9

Getting Back in Shape

Most of us are familiar with muscle atrophy. When you don’t exercise for a few weeks, muscle tone and mass decline. According to Dylan Holly in an article at the Huffines Institute for Sports Medicine and Human Performance website, part of the reason for muscle atrophy is that muscle tissue is itself “energetically costly.”1 What he means is that it takes a lot of energy for your body to just maintain muscle tissue, and so when you don’t use it, your body doesn’t leverage other energy resources to maintain it. Instead, your body simply gets rid of the costly muscle tissue.

For those with eyes to see and ears to hear, you’re probably tracking the analogy. Maintaining your Hebrew is “energetically costly.” Holly gives three passing scenarios that cause atrophy: bed rest, immobilization, or microgravity (outer space). Is your Hebrew on bed rest? How long has your Hebrew been immobilized? Ten days? Ten years? Has your Hebrew perhaps been jettisoned to outer space? Maybe you feel like Ezekiel, looking out over a valley of dry bones. “Can this Hebrew live?” Within the analogy, Hebrew is akin to biological muscle tissue—if we don’t use it, we lose it.

Let me encourage you from my decade of teaching experience. I assure you that there is more Hebrew in the deep recesses of your brain than you realize. You can get it back. When our physical muscles atrophy, we still have the building blocks of muscle tissue in our bodies. We have the amino acids and protein enzymes necessary to produce more muscle tissue. Similarly, the building blocks of your Hebrew are still there. You may have to dig them out of the far corners of your cerebral cortex, but the information is there. You might be shocked at how quickly you can get it back. Not only can you get it back, but you can progress in the language and become a skilled reader and exegete of the Hebrew Bible.

In this chapter, we provide you with both guidelines and inspiration for getting back your Hebrew. You will find a few more testimonials in this chapter than in previous chapters. Why? Because former students like you are both comforted and motivated to hear stories of “Hebrew loss” followed by “Hebrew recovery.” Your story of recovery can soon be added to the testimonials in this chapter.

Rediscover Your Why

Have you ever been part of a church or organization where a leader clearly and repeatedly articulated a vision of where the group was headed and why? When that sort of vision casting is done well, you don’t even notice it. Going in any other direction doesn’t seem reasonable.

To regain your Hebrew, you need to reignite your vision for why the language is worth it. What value have you placed on a deep knowledge of God’s word, and what value do you want to put on a deep knowledge of God’s word? If your actions don’t reflect your desire, then you have a resource of potential energy (stored energy) that can become kinetic energy (energy in action). You have a goal and desire; all you need is to jump-start your action to match that desire. Maybe you’ll go back and read (or reread) chapter 1, in which we articulate the reasons that Hebrew study is worth the struggle. Skim through this book and read the many quotes and devotional asides. Be infected with a burning passion to be as close as possible to the Spirit-inspired words of the prophets. Don’t be content to minister as a “second-hander,” sharing others’ insights from Scripture. Who wants to kiss “through the veil” (of translation) when “kissing on the lips” (Hebrew, Greek) is so much better?

Shame and regret do not provide lasting motivation, so take those emotions to the Lord in prayer. Be assured that the Lord has taken away your shame. Spend time in God’s presence, basking in his full acceptance of you in Christ. Ask for empowerment to regain your Hebrew skills and employ the language for the edification of the church and the glory of God. “Commit to the LORD whatever you do, and he will establish your plans” (Prov. 16:3 NIV).

Be Honest about the Facts

Alongside regaining vision, it’s important to face the dual realities of your Hebrew skills and your schedule. Can you still read Hebrew words? Or do you need to relearn the alphabet and how to pronounce Hebrew? Have you forgotten all your verb and noun morphology or just the rarer forms? Before you start to exercise these muscles again, take some time to evaluate your current ability honestly. Don’t let this initial inventory destroy your motivation. Being honest now will save potential frustration down the road.

Also, honestly evaluate your time. Where are you really spending your time? Realistically, where will you be able to insert Hebrew into an already busy schedule? Chapter 2 of this book contains much information on time management, especially with regard to taming the distractions of technology.

Actively Leverage Your Time

After you assess where your time is going, you’re ready to make changes. Just one or two strategic changes in the way you spend your time will give you the minutes you need to regain Hebrew. A few possible ideas are listed below:

- Set specific limits for TV and movies—only on weekends, for example.

- Install a Hebrew flashcard app on your phone (e.g., Bible Vocab, Quizlet). Or, better, find a set of hard-copy vocab cards like the ones associated with Pratico–Van Pelt. Keep a Hebrew grammar in your car. When you are waiting to pick up your kids from school or for your spouse to come out of a store, seize those five minutes to study Hebrew. Let Hebrew be your default activity when waiting in the car. This may not end up being your lifelong method to pick up your Hebrew pieces off the floor, but while you’re getting jump-started again, it will be helpful to have as many outlets to engage with Hebrew as possible.

- On the flip side of installing a flashcard app, remove time-wasting apps from your phone (e.g., Facebook or Instagram). Looking back on your life, do you really want to say, “You know what characterized my life on a daily basis—a constant willingness to look at the latest distraction, shiny thing, or viral video that entered my field of vision.” I (Rob) once heard someone say, “If I printed out all the stuff I read on the internet and bound it together as a book, I would never buy that book. It would be a terrible book. Why, then, do I waste my time looking at that stuff?”

- Plan a “phone fast” one day per week. It sounds radical, but you can experience what life was like for most Americans before 1997. Although a phone fast may not be a spiritual discipline, I like the analogy of a fast, because usually the hunger pangs during a food fast remind you to seek the Lord in prayer. When the “phone pangs” come, go to your Hebrew Bible. Use the extra time you find to reconnect with Hebrew—and to connect with the local community you have set up, with whom you enjoy this language journey.

- Hang up a laminated list of Hebrew paradigms and vocabulary words in your shower or next to the bathroom mirror. Make a habit of reviewing Hebrew while showering, shaving, or brushing your teeth. I reproduce for my classes a page of review paradigms that are affectionately known as “Shower Sheets” for this very purpose.

No matter your schedule, there is time in your day that can be redeemed for Hebrew. Find those few moments and start to form the habit of using them well. Remember that consistency will bring a far greater return than intensity. Ten minutes every day will pay off more than four hours once a week.

Be Inspired by Others

When I was a teaching assistant while earning my MDiv, my professor taught me a helpful learning strategy for students who were doing Hebrew drills in class. The students would partner up and work drills on the board together. When my professor had me organize the pairs, he would ask me to intentionally pair a stronger student with a weaker student. This naturally helped both partners. The stronger student was able to “teach” the weaker student, thus solidifying the material in his or her mind. Additionally, the weaker student was able to see someone who understood the material in action and could seek to emulate that person. Organizing the pairs like this gave the weaker students someone to look up to.

However, this structure could potentially lead to discouragement for the weaker student. If you feel like a “weaker student,” you can combat the discouragement by recognizing that everyone could use some help. Your Hebrew studies will benefit when you surrender your pride and look to others for help. Most of the time, they will inspire you to press on.

Here are some suggestions for how to be the best “weak” student you possibly can be:

- Acknowledge your struggles with the language unashamedly.

- Rejoice in the gifts and abilities God has given to others to learn Hebrew and be encouraged by their progress rather than being jealous of it.

- Be humble enough to accept help from others.

- Develop a work ethic that will push you to learn even if you don’t feel hardwired to learn languages.

Perhaps for some of you, the challenge is not admitting that your language abilities are weak but admitting that you’ve let your knowledge of Hebrew wane. You need examples of others who have fought to get it back. Nancy Ruth is one of those examples. Nancy studied Hebrew and Greek in college and seminary, but life and ministry crowded out her upkeep of the languages. See her testimony below.

Nancy’s story is not overly complicated. She had the desire and motivation to rekindle her language skills, she developed a plan, and then she executed that plan. As I hope you’ve gathered so far in this book, you can resurrect your Hebrew skills. Some of you just need the motivation of having seen others do it to know it’s possible.

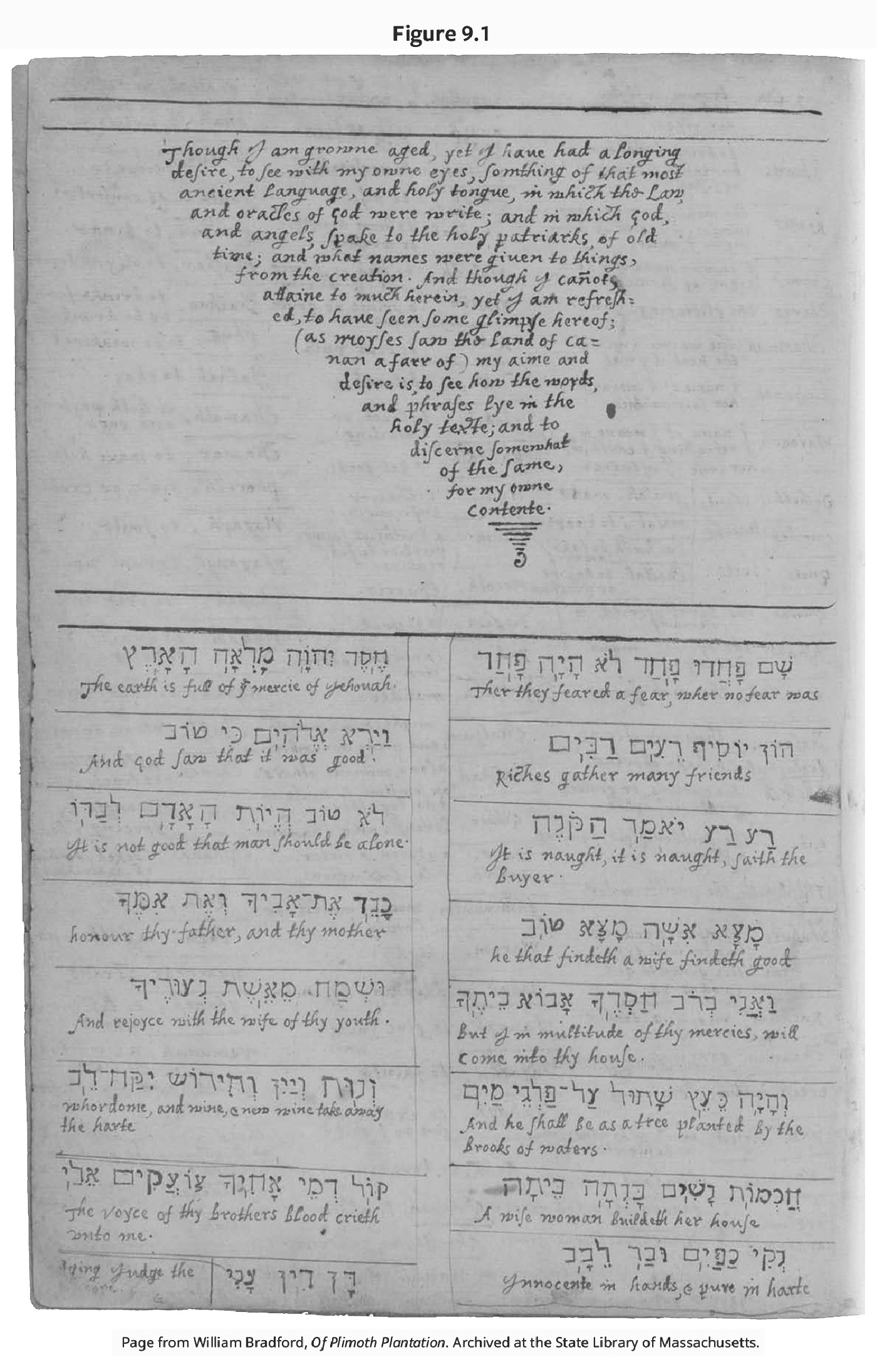

We can also be inspired by historical figures as we find their stories of learning Hebrew. William Bradford was born in March 1590 in Austerfield, Yorkshire, England, and became the governor of Plymouth Colony for thirty years. Bradford recorded the difficulties of the sea voyage on the Mayflower in addition to details of life in Plymouth in his work A History of Plimoth Plantation, 1620–47. In the beginning pages of this work, Bradford wrote a brief description of his desire to learn Hebrew, which he began in his old age (see fig. 9.1). Here are Bradford’s words (with original spelling and formatting):

Though I am growne aged, yet I have had a longing

desire, to see with my owne eyes, something of that most

ancient language, and holy tongue, in which the Law,

and oracles of God were write; and in which God,

and angels spake to the holy patriarks, of old

time; and what names were given to things,

from the creation. And though I cañot

attaine to much herein, yet I am refresh-

ed, to have seen some glimpse hereof;

(as Moses saw the Land of ca-

nan afarr of) my aime and

desire is, to see how the words,

and phrases lye in the

holy texte; and to

dicerne somewhat

of the same,

for my owne

contente.2

In addition to Bradford’s spoken desire to learn Hebrew late in life, he also documented some of his study exercises. These included some short sentences that he would translate, as well as lists of vocabulary words in his own handwriting (of course). Bradford also has a couple pages of Hebrew vocabulary transliterated into English, suggesting that he relied on pronunciation to learn his vocabulary. One of the joys of finding manuscripts like this is that we see a busy man later in his life desiring to learn Hebrew. No matter your age, you can look to William Bradford for motivation to pick up Hebrew and enjoy God’s revelation of himself in the Old Testament.

When my wife and I adopted our son from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we were encouraged by so many others around us who had adopted or who were in the process. We looked to their examples for guidance and motivation. Some people talk about the “adoption bug,” or the notion that once a family adopts, they can’t help but adopt again. I would argue there isn’t a bug per se, but people who have adopted tend to do it again because they learn it is doable. Something that may seem so monumental—raising funds, mountains of paperwork, international details—turns out to be doable. People who have adopted don’t get a bug for the process; they get a bug for the outcome of adoption. Similarly, regaining your Hebrew competence is doable. You won’t catch a bug for the difficult process to get it back, but you may catch the bug for the outcome of knowing God through the Hebrew of the Old Testament. Like my family, you may just need some encouragement from others who have gone before you and have come out on the other side with a deep joy in the Hebrew Bible.

Aim Low

The value of a practice is not found in our ability to do it perfectly. I don’t often—who am I kidding, I never—recommend Urban Dictionary. However, in preparing this section I learned a new word: flawsome. Urban Dictionary defines this word as “something that is totally awesome, but not without its flaws.”3 It seems that the most common use of this word is in relation to an experience, which doesn’t actually fit our context here. Also, I don’t want to imply that “flawsome” communicates something about the value of Hebrew—“Hebrew is great and all, but I’d call it flawsome”—implying that the study of Hebrew has its flaws. Rather, I would argue that we are “not without flaws” in our pursuit of learning and retaining Hebrew. And that’s OK.

In an MIT article by Winslow Burleson and Rosalind Picard, the authors investigate the cognitive “affects” of those who learn through failure.4 One of the detriments to our learning is our inability to properly deal with the negative affections of failure. In the article, Burleson and Picard define a state of “Stuck” in which there is a sense of being out of control, lack of concentration, mental fatigue, the feeling that this task will take forever, and a perceived mismatch between the challenge and one’s skill. If we are honest, many of us live in this state of “Stuck” regarding our Hebrew study, and it cripples us rather than motivates us.

The reality is that we learn more through failure and our inabilities than we do through our perceived perfection. We need to learn to embrace our cognitive weaknesses and continue the valuable pursuit of learning Hebrew. The perfect can be the enemy of the good. If the activity we are doing is worthwhile, we should not be paralyzed by our inability to do it perfectly. We should strive to do our work as well as we can with our imperfect abilities and limited time. If we end up doing it minimally, it was still worth doing.

As you come back to Hebrew, it’s OK to read it poorly. It’s OK to take two years to relearn what you learned in one semester initially. It’s OK to use an interlinear. It’s OK to have forgotten morphological patterns. It’s OK to not even remember what a root is!

One way to embrace our inabilities and continue learning is by setting attainable goals. By doing so, you are positively reinforcing the experience of successfully learning Hebrew. Shoot for reading one verse per day. After you’ve done that for a while, you can gradually increase your commitment.

Maybe your attainable goal is to start with a book intended to expose readers more broadly to the Hebrew language (rather than expecting readers to master paradigms and vocabulary). One book for this is Lee M. Fields, Hebrew for the Rest of Us: Using Hebrew Tools without Mastering Biblical Hebrew (Zondervan, 2008). If you struggled with English grammatical concepts in the past, you might consider starting with the slim paperback by Miles Van Pelt, English Grammar to Ace Biblical Hebrew (Zondervan, 2010). What if you committed to read one of these texts for just five minutes per day? Over the course of the year, you would spend more than thirty hours relearning Hebrew. You don’t have to do everything. Just choose one small and achievable goal within your limitations. Write it down. Commit to it. Share that commitment with someone who will keep you accountable. Now, in the midst of all your flaws, do it.

Harness the Power of Ritual

Most of us naturally fall into various routines or rituals. We sit in the same place at church or in classrooms, we park in the same parking spaces at work, or we begin our days with coffee or tea. Humans are really good at developing habits or rituals and often do so without knowing it. If we can put a little thought and effort into our ability to develop habits, we can leverage those automated behaviors for learning Hebrew. By consciously embracing nonsacred rituals, we attach the totality of ourselves to a habit, directing our lives toward things we choose to value.

In a blog post titled “How to Turn an Ordinary Routine into a Spirit-Renewing Ritual,” Brett and Kate McKay list the essential elements of a ritual as (1) location and atmosphere, (2) objects, (3) timing, and (4) mindset.5 A ritual is a habit performed in self-reflection and style—a method of consciously imprinting a behavior onto all of one’s senses and thus making the habit stick more easily while increasing one’s joy in practicing it.

What would it look like for you to turn your reading of the Hebrew Bible into a ritual? It might mean you buy that expensive calf-leather Hebrew Bible that feels so supple and smells like a new belt. And you might read it in the same favorite place every day. Maybe you read by a fire to remind you of Mount Sinai burning as God revealed the law to Moses. You might enjoy a cup of coffee as part of this daily ritual. The feel of leather. The smell of coffee. A familiar seat. The crackle of a nearby fire. A warm and familiar mug in your hand. A consciousness of being part of the body of Christ to whom this inspired text was written long ago. An expectation of hearing the Spirit speak through the word. By involving your various senses, you create an expectancy in your total person for this daily ritual.

Recruit a Team

I (Rob) recently appeared on a panel that was being asked questions by young men entering the ministry. One questioner asked, “If you could go back twenty years and tell yourself one thing, what would you say?”

“Buy Apple stock,” I answered.

“And,” I added more seriously, “I would tell myself to be sure to have faithful Christian brothers to walk side by side with me in my life and ministry—men to whom I could confess my sin and who would pray for me and hold me accountable” (James 5:16).

God created us to live in community. How foolish we are to attempt life or ministry alone—or to think we can persevere in a biblical language by ourselves. As you reboot your Hebrew, prayerfully seek other Christians who can join you in that commitment. Better yet, find someone who is faithful in reading the Hebrew Bible and ask that person to pull you along. With social media, it should be easy to reconnect with an old friend from college or seminary. If there is someone in your city with whom you can read the Hebrew Bible (another pastor, perhaps), how wonderful to enjoy face-to-face fellowship over the word of God!

Become a Hebrew Scribe

At this point in the book, you have no shortage of time-management and study methods from which to choose. So, what’s one more? Maybe you need one final audible or trick play in order to gain an advantage over the Hebrew defenses. Here’s my suggestion: write down at least one Hebrew verse in longhand every day, saying it aloud, reading it, and writing it. If you want to make writing Hebrew more of a ritual (see above), perhaps use a leather journal and fountain pen and write by candlelight.

My wife does this in English with a resource called Journibles.6 These are premade books that have blank lines for you to write the verses and jot down some thoughts from the passage. Perhaps you purchase one of these but write the text in Hebrew. Recent studies show that information that is written by hand is retained better than typed information or information that one simply reads or hears. Researchers do not fully understand why, but various studies reach the same undeniable conclusion—handwriting one’s notes results in better learning.7

Seek Professional Intervention

Another desperation call from the line of scrimmage: seek the help of a professional. We all seek professional intervention at times. When your health fails, you go to a doctor. When your car breaks, you go to the mechanic. When your marriage is struggling, you go to a counselor.

If you have employed tactics mentioned above and you are still struggling, why not seek out professional help to resurrect your Hebrew? Be willing to spend a little money for the professional help too. I’ve found that people take more seriously the things that they are actually paying for—note, for example, the amazingly high attrition rates of students in free online courses.8

What would seeking professional help look like? Here are some possible avenues:

- Take an online or on-campus Hebrew course at a college or seminary.

- Contact a Hebrew professor and ask for recommendations in hiring a graduate student to tutor you. Skype or Google Hangouts makes remote tutoring available in almost any location.

- Do you have a vacation home in Hawaii? Contact a Hebrew professor (e.g., the one helping with this textbook) and trade a few days of full-fledged Hebrew intervention for a week’s use of your vacation home. ☺

Spare the Next Generation

In Deuteronomy 6:6–7, Moses encourages Israel to diligently teach (שׁנן) “these words” (הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלֶּה) to their children. Deuteronomy 6 continues by saying that these words will be integral to Israel’s existence as a people and that they will be a teaching tool when future generations ask about the Lord’s mighty acts. I’ll grant you that the illustration breaks down. If we pass on to our children the original biblical languages, there is something fundamentally different from that than passing on to them the mighty acts of God in their heart language. Even so, think of the joy it could bring to pass on those mighty acts of God in the original languages.

It is pretty well established that children learn new languages faster than adults. How we all wish we could go back and study Hebrew and Greek in our childhood! We cannot. But we can give the next generation what we failed to receive. You can teach Hebrew to children in your home, in a local Christian middle school, or in a homeschooling cooperative. And if you do this, you will experience a wonderful truth: there’s nothing like teaching something to really make you learn it—or relearn it. In addition to teaching them the original biblical languages, you will also help establish in your children or students skills and accountability so they don’t share your story of regret (assuming you have spent time wandering from the Hebrew fold).

I realize how radical this suggestion sounds. Some of you may be just trying to learn basic vocabulary again, yet I’m suggesting that you teach Hebrew to the next generation! But what if this vision of seeing others delight in Hebrew to the same degree you will is what motivates you to jump in with both feet? What if the drive to teach others the original language of the Old Testament motivates you not only to learn a few additional vocabulary words but also to develop your own memory devices for the qal paradigm?

When I was in high school, I spent three years studying Spanish. I never really felt like I knew Spanish super well while studying it, but to this day I can remember more than I thought I learned at the time. While working at the gym during seminary, I learned to interact with the Spanish-speaking community in our town (at least insofar as I could make sure they understood the terms of the gym contract). It was so rewarding to be using information I learned years ago, information I honestly didn’t know I had retained. In my current position, I practice speaking Hebrew with a colleague, and he is the director of the Hispanic programs at our institution. I sometimes find myself speaking to him in Hebrew and then randomly throwing in a Spanish word. I’m not consciously thinking to switch to Spanish. But when my brain switches out of English, I’m not yet good enough at modern, spoken Hebrew to keep out the Spanish influences. The point is that I learned far more Spanish as a youngster than I thought.

There’s something about the young human brain that absorbs knowledge like a sponge. The church father Irenaeus (ca. 130–202), reflecting on the strength of his childhood recollections of Polycarp, poignantly captures this reality:

I remember the events of those times [my childhood] much better than those of more recent occurrence. As the studies of our youth growing with our minds, unite with it so firmly that I can tell also the very place where the blessed Polycarp was accustomed to sit and discourse; and also his entrances, his walks, the complexion of his life and the form of his body, and his conversations with the people, and his familiar [discussions] with John, as he was accustomed to tell, as also his familiarity with those who had seen the Lord.9

Let us labor to imprint the words of Scripture on the next generation’s minds—even the Hebrew words of the inspired authors. What a joyful and momentous task! If we teach others (or even if we teach ourselves), let us whisper under our breaths this prayer/poem of the Greek grammarian James Hope Moulton:

At the Classroom Door

Lord, at Thy word opens yon door, inviting

Teacher and taught to feast this hour with Thee;

Opens a Book where God in human writing

Thinks His deep thoughts, and dead tongues live for me.

Too dread the task, too great the duty calling,

Too heavy far the weight is laid on me!

O if mine own thought should on Thy words falling

Mar the great message, and men hear not Thee!

Give me Thy voice to speak, Thine ear to listen,

Give me Thy mind to grasp Thy mystery;

So shall my heart throb, and my glad eyes glisten,

Rapt with the wonders Thou dost show to me.10

- Name one adjustment in your daily schedule that would allow for five minutes of Hebrew study or reading of the Hebrew Bible. Can you make that adjustment right now?

- List elements of a morning or evening ritual that you can combine with the study of Hebrew or the reading of the Hebrew Bible. Try rebooting a Hebrew habit through your new ritual.

- Do you need professional intervention? Contact a local Bible college or seminary about an on-campus or online class. Or look into hiring a skilled graduate student to tutor you.

- Who could walk together with you as you reconnect with Hebrew? If you can’t think of someone, prayerfully ask the Lord to direct your path to a Hebrew co-laborer.

- Is there someone to whom you can teach Hebrew? Your children? Perhaps you can teach at a local Christian school or homeschool co-op? Start your own YouTube channel? There’s nothing like teaching Hebrew to really learn it!

After you finish reading this book, consider signing the pledge below. Make a copy of your signed pledge and display it somewhere to remind you of your commitment.

The Exegetical Value of the Masoretic Accents in 1 Kings 18:29

“And it came about at the passing of the midday, that they prophesied intensely until the offering of the oblation; but there was no voice, and there was no answer, and there was no attentiveness.”

וַֽיְהִי֙ כַּעֲבֹ֣ר הַֽצָּהֳרַ֔יִם וַיִּֽתְנַבְּא֔וּ עַ֖ד לַעֲל֣וֹת הַמִּנְחָ֑ה וְאֵֽין־ק֥וֹל וְאֵין־עֹנֶ֖ה וְאֵ֥ין קָֽשֶׁב׃

—1 Kings 18:29

The interpretive benefit of the Masoretic accents is a debatable topic.11 However, since these were originally cantillation marks (for singing and memorization), they at least play a minimal role in where the emphasis of the verse may lie. The accents do not always point to an important interpretive key to a verse, but they can provide insight into an interpretation or nuance of the text that may not be apparent in an English translation.

In 1 Kings 18:29, the Masoretic accents provide direction on where to break the translation in order to emphasize that no one heard the prophets of Baal crying out. The ESV translates 1 Kings 18:29 as, “And as midday passed, they raved on until the time of the offering of the oblation, but there was no voice. No one answered; no one paid attention.” This translation captures the general idea of the verse and can be trusted. However, notice the difference between my translation above and the English translation represented here. The ESV puts a period after “voice,” suggesting that there is a major thought break in the sentence. In this sense, the main point is “there was no voice,” and “no one answered; no one paid attention” is a further clarification of “there was no voice.” The Hebrew, however, places all the negative particles together and by repetition emphasizes the idea that no deity in the entire cosmos heard the outcry of Baal’s prophets.

The athnaḥ is the key accent in 1 Kings 18:29. In the translation above, the athnaḥ would be represented by the semicolon after “oblation.” It represents a minor but significant pause in the verse. Following the athnaḥ, the Hebrew Bible gives a threefold negation, all with the negative particle אֵין: “There was no voice, there was no answer, and there was no attentiveness.” This threefold negation provides an emphasis similar to the “holy, holy, holy” of Isaiah 6, and the athnaḥ sets these phrases off grammatically. This minor change in the punctuation of 1 Kings 18:29 emphasizes the lack of response from anyone in the cosmos. Absolutely no one, neither in the created world nor in the spiritual world, heard the cry of the prophets of Baal.

The deafness of false deities reminds us of the folly of turning to anything or anyone besides the Lord God. The Lord God has provided every good and perfect gift to his people in Christ. As Peter says in John 6:68, “To whom would we go?” The deafness of false deities helps us realize how ridiculous we are to call on any “god” besides the Lord (cf. Isa. 44:9–20). There will be no voice; there will be no answer; there will be no attentiveness. The Lord God is the only God (2 Kings 19:19; Ps. 86:10; Isa. 37:16; John 1:18; 1 Tim. 1:17; Jude 25).

1. Dylan Holly, “Muscle Atrophy Cures Found at the Supermarket,” Huffines Institute, May 28, 2018, https://www.huffinesinstitute.org/Resources/Articles/ArticleID/1696/Muscle-Atrophy-Cures-Found-At-The-Supermarket.

2. William Bradford, A History of Plimoth Plantation. We discovered this text in a blog post by Phillip Marshall at Houston Baptist University (HBU), “It’s Never Too Late to Learn Hebrew . . . ,” Biblical Languages (blog), October 25, 2018, https://biblicallanguages.net/2018/10/25/its-never-too-late-to-learn-hebrew/. Marshall comments that Diana Severance, the director of HBU’s Dunham Bible Museum, sent him this text with the image of the page in Bradford’s manuscript. The digital manuscripts of Bradford’s work can be found on the website of the State Library of Massachusetts, https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/208249. A special thanks to Diana Severance for her help in locating these resources and to Phillip Marshall for drawing our attention to them.

3. https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Flawsome. This is not to be confused with “flawesome,” which Urban Dictionary defines as an under-the-breath, sarcastic way of making someone think you actually said “awesome.”

4. Winslow Burleson and Rosalind Picard, “Affective Agents: Sustaining Motivation to Learn through Failure and a State of ‘Stuck,’” (paper, MIT Media Lab, Cambridge, MA), https://affect.media.mit.edu/pdfs/04.burleson-picard.pdf.

5. Brett McKay and Kate McKay, “How to Turn an Ordinary Routine into a Spirit-Renewing Ritual,” The Art of Manliness, December 7, 2015, http://www.artofmanliness.com/2015/12/07/how-to-turn-an-ordinary-routine-into-a-spirit-renewing-ritual/.

6. Reformation Heritage Books currently has Old Testament volumes for Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Deuteronomy, Proverbs, and Psalms; see https://www.heritagebooks.org/categories/Journibles/.

7. See the various studies summarized in Robert Lee Hotz, “The Power of Handwriting,” Wall Street Journal, Tuesday, April 5, 2016, D1–D2.

8. Jonathan Haber, “MOOC Attrition Rates—Running the Numbers,” HuffPost, November 25, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jonathan-haber/mooc-attrition-rates-runn_b_4325299.html.

9. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 5.20.5–6, trans. C. F. Cruse (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998), 178.

10. Poem printed on unnumbered front page of the first separately published fascicle of James Hope Moulton, A Grammar of New Testament Greek: Accidence and Word-Formation, vol. 2, part 1, General Introduction: Sounds and Writing, ed. Wilbert Francis Howard (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1919). The poem, written in Bangalore, India (where Moulton was serving as a missionary), is dated February 21, 1917.

11. This devotional originally appeared at https://adamjhowell.wordpress.com on October 29, 2016.