ULMUS

Elm. Deciduous trees.

Description: Ulmus alata, winged elm, has a pyramidal form and is 30 to 40 feet tall. It flowers inconspicuously in spring and bears small, fuzzy, waferlike fruits. The small (2½-inch) leaves turn soft reds and oranges in fall most years. Thin twigs sport corky wings. This Southeastern native elm can be weedy and is considered undesirable by some, but it grows beautifully in poor, compacted soils. Zones 6–8.

U. americana, American elm, is the stately 60- to 80-foot, vase-shaped tree that for many years shaded North American campuses and avenues. Much publicized in the wake of the Dutch elm disease (DED) epidemic that decimated huge numbers of this species, American elm is a beautiful, but no longer recommended, shade tree. Zones 2–8.

U. parvifolia, Chinese, or lacebark elm, is a handsome tree with flaking bark that exposes patches of tan, green, and cream. Growing 40 to 50 feet, Chinese elm has inconspicuous, late-summer flowers and small (1- to 3-inch) leaves that turn yellow or purple shades when conditions favor good autumn color development. Zones 5–8.

U. pumila, Siberian elm, is a fast-growing, weak-wooded tree with few assets beyond its hardiness and ability to grow on very poor sites. It has an irregular, open form and a landscape height of 50 to 70 feet. During dormancy, Siberian elm’s round black buds distinguish it from the highly desirable Chinese elm, which has relatively flat buds. Zones 2–8.

How to grow: Elms are adapted to a variety of soil types but require good drainage and full sun. While many American elms still stand, far more have fallen to DED. Control programs are somewhat effective, but until DED is controlled, admire American elms, but don’t plant them. Breeding programs continue to search for DED-resistant American elm cultivars, often crossing it with Asian elm species. No reliably resistant trees have yet been selected that have American elm’s desirable features.

Elm leaf beetles will feed on all elms, but seem to prefer Siberian elm. The ½-inch-long adults are drab yellow-green, black-striped beetles that eat round holes in young elm leaves in spring, then lay eggs that hatch into leaf-skeletonizing larvae. The result is an unhealthy-looking tree with brown foliage. Elms often respond with another flush of growth just in time for the next generation of beetles. Adults also overwinter in nearby buildings. Spray Btsd (Bacillus thuringiensis var. san diego) after eggs hatch (late May through June) to control larvae.

Landscape uses: Naturalize winged elm among other trees. Use Chinese elm for shade and as a focal point, much as you would American elm. Plant Siberian elm hybrids on difficult sites.

URBAN GARDENING

Urban gardeners face different challenges than their rural and suburban counterparts. It can take ingenuity and determination to garden in small city lots where neighboring buildings block the sunlight, the soil quality may be dreadful, and water sources unreliable. Soil and air pollutants, theft, vandalism, and politics further complicate city gardening.

There are some benefits to city gardening too—no pesky deer or other wildlife to eat the flowers and fruits is one. Another benefit is a frost-free season as much as one month longer than that in surrounding areas, due to the warming effects of buildings and pavement. Easily managed smaller gardens demand less time but inspire creativity in the quest for productive beauty. City farmers turn yards, rooftops, fire escapes, and a variety of containers into fields of plants.

In 1976, Congress established urban gardening programs through the Cooperative Extension Service. The not-for-profit American Community Gardening Association (ACGA) also promotes gardening nationwide. See the Community Gardens entry for more information on ACGA programs.

Urban Concerns

The key to city gardening success is adapting traditional gardening methods to suit the limits imposed by an urban environment.

Space: Design your garden to maximize growing area while preserving living space. Make the most of your garden space by growing compact (bush-type) cultivars. Use containers to maximize your gardening potential. To utilize vertical space, build trellises or fences for vines. See the Container Gardening and Trellising entries for more information on these techniques.

Light: Select plants and a design to suit each location, based on the total light it receives. Most edible plants need at least 6 hours of daily sunlight to produce flowers and fruits.

Soil: In general, urban soils are compacted and clayey, and they tend to have a high heavy-metal content. Improve such soils by adding compost, aged sawdust, or other types of organic matter. Many cities make compost or mulch from tree trimmings and leaf pickups. Contact local parks or street departments about these often-free soil amendments.

Some urban lots have no soil, or soil that’s so poor it can’t quickly be improved. An alternative to amending existing soil is to bring in soil for raised beds or containers.

Theft and vandalism: Most urban gardening takes place in densely populated or publicly accessible places. Theft and vandalism can be a frustrating reality. Fences keep honest people honest, but involving area youth and adults in gardening is a more effective tactic. Share garden space and/or knowledge with your neighbors.

To reduce vandalism and theft, keep your garden well maintained, repair damage immediately, harvest ripened vegetables daily, and plant more vegetables than you need. Grow ornamentals in the garden to hide ripening vegetables.

Soil contaminants: Excessive lead, cadmium, and mercury levels are common in urban soils. Sources of such pollution include leaded paint, motor vehicle exhaust, and industrial waste. Poisoning from eating contaminated produce can affect all gardeners, especially young children whose bodies are actively growing and who tend to put their hands in their mouths.

You can reduce the amount of lead that plants absorb from soil and also keep down dust that may carry lead by adding organic matter to soil and mulching heavily. Planting food crops away from streets and keeping soil pH levels at 6.7 or higher will also help prevent plants from taking up lead. If contaminant levels are too high, garden in containers filled with clean soil and wash crops thoroughly before eating them.

Testing to monitor soil contaminants is strongly urged for city gardens, particularly those used by children. Contact your local extension service office to find out what soil tests are available.

VEGETABLE GARDENING

Fresh-picked sweet corn and snap peas are a taste treat you can get only from your backyard vegetable garden. The quality and flavor of fresh vegetables will reward you from early in the growing season until late fall. And when you garden organically, your harvest will be free of potentially harmful chemical residues. Plus, vegetables you grow yourself are free of the “food mile” cost to the environment of growing produce in one region of the country (or the world) and shipping it to another.

Although the plants we grow in our vegetable gardens are a diverse group from many different plant families, they share broad general requirements. Most will thrive in a garden that has well-drained soil with a pH of 6.5 to 7.0 and plenty of direct sun. Some crops can tolerate frost; others tolerate some shade. If you pick an appropriate site, prepare the soil well, and keep your growing crops weeded and watered, you should have little trouble growing vegetables successfully.

This entry will serve as your guide to planning, preparing, and tending your vegetable plot through the seasons. Throughout, you’ll find references to the many other entries that provide detailed information on topics such as soil improvement and pest control that you’ll find helpful.

Planning Your Garden

Planning your garden can be as much fun as planting it. When you plan a garden, you’ll balance all your hopes and wishes for the crops you’d like to harvest against your local growing conditions, as well as the space you have available. Planning involves choosing a site (unless you already have an established garden), deciding on a garden style, selecting crops and cultivars, and mapping your garden.

Site Selection

Somewhere in your yard, there is a good place for a vegetable garden. The ideal site has these characteristics:

- Full or almost full sun. In warm climates, some vegetables can get by on 6 hours of direct sunshine each day, while a full day of sun is needed in cool climates. The best sites for vegetable gardens usually are on the south or west side of a house.

- Good drainage. A slight slope is good for vegetable gardens. The soil will get well soaked by rain or irrigation water, and excess will run off. Avoid low places where water accumulates; these are ideal breeding places for diseases.

- Limited competition. Tree roots take up huge amounts of water. Leave as much space as possible between large trees and your garden. Plant shade-tolerant shrubs or small fruits between trees and your garden.

- Easy access to water. If you can’t run a hose or irrigation line to a prospective garden site, don’t plant vegetables there. No matter what your local climate is, you’ll most likely have to provide supplemental water at some point in the growing season.

- Accessibility. Organic gardens need large amounts of mulch, plus periodic infusions of other bulky materials such as compost or rock fertilizers. If you have a large garden, try to leave access for a truck to drive up to its edge for easy unloading. In narrow city lots, the garden access path should be wide enough for a cart or wheelbarrow.

Once you find a site that has these characteristics, double-check for hidden problems. For example, don’t locate your garden over septic-tank field lines, buried utility cables, or water lines.

Garden Layout

Once you’ve decided on a site, think about the type of vegetable garden you want. Raised beds offer lots of advantages, and old-fashioned rows work well for some crops. Containers are a great choice for small or shady yards.

Raised beds: Productivity, efficient use of space, less weeding, and shading the soil are all benefits of intensively planted beds. Beds are raised planting areas, generally with carefully enriched soil, so they can be planted intensively, with crops spaced close together. While they require more initial time to prepare, beds save time on weeding or mulching later in the season. Because they’re more space efficient, you’ll also get higher yields per area than from a traditional row garden.

Beds for vegetables should be no more than 4 feet wide so you can easily reach the center of the bed to plant, weed, and harvest. See the Raised Bed Gardening entry for directions on making raised beds.

Row planting: A row garden, in which vegetables are planted in parallel lines, is easy to organize and plant. However, it’s not as space efficient as a raised bed garden, so you’ll reap less of a yield per square foot. You also may spend more time weeding unless you mulch heavily and early between rows.

Row planting is quick and efficient for large plantings of crops such as beans or corn. You may decide to plant some crops in rows and others in beds. “Sod Strips Save Work” describes an easy way to start a row garden.

Sod Strips Save Work

When transforming a plot of lawn into a vegetable garden, try cultivating strips or beds in the sod. You’ll only have to contend with weeds in the beds. Plus, you’ll have excellent erosion control and no mud between the rows, which makes picking easier and more enjoyable.

Tilling the bed: Overlap your tilling so that the finished bed is 1½ to 2 times the cutting width of your tiller. Start out with a slow wheel speed and shallow tilling depth. Gradually increase speed and depth as the sod becomes more and more workable. Make the beds as long or as short as you want, but space the beds about 3 feet apart and leave sod between them. Depending on how tough the sod and your tiller are, you may have to retill the beds in a week or two or hand dig stubborn grass clumps to make a proper seedbed. On your final pass, first spread 1 to 2 inches of rich compost over the soil surface. This will help your soil to recover from the detrimental impact of tilling, and will also provide nutrients for your crops.

Weed control: You can control weeds easily in the rows with a wheel-hoe cultivator or hand hoe or by hand weeding. What about weeds along the outside edges of the beds? Just mow them down with your lawnmower when you mow the grassy areas between the beds. You’ll be rewarded with a ready supply of grass clippings for compost or mulch.

Caution: Before mowing, be sure to pick up all of the larger rocks that your tiller brought to the surface. Rocks will quickly dull and chip your mower blade, and they’re downright dangerous to people, pets, and property when your mower kicks them up and hurls them through the air.

Once your garden is finished for the season, sow a cover or green manure crop such as buckwheat, clover, or ryegrass in the beds. The following spring, just till the strips that were in sod. They’ll become your planting beds, and the previous year’s beds will be pathways. It’s crop rotation made easy!

You can also let your sod strips be permanent pathways. Either way, after the initial tilling, you should never need to use your tiller to prepare the soil again. Simply add more organic matter yearly through cover cropping and mulching and work it in lightly with hand tools, or plant directly through the surface cover.

Spot gardens: If your yard is small, having no suitable space for a separate vegetable garden, look for sunny spots where you can fit small plantings of your favorite crops. Plant a small bed of salad greens and herbs near your kitchen door for easy access when preparing meals. Tuck vegetables into flower beds. You can dress up crops that aren’t ornamental, such as tomatoes, by underplanting them with annuals such as nasturtiums and marigolds. For ideas on incorporating vegetables into your landscape, see the Edible Landscaping entry.

Small-Garden Strategies

If your appetite for fresh vegetables is bigger than the space you have to grow them in, try these ways to coax the most produce from the least space:

- Emphasize vertical crops that grow up rather than out: trellis snow peas, shell peas, pole beans, and cucumbers.

- Interplant fast-maturing salad crops (lettuce, radishes, spinach, and beets) together in 2-foot-square blocks. Succession plant every 2 weeks in early spring and early fall.

- Avoid overplanting any single vegetable. Summer squash is the number one offender when it comes to rampant overproduction. Two plants each of zucchini, yellow-neck, and a novelty summer squash will yield plenty.

- Choose medium- and small-fruited cultivars of tomatoes and peppers. The smaller the fruits, the more the plants tend to produce. Beefsteak tomatoes and big bell peppers produce comparatively few fruits per plant.

- Experiment with unusual vegetables that are naturally compact—such as kohlrabi, bok choy, and Oriental eggplant—and with dwarf varieties of larger vegetables.

- Maintain permanent clumps of perennial vegetables such as hardy scallions, and perennial herbs such as chives. Even a small garden should always have something to offer.

Containers: You may not be able to grow all your favorite vegetables in containers, but many dwarf cultivars of vegetables will grow well in pots or planters. Garden catalogs include dwarf tomato, cucumber, pea, pepper, and even squash cultivars suitable for container growing. Vegetables that are naturally small, such as leaf lettuce, scallions, and many herbs, also grow nicely in containers. See the Container Gardening entry for details on choices of containers and soil mixes.

Crop Choices

Generally, vegetables can be divided into cool-weather, warm-weather, and hot-weather crops, as shown on page 608.

Consider the length of your growing season (the period of time between the last frost in spring and the first one in fall), seasonal rainfall patterns, and other environmental factors when choosing vegetables. Fast-maturing and heat- or cold-tolerant cultivars make it easier for Northern gardeners to grow hot-weather crops such as melons and okra, and for Southern gardeners to be able to enjoy cool-loving crops such as spinach and lettuce. See page 603 for more ideas on how to make good crop and cultivar choices for your garden.

Some Like It Hot

Because vegetables differ so much in their preferred growing temperatures, planting the vegetable garden isn’t a one-day job. Be prepared to spend several days over the course of early spring to early summer planting vegetable seeds and plants. You’ll start planting cool-weather crops a few weeks before the last spring frost, and continue making small seedings every couple of weeks. Set out warm-weather crops just after the last spring frost. Hot-weather crops cannot tolerate frost or cold soil. Unless you can protect them with a portable cold frame or row covers, plant them at least 3 weeks after the last spring frost. In warm climates, plant cool-weather crops again in early fall so that they grow during fall and winter. Here is a guide to the temperature preferences of 30 common garden vegetables.

| Cool Weathe | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beets | Cauliflower | Lettuce | Spinach |

| Broccoli | Celery | Onions | Turnips |

| Cabbage | Garden peas | Radishes | |

| Warm Weather | |||

| Cantaloupes | Corn | Potatoes | Squash |

| Carrots | Cucumbers | Pumpkins | Tomatoes |

| Chard, Swiss | Peppers | Snap beans | |

| Hot Weather | |||

| Eggplant | Lima beans | Peanuts | Sweet potatoes |

| Field peas | Okra | Shell beans | Watermelons |

Make some of your selections for beauty as well as flavor. Beans with purple or variegated pods are easy to spot for picking and lovely to behold. Swiss chard with red ribs makes a dramatic statement, and purple kohlrabi is oddly eye-catching. Small-fruited Japanese eggplants look elegant in an attractive container. Try some historical heirlooms or little-known imports. Cultivars endorsed by All-American Selections (AAS) also are good bets. For more details, refer to the Heirloom Plants and All-America Selections entries.

Garden Mapping

As you fill in seed order forms, it’s wise to map planned locations for your crops. Otherwise, you may end up with far too little or too much seed. Depending on the size of your garden, you may need to make a formal plan drawn to scale.

Consider these points as you figure out your planting needs and fill in your map:

Are you growing just enough of a crop for fresh eating, or will you be preserving some of your harvest? For some crops, it takes surprisingly little seed to produce enough to feed a family. You can refer to seed catalogs or check individual vegetable entries for information on how much to plant.

Are you growing just enough of a crop for fresh eating, or will you be preserving some of your harvest? For some crops, it takes surprisingly little seed to produce enough to feed a family. You can refer to seed catalogs or check individual vegetable entries for information on how much to plant.

Are you planning to rotate crops? Changing the position of plants in different crop families from year to year can help reduce pest problems.

Are you planning to rotate crops? Changing the position of plants in different crop families from year to year can help reduce pest problems.

Are you going to plant crops in spring and again later in the season for a fall harvest? Order seed for both plantings at the same time.

Are you going to plant crops in spring and again later in the season for a fall harvest? Order seed for both plantings at the same time.

SMART SHOPPING

Making the Right Choices

Seed catalogs and seed racks present a dazzling array of choices for the vegetable gardener. They all look tasty and beautiful in the pictures, but here’s how to choose:

- If you’re a beginning gardener, talk with other gardeners and your local extension agent. Ask what vegetables grow best in your area, and start with those crops. Most extension service offices also provide lists of recommended cultivars.

- Seek out catalogs and plant lists offered by seed companies that specialize in regionally adapted selections.

- Match cultivars to your garden’s characteristics and problems. Look for cultivars that are resistant to disease organisms that may be widespread in your area, such as VF tomato cultivars—which are resistant to Verticillium and Fusarium fungi.

- If you buy seeds by the packet, take note of how many seeds you’re getting. Seed quantity per packet varies widely. Some packets of new or special cultivars may contain fewer than 20 seeds. Consider buying a half ounce or ounce of seeds and then dividing them up with gardening friends.

- When buying transplants at local garden centers, always check plants for disease and insect problems. Don’t forget to check roots as well as leaves.

- Ask whether the transplants you’re buying have been hardened off yet. If the salesperson doesn’t know what you’re talking about, take the hint, and buy your transplants from a more knowledgeable supplier.

- Remember, with transplants, larger size doesn’t always mean better quality. Look for stocky transplants with uniform green leaves. Avoid buying transplants that are already flowering—they won’t survive the shock of transplanting as well as younger plants will.

Preparing the Soil

Since most vegetables are fast-growing annuals, they need garden soil that provides a wide range of plant nutrients and loose soil that plant roots can penetrate easily. Every year when you harvest vegetables, you’re carting off part of the reservoir of nutrients that was in your vegetable garden soil. To keep the soil in balance, you need to replace those nutrients. Fortunately, since you’re working the soil each year, you’ll have lots of opportunities to add organic matter and soil amendments that keep your soil naturally balanced.

If you’re starting a new vegetable garden or switching from conventional to organic methods (or if you’ve just been disappointed with past yields or crop quality), start by testing your soil. Soil acidity or alkalinity, which is measured as soil pH, can affect plant performance and yield, especially for heavy-feeding crops such as broccoli and tomatoes. A soil test will reveal soil pH as well as any nutrient imbalances. See the Soil entry for details on soil testing, and the pH and Fertilizers entries for more on providing ideal conditions for your plants.

New Gardens

If you’re just starting out, using a rotary tiller may be the only practical way to work up the soil in a large garden. But whether you’re working with a machine or digging by hand, don’t turn the soil when it’s too wet or too dry. It will have serious detrimental effects on soil structure and quality. You’ll find more information on preparing new garden beds in the Soil entry, including how to tell whether soil is ready to work. See “Sod Strips Save Work” on page 619 for a simple method for creating a new garden in a lawn area and the Raised Beds entry for another excellent approach to creating rich, fertile soil for a vegetable garden.

Baby Vegetables

Baby carrots have become a staple in grocery stores, but there are other easy-to-grow baby vegetables. Some, like leeks, cauliflower, onions, lettuce, and other greens are produced by a combination of close spacing and early harvest. Sow seed close together and harvest as soon as the plants are large enough. To produce baby summer squash, give plants normal spacing, but harvest when the fruit is still quite small and tender. Full-size cherry tomato plants naturally produce small fruit, although you can also find dwarf plants. Fingerling potatoes also are naturally small.

To produce other baby vegetables, start with cultivars specially designed for that purpose. Look at vegetable seed catalogs or specialty Internet sites for seed for baby carrots, beets, petite pois peas, filet beans, and eggplant.

Depending on the results of your soil tests, you may need to work in lime to correct pH or rock fertilizers to correct deficiencies as you dig your garden. In any case, it’s always wise to incorporate organic matter as you work.

Soil Enrichment

If you’re an experienced gardener with an established garden site, you can take steps to replenish soil nutrients and organic matter as soon as you harvest and clear out your garden in fall. Sow seed of a cover crop in your garden, or cover the soil with a thick layer of organic mulch to protect your soil and replenish organic matter content. See the Cover Crops and Mulch entries for details on using both of these to improve your soil. In spring, you’ll be ready to push back or incorporate the mulch or green manure and start planting.

If you don’t plant a cover crop, spread compost over your garden in spring and work it into the soil. The best time to do this is a few weeks before planting, if your soil is dry enough to be worked. Be conservative when you work the soil. While some cultivation is necessary to prepare seedbeds and to open up the soil for root growth, excess cultivation is harmful. It introduces large amounts of oxygen into the soil, which can speed the breakdown of soil organic matter. Never cultivate extremely wet soil, because that will compact it instead of aerating it.

Other opportunities for improving your soil will crop up at planting time, when you add compost or other growth boosters in planting rows or holes, and during the growing season, as you mulch your developing plants.

Planting

Spring can be the busiest time of year for the vegetable gardener. Some careful planning is in order. To help you remember what you have planted and how well cultivars perform in your garden, keep written records. Fill in planting dates on your garden map as the season progresses. Later, make notes of harvest dates. If you would like to keep more detailed records, try keeping a garden journal, or set up a vegetable garden data file on index cards or your computer. With good records, you can discover many details about the unique climate in your garden, such as when soil warms up in spring, when problem insects emerge, and when space becomes available for replanting.

Getting Set to Plant

Once the soil is prepared, lay out your garden paths. Then rake loose soil from the pathways into the raised rows or beds. As soon as possible, mulch the pathways with leaves, straw, or another biodegradable mulch. Lay mulch thickly to keep down weeds. If you live in a region that has frequent heavy rain, place boards down the pathways so you’ll have a dry place to walk.

You can prepare planting beds and rows as much as several weeks before planting. However, if you plan to leave more than 3 weeks between preparation and planting, mulch the soil so it won’t crust over or compact.

Plant arrangement: There are practically no limits to the ways you can arrange plants in a vegetable garden. In a traditional row garden, you’ll probably plant your crops in single rows of single species. If you have raised rows or raised beds, you can interplant—mix different types of crops in one area—and use a variety of spacing patterns to maximize the number of plants in a given area.

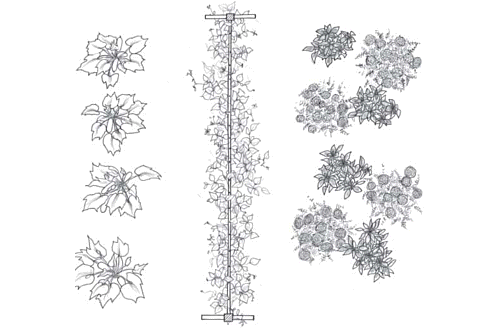

Single rows are good for upright, bushy plants and those that need good air circulation such as tomatoes and summer squash. Use double rows for trellised crops such as cucumbers and for compact bushes such as snap beans and potatoes. Matrix planting is good for interplanting slow-and fast-growing crops. Plant slow growers such as Brussels sprouts, leeks, peppers, or tomatoes, then fill in between them with fast-growing crops like leaf lettuce, radishes, or bush beans. The fast growers will be ready to harvest by the time the slower-growing plants need the space. See the illustration below for ideas on planning the layout of your garden crops.

Planting combinations: Succession cropping is growing two vegetable crops in the same space in the same growing season. You’ll plant one early crop, harvest it, and then plant a warm-or hot-season crop afterward. To avoid depleting the soil, make sure one crop is a nitrogen-fixing legume, and the other a lighter feeder, or add plenty of compost to the soil after harvesting the first crop. All vegetables used for succession cropping should mature quickly. For example, in a cool climate, plant garden peas in spring, and follow them with cucumber or summer squash. Or after harvesting your early crop of spinach, plant bush beans. In warm climates, try lettuce followed by field peas, or plant pole beans and then a late crop of turnips after the bean harvest. In Southern zones where the season is long and summers are sweltering, consider growing a spring to early summer garden, then let the garden lie dormant during the hottest summer weather. Then replant the garden in late summer or early fall for a harvest that lasts through early winter.

Spacing and interplanting. Use single rows for bushy crops like zucchini, and double rows with a trellis down the middle for beans and other vining crops. With slow growers like peppers, try filling spaces between with low-growing annual flowers that attract beneficial insects.

Planting for extended harvest: If you’d like to expand your vegetable gardening horizons, one of the most exciting challenges is extending the harvest into fall and winter. It takes some advance planning to accomplish this, especially if you have cold, snowy winters, but some gardeners find the rewards well worth the effort. To learn more about this, see the Season Extension entry.

Seeds and Transplants

Some vegetable crops grow best when seeded directly in place. Other crops will benefit from being coddled indoors during the seedling stage, and will grow robustly after transplanting. See the Seed Starting and Seed Saving entry for complete information on starting vegetables from seed.

Direct seeding: You can plant many kinds of vegetable seeds directly into prepared soil. However, even when you follow seed-spacing directions given on the seed packet, direct-seeded crops often germinate too well or not well enough. When germination is excellent, thin plants ruthlessly, because crowded vegetable plants will not mature properly. When direct-seeding any vegetable, set some seeds aside so you can go back in 2 weeks and replant vacant spaces in the row or bed.

Soil temperature and moisture play important roles in the germination of vegetable seeds. Very few vegetable seeds will sprout in cold soil. High soil temperatures also inhibit germination. Also, be sure to plant seeds at the recommended planting depth, and firm the soil with your fingers or a hand tool after planting to ensure good contact of seed and soil.

Starting seeds indoors: Starting seeds indoors offers several advantages: You can get a head start on the growing season, keep on planting when outdoor conditions are too hot and dry for good seed germination, and try rare and unusual cultivars. Tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, onions, and celery are almost always started from seed indoors, and cold-climate gardeners might add lettuce and members of the squash family to this list.

Keep in mind that most vegetable seedlings need strong light to grow well. A sunny windowsill is adequate for vegetable seedlings, but natural sun and supplemental artificial light is best. Also remember that vegetables started indoors are protected from stress factors such as wind, fluctuating temperatures, and intense sunlight. One week before you plan to transplant, begin hardening off vegetable plants by exposing them to these natural elements. Move them to a protected place outdoors, or put them in a cold frame.

If temperatures are erratic and windy weather is expected, use cloches to protect tender seedlings from injury for 2 to 3 weeks after transplanting. Remove cloches when the plants begin to grow vigorously—a sign that soil temperature has reached a favorable range and roots have become established. See the Transplanting and Season Extension entries for more details.

In late summer, sun and heat can sap moisture from the new transplants of your fall crops faster than the roots can replenish it. Protect seedlings and transplants with shade covers instead of cloches. You can cover plants with cardboard boxes (prop them up to let air circulate under them) or bushel baskets on sunny days for one week after transplanting, or you can cover them with a tent made of muslin or some other light-colored cloth.

Care During the Season

After the rush of planting, there’s a lull while most of your crops are growing, flowering, and setting fruit. But regular plant care is important if you want to reap a good harvest later in the season. Get in the habit of taking regular garden walks to thin crops, pull weeds, and check for signs of insect and disease problems.

Weeding

Start weed control early and keep at it throughout the season. Remove all weeds within 1 foot of your plants, or they will compete with the vegetables for water and nutrients. If you use a hoe or hand cultivator, be careful not to injure crop roots.

Some vegetables benefit from extra soil hilled up around the base of the plant. When hoeing around young corn, potatoes, tomatoes, and squash, scatter loose soil from between rows over the root zones of the plants. Once the garden soil has warmed (in late spring or early summer), mulch around your plants to suppress weeds and cut down on moisture loss. If you have areas where weeds have been a problem in the past, use a double mulch of newspapers covered with organic material such as leaves, straw, grass clippings, or shredded bark.

Another solution to weed problems is to cover beds with a sheet of black plastic. The plastic can help warm up cold soil, and it is a very effective barrier to weeds. See the Mulch entry for more information about using black plastic.

Watering

Almost all vegetable gardens need occasional watering, especially from midsummer to early fall. Most vegetables need ½ to 1 inch of water each week, and nature rarely provides water in such regular amounts. Dry weather can strengthen some vegetable plants by forcing them to develop deep roots that can seek out moisture. However, the quality of other crops suffers when plants get too little water. Tomatoes and melons need plenty of water early in the season when they’re initiating foliage and fruit. However, as the fruit ripens, its quality often improves if dry conditions prevail. The opposite is true of lettuce, cabbage, and other leafy greens, which need more water as they approach maturity.

When to water: How can you tell when your crops really need supplemental water? Leaves that droop at midday are a warning sign. If leaves wilt in midday and still look wilted the following morning, the plants are suffering. Provide water before soil becomes this dry.

Weed Control: Long-Term Strategies

Over a period of years, you can reduce the number of weed seeds present in your vegetable garden. Here’s how:

- Mulch heavily and continuously to deprive weed seeds of sunlight.

- Remove all weeds before they produce seeds.

- Plant windbreaks along any side of the garden that borders on woods or wild meadows. Shrubs and trees can help filter out weed seeds carried by the wind.

- Grow rye as a winter cover crop. Rye residue suppresses weed germination and growth.

- Solarize soil to kill weed seeds in the top 3 inches of prepared beds.

If you don’t water in time and the soil dries out completely, replenish soil moisture gradually, over a period of 3 days. If you soak dry soil quickly, your drought-stressed crops will suddenly take up large amounts of water. The abrupt change may cause tomatoes, melons, carrots, cabbage, and other vegetables to literally split their sides, ruining your crop.

Watering methods: Watering by hand using a spray nozzle on the end of a hose is practical in a small garden but can be too time-consuming in a large one. Sprinklers are easier to use but aren’t water efficient because some of the water falls on areas that don’t need watering. And on a sunny day, some water evaporates and never reaches your plants’ roots. Using sprinklers can saturate foliage, leading to conditions that favor some diseases, especially in humid climates. The one situation in which watering with a sprinkler may be the best option is when you have newly seeded beds, which need to be kept moist gently and evenly. See the Watering entry for efficient hand-watering strategies.

In terms of both water usage and economy of labor, the best way to water a vegetable garden is to use a drip irrigation system. See the Drip Irrigation entry for more information.

Irrigation pipes do not take the place of a handy garden hose—you need both. Buy a two-headed splitter at the hardware store, and screw it onto the faucet you use for the vegetable garden. Keep the irrigation system connected to one side, leaving the other available for hand watering or other uses.

Staking

Many vegetables need stakes or trellises to keep them off the ground. Without support, the leaves and fruits of garden peas, tomatoes, pole beans, and some cucumbers and peppers easily become diseased. Also, many of these crops are easier to harvest when they’re supported because the fruits are more accessible. You’ll find many handy tips for staking and supporting crops in the individual vegetable entries as well as in the Trellising entry.

Fertilizing

Keeping the soil naturally balanced with organic matter will go a long way toward meeting the nutrient needs of your crops. Crops that mature quickly (in less than 50 days), like lettuce and radishes, seldom need supplemental fertilizer when growing in a healthy soil, especially if they’re mulched. But vegetables that mature slowly (over an extended period), such as tomatoes, often benefit from a booster feeding in midsummer.

Plan to fertilize tomatoes, peppers, and corn just as they reach their reproductive stage of growth. Sprinkle fish meal, alfalfa meal, or a blended organic fertilizer beneath the plants just before a rain. Or rake back the mulch, spread a ½-inch layer of compost or rotted manure over the soil, and then put the mulch back in place. When growing plants in containers, feed them a liquid fertilizer such as fish emulsion or compost tea every 2 to 3 weeks throughout the season. See the Compost entry for instructions for making compost tea.

Foliar fertilizing—spraying liquid fertilizer on plant leaves—is another option for mid-season fertilization. Kelp-based foliar fertilizers contain nutrients, enzymes, and acids that tend to enhance vegetables’ efforts at reproduction. They’re most effective when plants are already getting a good supply of nutrients through their roots. Use foliar fertilizers as a mid-season tonic for tomatoes, pole beans, and other vegetables that produce over a long period.

Pollination

You’ll harvest leafy greens, carrots, and members of the cabbage family long before they flower. But with most other vegetables, the harvest is a fruit—the end result of pollinated blossoms. A spell of unusually hot weather can cause flowers or pollen grains to develop improperly. Conversely, a long, wet, cloudy spell can stop insects from pollinating. Either condition can leave you with few tomatoes, melons, or peppers, or with ears of corn with sparse, widely spaced kernels. The blossom ends of cucumbers and summer squash become wrinkled and misshapen when pollination is inadequate.

To prevent such problems, place like vegetables together so the plants can share the pollen they produce. One exception is super-sweet and regular hybrid corn: Separate these by at least 25 feet to limit the amount of cross-pollination that takes place, or your harvest may not be true to type.

Tomatoes, corn, and beans are pollinated primarily by wind, although honeybees and other insects provide a little help transporting pollen about the plants. The presence of pollinating insects is crucial for squash, cucumbers, and melons. Plant flowers near these crops to lure bees in the right direction. You’ll find more suggestions for helping with pollination in individual vegetable entries.

Coping with Pests

Pests and diseases of vegetable crops include insects, fungi, bacteria, and viruses, as well as larger animals such as raccoons and deer. Fortunately for organic gardeners, there are ever-increasing numbers of varieties that are genetically resistant to insects and diseases. If you know a pest or disease has been a problem in your garden, seek out and plant a resistant cultivar whenever possible.

Prevention can go a long way toward solving insect and disease problems in the vegetable garden. Also, remember that a weed-free or insect-free environment is not a natural one. If your garden is a diverse miniature world, with vigorous plants nourished by a well-balanced soil and an active population of native beneficial insects and microorganisms, you’ll likely experience few serious pest problems.

Sometimes pests do get out of hand. In most cases, once you’ve identified the pest that’s damaging your crop, you’ll be able to control it by implementing one of the following four treatments:

- Hand pick or gather the insects with a net or hand-held vacuum. As you gather them, put the bugs in a container filled with soapy water. Set the container in the sun until the bugs die.

- Use floating row covers as a barrier to problem insects. Row covers are particularly useful in protecting young squash, cucumber, and melon plants from insects. Remember to remove the cover when the plants begin to flower. You can also wrap row covers around the outside of tomato cages to discourage disease-carrying aphids and leafhoppers.

- Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) gives excellent control for leaf-eating caterpillars. It is often indispensable when you’re growing members of the cabbage family, which have many such pests, and when hornworms are numerous enough to seriously damage tomatoes.

- Spraying insecticidal soap is effective against aphids on leafy greens, thrips on tomatoes, and several other small, soft-bodied pests.

There are other types of barriers, traps, and sprays that help keep vegetable pests under control. For more recommendations, see the Pests entry and individual crop entries.

Diseases: Vegetable crop diseases are less threatening in home gardens than they are in farm fields, where crops are grown in monoculture. When many different plants are present, diseases that require specific host plants have a hard time gaining a firm foothold. Plus, a healthy, naturally balanced soil contains many beneficial microorganisms capable of controlling those that are likely to cause trouble.

If you have a large garden, you can help avoid some disease problems by planting crops in different places in the garden from one year to the next. See the Crop Rotation entry for more information.

Where diseases, weeds, soil-dwelling insects, or root knot nematodes seriously interfere with plant health, you can often get good control by subjecting the soil to extreme temperatures. Leave the soil openly exposed for a few weeks in the middle of winter. In the hottest part of summer, a procedure known as solarization can kill most weed seeds, insects, and disease organisms present in the top 4 inches of soil. See the Plant Diseases and Disorders entry for instructions for solarizing soil.

Animal pests: Rabbits, woodchucks, deer, and other animals can wreak havoc in a vegetable garden. A sturdy fence is often the best solution. For tips on controlling animal pests, see the Animal Pests and Fencing entries.

Harvesting and Storage

As a general rule, harvest your vegetables early and often. Many common vegetables, such as broccoli, garden peas, lettuce, and corn, are harvested when they are at a specific and short-lived state of immaturity. Also be prompt when harvesting crops that mature fully on the plant, as do tomatoes, peppers, melons, and shell beans. Vegetable plants tend to decline after they have produced viable seeds. Prompt harvesting prolongs the productive lifespan of many vegetables. See individual vegetable entries for tips on when to harvest specific crops.

Use “Days to Maturity” listed on seed packets as a general guide to estimate when vegetables will be ready to pick. Bear in mind that climatic factors such as temperature and day length can radically alter how long it takes for vegetables to mature. Vegetables planted in spring, when days are becoming progressively longer and warmer, may mature faster than expected. Those grown in the waning days of autumn may mature 2 to 3 weeks behind schedule.

In summer, harvest vegetables in midmorning, after the dew has dried but before the heat of midday. Wait for a mild, cloudy day to dig potatoes, carrots, and other root crops so they won’t be exposed to the sun. To make sure your homegrown greens are as nutritious as they can be, harvest and eat them on the same day whenever possible.

Refrigerate vegetables that have a high water content as soon as you pick them. These include leafy greens, all members of the cabbage family, cucumbers, celery, beets, carrots, snap beans, and corn. An exception is tomatoes—they ripen best at room temperature.

Some vegetables, notably potatoes, bulb onions, winter squash, peanuts, and sweet potatoes, require a curing period to enhance their keeping qualities. See individual entries on these vegetable for information on the best curing and storage conditions.

Bumper crops of all vegetables may be canned, dried, or frozen for future use. Use only your best vegetables for long-term storage, and choose a storage method appropriate for your climate. For example, you can pull cherry tomato plants and hang them upside down until the fruits dry in arid climates, but not in humid climates. In cold climates, you can mulch carrots heavily to prevent them from freezing and dig them during winter. In warm climates, carrots left in the ground will be subject to prolonged insect damage.

Crops That Wait for You

Few things are more frustrating than planting a beautiful garden and then not being able to keep up with the harvest. Leave your sugar snap peas on the vine for a few too many days, and you might just as well till them under as a green manure crop.

Fortunately, there are many forgiving crops that will more or less wait for you. They include onions, leeks, potatoes, garlic, many herbs, kale, beets, popcorn, sunflowers, hot peppers (for drying), horseradish, pumpkins, winter squash, and carrots. You can measure the harvest period for these crops in weeks or even in months.

To keep your harvest from hitting all at once, stagger plantings. Make a new sowing every 10 days to 2 weeks. Mix early, mid-season, and late cultivars. Bok choy and other Asian greens can be harvested through Thanksgiving.

Never have time to pick all of your fresh snap or shell beans at their prime? Relax. Plant cultivars meant for drying, and enjoy hearty, homegrown bean dishes throughout winter.

You can pick leeks young and small or wait the full 90 to 120 days until they mature. Leeks have excellent freeze tolerance. When protected by mulch, they can be harvested well into winter. In mild winter areas where hard freezes are few, winter is the best time to grow collards, spinach, turnips, carrots, and onions.

In all climates, be prepared to protect overwintering vegetables from cosmetic damage by covering them with an old blanket during periods of harsh weather. Or you can try growing cold-hardy vegetables such as spinach and kale under plastic tunnels during winter months.

Off-Season Maintenance

After you harvest a crop in your vegetable garden, either turn under or pull up the remaining plant debris. Many garden pests overwinter in the skeletons of vegetable plants. If you suspect that plant remains harbor insect pests or disease organisms, put them in sealed containers for disposal with your trash, or compost them in a hot (at least 160°F) compost pile.

As garden space becomes vacant in late summer and fall, cultivate empty spaces and allow birds to gather grubs and other larvae hidden in the soil. If several weeks will pass before the first hard freeze is expected, consider planting a green manure crop such as crimson clover, rye, or annual ryegrass. See the Cover Crops entry for instructions on seeding these crops.

Another rite of fall is collecting leaves, which can be used as a winter mulch over garden soil or as the basis for a large winter compost heap. If possible, shred the leaves and wet them thoroughly to promote leaching and rapid decomposition. You can also till shredded leaves directly into your garden soil.

VERBENA

Verbena. Summer-blooming perennial flowers.

Description: Verbenas bear clusters of small, 5petaled flowers on wiry stems. Rose verbena (Verbena canadensis) has trailing stems with flat flower clusters in rose, white, or purple. Plants are 8 to 18 inches tall. Zones 4–10.

Blue vervain (V. hastata) bears branched spikes of blue flowers on 3- to 5-foot plants. Zones 3–8.

Moss verbena (V. tenuisecta) is a trailing plant, 4 to 8 inches tall, with plentiful clusters of pink, lavender, purple, or white flowers. Zones 7–10.

How to grow: Plant verbenas in well-drained sandy or loamy soil. Give them full sun to part shade. Blue vervain also grows in moist to wet soil. Plants are tough and tolerate both heat and drought. Remove flowers as they fade or prune plants back after flowering to keep them blooming. Propagate by stem cuttings or seed.

Landscape uses: Use rose verbena to weave in and around other perennials such as purple coneflowers (Echinacea purpurea) and ornamental grasses. Use blue vervain as a vertical accent in perennial plantings.

VERONICA

Veronica, speedwell. Spring-and summer-blooming perennials.

Description: Speedwells bear small flowers in spikes above lance-shaped leaves. Veronica incana, woolly speedwell, bears pink or blue-violet flowers on 1- to 1½-foot spikes above spreading 6inch gray mats in summer. Zones 3–8. V. longifolia, longleaf speedwell, produces white, pink, blue, or violet spikes on 2- to 4-foot upright plants in summer. Zones 3–8. V. prostrata, harebell speedwell, grows just 3 to 8 inches tall. ‘Aztec Gold’ bears violet-blue flowers above bright yellow foliage. Zones 3–8. V. spicata, spike speedwell, bears spikes of pink, rose, blue, or white flowers on 1- to 3-foot plants in summer. Zones 4–8.

How to grow: Plant or divide in spring or fall in sun or very light shade and average, well-drained soil. Support tall plants with thin stakes. Cut back to encourage continued bloom. Divide every 3 to 4 years.

Landscape uses: Group in borders and cottage gardens. Harebell speedwell makes an attractive groundcover or path edging. Try woolly speedwell in a rock garden. Spike and longleaf speedwells make good cut flowers.

VIBURNUM

Viburnum, arrowwood. Deciduous or ever green spring-blooming shrubs or small trees.

Description: Virburnums are excellent shrubs for the landscape. These are just a few of the dozens of outstanding species and cultivars available.

Viburnum dentatum, arrowwood viburnum, is a native species with an upright habit, arching with age, and growing to a mature height of 6 to 8 feet. Its oval or round, 2- to 3-inch leaves are coarsely toothed and turn red in fall. Flowers appear in spring, borne in flat, creamy white, 3inch clusters followed by berries turning from blue to black. Zones 4–8.

V. plicatum var. tomentosum, doublefile viburnum, is a deciduous, rounded shrub with a horizontally layered habit, growing 8 to 10 feet tall. Dark green, deeply veined, 2- to 4-inch, toothed leaves turn reddish purple in fall. Flowers are borne in spring in flat, 3-inch clusters with larger, sterile flowers ringing a center of smaller, fertile flowers. These white clusters appear in pairs along the horizontal branches, inspiring the common name. Fruit follows bloom on the fertile flowers, changing from red to black as autumn progresses and the foliage turns dull red. Zones 5–7.

V. prunifolium, black haw, is a small (12- to 15-foot) native tree with a single trunk and a round-headed habit. Broadly oval, finely toothed, 2- to 3-inch leaves turn shades of purple and crimson in fall. White flowers are borne in 4-inch clusters in spring, followed by blue-black fruits. Zones 3–8.

How to grow: Site viburnums in partial shade, with good drainage and even moisture. Prune black haw for form. Doublefile viburnum has vertical watersprouts that ruin the graceful lines of this shrub; remove them annually. Prune the other viburnums for vigorous growth, removing some of the oldest branches a few inches above ground level each year after bloom.

Landscape uses: Plant viburnums in woodland gardens, where their berries are great wildlife food. Viburnums also do well as specimens, hedges, and massed plantings.

VINCA

Periwinkle, vinca, myrtle. Evergreen perennial groundcover.

Description: Periwinkles are hardy, trailing vines that root along the stems. While pretty, both of the commonly grown species are very vigorous spreaders that are difficult to eradicate, and they have been declared invasive in many states. Vinca major, big periwinkle, has glossy oval 1- to 3-inch leaves on 2-foot-long stems. Leaves may be dark green or variegated with cream, and plants bear blue or white 1- to 2-inch flowers in late spring. Zones 7–9. V. minor, common periwinkle or creeping myrtle, is similar to big periwinkle, but bears 1½-inch leaves that are more oblong. Plants produce 1-inch-wide blue, blue-purple, red-purple, or white flowers in spring. Zones 4–9.

How to grow: Periwinkles grow in shade or full sun and quickly outcompete nearby perennials that are less vigorous. Keep them away from sites where they can escape the garden. They are especially invasive in woodlands, where they easily smother native wildflowers. Periwinkles don’t spread as quickly on dry sites as they do on ones with rich, moist soil, and they cannot tolerate hot, dry locations.

Landscape uses: While periwinkles are popular groundcovers, it’s usually best to avoid using them because of their invasive characteristics. If you do decide to grow periwinkles, or already have them in your garden, keep them on sites that will naturally contain them, such as in an island bed under a tree surrounded by lawn or in a planting edged with a concrete walkway, for example. In such situations, they’ll stay put and are pretty underplanted with drifts of white or yellow daffodils. Variegated big periwinkle is often planted in window boxes in the South; in the North, it is commonly treated as an annual.

VINES

Vines are versatile plants with long, flexible stems that climb or scramble. They range from tough, woody plants like grapes, to beloved perennial favorites like climbing roses and clematis, to popular annuals like morning glories (Ipomoea spp.) and sweet peas (Lathyrus odoratus). Several popular vegetables are vines as well, including peas and scarlet runner beans (Phaseolus coccineus). Other popular vines include Boston ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata), Virginia creeper (P. quinquefolia), climbing hydrangea (Hydrangea petiolaris), and passionflowers (Passiflora spp.). Beware: Some of the most notorious and problematic invasive plants are vines as well, including English ivy (Hedera helix), oriental bittersweet (Celastris orbiculatus), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), wintercreeper (Euonymus fortunei), and wisterias (Wisteria spp.).

There are vines for almost any kind of site, sun or shade, as well as rich or poor soil that is loamy, sandy, boggy, or dry. You’re better off matching the vine to the situation than trying to alter the environment to suit the plant. In general, most vines are tolerant of a wide range of cultural conditions. It is the exceptions, such as clematis (which requires cool soil around its roots) or roses (most of which require full sun), that have specialized requirements. Be sure to check the specific needs of any plant before adding it to your garden. For basics on planting, propagating, and pest control, see the Planting, Propagation, Pests, and Plant Diseases and Disorders entries.

How Vines Climb

Vines attach themselves to trellises and other supports in several different ways, and it’s important to understand how each species climbs so you can choose an appropriate support. Some vines wrap tendrils around a support—garden peas and sweet peas climb by tendrils, and need strings or poles that are slender enough for the tendrils to wrap around. Clematis also need slender supports because they attach by twining leafstalks. Other vines wrap the entire stem around the support. Annuals like morning glories climb this way. Wisterias also wrap their stems around supports, and as a result can climb heavy trellises, arbors, and even trees. The weight of the woody vines is considerable, and wisterias also can pull gutters off a house and crush smaller trellises. Grapes use two methods to climb: trailing stems aided by woody tendrils.

Boston ivy and Virginia creeper use adhesive discs at the end of tendrils to attach directly to walls or other supports, while English ivy, wintercreeper, and trumpet vine (Campsis radicans) attach themselves with adhesive rootlets. While vines that can attach with discs or rootlets are useful for covering masonry or brick walls, with time the discs or rootlets can work their way into cracks in the mortar and damage it.

Some vines, such as climbing roses, don’t have any way to attach directly to supports. Instead, they weave up through a trellis (or the branches of a shrub) or can be tied to supports.

Landscaping with Vines

There are countless creative ways to use vines. They’re perfect for adding height and color in a small garden, since they essentially grow in two dimensions. Train them up against a wall or trellis to create a tree-size plant without taking up precious horizontal space. Use vines on fences, gates, and other structures to quickly give a new garden an established look. Or use them to soften the hard edge of your house (or another structure) and link it to the garden by covering it with climbing roses, clematis, or other vines. Vines also can be used to scramble over and hide eyesores such as tree stumps or even falling-down sheds or other structures.

While hedges are traditionally used to create garden rooms, vines also can be used to create green walls around an outdoor room, and they will take up less room than hedges, an important consideration where space is limited. Simply give them something to climb and they will happily create green walls around a sitting area. Or use them to cover an arbor that marks the entrance to a garden. Large woody vines are useful for providing shade when trained over a pergola.

Use vines that attach with discs or rootlets to screen unsightly walls or affix wires to an otherwise flat wall so tendril climbers can scale them. A planting of Boston ivy or climbing hydrangea will transform an ugly concrete wall into a feature and add seasonal interest. Plus, if they are planted on the south-or west-facing wall, vines help cool the house or the space behind the wall.

Use vines to transform an unattractive chain-link fence and create a soft, hedgelike barrier instead. For example, cover the fence with trumpet vine, which will produce showers of brilliant red-orange blooms in midsummer that attract hummingbirds. Also use vines like roses, clematis, or scarlet runner beans to decorate lampposts or pillars, and train vines such as morning glories up into shrubs to add a spot of unexpected color to your garden. Clematis vines can be trained up into shrubs like roses as well, to create a two-season flower display.

Vines also are effective when used to cover deck railings or when they’re grown up and along windows and door frames. They quickly transform a small garden or terrace into a magical hideaway. Annual vines can be grown in window boxes and are useful on terraces. Morning glories, ornamental sweet potato vines, and black-eyed Susan vines (Thunbergia alata) are good window-box choices. And don’t forget attractive vines with edible parts such as scarlet runner beans, cucumbers, pole beans, and peas.

Pruning and Training Vines

While annual vines don’t require much pruning, they do need gentle training to grow up and onto supports. If you’re starting your own vines from seeds, be sure to provide each seedling with a small stake to climb soon after it germinates. Otherwise, the seedlings will quickly tangle together, making them difficult to separate and transplant or train. In the garden, use small stakes or pieces of twiggy brush to give vines the support they need to grow up onto a larger trellis. After they’ve begun to twine around a trellis or other support, check them every few days and redirect stems to keep them climbing in the right direction.

Woody vines do need regular pruning to train and control them. Before cutting anything, though, look hard at the plant to determine what growth isn’t healthy, and what needs to be removed to increase flowering, direct growth, or keep the vine in bounds. The first step in any pruning operation is removal of dead, damaged, and diseased wood. Whether you’re pruning dead or live wood, always use a sharp tool—a hand pruner, lopper, or saw—and make cuts just above a live bud or nearly flush with the stem.

Remove dead, damaged, or diseased wood any time, but only prune live wood after the vine has finished blooming for the season. This means you’ll prune spring bloomers in early summer, summer bloomers in early fall, and fall bloomers in winter or early spring. Pruning depends on the growth habit of the plant. Clinging vines like Boston ivy and Virginia creeper merely need trimming to keep them in bounds. Other vines like wisteria, clematis, and grapes need annual pruning to maximize flowering or fruiting. For more on pruning techniques, see the Pruning and Training and Grapes entries.

VIOLA

Pansy, violet. Mostly spring-and fall-blooming biennials and perennials.

Description: Cheerful biennial Viola × wittrockiana, pansy, bears long-stemmed, five-petalled 1½- to 3-inch-wide, flat blooms in a range of solid colors and combinations, many marked with a dark central “face” or blotch. They begin to bloom in early spring on tight clumps of spatula-like leaves; most types reach less than 1 foot tall. If plants bear numerous small flowers, they are usually sold as violas; these come in the same color range as the larger-flowered pansies. Zones 5–9.

Perennial V. cornuta, horned violet, produces smaller flowers to 1½ inch with a little curved spur (the “horn”) at the back of the flower. Blooms come in many colors, including blue, white, yellow, orange, and purple, often marked with a black or yellow blotch in the center. ‘Rebecca’ is fragrant, with white and yellow petals and purple picotee edges. Spreading evergreen plants grow 6 inches to 1 foot tall. Zones 6–9.

How to grow: For pansies, buy plants or sow seeds indoors (in late winter in the North for spring planting, or in midsummer to fall in the South for late-fall planting). Plant in full sun to light shade (plants fare better in light shade in the South). Give them average, moist but well-drained soil loosened with organic matter. Plant no more than 6 inches apart for a good show. Deadhead regularly and water if dry. Older types die out when hot weather approaches, but many newer cultivars will live on to bloom again in fall.

Plant horned violets in spring or fall; divide every 3 to 4 years. They like the same conditions as pansies but tolerate heat better. They bloom for several weeks each spring, and usually bloom again when cool weather returns.

Landscape uses: Grow pansies in beds, borders, and containers for a splash of early color. They combine well with other early-spring flowers, like forget-me-nots and primroses. Use horned violets in the same way or as a colorful ground- cover for smaller areas. These late-blooming flowers also add color to rock gardens.