We’ve had trouble with phones for twenty-five years.

—Amish deacon

Some stereotypes of Amish life imply that they reject technology and live in a nineteenth-century cocoon. Such images are false. The Amish adopt technology selectively, hoping that the tools they use will build community rather than harm it. In short, they prefer technology that preserves social capital, rather than depletes it.

The positive marks of Amish identity—horse, buggy, dress—have their negative counterparts in cars, computers, and televisions. Wary of the impact of certain forms of technology, the Amish have categorically rejected things like televisions and video cameras. In other cases, they have made a distinction between ownership and use. For example, they have been willing to negotiate selective use of telephones, electricity, cars, and other types of technology. The bargaining sessions, stretching over the decades, have produced what appear today as perplexing riddles. This chapter and the following one explore some of these puzzles. Solving them requires a brief historical excursion into the breach of 1910—a turning point in the Amish saga that sets the stage for many of the riddles.

The roots of the 1910 schism go back to the early 1890s. An Amish minister, Moses Hartz Sr., had a son by the same name who became a traveling agent for a milling company. Finding Amish ways too restrictive, the son stopped attending services and, among other things, began wearing pockets on the outside of his coat—a convenience forbidden by the Amish. In April 1895, without the unanimous consent of his congregation, the presiding Amish bishop excommunicated Moses Jr. and placed him under the ban. As an Amish minister, Moses Sr. was expected to uphold church rules. Caught between church and family, he balked and refused to shun his son. After futile efforts by the church to change the father’s mind, he was “silenced” as a minister and, along with his wife, was placed under the ban.1

Eventually the Hartzes were received into a progressive Amish-Mennonite congregation, following a “kneeling” confession. Upon hearing of their confession, Amish leaders called a special meeting and decided to lift the ban. However, a minister who had missed the special meeting was perturbed by the decision. He promptly contacted other Amish leaders and persuaded them to renew the ban. The Amish leaders eventually reversed their decision, and the Hartzes were once again shunned. They remained in social exile for the rest of their lives.2 This action in the late 1890s marked the enforcement of “strict shunning” on members who left the Amish to join similar but more progressive Anabaptist churches. The episode triggered intense debate on the practice of shunning, a discussion that smoldered for twenty-five years, until the bishops reaffirmed the practice in a special statement in 1921.3

The Hartz incident, however, is only a prelude to the real story. The controversy was still brewing in 1909 when electricity and telephones were making their debut. Some disenchanted families had already been dabbling with progressive changes, but the strict enforcement of shunning galvanized their dissent. In the fall of 1909, about thirty-five families, disturbed by the Hartz incident, began holding separate services every three or four weeks for singing and Bible reading. The group petitioned the bishops for a more lenient use of the ban and announced their intention to withdraw if the request was not granted.4 Meeting on 12 October 1909, the Amish bishops denied their request. The splinter group, composed of some eighty-five people, represented about one-fifth of the membership in the settlement at the time. The new group held its first worship service in February 1910 and ordained two ministers in April 1911.5

The progressive faction was eventually dubbed the Peachey church, for it was assisted by two ministers named Peachey from an Amish congregation in central Pennsylvania.6 In contrast to the mild separation of 1877, the breach of 1910 stirred strong emotional feelings. Even some seventy-five years later, an Amish minister dismissed the dissenting group as “just a bunch of hotheads.” Although it followed some Amish practices, the Peachey church adopted new technology more readily than the Old Order Amish. Soon the renegades began using telephones, tractors, and electric lights. They permitted cars by 1928, and by 1930 they were worshiping in a church. In 1950 the Peachey church became affiliated with a larger national body, the Beachy Amish Church. Today six congregations are affiliated with the Beachy Amish Church in Lancaster County.7 They conduct their worship services in English, hold Sunday school, drive cars, and use electricity. The men wear an abbreviated beard, and members dress in Plain garb, although not as Plain as that of the Old Order Amish.

An intriguing aspect of this historical milestone is the contrasting interpretations used by the two factions to explain the schism. Most printed interpretations were written by those on the progressive side, Beachy Amish or Mennonites. These accounts attribute the 1910 split to the strict shunning of the Hartzes.8 An Old Order Amish document verifies that shunning was central in the dispute.9 However, as often happens in oral history, various explanations evolve over time. It is striking that Amish leaders, even seventy-five years later, insisted that telephones and the use of electricity were key issues, or “handles,” in the 1910 cleavage. While acknowledging that shunning was an issue, the Old Order Amish contend that technological changes were the key irritants. Other members suggest that although the telephone may not have been the catalytic factor, the Peachey church began to use telephones at about the same time that the Old Order Amish forbade them. Regardless of the historical facts, the important thing is that the Amish still perceive the telephone as a symbol of the breach of 1910. The division cast a long shadow on the phone and shaped the Amish view of it for many decades.10

The use of telephones has been a contentious issue among the Amish for many years.11 To this day, phones are forbidden in their homes. Why would the telephone—that indispensable modern mouthpiece—be stigmatized as worldly? Why would God frown on a phone?

Invented in 1876, the telephone gradually entered American homes after the turn of the century. But even as late as 1940, only half of Pennsylvania farmers had one.12 Rejecting it early in the century, the Amish have gradually, in the words of one member, “allowed it to creep in and now everybody uses them—well, at least 99 percent!” The phone saga provides a fascinating example of the Amish ordeal with modernity.

Surprisingly, a number of Amish purchased phones as they appeared in rural areas in the first decade of the century. Some early phones were homemade concoctions of lines strung between neighboring homes. An Amish historian estimates that “around 1908 the bishops decided that the phone should be put away and those involved in it just dropped it and tore the lines out.”13

Amish leaders are not entirely sure why the bishops banned the phone, except that they made gossip too easy, were too handy, and were too worldly. Apart from the tag “worldly,” no religious injunctions are cited against the phone. However, its use was never banned. The Amish have readily used a neighbor’s phone for emergencies and have borrowed phones in nearby garages or shops for many years. The taboo against installing phones in houses, however, has held firm since the Ordnung forbade it around 1910.

A complicating factor in the phone decision was the formation of the Peachey church. An Amish minister explained: “A group of people got a bit rebellious and they started to get telephones and this dragged along until 1909.” An Amishman who was thirteen at the time said: “The phone was one of the issues [in the division].”14 Whether phones helped to provoke the division or whether the dissidents installed them soon after they left the Old Order is unclear. What is certain is that the bishops rejected phones about the time that the progressive Peachey church left the Amish fold. And, among other things, some Peachey church members installed phones, which was reason enough for the Amish to permanently outlaw them. When asked about the prohibition, an Amish leader said: “It’s something that’s left over from 1909.” Regardless of the sequence of events, the liberals had adopted the phone, and thus the Old Orders could not accept it again without a severe loss of face. Permitting phones would be a de facto endorsement of the insurgents. In essence, the Peachey church functioned as a negative reference group—a model of worldliness that the Amish hoped to avoid.

To explain the phone taboo solely as an intergroup face-saving ploy overlooks its deeper social meanings, however. The phone is a tool of modernity in both symbolic and substantive ways. It threatened to tie the Amish to the outside world and to erode social capital within. In the words of one analyst: “The telephone was a major means of alleviating the isolation of country life.”15 Lacking automobiles, good roads, electricity, radios, mass media, and regular postal service, many rural areas were insulated from urban influences. The telephone line was the first visible link to the larger industrial world—a real and symbolic tie that mocked the Amish belief in separation from the world. Phones literally tied a house to the outside world and permitted strangers to enter a home at the sound of a ring. Moreover, the telephone was the first form of communication technology available to the Amish—an entirely different order of technology from plows, planters, and other types of productive tools. Thus, in the context of an isolated, rural people, bombarded with new inventions, it was not a thoughtless reflex to dub the phone a “worldly object.”

In a mobile cellular society, the phone connects people continents away, but for the Amish, bonded through face-to-face interaction, the phone posed a threat to internal communication. A phone decontextualizes conversation. It extracts talk from a specific social context where both speakers can observe symbolic codes. Friends can discuss intimate matters on the phone, but such conversations lack the rich nuances of body language, facial expression, and eye contact. In contrast to the spontaneity of face-to-face conversation, phone talk is more formal, abstract, distant, and mechanical. Phone talk conveys disembodied “half messages,” stripped of the symbolic codes of dress and gesture so critical to Amish communication. Young children find telephone conversations baffling because they require greater abstraction than face-to-face chatter. One can only imagine the other speaker’s location, appearance, and context. And one is never sure if the other person is mocking, winking, or, worse yet, doing things to relieve boredom, while giving the impression of listening. In all ways, phone conversations are “half messages” devoid of body language and contextual symbols.

Phone talk is segmented, rational, and impersonal—an idiom of the mechanical language of modernity in form, tone, and structure. Amish who are unfamiliar with phones speak with awkward pauses and uncertain sentences when they call a nurse or physician.16 Phone conversations reflect distant, secondary relationships in several ways. The old adage “It’s easier to say ‘no’ on the phone than in person” reflects the greater social distance and lower accountability of phone conversations.

In Amish society, face-to-face talk and spontaneous visiting are the chief forms of social interaction. They generate social capital. The Amish share death, birth, and wedding announcements as well as everyday news through personal visits. Telephoning reduces visiting. If one can phone, why visit? Although quicker and handier, the phone threatened to erode the core of Amish culture: face-to-face conversations. Thus, the restrictions on phones help to preserve separation from the outside world as well as social capital within.

The ban on phones created problems in times of emergency. In the mid-1930s, several families approached church leaders and requested permission to share a phone. According to oral tradition, they argued that “in case of a fire or something, or an emergency, if someone needs a doctor, there’s no telephone nearby.” They pleaded with the ministers to have a “community phone.” “It was tolerated,” said an Amish leader, “and that was the beginning of the community phone.”

After 1940, community phones gradually appeared. Telephone shanties—which often resemble outhouses in size and appearance—are typically found at the end of lanes or beside barns and sheds. Several families share the phone and its expenses. With an unlisted number, the phone is primarily used for outgoing calls to make appointments and conduct farm business. Loud call bells that amplify the ring are prohibited in some districts to restrict incoming calls. Community phones in public shanties were widely accepted by 1980. But the growing use of phones was not easy. “We had a good bit of trouble with these telephones,” said a bishop. Other members worried that the phone would split the church.

In the mind of one Amish grandmother, telephones were still “on probation” in 1986. Nevertheless, many Amish were calling one another. Friends or business associates scheduled routine times when they were “handy” to receive calls, and “appointments” were often made in advance. The principle of separation from the world was expressed by using unlisted numbers.

The Amish give various reasons for permitting community phones: (1) the lack of nearby non-Amish neighbors in densely populated Amish areas, (2) the embarrassment of farmers dragging barn dirt and smells into non-Amish homes, (3) the need to make appointments with doctors, (4) the need of farmers to call veterinarians and feed dealers,17 (5) the need of businessmen to order supplies, and (6) the need to contact family members living in other settlements or on the outer edge of the Lancaster community.

A businessman places a call in the phone shanty adjacent to his shop.

Over the years convenience, economic necessity, and a sprawling settlement have created ingenious arrangements that brought phones within easy reach. Although still forbidden in homes, telephones are widely used today. Church districts vary on the placement of phones in shops and barns. Districts in the conservative southern end have a stricter policy on phones. But in the heart of the settlement, with shops galore, telephones abound. Many farmers have a private phone in the barn, tobacco shed, or chicken house, usually tucked away from public view. Lacking a radio, some farmers routinely call the national weather service for forecasts every morning.

The strongest pressure for phones comes from business owners. Some bishops permit phones inside shops, but many require adjacent telephone shanties. Sometimes the caller can literally reach through a window to use the phone. By the turn of the twenty-first century, many entrepreneurs were printing phone numbers on their business cards and brochures, an unheard of practice only a few years earlier. A successful businessman who uses a state-of-the-art electronic cash register explained why he does not have a telephone: “The bishop said that he’d really rather that I didn’t have one if it’s just for the sake of convenience, unless I have to. So I use a neighbor’s answering service since [a phone] isn’t really necessary and since the bishop is on top of the list of the people that I respect.”

A growing number of families have private phones outside their homes. An Amish family living in a double house rents a phone from their “English” neighbors on the other side. Many people have a phone in a shanty adjacent to their home, shop, or barn. Two single sisters living in a small village installed one in their small horse barn. One person said her uncle has a hidden one in his home, and “his father would turn in his grave if he saw it.” Although the phone remains outside the home, many families now have one on their property. Indeed, in the words of one Amishman, “Community phones are history.”

By the turn of the twenty-first century, heated discussions focused on the use of answering machines, voice mail, fax machines, and cell phones as well as the installation of phones in offices. Although church elders frowned on answering machines because these required electricity, they were lenient with voice mail provided by the phone company. The church discourages cell phones, but many contractors use them to coordinate mobile work crews on several jobs. In fact, one person said, “Cell phones are springing up everywhere.” The church has steadfastly maintained its taboo on phones in private homes, but that line is difficult to enforce with the portability of cell phones, which makes them especially troublesome.

Apart from the historic forces that shaped the interdiction against phones, present-day explanations for banning them from homes hinge on two issues: separation and community integration. The Amish believe that a home phone separates but that a community phone integrates. When asked why the Amish are afraid of the phone, one member said: “If you have a phone in the house and you have growing children, as they get older, why then you’re going to have one child who wants one up in her bedroom and the other one who wants an extension in her bedroom and it just goes on and on and it separates the whole family” (emphasis added). A grandfather explained: “If you have a place of business and need a phone, it must be separate from the building, and if it’s on the farm it must be separate from the house. It should be shared with the public so that others can use it. It’s just not allowed in the house, where would it stop? We stress keeping things small and keeping the family together” (emphasis added).

Some men contend that with phones in homes women would “waste a lot of time in endless chatter.” A businessman described the practice as a buffer against interruptions: “If we had a telephone up there in the shop, I would just be bothered all the time. I just don’t want any up there. It needs to be separate from the building.” Said one mother, “A phone in the house would just be a nuisance.”

The Amish do not consider the phone a moral evil that will lead to eternal damnation. Their question is “If we ‘give in’ on the phone, what will be next?” They have a good grasp of the social consequences of the phone for family life—gossip, individuation (multiple phones), and continual interruptions. A ringing phone would spoil the natural flow of family rhythms. The Amish worry that phones would pull families apart by encouraging attendance at meetings, scheduling appointments, and spending less time together. Phones not only permit unwanted visitors to intrude into the privacy of a home at any moment, but they also impose a technological structure on the natural flow of face-to-face interaction.

The phone deal that the Amish negotiated is an ingenious arrangement. They have agreed to exclude it from homes, while allowing limited use for commercial purposes. The bargain incorporates key understandings in the fine print: (1) It upholds the historic taboo and thus keeps faith with tradition. They can say, “As always, we don’t approve of home phones.” (2) It saves face with the splinter group of 1910 by demonstrating that the Amish have not drifted into the worldliness of the liberal churches. (3) It preserves the natural rhythms of face-to-face interaction in home and family. (4) It encourages cooperation through the use of community phones. (5) It permits the development of small industries that are critical for the economic viability of the Amish community. (6) It symbolizes key Amish values—separation from the world, establishing limits, shunning convenience, preserving family solidarity, and respecting past wisdom. (7) It controls technology. These understandings keep the phone at a distance and limit its use. The Amish are its master rather than its servant.

The phone story is an intriguing parable of human interaction with technology—a demonstration that technology can serve the community without dominating it. The inconvenience of walking to an outside phone or taking messages from an answering service is a daily reminder that membership in an ethnic community exacts a price—a reminder that things that are too handy and too convenient may lead to sloth and pride. The phone agreement is a way to uphold tradition and absorb change, to appease the traditionalists as well as the entrepreneurs who need phones for economic survival. It is a deal that allows the Amish to have their cake and eat it too—preserving tradition while bending to economic pressures.

Electricity is conspicuously absent from Amish homesteads. Newer Amish homes with contemporary decor have pleasant kitchens and modern bathrooms. But electrical appliances—microwaves, air conditioners, hair dryers, dishwashers, toasters, mixers, blenders, can openers, electric knives, TVs, VCRs, CD players, and computers—are missing. Bottled gas is used to heat water and to operate modern stoves and refrigerators. Homes, barns, and shops are lit with gas-pressured lanterns hung from ceilings, mounted on walls, or built on mobile cabinets that hold pressurized tanks of gas.

The Amish use electricity in several ways. Flashing red lights on the back of buggies warn approaching traffic. Electric fences keep cattle in pastures. The milk in bulk tanks is stirred by electric motors. Battery-operated alarm clocks buzz before dawn. The elderly read by small, battery-operated lamps. Electric welding machines abound on Amish farms. Carpentry crews use electric power saws at construction sites. Battery-operated tools fill many shops. The solution to this baffling maze of electrical use is found in tradition, intergroup relations, economic pressure, and conscious decisions to avoid worldly entrapments. A brief overview of electrical usage in the larger society sets the stage for the Amish story.

The Edison Electric Company began operations in Lancaster City in 1886. Arc lights soon illuminated streets, and some six thousand incandescent bulbs were eventually burning in homes and businesses. From 1890 to 1900, hotels and businesses used electric motors for power, and soon electric trolley cars were replacing horse-drawn “buses.”18 But for the most part, electricity stayed within city limits in these early years. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, power lines gradually crept into the countryside along major roads. Some outlying towns began operating their own power plants, but many rural areas still relied on kerosene lamps. In 1924, only 10 percent of non-Amish farms had current for lights and appliances. By 1930, there were 10,000 private electric plants on farms, but most Pennsylvania farmers still milked by lantern light.19

Several types of electrical services had emerged by the 1930s. First, cities and boroughs had independent generating plants. Second, many farms and businesses in rural areas operated small Delco or Genco electrical plants. These private plants provided homeowners with electricity from batteries charged by a generator powered by a gasoline engine. Third, farms along main roads began hooking up to public power lines as they gradually became available. Finally, many remote areas remained in the dark. By 1946, however, 80 percent of the non-Amish farmers were using electricity.

Although the Amish hedged on using electricity from public utility lines, they had been using batteries for many years. Batteries were used to start gasoline engines that powered washing machines, water pumps, and feed grinders. Flashlights were also acceptable. Batteries were self-contained and unconnected to the outside world. They were handy but not “too handy,” and they posed no threat to the Amish community. However, the church soon began to frown when light bulbs were hooked to batteries.

With a gasoline engine for power, Amishman Isaac Glick rigged up a generator with an electric light in about 1910.20 He used the light to check the fertility of eggs in his hatchery business. The church, without a firm policy on electricity, did not censure Glick’s light. Several years later, Glick’s sons used batteries to hook up a light in their barn. One son stated: “The church ‘got wind of it’ and Father was brought to task in a church counsel meeting. After that, Daddy didn’t want us to use the light.” However, other Amish farmers were lighting their horse stables with bulbs connected to batteries without incurring the church’s wrath. Thus, prior to World War I, the Amish attitude toward electricity was still in flux.

The menacing shadow of the 1910 division hovered over the Amish once again as they coped with the use of electricity. Indeed, the split in 1910 made it easier for the Amish to address the issue because the progressive Peachey church welcomed electrical innovations. Its members installed small Delco plants and generated their own electricity for lights and motors. An Amish minister described the electrical taboo: “An order was established that was not changed until the bulk milk tanks came in the late 1960s. The Peachey church had it [electricity], and that just about ruled it out for us.” Once again, like the telephone decision, the readiness of the liberal group to welcome electrical lights helped the Amish say no.21

As the Peachey church accepted electricity, the Old Order position began to gel. Three incidents in about 1919 hardened the Amish policy. A tinsmith known as “Tinker” Dan Beiler ran some of his power tools with a gasoline engine. An inventive Amishman, he rigged up a light bulb whose brilliance flickered with the speed of his generator. Community folks—Amish and non-Amish alike—often stopped by to see the contraption. One person noted: “He didn’t really need the light for his tinsmith business. He was a tinkerer, and he liked to tinker with the light.” Ben Beiler, an influential Amish bishop, was not amused. He did not mind if “Tinker” Dan tinkered with his tin, but tinkering with a light bulb was taking things too far. The bishop’s “no” was firm. Unwilling to yield, “Tinker” Dan soon packed up his light and moved to Virginia.

At about the same time, Ike Stoltzfus, who lived a few miles down the road, bought a Genco electric plant for his greenhouse business. An electric water pump provided a steady supply of water for his vegetable plants. According to one account, Bishop Beiler “just clamped down on him without taking it up with the church. Ike didn’t know it was wrong, but the bishop, in his mind, thinks this member here was always kicking over the traces and his attitude isn’t too good toward the church and we just can’t tolerate this. So they gave Ike several weeks to get rid of it.” And he did.

Another member, Mike Stoltzfus, used electrical power tools for repairs in his carriage shop. According to one informant, Bishop Beiler said, “‘This may not be.’ He was just not going to have any of this stupidity.” So Mike got rid of his electric tools. A former member said Bishop Beiler “was very influential on this electric question, in setting the direction, definitely. With another bishop it might have gone a different direction. It probably would have.” In any event, the Amish taboo on electricity solidified.

The Peachey church’s use of electricity and Bishop Beiler’s influence were not the only factors involved. Electricity provided a direct connection to the outside world, and to practical-minded rural people, electricity was mysterious. Where did it come from? Where would it lead? The fear was articulated by an Amish farmer: “It seems to me that after people get everything hooked up to electricity, then it will all go on fire and the end of the world’s going to come.” For a people trying to remain separate from an evil world, it made little sense to literally tie one’s house to the larger world and to fall prey to dependency on outside power.

Fearing an unholy alliance with an evil world, steering a careful course away from the Peachey group, and bearing the imprint of a strict bishop, the electric taboo became inscribed in the Ordnung by 1920. One member recalled: “The church worked against it when electric first came and set a tradition, and it just stayed a tradition up to today.” The tradition that crystallized about 1920 permitted the continued use of electricity from 12-volt batteries. Higher voltage electricity, tapped from public power lines or generated privately by a Delco plant, was forbidden. Electric light bulbs were taboo as well. As before, batteries could be used to start motors and power flashlights. So in essence, the decision was not a new decree; it was merely an attempt to uphold customary practice, to set a limit, until the Amish could see where the new electrical trends might lead. The distinction, however, between 12-volt direct current (DC) stored in batteries and 110-volt alternating current (AC) pulled from public lines became a critical difference over the years as standard electrical equipment became dependent on 110-volt current.22

Reflecting on the church’s decision to limit the use of electricity, a member said: “Electric would lead to worldliness. What would come along with electric? All the things that we don’t need. With our diesel engines today we have more control of things. If you have an electric line coming in, then you’d want a full line of appliances on it. The Amish are human too, you know.” Another person noted: “It’s not so much the electric that we’re against, it’s all the things that come with it—all the modern conveniences, television, computers. If we get electric lights, then where will we stop? The wheel [of change] would really start spinning then.” “Electric is just not allowed,” said one member, “because it’s too worldly. Air power is better because it’s privately owned.” And according to one bishop, using electricity would simply mean “hooking up with the world too much.”

In 1920, Bishop Beiler had no inkling of the avalanche of electrical appliances that would sweep across society in the following years. The taboo on 110-volt electricity conveniently preempted debate over each new gadget and eliminated them from Amish life. Banning electricity was an effective means of keeping the world at bay—literally and symbolically.

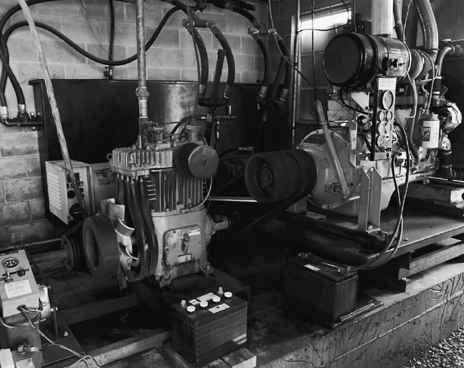

Diesel engines are used to operate air and hydraulic pumps to power equipment on Amish farms and businesses.

Amish farm equipment changed rapidly in the 1960s as horse-drawn machinery became more difficult to buy. To replace worn-out equipment, Amish machine shops began converting tractor-drawn machinery to horse-drawn in a backward technological step. Electric welders, an important tool in this process, were also used to repair broken machinery. Portable electric generators, powered by gasoline engines, could produce the powerful electricity needed for welders. Amish farmers and mechanics gradually began using portable generators and welders, clearly breaking the 12-volt tradition. Given the compelling need to adapt farm machinery for use by horses, the bishops looked the other way. But the mechanics who began using electric generators for welders were tempted to use them in other ways as well.

Testing the rules of the church, some farmers began plugging home freezers and other electrical motors into their generators. Some even hung light bulbs in their barns. Worried about where this trend might lead, ordained leaders condemned the generator in a special series of ministers’ meetings in the early 1960s, with one exception—it could still be used to operate electric welders to repair farm machinery. Asked about the use of generators for welders, a farmer said: “Our bishops are sometimes pretty hard pressed. They don’t know where to draw the line. Now the welder’s a piece of machinery that was allowed. They said it is something that we can have, it is almost necessary to keep our equipment running and that sort of thing.” Allowing generators to be used for electric welders enabled Amish farmers to convert tractor-drawn equipment for use by horses. It was better to permit selective use of generators than to lose the horse altogether.

The electricity issue returned again in 1968. To improve sanitation and reduce hauling costs, milk companies began requiring dairy farmers to store and chill milk in large stainless steel tanks instead of in old-fashioned milk cans. Bulk storage tanks, powered by electricity, could hold a ton or more of milk. Amish farmers had already been chilling their milk in cans in mechanical coolers powered by diesel engines, but the bulk tank edict placed church leaders in a quandary. The dairy industry was booming in the 1960s. Amish herds with a dozen cows were doubled and sometimes even tripled. Milk prices were good. The diversified farming of the past was giving way to specialized farming. Amish farmers were using mechanical milkers, and the monthly milk check was becoming the prime source of income for many families.

In 1968 Amish farmers received a series of letters spelling out the stark ultimatum: install bulk tanks or lose the market for your milk. The tanks required electricity. Amish leaders were caught in a dilemma. If they banned the tanks, many members might lose their prime source of income: some would be forced to quit farming altogether, and others would sell their milk for cheese and take a financial loss. Rejecting the bulk tank might encourage young farmers to leave the church or force them to take factory jobs, placing the family farm in jeopardy.

An Amish farmer summarized the impasse: “The milk companies said we had to get bulk tanks or lose our milk market. Milk was our most important income and so we tried to keep it. The bishops had a hard line to draw so that farmers could make a living off the family farm, but yet not get too big and go in debt or go for government financing. We didn’t want electric or to have to tap into public lines.” If the bishops took a hard line on bulk tanks, they might annoy enough members to trigger a new division—something they surely did not want two years after the schism of 1966. And yet the bishops could not capitulate to modernity by overturning tradition and using public power lines. They could not rescind their recent taboo on electric generators. If they did, history and the Lord himself would never forgive them; moreover, how would they ever control the use of electricity with all its complications?

Although the milk companies pressed the issue, they also needed milk from Amish farmers and thus were willing to negotiate. In a series of three delicate meetings, a settlement was chiseled out between the stewards of tradition and the agents of modernity. Five senior bishops and four milk inspectors negotiated the deal in an Amish farmhouse. The senior milk inspector, who spoke the Amish dialect, called the meeting. He said in retrospect: “We had a long battle with them, but we didn’t want to lose them.”

The milk inspectors and the moral inspectors dickered over a variety of issues. First, how would the tanks be powered? That was easy. The Amish were already using small diesel engines to operate mechanical coolers to chill their milk in cans. The refrigeration units on the bulk tanks could also be operated by a diesel engine. Running the diesel twice a day would power the vacuum milking machines as well as run the refrigeration unit. This was acceptable to the milk inspectors as long as the diesel engine was outside the milk house. Second, the milk inspectors insisted that the milk be stirred by an agitator five minutes per hour to prevent cream from rising to the top, inviting bacterial growth. Additionally, the inspectors demanded that the agitator be operated by an automatic switch, which placed the negotiators at loggerheads.

There were two problems for the Amish. First, the word automatic sounded too modern, too convenient, too fast—downright worldly. Second, an automatic agitator required 110-volt electricity. Small generators could be installed on the diesel motors to provide 110-volt current for the agitator; however, the generator had been restricted to welders just a few years earlier, and it would require swallowing a great deal of pride to erase a decision so recently engraved in the Ordnung. Moreover, having a generator in every Amish diesel shed would open the door to other temptations. Ingenious farmers might start plugging a host of other gadgets into their generators—fans, cow clippers, radios, televisions.

A 12-volt motor stirs the milk in this bulk tank, but lanterns illuminate the milk house and cow stable. The mobile “sputnick,” lower right, is used to bring the milk from the cows to the bulk tank.

The milk inspectors would not budge on the automatic agitator. Nor would the Amish on the use of generators. Was there no escape from this dilemma—no way to prevent an economic disaster and also maintain faith with tradition? Could the agitator be powered by a special 12-volt motor rigged up to a battery? The Amish reluctantly agreed. They could live with the automatic starter, but only if it was powered by a 12-volt battery. And so a deal was forged. The bishops would accept bulk tanks if their refrigeration units were powered by diesel engines. They also agreed to automatic agitators run by a 12-volt battery, recharged by small generators.

There was one more snag. The milk companies planned to haul the milk in large tank trucks every other day. Thus, they would collect Amish milk on every other Sunday. In the past, the Amish never shipped their milk on “the Lord’s Day.” An automatic electric starter was one thing, but shipping milk on Sunday was an unthinkable profanity. The Amish “no” was adamant! It was the milk companies’ turn to concede, and concede they did. When asked if the milk companies considered dropping the Amish because of Sunday pickups, the head inspector said: “We never took it that far because we needed the milk. When you need it, you can’t bargain too much. You can bargain, but you can’t put too much pressure on.” So at great inconvenience, plus the cost of overtime pay and extra miles, bulk tank trucks arrive at Amish farms on Saturday, or very early Monday morning.

The tank deal of 1969 was an ingenious settlement for the Amish as well as for the milk inspectors. The family farm could survive without using 110-volt electricity from public power lines. Moreover the Lord’s Day would not be tarnished with Sunday milk pickups. Both religious tradition and economic vitality had been preserved. A few bishops were unhappy with the modern trend, but most Amish farmers quickly installed bulk tanks, stabilized their economic base, and thus preserved the family farm. The basic arrangement continues today. Small generators, run by diesel, recharge 12-volt batteries, which power the bulk tank agitators on the tanks.

Despite these efforts to stay on the farm, land was becoming scarce and expensive. So in the 1970s some Amish began working off the farm. Carpentry was a traditional and safe choice, but carpentry crews also needed power tools for commercial work. Reluctantly, portable generators were permitted so that mobile carpentry crews could operate electric tools at construction sites. In addition, carpenters working at construction sites with electricity were allowed to tap into public lines. On the farm, however, the generator did create new temptations. One farmer said: “If you got in a pinch, it might be necessary to use electric to clip cows or debeak chickens, as long as no one happened to be watching.” Other farmers found it convenient to “get in a pinch” in other ways. Some ran their hay elevators and other small motors with 110-volt current from the generators until “the bishops really tightened up on these devious uses of the generator,” according to one young farmer. In cases of special need, the regulation is relaxed. For example, a family with an asthmatic child needed 110-volt electricity for an oxygen pump, and they were happily granted the use of a generator.

The present “understanding” of the Ordnung on electrical usage is fivefold. First, 110-volt current from public utility lines is forbidden, as always. Second, battery-supplied 12-volt current is acceptable for a variety of uses: fence chargers, cow trainers, agitators for bulk tanks, calculators, adding machines, reading lights for the elderly, hand-held drills and small motors to operate equipment in shops. Third, generators are permitted for welders, bulk tanks, and the electrical tools needed by mobile construction crews. Generators may also be used to recharge batteries for a variety of uses. Fourth, 110-volt current for uses other than welders and carpentry tools is forbidden. In several cases computers, appliances, and motors using 110-volt alternating current that were operated directly from generators had to be “put away.” Fifth, inverters are widely used. They gradually came into use in the 1980s and 1990s, but that interesting story requires a telling of its own.

The inverter became available in the late 1970s. This small electrical gadget—the size of a car battery—could convert, or invert, 12-volt current into “homemade” 110-volt current. The trail of electricity thus goes from diesel to generator, to 12-volt battery, to inverter, and finally to a typical 110-volt appliance, bulb, or motor.

This fascinating circumvention symbolizes the delicate tension between tradition and modernity. A 12-volt battery provides the electricity for the inverter, which is certainly within the spirit of the 1920 taboo. Yet the inverter, in turn, produces “homemade” 110-volt current, which can run electronic equipment—cash registers, soldering guns, digital scales, calculators, copy machines, typewriters, and other small gadgets. The inverter brings temptations because toasters, TVs, CD players, computers, and light bulbs can also be plugged in. But because the inverter depends on a 12-volt battery, it severely limits the number and size of appliances that can be attached, and the battery must be periodically recharged. In Amish culture such limits are welcomed. Inverters are primarily permitted in shops and businesses, not homes.

Asked what the difference is between electricity coming directly from the generator or coming from an inverter via a battery, an Amish businessman replied: “It’s more acceptable from a battery, but it does the same thing in the end. A generator produces electricity, pure electricity, and really, I guess an inverter after the battery also produces electricity but it is in a different sense, in a different form. If we were to allow generators across the board, then we would have our own electricity right off and then everything, everything, deep freezers, lights, and the whole bit.”

Inverters are widely used by businesses, but the use varies somewhat by church district and the disposition of the local bishop. On this issue, there is a good deal of polite looking the other way. If inverters are used to operate computers, televisions, and popcorn poppers, they will challenge the limits and may have to be “put away.” For the moment, at least, they remain an ingenious bargain that permits electric cash registers in retail stores while respecting Amish tradition. Such cultural compromises perplex those who appreciate neither the importance of tradition nor the fragile base of a peaceful community.

The distinction between direct current stored in 12-volt batteries and 110-volt alternating current tapped from public utility lines sounds absurd to Moderns. When the Amish church distinguished between batteries and higher voltage electricity in 1920, they were merely drawing a safe line. The long-term implications of their distinction were unknown, but in the wisdom of their ignorance, the ban on high-voltage current became a useful way of regulating social change. To a young Amish farmer, it makes sense to draw the line at 12-volt direct current: “You are really limited, you know, with 12-volt direct current. You can’t go and put in a television or something like that because you don’t have enough current, unless you hook up dozens and dozens of batteries. If you have alternating current, your 110, there is no limit to what you can do. You can get yourself a hair dryer, if you want to. You really don’t have anything to keep you from doing it, either. Because if you can have a coffeepot, who says you can’t have a hair dryer?” So over the years, limiting electrical use to 12-volt current became a practical way of arresting and controlling social change.

TABLE 8.1

Telephone and Electrical Guidelines

As in many other issues, the Amish make a firm distinction between use and ownership. Amish farmers renting a farm from a non-Amish neighbor are permitted to use electric lights in the barn and house. However, the wiring is torn out if Amish purchase the property. A quilt shop owner renting from a non-Amish neighbor may have lights in a showroom. An Amish family buying an English home has a year to tear out the electrical wiring. One Amishman, hopeful that the church would eventually accept the wider use of electricity, placed conduits throughout his newly constructed house. But so far his hopes have been in vain.

As small industries sprang up in the 1970s, they required heavy power tools in order to be competitive. Diesel engines could operate large drill presses and saws from their power shaft but not lathes, jig saws, grinders, and metal punches. The church doggedly forbade the use of electricity from public utility lines, so Amish mechanics explored other alternatives. They discovered that electrical motors on shop equipment could be replaced with hydraulic or air motors. Hydraulic and air pumps, powered by a diesel engine, could then force oil or air under high pressure through hoses to power the motors on grinders, drills, and saws. The use of hydraulic and air pressure was quickly dubbed “Amish electricity.”

An Amish shop owner chortled: “We can do anything with air and hydraulic that you can do with electricity—except operate electronic equipment.” Today state-of-the-art saws, grinders, lathes, drills, sanders, and metal presses, powered by air or hydraulic pressure, stand in Amish shops. Once again, tradition triumphed. This new technology allowed the Amish to modernize while retaining their historic ban of public power lines and 110-volt current. Today Amish businesses have all the power they need to operate modern equipment and remain competitive. As long as televisions and computers cannot run on air pressure, air and hydraulic is a safer option than the inverter. Many families also use “Amish electricity” to power water pumps, small machinery, washing machines, sewing machines, and food processors. Indeed, hydraulic water pumps have rapidly replaced windmills on many farms. An unwritten understanding of Amish culture says: “If you can do it with air or oil, you may do it.” “Amish electricity” has enhanced economic growth, ethnic identity, and symbolic separation from mass society. This remarkable deal simultaneously preserves tradition and permits progress.

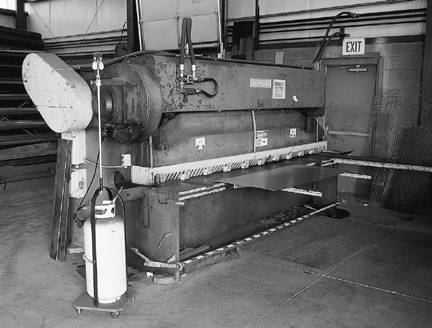

This large machine, powered by hydraulic pressure, bends and cuts sheets of metal. The mobile gas-pressured light, on the left, helps to illuminate this welding shop.

The advent of home freezers in the 1950s offered a better way to preserve garden produce for large Amish families. But freezers required electricity. A few freezers, in fact, were operated by electricity from on-site generators in the early 1960s. However, leaders feared that allowing freezers in homes would make it too easy to plug televisions, radios, and all sorts of appliances into electrical outlets. Thus, the freezer was banned in 1966, not because the Amish view it as evil, but because other worldly devices would have likely followed it into Amish homes.

However, most Amish families do have access to a freezer. Many rent small storage freezers located in fruit markets or stores. Other families own a freezer in a non-Amish neighbor’s garage or basement. The Amish family may contribute to the electrical costs or barter services or garden produce in exchange for the neighbor’s hospitality. At first glance, the practice of keeping freezers at nearby non-Amish homes appears hypocritical. However, rather than two-faced deviance, this arrangement is but another compromise. It permits the use of a modern appliance to preserve food, which supports self-sufficiency, the extended family, and labor in a family context. At the same time, the arrangement bars other electrical gadgets from entering Amish homes. The freezer riddle keeps technology at a distance while still using it to preserve the family garden and self-sufficiency.

The compromises emerging from Amish history point to several conclusions: (1) The taboo on electricity was a literal way of separating from the world and maintaining self-sufficiency—an independence that is still preserved today. For instance, the Amish are less threatened by power shortages caused by storm, disaster, or war. (2) The taboo on electricity also created a symbolic separation from the world, a daily reminder that “we are different.” (3) The rejection of electricity provides a symbolic bonding that unites the community internally. (4) The Amish policy on electricity implies that community wisdom, not individual fancy, must govern its use. In other words, individuals cannot be trusted with such powerful technology. (5) The 1920 rejection of high-voltage electricity conveniently slowed social change by eliminating new electrical appliances and machinery that appeared in the twentieth century. (6) By avoiding rancorous debate over each new technological item, the Amish were able to preserve communal harmony. Apart from the bulk tank and the welder, the big decision on electricity preempted a host of small debates over hair dryers, shavers, coffeepots, and so forth. (7) The proscription against electricity effectively quarantined the Amish from outside electronic media—radios, televisions, record players, CD players, and computers. Curtailing such external influences is crucial for the preservation of Amish values. (8) The concessions on electricity have been driven primarily by economic concerns. Although it benefits the whole community, the use of air and hydraulic power has facilitated the work of men more than that of women. (9) Sacrificing electrical conveniences is a daily reminder that individual desires must yield to larger community goals.

Electric cash registers are powered by inverters. Gas lanterns light this retail store.

Inside the Amish world, the riddles of technology make sense. Permitting selective use of the telephone and electricity in some settings and not in others is simply a commonsense solution to everyday problems posed by industrialization. Using air and hydraulic pressure to power modern shops while forbidding 110-volt electricity is a reasonable way to encourage economic growth within certain limits.

As we have seen, the Amish are certainly not opposed to technology. They simply use it selectively. They are more likely to accept new technology for productive purposes, “for making a living,” as they would say, than for consumption and communication. They are adamant in not using media technology to consume the values and images of mass society. That line is nonnegotiable. Clearly, they want to build community and preserve social capital, so they employ technology cautiously, ever wary of its potential to tatter the social fabric. And one thing is certain: although the Amish may not enjoy all the conveniences of modern life, they try to control technology and anticipate its long-term consequences.