I completely abandoned myself to the Lord.

—Anabaptist martyr, 1527

Amish women are noted for their lovely quilts.1 They symbolize the complex patchwork of Amish culture—the beliefs, myths, and images that shape their world. Symbolic patches of soil, martyrdom, obedience, family, work, and community, stitched together by history, form a cultural quiltwork of Amish life. These patches of meaning, quilted into a single fabric, fill daily routines with significance. Religious threads hold the quiltwork together. Silent prayers before and after meals embroider each day with reverence. Daily behavior, from dressing to eating, is transformed into religious ritual with eternal significance. An Amish farmer’s description of springtime events shows how the patches are woven together in his mind:

Spring is coming to the Pequea when:

horses start to lose their hair

first silo is about empty

milkman is glad it didn’t snow much

folks talking about high mule prices

milk price is coming down

alfalfa and rye fields greening up

you should read John 14–15, Matt. 26–27 and

practice pages 727, 481, 655, 284 in the Ausbund,

you should help your wife move furniture and clean ceilings

grease the harness and plow the garden2

The Amish subscribe to basic Christian doctrines—the divinity of Christ, heaven and hell, the inspiration of Scripture, and the church as the body of Christ in the world today. Yet the practical expressions of Amish faith diverge from mainline Christian churches. Contemporary religious practice is often restricted to brief episodes of life—an hour on Sunday morning, a wedding, or a confirmation. Amish faith has not been separated from daily living; it penetrates their entire way of life. Amish beliefs, worship services, and religious rituals remain virtually untouched by modern influences. Basic Amish doctrines are found in the Dordrecht Confession of Faith, an Anabaptist statement written in 1632, some sixty years before the Amish emerged as a separate group.3 Nevertheless, the Amish emphasize the practice of faith more than doctrinal details.

Although the Amish revise their practical definitions of worldliness in response to social change, their fundamental religious tenets have remained intact over the years. This chapter describes the religious values of Amish culture—the patches of meaning stitched together in their quiltwork. These resources provide the cultural capital that undergirds the operation of Amish society.

Women enjoy the delights of community and artistic expression at a quilting bee.

The solution to the riddle of Amish culture is embedded in the German word Gelassenheit (Gay-la-sen-hite). Roughly translated, Gelassenheit means ‘submitting, yielding to a higher authority.’ Rarely used in speech, it is an abstract concept that carries a variety of specific meanings—self-surrender, resignation to God’s will, yielding to God and to others, self-denial, contentment, a calm spirit. Various words in the Amish vocabulary capture the meaning of Gelassenheit: obedience, humility, self-denial, submission, thrift, and simplicity. In short, Gelassenheit is a master cultural disposition, deeply bred into the Amish soul, that governs perceptions, emotions, behavior, and architecture.4

In Pennsylvania German, the phrases uffgewwe (to give up) and unnergewwe (to give under) best capture the meaning of Gelassenheit. Members are asked to “give up” things and to “give themselves under” the authority of the church. One member said “to give yourself under the church means to yield, to submit.” Baptismal candidates and contrite church members before a confession sit in a bent posture with hand over face, signifying their willingness to “give up” and to “give themselves under” the authority of the church. One member, writing to another one facing excommunication, said, “My heart just bleeds for you, all cause you cannot give yourself up to church rules and those set above you in the church by God” (emphasis added).

Gelassenheit stands in sharp contrast to the bold, aggressive individualism of modern culture. The meek spirit of Gelassenheit unfolds as individuals yield to higher authorities: the will of God, church, elders, parents, community, and tradition. Gelassenheit reveals that Amish culture is indeed a subculture whose core value collides with the heartbeat of modernity, individual achievement. Modern culture tends to produce individualists devoted to personal fulfillment. By contrast, the goal of Gelassenheit is a subdued, humble person who discovers fulfillment in the service of community. In return for giving themselves up for the sake of community, the Amish receive a durable and visible ethnic identity.

The meaning of Gelassenheit penetrates many dimensions of Amish life—values, symbols, ritual, personality, and social organization. “The yielding and submitting,” said one member, “is at the core of our faith and relationship with God.” The faithful Christian yields to divine providence without trying to change or influence history. Gelassenheit is also a way of thinking about one’s relationship to others. It means serving and respecting others and obeying the consensus of the community. It entails a modest way of acting, talking, dressing, and walking. Finally, it is a way of structuring social life so that even organizations remain small, compact, and simple. Like a social equation, Gelassenheit spells out the individual’s subordinate relationship to the larger ethnic community. It regulates the tie between the individual and the community by transforming the energies of the individual into cultural capital. However, rather than pitting the individual against the community, the Amish tend to see the primary tension as being between two social systems: the church, which calls for obedience and self-denial; and the outside world, which exalts individual fame and achievement.5

The early Anabaptists used the term Gelassenheit to convey the idea of yielding fully to God’s will with a dedicated heart—forsaking all selfishness.6 They believed that Christ called them to abandon self-interest and follow his example of suffering, meekness, humility, and service. True Christians, according to the Anabaptists, should not take revenge on their enemies but should turn the other cheek in the face of hostility. They should pray for their persecutors and love their enemies, as commanded by Christ. Self-will obstructs obedience to God’s will. Jesus’ words, “Not my will but thine be done,” became their script of faith. Hence, yielding to God’s will was the test of true faithfulness.

Thousands of Anabaptist martyrs yielded to the sword as the ultimate test of their willingness to mortify self and submit to God’s will. The blood of martyrs seared Gelassenheit into the sacred texts of Amish history. It is not surprising that such a bloody history would leave the indelible print of Gelassenheit on the quiltwork of Amish culture. What is surprising is that the imprint remains vivid, even centuries after the persecution.

Yielding to the right way—God’s way—is the stance of Gelassenheit. Although the Amish rarely use the term in everyday speech, the principle of Gelassenheit orders their whole social system. All things being equal, the higher the cost of joining a group, the more attractive it becomes to its members. In other words, groups that demand very little will not be valued very highly by their members. Amish values of simplicity, humility, and austerity entail personal sacrifice. They provide the cultural capital to build commitment to community and mobilize social capital.

FIGURE 2.1 The Dimensions of Gelassenheit

The nonresistant stance of Gelassenheit forbids the use of force in human relations. Thus the Amish avoid serving in the military, holding political offices, filing lawsuits, serving on juries, working as police officers, and engaging in ruthless competition. Legal and personal confrontation is avoided whenever possible. Silence and avoidance are often used to manage conflict. Indeed silence is an important mode of communication in Amish life.7 A lowly spirit denies luxuries, worldly pleasures, and costly entertainment. Purging selfish desires means yielding to the Plain standards of Amish dress as well as to restrictions on transportation, technology, and home appliances. The submissive posture of Gelassenheit discourages higher education, abstract thinking, competition, professional occupations, and scientific pursuits.

An Amish petition to state legislators concerning a new school law depicts the lowly tone of Gelassenheit: “We your humble subjects . . . do not blame our men of authority for bringing all this over us.... We admit, we ourselves are the fault of it. We beg your pardon for bringing all this before you, and worrying you, and bringing you a serious problem.”8 The yielded person submits to the authority of God-ordained leaders, engages in mutual aid activities, respects the wisdom of tradition, and washes the feet of others in a sacred rite of humility.

Amish attempts to harness selfishness, pride, and power are not based on the premise that the material world or pleasure itself is evil. Smoking, for example, is a common practice among some men, though it is dwindling.9 Sexual relations within marriage are enjoyed. Good food is savored. Recreation, humor, and play, in the proper time and place, are welcomed. Evil, the Amish believe, is found in human desires for self-exaltation, not in the material world itself.

Talk of self-denial defies modern culture, which is saturated with endless dreams of self-fulfillment. Although Gelassenheit seems repressive to Moderns, it is a redemptive paradox for the Amish. They believe that the followers of Christ and the martyrs of old were called to lose their lives in order to save them. The death of Christ redeemed the world, and the sacrifice of the martyrs fertilized the growth of the true church. The Amish believe that people who deny self and submit to divine precepts bring honor and glory to God. Members who yield to their neighbors are ultimately revering God. The person who forgoes personal advancement for the sake of family and community makes a redemptive sacrifice that transforms the church into the body of Christ. Gelassenheit is a social process that recycles individual energy for community purposes, a recycling empowered by the words of Jesus, the blood of the martyrs, and the blessing of ancestors. This deep conviction to yield self-interest for the sake of the community provides a powerful resource of cultural capital.

Etched into Amish consciousness, Gelassenheit regulates the entire spectrum of life from body language to social organization, from personal speech to symbolism. The cultural grammar of Gelassenheit blends submission to God’s will, personal meekness, and small-scale organizations together in Amish life. All of life embodies religious meaning as people place themselves on the altar of community, a sacrifice that brings homage to God. The Amish are urged to “patiently bear the cross of Christ without complaining.”10 Bearing the cross of Christ is not an abstraction, but in the words of one leader, “We wear an untrimmed beard and ear-length hair because we are willing to bear the cross of Christ.”11 Dressing by church standards, raising a neighbor’s barn, cooking for the family, pulling weeds in the garden, forgoing electrical appliances, plowing with horses, and using a carriage are ritual offerings of sacrifice and service to the community—the incarnation of God’s will on earth.

The size and prominence of mirrors in a society signal the cultural value attached to the self. Given concerns about pride and bloated selves, it is not surprising that the mirrors in Amish homes are typically smaller and fewer than those in non-Amish homes. While Moderns are preoccupied with “finding themselves,” the Amish are engaged in “losing themselves.”12 Either way, it is hard work. Uncomfortable to Moderns, who cherish individuality, losing the self in Amish culture brings dignity because its ultimate redemption is the gift of community.

Children learn to “give up” and “give in” at an early age. Parents teach their children that self-will must be purged if they want to become children of God.13 The large size of families teaches young children to wait their turn as they yield to siblings and prepares them for living a yielded life. Amish children are less likely to use first person singular pronouns—I, me, mine, myself, and my—than non-Amish children.14 A personality test administered to children in several settlements found that Amish personality types differed significantly from non-Amish ones. The Amish personality exemplified Gelassenheit: “Quiet, friendly, responsible, and conscientious. Works devotedly to meet his obligations and serve his friends and school . . . patient with detail and routine. Loyal, considerate, concerned with how other people feel even when they are in the wrong.”15

The Amish believe that the quickest way to spoil children is to let them have their own way. Parents and teachers are encouraged to “work together so that bad habits . . . disobedience, disrespect, etc. can be nipped in the bud so to speak.”16 For young children, a spanking may help to stop misbehavior. Children are taught to yield, to wait, to submit. An Amish leader noted: “By the time that the child reaches the age of three the mold has started to form and it is the parents’ duty to form it in the way that the child should go. When the child is old enough to stiffen its back and throw back its head in temper it is old enough to gently start breaking that temper.”17 “Spanking,” said one mother, “is what makes Amish children so nice.” Visitors to Amish homes often remark about the nice and quiet children.

The Amish think the children of Moderns are often spoiled by being driven from club to club and lesson to lesson in hope that they will discover their true selves. In contrast, Amish children are washing dishes by hand, feeding cows, pulling weeds, and mowing lawns. They are learning to lose their selves, to yield to the larger purposes of family and community. JOY, a widely used school motto, reminds children that Jesus is first, you are last, and others are in between. The essence of Gelassenheit is tucked away in a favorite school verse:

I must be a Christian child,

Gentle, patient, meek, and mild;

Must be honest, simple, true

In my words and actions too.

I must cheerfully obey,

Giving up my will and way.18

It would be wrong to conclude that losing one’s self in Amish society is demeaning or dehumanizing. Bending to the call of community does not smother individual expression. The Amish neither wallow in self-contempt nor champion weak personalities. Within limits, creative self-expression flourishes—from quilting patterns to stickers on lunch pails, from gardening to hobbies, from farming to crafts. As in other societies, Amish personality styles, preferences, and habits vary. The constraints of Amish culture would certainly suffocate the “free spirits” of the modern world. But Amish children, taught to respect the primacy of the community, usually feel less stifled by the constraints than Moderns who cherish individuality.

The grammar of Gelassenheit regulates interaction with others. How one smiles, laughs, shakes hands, removes one’s hat, and drives one’s horse signal Gelassenheit or its absence. A boisterous laugh and a quick retort betray a cocky spirit. An aggressive handshake and a curt greeting disclose an assertive self that does not befit Gelassenheit. Rather, a gentle chuckle, a hesitation, and a refined smile embody a yielded and submissive spirit. A slow and thoughtful answer, a deference to the other’s idea, and a reluctance to interrupt a conversation are signs of Gelassenheit. In a small community, individuals know one another well enough that there is no need to “sell” themselves. Thus, the yielded self does not flaunt itself in everyday life. An Amish bishop ended his letter to one of his members with these words: “Remember us in your prayers, for we are likewise minded in weakness. Only me.”

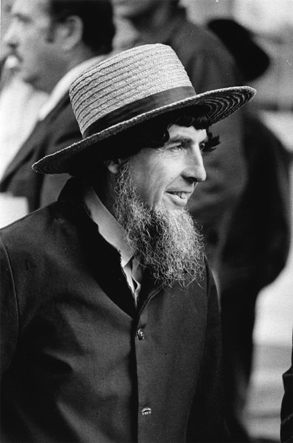

The contented smile of Gelassenheit.

The goal of Amish life is a tame, gentle, and domesticated self—one that yields to the community’s larger goals. But even in Amish society there is room for manipulation. A clever person may learn subtle ways of presenting a “yielded” impression to others for personal gain. A yielded self is especially valued in church life and with elders and others in authority. Men who are assertive and boisterous with outsiders will suddenly become meek and mild in the presence of their bishop. Bold, untamed selves are more likely to flare up with outsiders in business deals, at play, around the barn, and especially among teenagers.

As a master disposition, Gelassenheit also regulates religious experience and practice. In the broader world, religious doctrines are often packaged in theological formulas designed to hold the faithful and convince nonbelievers of the truth. Some formulas imply that one can “find the answers,” “be sure of salvation,” and have “no doubts” about religious faith. In this view, eternal salvation can be achieved by believing and acting properly. This religious logic separates ends from means, for example, “I must be saved in order to achieve eternal life.” Such a calculation assumes that one can decide, that one must decide, and that ultimately one controls one’s own destiny.

It is precisely at this point that Amish faith bewilders those with evangelical religious persuasions. Amish faith is holistic. The Amish resist separating means and ends—salvation and eternal life. They are reluctant to say that they are sure of salvation. They focus on living faithfully while waiting on providence—trusting that things will turn out well. Announcing that one is certain of eternal salvation reveals a haughty attitude that mocks the spirit of Gelassenheit. The faithful, in the Amish view, are called to yield to God’s eternal will and rest in hope that things will turn out for the best. After all, “not everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.” Indeed it is God, the Amish believe, that makes these weighty decisions. Boldly declaring oneself “saved” is a pretentious self-assertion that borders on idolatry in Amish thinking, for only God can make such claims.

Amish ministers talk of “the hope of salvation” and of a “living hope.” Salvation is linked to obedience and faithful practice rather than to belief and emotion. “Feeling and experience is bubble and froth,” explained one bishop. Because salvation is tied to faithful living throughout a lifetime, the Amish hesitate to talk of assurance of salvation. In fact, to say that one is certain of eternal salvation is considered pride. “Humility,” said a bishop, “never exalts itself. Humility never boasts about salvation. There are two ditches along every road, and it’s easy to fall off.”

The code words of the evangelical mind-set—personal salvation, personal evangelism, and personal devotions—accent the individual rather than the community as the center of redemptive activity. In refusing this vocabulary, the Amish bring a much more holistic, integrated view that does not separate the individual from community or faith from action. Evangelical and Amish vocabularies are analogous to two foreign languages describing the same sentiments of love. One is a communal language of patience, humility, community, and practice; the other is an individualistic language of beliefs, certainty, feelings, and experience. Whereas evangelical Christians want to know, control, plan, and act to guarantee their salvation, the Amish outlook is a more modest and perhaps a more honest one.

The Amish view the Bible as a trustworthy guide for living, but they do not quote it incessantly. Those who do so are accused of being “Scripture smart,” for showing off their biblical knowledge. Personal interpretations of Scripture and small group Bible study are downplayed. Individual interpretation of the Scripture is considered dangerous. The Bible is considered trustworthy enough to speak for itself without interpretation. The Scripture is read aloud in church and in family settings where it is heard and interpreted in a communal context. Beyond their religious worldview, social control issues also come into play. Individual interpretations would quickly splinter uniform beliefs and, more importantly, the authority structure of the entire community.

Much is at stake here because this theological understanding undergirds the entire cultural system. A shift toward individual belief, subjective experience, and emotionalism would cultivate individualism and undermine the total package of traditional practices. By linking salvation to obedience and lifelong living, the Amish accent the importance of practicing the traditions of faith. Members are chastised if they attend Bible study groups or fellowship with “born again” Christians who boast of their personal faith and certainty of salvation. One member said it simply, “If you believe in assurance of salvation, you are not Old Order Amish. You are New Order.” Ex-Amish are often quite critical of the Amish emphasis on practice. A former member who joined an evangelical charismatic fellowship said the Amish promote “works and a way of life that makes the Amish religion just that, a religion. In our church we don’t need man-made rules, we just follow the Bible.”

Some religious groups seek to transform or save the world by seeking converts and engaging in missionary programs. Indeed, groups can only grow in two ways: by making converts or having babies. Evangelism is foreign to the Amish. Rather than trying to save the world, they wait on divine providence. In tandem with this, they are surprisingly tolerant of other religious groups. Although firmly committed to their faith, they are reluctant to judge or condemn other people. They yield to the brotherhood, live faithfully in community, and trust that their offering of a yielded self will, in time, be acceptable to God.19

Paired oppositions—obedience and disobedience, church and world, low and high, humility and pride, slow and fast, work and idleness—provide clues to the structure of meaning in Amish consciousness. Abundant throughout the culture, these code words permeate the training of children. Obedience tops the hierarchy of Amish values. Yielded individuals are obedient. Obedience to the will of God is the cardinal religious virtue. Disobedience is dangerous; it signals self-will and, if not confessed, leads to eternal separation from God. The confession for baptismal instruction predicts that the unbelieving, disobedient, and headstrong will receive eternal damnation.20

Obedience to church regulations signals an inner obedience to the will of God. Those who are willing to crush selfish desires will gladly comply with church standards. The belligerent and headstrong, who challenge the order of the church, lack spiritual submission. Various religious phrases and Bible verses are used to underscore the importance of obedience and submission throughout the life cycle.

The Amish emphasize the importance of rearing (die Zucht) a child properly. Childhood training ingrains obedience into daily routines making it a taken-for-granted habit. Learning obedience at an early age is a powerful means of social control. Children are taught from the Bible: “Obey your parents in the Lord for this is right.”21 “Spanking,” said one young mother, “is a given. We start at about a year and a half, and the majority of it is done before they turn five.”

An Amish booklet on child rearing speaks of the “habits of obedience.” The Amish believe that parents should be “ready to punish disobedience,” “insist on obedience,” “allow no opposing replies,” and realize that “if orders are disobeyed once and no proper punishment given, disobedience is likely to come again.” Parents are expected to make children “understand that they must obey you.”22 Retorts and challenges from children, sometimes considered amusing forms of self-expression in mainstream culture, are not tolerated in Amish life. The child obeys the teacher in the Amish school, for “the teacher’s word is the final authority and is to be obeyed.”23 Learning to yield at an early age is a crucial step in preparing for a life of obedience.

Children learn the virtues and habits of work at a young age.

Adult members are expected to obey church rules and customs. A husband and a wife discuss many issues together, but in the end a wife is expected to obey her husband. Deacons and ministers are obedient servants of the bishop. Younger bishops defer to senior bishops. Obedience to divine and human authority regulates social relationships from the youngest child to the oldest bishop, who in turn is called to obey the Lord. To disobey at any level is tantamount to rebellion against God.

These rites of surrender are sacrifices for the larger goal of an orderly and unified community. While expectations for obedience are firm and final, loving concern permeates the social system. A father spanks his child out of love. The bishop expels and shuns a member in “hopes of winning him back.” There are, of course, ruptures in the loving concern, but a tone of reverent obedience governs community life.

Humility and pride frame Amish consciousness. Humility is rooted in biblical teachings. Pride, a religious term for the sinister face of individualism, has its own share of biblical condemnation. An Amish devotional guide says: “Read much in God’s Word and you will find many warnings against pride. No other sin was punished more severely. Pride changed angels to devils. A once powerful king, Nebuchadnezzar, was transformed into a brute beast to eat grass like an ox. And Jezebel, a dominant queen, was eaten of dogs as the result of her pride.”24

The Amish make a sharp distinction between Hochmut (high-mindedness) and Demut (humility). High-mindedness is pride. On a cultural ladder, the Amish equate high-mindedness with arrogance and worldliness. Lowliness reflects humility and weakness—the true spirit of Gelassenheit. Consequently, the Amish speak of “high” individuals and “high” church districts, meaning those that are more worldly and more assimilated into the larger culture. By contrast, low families are the Plainer ones that “hold back” to the traditions of the past. The high and low distinctions are important symbolic boundaries in Amish culture.

A cancerous threat to group commitment, pride elevates individuals above community. Proud individuals display a spirit of arrogance, not of Gelassenheit. The Amish view the proud person as “showing off,” “making a name for himself,” “taking care of herself,” and in all of these ways hoisting him-or herself above others. Proud people “call attention to themselves”; they are “pushy,” “bold,” “forward,” and “always jumping the fence.” A persistent threat to the common good, pride must be rooted out promptly by church leaders, for if left to sprout and grow, it will spread and debilitate the community. “It was pride,” said one minister, “that brought down the world the first time at the Flood.” The Amish cite numerous scriptures that condemn pride—the exaltation of self.

A high look and a proud heart is sin. (Prov. 21:4);

God hates a proud look. (Prov. 6:17);

A proud heart is an abomination to the Lord. (Prov. 16:5);

God resisteth the proud. (Jas. 4:6)

Pride has many faces. The well-known Amish taboo against personal photographs is legitimated by a biblical command: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image or a likeness of anything” (Ex. 20:4). In the latter part of the nineteenth century, as photography was becoming popular, the Amish applied the biblical injunction against “likenesses” to photographs. Their aversion to photographs of individuals was a way of suppressing pride. If people pose for a photograph, they want to exalt themselves and are taking themselves too seriously. They might “think they are somebody.” Such people are obviously “out to make a name for themselves.” With religious sanction, this taboo suppresses individualism and cultivates Gelassenheit.25

The Amish also believe that public recognition of personal achievement erodes humility. Moderns committed to self-advancement eagerly take credit for anything that will enhance their résumés. The legal apparatus of copyrights, credits, permissions, and acknowledgments is designed to assure that individuals receive proper recognition for their efforts. Just as Moderns work hard at earning credit, the Amish work hard at disavowing it. Amish people who yield properly are careful not to make a name for themselves, for that would lead to pride. If recognition comes, it must be modestly shared with others.

Amish writers often write anonymously to avoid attracting attention (pride) to themselves. An Amishman who started using his name at the end of published articles said: “I got my wings clipped and so I just stopped using my name.” An Amishman who published an essay under his name in a local newspaper was disciplined by the church with a six-week probation. Another member, who posed for a photograph to accompany a newspaper story about his use of computers, had clearly overstepped several taboos at once. Scrambling for cover, he took the unprecedented action of sending a letter of apology to a public newspaper. The Amish believe that proud individuals tack their names on everything, draw attention to themselves, and take personal credit for everything. The humble individual, by contrast, freely gives time and effort to strengthen the community and, in the spirit of Gelassenheit, declines public recognition.

The Amish abhor publicity, which is the delight of modern organizations. They leave their public relations to the imagination of outsiders. When Amish achievements do appear in newsprint, names are conspicuously missing. This happened when one Amishman was designated “most improved” dairy farmer of the year. Tagging names on accomplishments turns them into acts of idolatry for human praise and applause. The Bible teaches that “pride comes before a fall,” and in Amish eyes, publicity leads to pride, which may make the community stumble. However, although the Amish deplore public recognition, they warmly recognize and gently praise personal contributions in face-to-face conversation.

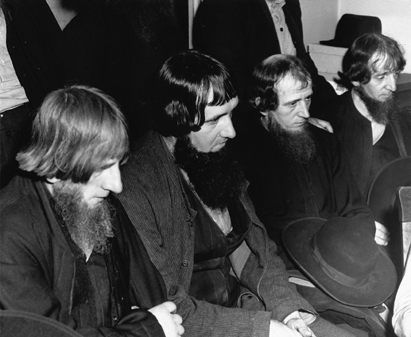

Faced with prosecution for not sending their children to high school in 1953, Amish fathers show the resignation of Gelassenheit in the office of a district magistrate.

The presentation of the self is particularly vulnerable to pride. Vocabulary, dress, and body language reveal a proud or humble self. Modern society provides individuals with an astonishing repertoire of props for making up and presenting a self for every occasion. Hairstyles, clothing, jewelry, cosmetics, and suntans enable individuals to “package” themselves in a multitude of ways. These same tools of modernity, ironically, provide the means of conforming to the latest fads and fashions. The Amish believe that preening rituals, repeated morning after morning in suburban bathrooms, are infested with pride. Self-exaltation is diametrically opposed to the core values of Amish culture. Consequently, all cosmetic props are considered signs of pride, showing off “number one” and scorning the spirit of Gelassenheit. Moreover, the false mask of the “made up” face is seen as a lie, of sorts, that covers up the real face.

In the close interaction of friends and family, the authentic Amish self becomes known and accepted without cosmetic props. Thus all jewelry (including wedding rings and wrist watches) is taboo, because it reveals a proud heart. Any form of makeup, hair styling, showy dress, commercial clothing, flashy color, or bold fabric that calls undue attention to the self is off-limits in Amish culture. Makeup is proscribed, even in the casket. The rejection of outward adornment is rooted in biblical teaching.26

Pride, however, pops up in virtually all avenues of Amish life. Traces of it appear in professional landscaping around houses, showy furniture, fancy harnesses, and windshield wipers on carriages. An artist worried that she was becoming too high-minded, or Hochmut, because of her paintings. One farmer described another as “horse proud,” that is, too concerned about the appearance of his horses. Another man noted, “You can easily tell the difference between the horses and carriages of well-to-do businessmen and everyone else.” Unnecessary trappings are considered pretentious signs that individuals are clamoring for self-attention, elevating themselves above others.

Humility is a barometer of Gelassenheit. The Amish are taught: “If other people praise you, humble yourself. But do not praise yourself or boast, for that is the way of fools who seek vain praise.... In tribulation be patient and humble yourself under the mighty hand of God.”27 Jesus, the meek servant, is the model of true humility. The Amish ritualize the virtue of humility by washing one another’s feet during the fall and spring communion services. According to the command of Christ (John 13:4–7), they teach that stooping to wash the feet of a brother or sister “is a sign of true humiliation.”28 One member, writing to another member facing censure by the church, pleaded, “Humble yourself and stoop low enough so that you can forgive others . . . and make peace with the church.”

Taking their cues from the Bible, the Amish divide the social world into two categories: the straight, narrow way to life and the broad, easy road to destruction. The Amish seek to embody the straight and narrow way of self-denial, while the larger social world represents the broad, easy path of vanity and vice. To the Amish, the term world refers not to the globe but to the entire social system outside Amish society—its people, values, vices, and institutions—in short, to modernity itself. Sectarian groups typically oppose the dominant social order. The Amish contrast church with world, Amish with non-Amish, and “our people” with “outsiders.” A leader put it simply: “If you’re not Amish, you’re English and part of the world.” Even the five-year-old son of an Amish hat maker said: “We sell most of them to our people, but a few of them to the English.” Such a simple division of the social terrain is common even in the modern mind, where capitalism is pitted against socialism, Republican against Democrat, and alien against citizen.

The values of a worldly system that savors individualism, relativism, and fragmentation threaten the spirit of Gelassenheit. The larger social system serves as a negative reference point for perverted values. Daily press reports of government scandal, drug abuse, violent crime, divorce, war, greed, homosexuality, and child abuse confirm again and again in the Amish mind that the world is teeming with evil. Asked one Amish writer, “If we have to read the sickening details of one more war, rape, robbery, murder, riot or famine, or hear the gory report of one more senseless automobile crash, what shall it profit us if we hear of a thousand more?”29 Just as the fear of aggression intensifies American patriotism, so the fear of an evil world strengthens Amish solidarity.

This sharp dualism between church and world crystallized in the sixteenth century, when many Anabaptists were tortured and executed. An early Anabaptist theological statement, written in 1527, underscored the deep chasm between the church and the world: “All of those who have fellowship with the dead works of darkness have no part in the light. Thus all who follow the devil and the world, have no part with those who are called out of the world into God.”30

The split between church and world, imprinted in Amish consciousness by decades of persecution, is legitimated by Scripture. Using biblical imagery, the Amish see the church as “a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a peculiar people . . . who were called out of the darkness” (1 Pet. 2:9).31 The Scripture admonishes them not to “conform to the world” (Rom. 12:2), and to “love not the world or the things of the world” (1 John 2:15). Moreover, “Whosoever . . . will be a friend of the world is an enemy of God” (Jas. 4:4). One Amishman said: “Jesus through his direct plea has commanded us to come out from the world, and be separated, and touch not the unclean things.... In other words, we shall not be conformed to this world, but be transformed.”32

To the Amish, worldliness denotes a whole host of specific behaviors, objects, and lifestyles. High school, cars, computers, cameras, video recorders, television, films, showy houses, and bicycles, all tagged “worldly,” are censured. However, the term worldly is a slippery one, for its meaning evolves over time. White enamel stoves and bathtubs, for instance, were obvious signs of worldliness in the 1940s. Today modern gas stoves and bathtubs are common in Amish homes. Many children and even some adults wear sneakers, which were once forbidden. The term also provides symbolic boundary markers for the Amish moral order. For example, white commercial cigarettes are forbidden but thin “Winchester” cigars in brown wrappers are acceptable.

Pliable over time, the term worldly is a convenient way of labeling changes, products, practices, and beliefs that appear threatening to the welfare of the community. The stigma of this label stalls the acceptance of some products and keeps them at arm’s length. However, not all new things are dubbed worldly. For example, battery-operated calculators, synthetic materials, solid-state gasoline engines, hot dogs, rollerblades, plastic toys, and fiberglass have escaped the stamp of worldliness because they pose little threat to the community.

The Amish fear of worldliness is rooted in a spiritual concern to preserve the purity of the church. The drama between church and world is a battle between good and evil, between the forces of righteousness and those of the devil. It is the ultimate struggle, and to succumb to worldliness is to surrender the community to apostasy. This key unlocks many of the riddles in Amish society. The impulse to separate from the world infuses Amish consciousness, guides personal behavior, and shapes institutional structures. The sectarian suspicion of the world confounds Moderns, who are enchanted by inclusivity, acceptance, diversity, and religious pluralism. If social separation is indeed a by-product of technological progress, the Amish believe they can only preserve their community by separating from the Great Separator, modernity itself.

In contrast to some Moderns who hate their jobs but love to shop, the Amish enjoy their work and despise conspicuous consumption. Theirs is an economy of production, not consumption. Although mischief, play, and leisure flourish in Amish life, work dominates. Often hard and dirty, it is good and meaningful work that for the most part builds community. Amish work integrates; it binds the individual to the group, the family, and the church. Work is not a personal career but a calling from God, and in this sense, it becomes a redemptive ritual.33

Housework, shop work, and fieldwork are offerings that contribute to a family’s welfare. Family, community, and work are woven together in the fabric of Amish life. Work is not pitted against the other spheres of life as often happens elsewhere. The rhythms of work are pursued for the sake of community, not just for individual profit and prestige. A great deal of work is done in small groups, where it blends effort and play in a celebration of togetherness. The profits of Amish work typically support family and church, not exotic hobbies and expensive cruises. Children are expected to “help out” soon after they can walk, and some will learn to drive a team of mules by the age of eight. Because of the communal nature of work, labor-saving technology poses a threat to the social order.

Idleness is deplored as the “devil’s workshop.” If there is any doubt that work is a sacred ritual, there can be no doubt that the Amish despise idleness. They are told: “Detest idleness as a pillow of Satan and a cause of all sorts of wickedness, and be diligent in your appointed tasks that you not be found idle. Satan has great power over the idle, to lead them into many sins. King David was idle on the rooftop of his house when he fell into adultery.”34 Idle minds fill up with vulgar thoughts and become dangerous. An Amishman from another settlement grumbled that the Lancaster Amish “don’t even have time to visit” because “they just work, work, work.” An Amish businessman worries that with more people working in shops, there will be too much free time in evenings and weekends, which will lead to mischief.

An Amishman was vexed by the sloth he saw in a state-funded road crew: “I had the privilege of seeing with my own eyes the total disregard of any work ethic. Eight men and women showed up for the project.... And folks, this was one of the laziest and unmotivated crew of bums you ever saw gathered for a job.” He concluded that it took eight state employees three days to do what three Amishmen could have done in one.35

Amish work is “hands-on,” practical work. Plowing, milking, sawing, welding, quilting, and canning do not involve the manipulation of abstract symbols and data like work in an information society. The farmer or carpenter sees, touches, and shapes the final product and holds responsibility for it. Manual work breeds a pragmatic mentality that values “practical” things and eschews abstract, “impractical” theories derived from “book learning.” Historically, farm life provided abundant work in the context of family, neighborhood, and church. The strong work ethic that provided enormous energy for farming has fueled the dramatic growth of Amish businesses as well.

A consistent theme in the Amish opposition to high school was the fear that academic life would teach Amish youth to despise manual work. The goal of Amish schools is “to prepare for usefulness by preparing for eternity” rather than to spoil children with the abstractions of philosophy.36 Quoting a Bible verse (Col. 2:8), the Amish caution: “Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit after the rudiments of the world and not after Christ.”37 “Children,” according to one leader, “should grow up to be useful men and women, useful in the community and also useful members of the church of Christ.”38

Decorative artwork displayed on walls is disdained because it is not useful and because it encourages vanity. Embroidered family registers, calendars, and genealogical charts are more likely to hang on Amish walls. Some Amish write poetry, keep journals, and decorate crafts with pastoral scenes. Art that exalts the individual artist is unwelcome, although a few folk artists have always found expression in Amish society.39

Practical expressions of art are encouraged in quilting patterns, recipes, flower gardens, artistic lettering in Bibles, toys, dolls, crafts, and furniture designs. The Amish spend an enormous amount of creative energy making crafts for gifts and family needs as well as to sell to neighbors and tourists. Many of the older artistic restraints eroded in the 1990s with the rapid growth of the craft market.40

An Amish quilt shop displays artistic expression. Electric lights are permissible because the property is owned by a non-Amish person.

The artist is always on the fringe of Amish society and needs to work within its moral boundaries, for example, by not painting faces on images of people. Public art shows that call attention to the artist are generally not allowed because they would cultivate pride. One artist complained: “It’s okay to paint milk cans but not to display your work at art shows.” Artistic impulses in their modern forms are considered worldly, impractical, and self-exalting—a waste of time and money. However, church leaders will sometimes grant artists special freedoms to display their work because of disabilities or economic hardships in their families.

When things become too practical and handy, they border on luxury. A hay baler is practical, but an automatic bale thrower to load bales on wagons is considered “too handy” and thus worldly. Automatic devices generally are considered too handy. Sacrifice is a sign of the yielded self, but luxury signals pride. No longer content to work and sacrifice for the common good, the pleasure seeker is preoccupied with self-fulfillment. The Amish are urged to “suffer affliction with the people of God rather than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a season.”41 Pleasure and self-denial, ease and discipline, and fancy and plain are symbolic oppositions that pinpoint the difference between self-enhancement and Gelassenheit.

The yielded self does not seek pleasure, buy luxuries, make things too handy, or pay for “looks.” In the Amish economy rags are recycled into carpets, clothing is patched rather than tossed away with every passing fad, and clothing and toys are passed down to younger children. The exaltation of thrift is not a masochistic drive to win divine favor or guarantee eternal life. It is an acceptance that the habit of austerity—developed over the decades—has produced a wholesome life. In short, it works by stifling vanity and spiking productivity.

One expression of thrift is a strong saving ethic. A financial advisor to the Amish has 750 Amish clients who invest in mutual funds on a monthly basis. The dollars are transferred electronically from their checking accounts to the mutual funds. Some may save as little as twenty-five dollars a month, and others several thousand dollars. Instead of investing in college, young adults often save carefully so they can buy a home or business. One young adult earned $24,000 a year, saved half of it, and in several years bought a small house with virtually no mortgage. Another young man saved $200,000 by the time he was twenty-eight to invest in a farm. A hard work ethic, combined with an impulse to save, an austere lifestyle, and a strong economy, make it possible for some young people to buy property with a very modest mortgage.

Amish culture tilts toward tradition. In the modern world, where new is best and change equates with progress, the Amish offer a different view. They see tradition as a healthy brake that “slows things down.” A young minister noted:

We consider tradition as being spiritually helpful. Tradition can blind you if you adhere only to tradition and not the meanings of the tradition, but we really maintain a tradition. I’ve heard one of our members say if you start changing some things, it won’t stop at some things, it will keep on changing and there won’t be an end to it. We have some traditions, that some people question and I sometimes myself question, that are being maintained just because they are a tradition. This can be adverse, but it can also be a benefit. Tradition always looks bad if you’re comparing one month to the next or one year to the next, but when you’re talking fifty years or more, tradition looks more favorable.

Another Amishman said: “Tradition to us is a sacred trust, and it is part of our religion to uphold and adhere to the ideals of our forefathers.”42

The spirit of Gelassenheit calls for yielding to tradition. Economic pressure, expansion, curiosity, greed, and youthful innovation foster social change. Although suspect, change is not necessarily all bad. New things are not rejected out of hand by the Amish just because they are new. Innovations are cautiously evaluated to see where they might lead and how they might influence the community. Traditional sentiments, however, regulate everything from clothing to education.

Modern societies look forward and strategically plan their future. The Amish glance backward and treasure their tradition as a resource for coping with the present. Tradition slows the dangerous wheel of change. Some entrepreneurs are increasingly looking forward as they plan and strategize to find new markets for their products. Despite these forward glances, the Amish have not lost sight of their past and its precious legacy. While Moderns are preoccupied with planning, the Amish hearken to the voice of tradition. Echoes from previous generations and concerns for future ones merge and enlarge their sense of the present.

Perceptions of time vary enormously from culture to culture. Time organizes human consciousness as well as everyday behavior.43 Anyone stepping into Amish society suddenly feels time expand and relax. The batteryoperated clocks on Amish walls seem to run slower. From body language to the speed of transportation, from singing to walking, the stride is slower. Traveling by buggy, plowing with horses, and going to church every other week create a temporal order with a slower, more deliberate rhythm. Time is marked by half-days and seasons, not by thirty-second commercials and fifteen-minute interviews.

An Amishman described an Amishwoman who had her yard professionally landscaped as “a little on the fast side.” “Fast” families and church districts stretch the boundaries of tradition. The spirit of Gelassenheit is reserved—slow to respond, slow to change, slow to push ahead. An Amishman noted: “Our way of living differs greatly from those living in the fast pace of this world.”44 The Amish separated themselves from the pace of modernity in the mid-twentieth century by not turning their clocks to daylight saving time but following “natural” standard time.45 Although increased interaction with the outside world has led many families involved in business to comply with daylight saving time, other families still follow standard time as a symbolic practice of separation from the world. Church services, of course, usually follow “God’s (standard) time.”

Fast tempos, quick moves, and rapid changes are suspect in Amish culture. The torturously slow tempo of Amish singing in church reflects an utterly different conception of time.46 Holding church services every other week stretches the temporal span of Amish life. The rhythm of the seasons and the agricultural calendar of planting and harvesting widen the temporal brackets and slow the pace of Amish life. These “wide” intervals of time contrast sharply with the abbreviated slices of modern time dictated by news clips, sound bites, and half-hour television programs diced up by commercials.

The great irony here is that in Amish society, with fewer labor-saving devices and technological shortcuts, there is much less “rushing around.” In general, the perception of rushing seems to grow directly with the number of “time-saving” devices one uses. Although much time is “saved” in modern life, for some reason there seems to be less of it. Rushing increases as the number, complexity, and mobility of social relations soar. Thus, the simplicity, overlap, and closeness of Amish life slow the pace of things and eliminate the need for time-management seminars. Visiting, the popular Amish “sport,” is often spontaneous. Drop-in visits without warning are welcomed. There are, of course, planned family gatherings, but spontaneity generally prevails in Amish socializing. Children are sometimes told to “hurry up,” but all things considered, the stride of life is slower.

There are, however, some impending changes. Time clocks, appointment books, and telephones springing up around Amish shops reflect a livelier tempo. Appointments, unheard of in the past, are now commonplace among Amish businessmen, who must synchronize their work with the patterns of the larger society. A “punch-in” time clock in some Amish shops is a sure sign of a new temporal order. Telephones near Amish work sites make it easier to arrange appointments. One person complained: “Now you even have to make an appointment to have your horse shod by an Amish blacksmith. In the past you could just take it there and wait.” Patient waiting, a virtue of Gelassenheit, is now at risk. Moderns, of course, also have moments of waiting and yielding, but they are few. In Amish society, pausing at the yield sign is the way of life.

The social organization and practices of a society constitute an argument about its fundamental values and worldview. The quiltwork of Amish culture is upside down in many ways. The cultural capital and basic values of this community challenge the taken-for-granted assumptions of modernity.47 The implicit arguments flowing from Amish culture contend that:

The individual is not the supreme reality.

Communal goals transcend individual ones.

Obeying, waiting, and yielding are virtuous.

The past is as important as the future.

Tradition is valued more than change.

Personal sacrifice is esteemed over pleasure.

Work is more satisfying than consumption.

Newer, bigger, and faster are not necessarily better.

Preservation eclipses progress.

Local involvement outweighs national acclaim.

Technology must be tamed.

Staying together is the supreme value.

In all of these ways, the Amish have not capitulated to modernity. Their core value system has withstood the torrents of progress. There is, of course, slippage from the ideal of Gelassenheit. Egocentrism, pride, envy, jealousy, and greed sometimes fracture community harmony. This is not heaven. Sin stalks this community as well as others. There are sporadic cases of sexual abuse and drug use. There is pain, suffering, and depression in this community. At times family or church feuds splinter an otherwise peaceful social order. Even leaders sometimes balk when asked to yield to the authority of elder bishops. Business owners in a competitive world find it hard to abide by the spirit of Gelassenheit. Moreover, the conformity to explicit rules cultivates an attitude of hollow conformity among some members who look and dress Amish but have left the community in spirit. After all, this is a human community and these people are people.

Despite aberrations and episodes of self-enhancement, Gelassenheit remains the governing principle, the core value, that solves the riddle of Amish culture. Definitions of worldliness and pride are cautiously updated to permit a slow drift forward. But submission, simplicity, obedience, and humility still prevail. They continue to structure the Amish worldview—a sure sign that Gelassenheit has not faded from the quiltwork of Amish culture.