Middlesex

WORLD’S OLDEST FILM STUDIOS ∗ EALING COMEDIES

∗ THE LONGITUDE PROBLEM ∗ EARLY CARTOONIST

∗ G AND T

Alexandra Palace, the birthplace of BBC television.

MIDDLESEX FOLK

Matthew Arnold ∗ Evelyn Waugh ∗ Sir Alan Ayckbourn ∗ John Constable ∗ Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies ∗ Lord Joseph Lister

∗ Sir Charles Wyndham ∗ Francis James Barraud ∗ Marie Lloyd ∗ Nigel Balchin

Ealing Studios

EALING STUDIOS are THE OLDEST FILM STUDIOS IN THE WORLD. They were established in 1902 by Will Barker, who made silent movies there until, with the introduction of the ‘talkies’ in the 1920s, the studios were taken over by Associated Talking Pictures and rebuilt as the studios there today.

It was after the Second World War, in the late 1940s and early 50s, that Ealing Studios had their heyday, producing the classic ‘EALING COMEDIES’ for which they are famous. Since it was almost impossible to get hold of Hollywood films during the war, Ealing Studios had been forced to develop their own English brand of film-making, and the Ealing comedies built on this heritage, portraying England as a charming, rather quaint place, full of dogged characters battling to keep the country unsullied.

The films are consistently anti-authority and, rather like the novel 1984, which George Orwell was working on at that time, feature the struggles of the little man up against a faceless bureaucracy or corporate bullying. The films are feel-good fantasies that give expression to the ordinary Englishman’s dreams of rebellion, where pluck and ingenuity can win out over tyranny, rather as England herself had won out over the might of Germany.

These characteristics come to the fore in films such as Kind Hearts and Coronets, Passport to Pimlico and The Lavender Hill Mob, all of which were released in 1949 and made stars of actors such as Alec Guinness and Margaret Rutherford.

A coarser but equally funny example of this very English humour surfaced ten years later in the Carry On films, of which 30 were made at various locations between 1958 and 1978.

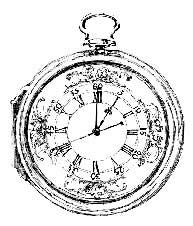

John Harrison

1693–1776

Buried in the churchyard of St John’s Church, HAMPSTEAD, is the horologist JOHN HARRISON, whose marine chronometer solved the ‘longitude problem’ – how to calculate the distance east or west a ship had sailed – which had baffled such luminaries as Galileo, Sir Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley.

Longitude is the angular distance from any meridian (in this case the Prime Meridian at Greenwich), and is vital in calculating a ship’s position at sea. Until Harrison’s clock, sailors had to rely on guesswork, and many had lost their lives as a result of mistaking where they were. Perhaps the most famous example occurred in 1707, when the fleet of Admiral Sir Clowdisley Shovell miscalculated its position and was wrecked off the Scilly Isles, with the loss of over 2,000 lives.

The principle behind the calculation of longitude is simple. For every 15 degrees travelled eastward the local time moves forward by one hour; for every 15 degrees travelled west it goes back by one hour. If you know the local time, and also the time at a fixed point (in this case Greenwich), then you can calculate your longitude. In those days, while it was easy enough to calculate the local time by using the sun and stars, the only way to tell the time at Greenwich was with a clock, and the only clocks that existed then were pendulum clocks, which were rendered useless by the motion of the sea.

In 1714 Parliament set up ENGLAND’S FIRST SCIENCE FUNDING BODY, THE BOARD OF LONGITUDE, which offered a prize of £20,000 to whoever could invent a means of calculating longitude to within 30 miles (48 km), after a voyage of six weeks to the West Indies.

John Harrison, a humble joiner with a passion for making clocks, was determined to win the prize and, at the fourth attempt, he designed a timepiece that looked like a large watch, with a new balance mechanism unaffected by the sea. It lost just five seconds in six weeks at sea and Harrison claimed the prize, but the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, miffed that his own experiments with lunar charts had failed, persuaded the bureaucrats on the Board not to award the money to the upstart Harrison. Harrison spent the rest of his life petitioning Parliament for his money, which he was finally awarded just before he died, on the personal intervention of George III. H4, an exact replica of Harrison’s prize-winning design, was carried by Captain Cook on his two final voyages of discovery. Cook called it ‘our faithful guide through all the vicissitudes of climate’. John Harrison’s ingenuity revolutionised sea travel, and for a while gave the English a huge advantage in the race to explore the globe.

William Hogarth

1697–1764

WILLIAM HOGARTH is the only major English artist to have a roundabout named after him, a dubious honour that would no doubt have tickled him, as one of England’s great satirists. The roundabout, a busy junction on the M4 at Chiswick, lies close to Hogarth’s House, where the artist lived during the summer months for the last 15 years of his life, with his wife Jane, daughter of SIR JAMES THORNHILL, THE FIRST ENGLISH-BORN ARTIST TO RECEIVE A KNIGHTHOOD.

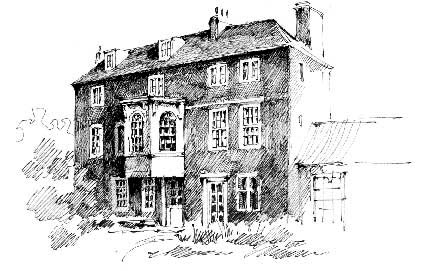

Hogarth’s House

Gin and Tonic

One of Hogarth’s most evocative pictures is Gin Lane, which portrays the debauchery and degradation of a 17th-century London awash with cheap gin.

Gin was invented in Holland in the mid-17th century by Dr Franciscus Sylvius, as a cure for stomach disorders. It is distilled from grain spirits flavoured with juniper oil, and the name comes from ‘genever’, the Old Dutch word for juniper. English soldiers serving in Holland developed a taste for gin, which they called ‘Dutch courage’.

Gin production was then promoted in England by William of Orange, who slapped a tax on French brandy, and since it was already cheap to make, being a by-product of ordinary grain, gin rapidly became the tipple of choice for the poor, leading to the rampant drunkenness and disorder depicted in Hogarth’s picture. The government tried to curb this by bringing in the Gin Act of 1736, which led to rioting in the streets and drove gin distilling underground.

The development of the more refined London Dry Gin in the late 19th century made gin more respectable, and it became an essential ingredient in the newfangled cocktails.

‘Pink Gin’, with angostura bitters, a tonic formulated from herbs in the West Indies, was popular amongst naval officers, while gin and tonic was developed for the British army in India. The quinine in tonic water was believed to help fight off malaria, and the addition of gin made the tonic more palatable.

London Dry Gin is considered best in a gin and tonic, while Plymouth Gin, distilled in Plymouth since 1793, is preferred when making a Dry Martini Cocktail.

William Hogarth started life as a copper engraver, but soon turned to painting as a more lucrative occupation, and became known for his narrative pictures that told moral tales, in an early form of the comic strip. The eight pictures in his celebrated The Rake’s Progress tell of the dissolute life of wealthy Thomas Rakewell, who throws away his inheritance on drinking, whoring and gambling, and ends up in Bedlam, a reflection of the decline Hogarth saw all around him. He loved to poke fun at self-serving politicians and at affectation, and he was especially good at capturing real life, as he had an almost photographic memory and could remember scenes that he could later recreate in the most precise detail. It was this realism, both in the subject and the artwork, that he is remembered for.

Well, I never  knew this

knew this

about

MIDDLESEX FOLK

Born in Middlesex

MATTHEW ARNOLD (1822–88), poet and renowned literary critic, was born in LALEHAM. His father was Thomas Arnold, headmaster of Rugby School, famously portrayed in Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Both father and son are buried in the family plot in the churchyard of All Saints, Laleham.

EVELYN WAUGH (1903–66), novelist (Decline and Fall, A Handful of Dust, Scoop, Brideshead Revisited), was born in FORTUNE GREEN.

SIR ALAN AYCKBOURN, the writer of 71 full-length plays, and the most successful and prolific English playwright since William Shakespeare, was born in HAMPSTEAD in 1939.

Buried in Middlesex

JOHN CONSTABLE (1776–1837), pre-eminent English landscape painter, is buried in the churchyard of St John’s, Hampstead.

ARTHUR AND SYLVIA LLEWELYN DAVIES, parents of the boys who inspired J.M. Barrie’s ‘lost boys’ in Peter Pan, are buried in the churchyard of St John’s, Hampstead. Peter Pan himself, PETER LLEWELYN DAVIES (1897–1960) lies in Hampstead Cemetery in Fortune Green.

Also buried in Hampstead Cemetery are:

LORD JOSEPH LISTER (1827–1912), the pioneer of anti-septic surgery, after whom Listerine is named.

SIR CHARLES WYNDHAM (1837–1919), actor-manager and founder of Wyndham’s theatre. Trained as a doctor, but by inclination an actor, Wyndham travelled to America to find work and served as an army surgeon under Ulysses S. Grant in the American Civil War. In 1863 he managed to obtain employment as an actor at Grover’s Theatre in Washington, where the leading man was John Wilkes Booth, who two years later would murder President Abraham Lincoln. Wyndham later recalled: ‘I saw nothing there that would foreshadow such an act as his except where the subject of politics was introduced. Then, even in those days of heated discussion, his excitement was remarkable, and his friends who wished to be on pleasant terms with him, gradually learned to avoid the discussion of politics.’

FRANCIS JAMES BARRAUD (1856–1924), who painted ‘Nipper’ the dog on the His Master’s Voice record label.

MARIE LLOYD (1870–1922), the ‘Queen of the Music Hall’.

NIGEL BALCHIN (1908–70), who thought up the name for Britain’s bestselling chocolate bar, the Kit Kat, and who also conceived the Aero chocolate bar.

knew this

knew this