QUERCUS

Oak. Large deciduous or evergreen trees.

Description: Large shade trees with toothed or lobed leaves, oaks are pyramidal trees when young, developing a rounded to spreading habit with age. With the exception of Quercus acutissima, and Q. robur, all the species listed here are native in some part of North America.

Q. acutissima, sawtooth oak, grows 35 to 45 feet in the landscape. Its oblong leaves with bristlelike teeth usually turn brown and persist through winter. Zones 6–8.

Q. alba, white oak, grows 60 to 80 feet in the landscape; its most outstanding feature is the ash gray bark layered on its trunk. The leaves have rounded lobes and turn to shades of red and russet late in fall. Zones 3–8.

Q. imbricaria, shingle oak, has oblong, leathery, deep green leaves that turn brown in autumn and often persist on the tree well into winter, rattling in the wind. This native tree tolerates limestone soils well. Zones 5–7.

Q. macrocarpa, bur oak, is a massive native of the North American prairie. Growing 70 to 80 feet tall, it has imposing limbs, a wide trunk, and deeply furrowed bark. The leaves have rounded lobes and can grow up to 10 feet long. The cup on the acorn is fringed. Bur oak also performs well in limestone soils. Zones 2–7.

Q. palustris, pin oak, is a popular lawn tree with a strongly pyramidal form and a mature height of 60 to 70 feet. The leaves are sharply lobed and may develop chlorosis (yellowing) when the tree is grown in limestone soils. Zones 5–8.

Q. phellos, willow oak, is similar in form, size, and popularity to pin oak, but has smooth narrow leaves about 4 inches long. Some consider its leaf size and shape to make for easier cleanup in fall because the leaves don’t mat and tend to disappear amid groundcovers. Zones 6–9.

Q. robur, English oak, is a sturdy tree with a short trunk, deeply furrowed, dark gray bark, and a broadly spreading to rounded crown. Dark green, alternate leaves are 2 to 5 inches long with rounded lobes; like other oaks native to Europe, fall color is not significant. English oak reaches heights of 40 to 60 feet. Zones 5–8.

Q. rubra, red oak, is a vigorous tree that matures to 60 to 75 feet in the landscape. Lobes are sharply pointed to rounded on shiny dark green leaves; red fall color is not always strong. Red oak tolerates air pollution but may show leaf chlorosis in limestone soils. Zones 4–8.

Q. virginiana, live oak, is an evergreen native of the southeastern coastal forest. Massive and sprawling, live oak grows 40 to 80 feet in the landscape and often larger in the wild. Its elongated oval leaves are shiny dark green above and felted beneath. The huge boughs often host other plants such as Spanish moss and mistletoe. Coastal areas of Zones 7–10.

How to grow: Choose a site with full sun, well-drained, humusy soil, and plenty of room. Although adaptable to a variety of soil conditions, oaks generally perform better in acidic soils. Prune oaks during dormancy to avoid spreading oak wilt, a fungal disease that causes leaves to curl, brown, and droop. Oak wilt moves rapidly through a tree, often killing it within a year. Susceptibility varies among species; white, bur, English, and live oaks show resistance. The disease is more likely to be fatal to red, pin, sawtooth, shingle, and willow oaks. The fungus travels via root grafts; dig a trench between infected and healthy trees to destroy root connections. There is no cure for oak wilt.

The foliage of oaks is a favored food of gypsy moth larvae. Identified by the rows of blue and red stripes along their backs, these 2½-inch hairy gray caterpillars often occur in sufficient numbers to defoliate a tree, and repeated leaf loss causes severe decline and death. Egg masses appear as tan or buff fluffy patches on tree trunks and branches, buildings, and fences; scrape these off into a bucket of soapy water. Tie bands of burlap around tree trunks to capture climbing larvae; crush or hand pick trapped caterpillars. Spray Btk (Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki) to control young caterpillars.

Homeowners are often alarmed by unusual swellings of their oak’s leaves, floral parts, or twigs; such galls are caused by various insects and mites. Not all galls injure their hosts, but some kill twigs and branches. Remove and destroy galls to limit further infestation. Spray young trees with dormant oil in late winter to kill overwintering gall-forming pests.

Landscape uses: Use any of these oaks as long-lasting shade trees; in a large-scale situation, they make fine focal points as well. Most bear acorns that attract wildlife. Good street-tree choices are sawtooth and willow oaks. Look to native oaks if your landscape needs include colorful autumn leaves.

RADISH

Raphanus sativus

Brassicaceae

Colorful and crisp, radishes are a popular addition to salads and vegetable trays. Radishes mature very quickly—some in as little as 3 weeks. They’re a useful marker crop when sown lightly along rows of slow germinators such as carrots and parsnips.

Planting: Dig the soil to a depth of 6 inches for quick-growing radishes and up to 2 feet for large, sharper-tasting, slower-growing winter types. Space seeds ½ inch deep and 1 inch apart; firm the soil and water gently. Make weekly spring sowings as soon as you can work the soil (4 to 6 weeks before the last expected frost) until early summer; start again in late summer. Sow winter radishes in midsummer for a fall harvest.

Growing guidelines: Thin seedlings to 2 inches apart, 3 to 6 inches for the larger winter types. Mulch to keep down weeds. For quick growth and the best flavor, water regularly.

Problems: Cabbage maggots are attracted to radishes but seldom ruin a whole crop; for controls, see page 458.

Harvesting: Pull as soon as the roots mature. Oversized radishes often crack and are tough or woody.

RAISED BED GARDENING

For space efficiency and high yields, it’s hard to beat a vegetable garden grown in raised beds. Raised beds can improve production as well as save space, time, and money. They also are the perfect solution for dealing with difficult soils such as heavy clay. In addition, raised beds improve your garden’s appearance and accessibility.

Raised gardening beds are higher than ground level, and consist of soil that’s mounded or surrounded by a frame to keep it in place. The beds are separated by paths. Plants cover the entire surface of the bed areas, while gardeners work from the paths. The beds are usually 3 to 5 feet across to permit easy access from the paths, and they may be any length. You can grow any vegetable in raised beds, as well as herbs, annual or perennial flowers, berry bushes, or even roses and other shrubs.

One reason raised beds are so effective for increasing efficiency and yields is that crops produce better because the soil in the beds is deep, loose, and fertile. Plants benefit from the improved soil drainage and aeration, and plant roots penetrate readily. Weeds are easy to pull up, too. Since gardeners stay in the pathways, the soil is never walked upon or compacted. Soil amendments and improvement efforts are concentrated in the beds and not wasted on the pathways, which are simply covered with mulch or planted with grass or a low-growing cover crop. Also, the raised bed’s rounded contour provides more actual growing area than does the same amount of flat ground.

Raised beds also save time and money because you need only dig, fertilize, and water the beds, not the paths. You don’t need to weed as much when crops grow close together, because weeds can’t compete as well. Gardeners with limited mobility find raised beds the perfect solution—a wide sill on a framed raised bed makes a good spot to sit while working. A high frame puts plants in reach of a gardener using a wheelchair. For best access, make beds 28 to 30 inches high, and also keep the beds narrow—no more than 4 feet wide—so it’s easy to reach to the center of the bed.

Many gardeners have written entire books about their method of using raised beds to produce great gardening results. For titles, see Resources on page 672.

Building Raised Beds

The traditional way to make a raised bed is to double dig. This process involves removing the topsoil layer from a bed, loosening the subsoil, and replacing the topsoil, mixing in plenty of organic matter in the process. Double digging has many benefits, but can be time consuming and laborious. See the Soil entry for details.

The quickest and easiest way to make a raised bed is simply to add lots of organic matter, such as well-rotted manure, compost, or shredded leaves to your garden soil. In the process, mound up the planting beds as the organic content of the soil increases. Shape the soil in an unframed bed so that it is flat-topped, with sloping sides (this shape helps conserve water), or forms a long, rounded mound. The soil in an unframed bed will gradually spread out, and you’ll need to periodically hill it up with a hoe. A frame around the outside edge of the bed prevents soil from washing away and allows you to add a greater depth of improved soil. Wood, brick, rocks, or cement blocks are popular materials for framing. Choose naturally rot-resistant woods such as cedar, cypress, or locust. If you choose some other type of wood (don’t use chemically-treated wood), keep in mind that you’ll need to replace it when the wood eventually wears and rots away.

If your garden soil is difficult—heavy clay, very alkaline, or full of rocks—you may want to mix your own soil from trucked-in topsoil, organic matter, and mineral amendments. Then you can build beds up from ground level, without disturbing or incorporating the native soil. You may also need to add extra materials to raised beds if you want them to be tall enough for a gardener in a wheelchair to reach easily.

Lasagna Gardening

This is a no-till option for building raised beds and great soil. It is similar to sheet composting, and allows you to build raised beds without stripping grass or weeds off the site. You can also build a lasagna garden on top of an existing vegetable garden site.

If you are starting on a new site, first cut the grass as short as possible and/or scalp the weeds at ground level. Next cover the bed with a thick layer of newspaper (6 to 10 sheets) to smother existing vegetation. Use sheets of cardboard or flattened cardboard boxes if there are vigorous perennial weeds on the site. Either wet down the newspapers as you spread them or have a supply of soil or mulch at hand and weigh them down with handfuls as you spread. Be sure to overlap the edges of the newspaper or cardboard as you work.

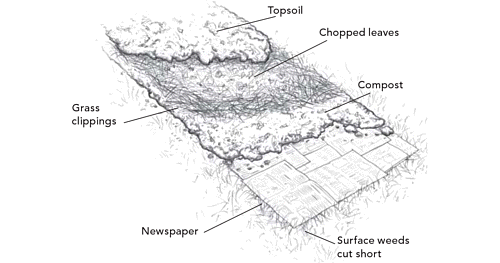

Gardening in layers. To make a lasagna garden, spread newspapers or cardboard to smother existing vegetation, then pile layers of grass clippings, chopped leaves, kitchen scraps, finished compost, and topsoil.

After that, begin layering organic matter on top of the site. Combine materials as you would in a compost pile, by mixing “browns” and “greens.” (See the Compost entry for more information.) Add layers of organic materials such as grass clippings, finished compost, chopped leaves, kitchen scraps, coffee grounds, seaweed, shredded mail or newspaper, garden trimmings, used potting soil, sawdust, and weeds (don’t add ones that have gone to seed or perennials with vigorous rhizomes, which will spread and grow in the bed). You can also add topsoil, which will help speed things along. Make a pile that is 1 feet or more deep, and top it off with a layer of mulch to keep weeds from getting a foothold. Then wait several months for materials to decompose.

You can build a lasagna garden any time of year. Building one in fall to plant in spring is a good idea, and there are plenty of leaves available for chopping and adding to the mix. If you’re building in spring or summer, you can speed up the time when it will be ready to plant by adding extra compost and topsoil in the mix. Top the bed with 2 to 3 inches of topsoil and/or compost for annual crops (more for perennial plants) and then plant seedlings directly into the topsoil/compost mix.

Intensive Gardening

Rich soil coupled with intensive gardening practices are what make raised bed gardening so successful. Intensive horticulture has been practiced for centuries in many parts of the world. In America, one of the best-known methods is French intensive gardening. Intensive gardening methods all have their own disciplines, but all use raised growing beds, close spacing between plants, careful attention to building and maintaining soil fertility, and succession planting to make the best use of available growing space.

Applied skillfully, intensive growing methods can (and consistently do) produce harvests 4 to 10 times greater than might be expected from a conventional garden. But intensive gardening also demands more initial work, planning, and scheduling than row gardens. If you wish to convert to intensive methods, it’s best to start gradually. For example, you could try building one or two raised beds each gardening season for a few years.

Plantings managed using intensive planting systems require fertile, well-balanced soil rich in organic content. Without plentiful additions of compost along with soil amendments, intensively gardened soil soon loses its vitality. Cover crops or green manures also help keep the soil fertile. See the Fertilizers, Compost, Cover Crops, and Soil entries for more information on soil management.

Close Plant Spacing

One reason that raised beds are so productive is that they are planted intensively, putting as much as 80 percent of a garden’s surface area into crop production. Pathways and spaces between crop rows make up the remainder. Plants are placed close together over the entire bed, usually in a triangular or staggered pattern, so that their leaves overlap slightly at maturity. This allows for more plants per square foot, and produces a continuous leafy canopy that shades the bed, moderates soil temperature, conserves moisture, and discourages weeds. Close spacing also means plantings must be carefully planned according to each crop’s growing habits, including root spread, mature size, and water and nutrient needs.

Succession Planting

Another technique used to maximize harvests in raised bed gardens is succession planting, which is the practice of rapidly filling the space vacated by a harvested crop by planting a new crop. This can be as simple as following harvested cool-season spring vegetables, such as peas or spinach, with a planting of warm-season summer crops, such as beans or squash. Once harvested, those crops could be followed by a cold-tolerant fall crop such as spinach. Another technique is to stagger plantings at 1- or 2-week intervals to prolong the harvest. Advanced intensive gardeners also interplant compatible short-, mid-, and full-season vegetables in the same bed at the same time. They then harvest and replant the faster-growing plants two, three, or even four times during the season.

RASPBERRY

See Brambles

RECYCLING

See Compost; Green Gardening

RHODODENDRON

Rhododendron, azalea. Spring-or summer-blooming broad-leaved evergreen or deciduous shrubs.

Description: Rhododendron arborescens, sweet azalea, is an upright, horizontally layered native deciduous shrub growing to 10 feet. Fragrant, trumpet-shaped white flowers appear in late spring. The leaves usually turn red before they fall. Zones 5–8.

R. calendulaceum, flame azalea, is an upright, layered native species growing 5 to 10 feet tall. Its orange-yellow to red flowers appear in spring either before or with the deciduous medium green leaves. Zones 5–8.

R. schlippenbachii, royal azalea, is a deciduous species that blooms in late spring. Flowers are fragrant, pale to rose pink, and spotted in the throat with light red-brown. Grows to 15 feet; turns yellow to orange-red in fall. Zones 5–8.

R. catawbiense, catawba rhododendron, is a spreading native evergreen species with thick, leathery leaves, sometimes growing 15 feet or more, though usually closer to 6 feet. This native bears large trusses of lilac-colored blooms in late spring. Zones 4–7.

R. mucronulatum, Korean rhododendron, is a deciduous shrub growing to 8 feet. The purple flowers appear in late winter or early spring before the leaves. Zones 5–7.

R. yakusimanum, Yaku rhododendron, is an evergreen with a mounded, compact habit, growing 3 feet tall and wide. Pink or white flowers appear in late spring. Zones 6–7.

Hybrid rhododendrons and azaleas are extremely popular landscape plants and have been developed for flower form and color as well as other characteristics. There are groundcover azaleas that reach only 12 inches tall but spread to several feet wide, as well as rhododendrons and azaleas selected for their hardiness or tolerance of heat and humidity. For best results, look for hybrids recommended for your area and climate conditions.

How to grow: Provide azaleas and rhododendrons with partial to full shade, good drainage, even moisture, and humus-rich soil. Site evergreen rhododendrons out of direct wind and deadhead them when the blooms are spent, pruning only to remove dead wood or to correct stray branches. Deciduous azaleas rarely need pruning (except to remove dead wood), but evergreen azaleas usually need post-bloom pruning to keep their size in scale. Azalea lace bugs are tiny insects that damage foliage by sucking sap from the undersides of leaves (use a hand lens to look for these bugs with lacy-looking wings or their spiny black nymphs). Leaves become splotched and grayish above, rusty below. Lace bugs can be especially troublesome on plants growing in sunny sites. Try washing them off plants with a strong spray of water or apply insecticidal soap. Fungi can attack rhododendron and azalea f lowers and foliage, especially when conditions are wet or humid. Minimize these with good sanitation (fungal diseases often overwinter in ground litter) and by removing infected parts with pruners sanitized between cuts.

Landscape uses: Azaleas and rhododendrons are great in a woodland garden setting, either as specimens or in massed plantings.

RHUBARB

Rheum × cultorum

Polygonaceae

Rhubarb is one of the kitchen garden’s early spring treats. Weeks before the first strawberry ripens, you can enjoy the tart yet sweet flavor of rhubarb’s celerylike red or green leaf stalks in pies, jams, and jellies. ‘Victoria’, ‘Canada Red’, and ‘Valentine’ are three popular varieties that produce red stalks. Don’t eat the foliage, though: It’s poisonous.

Rhubarb needs at least two months of cold weather and does best in areas with 2- to 3-inch-deep ground-freezes and moist, cool springs.

Planting: Grow rhubarb from root divisions, called crowns, rather than from seed, which can produce plants that are not true to type. Three to six plants are plenty for most households.

Choose a sunny, well-drained, out-of-the-way spot for this long-lived perennial. Dig planting holes 3 feet wide and up to 3 feet deep to accommodate the mature roots. Mix the removed soil with generous amounts of aged manure and compost. Refill each hole to within 2 inches of the top, and set one crown in the center of each hole. Top off with the soil mix, tamp down well, and water thoroughly.

Growing guidelines: Once plants sprout, apply mulch to retain soil moisture and smother weeds. Renew mulch when the foliage dies down in fall to protect roots from extremely hard freezes. Provide enough water to keep roots from drying out, even when they’re dormant. Side dress with compost in midsummer and again in fall. Remove flower stalks before they bloom to encourage leaf-stalk production. After several years, when plants become crowded and the leaf stalks are thin, dig up the roots in spring just as they sprout. Divide so that each crown has 1 to 3 eyes (buds); replant.

Problems: Rhubarb is usually pest free. Occasionally it’s attacked by European corn borers and cabbage worms; see page 458 for control ideas. A more likely pest is rhubarb curculio, a ¾-inch-long, rust-colored beetle that you can easily control by hand picking. To destroy its eggs, remove and destroy any nearby wild dock in July.

Diseases are also rare, but rhubarb can succumb to Verticillium wilt, which yellows leaves early in the season and can wilt whole plants in late attacks. Crown rot occurs in shady, soggy soil. For either disease, remove and destroy infected plants; keep stalks thinned to promote good air circulation, and clean up thoroughly around crowns in fall. If stands become seriously diseased, destroy the entire stand. Replant disease-free stock in a new location. ‘MacDonald’ is a rot-resistant variety that grows well in heavy soils.

Harvesting: In spring when the leaves are fully developed, twist and pull stalks from the crowns. Don’t harvest any the first year, though, and take only those that are at least 1 inch thick the second year. By the third year, you can harvest for 1 to 2 months. After the third year, pick all you can eat.

ROCK GARDENS

A rock garden can add natural beauty to a landscape in a way few other gardens can. The best rock gardens start with a natural-looking construction of rocks that is planted with a wide variety of tiny, low-growing plants with colorful flowers.

There are many ways to incorporate a rock garden into your landscape:

Build one on a natural slope, like a steep bank that’s awkward to mow.

Build one on a natural slope, like a steep bank that’s awkward to mow.

Use rocks to build a slope and add interest to a flat yard.

Use rocks to build a slope and add interest to a flat yard.

Design one near a pond.

Design one near a pond.

Use dwarf evergreens or a clump of birches as a background for a rock garden.

Use dwarf evergreens or a clump of birches as a background for a rock garden.

Plant a rock garden on a rock outcrop or in a woodland area.

Plant a rock garden on a rock outcrop or in a woodland area.

Make a raised bed for rock plants edged with stone or landscape ties.

Make a raised bed for rock plants edged with stone or landscape ties.

Design and Construction

A site with full sun or morning sun and dappled afternoon shade is best. If your property is mostly shaded, you still can have a lovely rock garden—choose dwarf, shade-loving perennials, wildflowers, and ferns. Good drainage is an important concern. Most rock garden plants grow best in very well-drained soil high in organic matter—a mixture of equal parts topsoil, humus, and gravel, for example. Plants like moisture about their deep roots but can’t tolerate constantly wet soil.

Stone that is native to your area will look most natural and will be easiest and cheapest to obtain. Stick to one type of rock, repeating the same color and texture throughout to unify the design. Weathered, neutral gray, or tan rocks are ideal. Limestone and sandstone are popular.

If you don’t have enough rocks in your own yard, other good sources are nearby landowners, rockyards, and quarries. Try to pick out the rocks yourself. Choose mostly large, irregular shapes. Be sure to get some large and some mid-sized rocks, but keep in mind you’ll need smaller sizes, too.

Plan your garden before you start moving rocks, although you’ll modify the design as you build. A good way to visualize your plan is to make a 3-D scale model with small stones and sand on a large tray. Mound the sand and arrange your rocks in the model. You might start with a photograph of a favorite mountain scene. Decide how many rocks—and what sizes—you’ll need, and plan for a path or large rock stepping stones for working in the garden and viewing the plants. Keep working until you find a design you like. The key to a successful rock garden—one that is harmonious and natural looking—is studied irregularity.

Plants for Rock Gardens

There are literally hundreds of easy-to-grow rock garden plants. The following are good choices for a garden in full sun.

Dwarf shrubs: Consider dwarf and low-growing forms of evergreens such as false cypresses (Chamaecyparis spp.), junipers (Juniperus spp.), spruces (Picea spp.), pines (Pinus spp.), and hemlocks (Tsuga spp.). Or look for dwarf or creeping barberries (Berberis spp.), cotoneasters (Cotoneaster spp.), and azaleas (Rhododendron spp.).

Perennials: Perennials with evergreen foliage also add winter interest. Consider sedums (Sedum spp.), hens-and-chickens (Sempervivum spp.), and candytuft (Iberis sempervirens). Spring-and summer-blooming perennials include basket-of-gold (Aurinia saxatilis), creeping phlox (Phlox subulata), dwarf bellflowers (Campanula spp.), pinks (Dianthus spp.), catmints (Nepeta spp.), and thymes (Thymus spp.). Windflowers (Anemone spp.), primroses (Primula spp.), and columbines (Aquilegia spp.), are fine choices, too. Consider ferns, hostas, shade-loving wildflowers, and hardy bulbs for a garden in a shady spot. There are many diminutive hardy bulbs for rock gardens in sun or shade, including dwarf daffodils (Narcissus spp.), squills (Scilla spp.), and snowdrops (Galanthus spp.).

Visit local rock gardens—especially in spring—to get ideas about what will grow in your area. The Internet, garden catalogs, books, and magazines are good sources, too. The American Rock Garden Society has an excellent publication, a seed exchange, regional meetings, and also local chapters, many of which hold annual plant sales; see Resources on page 672 for contact information.

To begin construction, mark out the area you’ve selected, remove any weeds or sod, and excavate to a depth of a foot or so. Save the soil for fill. You’ll need extra topsoil for filling in between rocks and building up level areas. If you need to improve drainage, lay in about 8 inches of rubble or small rocks, and cover it with coarse gravel. You may have to remove more soil to accommodate this layer.

You’ll need a garden cart or small dolly to move good-sized rocks, or use iron pipes about 4 inches in diameter as rollers. Use a crowbar for a lever and a block of wood for a fulcrum to position rocks. For massive rocks, a professional with a backhoe might be the answer.

On a flat site, first place large stones on the perimeter to form the garden’s foundation. On a sloping site, place the largest, most attractive rock, the keystone, first. As you work, be sure each rock is stable. Place the wider, heavier part down, and angle rocks to channel water back into the garden. When placing rocks, dig a hole larger than the rock to allow room for moving it into the best position. For the most natural look, lay the rocks so lines in them run horizontally and are parallel throughout the garden.

After positioning each rock, shovel soil around it, ramming it in with a pole so each rock is firmly anchored. Bury a good portion of each rock—two-thirds is traditional—for a natural effect.

Continue adding tiers of rocks in the same manner until you’ve reached the top of the garden. As you work, try to create miniature ridges and valleys and intersperse small, level areas to make an interesting design and provide space for plants. End with a series of flat ledges at different levels rather than a peak.

After you’ve placed all the rocks, shovel soil mix under and around them, making deep planting pockets. A good basic mix is ⅓ topsoil, ⅓ humuslike screened leaf mold, and ⅓ gravel. Tamp it in, wait a week for the soil to settle, and add more to fill to the desired level.

Planting and Care

Plan your planting scheme with tracing paper over a scale drawing of your rock garden, or use labeled sheets of paper and lay out your “plants” right where they’ll grow in the garden. Adjust your design as you visualize it for each season. Record your decisions on paper. Allow low, creeping plants like small bellflowers (Campanula spp.) and thymes (Thymus spp.) to cascade over rocks. Wedge rosette-forming plants such as hens-and-chickens (Sempervivum spp.) into vertical crevices. Fill open spaces with mats of ajuga (Ajuga reptans), pussy-toes (Antennaria spp.), or sedums (Sedum spp.). Use dwarf shrubs to soften the harshness of rocks.

Once planted, all the garden requires in return is faithful weeding, watering during extended droughts, and light pruning. A 1-inch layer of very small pea gravel or granite chips helps conserve moisture, keeps the soil cool, reduces weeds, keeps soil off foliage, and prevents crown rot. Spread the gravel up to, but not over, the crown of each plant. Use chopped leaves to mulch woodland rock gardens.

ROSA

The rose is the best-loved flower of all time, a symbol of beauty and love. Roses have it all—color, fragrance, and great shape. Many roses produce flowers from early summer until frost, often beginning in the year they’re planted. Some also produce showy scarlet or orange fruits called rose hips that are high in vitamin C and are used in teas and jams. Some roses also have ornamental foliage that is reddish, blue-gray, or purple, and some also turn red, orange, or gold in fall.

Over the years, roses have gained a reputation for being difficult to grow. But many of the “old roses,” plus a great number of the newer cultivars, especially the “landscape roses,” are disease-resistant, widely adaptable plants able to withstand cold winters and hot summers.

Selecting Roses

Members of the genus Rosa are prickly-stemmed (thorny) shrubs with a wide range of heights and growth habits. There are as many as 200 species and thousands of cultivars. With so many roses available, deciding on the ones you want can be a challenge. This large, diverse genus can be divided into four major types: bush, climbing, shrub, and groundcover roses.

Bush roses: Bush roses form the largest category, which has been divided into seven subgroups: hybrid tea, polyantha, floribunda, grandiflora, miniature, heritage (old), and tree (standard) roses.

Hybrid tea roses usually have narrow buds, borne singly on a long stem, with large, many-petaled flowers on plants 3 to 5 feet tall. They bloom repeatedly over the entire growing season.

Hybrid tea roses usually have narrow buds, borne singly on a long stem, with large, many-petaled flowers on plants 3 to 5 feet tall. They bloom repeatedly over the entire growing season.

Polyantha roses are short, compact plants with small flowers produced abundantly in large clusters throughout the growing season. Plants are very hardy and easy to grow.

Polyantha roses are short, compact plants with small flowers produced abundantly in large clusters throughout the growing season. Plants are very hardy and easy to grow.

Floribunda roses were derived from crosses between hybrid teas and polyanthas. They are hardy, compact, easily grown plants with medium-sized flowers borne profusely in short-stemmed clusters all summer long.

Floribunda roses were derived from crosses between hybrid teas and polyanthas. They are hardy, compact, easily grown plants with medium-sized flowers borne profusely in short-stemmed clusters all summer long.

Grandiflora roses are usually tall (5 to 6 feet), narrow plants bearing large flowers in long-stemmed clusters from summer through fall.

Grandiflora roses are usually tall (5 to 6 feet), narrow plants bearing large flowers in long-stemmed clusters from summer through fall.

Miniature roses are diminutive, with both flowers and foliage proportionately smaller. Most are quite hardy and bloom freely and repeatedly.

Miniature roses are diminutive, with both flowers and foliage proportionately smaller. Most are quite hardy and bloom freely and repeatedly.

Heritage (old) roses are a widely diverse group of cultivars developed prior to 1867, the date of the introduction of the hybrid tea rose. Plant and flower forms, hardiness, and ease of growth vary considerably; some bloom only once, while others flower repeatedly. Among the most popular are the albas, bourbons, centifolias, damasks, gallicas, mosses, and Portlands. Some species roses are also included in this category.

Heritage (old) roses are a widely diverse group of cultivars developed prior to 1867, the date of the introduction of the hybrid tea rose. Plant and flower forms, hardiness, and ease of growth vary considerably; some bloom only once, while others flower repeatedly. Among the most popular are the albas, bourbons, centifolias, damasks, gallicas, mosses, and Portlands. Some species roses are also included in this category.

Tree (standard) roses are created when any rose is bud-grafted onto a specially grown trunk 1 to 6 feet tall to form a “tree” shape.

Tree (standard) roses are created when any rose is bud-grafted onto a specially grown trunk 1 to 6 feet tall to form a “tree” shape.

Climbing roses: Roses don’t truly climb, but the long, flexible canes of certain roses make it possible to attach them to supports such as fences, posts, arbors, and trellises. The two main types are large-flowered climbers, with thick, sturdy canes growing to 10 feet long and blooms produced throughout summer, and ramblers, with thin canes growing 20 feet or more and clusters of small flowers borne in early summer.

Shrub roses: Shrub roses grow broadly upright with numerous arching canes reaching 4 to 12 feet tall. Most are very hardy and easily grown. Some only bloom once in early summer, while others bloom repeatedly. Many produce showy red or scarlet fruits called hips. Some species roses are considered shrub roses.

Groundcover roses: Groundcover roses have prostrate, creeping canes producing low mounds; there are once-blooming and repeat-blooming cultivars.

Landscape roses: Groundcover roses are sometimes included with easy-care shrub roses in a category called “landscape roses” that are renowned for toughness and low maintenance. Roses like the ‘Knockout’, ‘Carefree’, and ‘Simplicity’ series of shrub roses and the ‘Flower Carpet’ and ‘Blanket’ series of groundcovers, as well as individual cultivars like ‘Bonica’ and the award-winning floribunda rose ‘Livin’ Easy’, are disease resistant, long blooming, and require minimal pruning. They’re a great choice if you’d like the beauty of roses in your landscape without the fussiness of many hybrid teas.

Using Roses in the Landscape

To grow well, roses need a site that gets full sun at least 6 hours a day, humus-rich soil, and good drainage. If these conditions are met, you can use roses just about anywhere in the landscape. Try roses in foundation plantings, shrub borders, along walks and driveways, surrounding patios, decks, and terraces, or in flower beds and borders. Combine roses with other plants, especially other shrubs, perennials, and ornamental herbs, and try planting them in containers too.

All-America Rose Selections

For roses that are guaranteed to thrive in your garden, look for the AARS seal. All-America Rose Selections is a nonprofit organization of rose breeders and growers dedicated to evaluating roses and selecting the ones that thrive with no more than typical garden care across all regions of the country. AARS has been evaluating roses and giving the winners the AARS seal of approval since 1938. Roses are evaluated on such characteristics as vigor and disease resistance as well as flower production and form, fragrance, growth habit, and foliage. AARS has 20 trial gardens across the country to ensure that winning roses can thrive across a wide spectrum of conditions. Go to www.rose.org to find a list of all AARS winners as well as Region’s Choice winners that are best adapted to your own region.

Use climbing roses to cover walls, screen or frame views, or decorate fences, arbors, trellises, and gazebos. Grow groundcover roses on banks or trailing over walls. Plant hedges of shrub, grandiflora, and floribunda roses.

Growing Good Roses

The key to growing roses is to remember they need plenty of water, humus, and nutrients.

Soil: Prepare a new site in fall for planting the following spring, or in summer for fall planting. If you plan to grow roses in an existing planting, then no special preparation is needed. For a new site, dig or till the soil to a depth of at least 1 foot. Evenly distribute a 4-inch layer of organic material such as compost, leaf mold, or dehydrated cow manure over the soil surface. Also spread on organic fertilizer. A general recommendation is to add 5 pounds of bonemeal and 10 pounds of greensand or granite dust per 100 square feet. Dig or till the fertilizer and soil amendments into the soil.

Planting: For much of the West Coast, South, and Southwest, or wherever winter temperatures remain above 10°F, plant bareroot roses in January and February. In slightly colder areas, fall planting gives roses a chance to establish a sturdy root system before growth starts. In areas with very cold winters, plant bareroot roses in spring, several weeks before the last frost. For all but miniature and shrub roses, space roses 2 to 3 feet apart in colder areas, 3 to 4 feet apart in warmer regions, where they’ll grow larger. Space miniatures 1 to 2 feet apart, shrub roses 4 to 6 feet apart.

To plant bareroot roses, dig each hole 15 to 18 inches wide and deep, or large enough for roots to spread out. Form a soil cone in the planting hole. Removing any broken or damaged roots or canes, position the rose on the cone, spreading out the roots. If you are planting a grafted rose, place the bud union (the point where the cultivar is grafted onto its rootstock) even with the soil surface in mild climates and 1 to 2 inches below the soil surface in areas where temperatures fall below freezing.

SMART SHOPPING

Roses

Whether they’re sold locally or by mail order, roses are sold by grade, which is based on the size and number of canes. Top-grade #1 plants grow fastest and produce the most blooms when young. The #1½-grade plants are also healthy and vigorous. Avoid #2-grade plants, which require extra care. Rose grades are usually listed only for bareroot roses, while container-grown roses are typically listed by the size of the container (for example, 3 gallons).

You can buy either dormant, bareroot roses or container-grown plants. Both mail-order companies and local outlets sell dormant plants, offering the widest range of cultivars. Healthy dormant plants have smooth, plump, green or red canes. Avoid plants with dried out, shriveled, wrinkled, or sprouted canes.

One excellent resource for information about roses is the American Rose Society, which publishes the Handbook for Selecting Roses, updated every year, with a listing of rose cultivars rated for quality. Another is the Combined Rose List, which lists all roses available, with their sources; it is also updated annually. To learn more about both publications, see Resources on page 672.

Add soil around the roots, making sure there are no air pockets, until the hole is ¾ full. Fill the hole with water, allow it to soak in, and refill. Make sure the bud union is at the correct level. Finish filling the hole with soil and lightly tamp it down. Trim canes back to 8 inches, making cuts ¼ inch above an outward-facing bud and at a 45° angle. To prevent the canes from drying out, lightly mound moist soil over the rose bush. Gently remove the soil when growth starts in 1 to 2 weeks.

Plant container-grown roses as you would any container plant. For more on this technique, see the Planting entry.

Water: Ample water, combined with good drainage, is fundamental to rose growth. The key is to water slowly and deeply, soaking the ground at least 16 inches deep with each watering. Water in the early morning, so if foliage gets wet, it can dry quickly. Use a soaker hose, drip irrigation system, or a hose with a bubbler attachment on the end. Water roses grown in containers much more frequently. Check containers daily during summer.

Mulch: An organic mulch conserves moisture, improves the garden’s appearance, inhibits weed growth, keeps the soil cool, and slowly adds nutrients to the soil. Spread 2 to 4 inches of mulch evenly around the plants, leaving several inches unmulched around the stem of each rose.

Fertilizing: Feed newly planted roses 4 to 6 weeks after planting. After that, for roses that bloom once a year, fertilize in early spring. Feed established, repeat-blooming roses three times a year: in early spring just as the growth starts, in early summer when flower buds have formed, and about 6 weeks before the first fall frost. The last feeding should not contain nitrogen.

For all but the last feeding in fall, use a commercial, balanced organic plant food containing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, or mix your own, combining 2 parts blood meal, 1 part rock phosphate, and 4 parts wood ashes for a 4–5–4 fertilizer. This mix, minus the blood meal, also works well as a fall fertilizer. Use about ½ cup for each plant, scratching it into the soil around the plant and watering well. As an alternative, apply dehydrated cow manure and bonemeal in spring and use fish emulsion for the other feedings.

Pruning: Prune in early spring to keep hybrid tea, grandiflora, and floribunda roses vigorous and blooming. Many of the newer, shrub-type (“landscape”) roses need very little pruning; simply remove dead canes and any canes that are growing where you don’t want them. Heritage, species, and climbing roses that bloom once a year bear flowers on the previous year’s growth. Prune these as soon as blooming is over, cutting the main shoots back ⅓ and removing any small, twiggy growth. Remove suckers coming up from the rootstock of any grafted rose whenever you see them.

In the first pruning of the season, just as growth starts, remove any dead or damaged wood back to healthy, white-centered wood. Make each pruning cut at an angle ¼ inch above an outward-facing bud eye, which is a dormant growing point at the base of a leaf stalk. This stimulates outward-facing new growth. Also remove any weak or crossing canes. Later in the season, remove any diseased growth and faded flowers on repeat-blooming roses, cutting the stem just above the first five-leaflet leaf below the flower.

Winter protection: Most landscape roses and many shrub roses as well as some of the polyanthas, floribundas, and miniatures need only minimal winter protection. Hybrid teas, grandifloras, and some floribundas and heritage roses usually require more. If you’re growing these cold-sensitive plants in your garden, protect them according to the following recommendations.

In areas with winter temperatures no lower than 20°F, no winter protection is necessary. Elsewhere, apply winter protection after the first frost and just before the first hard freeze. Remove all leaves from the plants and from the ground around them and destroy them. Apply ¼ cup of greensand around each plant and water well. Prune plants to ½ their height and tie canes together with twine.

Where winter temperatures drop to 0°F, make an 8-inch mound of coarse compost, shredded bark, leaves, or soil around the base of each plant. In colder areas, make the mound 1 foot deep. Provide extra protection with another layer of pine needles or branches, straw, or leaves. Where temperatures reach –5°F or colder, remove the canes of large-flowered, repeat-blooming climbers from supports, lay them on the ground, and cover both the base and the canes.

Rose Pests and Diseases

Your best defense against rose problems is to buy healthy, disease-resistant roses and to plant them where there’s good air circulation. Be diligent about preventive maintenance, such as destroying diseased foliage and flowers immediately and cleaning up around roses in fall. Control pests as soon as you see them. If a rose suffers from repeated pest or disease problems, your best course of action is to get rid of that rose and try another—preferably a disease-resistant variety.

These are the rose pests and diseases you’re most likely to encounter:

Aphids: These tiny insects cluster on new growth, causing deformed or stunted leaves and covering buds with sticky residue. Control with a strong blast of water or spray with insecticidal soap.

Borers: Larvae of rose stem girdler, rose stem sawfly, or carpenter bees bore holes in rose canes; new growth wilts. Prune off damaged canes and seal ends with putty, paraffin, or nail polish.

Japanese beetles: Hand pick beetles every day while they’re in the area and drop them in a bucket of soapy water. Spray roses with neem oil to deter beetle feeding. For more control tips, see page 459.

Spider mites: These tiny spiderlike creatures cause yellowed, curled leaves with fine webs on the undersides. Spray in early morning with a strong jet of water for 3 days, or use insecticidal soap. Be sure to spray the undersides of the leaves.

Blackspot: This fungal disease causes black spots and yellowed leaves; defoliation is worst during wet weather. Prune off all damaged plant parts, don’t splash foliage when watering, water in the morning, and spray every 10 to 14 days with neem oil, with fungicidal soap, or a bicarbonate fungicide. Avoid problems by choosing blackspot-resistant roses.

Powdery mildew: This coating of white powder on leaves, stems, and buds is worst in hot, humid (but not wet) weather with cool nights. Provide good air circulation; prune off infected plant parts; and treat with fungicidal soap or neem oil.

Rust: This disease causes red-orange spots on the undersides of leaves and yellow blotches on top surfaces. Prune off infected plant parts; spray with fungicidal soap or neem oil.

ROW COVERS

It is the rare gardener who finds the growing season long enough. Fortunately, gardeners can satisfy the itch to plant early and to keep crops producing through fall by using row covers. Made of light, permeable material, usually polypropylene or polyester, row covers can be laid loosely on top of plants or supported with wire hoops. They’re available in different weights that provide varying degrees of frost protection.

Floating row cover: The lightest-weight row covers, also called floating row covers, allow air, water, and up to 85 percent of ambient light to pass through. They provide only a few degrees of frost protection, but they are an excellent barrier against damage by a wide range of pests.

You can cover newly seeded beds or pest-free transplants with floating row covers, leaving plenty of slack in the material to allow for growth. Be sure to bury the edges in the soil or seal them in some other way. Otherwise, pests will sneak in and thrive in the protected environment.

You can leave row covers over some crops, such as carrots or onions, all season. Uncover other crops, such as beans or cabbage, once the plants are well grown or the generation of pests is past. Plants such as squash that require pollination by insects must be either uncovered when they start to flower or hand pollinated. In a hot climate you may have to remove covers to prevent excessive heat buildup.

Heavier covers: Gardeners can also use heavier row covers to protect plants from freezing and extend the gardening season. These row covers can provide as much as 8 degrees of frost protection. They also block more light, so plants underneath them may not grow as quickly. Or, you can get a similar effect to heavy covers by using two layers of a lighter-weight cover.

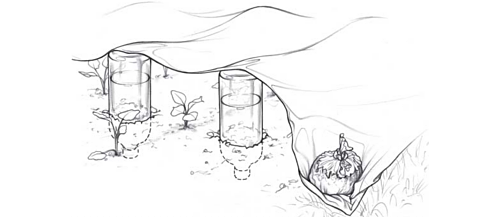

Supporting row covers. If you don’t want to fuss with wire hoops to support row covers, use plastic soda bottles as “tent poles” instead. Put some water in each bottle, cap it tightly, and upend the bottles between rows of plants to support the cover above the foliage.

Plastic row covers: Row covers made of plastic or slitted plastic require careful management because temperatures under plastic row covers can be as much as 30°F higher than the surrounding air. You will need to vent them on warm days and close them back up at night. Slitted plastic row covers don’t require venting. Colored or shaded plastic covers are available for Southern gardeners. The coloring blocks out some of the sunlight, reducing the heat inside the tunnel. Suspend plastic row covers over the row with metal, plastic, wire, or wooden hoops to prevent injuring plants. Anchor row cover edges securely in place with soil, boards, pipes, or similar material.

Handling Row Covers

Working with fabric row covers may seem awkward at first, because the lightweight fabric tends to blow around while you’re putting it in place if there’s even a small breeze. The fabric also tears easily on sharp edges. But with a little experience, you’ll learn how to work with the material. Here are some tips for getting the best from row covers:

Row covers are available in small pieces that are easy to manage, but it’s more economical to buy a larger roll and cut pieces to fit as you need them.

Row covers are available in small pieces that are easy to manage, but it’s more economical to buy a larger roll and cut pieces to fit as you need them.

The quick and easy way to anchor row cover is with rocks or soil, but this also tends to tear the fabric quickly. Instead, try using plastic soda bottles partially filled with water as weights, or make “sandbags” by filling plastic shopping bags partway with soil.

The quick and easy way to anchor row cover is with rocks or soil, but this also tends to tear the fabric quickly. Instead, try using plastic soda bottles partially filled with water as weights, or make “sandbags” by filling plastic shopping bags partway with soil.

Wire hoops, which you can buy from garden suppliers or make yourself from 9-gauge wire, are perfect for supporting row covers over garden beds. Use hoops both under and over the fabric to hold it in place.

Wire hoops, which you can buy from garden suppliers or make yourself from 9-gauge wire, are perfect for supporting row covers over garden beds. Use hoops both under and over the fabric to hold it in place.

At the end of the season, shake the covers to loosen dirt and debris, and make sure they’re dry. Fold or roll them and store them in a plastic storage bind for winter, either in a garden shed or outdoors. Weight the cover of the tub with rocks or bricks to keep it tightly closed.

At the end of the season, shake the covers to loosen dirt and debris, and make sure they’re dry. Fold or roll them and store them in a plastic storage bind for winter, either in a garden shed or outdoors. Weight the cover of the tub with rocks or bricks to keep it tightly closed.

If a piece of row cover is torn in several places, cut it up into small pieces for patching larger sections of cover that have small holes. Waxed dental floss works well for “sewing” the patches.

If a piece of row cover is torn in several places, cut it up into small pieces for patching larger sections of cover that have small holes. Waxed dental floss works well for “sewing” the patches.

To protect upright plants with row cover, put a small tomato cage in place around the plant and wrap row cover fabric around the cage, pinning it in place with clothespins.

To protect upright plants with row cover, put a small tomato cage in place around the plant and wrap row cover fabric around the cage, pinning it in place with clothespins.

RUDBECKIA

Coneflower, black-eyed Susan. Summer-blooming annuals and perennials.

Description: Summer-blooming annual Rudbeckia hirta, black-eyed Susan, bears single yellow, dark-centered daisies on 3-foot stems. The beloved cottage and cutting garden staples, Gloriosa daisies, with their marvelous blends of gold, orange, reddish, and mahogany petals on daisies up to 6 inches across, are a strain of this species; like black-eyed Susans, they bloom the first year from seed and are usually treated as annuals, though they may live a second or even third year if left in place.

Perennial R. fulgida, orange coneflower, bears 3- to 4-inch single, dark-centered gold daisies on 1½- to 3-foot plants in late summer and autumn. R. fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’ is a widely grown, very floriferous cultivar, often grown from seed. Zones 3–9.

How to grow: Coneflowers need a sunny spot with average to rich, well-drained soil. Sow annuals indoors in spring to set out after frost. Plant perennials in spring or fall. Divide every 3 to 4 years; deadhead to avoid self-seeding unless you want them to spread in a meadow or prairie garden. Mildew can be an issue on the foliage, so avoid overhead watering and don’t crowd the plants.

Landscape uses: Mass in borders with other summer bloomers, in informal plantings, and cutting gardens. Coneflowers are naturals for the meadow or prairie garden, where their showy blooms add welcome color. Leave them standing in the meadow or prairie until spring—birds (including goldfinches) love the seeds, and the cones will remain showy through winter.

RUTABAGA

See Turnip