Oxfordshire

ENGLAND’S SMALLEST CATHEDRAL ∗ OXFORD CULTURE

∗ OXFORD MARTYRS ∗ AN EARLY ENGLISH CAPITAL

∗ AN EARLY ENGLISH FAMILY

∗ ENGLAND’S OLDEST STATE SCHOOL

∗ PROVISIONS ∗ NATIONAL GALLERY OF WORDS

Home of the Oldest English University

OXFORDSHIRE FOLK

Lady Celia Fiennes ∗ Sir Ranulph Twisleton Wykeham Fiennes ∗ Flora Thompson ∗ Dorothy L. Sayers ∗ P.D. James ∗ Lennox Berkeley

∗ Jacqueline du Pré ∗ Stephen Hawking ∗ Hugh Laurie

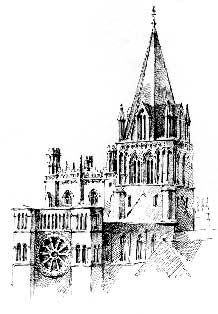

Oxford Cathedral

Built on the site of an 8th-century Saxon church of St Frideswide, the present OXFORD CATHEDRAL, which is 12th-century Norman, is THE SMALLEST OF ALL ENGLISH CATHEDRALS. It is also unique in being THE ONLY CHURCH IN THE WORLD THAT IS BOTH A CATHEDRAL AND A COLLEGE CHAPEL. In 1524, a few years before the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Cardinal Wolsey took over what was then the Priory church of St Frideswide, intending to demolish it and use the land for a new ‘Cardinal’s College’. Fortunately he died before this could happen, and the old church survived as the chapel for the new college. In 1546 Henry VIII gave it to the first Bishop of Oxford as his cathedral, while at the same time it continued to serve as the chapel of the college of Christ Church.

Oxford Culture

Oxford has ENGLAND’S FIRST BOTANICAL GARDENS, which were opened in 1621 – the first in the world were created by the Venetian nobleman Daniele Barbaro, in Padua in Italy in 1545.

Opened in 1683, Oxford’s ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM was THE FIRST OFFICIAL PUBLIC MUSEUM IN THE WORLD – indeed the word ‘museum’ had to be created to describe it. The original contents came from the private collection of plants and curiosities gathered from around the world by the gardening Tradescants, father and son, and stored in their private museum in South Lambeth, the Ark. The collection was willed to the antiquarian Elias Ashmole, who donated it to Oxford, along with his own books and artefacts.

Oxford was also the scene of THE FIRST ENGLISH IQ TEST. It was conducted in 1908 by Sir Cyril Burt, using various groups of schoolchildren, and utilising the scale developed by French psychologist Alfred Binet.

Oxford also gives us the OXFORD BOOK OF ENGLISH VERSE, which first appeared in 1900, edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch, and OXFAM (Oxford Committee for Famine Relief), England’s leading aid agency, founded in 1942 by a group of Oxford people, to send food to German-occupied countries such as Greece, which were suffering from British trade embargoes.

In 1954 Oxford hosted the first successful attempt to run A MILE IN UNDER FOUR MINUTES. The feat, which had been thought impossible, was achieved by 25-year-old ROGER BANNISTER, who covered the mile in 3 minutes 59.4 seconds at Oxford’s Iffley Road sports ground.

Oxford Martyrs

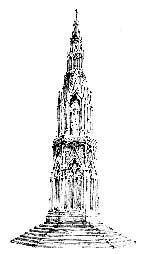

On Broad Street, in the centre of Oxford, stands Sir George Gilbert Scott’s Martyrs’ Memorial, marking the spot where the Oxford martyrs Latimer, Ridley and Cranmer were burnt at the stake during the reign of Bloody Queen Mary. In 1553 Mary began the task of restoring England to the Catholic faith, and to this goal she had nearly 300 Protestant dissenters burnt and executed. Hugh Latimer, Bishop of Worcester, and Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London, refused to recant their Protestant faith and in 1555 were condemned to a fiery death. As the flames took hold Latimer cried out, ‘Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as I trust shall never be put out.’

The following year Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, was burnt at the stake on the same spot, despite recanting at the last minute. When he got to the stake, Cranmer thrust his right hand into the flames first – the hand with which he had signed his recantation. His death, and the manner of it, are said to have advanced the cause of the Reformation more than any other martyrdom.

Dorchester

The beautiful Oxfordshire town of DORCHESTER was once a capital of England, and its unostentatious but ravishing little abbey, once a cathedral. It stands beside the River Thame, near where it meets the River Thames, on the spot where Christianity was confirmed as the principal religion of England. Here, in the 7th century, St Birinius baptised the Saxon King Cynegils of Wessex, in front of King Oswald of Northumbria, uniting them against the last pagan king, Penda of Mercia. Dorchester remained a cathedral until King Alfred transferred part of the see to Winchester in the 9th century. The present abbey church dates from Norman times and possesses a rare Jesse window, with the Tree of Jesse illustrated not only in the stained glass but also on the stone mullions. The Tree burgeons upwards from a reclining Jesse, the delicate boughs exquisitely carved with Biblical figures, mirrored in the window lights and complemented by the faint memory of vivid ancient wall paintings. A glorious composition to find in a lovely, almost forgotten town.

Upriver from Dorchester, the correct name for the Thames is the Isis. However, the river is now only known by this name as it runs through the city of Oxford.

Alice, Duchess of Suffolk

Lost in a fold at the foot of the Chilterns is the pretty, wooded village of EWELME, where a gently flowing brook leads the quiet main street past mellow cottages, water-cress beds, manor house and church.

Lying beneath a sumptuous monument in the church at Ewelme is the last of one of England’s first great families, ALICE CHAUCER, DUCHESS OF SUFFOLK.

Alice was the granddaughter of Geoffrey Chaucer, author of the first great work written in the English language, the Canterbury Tales. Chaucer’s sister-in-law, Katherine Swynford, was mistress and then third wife of the mighty John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, third surviving son of Edward III. Geoffrey’s oldest son, Thomas Chaucer, fought at Agincourt, rose high in the favour of Henry V and married an heiress, Matilda Burghersh, who brought him the manor of Ewelme. Their only child was Alice, married as a child to John Phelip, who was killed at Harfleur, then to the Earl of Salisbury, who died at the siege of Orleans, and finally to William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk.

In 1444 Suffolk was responsible for negotiating the marriage of Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou, and he and Alice travelled to France to bring the new Queen to England, where she stayed as a guest in their palace at Ewelme.

As Lord High Chamberlain and the power behind the throne of the young King Henry, Suffolk was blamed for the loss of English lands in France, notably by his arch-enemy the Duke of York, who wanted to install his own son Edward (later Edward IV) on the throne. At York’s prompting, Suffolk was banished to the Continent, but he never reached his exile. His ship was waylaid off the coast of Kent, probably by agents of York, and Suffolk was hustled into a small boat where he was beheaded with six strokes from a rusty sword, and his body dumped on the beach near Dover.

Alice lived on at Ewelme, where she left a wonderful heritage, a group of medieval buildings without parallel in an English village. They owe their superb state of preservation to the fact that they are built of brick, a new and costly material at that time, and also because Ewelme has been left largely undisturbed over the years, being far from any main roads and well concealed in its own valley.

The schoolhouse, put up by Alice in the 1430s, is still used as a school and is THE OLDEST SCHOOL IN THE STATE SYSTEM STILL HOUSED IN ITS ORIGINAL BUILDING. Most other schools established at that time, notably Eton, founded in 1440 under the Earl of Suffolk’s supervision for Henry VI, became private schools.

Ewelme School

Next door are the superb cloistered almshouses, designed for 13 poor men and fashioned around a square, flower-filled courtyard. They are still run as almshouses by the Ewelme Trust.

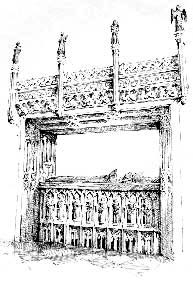

A steep, covered stairway leads to St Mary’s Church, which shows signs of William de la Pole’s Suffolk influence with space, light, a high roof and flint walls. The interior retains its screen and high, pinnacled oak font cover, and is rich with monuments and carving because, according to the villagers, Cromwell’s rampaging soldiers couldn’t find the village. In St John’s Chapel are the simple tombs of Thomas and Mildred Chaucer, their portraits picked out in bronze on top.

But the chief treasure is the dazzling, stone-carved Gothic monument of the last of the Chaucers, Alice, Duchess of Suffolk. On the lid of the tomb, lying beneath a grand stone canopy and watched over by monks and princes, the alabaster figure of Alice rests, her pillow attended by angels. She wears the order of the garter on her arm, one of the few women so honoured, and apparently Queen Victoria came here to learn how the garter should be worn by a lady.

Inside the cabinet is an emaciated figure covered by a shroud, gazing up at an amazing hidden frescoed roof, which can only be seen by lying down on the floor next to the tomb.

Outside in the churchyard a much less ostentatious gravestone marks the burial place of JEROME K. JEROME (1859–1927), author of Three Men in a Boat.

Of Alice’s grand home, where Henry VIII honeymooned with Catherine Howard, and Queen Elizabeth stayed, little remains, just a few bits of wall embedded in the Georgian manor house which stands on the site.

The Provisions of Oxford

OXFORD is a name that has long reverberated through the story of the English, as home to THE FIRST ENGLISH UNIVERSITY. When Henry II discovered in 1167 that his rebellious Archbishop Thomas à Becket had taken refuge in France, he petulantly ordered all the English students who were studying over there to return home. Many came to Oxford, renowned as a place of scholarly debate since the time of Alfred the Great, and set up halls of learning similar to those they had known on the Continent. The first college, University College, was founded by William of Durham, in 1249.

Nine years later, in 1258, Oxford experienced the first stirrings of English democracy when Simon de Montfort and a group of disgruntled nobles, upset by Henry III’s expensive foreign commitments, met in Oxford and drew up THE PROVISIONS OF OXFORD. These reaffirmed and refined the principles of Magna Carta, and formally stripped the King of his absolute power by setting up a number of committees and councils to oversee church matters and taxation. A ‘Council of Fifteen’ was formed which Henry had to consult over the handling of the ‘common business of the realm and of the king’. These bodies would meet several times a year at a Great Council or Parliament.

Henry’s subsequent disregard for the Provisions led to war between the King and the barons, and in 1265 Simon de Montfort looked to widen his support by summoning the barons, the knights of the shires and some burgesses, or ‘commoners’, to meet at Westminster for England’s, and the modern world’s, first truly representative Parliament.

The Provisions of Oxford was THE FIRST DOCUMENT OF ITS KIND TO BE WRITTEN IN ENGLISH AS WELL AS IN FRENCH AND LATIN, so that it could be understood by everyone – which is the aim of another of Oxford’s contributions to English . . .

The Oxford English Dictionary

A‘National Gallery of the race of English words’ is how editor Frederick Furnival described his vision for the OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY in 1861. He reckoned it would take four years to compile – in fact the first edition was not completed until 1928.

The OED is THE LARGEST RECORD OF ENGLISH WORDS, containing over 600,000 words and 2.5 million quotations – William Shakespeare is the most quoted writer, with Hamlet the most quoted of his works, while George Eliot is the most quoted female. The OED is continually being updated, although an obscure book written in 1634 is still the most quoted source of neologisms or new words – physician Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, described as ‘a sort of private diary of the soul’ and full of imaginative vocabulary and imagery.

The most common word in the English language is ‘the’. The most common noun is ‘time’, the most common verb is ‘be’ and the most common adjective is ‘good’.

Because the English language was taken to the New World by the Pilgrim Fathers, and to Africa and the East by the British Empire, it is the most widely spoken second language in the world, and is now the language of the computer age – over 80 per cent of information stored electronically is written in English.

It also helps that English originates from and continues to borrow from so many different sources – mostly Latin, Saxon, Viking, French – and does not have too many fixed rules, making it the richest and most adaptable resource for literature and invention.

Well, I never  knew this

knew this

about

OXFORDSHIRE FOLK

Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross To see a fine lady on a white horse

The lady in question was LADY CELIA FIENNES, who rode on a white horse from her home at Broughton Castle to Banbury Cross, as part of the May Morning celebrations in medieval times. The original Banbury Cross was torn down by Cromwell’s Puritans and replaced by the Victorians.

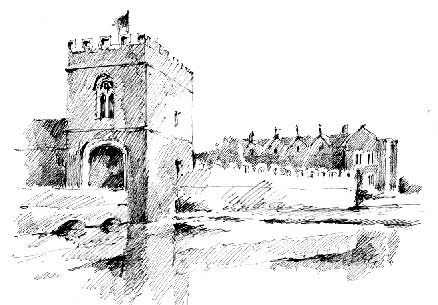

The Fiennes still live at the picturesque moated manor house known as BROUGHTON CASTLE, built in 1300 and enlarged in the 16th century. A present member of the family, SIR RANULPH TWISLETON WYKEHAM FIENNES, belongs to that quintessentially English breed of character, the eccentric English explorer. He completed THE FIRST EVER UNSUPPORTED CROSSING OF THE ANTARCTIC ON FOOT, in 1993.

BANBURY was the model for ‘Candleford’ in Flora Thompson’s trilogy, Lark Rise to Candleford. FLORA THOMPSON (1876–1947) was born and lived not far away at Juniper Hill, which is Lark Rise, and her novel is an account of life in the villages of North Oxfordshire at the turn of the 19th century.

Born in Oxford

Oxford is the home of one of television’s most celebrated detectives, Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse. It also the birthplace of two popular crime story writers, DOROTHY L. SAYERS (1893–1957), creator of amateur sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey, and P.D. JAMES (born in 1920), creator of Commander Adam Dalgliesh.

LENNOX BERKELEY (1903–89), composer.

JACQUELINE DU PRÉ (1945–87), cellist.

STEPHEN HAWKING, theoretical physicist and author of A Brief History of Time, born in 1942.

HUGH LAURIE, comedy actor, born in 1959.

knew this

knew this