Sussex

THE END OF ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND ∗ CLASS ∗ DOMESDAY BOOK ∗ ENGLISH COUNTRY HOUSE ∗ THE WAVES RUSH IN ∗ LAST RESTING PLACE OF THE SAXON ENGLISH

Parham House, a jewel of Elizabethan England.

SUSSEX FOLK

Rudyard Kipling ∗ Richard D’Oyly Carte ∗ Percy Bysshe Shelley

∗ Edward Gibbon ∗ E.F. Benson ∗ Vanessa Bell ∗ Virginia Woolf

∗ Duncan Grant ∗ Enid Bagnold ∗ Vita Sackville-West

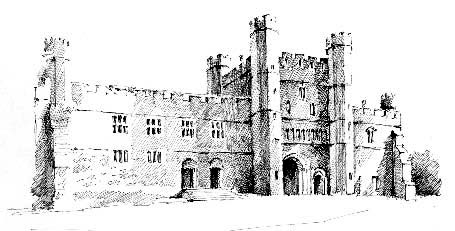

Battle Abbey

On the morning of 14 October 1066, Saxon England, that young, fledgeling ‘land of the Angles’, united and forged with such effort by Alfred the Great and his descendants, was crushed to earth, and Norman England was born. The BATTLE OF HASTINGS, as it became known, was the most important battle in English history and the result changed England and the English for ever.

In 1070 William the Conqueror began building an abbey on the site of the battle, which is in fact some 7 miles (11 km) north of Hastings, both as a celebration of his great victory and a penance for the huge loss of life suffered on that day. The high altar was placed where the Saxon King Harold fell, and although the walls of the abbey church are no more, the foundations are still in place, along with some 13th- and 14th-century remains. To stand where the Saxon army stood, nearly 1,000 years ago, its banners flying in the wind, and to gaze across the valley, now filled with trees, to where the Norman forces were assembled on Telham Hill, is spine-tingling.

English Class

Amongst the most profound effects of the Norman Conquest was the creation of the English class system, which, with a few modifications along the way, has shaped English history ever since. In those days power came from owning land, and so William declared that all land, and hence power, belonged to the Crown. He then handed out parcels of that land to his supporters in return for their loyalty.

The class system that developed was therefore based on the ownership of land. Most of those who owned the land, the upper classes, were French-speaking Normans, while those who worked the land, the working classes, were dispossessed, English-speaking Anglo-Saxons.

This divide was reflected in both accents and vocabularies. While Royalty and the ruling classes used rounded Norman vowel sounds, as in ‘barth’, the working classes used short flat vowel sounds, as in ‘baath’. English words used to describe culture and lifestyle, food, fashion, furniture and titles tend to be French based, while English words of Anglo-Saxon origin are much more direct and earthy and are used for the basics.

For instance, the fact that the working class handled the live animal while the ruling class ate it, is reflected in words used for food, with Saxon words describing the uncooked and Norman words the cooked.

| Anglo-Saxon | French |

| | |

| Cow, Ox | Beef |

| Sheep, Lamb | Mutton |

| Pig, Swine, Ham | Pork, Bacon |

| Calf | Veal |

| Deer | Venison |

(Deer entrails, which were left for the servants, were called ‘umbles’ – hence to ‘eat humble pie’.)

Domesday Book

In order to find out how much land he did in fact now own, William the Conqueror ordered his officials to travel the length and breadth of England and make an inventory of every landholding and settlement in the country, along with its produce and worth. This survey, completed in two years from 1085 to 1086, is known as the ‘DOMESDAY BOOK’ and is THE EARLIEST PUBLIC RECORD OF ENGLAND THAT EXISTS.

Although the Domesday Book was a remarkable achievement, the project was rendered a great deal easier by the fact that the Anglo-Saxons left William a kingdom already efficiently divided into a network of shires that would survive, pretty much unchanged, until the clumsy reorganisation of county boundaries in 1974.

The English Country House

‘England’s most characteristic

contribution to European culture’

CHRISTOPHER HUSSEY

The power that was endowed by the ownership of land came largely from the tenants and rents that went with it. Rent was often paid by working and fighting for the landowner as well as through farming, and the estate required a headquarters from where it could be both administered and defended, in other words, a castle.

In more peaceful Elizabethan times, it was no longer necessary to build fortified houses, and the rich merchants began to build vast palaces that visibly proclaimed their wealth and status. Ownership of a country house was a symbol of the fact that you had arrived, and it became the ambitious Englishman’s most desired possession – as it still is.

In its heyday, English country house living was possibly the most perfect form of existence invented by man – it provided employment, living accommodation, food, and beauty in architecture and landscape that was limited only by the owner’s pocket and his architect’s imagination.

Bosham

While the first Norman King of England went on in glory to shape the land of his conquest, the fate of the last Saxon King of England is less clear. Waltham Abbey in Essex has long claimed King Harold’s body, but there is evidence to suggest that he may never have left Sussex, the kingdom of the South Saxons where he met his doom.

In the far west of Sussex is BOSHAM, a large and outstandingly pretty village overlooking Chichester Harbour, where gardens and mossy lawns are lapped by the muddy green sea, and artists, sailors and wildfowl are lured by the bracing air. Bosham was one of the few settlements to appear in the Anglo-Saxon chronicles, and therefore must have been a place of some importance in those times. St Wilfred of York was known to have established a small monastery at Bosham in the 7th century on the site of an even earlier cell. The fabric of the ancient church contains Roman fragments, Saxon arches and Norman pillars.

KING CANUTE had a palace at Bosham, and it was here that he went down to the water’s edge and commanded the tide to turn back, knowing that it would not, so that he could prove to his fawning courtiers that he was not all-powerful. Canute also met with tragedy in Bosham, for in 1020 his young daughter drowned in the mill stream and was buried beneath the stone church floor.

King Harold’s father, Earl Godwin, made Bosham his home, and Harold later inherited the palace. The Saxon chancel we see in Bosham’s church today is much as Harold would remember it, and appears in the Bayeux Tapestry, where Harold is shown at prayer before embarking on the sea voyage that was to seal his fate. His ship was wrecked on the coast of Normandy and he was taken to Duke William in Rouen, where it is believed he made an agreement to support William’s claim to the throne of England on the death of Edward the Confessor. When Harold returned and claimed the throne for himself, William felt cheated and came to take his due by force.

After the Battle of Hastings some records state that the bodies of Harold and his father were brought back to their home at Bosham. In the 1950s a tomb was found under the floor of the church containing a corpse with the head, right leg and left hand missing – which corresponds to the injuries that Harold had sustained at his death, according to accounts by the Bishop of Amiens.

Could sleepy, seaside Bosham be the last resting-place of the Saxon English?

Well, I never  knew this

knew this

about

SUSSEX FOLK

‘Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.’

‘But that’s another story . . .’

‘For the female of the species is more deadly than the male.’

The quotes above are from the work of RUDYARD KIPLING, THE FIRST ENGLISHMAN AND THE YOUNGEST PERSON EVER TO WIN THE NOBEL PRIZE FOR LITERATURE, who made Sussex his home from 1897 until his death in 1936. From 1902 he lived at Bateman’s, a beautiful 17th-century ironmaster’s house in the village of Burwash, but his first Sussex home was a house called The Elms by the village pond in ROTTINGDEAN, near Brighton, where his aunt Georgina Burne-Jones had a holiday home. She was married to the Pre-Raphaelite painter SIR EDWARD BURNE-JONES, who is buried in the churchyard at Rottingdean. The church itself can boast a set of stained-glass windows made by William Morris to the design of Burne-Jones, considered to be amongst their finest work.

Rudyard Kipling

A frequent visitor to The Elms was Kipling’s friend the society portrait painter SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON, who eventually came to live in The Grange in 1912. He made a woodcut of Rottingdean windmill up on the downs, which was used by the publishers Heinemann as their logo.

Daddy Long Legs

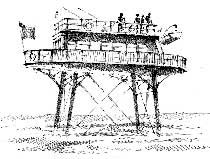

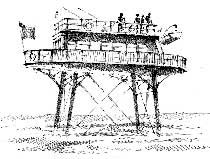

For a few glorious years at the end of the 19th century Rottingdean was linked to Brighton by an imaginative railway dreamed up by Brighton-born MAGNUS VOLK, the BRIGHTON AND ROTTINGDEAN SEASHORE ELECTRIC RAILWAY, affectionately known as ‘Daddy Long Legs’. From a pier at Rottingdean, a tramcar perched on high stilts moved along on rails running under the sea some 100 yards (90 m) offshore, and met up with Volks’s land-based railway on the sea-front at Brighton, opened in 1883 as the world’s first publicly operated electric railway. The Brighton railway is still in action today, but the Daddy Long Legs had to close in 1901, after a slightly precarious career, when Brighton council wanted to build groynes out into the water for sea defence. Lengths of the track bed can still be seen at low tide, along with the stumps of some of the posts that carried the power lines high above the water. Magnus Volk is buried in the churchyard of St Wulfstan’s, Ovingdean, tucked into the hills behind Rottingdean.

Looking down imperiously from the cliffs between Rottingdean and Brighton is ROEDEAN, perhaps the most famous private school for young English ‘gals’ after St Trinian’s. Roedean was founded at 25 Lewes Crescent, Brighton, in 1885 by the Misses Dorothy, Millicent and Penelope Lawrence to provide ‘young ladies’ with an all-round education. The school moved to its present, purpose-built site in 1899. Old girls include the actress Sarah Miles and Dame Cicely Saunders, founder of The Hospice Movement.

RICHARD D’OYLY CARTE (1844–1901), Gilbert and Sullivan’s patron and impresario, is buried in the church at FAIRLIGHT.

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY (1792–1822), poet, was born in HORSHAM.

Writers and Artists Buried in Sussex

EDWARD GIBBON (1737–94), historian and author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, is buried in FLETCHING.

E.F. BENSON (1867–1940), author of the Mapp and Lucia books, is buried in RYE, where his novels are set.

VANESSA BELL (1879–1961), Bloomsbury Group artist and interior designer, is buried in FIRLE.

VIRGINIA WOOLF (1882–1941), Bloomsbury Group novelist, is buried in RODMELL.

DUNCAN GRANT (1885–1978), Bloomsbury Group painter, is buried in FIRLE.

ENID BAGNOLD (1889–1981), author of the classic girl’s story National Velvet, is buried in ROTTINGDEAN.

VITA SACKVILLE-WEST (1892–1962), gardener, poet and novelist, is buried in WITHYHAM.

knew this

knew this