Buckinghamshire

CHILTERN HUNDREDS ∗ AN ENGLISH INVENTION

∗ FREEDOM OF CONSCIENCE ∗ GREATEST ENGLISH POEM ∗ HELLFIRE ∗ ENGLISH HYMNAL ∗ PANCAKE RACE

Jordans Quaker Meeting House, built in 1688. Burial place of William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania.

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE FOLK

John Hampden ∗ George and William Grenville ∗ Benjamin Disraeli

∗ Sir George Gilbert Scott ∗ Major George Howson

∗ Herbert Austin ∗ Roald Dahl

Chiltern Hundreds

Buckinghamshire has always been at the forefront of British politics, particularly the Chilterns, which have even lent their name to a political procedure. To resign as a Member of Parliament is forbidden, but an MP who wishes to step down between elections may apply for the ‘STEWARDSHIP OF THE CHILTERN HUNDREDS’. The Chilterns were once plagued by ruffians and highwaymen, and so a Steward was appointed by the Crown to impose law and order. Anyone who held an office paid for by the Crown was prohibited from sitting as an MP, and thus, by applying for the post, an MP would effectively disqualify himself from sitting in the House.

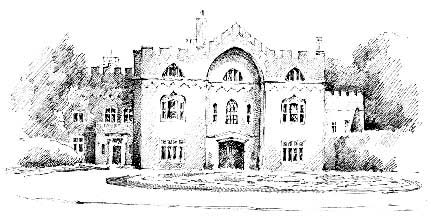

Bletchley Park

During the Second World War, BLETCHLEY PARK, a Victorian mansion now on the edge of Milton Keynes, was very much in the front line. In 1939 a small group of mathematicians and crossword puzzle enthusiasts were assembled here, in total secrecy, with orders to crack Germany’s Enigma code. To begin with, using knowledge smuggled in by the Poles of how the Enigma worked, mathematician ALAN TURING, regarded as the founder of modern computer science, developed an apparatus that could decipher a large number of Enigma machines at one time, and this proved key in helping the team to unravel the code. This feat allowed England to monitor German plans for bombing raids and U-boat attacks, and shortened the war by two years, according to Winston Churchill.

In order to process messages even faster, Alan Turing’s lecturer from Cambridge, PROFESSOR MAX NEWMAN, and engineer TOMMY FLOWERS, using Turing’s theories on computation as a basis, designed and built ‘COLOSSUS’, the world’s first programmable electronic computer. It is to them that we owe the computers that run the world today, and yet for a long time the invention of the computer was credited to the Americans – because Colossus and Bletchley Park remained covered by the 30-year rule of the Official Secrets Act until 1974.

Bletchley Park was ENGLAND’S FIRST GOVERNMENT LISTENING POST, and forerunner of today’s GCHQ at Cheltenham. The mansion itself was saved from demolition and is now run as a museum, complete with a working model of Colossus, in memory of the vital work done there and its contribution to winning the Second World War.

Jordans

Tucked away down an undulating country lane near Beaconsfield is JORDANS, a hidden place of supreme importance to English freedoms both at home and overseas.

There is a Tudor farmhouse, a barn made with timbers from the Mayflower, one of the earliest Quaker meeting-houses, and the simple graves of men and women who fought for the freedom of English people to think for themselves.

Amongst those lying here is THOMAS ELLWOOD (1639–1713), a leading Quaker who learnt young what it meant to question authority. On becoming a Quaker, as a young man, he refused to take off his hat at meal times in case that signified a deference to his father which should be shown only to God, whereupon his father confiscated all Thomas’s hats and beat him roundly for such impudence. Ellwood went on to edit the journals of George Fox (1624–91), founder of the Society of Friends, and read for John Milton, who was going blind (see Milton’s Cottage).

Another Quaker buried here is WILLIAM PENN (1644–1718), the son of a famous admiral, and the founder of the State of Pennsylvania.

The Quakers’ belief that every individual has a personal relationship with God and should be free to worship God without the intervention of priests, brought them into conflict with the Church authorities, and many Quakers, including Penn, were persecuted and imprisoned.

In 1670 William Penn’s father died, leaving him a considerable fortune and a debt of £16,000 owed by Charles II. In lieu of the debt Penn was granted land in the American colonies, and he founded Pennsylvania, named in honour of his father, as a place where those fleeing persecution in England could live and worship freely by their own or Quaker principles. He named the principal settlement Philadelphia, which is Greek for ‘brotherly love’. And in the tiny meeting-house at Jordans, in 1701, William Penn wrote his CHARTER OF PRIVILEGES, Pennsylvania’s original constitution. With its emphasis on human rights, religious freedom and the inclusion of ordinary citizens in the law-making process, it was a template for the American Constitution.

By virtue of his friendship with James II, Penn persuaded the King to issue a Declaration of Indulgence, allowing everyone in England to worship God in their own way, and thereafter persecution of all religious sects ceased. Some of the more fundamentalist groups disapproved, suspecting the Catholic King of merely trying to gain freedom for the Roman Catholic religion, which they despised, but William Penn believed in freedom for all, not just his own, and he would not back down. He remains one of the most courageous and influential fighters for freedom of conscience in English history.

In 2005 Jordans Meeting House, built in 1688, suffered a serious fire, but has since been restored as near as possible to its original state.

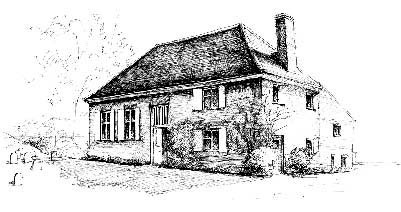

Milton’s Cottage

Not far away from Jordans, in the village of CHALFONT ST GILES, is a pretty timber-framed brick cottage – the last and only remaining home of JOHN MILTON. He rented it from his friend and reader Thomas Ellwood, and came here in 1665 to escape the plague and finish his epic poem PARADISE LOST, about man’s fall from grace. When he showed the poem to Thomas Ellwood, Ellwood replied, ‘Thou hath said much here about Paradise Lost, but what hast thou to say about Paradise Found?’ And so Milton wrote Paradise Regained, about Satan’s unsuccessful temptation of Jesus in the desert.

It is largely for these two works that Milton is regarded as one of the greatest poets in the English language. Thomas Jefferson conceded that he was greatly influenced by the style and ideas of Milton when he was writing the American Declaration of Independence.

Milton’s Cottage now houses a museum in his memory.

West Wycombe

The picture book village of WEST WYCOMBE, slumbering on the old London to Oxford coach road, is kept safe by the National Trust. It consists of a street lined with timbered houses, a grand Palladian mansion with park and, forming a prominent landmark on top of a steep hill, the distinctive church of St Laurence. Crowning the 14th-century church tower is a golden ball with seating for six where, in the 18th century, SIR FRANCIS DASHWOOD and his friends would meet and play cards, drink and sing ‘jolly songs very unfit for the profane ears of the world below’.

In fact, in the world 300 ft (90 m) directly below, profanity and worse was a regular occurrence, for here, in caves dug out of the chalk, would meet the infamous Hellfire Club. Sir Francis Dashwood, who owned West Wycombe, was a wealthy London merchant with a wide circle of friends centred on Frederick, Prince of Wales, who made up ‘The Knights of St Francis of Wycombe’, or the Hellfire Club. In the 1750s Dashwood had mined the hill below the church for material to make the straight stretch of road into High Wycombe that you can see from the hill. The Hellfire Club, which used to meet in Medmenham Abbey a few miles away, began to gather in the caves, which reached quarter of a mile (0.4 km) into the hillside. The meetings, for which the men were dressed in white flowing robes, were secret, lasted all night and gained a reputation as wild, Bacchanalian orgies – especially as only ladies of ‘a cheerful and lively disposition’ were invited.

In 1763, as so often happens, rough-house led to tears, and the club was disbanded. One night at Medmenham Abbey, Sir Henry Vansittart, Governor of Bengal, brought along as his guest a baboon from India. John Wilkes, the cross-eyed radical, journalist and MP for Aylesbury, thought what fun it would be to dress the animal up as the Devil and conceal it in a box. At just the right moment he let it out and the poor creature sprang from the box on to the back of the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, who cried out in terror, ‘Spare me gracious Devil, thou knowest I was only fooling, I am not half as wicked as I pretended!’ The Earl and the baboon both fled from the chapel. The baboon was never seen again, while the Earl retired into private life to do Good Works. The Hellfire Club limped on as a pale imitation before finally closing in 1774.

The church is often open and it is sometimes possible to climb into the golden ball. There are daily tours into the caves, which can also be hired for dinner parties, wedding receptions or other entertainments.

English Hymnal

The hymn ‘AMAZING GRACE’, which became a No. 1 hit for the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards in 1972, was written in the 1760s by slave-trader turned hymn-writer JOHN NEWTON, while he was a curate in the north Buckinghamshire village of Olney. His great friend, who also lived in Olney, was poet WILLIAM COWPER, whose most famous work was the comic ballad THE DIVERTING HISTORY OF JOHN GILPIN. Together they wrote the Olney Hymns, a collection of nearly 350 hymns, including ‘God Moves in a Mysterious Way’ and ‘How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds’.

Pancake Race

Olney is famous for its annual Shrove Tuesday PANCAKE RACE, dating back to 1445. Apparently it began when a harassed housewife, hearing the church bells, rushed off to church still clutching her frying pan. Those taking part must be women over 18 who have lived in Olney for over three months. They must wear the clothing of a traditional housewife and run 400 yards from the market-place to the church, while tossing pancakes. The winner gets a kiss from a bell ringer and a silver cup.

Well, I never  knew this

knew this

about

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE FOLK

John Hampden

1594–1643

HAMPDEN HOUSE, hidden in the hills near Princes Risborough, was the ancestral home of England’s greatest parliamentarian, JOHN HAMPDEN, a cousin of Oliver Cromwell. In 1637 Hampden refused to pay the King’s Ship Tax, originally levied on ports but extended by the extravagant Charles I to include inland areas as well. Hampden’s defiance of the King on a point of principle – that the King could only raise taxes through Parliament – made him a hero, and he was one of the five MPs the King tried to arrest in Parliament in January 1642. The King took the Speaker’s chair and asked Speaker Lenthall if the men he wanted were there, to which the Speaker answered, ‘May it please your Majesty, I have neither eyes to see, nor tongue to speak in this place, but as the House is pleased to direct me…’ ‘I see my birds have flown,’ replied the King.

This incident lit the fuse of the English Civil War, and resulted in the Monarch being banned from the House of Commons for evermore. It is the origin of the ceremony during the State Opening of Parliament, when Black Rod goes to the Commons, on behalf of the Monarch, to summon MPs for the Queen’s Speech, and has the door slammed in his face in a gesture that symbolises the Commons’ independence.

Hampden was killed at the Battle of Chalgrove Field in 1643 and is buried amongst his ancestors in the lovely old church next to Hampden House. He was the staunchest architect of parliamentary democracy and the greatest defender of its privileges. As one commentator said, ‘Never Kingdom received a greater loss in one subject.’

George and William Grenville

In Wotton Underwood lies the prime minister whose actions sparked the American War of Independence. GEORGE GRENVILLE (1712–70), whose family were once Dukes of Buckingham, introduced the Stamp Act in 1765. This stipulated that the American colonies should bear some of the cost of ‘defending, protecting and securing the British colonies and plantations’. Every document in America was made subject to a stamp duty, in one of the first attempts to impose taxes on goods imported into the colonies. The colonies, who had no voice in the British Parliament, naturally protested, calling for ‘no taxation without representation’. They were ignored, and thus were sown the seeds of rebellion.

In Burnham church, nestling amongst the beech trees, lies George Grenville’s son WILLIAM WYNDHAM GRENVILLE (1759–1834), who also had a profound effect on the United States, for he was the prime minister under whose ‘Ministry of all the Talents’ the Slave Trade was abolished in 1807.

Benjamin Disraeli

1804–78

Queen Victoria’s favourite prime minister, and England’s first and only Jewish-born prime minister, BENJAMIN DISRAELI lived at Hughenden Manor near High Wycombe, and is buried in a vault in the church next door, beneath a memorial erected for him by the Queen herself.

Sir George Gilbert Scott

1811–78

SIR GEORGE GILBERT SCOTT was born in the village of GAWCOTT, just south of Buckingham. He restored over 500 English churches and left us with some fine English icons – the Martyrs’ Memorial in Oxford, the Albert Memorial in London, for which he was knighted by a grateful Queen Victoria, and most spectacular of all, the immense gothic St Pancras Station, now restored as the terminal for the Channel Tunnel railway.

His grandson, SIR GILES GILBERT SCOTT (1880–1960), designed England’s biggest cathedral at Liverpool, Battersea and Bankside power stations – the latter is now the Tate Modern – and the original red telephone box.

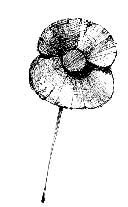

Poppies

Sleeping in the churchyard at HAMBLEDEN is war hero MAJOR GEORGE HOWSON MC, the man who brought us the Remembrance Day poppy. Disabled in the First World War, he founded the Disabled Society specifically to find work for disabled war veterans like himself. In 1921 the British Legion started to sell poppies to help ex-servicemen, and Major Howson designed an artificial poppy that could be made by someone who had lost the use of a hand. He set up a workshop for five disabled veterans off the Old Kent Road, but this quickly outgrew its premises, and in 1922 he founded the Poppy Factory in Richmond, Surrey, which still produces millions of poppies every year.

HERBERT AUSTIN, 1ST Baron Austin (1868–1941), founder of Austin Cars, was born in LITTLE MISSENDEN. In 1906 Austins became the first cars to be manufactured at the Longbridge plant, in Birmingham. In the 1930s Austin was Britain’s biggest car manufacturer, producing the iconic Austin Seven.

ROALD DAHL (1916–90), children’s author, is buried in GREAT MISSENDEN, location of the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre. He is remembered for stories such as Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and The Big Friendly Giant.

knew this

knew this