Wheel’, ‘Blackthorn Strain’, and ‘Nell Lewis’ are outstanding. Zones 3–8.

H. orientalis, Lenten rose (more often orientalis hybrids, H. × hybridus), blooms in early spring, with white, green, pink, yellow, purple, maroon, or almost black flowers among handsome, 1½-foot shiny green leaves. Flowers are often speckled with a contrasting color, and some cultivars, such as ‘Party Dress’, have double flowers. Many outstanding cultivars and strains are available. The hybrid Lenten rose (H. × hybridus) was named Perennial Plant of the Year for 2005 by the Perennial Plant Association. Zones 4–9.

How to grow: Set out pot-grown or small plants in spring or fall. Divide these slow-to-establish but long-lived plants in spring, but only when you want new plants. They thrive in partial to full shade and well-drained, moisture-retentive, humus-rich soil. Keep out of drying winter winds. Established hellebores can self-sow profusely; transplant seedlings to their permanent positions in spring. (Note that a seedling may take two to five years to reach flowering size, so be patient. These long-lived plants are worth the wait.)

Landscape uses: Allow to naturalize in woodland plantings and among shrubs. Feature with early snowdrops and crocuses. A perfect complement to other shade plants such as hostas, ferns, wild gingers (Asarum spp.), bleeding hearts (Dicentra spp.), heucheras, and astilbes.

HEMEROCALLIS

Daylily. Mostly summer-blooming perennials; some bloom in spring and fall.

Description: Daylilies bear 2- to 8-inch-wide trumpet-shaped flowers in tones of almost every floral color except pure white and blue. Individual blooms last for only 1 day, though plants produce many buds, which provides a long display period. Flowers are borne on 1- to 6-foot (but usually 2½- to 3½-foot) top-branched, strong stems above fountainlike clumps of strap-shaped, roughly 2-foot-long, medium green leaves. Famous cultivars include the classic tall, fragrant, yellow ‘Hyperion’, gold ‘Stella de Oro’, and reblooming, lemon-yellow ‘Happy Returns’. Zones 3–9.

How to grow: Plant or divide daylilies any time from spring to fall, though early spring and early fall are best. Divide 4- to 6-year-old clumps by lifting the entire clump from the ground and inserting two digging forks back-to-back, pulling them apart to split the tight root mass. Replant as single, double, or triple “fans.” Daylilies grow in sun or partial shade. Plant in average to fertile, well-drained, moisture-retentive soil (though plants will tolerate drought). Routinely deadhead spent blooms, which otherwise collect on the stalks and spoil the display. Watch for thrips, which brown and disfigure the buds; control them with soap spray or by removing infested flowers.

Landscape uses: Grow as specimens or groups in borders, or showcase daylilies in beds of their own. Many tougher, older cultivars make excellent groundcovers and bank plantings to control erosion and weeds. They also look beautiful planted along a fence or stone wall. Try showy rebloomers (like the ‘Returns’ series) as specimen plants in half-barrel containers.

HEMLOCK

See Tsuga

HERBS

Every gardener should grow at least a few herbs, even if only in pots on a sunny porch. Herbs contribute to our cuisine and our well being; serve as decorative additions in gardens, bouquets, and wreaths; and fascinate us with their rich history and lore.

The word herb has different meanings to botanists and herb gardeners. For the botanist, an herb is basically any seed-bearing plant that isn’t woody; it’s where our word herbaceous comes from, as in herbaceous perennial. But for herb gardeners, what distinguishes an herb from other plants is its usefulness. As Webster’s puts it, an herb in this sense is “a plant or plant part valued for its medicinal, savory, or aromatic qualities.”

Above all, whether used for flavorings, fragrances, medicines, crafts, dyes, or teas, herbs are truly useful plants. They’re also among the most familiar garden plants, because they have been part of our daily lives since the dawn of human history, long before humans began making gardens. From the beginning, people recognized the abilities of certain plants to heal and to promote health. From there, it was a short step to flavoring food and scenting the dwelling place.

Gardening with Herbs

There are nearly as many ways to incorporate herbs into your garden as there are herbs to choose from. A traditional herb garden is delightful, but herbs add interest to flower gardens, too. You can mix herbs into plantings of perennials or annuals, for example. One advantage of growing herbs apart from ornamentals, though, is that you won’t spoil the flower garden display when you harvest your herbs.

Herb growing can be as simple or as complicated as you choose to make it. Most herbs are easy to grow—they demand little (typically full sun and good drainage) and give a lot. You can grow herbs successfully in anything from a simple arrangement of pots to a stylized formal garden. Only a few types of herbs are prima donnas that demand coddling. Also, some that are not hardy in the North must be brought indoors for winter.

Vegetable Gardens

If your goal is to grow herbs in quantity, it makes sense to plant them in rows or beds in your vegetable garden for ease of care and harvest. Plants such as oregano, savory, santolina, thyme, culinary sage, and lavender do best in full sun in well-drained soils to which lime and grit have been added. Place them on specially prepared ridges or in raised beds. Angelica can be settled into a wettish spot. Dill, cilantro (coriander), parsley, chives, garlic chives, French tarragon, mints, and basils will thrive in a sunny site in well-drained soil containing lots of organic matter.

Herbs are often used as companion plants in the vegetable garden. According to folklore, in some cases backed by scientific studies, certain herbs can either aid or hinder vegetable growth. Herbs also help deter pests. And of course, they add beauty to your vegetable beds. See page 314 and the Companion Planting entry for more details.

Herbs and Flowers

Many herbs are suitable for a mixed border or bed—a flower garden that combines perennials, annuals, and shrubs. You may already have some herbs in your garden, although you may think of them as flowers or foliage plants. In fact, roses such as the Apothecary’s rose (Rosa gallica var. officinalis) and damask rose (R. damascena) have been grown for centuries for their medicinal and fragrant qualities.

English lavender cultivars such as ‘Hidcote’ or ‘Munstead’ are always welcome among the flowers in beds or borders. Pure blue, silky flowers on delicate wiry stems make blue flax (Linum perenne) a favorite in flower beds. Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) is another herb often used in mixed borders. Its lacy, bright green foliage sets off small, pure white single or double daisies. Catmints (Nepeta spp.), with sprays of blue-lavender flowers, pungent, gray-green leaves, and a tufted habit, is lovely with lilies and roses.

Many gray-leaved herbs, such as the artemisias (Artemisia spp.), lamb’s ears (Stachys byzantina), and Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia), with its silvery foliage and misty blue flowers, are useful for separating and blending colors in the garden. Even a culinary workhorse like dill can be used to fine effect in the mixed border. Its delicate, chartreuse flowers and lacy foliage add an airiness to any planting.

Herbs in Containers

Herbs and containers are a happy combination, especially for a gardener short on space, time, or stamina. Maintenance chores—except for watering—are eliminated or much reduced. Even if your garden has plenty of space, a potted collection adds interest to a sunny porch, patio, or deck. Keep that “sunny” aspect in mind when planning your container herb garden—most herbs need full sun and good drainage whether they’re grown in pots or in the ground. (Mints are an exception, fond as they are of moist soil.) In fact, one great reason to grow herbs in containers is if much of your yard is in shade but your patio, deck, or dooryard is sunny.

An assortment of terra-cotta pots brimming with herbs used for cooking makes a charming—and useful—addition to a kitchen doorstep. Or try a sampler of mints in a wooden half-barrel—the notorious perennial spreaders stay in control, will come back year after year, and are handy when you’re ready to brew a pot of tea. Hanging baskets of nasturtiums will add delightful color to your collection of container herbs, and the leaves, flowers, and spicy buds are all edible. For information on potting soil mixes for container plants, see the Container Gardening and Houseplants entries.

Some tender herbs are often grown—or at least overwintered—in containers because they aren’t hardy and won’t survive Northern winters. These include rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), sweet bay (Laurus nobilis), myrtle (Myrtus communis), pineapple sage (Salvia elegans), and lemon verbena (Aloysia triphylla). See page 310 for directions on keeping these tender herbs from year to year.

Herbs for a Mixed Border

Many herbs will thrive in a sunny mixed bed or border with average to rich, well-drained soil. These herbs are showy enough to hold their own in any garden. Plants are perennials unless otherwise noted.

Achillea spp. (yarrows): yellow, white, red, or pink flowers; used medicinally and dried for herbal crafts

Calendula officinalis (pot marigold): annual with bright orange or yellow daisylike flowers; used medicinally and in cooking

Digitalis purpurea (common foxglove): biennial with tube-shaped pinkish purple or white flowers; formerly used medicinally (do not try this today!)

Echinacea purpurea (purple coneflower): rosy purple daisies with high, bristly centers; roots are used medicinally

Lavandula angustifolia (lavender): lavender or purple flowers; flowers and foliage used for fragrance and herbal crafts

Linum usitatissimum (flax): blue flowers; used medicinally

Monarda didyma (bee balm): shaggy rose or pink blossoms; dried blossoms and foliage used for tea, fragrance, and herbal crafts

Tropaeolum majus (garden nasturtium): annual with abundant flowers in shades of orange, yellow, and red; used in cooking and as a companion plant

Formal Herb Gardens

Most gardeners would probably include an exquisitely groomed formal herb garden on their wish list. But if you have the impulse to make a formal herb garden, bear in mind that they’re not for everyone. These carefully planned gardens with their neatly trimmed, geometric arrangements require both strength and time to keep them looking their best.

Knot gardens, in which miniature hedges in different colors and textures create the look of intertwining strands, are a classic feature of formal herb gardens. Dwarf boxwoods (Buxus spp.), lavender (Lavandula spp.), lavender cotton (Santolina virens and S. chamaecyparissus), and germander (Teucrium chamaedrys) are popular knot-garden plants. You can also mix textures and colors of mulches—brown cocoa shells, white marble chips, gray-blue crushed granite, and so on—to elaborate the knot garden. However, while knot gardens can be an intriguing challenge to plan and plant, even a modest version requires constant maintenance. Everything must be kept under control—constant trimming and shaping are essential, and all the plants must be in topnotch health if the knot pattern is to remain attractive.

If you’re ambitious enough to try a knot garden, keep it small, so that replacements and maintenance aren’t overwhelming. You’ll need to replace individual specimens in the clipped hedges that don’t make it through winter. Replacements can be hard to find in the same size as the plants that remain intact. If you have space, keep a few extra plants growing in a nursery bed or other out-of-the-way spot for just such emergencies.

Another type of formal herb garden consists of a pattern of squares or diamonds with contrasting borders. You can grow a different herb in each square, or grow alternating squares of the same herb—the key is to grow just one herb in each square—to make a pattern. The squares are tied together with either edgings of knot-garden plants forming a low, meticulously groomed hedge around each square, or by narrow pavings of bricks between the squares with wider brick paths typically dividing the garden into quadrants. Like a knot garden, a garden of this type requires a great deal of grooming and attention to detail.

Informal Herb Gardens

Perhaps one of the easiest and most rewarding ways to use herbs in the landscape is in an informal herb garden. An informal garden can be a free-form island bed, with the tallest herb plants in the center and the shortest around the edges. Or it could be more like a perennial border, set against a background such as a wall, hedge, fence, or building and defined with either straight or curved lines.

So many flowering plants have been used as herbs that even the most rigid purist—one who plants a garden of only traditional herbs—could enjoy plenty of color and texture. Such a garden also would have an abundance of fragrances, plus an added bonus of plenty of herbs to use in wreaths, potpourris, or other projects.

An informal garden of ornamental herbs could feature billows of poppies, yarrows, and lavenders (one herb nursery offers 46 species and cultivars!). Masses of painted daisies (Chrysanthemum coccineum), catmints (Nepeta spp.), artemisias, and flax (Linum spp.) might be backed by white spikes of Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum), tall foxgloves (Digitalis spp.), or Canadian burnet (Sanguisorba canadensis). For further textural interest, try the elegant leaves and umbels of angelica (Angelica archangelica), the shaggy blossoms of bee balm (Monarda didyma), and the fragrant, frothy plumes of white mug-wort (Artemisia lactiflora), one of the few artemisias with green leaves.

Herbs for Shady Gardens

Although most herbs require a sunny site, there are some herbs that will grow in shade. Provide these shade-loving herbs with loose, rich soil and plenty of moisture. This list includes herbs grown for fragrance, culinary uses, and teas. Many are American natives that were used medicinally. Grow them from seed or buy plants from nurseries that propagate their own stock, rather than gathering them from the wild.

Actaea racemosa (black snakeroot): spikes of small white flowers; roots used medicinally

Anthriscus cerefolium (chervil): white-flowered annual; culinary herb

Asarum canadense (wild ginger): attractive groundcover; used medicinally

Caulophyllum thalictroides (blue cohosh): blue berries (poisonous); roots used medicinally

Coptis groenlandica (common gold-thread): small shiny-leaved plant with threadlike yellow creeping roots used medicinally and for dye

Galium odoratum (sweet woodruff): low-growing plant with white flowers; excellent groundcover; dried foliage and flowers used for fragrance

Gaultheria procumbens (wintergreen): creeping evergreen with tasty leaves and berries; used medicinally and for teas

Hamamelis virginiana (common witch hazel): shrub with autumn flowers with petals like small yellow ribbons; used medicinally

Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal): thick yellow root used medicinally and for dye

Melissa officinalis (lemon balm): white-flowered mint-family member; used for fragrance and teas

Mentha spp. (mints): rampant-growing herbs with pungent foliage used medicinally and for fragrance and teas

Myrrhis odorata (sweet cicely): ferny, fragrant foliage; smells of licorice; culinary herb

Polygonatum spp. (Solomon’s seals): dangling bell-like flowers; roots used medicinally

Sanguinaria canadensis (bloodroot): white flowers in early spring; used medicinally

Viola odorata (sweet violet): violet, white, purple, rose, or blue flowers in spring; will spread; used for fragrance

Gray-leaved plants provide good contrast but avoid the artemisia cultivars ‘Silver King’ and ‘Silver Queen’ unless you confine them with a physical barrier. They are determined spreaders and quite aggressive. Two large, attractive silver artemisias that do not spread are ‘Lambrook Silver’ and ‘Powis Castle’. ‘Powis Castle’ is not reliably hardy north of Zone 6, but cuttings root easily during summer and can be kept in pots indoors during winter.

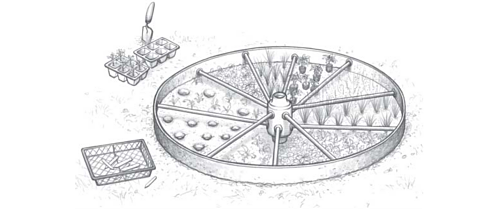

Herb wheel garden. Planting herbs in a wagon wheel frame creates a garden that’s as attractive as it is productive. Plant each pie-shaped section with a single type of herb, repeating pie sections for herbs you like best. If you like, choose a theme such as pizza, salsa, or salad herbs or herbs for dips.

Yarrows (Achillea spp.) have been used medicinally for ages and belong in any herb garden. They now come in wonderful colors—shades of rose, buff, apricot, and crimson, as well as their usual yellows, white, and pink. Still pretty in the garden are the old ‘Coronation Gold’, in deep yellow, and the pale lemon ‘Moonshine’. The flowers of ‘Coronation Gold’ dry particularly well for winter bouquets.

Include hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis) and anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) in an informal garden, too. Although members of the mint family, they spread by means of seeds instead of stolons. The ordinary hyssop is a bushy, 2-foot plant whose flowers come in blue, pink, or white. Anise hyssop is taller and produces dense spikes of bluish lavender flowers in August when perennial flowers are scarce.

Culinary sage and other salvias, rue, and orris (Iris ✕ germanica var. florentina) are other good choices for an informal garden.

Use low-growing or mat-forming herbs to front the tall and midsized plants. Try clove pinks (Dianthus caryophyllus), chives, santolinas (both green and gray), and thymes.

Growing Herbs

Herbs are generally undemanding plants. Given adequate light and good soil, they will produce well and suffer from few problems. Some herbs are perennials; others are annuals. Keep in mind that tender perennial herbs will behave like annuals in the Northern states unless they’re grown in containers and brought indoors for winter.

Annual Herbs

Common annual herbs are basil, chervil, cilantro (coriander), dill, summer savory, and parsley, which is actually a biennial that is grown as an annual. More-exotic annuals include Jerusalem oak (Chenopodium botrys, also called ambrosia and feathered geranium), safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), sweet Annie (Artemisia annua), and sweet marigold (Tagetes lucida), a substitute for French tarragon. Sweet marjoram (Organum majorana) is not hardy north of Zone 6, but it lives through winter in the South.

Plant seeds for chervil, cilantro (coriander), and dill outdoors where they are to grow, in spring or fall. These herbs are extremely difficult to transplant successfully. If you want a head start on outdoor planting, sow them in peat pots for minimum root disturbance at planting time. Sow sweet annie and Jerusalem oak outdoors in autumn.

Herb seedlings are often tiny and slower-growing than weeds, so it makes sense to start them indoors if you can. Start basil, marigolds, marjoram, and summer savory indoors in flats or pots, and move them to the garden when no more cold weather is expected. Parsley takes so long to come up that you might be better off starting it indoors, too. Outdoors, you will be down on your knees every day trying to sort out the baby parsley plants from the weeds, which germinate quickly and will always have a head start.

Some annual herbs, such as dill, self-sow so generously there is no need to plant them year after year if the plot where they are growing is kept weeded. If you allow a parsley plant to remain in the garden the second year and set seed, it, too, will self-sow. This makes for convenience and good strong plants as well, because self-sown plants are almost always sturdier than those started indoors under lights. For more information on starting herb seeds, see the Seed Starting and Seed Saving entry.

Perennial Herbs

Perennial herbs can be grown from seed, but they take longer to germinate than the annuals. It’s better to start out by buying young plants of perennial herbs such as mints, sages, and thymes. If you’re growing named cultivars that may not come true from seed, it makes even more sense to buy plants. Once you’ve gotten started, increase your supply by dividing plants such as mint or by taking cuttings, which works well for rosemary and myrtle. For more on propagating herbs, see the Division and Cuttings entries.

Many perennial herbs need no help once they’re established in your garden. Sweet woodruff (Galium odoratum) will supply you with bushels of foliage for potpourri while it covers the ground. Chamomile, chives, feverfew, garlic chives, lemon balm, and winter savory will self-sow eternally.

Horehound, oregano, and thyme usually sow some seedlings, but fennel and lovage seem to stay in one place without multiplying. Some of the catmints (Nepeta spp.) self-sow; others don’t.

You may prefer to propagate certain perennial herbs by means of cuttings because they are especially beautiful, fragrant, or flavorful forms or cultivars. (Plants propagated from seed don’t always resemble their parents, whereas those from cuttings do.) If you have a fine lavender such as ‘Hidcote’ and you would like to have more without paying for more plants from the nursery, take 3- to 4-inch cuttings of the semihard tips and gently remove the lower leaves, Press the cuttings into a mixture of damp peat and sand in a light but not sunny spot, cover with a cloche or jar, and start yourself some new plants. You can also do this with thymes, taking cuttings from a silvery or variegated plant or any one that you especially like. Lemon verbena is sterile and must be propagated this way. Luckily, it roots readily.

French tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus var. sativa) must also be purchased as a plant, since it never sets viable seed. The so-called Russian tarragon offered as seed has no culinary value. When French tarragon is grown in sun or part sun and in light, well-watered but well-drained soil, it usually thrives and spreads enough to divide one plant into many each spring. It is hardy at least through Zone 5. However, if you do not succeed with it, due to severe cold or to high summer temperatures in your area, try the annual marigold from Mexico and South America called sweet marigold (Tagetes lucida). It makes an excellent substitute.

General Care

Like nearly all plants, herbs require well-drained soil. While most do best in full sun, they will accept as little as 6 hours of sunlight a day. Incorporate compost or other organic matter into the soil regularly. Cultivate carefully to keep out weeds. Mulch everything except the Mediterranean plants (marjoram, oregano, rosemary, sage, winter savory, and thyme) with a fine, thick material such as straw that neither acidifies the soil nor keeps out the rain. Avoid pine bark (chipped or shredded) and peat. Mediterranean plants prefer being weeded to being mulched, since they are used to growing on rocky hills with no accumulation of vegetable matter around their woody stems. In the colder areas of the country, protect your plantings of catmint, horehound, lavender, rue, thyme, winter savory, and sage with evergreen boughs in winter.

Gardeners who grow their plants out in the sun and wind will have little trouble with disease or insect damage. Basil is sometimes subject to attack by chewing insects, but if you follow good cultural practices and grow enough plants, the damage can be ignored. You’ll rarely have the need to take measures to control insect pests on herbs. It’s best never to apply botanical insecticides to culinary herbs.

Overwintering Tender Perennials

To overwinter frost-tender herbs such as rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), sweet bay (Laurus nobilis), myrtle (Myrus communis), pineapple sage (Salvia elegans), scented geraniums (Pelargonium spp.), and lemon verbena (Aloysia triphylla), you can either grow them permanently in pots or take cuttings of plants at the end of the season, root them, then pot them and hold them over winter indoors until the following spring. This latter method works well for nonwoody herbs like basils and pineapple sage.

Shrubby or woody plants, like sweet bay or rosemary, are best grown in pots so they can be moved indoors when winter cold threatens. In summer, set them in a spot outdoors where they get morning but not afternoon sun. Some gardeners take their tender herbs out of their winter pots and put them into the ground for summer. However, this is an extremely stressful procedure for the plants, because the roots they send out in garden soil have to be chopped back in fall and forced into pots for winter.

During winter months indoors, keep herbs in a cool, sunny window, and make sure they never dry out. Rosemary especially must be watered frequently, although never left to sit in water. Verbenas will shed most or all of their leaves during winter. Water them very sparingly until early spring, when tiny leaf buds begin to appear along their branches.

These plants don’t really object to being grown in pots, but they don’t tolerate being indoors very well. You may have to help them fight off bugs and diseases during winter months. Potted herbs in the house may become afflicted with scale, aphids, or other pests. (Scented geraniums are the exception; these plants tend to shrug off pests.) Keep a close watch for signs of infestation. See the Houseplants entry for information on controlling these pests. In spring, move the plants outside. Within a few days, their relief will be visible, and they’ll start growing happily again.

Before bringing herbs in for winter, turn them out of their pots and put them into larger ones, adding new soil mixed with compost. When, after some years, the pots have reached the limit of what you want to lift, turn out the plants and root-prune them. If the roots form a solid, pot-shaped lump (as they certainly will in the case of rosemary), take a cleaver or large kitchen knife and slice off an inch or two all the way around. Fill in the extra space with fresh soil and compost. Cut back one quarter to one third of the top growth to balance what you have removed from the bottom.

Harvesting and Storing

Cut and use your herbs all summer while they are at their very best. The flavor of the herb leaves is at its peak just as the plants begin to form flower buds. Cut herbs in midmorning, after the sun has dried the leaves but before it gets too hot. You can cut back as much as three-quarters of a plant without hurting it. (When harvesting parsley, remove the outside leaves so that the central shoot remains.) Remove any damaged or yellow foliage. If the plants are dirty, rinse them quickly in cold water and drain them well.

You will want to preserve some herbs for use during winter months. Drying is an easy way to preserve herbs, although you can also freeze them in plastic bags or preserve them in olive oil.

Air drying: Dry herbs as quickly as possible in a dark, well-ventilated place. Attics and barns are ideal, but any breezy room that can be kept dark will do. Hang the branches by the stems, or strip off the leaves to dry them on racks through which the air can circulate. Drying on racks is the best way to handle large-leaved herbs such as sweet basil or comfrey. It’s also good for drying rose petals or other fragrant flowers for potpourris.

To keep air-dried herbs dust free and out of the light while drying, you can cover them with brown paper bags. Tie the cut herbs in loose bunches, small enough so that they don’t touch the sides of the bag, then tie the bag closed around the ends of the stems. Label each bag.

After a few weeks, test for dryness. When the leaves are completely dry and crisp, rub them off the stems and store them in jars out of the light.

Dehydrating: If you have an electric dehydrator, it’s an easy, ideal tool for drying your herbs. Strip off the leaves and place them on the dehydrator trays so they’re not touching, and follow your dehydrator’s instructions for the appropriate time and setting.

Oven drying: You can also dry herbs on racks made of metal screening in a gas oven that has a pilot light. Turn them twice a day for several days. Or dry in an oven at very low heat—150°F or lower. When herbs are crisp, remove the leaves from the stems and crumble them into jars.

Microwave drying: Microwave-dried herbs retain excellent color and potency. Start by laying the herb foliage in a single layer on a paper towel, either on the oven rack or on the glass insert. Cover the leaves with another paper towel and microwave on high for 1 minute. Then check the herbs, and if they are still soft, keep testing at 20- to 30-second intervals. Microwave ovens differ in power output, so you’ll have to experiment. Keep track of your results with each kind of herb.

Microwave drying is a bit easier on plant tissue than oven drying, because the water in the herb leaves absorbs more of the energy than the plant tissue does. The water in the leaves gets hot and evaporates—that’s why the paper towels become damp during the drying process—leaving drying plant tissue behind. The plant tissue heats up a little because of the contact with the water, but the water absorbs most of the heat. In a conventional oven, all the plant material gets hot, not just the water.

Using Herbs

If you have only a tub or two in which to grow herbs, you might plant a few culinary herbs or lavender for fragrance. If you have a big garden, you can experiment with medicinal plants as well as with material to dry for colorful, fragrant bouquets, wreaths, and potpourris.

Herbs for Cooking

If you’re not accustomed to using herbs in cooking, start out by exercising restraint. If you overdo it, you might find you have overwhelmed the original flavor of the meat or vegetable whose flavor you meant to enhance. Remember that ounce for ounce, dried herbs have more potent flavor than fresh ones. Study cookbooks’ herb recommendations, and when you’ve learned the usual combinations (French tarragon with fish or chicken, or basil with tomatoes and eggplant, for instance), experiment on your own. You could invent some new and wonderful dishes. See the list on the opposite page for ideas to get you started.

Herbs for Teas

While you’re gathering herbs for the kitchen, include some to use for tea. Herbal teas can be soothing, stimulating, or simply pleasant. Many of them are wonderful aids to digestion or for allaying cold symptoms. Some, such as lemon balm, pineapple sage, and lemon verbena, make refreshing iced teas or additions to iced drinks.

You can make herb tea with dried or fresh leaves, flowers, or other plant parts. To make herb tea, place leaves into an herb ball in an earthenware or china pot or mug. Start with 1 tablespoon of dried herbs or 2 tablespoons of fresh herbs per cup, and adjust the quantity to suit your own taste as you gain experience. Then add boiling water, and steep for 5 to 10 minutes before removing the herb ball and serving the tea.

One word of caution: Not all herbs are suitable for making tea. If you’re experimenting with making herbal teas, remember that some herbs can make you ill if ingested. Research before you brew. See the list on page 314 of herbs you can safely brew and sip.

Herbs for Fragrance

Flowers release their perfume into the air so freely, you need only walk past them to enjoy the scent of roses, lilacs, honeysuckle, clove pinks, or any other highly fragrant flower. Occasionally, we can detect the scent of lavender or thyme when they are baking in the hot sun. But plants with aromatic leaves do not, as a rule, release the odor of their oils unless you rub a leaf or walk on the plant or brush against the branches while working around them.

The leaves of scented geraniums (Pelargonium spp.)—just one example of the many fragrant-foliaged herbs—are wonderful to rub between your fingers. They come in a wide variety of scents, including lemon rose, lemon, mint, nutmeg, rose, and ginger. Their many different fragrances, and their leaf and flower variations, make them fascinating to collectors and gardeners alike.

Culinary Herbs

There’s a wide range of herbs for adding flavor to everything from salad dressing to dessert. This list includes popular herbs for livening up your meals.

Angelica (Angelica archangelica): in salads, soups, stews, desserts

Caraway (Carum carvi): with vegetables or in soups, stews, or bread

Chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium): in soups and stews, or with fish or vegetables

Chives (Allium schoenoprasum): add to soups, salads, and sandwiches

Coriander (Coriandrum sativum): in salad, stew, or relish; popular in Thai and Mexican cooking

Dill (Anethum graveolens): with fish or vegetables; in salads or sauces; seed used for pickling

French tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus var. sativa): in salads or sauces; with meat, fish, or vegetables

Garlic (Allium sativum): use in all kinds of dishes, except desserts

Garlic chives (Allium tuberosum): add to soups, salads, and sandwiches

Lovage (Levisticum officinale): use like celery, in soups, stews, salads, or sauces

Mints (Mentha spp.): in jellies, sauces, or teas; with meats, fish, or vegetables

Oregano (Origanum heracleoticum): in sauces, or with cheese, eggs, meats, or vegetables

Parsley (Petroselinum crispum): use in all kinds of dishes, except desserts

Rosemary (Rosemarinus officinalis): with meat or vegetables; in soups or sauces

Sage (Salvia officinalis): with eggs, poultry, or vegetables

Savories (Satureja spp.): in soups or teas, or with vegetables, especially beans

Sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum): with meats or vegetables, in sauces, pesto, and salads

Sweet bay (Laurus nobilis): in soups, stews, or sauces

Sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana): use like oregano

Thyme (Thymus vulgaris): with meat or vegetables

Lavender, lemon balm, lemon verbena, scented geraniums, rosemary, and sweet woodruff are among the best-known herbs grown for fragrance. All can be preserved by air drying (see page 311 for directions). For more suggestions of herbs to grow for fragrant flowers, foliage, or fruit, see the list on page 315.

Making sachets and potpourri are two good ways to preserve the scent of herbs to add fragrance to linens or to the rooms of your house. Sachets are made with combinations of dried herb leaves and frequently lavender blossoms as well as rose petals, crumbled or ground. You can dry rose petals by spreading them on sheets or screens in a dark, airy place. Petals of apothecary’s rose (Rosa gallica var. officinalis) are the most fragrant.

Tea Herbs

Of all the uses that herbs have, the one many people enjoy most is making and drinking herb tea. Historically, herb teas were used as medicine, and many people still brew and drink them today for medicinal effect. For others, herb tea is simply the beverage of choice. Brew a tasty pot from any of the following herbs. The herb’s name is followed by the parts to be used for brewing.

Angelica (Angelica archangelica): leaves

Bee balm (Monarda didyma): leaves

Catnip (Nepeta cataria): leaves and flowers

Chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile): flowers

Costmary (Tanacetum balsamita): leaves

Elderberry (Sambucus spp.): flowers

Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis): leaves

Lemon thyme (Thymus × citriodorus): leaves

Lemon verbena (Aloysia triphylla): leaves

Mints (Mentha spp.): leaves

Roses (Rosa spp.): hips and petals

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis): leaves

Sage (Salvia officinalis): leaves

Scented geraniums (Pelargonium spp.): leaves

Potpourri is a mix of flower petals and leaves used whole for decorative effect; it can be made with fresh or dried leaves and petals. Some potpourris include dried orange or lemon peel and spices such as cloves and allspice. Experiment with different combinations and see which ones you prefer. The fragrance is usually set with a fixative, such as orris root. Or simply enjoy the fragrance of your potpourri while it lasts, stirring occasionally to release more scent. When a batch of potpourri loses its color and freshness, compost it and replace with freshly made mix.

Companion Planting

Many herbs are used as companion plants for vegetables and ornamentals. The herbs may help confuse or ward off harmful insects, or they may even act as trap plants to attract harmful insects, which can then be picked off and destroyed. Companion herbs may be used to attract bees for pollination or because of a benign effect on neighboring plants. You may want to try planting your basil by your tomatoes; mint by the cabbages; and catnip, which discourages flea beetles, by the eggplant. Or try putting a few garlic plants near roses or anything else victimized by Japanese beetles.

Some plants may be detrimental to another’s growth; keep dill away from the carrots, fennel away from beans, and garlic and onions away from all legumes. As you carry out experiments in your garden, keep records for your own benefit and perhaps for that of other gardeners. See the list on page 316 and the Companion Planting entry for more suggestions about helpful and harmful plant companions.

Fragrant Herbs

Here are some of the fragrant herbs that can be used, fresh or dried, for herbal crafts such as wreaths, potpourri, sachets, or arrangements. Plant name is followed by common uses.

Aloysia triphylla (lemon verbena): highly prized for potpourri and tea

Artemisia abrotanum (southernwood): dried branches traditionally hung in closets to repel moths

Artemisia annua (sweet Annie): sweetly aromatic flowers and foliage make good filler for herbal wreaths

Chenopodium botrys (Jerusalem oak, ambrosia): fluffy gold branches good for herb wreaths

Galium odoratum (sweet woodruff): leaves especially fragrant when dried; used in potpourri, wreaths, and as a tea

Lavandula angustifolia (lavender): flowers and foliage used in many herbal crafts

Melissa officinalis (lemon balm): used in teas, food, potpourri, and commercially in soap and toilet water

Mentha spp. (mints): fragrant foliage used in teas, potpourris, wreaths, and other herbal crafts; orange mint probably best for fragrance

Monarda didyma (bee balm): blossoms and foliage used in wreaths, potpourris, and teas

Pelargonium spp. (scented geraniums): a wide variety of its fragrant leaves used in sachets and potpourris; edible flowers

Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary): fragrant, needlelike leaves used for tea, cooking, and winter sachets

Salvia elegans (pineapple sage): wonderfully fragrant leaves and scarlet flowers used in wreaths and other herbal crafts; edible flowers

Santolina chamaecyparissus (lavender cotton): used in herb wreaths; odor of gray foliage may be too medicinal for sachets or potpourri

Thymus spp. (thymes): leaves and tops used in sachets and wreaths

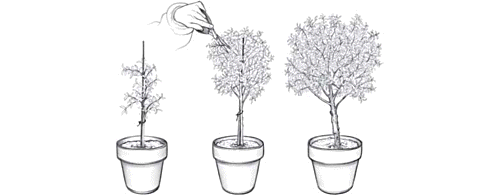

Herbs as Standards

A standard plant is one trained to a single stem, with leaves and branches only at the top. Standard roses, sometimes called tree roses, are used in formal gardens or designs. Herbs are sometimes trained as standards to serve as accents in herb gardens, particularly in formal ones. Standard herbs make charming table decorations, especially at holiday time.

A simple design of a rounded head atop a single stem is a classic. You can also create multilayered standards or train herbs into upright wreath shapes. Here’s how to train a basic herb standard:

- Insert a slim bamboo stake of the height you want your standard to attain, pushing the stake in until it touches the bottom of the pot.

- Cut back all side branches below the desired height to 1½ inches. Allow leaves that grow from the main stem to remain.

- Tie the stem to the stake with slender strips of raffia or twist-ties at 2-inch intervals.

- As new shoots appear at the top, clip the tips to encourage branching and to make a bushy head.

- When your plant reaches the desired height, pinch off the tip of the top shoot and remove all the lower leaves and branch stems to within 4 to 5 inches of the top. Shape the head with clippers to form a rounded globe.

Herbs for Repelling Insect Pests

Planting herbs as companion plants in the vegetable and flower garden is a time-honored but not infallible way of helping to deter some pests. See if your most troublesome pests are on this list, and if so, give companion planting with the appropriate herbs a try.

Allium sativum (garlic): useful against aphids, Japanese beetles

Artemisia spp. (artemisias): repel flea beetles, cabbageworms, slugs

Coriandrum sativum (coriander): discourages aphids

Lavandula spp. (lavenders): repel moths; combine with southernwood, wormwood, and rosemary in a moth-deterring sachet

Mentha spp. (mints): deter aphids, cabbage pests, flea beetles

Nepeta cataria (catnip): useful against ants, flea beetles

Ocimum spp. (basils): deter flies and other insects

Pimpinella anisum (anise): repels aphids

Rosmarinus spp. (rosemaries): repel moths; use in sachets

Satureja hortensis (summer savory): protects beans against Mexican bean beetles

Tanacetum coccineum (pyrethrum): dried flower heads can be used as insect repellent

Tanacetum parthenium (feverfew): repels many insects

Tanacetum vulgare (common tansy): discourages Japanese beetles, ants, flies; can be invasive, so best for a large container

Best Herbs for Standards

Choose herbs with a sturdy stem that can support the weight of the full, rounded head. Lemon verbena, myrtle, rosemary, scented geraniums, lavender, and sweet bay can be trained into attractive standards. The main stem will thicken with age, but standards should remain tied closely to their stakes to protect them from damage. Running children and animals or high winds can easily tip them over.

Training an herb standard. Choose a young, straight, single-stemmed plant for making an herb standard. Attach the plant to a stake and pinch new shoots at the tip as they appear. Over time, your herb plant will fill out to the form of a miniature tree.

Scented geraniums with a compact growth habit and tightly packed leaves make excellent candidates. With the small-leaved types, aim for a tight globe of foliage and pinch off the flowers. The larger-leaved ones are suitable for a less- formal effect; allow them to decorate themselves with flowers if they wish. In fact, they look splendid when blooming.

If you want a scented geranium standard to be 3 feet tall, remove all side shoots from the bottom 2 feet of stem. When the central stem has reached 3 feet, pinch the tip. As the crown burgeons, keep it trimmed to encourage branching.

HEUCHERA

Heuchera, coral bells, alumroot. Spring-to summer-blooming perennials.

Description: Heuchera micrantha and its hybrids (chiefly with H. americana and H. villosa) are noted more for their foliage than their airy sprays of small, unobtrusive flowers. Plants form showy 1- to 2-foot clumps of maple-like leaves in shades of purple, garnet, chartreuse, silver, and peach, and there are many cultivars with foliage that is variegated with contrasting veins. Some choice selections include ‘Garnet’, with brilliant red-purple autumn color; ‘Pewter Veil’, with smoky gray and purple leaves; ‘Amber Waves’, with gold and pink leaves; ‘Palace Purple’, with purple-brown foliage; ‘Peach Melba’, with peach-colored leaves; ‘Crème Brulee’, with burnt orange foliage; and ‘Key Lime Pie’, with chartreuse foliage. Zones 4-8.

Heuchera sanguinea, coral bells, and hybrid coral bells, H. ✕ brizoides, bear clouds of delicate ½-inch hanging bells in shades of white, pink, red, and green. Flowers are borne on thin, 1½-foot stems above low mounds of rounded to maplelike 2-inch evergreen leaves. Zones 3–8.

How to grow: Plant in spring. Grow in partial shade in moist but very well-drained, humus-rich soil. Plants tolerate full sun in the North if kept moist. Good drainage and loose mulch help reduce freeze-and-thaw winter damage to the fragile roots. Support weak stems with thin, twiggy branches. Divide in spring when the centers die out.

Landscape uses: Mass in open woodlands, in borders, and among rocks. Contrast with hostas, ferns, columbines, iris, bleeding hearts, or wildflowers.

HIPPEASTRUM

Amaryllis. Winter-and spring-blooming bulbs for pots.

Description: Hippeastrum hybrids, commonly called amaryllis, bear flamboyant 4- to 12-inch-wide, trumpet-shaped blooms in white, pink, red, and salmon, usually in clusters of four on leafless stems normally rising 1 to 3 feet. Cultivars may have petals that are striped, streaked, or outlined with a second color, and many newer cultivars bear double flowers. Arching fans of broad, straplike leaves appear during or after flowering. Hardy only in Zones 9–10, amaryllis plants are usually grown indoors as showstopping container plants.

How to grow: Choose a pot that will allow about 1 inch of growing space between the bulb and the rim. For a suitable soil mix, see the Houseplants entry on page 320. Plant with one-third to one-half of the bulb above the soil line. Water slightly until growth starts, then water often. Grow in a warm (65° to 70°F) spot in a sunny window, especially after the leaves develop. Most bloom 4 to 8 weeks after growth begins. Once the flowers open, moving the plant to a cool spot out of direct sun will lengthen the life of the flowers.

When the flowers fade, cut off the flower stalk close to the bulb. Return the plant to a sunny window and water regularly. You may keep the plant inside all year, feeding every 2 to 3 weeks with liquid seaweed, fish emulsion, or other organic fertilizer. You can put your amaryllis outside after danger of frost is past in a spot with morning sun or under the shade of tall trees, or knock them out of their pots and grow them in the open ground. Gradually reduce water in late summer to encourage dormancy. After a few months’ rest, replace the top few inches of soil or repot and begin again.

HOLLY

See Ilex

HOLLYHOCK

See Alcea

HONEYSUCKLE

See Lonicera

HORSERADISH

Armoracia rusticana

Brassicaceae

This pungent root crop makes a wonderful sauce for meat and fish and a great addition to mustards and other condiments, but beware—it’s a vigorous perennial that can quickly spread beyond the boundaries of its planting area.

Planting: Horseradish seldom produces seeds, so you’ll need to start plants from root cuttings in moist, rich soil. Horseradish roots can grow several feet deep; good soil preparation will encourage thick, straight roots. Plant in early spring by digging a trench and laying the root cuttings in it. Position the large end of each cutting slightly higher than the small end. Cover the roots with 6 to 8 inches of soil; space 1 foot apart in rows 3 to 4 feet apart.

To prevent your horseradish patch from becoming a weedy nuisance, either plant it in an out-of-the-way area, or dig it up completely each year and replant only a few of the roots. Another method is to plant it in a bottomless bucket that you’ve sunk into the soil.

Growing guidelines: Horseradish plants are usually problem free. Water when needed, particularly in late summer and fall, when the plants do most of their growing.

Harvesting: Pick a few spring leaves as needed for salads; use a spading fork to dig roots in October or November, after active growth has stopped. The hardy roots will keep in the ground for several months; unharvested pieces will sprout the following spring.

HORTICULTURAL THERAPY

Horticultural therapy involves the cultivation and appreciation of plants and nature to relieve an illness or disability. In a sense, all gardeners practice it when they enjoy working in the garden. People with mild to severe physical, developmental, emotional, and mental disabilities also benefit from the therapeutic effects of plants.

Horticultural therapy is practiced in such diverse settings as rehabilitation and mental health centers, nursing homes, schools, and hospitals. Many older and disabled people practice horticultural therapy in their homes. Sometimes teachers use horticultural therapy in the classroom.

Horticultural therapists make gardening accessible by creating gardens with wide, wheelchair-friendly paths, raised beds and containers for easier access, and specially adapted tools. They may choose plants based on color, fragrance, and/or texture to enhance the sensory experience of gardening.

Many universities now offer classes and degrees in horticultural therapy. The American Horticultural Therapy Association lists accredited programs on their Web site, so you can find a college or university near you offering a degree or certificate in horticultural therapy. For more information, contact the American Horticultural Therapy Association or visit their Web site (see Resources on page 672).

HOSTA

Hosta, plantain lily, funkia. Summer- and fall-blooming perennials grown primarily for their foliage.

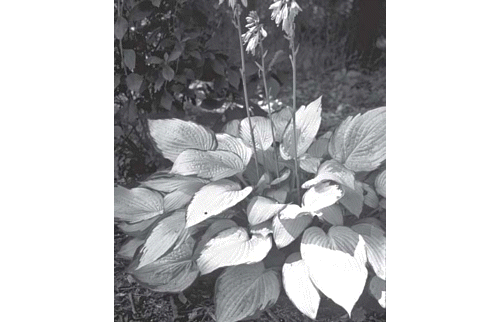

Description: Hostas display 6- to 48-inch-wide mounds of lancelike to broad, long-stemmed leaves in green, white, yellow, and bluish solid colors and variegations. Trumpet-shaped flowers, sometimes fragrant but often not very showy, are borne on stalks above the leaves. Many famous hosta cultivars, such as the huge blue-leaved ‘Krossa Regal’ and massive chartreuse-leaved ‘Sum and Substance’, are hybrids.

Hosta fortunei, Fortune’s hosta, grows into a clump, 1 to 2 feet tall and wide, of 5- to 6-inch oval leaves. Zones 3–8.

H. plantaginea, August lily, holds 6-inch, sweetly fragrant white trumpets 2 feet above bold, 8-inch, light green leaves in 2- to 3-foot-wide clumps in late summer. Zones 3–8.

H. sieboldiana, Seibold’s hosta, bears quilted bluish 1-foot leaves in 2- to 3-foot mounds up to 4 feet wide. ‘Frances Williams’, with huge gray-green leaves with wide yellow margins, is one of the most famous of all hostas. Zones 3–8.

Grow H. ventricosa, blue hosta, for its 3-inch hanging blue-violet bells on 3-foot stalks above rich green, 8-inch leaves in 2-foot-wide mounds. Zones 3–9.

How to grow: Plant or divide hostas in spring or fall. They prefer partial to deep shade and moist, well-drained soil with some organic matter. Some can take full sun in the North if kept moist. Yellow- and blue-leaved cultivars color better if given morning sun. Some older cultivars of Fortune’s hosta and blue hosta withstand very dry soil and deep shade. Slugs and snails can chew holes in emerging leaves in spring; otherwise, hostas are easy, tough plants.

Landscape uses: Grow in groups or, with showy cultivars, as specimens. Hostas cover dying bulb foliage, so they’re excellent companions for spring-looming bulbs. They lighten up dark, shady areas under trees or in corners. These shade-garden staples look gorgeous with ferns, wild gingers (Asarum spp.), hellebores, heucheras, and other shade plants.

HOUSEPLANTS

Houseplants offer beautiful foliage, brilliant flowers, and enticing fragrances to brighten your home. There are hundreds of species and thousands of cultivars you can choose from, from exotic orchids and cacti to the familiar and beloved African violet and rex begonia. You can be sure your plants will thrive if you understand their basic needs.

Starting Off Right

When you buy a new plant, it should include a label with information about its light, moisture, soil, and temperature requirements. Check this before you buy the plant—some need high humidity, strong light, or other conditions that may be difficult for you to provide. Buy plants from a reputable plant store, houseplant catalog, or Web site.

If you’re unsure what a plant is or whether it would thrive in your conditions, ask a store clerk, check out a houseplant book from the library, or do a little online research before you buy.

Choose plants that look well taken care of and vigorous. Inspect plants closely for signs of insects or disease; be sure to check the underside of the leaves and stems. If you see any insects or signs of insect feeding such as holes, punctures, or deposits of leaking sap, don’t buy. Portions of the plant that are wilted, yellowish, reddish, or brownish, have speckled leaves, or have dead areas also may indicate disease or insect damage. If you see anything suspicious, don’t buy the plant. If you do not know what the plant should look like, ask a knowledgeable salesperson.

Light Is the Key

When selecting a plant, be sure its light requirements match your proposed location. A plant that needs direct sun, like a cactus and many herbs and orchids, will slowly die in a dim corner.

Analyzing light levels: The number and position of the windows in a room and the location of a plant determine the amount of light it gets. Light intensity drops off rapidly as you move away from a window. Plants that aren’t receiving enough light often become elongated and pale. Or they may just fail to grow at all and drop their lower leaves. (A plant moved from a greenhouse into your home may also drop some leaves at first as it adjusts to the lower light levels.) Too much light, on the other hand, may burn the leaves of low-light plants like African violets and phalaenopsis (moth) orchids.

Most houses have many good locations for plants that need low light, and fewer suitable locations for plants that need moderate to bright light. Place light-loving plants as close to windows as possible; south-facing windows will provide the most light. Remove sheer curtains and keep windows clean to maximize light. Wash plants regularly to remove dust.

Rotate plants that need moderate light between a low- and a high-light location every few days. You should also rotate plants as they come into bloom, moving them to a table or other area where you can enjoy the flowers, then back to a higher-light area when bloom has passed.

Maximizing window space: To give your plants more light, add shelves or plant hangers to windows or provide plant stands to increase the amount of space you have available. If your windowsills are narrow, you can install shelf brackets under the sills and add boards to widen the windowsills. You can also install several shelves across a window and create a curtain of plants. Heavy plexiglass is good for upper shelves. Use wood screws to mount brackets to wooden window frames. To mount brackets on the wall next to the window, use appropriate wall anchors.

Adding artificial light: Plant stands with attached light fixtures are another option. There are tabletop setups with a single light or two- and three-tiered stands with multiple lights. A three-tiered plant stand is the perfect setup for a large collection of houseplants, giving them the light they need without blocking your windows or taking up table or counter space. You can adjust the height of the lights to suit plants’ needs, and use regular fluorescent lights (pairing warm and cool bulbs is best) or special full-spectrum or grow lights. Growing plants together like this also raises the humidity around the plants, especially if you put them on trays filled with pebbles and water. And it makes watering easy since the plants are all in one place.

Summering outdoors: An excellent way to increase the amount of light your plants receive is to use them to decorate your patio or garden in summer. Direct sunlight can easily burn leaves of houseplants accustomed to low light levels. Always place them in the shade at first and gradually move only those that like direct light out into sunnier locations. You may need to water smaller plants daily during hot spells, especially those in clay pots.

Watering

Various factors—including size of containers, season, rate of growth, light, and temperature—will affect how much water each plant requires. Some plants need water only when the soil surface has dried out, while others need to be kept constantly moist. You shouldn’t follow a strict schedule year-round, because you may over-water or underwater. Learn each plant’s preference, and check each pot before you water.

There are various ways of determining how much moisture is in the soil. Don’t wait until the plant wilts to water it. Looking at the surface color of the soil helps, but doesn’t tell the whole story. Learn to judge how moist the soil is by hefting the pot. Or push your finger into the soil an inch or so and feel for moistness. Avoid over-watering, which can suffocate the plant’s roots; if in doubt, wait.

Always water thoroughly, until water seeps out the bottom of the pot. Use pots with drainage holes and saucers, but never allow plants to sit in water. If the soil becomes very dry, it may shrink away from the pot sides, allowing water to run through rapidly without being absorbed. If this happens, add water slowly until the soil is saturated, or set the pot in a tub of water for a few minutes. Water will also run out rapidly if the plant is rootbound, in which case it needs repotting in fresh soil and a larger container.

Feeding

Plants growing in a rich organic potting mix containing organic matter and bonemeal need little additional fertilizer if repotted regularly. During active growth in spring and summer, most plants appreciate regular doses of a liquid organic fertilizer such as fish emulsion (if you can stand the smell—this is a better choice for houseplants summering outdoors) or liquid seaweed. Mix at half the strength recommended on the label, and apply at the recommended frequency or more often as needed. You can also find a selection of organic fertilizers designed for houseplants, including composted manure pellets and guano; use them according to package directions. Fertilize less during winter, when lower temperatures and light levels slow most plants’ growth.

Best Houseplants for Low-Light Locations

Try these low-light houseplants to brighten your home.

Aglaonema commutatum (Chinese evergreen)

Aspidistra elatior (cast-iron plant)

Chlorophytum comosum (spider plant)

Cissus antarctica (kangaroo vine)

Cissus rhombifolia (grape ivy)

Dracaena marginata (dragon tree)

Ferns (various species, including Nephrolepis exalta var. bostoniensis, Boston fern)

Philodendron spp. (philodendrons)

Saintpaulia ionantha (African violet)

Spathiphyllum wallisii (spathe flower)

Temperature and Humidity

Many popular houseplants are well suited to the warm, dry conditions found in most homes. Others, such as many ferns, will only do well if you provide extra humidity. Place a large saucer or tray filled with water and pebbles under the pot, but be sure the pot doesn’t sit in water. Mist plants often, run an electric humidifier, or group several plants together to increase humidity.

It’s important to know what temperature your plants prefer. Some plants require cool winter temperatures to either bloom or to overwinter successfully. South African plants like clivias need a cool, dry rest period to bloom. Overwintering herb plants such as rosemary and sweet bay do best with cool winter temperatures.

Organic Potting Soil

Good soil structure and fertility are maintained outside by the addition of organic matter, and by freezing, thawing, and earthworm activity—conditions that don’t occur in the soil of indoor plants. For that reason, a good organic potting mix is important for houseplants. As they grow, your plants should be repotted into fresh soil in larger containers. Use commercial organic potting soil (read the label if it doesn’t say “organic,” as it may contain synthetic chemical fertilizers and very little organic matter) or blend your own. If you have a lot of plants, you may want to make your own mix, both to save money and to provide a rich organic soil.

To prepare a good potting mix, combine: 1 to 2 parts commercial organic potting soil or good garden soil; 1 part builder’s sand or perlite; and 1 part coir fiber or peat moss, compost, or leaf mold. Add 1 tablespoon of bonemeal per quart of mix.

Gift Plants

No matter what the season, some type of seasonal gift plants are always on sale at florist shops, supermarkets, and home stores. These plants look great in the store (or catalog or on the Web site), but they’re designed to function like bouquets—enjoyable in bloom, but then disposable—rather than like houseplants. Often, to bring them back into bloom or even keep them alive requires specialized knowledge and conditions.

The best-known example of this is the poinsettia. Yes, you can bring one back into bloom, if you’re willing to keep it outdoors all growing season, then bring it back inside and give it a specialized regimen of light and dark periods until it colors up again. But few people are willing to make all this effort when a new—and probably far lusher—plant will be available the following Christmas for a few dollars.

Other popular gift plants that fall into this category are cyclamen, kalanchoes, forced bulbs, and tropical orchids. Even some plants that you’d think would thrive, such as miniature roses, azaleas, hydrangeas, and conical rosemary “trees,” are unlikely to survive dry, dark indoor conditions from Christmas, when they’re typically sold, until it’s warm enough to set them outside. That’s because they’re used to hot, bright, humid greenhouses, and the shock of home conditions causes leaf drop or disease problems. (If you’re looking for more than a temporary decoration, wait until spring and then select rosemaries and mini roses from a reputable nursery that were grown to raise in the garden.)

If you’re thinking of buying a gift plant (for yourself or someone else), consider the overall environmental cost of raising plants (usually through conventional rather than organic means) that aren’t meant to last. A “greener” alternative could be to seek out a local organic cut-flower grower or an Internet source of organic flowers, and make a gift of organically raised flowers. And remember, if someone gives you a traditional gift plant, don’t beat yourself up if it doesn’t survive long. It really isn’t your fault.

Each of these components provides specific benefits to the plants: Soil contains essential minerals. Sand and perlite assure good drainage, which prevents disease and allows air to reach the roots. Sand will make the mix much heavier. Perlite, an expanded volcanic rock with many tiny air spaces, will make it lighter. Compost or leaf mold (organic matter) makes the mix rich. Both release nutrients slowly, help maintain proper soil pH, improve soil drainage, and hold moisture. Peat moss is acidic and has few nutrients, but greatly increases the water-holding capacity of a mix. Coir fiber, made from coconut hulls, doesn’t acidify the soil and isn’t endangered, as some sources of peat moss may be, and it also retains moisture, so it’s an excellent peat replacement in soil mixes.

For plants that need extra-rich soil, double the amount of compost or leaf mold. If the plant needs acid soil, double the amount of peat moss. For cacti and succulents that like drier conditions, add an extra half to 1 part coarse sand.

You may want to add other organic amendments such as blood meal, guano, pelletized manure, rock phosphate, or greensand. See the Fertilizers entry for the specific nutrient content of each. See the Container Gardening entry for more information about adding soil amendments to potting mixtures and for blending potting mixtures to use in large pots.

Repotting