Bedfordshire

FATHER OF ENGLISH CLOCK-MAKING

∗ FIRST ENGLISH BEST-SELLER ∗ MAYPOLE DANCING

∗ MORRIS DANCING

Houghton House – John Bunyan’s ‘House Beautiful’.

BEDFORDSHIRE FOLK

Admiral Byng ∗ Samuel Whitbread ∗ John Howard ∗ Harold Abrahams ∗ John Le Mesurier ∗ Ronnie Barker ∗ Arthur Hailey ∗ Paul Young

∗ Monty Panesar

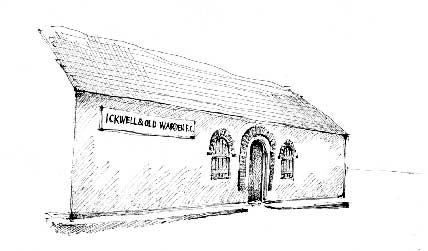

Thomas Tompion

1639–1713

England’s Father Time, THOMAS TOMPION, was born in a small thatched cottage beside the huge green at ICKWELL GREEN, near Biggleswade. He was the son of the village blacksmith and worked in his father’s smithy until he was 25. In the 17th century, blacksmiths were the most proficient engineers of their day, and it was in the smithy that Tompion learned the precision skills he was later to put to good use as a clockmaker’s apprentice in London.

In 1671 Tompion joined the recently formed Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, and was later elected Master. In 1676 Charles II commissioned him to make two clocks for the new Royal Observatory, demanding that they should be accurate enough for astronomers to make calculations by them, and that they should only need to be wound once a year. These helped the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, to prove that the earth spins on its axis at a uniform rate.

Tompion was the first watchmaker to join the Royal Society, and created the first English watches with balance springs, which were much more accurate than earlier watches. He also designed and improved on various types of escapements, or devices to control the rotational movement of wheels, inventing a cylinder escapement that allowed the first flat watches to be made. He was THE FIRST MANUFACTURER KNOWN TO PUT SERIAL NUMBERS ON HIS PRODUCTS.

Tompion was a prolific and innovative watchmaker, producing not just watches but the finest mantel and grandfather clocks in the world. Modern clocks and watches owe much of their design to the techniques he perfected. Known as the Father of English Clockmaking, he is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Close to Tompion’s cottage, with an upturned horseshoe picked out in brick above the door, is his father’s old smithy, now restored and used as a changing room by the local football club.

Tompion’s Clocks

Tompion’s timepieces were so well built that many examples survive and are still working, over 300 years after they were made.

The British Museum has a number of his creations, including his greatest masterpiece, the ‘MOSTYN’, a year clock made for William and Mary and possibly ‘the most valuable clock in the world’.

The Pump Room in Bath boasts one of Tompion’s finest clocks, donated to the city by Tompion himself in 1709 and in full working order. It still only needs winding once a month.

St Mary’s Church at Northill, where Tompion was christened, has a famous one-handed clock made by Tompion on the church tower.

John Bunyan

1628–88

John Bunyan’s THE PILGRIM’S PROGRESS, published in 1678, tells of the adventures of a young man called Christian, burdened down with sins, who must flee the worldly City of Destruction and journey through a land of dangers and temptations towards the heavenly Celestial City. Bunyan uses simple language, colourful characters and vivid visual imagery to make his story widely accessible, and The Pilgrim’s Progress was carried all over the world by English missionaries and explorers, making Bunyan THE FIRST BEST-SELLING NOVELIST IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE. It has been translated into over 200 languages, more than any other book apart from the Bible, and is probably the most widely read religious novel ever written.

Bunyan was born, the son of a tinker, in a small cottage outside Elstow, an attractive village on the outskirts of Bedford. He was a boisterous, energetic boy who enjoyed playing tipcat, a form of rounders, on the village green and had a reputation for being disobedient and rebellious.

In 1644, during the Civil War, he joined the Parliamentary army dreaming of excitement, and his dream came alarmingly true when a soldier who had just replaced him at the siege of Leicester was shot dead. Bunyan began to think that maybe God was keeping him for some deeper purpose.

He returned home to Elstow and reluctantly settled down to be a tinker like his father. The family was poor and Bunyan found village life frustrating, but marriage to a local girl, Mary, mellowed him somewhat. When their daughter was born blind, Bunyan was convinced this was the result of his former life, and he decided to turn from his wicked ways and embrace the Christianity of Cromwell’s Puritan England.

At the Restoration, Charles II attempted to suppress the Puritans, and Bunyan was flung into Bedford gaol for preaching without a licence. Refusing to compromise, he spent the next 12 years in and out of gaol. While inside he made shoelaces for his blind daughter to sell at the gaol gate, so that his wife and four children could buy food, and fashioned himself a flute out of the leg of his prison stool, with which he could entertain his fellow inmates. It was during his third period of imprisonment in 1672 that he began writing the great Christian epic that would make him famous.

Elstow Abbey Church, where John Bunyan rang the church bells

After his release from gaol Bunyan became a Congregational pastor in Bedford and continued to publish books and travel around the countryside preaching. He died of a cold in London in 1688 and is buried in Bunhill Fields.

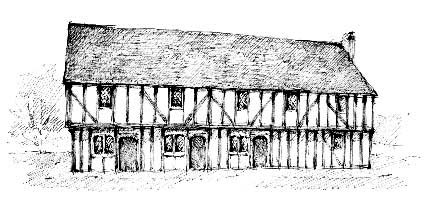

The village green at Elstow where Bunyan used to play tipcat and where the annual Elstow Fair was held remains largely unchanged. At one end of the green is the lovely timber-framed Moot Hall, built in the 15th century by the nuns of Elstow Abbey as a market stall for the fair, and for use as a courthouse and schoolroom. It is now a museum in his memory.

Elstow Abbey was founded in the 11th century by Judith, niece of William the Conqueror, and became the third largest in England. All that is left is the magnificent church with its detached bell tower where, as a young man, Bunyan would ring the bells, all the while gazing upwards nervously in case they fell down on his head as a punishment from God.

Inside the main body of the church are the Norman font where Bunyan was baptised and where he later brought his blind daughter Mary to be christened, the balustrade where he would kneel for Communion, and the seat he used when attending services.

In the floor of the north aisle of the church is one of only two brasses in all England to portray an abbess.

Maypole Dancing

Ickwell Green is famous for its Mayday celebrations, which have been held on the green for over 400 years, and is one of the only villages in England to have a permanent maypole.

Maypole dancing takes place on village greens all over England on May Day, and is a celebration of fertility, new life and the start of the growing season. In the 16th century the young people of the village would go out and gather up garlands of spring flowers and hawthorn branches, as referred to in the rhyme ‘Here we go gathering nuts (or knots) in May’. The hawthorn, which blossoms in May, is also known as the May Tree and is symbolic of fertility.

In earlier, pagan days a hawthorn branch was stuck in the ground, and the young people would attach a strip of their clothing to it as an offering to the country spirits for an abundant harvest of both crops and children. Then they would dance around it in celebration, weaving intricate patterns with the ribbons and pay court to Flora, the goddess of flowers, as represented by the May Queen, the ‘fairest maid’ in the village, who would be seated on a throne wearing a crown of flowers.

The hawthorn was eventually replaced by the maypole and strips of clothing by brightly coloured ribbons. The custom of having children dance around the maypole was introduced by John Ruskin in 1881.

The tallest maypole ever known stood outside St Mary-le-Strand in London and was 143 ft (44 m) tall.

Morris Dancing

Morris dancing is also associated with May Day, although it is performed at other times of year as well, and is traditionally danced by the men of the village. Based on a pagan ritual, the actual Morris dance is derived from a style of ‘Moorish’ dancing introduced into Europe by the Moors in the 15th century, and taken up enthusiastically by the Tudor court in England.

The dancers wear jingles attached to their legs and dress in white, with differently coloured belts and jackets depending which part of the country they are in. Six or eight dancers wielding sticks line up facing each other and go through a variety of dances to the accompaniment of, in earlier times, a pipe and tabor, in more modern times a violin or accordion.

By the end of the 19th century Morris dancing had virtually died out. In 1899 the musician and teacher Cecil Sharp happened to witness a special performance in Oxford, which inspired him to tour the country researching the various forms of Morris dancing that survived. In 1911 he founded the English Folk Dance Society, and this led a revival in the popularity of Morris dancing and the folk music that accompanies it.

Well, I never  knew this

knew this

about

BEDFORDSHIRE FOLK

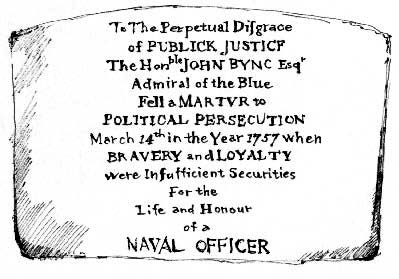

Admiral Byng

1704–57

JOHN BYNG was born at SOUTHILL PARK, fourth son of a distinguished admiral, the 1st Viscount Torrington.

He enlisted in the Navy at 14, and thanks in part to his illustrious father’s influence, rose quickly through the ranks. In 1756, by now an admiral, Byng was sent by a dithering government to reinforce the British garrison on the island of Minorca against the French.

Byng’s squadron was small and ill-equipped, and before he could land the relief force, a French fleet appeared. There followed an inconclusive sea-fight, during which the French were repulsed, but a number of the English ships were damaged. Byng judged that his scant relief force was insufficient to repel a French attack on the fort, and rather than abandon them on the island to suffer inevitable rout and capture, he sailed back to Gibraltar for repairs and to treat the wounded, leaving Minorca to fall to the French.

The English government, appalled by what they saw as an embarrassing defeat, summoned Admiral Byng back to England for court martial. They refused to accept that their own indecision and lack of preparation were partly to blame and tried to whip up resentment against Byng, leaking stories that he was a coward and a liar.

Byng was cleared of cowardice, but found guilty of not having ‘done his utmost against the enemy, either in battle or pursuit’. This carried the death penalty, and on 14 March 1757 he was shot on the quarterdeck of the HMS Monarch, in Portsmouth Harbour. The brutality of the execution shocked the public. The French author Voltaire, arriving in Portsmouth on the very day of the killing, was so disgusted by the whole episode, which had been closely followed throughout Europe, that he was moved to write in his novel Candide: ‘In this country they see fit to shoot an admiral from time to time to encourage the others’ – ‘pour encourager les autres’.

Admiral John Byng was carried home to Southill, where he was laid to rest beside his father in the Torrington vaults in All Saints Church.

Samuel Whitbread

1720–96

SAMUEL WHITBREAD was born in the village of CARDINGTON, the son of a Bedfordshire farmer. At the age of 16 he was apprenticed to a London brewer by his widowed mother, and at 22 he laid the foundations of his industrial empire when he used his inheritance to invest in a small brewery. At this time ale was being promoted as a healthy alternative to the demon gin, and the business flourished. In 1750 Whitbread built his own brewery in London’s Chiswell Street, the first purpose-built, large-scale brewery in the country, which soon grew into THE BIGGEST BREWERY IN BRITAIN.

Whitbread was one of the first people to make a fortune through ‘trade’, which was much looked down upon by 18th-century society, but he was also one of the first great philanthropists, who believed in using the fruits of his success for the benefit of all. Whitbread ran his business with a concern for the welfare of his workforce, and his greatest contribution to the industrial society of which he was a pioneer was the template he created for honest business practice and good relations between management and workers.

In 1768 Whitbread was elected MP for Bedford, a post he held for over 20 years, and he was THE FIRST MAN TO SPEAK OUT IN PARLIAMENT AGAINST SLAVERY. In 1795 he bought nearby Southill Park from the Byng family, and his descendants still live there today.

Samuel Whitbread is buried in St Mary’s Church in Cardington.

John Howard

1726–90

JOHN HOWARD was born in London but would often visit Cardington, where his grandmother had a farm, and became firm friends with Samuel Whitbread. In 1756 he came to live in Cardington and his fine house still stands close to the church. Independently rich, Howard travelled far and wide and was once imprisoned by a French privateer and forced to endure appalling conditions, an incident which sparked his interest in the plight of those in prison.

In 1773 he became High Sheriff of Bedfordshire and set off on a tour of the county’s gaols. He was horrified by what he found. They were filthy, overcrowded and diseased. Men and women were herded together like cattle. The innocent had to pay their gaoler for their release, which they usually were unable to do, and so were kept unjustly confined. Howard raised all these issues in Parliament and sponsored several bills for reform. He carried on his crusade all over Britain and then on the Continent. In 1790, having prophetically left his affairs in order, he travelled to Russia to visit military hospitals, contracted typhus there, and died. He is buried in Russia beneath a simple tombstone which reads, ‘Whosoever thou art, thou standest at the grave of thy friend’.

John Howard’s statue in Bedford

John Howard of Cardington was held in such esteem that a statue of him was placed in St Paul’s Cathedral – the first time a commoner had ever received such an honour. THE HOWARD LEAGUE FOR PENAL REFORM is named in his honour.

Born in Bedford

HAROLD ABRAHAMS (1899–1978), winner of the gold medal for the 100 metres at the 1924 Olympics in Paris, a feat immortalised in the 1981 Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire.

JOHN LE MESURIER (1912–83), actor, best remembered for his role as Sergeant Wilson in the BBC sitcom Dad’s Army.

RONNIE BARKER (1929–2005), comic actor, known for his starring roles in The Two Ronnies, Porridge and Open All Hours for the BBC. He was also a prolific writer who sent in material under the fictitious name Gerald Wiley, so that it would be ‘judged on merit’.

Born in Luton

ARTHUR HAILEY (1920–2004), best-selling author of novels such as Hotel and Airport.

PAUL YOUNG, pop singer and the first voice heard on the 1984 Band Aid single ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’, born 1956.

MONTY PANESAR, cricketer and the first Sikh to represent England, or any nation other than India, at Test cricket, born 1982.

knew this

knew this