PACHYSANDRA

Pachysandra, spurge. Evergreen perennial groundcovers.

Description: Pachysandra terminalis, Japanese pachysandra or Japanese spurge, has oval, glossy, dark green, 1-to 3-inch leaves set in whorls 6 to 8 inches high. Plants have underground creeping stems that spread steadily, producing a thick carpet. In May, white flower clusters appear on stout, fuzzy spikes. Japanese pachysandra has been identified as an invasive species in some areas. Zones 4–9.

P. procumbens, Allegheny spurge, is native to the Southeast. Leaves are coarsely toothed at the ends and mottled with purple. Flowers are white and borne near the ground. Plants are evergreen in the South, semi-evergreen to deciduous in the North, and are a handsome native ground-cover. Zones 5–9.

How to grow: Pachysandras prefer partial shade in rich, moist, slightly acid soil. The plants can adjust to deep shade, but the leaves yellow in full sun. In fall, top-dress the soil with dehydrated manure, or mulch lightly with compost. Rejuvenate old plantings by mowing in spring. Propagate in spring by division or cuttings. Space plants 6 to 12 inches apart.

Landscape uses: Plant pachysandras under shallow-rooted trees or broad-leaved evergreens. Pachysandras are excellent groundcovers for banks, slopes, or any difficult shaded areas. Keep Japanese pachysandra away from wooded areas or other sites where it may spread beyond the garden, because it can compete with populations of native wildflowers.

PAEONIA

Peony. Spring-blooming perennials.

Description: Cultivars of Paeonia lactiflora, common garden or Chinese peony, bear 3-to 8-inch single to double blooms in white, pink, and red shades, many with tufted (and sometimes yellow) centers. Common garden peonies bloom over a 4- to 6-week season above elegant, 4- to 10-inch, glossy, dark green leaves on shrublike plants averaging 3 feet tall and wide. The foliage remains attractive throughout the growing season, often flushing red, purple, or bronze in fall. Two famous fragrant cultivars that have stood the test of time are ‘Festiva Maxima’, a double white flecked with red, and ‘Sarah Bernhardt’, a soft pink double. Zones 2–8. P. officinalis, common peony, bears 4- to 5-inch satiny, vivid purplish red blooms on 1½- to 2-foot mounds of medium green, matte foliage resembling the common garden peony’s. It blooms about a week before the common garden peony. Zones 3–8.

Tree peonies are derived from several species, including P. suffruticosa, P. lutea, and P. delavayi. Unlike herbaceous peonies, tree peonies have woody stems that don’t die back to the ground in winter. The single, semidouble, or double flowers may be up to 10 inches across and come in white, pink, red, salmon, deep purple, yellow, and apricot. The sometimes-fragrant blooms appear in mid-spring on sturdy, well-branched, 4- to 6-foot shrubs with divided dark green leaves. The plants are slow growing, but they can live for decades with a little extra care once established. Zones 3–8; provide winter protection in Zones 3–5.

How to grow: Plant peonies during late summer in the North or early fall in the South. If you wish to increase a favorite plant, divide herbaceous peonies at the same time. (Expect at least a year for the plant to settle in before blooming again.) Peonies prefer a sunny spot (partial shade in the South and for pastel cultivars) with fertile, well-drained soil. They can remain in the same spot for many years, so prepare a roomy planting hole with lots of compost.

Improper planting is a common reason for failure to bloom. For herbaceous peonies, make sure the tips of the pointed, pinkish new shoots, called eyes, are just 1 to 2 inches below the surface of the garden bed. Plant tree peonies with the graft union about 6 inches below the soil surface.

Remove foliage of herbaceous peonies when it dies down after frost. Tree peonies benefit from a light yearly pruning to promote bushy growth; also, remove all suckers from the rootstock. Both kinds of peonies benefit from a layer of mulch the first winter or two after planting. In early spring, feed plants with a balanced organic fertilizer; keep soil evenly moist throughout the growing season. Peonies often flop over from the sheer weight of the blooms or from a heavy rain; to prevent this, use a plant hoop to keep the stems upright, pushing it into the ground as growth emerges in spring. Single-flowered peonies are less likely to flop than those with heavier blooms.

Botrytis blight can cause wilted, blackened leaves and make buds shrivel before opening. Remove wilted parts immediately. Cut stems to ground level after frost blackens leaves. Anthracnose appears as sunken lesions with pink blisters on stems. Pruning off infected areas and thinning stems to improve air circulation will help lessen anthracnose problems. Infection by root knot nematodes can cause plants to wilt, become stunted, and have yellowed or bronzed foliage. Roots may be poorly developed and have tiny galls on them. Dig out and destroy severely infected plants.

Landscape uses: Use as specimens or in small groups in borders. Grow peonies alone in beds or in dramatic sweeps along a lawn, foundation, wall, walk, or driveway, or around a focal point such as a fountain or statue.

PALMS

Palms. Evergreen trees or shrubs.

Description: Approximately 4,000 species of palms are found in the world’s tropical and subtropical regions; palm fruits, oils, and building materials make the palms an economically important family. Eight or nine genera of palms are native to the United States, where they occur mostly in the Southern coastal regions. For palm resources, visit the Web site of Jungle Music Palms & Cycads or the International Palm Society; see Resources on page 672.

Cycas revoluta, Japanese sago palm or simply sago palm, is not a true palm, but is included with palms for practical purposes. It consists of a rosette of stiff, coarse, compound leaves that are a dull dark green and 2 to 7 feet long. Japanese sago palm may develop a trunk after many years but will stay within the range of 3 to 5 feet tall. The plant bears a conelike male flower and a female flower that may eventually bear fruit. Zones 8–11.

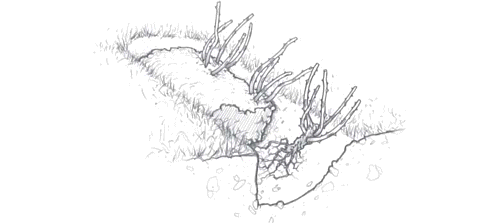

Raphidophyllum histrix, needle palm (also called porcupine palm, hedgehog palm, and blue palmetto), forms a low rounded clump with a coarse outline. The 3- to 4-foot-long foliage is blue-green and fanlike, with black needlelike sheaths protruding at the bases of leaves. This palm is hardier than most, tolerating temperatures down to 0°F. Zones 7–11.

Sabal palmetto, cabbage palmetto (also called Carolina palmetto), is a Southeast coastal native that can survive temperatures of 10° to 20°F in its home habitat. Cabbage palmettos reach 80 to 90 feet tall and bear fan-shaped leaves that are 5 to 6 feet long, 7 to 8 feet wide, and deeply divided. Cabbage palmetto is the state tree of both South Carolina (it is featured prominently on the South Carolina state quarter) and Florida. Zones 8–11.

Sabal minor, dwarf palmetto, forms a mounding, coarse-textured rosette of stiff, fanlike, compound leaves growing 3 to 8 feet long. Small whitish flowers appear on stalks in summer, followed by black fruits in autumn. Often found growing in the shade of taller trees, dwarf palmetto grows 3 to 5 feet tall. Zones 8–11.

Serenoa repens, saw palmetto, is similar to dwarf palmetto in many ways. It has olive to blue-green, fan-shaped foliage with coarse serrations along the edges. Large branches (up to 3 feet) of small, fragrant white blossoms appear in summer and are favorites of bees. Berrylike, bluish black fruits provide food for wildlife. Saw palmetto spreads via rhizomes, making it difficult to transplant or remove. Zones 8–11.

Trachycarpus fortunei, windmill palm or Chinese fan palm, has an erect form with a slender trunk and a head of large, fan-shaped leaves of dull dark green. The texture is coarse and bristly from the stiff crown to the fiber-covered trunk. Look for yellow flowers among the foliage and bluish fruits developing afterward. At heights of 15 to 30 feet, windmill palm is a good choice for small spaces, such as courtyards and entryways. It’s also more cold tolerant than most palms, surviving temperatures down to 5°F. Zones 7–11.

Washingtonia filifera, petticoat palm or California fan palm, is a West Coast native that lines streets in southern California and Florida. Petticoat palm, so-named because its persistent foliage hangs down from the crown to form a “petticoat” around the trunk, grows to 50 feet tall in the landscape; fan-shaped gray-green leaves may be 6 feet wide on mature plants. Zones 9–11.

How to grow: Most palms require full sun and fertile, moist, slightly acid soil. Dwarf palmetto is somewhat shade tolerant and often lives beneath a hardwood canopy; cabbage palmetto will also tolerate partial shade. Fertilize lightly in spring and summer. Palms are extremely susceptible to cold injury, so don’t do anything (like heavy or late fertilization) that would cause plants to produce tender new growth in fall. Cold injury is most damaging when it affects the palm’s crown, from which all new growth arises; plants that suffer damage to leaves may look unhealthy but will survive.

Landscape uses: Use low-growing palms for naturalizing, groundcovers, barriers, massed plantings, or foundation plants. Don’t plant sharp-leaved saw palmetto or needle palm in high-traffic or play areas, but consider either for a durable hedge. Use windmill and petticoat palms as focal points. Petticoat palms and cabbage palmettos are good street trees in California and Florida. Beyond the coastlines of the Southeast and Southwest, even hardy palms are limited to container growing in the United States.

PAPAVER

Poppy. Spring-to summer-blooming annuals, biennials, and perennials.

Description: Poppies bear saucer-to bowl-shaped blooms with prominent central knobs. Single, semidouble, and double poppies bloom on long stems above masses of hairy leaves; flower colors include solid shades and combinations of white, pink, red, purple, yellow, and orange. The delightful state flower of California, the annual or tender perennial California poppy, is in an entirely different genus (though also in the poppy family); its botanical name is Eschscholzia californica.

Annual Papaver rhoeas, corn poppy or Flanders poppy, produces 2-inch red blooms on sparse-leaved plants usually reaching 2 feet.

Biennial or short-lived perennial P. nudicaule, Iceland poppy, bears 2- to 6-inch, mostly single, orange, salmon, pink, or white blooms over basal rosettes of gray-green leaves; plants reach 1 to 1½ feet tall. Zones 2–7.

Perennial P. orientale, Oriental poppy, offers dazzling 6- to 10-inch-wide red, scarlet, white, pink, or purple flowers (most with striking black blotches inside) on stems from 2½ to 4 feet above dense, leafy masses. Zones 2–7.

How to grow: All poppies are easy to grow and prefer full sun to very light shade and average to rich, moist but well-drained soil. Direct-sow corn poppies in spring; start Iceland poppies in late summer in the North (fall in the South) for bloom the next year. Allow both to self-sow. Plant container-grown Oriental poppies in spring or in summer after the leaves disappear, which is an ideal time to divide them if necessary. Give Oriental poppies plenty of room in the bed or border—mature plants can take up as much as 3 feet of bed space. Provide light, loose mulch in winter.

Landscape uses: Grow in borders and informal gardens, or enjoy a solid bed or mass of corn or Iceland poppies. Combine Oriental poppies with later-blooming annuals and perennials like asters to fill the large gaps when the poppies go dormant, but leave room for leaves that reemerge in fall. Flowers last a few days in water if cut ends are seared in a flame.

PARSLEY

Petroselinum crispum

Apiaceae

Description: Parsley is a decorative 8- to 18-inch biennial with much-divided leaves. In its second year, it produces small yellow flowers in flat umbels. To some, the leaves have a bitter taste and smell of camphor; most people, however, enjoy the pleasantly pungent flavor.

There are two distinct kinds of parsley available—curly and flat-leaved. Flat-leaved or Italian parsley (Petroselinum crispum var. neapolitanum) has luxuriant, shiny leaves and contains more vitamin C than the curly kind. It also has superior flavor. Curly parsley (P. crispum var. crispum) has ruffled leaves; it is popular in cooking and as a garnish. All parsley contains three times as much vitamin C, weight for weight, as oranges. It is also a fine source of vitamin A and iron. Both types will grow in Zones 3–9, though in zones colder than Zone 5, parsley should be treated as an annual.

How to grow: You can plant parsley outdoors in spring, but since it is slow to germinate (4 to 6 weeks), it’s better to start seeds indoors. In either case, first soak the seeds in warm water for several hours or overnight.

For a reliable supply, sow new parsley plants each year. Although it’s hardy, parsley will flower and die the second year unless you remove the flower stalks. Parsley plants that do flower in the garden will often self-sow. Pot up small plants in fall for indoor use.

Harvesting: Pick leaves as you need them. Freeze chopped or whole parsley in self-sealing bags to keep more of its fresh flavor, or dry them on screens in a food dehydrator or in an oven or microwave.

Uses: You can use parsley to enhance salads as well as main and side dishes, since its flavor combines well with most other culinary herbs and nearly all foods except sweets. It is traditionally one of the French fines herbes used in soups, omelets, and potato dishes; it’s delicious in soups, stews, and pasta sauces; and it is indispensable in Middle Eastern dishes like tabbouleh.

PARSNIP

Pastinaca sativa

Apiaceae

Parsnips are large carrot-shaped roots with a distinctive nutty-sweet taste. They require 100 to 120 days to mature and need a bit of extra soil preparation, but parsnip lovers know they’re worth the effort. Prepare parsnips like carrots—steamed or sliced into soups or stews. For an extra-special treat, try roasted parsnips.

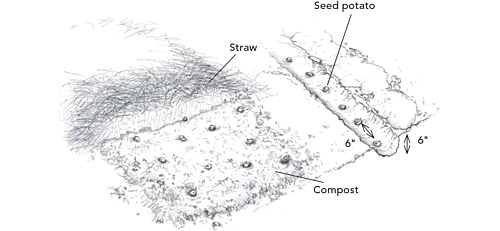

Planting: Parsnip’s cream-colored root grows 8 to 24 inches long, with 2- to 4-inch-wide shoulders. Take extra care in preparing the planting area. Loosen the soil to a depth of 2 feet; remove rocks or clods. Dig in 2 to 3 inches of compost; avoid high-nitrogen materials that can cause forked roots.

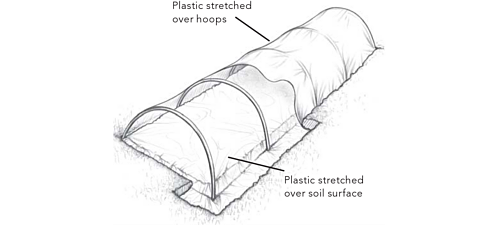

In most areas, sow seed ½ to 1 inch deep in spring or early summer. Your goal is for the crop to mature at about the time of your first fall frost. In the South, plant parsnips in fall for a spring harvest. Use only fresh seeds, and soak them for several hours to encourage germination. Even then, germination will be slow and uneven, so sow the seed thickly and mark the rows with a quick-maturing radish crop. Cover the seed with a light material such as vermiculite or fine compost and water gently; keep the soil evenly moist.

Growing guidelines: Keep young plants free of weeds, and use a light mulch to conserve moisture. Parsnips have long roots and tolerate dry conditions, but your crop will be more successful if watered regularly.

Problems: Parsnips are usually problem free. See the Carrot entry for details on controlling problems that do occur.

Harvesting: Harvest roots after a hard frost for the best flavor. Dig and store like carrots, or mulch with a thick layer of hay and leave in the ground over winter, harvesting as needed. Pull the entire crop in early spring before new growth spoils its flavor.

PEA

Pisum sativum

Fabaceae

The crisp texture and sweet taste of fresh peas embodies spring. Ancient peoples foraged for peas in the wild long before they were domesticated. Romans, however, believed fresh green peas were poisonous and had to be dried before they could be eaten. It wasn’t until the time of King Louis XIV of France that a French gardener developed a green-pea hybrid known as petits pois. Fresh peas soon became the rage at the king’s court and thereby quickly gained widespread popularity.

Types: Still a garden favorite, peas are one of the first vegetables that you’ll plant and harvest in spring. There are extra-early, early, mid-season, and late types, taking 7 to 10 weeks to mature. Vining peas need trellises to grow on, while dwarf types need little or no support. Vining peas usually produce a heavier crop than do dwarfs.

Among green—or English—peas, there are wrinkled-seeded types and smooth-seeded types, both of which must be shelled. While wrinkled green peas are sweeter, smooth ones are hardier and better for super-early spring planting and for autumn and winter crops. If you’ve had problems with pea diseases, look for disease-resistant varieties such as ‘Maestro’. If you want to can or freeze peas, choose a variety such as ‘Dakota’ that has a heavy and concentrated pod-setting period.

Snow peas and snap peas have edible pods. Snow peas produce flat pods that you can eat either raw or cooked. Snap peas are eaten either as young flat pods or after the peas have grown and are fat and juicy in the pods. Snow and snap peas are available in both vining and dwarf versions. New varieties of dwarf snow peas such as ‘Snow Sweet’ have pods that stay tender longer than traditional snow peas.

Some edible-podded cultivars have strings running down each pod that you must remove before eating; fortunately, “stringless” cultivars such as ‘Sugar Spring’ have been developed that eliminate this task. Edible-podded peas are perfect for stir-fries and other Oriental dishes.

Field peas or cowpeas—which include black-eyed peas, crowder peas, and cream peas—are, botanically, beans. These plants thrive in areas with long, hot summers. See the Bean entry for information on cultivating these crops.

Planting: Give early peas a sunny spot protected from high winds. Later crops may appreciate partial shade. You can also plant peas in mid to late summer for a fall crop. If possible, sow your fall crop in a spot where tall crops such as corn or pole beans will shade the young plants until the weather cools.

Early peas in particular like raised beds or a sandy loam soil that warms up quickly. Heavier soils, on the other hand, can provide cooler conditions for a late pea crop, but you’ll need to loosen the ground before planting by working in some organic matter. Being legumes, peas supply their own nitrogen, so go easy on fertilizer. Too much nitrogen produces lush foliage but few peas.

Peas don’t transplant well and are very hardy, so there’s no reason to start them indoors. Pea plants can survive frosts but won’t tolerate temperatures over 75°F. In fact, production slows down drastically at 70°F.

Southern gardeners often sow peas in mid to late fall so the seeds will lie dormant through winter and sprout as early as possible for spring harvest. On the West Coast and in Gulf states, you can grow peas as a winter crop. Elsewhere, if the spring growing season is relatively long and cool, plant your peas 4 to 6 weeks before the last frost, when the soil is at least 40°F. For a long harvest season, sow early, mid-season, and late cultivars at the same time, or make successive sowings of one kind at 10-day to 2-week intervals until the middle of May.

When planting peas in an area where legumes haven’t grown before, it may help to treat seeds with an inoculant powder of bacteria, called Rhizobia. This treatment promotes the formation of root nodules, which contain beneficial bacteria that convert the nitrogen in the air into a form usable by plants. To use an inoculant, roll wet seeds in the powder immediately before planting.

Space seeds of bush, or dwarf, peas 1 inch apart in rows 2 feet apart. Bush peas are also good for growing in beds. Sow the seeds of early crops 2 inches deep in light soil or 1 inch deep in heavy soil; make later plantings an inch or two deeper. Thin to 2 to 3 inches apart. This close spacing will allow bush peas to entwine and prop each other up.

Plant vining types in double rows 6 to 8 inches apart on either side of 5- to 6-feet-tall supports made of wire or string, with 3 feet between each double row. The more simple the support, the easier it is to remove the vines at the end of the pea season and reuse it.

Generally speaking, 1 pound of seeds will plant a 100-foot row and should produce around 1 bushel of green peas or 2 bushels of edible pods. Another rough guideline is to raise 40 plants per person. Unused seed is good for 3 years.

To make good use of garden space, interplant peas with radishes, spinach, lettuce, or other early greens. Cucumbers and potatoes are good companion plants, but peas don’t do well when planted near garlic or onions.

Growing guidelines: Providing peas with just the right amount of water is a little tricky. They should never be so waterlogged that the seeds and plants rot, and too much water before the plants flower will reduce yields. On the other hand, don’t let the soil dry out when peas are germinating or blooming or when the pods are swelling. Once the plants are up, they only need about ½ inch of water every week until they start to bloom; at that time, increase their water supply to 1 inch a week until the pods fill out.

Peas growing in good soil need no additional fertilizer. If your soil is not very fertile, you may want to side-dress with compost when the seedlings are about 6 inches tall.

The vines are delicate, so handle them as little as possible. Gently hand pull any weeds near the plants to keep from damaging the pea roots. To reduce weeds and conserve moisture, lay 2 inches of organic mulch once the weather and soil warms. This also helps to keep the roots cool. Soil that becomes too warm can result in peas not setting fruit or can prevent already-formed pods from filling out. Mulch fall crops as soon as they are planted, and add another layer of mulch when the seedlings are 1 to 2 inches tall.

Once a vine quits producing, cut it off at ground level, leaving the nitrogen-rich root nodules in the ground to aid the growth of a following crop, such as brassicas, carrots, beets, or beans. Add the vines to your compost pile, unless they show obvious signs of disease or pest problems.

Problems: Aphids often attack developing vines. For information on controlling these pests, see page 458.

Pea weevils can chew on foliage, especially along the edges of young leaves. They are serious only when they attack young seedlings. Apply Beauveria bassiana as soon as damage is spotted to head off problems.

Thrips—very tiny black or dark brown insects—often hide on the undersides of leaves in dry weather. They cause distorted leaves that eventually die; thrips also spread disease. Control them with an insecticidal soap spray.

See the Animal Pests entry for information on protecting seeds and seedlings from birds.

Crop rotation is one of the best ways to prevent diseases. To avoid persistent problems, don’t grow peas in the same spot more than once every 5 years.

Plant resistant cultivars to avoid Fusarium wilt, which turns plants yellow, then brown, and causes them to shrivel and die.

Root-rot fungi cause water-soaked areas or brown lesions to appear on lower stems and roots of pea plants. Cool, wet, poorly drained soil favors development of rots. To avoid root rot, start seeds indoors in peat pots and wait until the soil is frostless before setting out the plants. Provide good fertility and drainage for strong, rapid growth.

Warm weather brings on powdery mildew, which covers a plant with a downy, white fungal coating that sucks nutrients out of the leaves. Bicarbonate sprays can help to prevent mildew. Destroy seriously affected vines, or place them in sealed containers for disposal with household trash. Avoid powdery mildew by planting resistant cultivars.

Control mosaic virus, which yellows and stunts plants, by getting rid of the aphids that spread it.

Harvesting: Pods are ready to pick about 3 weeks after a plant blossoms, but check frequently to avoid harvesting too late. You should harvest the peas daily to catch them at their prime and to encourage vines to keep producing. If allowed to become ripe and hard, peas lose much of their flavor. Also, their taste and texture are much better if you prepare and eat them immediately after harvesting; the sugar in peas turns to starch within a few hours after picking.

Pick shell and snap peas when they are plump and bright green. Snow-pea pods should be almost flat and barely showing their developing seeds. Cut the pods from the vines with scissors; pulling them off can uproot the vine or shock it into nonproduction.

Preserve any surplus as soon as possible by canning or, preferably, by freezing, which retains that fresh-from-the-garden flavor. To freeze peas, just shell and blanch for 1½ minutes, then cool, drain, pack, and freeze. Snow peas, which are frozen whole, are treated the same way, but don’t forget to string them first if necessary. Peas have a freezer life of about 1 year.

If peas become overripe, shell them and spread them on a flat surface for 3 weeks or until completely dry. Store in airtight containers and use as you would any dried bean.

PEACH

Prunus persica

Rosaceae

There may be no greater pleasure than biting into a peach fresh from the tree. Growing peaches organically can be a challenge, and you’ll need to be content with less-than-perfect fruit. However, the taste will more than make up for any surface imperfection!

These wonderful fuzzy fruits are the same species as nectarines. Only a single gene controls whether a cultivar bears smooth-or fuzzy-skinned fruit.

The Fruit Trees entry covers many important aspects of growing peaches and other tree fruits; refer to it for more information on planting, pruning, and care.

Selecting trees: Most peach trees are self-fertile. One tree will set a good crop.

Select cultivars to match your climate, or see the explanation of chill hours at right for a more exact way to determine which cultivars to plant. Choose disease-resistant peaches when available.

What you plan to do with your harvest will influence your selection. Freestone fruit are easy to separate from the pit and great for fresh eating, but the melting flesh often turns soft when canned. Clingstone fruit hang onto the pit for dear life, but their firm, aromatic flesh is great for cooking and preserving.

Yellow flesh is standard, but white-fleshed peaches are quite tender and equally tasty.

If you have the space for several trees, pick cultivars that will give you a succession of harvests. Just be sure your growing season is long enough for the fruit to mature.

Rootstocks: Peach trees are sold as grafted trees; common rootstocks include ‘Lovell’, ‘Hal-ford’, and ‘Guardian’. ‘Citation’ is a dwarfing rootstock. Where nematodes are severe, try ‘Nemaguard’ rootstock. ‘Siberian C’ rootstock may be a good choice for cold climates where winter temperatures do not fluctuate. If you have warm spells, seedling rootstocks may be less likely to break dormancy prematurely. If you’re planting peach trees for the first time, ask your local extension service for recommendations of the best rootstocks for your region.

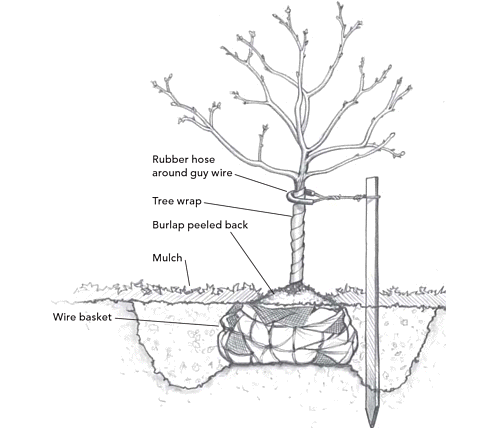

Planting: Peaches prefer soil that is well drained and sandy-light on the surface with heavier texture in the subsoil. This keeps the crown and roots dry, helping to prevent disease problems, but still provides a deep reservoir of moisture and nutrients. For best results in any soil, add organic matter and correct any drainage problems before planting. Peaches need a pH of 6.0 to 6.5. Don’t add lime if the pH is 6.2 or higher, since a high level of calcium in the soil reduces absorption of potassium and magnesium by tree roots. Fertilize with compost. Space standard peaches 15 to 20 feet apart, and space dwarfs 12 feet apart.

Peach blossoms are easily damaged by frost. In areas where late-spring frosts are common, avoid planting in frost pockets (see page 242). Instead, choose a site on the upper half of a north-facing slope. A north-facing slope warms slowly, which may delay flowering by as much as 1 to 2 weeks. Planting about 15 feet away from the north side of a building may have the same effect. A thick mulch under the trees will help delay flowering by keeping the soil cool.

CHILL HOURS

Like other tree fruits, peach trees need a period of cold-weather rest or dormancy. The number of hours of cold between 32°F and 45°F needed before a tree breaks dormancy is referred to as chill hours. (Cold below 32°F doesn’t count toward meeting the dormancy require-ment.) Once the number is reached, the tree assumes winter is over, and it starts growing the next warm day. Peaches bloom rapidly once their requirement has been met, which makes them more prone to frost damage than other tree fruits that are slower to burst into bloom.

Call your local extension service to find out how many chill hours your area receives and what cultivars match that requirement. If you choose a cultivar that needs fewer chill hours than you normally receive, it will flower too early and be prone to bud damage. But if you choose one that needs more chill hours, it won’t get enough chilling to stimulate normal bloom.

Peaches ripen best when the sun shines and temperatures hover at about 75°F. If temperatures are consistently cooler, the fruit can develop an astringent flavor or be almost tasteless. Plant your tree in a sheltered location that conserves heat to help the fruit ripen.

Since most peach trees have a maximum productive life of about 12 years, plant replacements periodically. If you plan ahead, you will always have mature trees and fresh fruit. Don’t replant in the same location, though. Viruses and nematodes, which will shorten the life of new trees, may have built up in the soil.

Care: Healthy peaches should grow 1 to 1½ feet a year. If growth is slower or the foliage is a light yellow-green or reddish purple, have the leaves and soil tested for nutrient content, and correct deficiencies. The Soil entry gives specifics on soil testing. In cold climates, fertilize only in early spring so wood can be fully hardened before winter. Mulch with compost or other low-nitrogen organic materials to maximize water and nutrient availability.

Peach trees need even moisture around their roots to produce juicy, succulent fruit. If the weather is dry or the soil is sandy, install drip irrigation over the entire root system out to the drip line. Keep the soil moist, not wet. Mulch to reduce evaporation. See the Drip Irrigation entry for more information.

Sometimes peaches flower when the weather is still too cool for much insect activity. To ensure fruit set, you must take the place of insects and spread pollen from flower to flower. Use a soft brush to dab pollen from one flower onto its neighbor. Hand pollinate newly opened flowers every day, and you’ll have a decent crop.

Frost protection: Winter temperatures of –10°F or lower will kill some or all of the flower buds of most peach cultivars. Some may even suffer cold damage to the wood, branch crotches, or trunk. The closer the cold snap comes to spring flowering time, the more severe the damage will be. Plant cold-tolerant cultivars to minimize losses. Or try letting the tree grow taller than you normally would; the upper boughs may escape frost damage.

If frost is predicted, spray an anti-transpirant the day before for 2° to 3°F of extra protection. Or get up and hose down trees with water just before sunrise.

Pruning: Train peaches to the open center system. This makes an attractive, productive tree that is low and spreading and easy to reach. For instructions, see page 246.

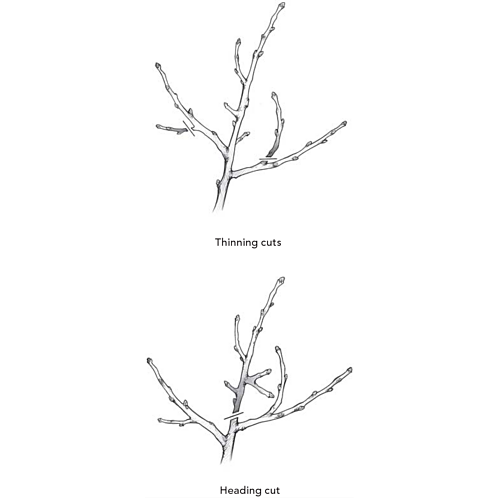

Start training your tree when you plant it. The first few years, prune as needed to shape the tree. After that, prune only to keep the tree fruiting and reasonably small. Prune each year just before the tree breaks dormancy. If canker is a problem or spring frosts are common, prune after flowering to minimize disease problems and ensure that you will have a good crop. Dry weather at pruning discourages canker invasion, and you will be able to prune more or less depending on how many buds survived winter. Heading back new growth now reduces the fruit load and your later thinning chores.

Try central leader training if your trees suffer sunscald, or protect trees by painting the larger branches with diluted white latex paint. In very cool climates, try training your peach tree against a stone or brick wall that reflects sun and radiates heat. For training instructions, see page 245.

No matter what training method you choose, try to minimize the amount of wood you remove the first few years. Rub off unwanted shoots and suckers as soon as they appear during the growing season. Your tree will bear earlier and more heavily if you do.

As the tree gets older, continue to prune each spring for maintenance and renewal. Peaches fruit only on one-year-old-wood. Encourage new growth by cutting off old branches that are no longer productive. Head back new growth by ⅓ to ½ of its length to keep the tree compact. Cut back to just above an outward-facing branch or bud. Heading back also encourages more small side branches, which are the best fruit producers, and keeps the tree from overbearing.

Thinning: Once your tree starts bearing, it may set more fruit than it can handle. Remove some of the green fruit before the pits harden, so the remaining fruit will grow large and sweet and the tree won’t break under the weight of the ripe fruit. Leave one peach every 4 to 6 inches. If you don’t remove enough, prop up heavily laden branches with a forked stick until harvest. Prune and thin harder the next year.

Harvesting: Peach trees bear within 3 years. As peaches ripen, the skin color changes from green to yellow; the flesh slightly gives to the touch when ripe. Hold the fruit gently in your palm and twist it off the branch. Avoid bruising it. You can store ripe peaches for about a week in a refrigerator.

Problems: Peach trees can be plagued by various pests and diseases; the most serious are canker and peach tree borers. Nectarine fruits are even more likely to be attacked by fruit pests than peaches are, perhaps because pests dislike the fuzzy skin on peaches.

Common peach pests include green fruit-worms, two types of peach tree borers, mites, and plum curculios. For descriptions and control methods see page 249. Aphids, Japanese beetles, scale, and tarnished plant bugs can also cause problems; see page 458 for descriptions and controls.

Oriental fruit moths lay eggs on shoots and the larvae bore into the tissue early in the season. Later generations of larvae burrow to the center of fruits to feed. Young fruits exude a gummy substance and often drop prematurely. Control this pest by removing infested shoots and fruit and destroying them. Encourage native parasitic wasps that attack the eggs and larvae.

Fall webworms and tent caterpillars spin webs and munch on leaves. Gypsy moth caterpillars also eat leaves. Destroy webs and caterpillars as soon as you see them. Spray Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) where they are feeding.

Trees infected by root knot nematodes may have weak growth and yellow leaves. Affected trees won’t bear fruit and will eventually die. If you suspect a nematode problem, ask your local extension office about having your soil tested for nematodes. To avoid nematode problems, don’t replant where peaches have grown previously, solarize soil before planting, and enrich soil with organic matter to encourage natural fungi or apply parasitic nematodes to soil before planting. ‘Nemaguard’ rootstock is resistant to root knot nematode.

Some common diseases of peaches are bacterial leaf spot, brown rot, and perennial canker (also known as valsa and cytospora). See page 249 for descriptions and controls.

Peach leaf curl is a fungal disease that causes leaves to become thick, puckered, and reddish. It’s a common problem in cool, humid areas. Symptoms appear about a month after bloom. Leaves drop soon after. Fruit will look distorted and off color. To prevent peach leaf curl, remove infected leaves and destroy them. Increase air circulation by pruning trees every year when they are dormant. It’s rare for peach leaf curl to become a serious problem, but if it’s threatening to kill off your trees, spray with Bordeaux mix (a blend of copper sulfate and hydrated lime) in fall after leaves drop or in early spring while the trees are still dormant.

Peach scab causes small, olive green spots, usually clustered near the stem end of half-grown fruit about a month after infection. Later the spots turn brown and velvety, and the skin cracks. Twigs and leaves also get peach scab. Remove and destroy infected fruit and clean up fallen leaves and fruit. Weather that is warm and either wet or humid encourages scab. Control as you do brown rot. If you’ve had problems with scab in previous seasons, spray sulfur weekly from the time the first green shows in the buds until the weather becomes dry.

Certain cankers cause wilting or yellowing of new shoots or leaves and can also girdle limbs. Delay routine pruning until after bud break to reduce the chance of infection by canker organisms. Prune out and destroy any gummy cankers on trees whenever you spot them.

Crown gall and crown rot sometimes attack peach trees; providing good drainage helps to avoid these problems. Use a sharp knife to remove galls that form near the soil line.

Virus diseases such as yellows and mosaic may cause leaf distortion, discoloration, and mottling. Buy only certified disease-free stock. Destroy infected trees immediately.

PEANUT

Arachis hypogaea

Fabaceae

Contrary to popular belief, the peanut is not a nut; it is actually a vegetable belonging to the legume family, which includes peas and beans. These tropical natives of South America require about 120 days to mature, but fortunately they can withstand light spring and fall frosts. ‘Jumbo Virginia’ is a productive variety for home gardens. Although peanuts are generally considered a Southern crop, Northern gardeners can also grow them successfully if they choose early cultivars such as ‘Early Spanish’ and start plants indoors.

Planting: Peanuts need full sun. If you have heavy soil, ensure good drainage by working in enough organic matter to make it loose and friable.

Peanut seeds come in their shells and can be planted hulled or unhulled. If you do shell them, don’t remove the thin, pinkish brown seed coverings, or the seed won’t germinate.

Northern growers should start plants indoors in large peat pots a month before the last frost. Sow seeds 1 inch deep, place in the sunniest spot possible, and water weekly. Transplant seedlings to the garden when the soil warms to between 60° and 70°F. Space transplants 10 inches apart, being careful not to damage or bury the crown.

In the South, plant outdoors around the date of the last expected frost. Space seeds 2 inches deep and 5 inches apart in rows 2 to 3 feet apart. Firm the soil and water well. Thin plants to 10 inches apart.

Growing guidelines: When the plants are about 1 foot tall, hill the earth around the base of each plant. Long, pointed pegs (also called peduncles) grow from faded flowers and then push 1 to 3 inches down into the soil beside the plant. A peanut will form on the end of each peg. Lay down a light mulch, such as straw or grass clippings, to prevent the soil surface from crusting so that the pegs will have no difficulty penetrating the soil.

One inch of water a week is plenty for peanuts. Being legumes, peanuts supply their own nitrogen, so avoid nitrogen-rich fertilizers, which encourage foliage rather than fruits. Well-prepared soil will provide all the nutrients the plants need.

Problems: Peanuts are usually problem free. For aphid controls, see page 458.

Harvesting: The crop is ready to harvest when leaves turn yellow and the peanuts’ inner shells have gold-marked veins, which you can check periodically by pulling out a few nuts from the soil and shelling them. If you wait too long, the pegs will become brittle, and the pods will break off in the ground, making harvesting more difficult. Pull or dig the plants and roots when the soil is moist. Shake off the excess soil, and let plants dry in an airy place until the leaves become crumbly; then remove the pods. Unshelled peanuts, stored in airtight containers, can keep for up to a year.

PEAR

Pyrus communis and its hybrids

Rosaceae

With their glossy leaves and white blossoms, pear trees are a beautiful accent in a home landscape. Plus they produce bushels of delicious fruit, are long-lived, and suffer fewer insect and disease problems than many tree fruits.

Most gardeners are familiar with European pears, including the familiar ‘Bartlett’ and ‘Bosc’ pears. However, Asian pears, which have crisp, juicy, almost round fruits, will also grow well in most parts of the United States and Canada. The Fruit Trees entry covers many important aspects of growing pears and other tree fruits; refer to it for additional information on planting, pruning, and care.

Selecting trees: Pears need cross-pollination to set a good crop. Most European and Asian cultivars pollinate each other. A few cultivars don’t product viable pollen; if you select one, you’ll need to plant three different cultivars to ensure good fruit set. Certain cultivars will not pollinate other specific cultivars. Check pollination requirements before you buy.

European pears are hardy to –20°F, but Asian pears generally are hardy only in Zones 5 and warmer. European and Asian pear varieties have a range of chilling requirements, so check on this when deciding what to grow. (For more information on fruit tree chilling requirements, see page 419.)

Fire blight can be a devastating disease problem in some regions, especially areas with warm, wet spring seasons. ‘Magness’ and ‘Warren’ are resistant to fire blight. ‘Magness’ doesn’t produce viable pollen, so be sure to plant it with two other cultivars. Asian pears seem to be less appealing to pear psylla, another common problem.

Rootstocks: Standard pear trees are grafted onto seedling rootstocks, but they can grow 30 feet tall. Semidwarf and dwarf varieties are easier to care for and harvest. Many dwarf and semi-dwarf pear trees are grafted onto quince rootstock. ‘Old Home × Farmingdale’ rootstock is resistant to fire blight and pear decline and makes a semidwarf tree.

Planting and care: Pear trees are quite winter hardy. They bloom early but tend to be more resistant to frost damage than other fruits. (Opened pear blossoms can be damaged at 26°F.)

Pears will tolerate less-than-perfect drainage but need deep soil. They are vulnerable to water stress, which causes foliage to turn brown and prevents fruits from enlarging. To prevent this, mulch with a thick layer of organic matter out to the drip line, and irrigate deeply if the soil dries out.

Pears prefer a pH of 6.4 to 6.8. If pH is too low, the tree may be more susceptible to fire blight. A healthy pear tree grows 1 to 1½ feet a year. If growth is less, have the foliage tested and correct any deficiencies. The Soil entry gives details on how to get foliage tested. Go easy when fertilizing with nitrogen; it encourages soft new growth that is susceptible to fire blight. If there is too much new growth on the tree, let weeds or grass grow up beneath the tree to consume excess nutrients in the soil.

Pruning: Pear trees grow tall. However, you can keep all the limbs within an arm’s reach of a ladder by training your young tree. How you choose to prune and train your tree will greatly affect its lifespan as well as its ability to produce large crops. Start training as soon as you plant your tree. Be sure to spread the branches, because pears tend to grow up, not out, if left on their own. Minimize pruning, because too much pruning can also stimulate more growth than you want.

If you develop a strong, spreading framework, it will be easier to prune, and the tree will bear earlier. When you do start to prune, prune just before the tree breaks dormancy in spring. Or in locations where pears suffer winter bud damage, prune just after flowering.

Train European pears to a central leader system and Asian pears to an open center system (see the Fruit Trees entry for pruning details). In areas where fire blight is severe, you may want to leave two main trunks as crop insurance.

To minimize fire blight attack on susceptible trees, discourage soft young growth, and make as few cuts as possible. Thin out whole branches rather than heading them back. This will reduce the total number of cuts made and won’t stimulate the growth of soft, highly susceptible side shoots. Snip off any flowers that appear in late spring or summer. They are an easy target for fire blight.

Remove unproductive and disease-susceptible suckers that sprout from the trunk and branches. As the tree gets older, you may want to leave a renewal sucker to replace a limb with 4- or 5-year-old spurs, or one damaged by fire blight. During summer, select a sucker near the base of the branch to be replaced. Spread the crotch so it will develop a good outward angle. Carefully remove the old branch the next spring so the sucker will have room to develop.

Thinning: Pears are likely to set more fruit than they can handle. Fruits will be small, and the heavy fruit load may break branches or prevent flowering the following year if not thinned. A few weeks after the petals fall, remove all but one fruit per cluster. Prop up heavily laden limbs with a forked stick.

Harvesting: Pears bear in 3 to 5 years after planting. Pick European pears before the flesh is fully ripe; the fruit will finish ripening off the vine. To test ripeness, cut a fruit open; dark seeds indicate ripe fruit. Also, if you can pull the fruit stem away from the branch with a slight effort but without tearing the wood, the fruit is prime for harvesting. Store pears at just above 32°F. Many European cultivars store well; hard, late-bearing cultivars store better than earlier cultivars. When you’re ready to eat them, place them in a 60° to 70°F room to soften and sweeten (putting them in a bowl with some bananas will speed their ripening). Pears that won’t ripen may have been in cold storage too long, or the ripening temperature may be too high. If a pear is brown and watery inside, it was harvested too late.

Asian pears are sweetest when allowed to ripen on the tree. Watch for a color change, and taste to decide when they are ripe.

Problems: Apple maggots, codling moths, green fruit worms, mites, and plum curculio can attack pears. For descriptions and control methods, see page 249. Pears also attract aphids, scale, and tarnished plant bugs; see page 458 for descriptions and controls. See the Apple entry for description and control of leafrollers and other leaf-eating caterpillars.

Pear psylla is a major pest in many areas. These tiny sucking insects are nearly invisible to the naked eye. They are often noticed only when the foliage and twigs at the top of pear trees turn black in late summer. The black color is actually a sooty mold that grows in the honeydew produced by the psylla. Left uncontrolled, psylla and sooty mold can reduce fruit production or even kill the tree. Psylla also can infect trees with viruslike diseases, such as pear decline. Native beneficial insects can help keep psylla in check. To prevent psylla problems, spray trees with kaolin clay beginning in spring, and if possible, keep the trees coated by repeat spraying all through the growing season. The psylla don’t like to lay their eggs on sprayed trees, and the clayey coating also irritates psylla nymphs.

Thrips are tiny insects too small to see, but you can see their small dark droppings on leaves. Leaves will appear bleached and wilted, fruit may show scabs or russeting. Predatory mites will control thrips, but if populations are high, spray with insecticidal soap.

Pearslugs are the small sluglike larvae of sawflies. They eat leaf tissue but leave a skeleton of veins behind. Hand pick, wash them off leaves with a strong water spray, or spray with insecticidal soap.

Fire blight, a bacterial disease that affects many fruit trees, is especially severe on pears. It can rapidly kill a susceptible tree or orchard in humid conditions. The sooty mold that goes with psylla can also look like fire blight. Sooty mold wipes off; fire blight doesn’t. For control measures, see page 249. Pear trees also suffer from cedar apple rust; see the Apple entry for description and controls.

Pseudomonas blight symptoms resemble fire blight, but it thrives in cool fall conditions when fire blight is less common. Control as for fire blight.

Pear scab looks much like apple scab. See the Apple entry for description and controls.

Fabraea leaf spot causes small, round, dark spots with purple margins. Leaves turn yellow and drop. Fruits develop dark, sunken spots and may be misshapen. If many leaves drop, trees are weakened, and future crops are reduced. Clean up fallen leaves each winter. If leaf spot has been a problem in the past, spray copper just before the blossoms open and again after the petals fall off.

Many viral diseases affect pears, causing leaf or fruit distortion and discoloration. Buy certified virus-free stock, and control insects such as aphids, which may transmit viruses.

PELARGONIUM

Pelargonium × hortorum, zonal geranium, garden geranium. Tender perennials grown as annuals or houseplants.

Description: Flower colors include white, pink, rose, red, scarlet, purple, and orange shades, plus starred, edged, banded, and dotted patterns of two or more colors. Pick from single (fivepetalled) or double forms resembling rosebuds, tulips, cactus flowers, or carnations. The rounded flower clusters may be very dense or quite open and airy, measuring 1 to 6 inches across. Geraniums normally grow 1 to 2 feet in a single season. Smaller sizes include miniature (3 to 5 inches), dwarf (6 to 8 inches), and semidwarf (8 to 10 inches). Upright, mounded, and cascading habits are available. The soft and fuzzy, rounded, scalloped, or fingered leaves can grow from ½ to 5 inches wide. Leaves may be all green, chartreuse and maroon, banded in dark green, or green combined with one or more shades of white, red, yellow, chartreuse, or brown.

Pelargonium peltatum, ivy geranium, brings color to window boxes and baskets throughout summer and fall. Clusters of white, red, pink, salmon, lavender, and purple flowers bloom profusely on trailing stems above shiny, scalloped, ivy-shaped leaves. Some of the many cultivars have variegated leaves, including ‘Crocodile’, with unusual yellow-netted leaves. Plants can grow 2 to 5 feet in a season. There are also more-compact hybrids between the ivy and garden (zonal) geranium.

Ivy geraniums are excellent hanging-basket plants. You can also grow them in the traditional window box, in a raised planter, or as a flowering groundcover.

P. × domesticum, Martha Washington or regal geraniums, are the glamour queens of the genus. They take the spotlight in cooler regions, where their 6-inch clusters of azalea-like flowers bloom profusely in white, pink, red, lavender, burgundy, salmon, violet, and bicolors. Rounded leaves up to 8 inches wide grow thickly on mounded 1- to 2-foot plants.

Spectacular in beds, regal geraniums also make great houseplants and dazzling standards. If you live where summers are hot, you can still enjoy these beauties as spring pot plants, discarding them after bloom.

How to grow: Buy blooming plants of cutting-grown cultivars from a nursery; try to buy locally grown cultivars that are suitable for your region, especially in the humid South. Or sow seeds in February for plants that will bloom by summer. Plant out after all danger of frost is past. Most prefer full sun, but shade variegated cultivars from the hottest afternoon sun to prevent leaf browning. Geraniums adapt to most well-drained soils with average moisture, although they prefer sandy loam. Avoid high-nitrogen fertilizers, which encourage leaf growth at the expense of flowers, unless you’re growing cultivars such as ‘Vancouver Centennial’ or ‘Crystal Palace Gem’ for their fabulous foliage. Pinch the tips of plants that are reluctant to branch on their own to avoid tall, leggy plants with leaves and flowers only toward the top. In late summer, root 4- to 5-inch cuttings in clean sand, or dig up your favorites and pot them before frost.

Scented Geraniums

Although not as colorful as zonal geraniums, scented geraniums (Pelargonium spp.) also deserve a place in your garden. A few of them have attractive blooms, producing small clusters of pink, white, or lavender flowers, but they’re really grown for their fragrant foliage. Leaf form varies from tiny ½-inch rounded leaves to 6-inch oaklike giants, but all release their powerful aromas with a gentle rub. Habit ranges from loose, spreading plants to strong bushes reaching 4 feet or more.

Scented geraniums require much the same care as zonal geraniums, but don’t overfeed them or the fragrance won’t be as strong. They grow well in pots of loose, well-drained soil, and their scented foliage makes them ideal houseplants. Grow them in your flower borders for a green accent, or show them off in an herb or kitchen garden. Both flowers and foliage are edible and can be used fresh or dried in herb teas.

There are many, many scented geraniums available. The list here is only a small sample.

| NAME | FRAGRANCE |

| Pelargonium crispum | Lemon |

| P. denticulatum | Pine |

| P. fragrans | Nutmeg |

| P. graveolens | Rose |

| P. ✕ nervosum | Lime |

| P. odoratissimum | Apple |

| P. scabrum | Apricot |

| P. tomentosum | Peppermint |

Hybrids between these and other species have given rise to many cultivars, among them ‘Grey Lady Plymouth’, with rose-scented, gray-green leaves edged in white; ‘Mabel Gray’, with an intense lemon fragrance and sharply lobed leaves; and ‘Prince Rupert Variegated’, bearing small, cream-and white-variegated lemony foliage.

Buy ivy geraniums in bloom to set in sunny spots but provide afternoon shade in summer. Water container plants frequently, but don’t let them stand in water. Use a rich, well-drained potting mix and feed monthly with liquid organic fertilizer. Pinch back for more flowers.

Set purchased regal geranium plants in a sunny, cool spot with good, slightly alkaline soil. They require plenty of water while in bloom. Treat them as true annuals and discard at season’s end, or take cuttings or pot up plants to bring indoors for winter.

Landscape uses: Mass geraniums in beds of their own, or use them to brighten a mixed border. Geraniums in containers will light up a deck, patio, or sunny porch; if you use them in a sitting area, choose plants with attractively colored foliage as well as showy flowers for double the viewing pleasure. Use ivy geraniums in hanging baskets. Plants may live for years in pots, and look especially handsome if trained into standards. (For more information on creating standards, see page 315.) Fill a window box with a single color or a mixture, and add splashes of color to slightly shaded corners or areas under tall trees with variegated types.

PENSTEMON

Penstemon, beardtongue. Late-spring-to summer-blooming perennials; wildflowers.

Description: Penstemons produce clusters of tubular flowers with scalloped tips and a fuzzy area (beard) inside the throat. Flowers range from white to pink, red, scarlet, orange, wine, and indigo. They bloom at the ends of creeping or 1- to 3-foot upright stems bearing pointed, often evergreen leaves. Zones 3–9, depending on the species. Many penstemons are common wildflowers in the West; only a few species are native to the eastern United States. The best bet for Eastern gardens is the white-flowered Penstemon digitalis, foxglove penstemon, and its cultivars, such as ‘Husker Red’, which has deep red foliage and pink flowers. Unlike other penstemons, it thrives in moist soil. Zones 4–8.

How to grow: Plant or divide in spring in sunny, average, very well-drained soil. Provide partial shade in warmer areas. Mulch with gravel or other inorganic material; organic matter holds too much moisture and will rot the crowns. Divide clumps every 4 to 6 years to maintain vigor.

Landscape uses: Use penstemons as a filler in borders and beds and in rock gardens.

PEONY

See Paeonia

PEPPER

Capsicum annuum var. annuum

Solanaceae

Pepper choices—ranging from crispy sweet to fiery hot, from big and blocky to long and skinny—increase each year. This native American vegetable is second only to tomatoes as a garden favorite, and it needs much the same care. Peppers are also ideal for spot planting around the garden. The brilliant colors of the mature fruit are especially attractive in flower beds and in container plantings.

New varieties of bell peppers are released every year, in mature colors ranging from bright red to orange to white, purple, and nearly black. If you’ve had past problems with diseases such as tobacco mosaic virus or bacterial spot, choose disease-resistant varieties.

Planting: Choose a site with full sun for your pepper plot. Don’t plant peppers where tomatoes or eggplants grew previously, because all three are members of the nightshade family and are subject to similar diseases. Make sure the soil drains well; standing water encourages root rot.

Garden centers offer a good variety of transplants, but the choices are greater when you grow peppers from seed. Pepper roots don’t like to be disturbed, so plant them indoors in peat pots two months before the last frost date, sowing three seeds to a pot. Maintain the soil temperature at 75°F, and keep the seedlings moist, but not wet. Provide at least 5 hours of strong sunlight a day, or ideally, keep the plants under lights for 12 or more hours daily. Once the seedlings are 2 to 3 inches tall, thin them by leaving the strongest plant in each pot and cutting the others off at soil level.

Seedlings are ready for the garden when they are 4 to 6 inches tall. Before moving the young plants to the garden, harden them off for about a week. Peppers are very susceptible to transplant “shock,” which can interrupt growth for weeks. To avoid shocking the plants, make sure the soil temperature is at least 60°F before transplanting; this usually occurs 2 to 3 weeks after the last frost. Transplant on a cloudy day or in the evening to reduce the danger of sun scorch; if this is not possible, provide temporary shade for the transplanted seedlings.

When buying transplants, look for ones with strong stems and dark green leaves. Pass up those that already have tiny fruits on them, because such plants won’t produce well. Peppers take at least 2 months from the time the plants are set out to the time they produce fruit, so short-season growers should select early-maturing cultivars.

Space transplants about 1½ feet apart in rows at least 2 feet apart, keeping in mind that most hot-pepper cultivars need less room than sweet ones. If the plot is exposed to winds, stake the plants, but put these supports in place before transplanting the seedlings to keep from damaging roots. To deter cutworms, place a cardboard collar around each stem, pushing it at least an inch into the ground. If the weather turns chilly and rainy, protect young plants with hotcaps.

Growing guidelines: Evenly moist soil is essential to good growth, so spread a thick but light mulch, such as straw or grass clippings, around the plants. Water deeply during dry spells to encourage deep root development. Lack of water can produce bitter-tasting peppers. To avoid damaging the roots, gently pull any invading weeds by hand.

Although peppers are tropical plants, temperatures over 90°F often cause blossoms to drop and plants to wilt. To avoid this problem, plan your garden so taller plants will shade the peppers during the hottest part of the day. If you plant peppers in properly prepared soil, fertilizing usually isn’t necessary. Pale leaves and slow growth, however, are a sign that the plants need a feeding of liquid fertilizer, such as fish emulsion or compost tea. See the Compost entry for instructions for making compost tea.

Problems: Since sprays of ground-up hot peppers can deter insects, it’s logical that pests don’t usually bother pepper plants. There are, however, a few exceptions. The pepper weevil, a ⅛-inch-long, brass-colored beetle with a brown or black snout, and its ¼-inch-long larva, a white worm with a beige head, chew holes in blossoms and buds, causing misshapen and discolored fruits. It’s a common pest across the southern United States. Prevent damage by keeping the garden free of crop debris. Hand pick any weevils you spot on the plants.

Other occasional pests include aphids, Colorado potato beetles, flea beetles, hornworms, and cutworms. See page 458 for information on these insect pests and how to control them.

Crop rotation and resistant cultivars are your best defense against most pepper diseases. Here are some common diseases to watch for:

Anthracnose infection causes dark, sunken, soft, and watery spots on fruits.

Anthracnose infection causes dark, sunken, soft, and watery spots on fruits.

Bacterial spot appears as small, yellow-green raised spots on young leaves and dark spots with light-colored centers on older leaves.

Bacterial spot appears as small, yellow-green raised spots on young leaves and dark spots with light-colored centers on older leaves.

Early blight appears as dark spots on leaves and stems; infected leaves eventually die.

Early blight appears as dark spots on leaves and stems; infected leaves eventually die.

Verticillium wilt appears first on lower leaves, which turn yellow and wilt.

Verticillium wilt appears first on lower leaves, which turn yellow and wilt.

Mosaic—the most serious disease—is a viral infection that mottles the leaves of young plants with dark and light splotches and eventually causes them to curl and wrinkle. Later on, mosaic can cause fruits to become bumpy and bitter.

Mosaic—the most serious disease—is a viral infection that mottles the leaves of young plants with dark and light splotches and eventually causes them to curl and wrinkle. Later on, mosaic can cause fruits to become bumpy and bitter.

See the Plant Diseases and Disorders entry for more information on some of these diseases and control measures.

Harvesting: Most sweet peppers become even sweeter when mature as they turn from green to bright red, yellow, or orange—or even brown or purple. Mature hot peppers offer an even greater variety of rainbow colors, often on the same plant, and achieve their best flavor when fully grown. Early in the season, however, it’s best to harvest peppers before they ripen to encourage the plant to keep bearing; a mature fruit can signal a plant to stop production.

Always cut (don’t pull) peppers from the plant. Pick all the fruit when a frost is predicted, or pull plants up by the roots and hang them in a dry, cool place indoors for the fruit to ripen more fully. To preserve, freeze peppers (without blanching), or dry hot types.

PERENNIALS

Perennials are part of our lives, even if we’re not flower gardeners. Most of us grew up with day-lilies, irises, and peonies in our yards or neighborhoods, and perennials like astilbes and hostas are familiar faces too. But many less-well-known perennials have an exotic mystique: We may admire them, but we’re not sure we’d know what to do with them in our own gardens.

Technically speaking, most plants grown in the garden are perennial, if you count every plant that lives more than a year, including trees and shrubs. But to most gardeners, a perennial is a plant that lives and flowers for more than one season but dies to the ground each winter.

Many perennials—including peonies (Paeonia spp.), Oriental poppies (Papaver orientalis), and daylilies (Hemerocallis spp.)—are long-lived. Others, like coreopsis and columbines (Aquilegia spp.), may bloom just a few years before disappearing, but they are prolific seeders, and new seedlings keep coming back just like their longer-lived cousins. Most popular perennials fall somewhere between the two extremes, and will reappear year after year with reassuring regularity.

Landscaping with Perennials

Perennials are all-purpose plants—you can grow them wherever you garden and in any part of your garden. There’s a perennial to fit almost any spot in the landscape, and with a little planning, it’s possible to have them in bloom throughout the frost-free months. In addition to the endless variety of sizes, shapes, colors, and plant habits, there are perennials for nearly any cultural condition your garden has to offer.

Most perennials prefer loamy soil with even moisture and full sun. Gardeners who have these conditions to offer have the widest selection of plants from which to choose. However, if you have a shaded site, there are dozens of perennials for you, too, such as those listed on page 432. For ideas for other types of sites, see the lists on pages 433 and 437 as well.

Perennials add beauty, permanence, and seasonal rhythm to any landscape. Their yearly growth and flowering cycles are fun to follow—it’s always exciting to see the first peonies pushing out of the ground in April or the asters braving another November day. Look at your property and think about where you could add perennials. There are a number of ways to use perennials effectively in your yard.

Shade gardens: Turn problem shady sites where lawn grass won’t grow, such as under trees or between buildings, into an asset by creating a shade garden. Many perennials tolerate shade, but remember that shade plants often have brief periods of bloom. For the most successful shade garden, you should count on the plants’ foliage to carry the garden through the seasons. The most engaging shade gardens rely on combinations of large-, medium-, and small-leaved plants with different leaf textures. For example, try mixing ferns with variegated hostas, astilbes, Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica), and shade-tolerant groundcovers like Allegheny foam-flower (Tiarella cordifolia) and creeping phlox (Phlox stolonifera) to create a diverse mix of size, foliage, and texture.

Bog and water gardens: If you have a low area that’s always wet, you know that fighting to grow grass there is a losing battle. Instead, turn that boggy patch into a perennial bog or water garden. Some perennials will even grow with their roots submerged in the shallows. For more on making a bog or water garden, see the Water Gardens entry.

Rock gardens: If you have a rock wall that edges a bank or a dry, stony slope in full sun, you have a perfect site for a rock garden. A host of plants thrive in poor soil and relentless sunshine, including yarrows, sedums, and hens-and-chicks. For more on rock gardening, see the Rock Gardens entry. (For a design featuring a rock garden, see page 638.)

Containers: To add color and excitement to a deck, patio, balcony, or entryway, try perennials in containers. Mix several perennials together, combine them with annuals, or plant just a single perennial per container. Try a daylily in a half barrel in a sunny spot or hostas with variegated foliage in a shady one. Remember, containers dry out quickly, so choose plants that tolerate some dryness for best results. For more ideas, see the Container Gardening entry.

Perennial plant of the year: Every year, the Perennial Plant Association (PPA), the professional organization for the promotion of perennial plants, announces the winner of its Perennial Plant of the Year competition. The PPA is composed of nurserymen, perennial plant breeders, educators, landscape and garden designers, and others with a serious interest in perennial plants. Each year, the membership nominates the plants they feel deserve the honor of being named Perennial Plant of the Year, based on such criteria as consistency, low maintenance, ornamental value in multiple seasons, pest and disease resistance, wide adaptability to a range of climatic conditions, easy propagation, and wide availability. What this means is that gardeners can count on the winning perennials to perform well in their gardens, wherever they live, with minimal care.

KEY WORDS Perennials

Perennial plant. A plant that flowers and sets seed for two or more seasons. Short-lived perennials like coreopsis and columbines may live 3 to 5 years. Long-lived perennials like peonies may live 100 years or more.

Tender perennial. A perennial plant from tropical or subtropical regions that can’t be overwintered outside, except in subtropical regions such as Florida and Southern California. Often grown as annuals, tender perennials include zonal geraniums, wax begonias, cannas, and coleus.

Hardy perennial. A perennial plant that tolerates frost. Hardy perennials vary in the degree of cold that they can tolerate, however, so make sure a plant is hardy in your zone before you buy it.

Herbaceous perennial. A perennial plant that dies back to the ground at the end of each growing season. Most garden perennials fall into this category.

Semiwoody perennial. A perennial plant that forms woody stems but is much less substantial than a shrub. Examples include lavender, Russian sage, and some of the thymes.

Woody perennial. A perennial plant such as a shrub or tree that does not die down to the ground each year. Gardeners generally refer to these as “woody plants.”

You can’t go wrong by adding these great perennials to your garden. You’ll find more information on the Perennial Plant of the Year program on the Internet; see Resources on page 672 for the address.

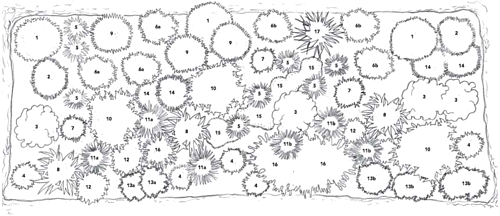

Designing Beds and Borders

Designing with perennials may seem overwhelming, since there are so many to choose from. Just take your design one step at a time. Chances are, your growing conditions are right for only a fraction of what’s available. Let your moisture, soil, and light conditions guide you in choosing plants. For example, if you have a garden bed in full sun that tends toward dry soil, cross off shade-and moisture-loving perennials like hostas and ferns from your list. Instead, put in plants that like full sun and don’t like wet feet, like daylilies and ornamental grasses. And don’t forget to choose only plants that are hardy in your area. For information on combining perennials to create a lush bed or border, see the Garden Design entry.

Planting Perennials

Because perennials live a long time, it’s important to get them off to a good start. Proper soil preparation and care at planting time will be well rewarded.

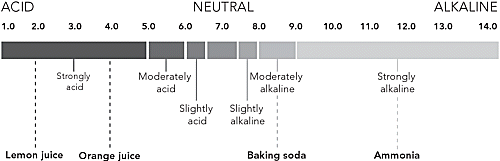

Soil preparation: The majority of perennials commonly grown in beds or borders require evenly moist, humus-rich soil of pH 5.5 to 6.5. A complete soil analysis from your local extension office or a soil-testing lab will give you a starting point. For more on soils and do-it-yourself soil tests, see the Soil entry.

Best Perennials for Shade

There are dozens of choice perennials to brighten a shady site. Most prefer woodland conditions: rich, moist, well-drained soil and cool temperatures. Many plants in this list grow well in partial shade. Plants that tolerate deep shade include species of Actaea, Brunnera, Epimedium, Heuchera, Hosta, Mertensia, Polygonatum, and Pulmonaria. Plant name is followed by bloom time and color.

Aconitum spp. (monkshoods): summer to early fall; blue

Actaea spp., formerly Cimicifuga spp., (bugbanes): summer to fall; white

Aquilegia spp. (columbines): spring to early summer; all colors, bicolors

Astilbe spp. (astilbes): late spring to summer; red, pink, white, purple

Bergenia spp. (bergenias): early spring; rose, pink, purple, white

Brunnera macrophylla (Siberian bugloss): spring; light blue

Dicentra spp. (bleeding hearts): spring; rose pink, white

Epimedium spp. (epimediums): spring; pink, red, yellow, white

Helleborus spp. (hellebores): early spring; white, rose, green, purple

Heuchera spp. (heucheras, coral bells): spring to summer; pink, red, white, green

× Heucherella tiarelloides (foamy bells): spring and summer; pink, white, cream

Hosta spp. (hostas): early to late summer; violet, lilac, white

Mertensia virginica (Virginia bluebells): spring; blue, white

Polemonium spp. (Jacob’s ladders): spring to summer; blue, pink, white, yellow

Polygonatum spp. (Solomon’s seals): spring; white, greenish white

Pulmonaria spp. (lungworts): spring; purple-blue, blue, red

Tiarella cordifolia (tiarella, foamflower): spring; white, pink

Dig deep when you prepare your perennial bed. Plants’ roots will be able to penetrate the friable soil easily, creating a strong, vigorous root system. Water and nutrients will also move easily through the soil, and the bed won’t dry out as fast. As a result, your plants will thrive. Have any necessary soil amendments and organic fertilizers on hand before you start, and add them to the bed once you’ve worked it.

Turn the soil evenly to a shovel’s depth at planting time. Thoroughly incorporate appropriate soil amendments and fertilizer as required. Break up all clods and smooth out the bed before planting. For soil preparation techniques see the Soil entry. If your soil is particularly bad or you’d like to avoid the effort involved in digging a garden, try techniques outlined in the Raised Bed Gardening entry.

Perennials with Striking Foliage

Most perennials bloom for only a few weeks, so it makes sense to think about what they’ll look like the rest of the season. These dual-purpose perennials have especially interesting foliage when not in flower. Try species of Ajuga, Asarum, Bergenia, Epimedium, Hosta, Lamium, Liriope, Saxifraga, Sedum, Sempervivum, Stachys, and Tiarella for three-season interest, and don’t forget ferns and ornamental grasses. Plant name is followed by foliage interest.

Acanthus spp. (bear’s-breeches): shiny; lobed or heart-shaped; spiny

Ajuga reptans (ajuga): striking variegations and colors, including gray, green, pink, and purple

Alchemilla mollis (lady’s-mantle): maple-like; chartreuse

Artemisia spp. (artemisias): ferny; silver or gray; aromatic

Asarum spp. (wild ginger): leathery; glossy or matte; dark green

Bergenia spp. (bergenias): glossy; evergreen; burgundy fall color

Heuchera spp. (alumroots): maplelike; dark purple, silver, reddish, green, often with contrasting veins

Hosta spp. (hostas): smooth; puckered; variegated; green, blue-gray, chartreuse, yellow, cream, white

Houttuynia cordata (houttuynia): heart-shaped; shiny; variegated forms

Lamium spp. (lamiums): green-, yellow-, white-variegated

Polygonatum odoratum (Solomon’s seal): long, graceful shoots; variegated forms

Pulmonaria spp. (lungworts): dark green; gray-or silver-spotted

Rodgersia spp. (rodgersias): huge; maple-like or buckeyelike; bronze

Saxifraga stolonifera (strawberry geranium): silver-veined; reddish undersides

Sedum spp. (sedums): fleshy; many colors; variegated forms

Sempervivum spp. (hens-and-chicks): fleshy rosettes; some red-or purple-tinged

Stachys byzantina (lamb’s-ears): white, gray green, yellow; velvety

Tiarella cordifolia (Allegheny foamflower): maplelike; green with red or purple veining; evergreen

Yucca spp. (yuccas): sharply pointed; large; evergreen; variegated forms

Planting: Plant perennials any time the soil is workable. Spring and fall are best for most plants. If plants arrive before you are ready to plant them, be sure to care for them properly until you can get them in the ground.

Planting is easy in freshly turned soil. Choose an overcast day whenever possible. Avoid planting during the heat of the day. Place container- grown plants out on the soil according to your design. To remove the plants, invert containers and knock the bottom of the pot with your trowel while keeping one hand spread over the soil on top so the plant doesn’t fall to the ground and snap off. The plant should fall out easily. The roots will be tightly intertwined. It’s vital to loosen the roots—by pulling them apart or even cutting four slashes, one down each side of the root mass—so they’ll spread strongly through the soil when planted out. Clip any roots that are bent, broken, or circling. Make sure you place the crown of the plant at the same depth at which it grew in the pot.

Perennials for the North

These perennials flourish in the cooler summers of Northern zones and withstand cold winters to Zone 3. Species of Campanula, Delphinium, Hemerocallis, Papaver, Penstemon, Phlox, Primula, and Veronica are hardy to Zone 2. Many of these same plants will grow as far south as Zone 9, but only a few prosper under hot, humid conditions. Plant name is followed by bloom time and color.

Achillea spp. (yarrows): spring to summer; yellow, white, red, terra-cotta, pink, purple, cream

Actaea racemosa, formerly Cimicifuga racemosa, (black snakeroot): late summer; white

Aquilegia spp. (columbines): spring to early summer; all colors, bicolors

Campanula spp. (bellflowers): spring to summer; blue, white, purple

Delphinium spp. (delphiniums): summer; blue, red, violet, white

Dianthus spp. (pinks): spring; pink, red, white, yellow

Dicentra spp. (bleeding hearts): spring; rose pink, white

Gypsophila spp. (baby’s-breath): summer; white, pink

Hemerocallis spp. (daylilies): spring to summer; all colors except blue

Hosta spp. (hostas): early to late summer; violet, lilac, white

Iris spp. (irises): spring to summer; all colors, bicolors

Papaver orientale (Oriental poppy): early summer; scarlet, pink, white, purple

Penstemon barbatus (common beard-tongue): spring; pink, white

Phlox spp. (phlox): early spring to summer; pink, white, blue

Primula spp. (primroses): spring; all colors

Rudbeckia spp. (coneflowers): summer; yellow

Sedum spp. (sedums): spring to fall; yellow, pink, white

Thermopsis spp. (false lupines): spring; yellow

Veronica spp. (veronicas, speedwells): spring to summer; blue, white, pink