The Mid-Level Gallery Squeeze

WHAT HAS CHANGED?

Success in many businesses relies a great deal on the impression other people have of how well you’re doing. This is particularly true in the gallery business. Collectors and artists alike will gravitate toward the galleries they believe are moving up in the world and shy away from those viewed as being in trouble. This impact of perceptions explains perhaps why many mid-level dealers who were still struggling by 2014–2015 didn’t want to admit that, even though 2013 annual sales estimates suggested that they were collectively having difficulty. Making it all the harder to admit any difficulty was the fact that top-level galleries and emerging galleries were reportedly doing as well as they had been in 2007, if not better. Even though something seemed to have gone particularly wrong in the middle of the contemporary art market in 2014, having word get out and confirm such problems would only exacerbate them for mid-level galleries. And so many mid-level galleries continued to project an aura of success, even when those closer to their realities knew that was not true.

But what do we mean by a mid-level gallery? Definitions of gallery levels are not easily agreed upon in the industry. Few of the directors of mega-galleries that I’ve talked with would agree they were part of a mega-gallery, perhaps because it has negative corporate connotations. Likewise, quite a number of dealers I would classify as mid-level would argue they are top-level because they honestly view themselves that way, or they believe in the “fake it until you make it” method of reaching your goals.

The following definitions are based on a conversation with Josh Baer (New York publisher and art advisor, as well as former gallery owner) and Elizabeth Dee (New York gallerist and co-founder of the Independent art fairs) that I had in preparation for a panel discussion we participated in at Art Basel in 2013 titled “The Place of Mid-level Galleries in the Age of the Mega-gallery” (watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZstP0Tzl8gY). I have enhanced these definitions a bit since that panel, based on research for this book:

• Mega-gallery: an influential gallery with multiple international locations, deep pockets, a roster of at least forty artists, and a public perception that they’re continuing to expand their enterprise (see Chapter 2).

• Top-level gallery: an internationally influential gallery, possibly with more than one location, a varying numbers of artists on their roster, and yet a public perception that expanding their enterprise is not their top priority.

• Mid-level gallery: [see below].

• Emerging gallery: a gallery that is less than ten years old; initially (at least) having less international influence and a varying number of artists or perceived ambitions; defined predominantly by how new the gallery is, but also generally by having a roster of emerging artists and usually being the owner’s first gallery.

These definitions are still likely to be disputed, but none will stir as much debate as how to define a mid-level gallery. I am holding off on providing my working definition of that level for just a moment to first discuss the range of perceptions that play into this categorization and why it’s often one dealers cringe to have applied to them.

A gallery might be considered mid-level because:

• They are no longer considered an emerging gallery (because they are older than ten years), but are not yet considered top-level, but are viewed as on their way.

• They are older than ten years, have failed to gain enough influence or power to enter into the top level, and are viewed as not likely ever to achieve that.

• They choose to focus on emerging and mid-career artists because of the dealer’s personal curatorial preferences or aversion to competition, and becoming a top-level gallery is not high among their goals.

• They are older than ten years and operate in relative obscurity (meaning they do not participate in any/many art fairs or get much press), but continue to stay in business nonetheless.

Many of the leaders in the contemporary art world will acknowledge the importance of a healthy mid-level gallery system. Their reasoning will run from believing in the artist support network mid-level galleries provide to understanding that as older top-level dealers pass away and their galleries close, a younger generation needs to be ready to step in (and hence pay for the larger booths at the major art fairs or become the members of the senior gallery associations). Others will note, perhaps nostalgically, that they remember how the mid-level phase of running a gallery—when the press often turns its attention to younger galleries and many mid-level dealers are not yet influential enough to amass significant power—can be the toughest in which to stay focused and motivated. There is an even more romantic take on what makes mid-level galleries important, which includes the belief that they are an essential part of the gallery ecosystem, where artists who have passed their “emerging” phase, but not yet entered their “blue chip” phase, can continue to have the opportunity to experiment and develop their work while receiving commercial gallery support. This view informs much of my definition and personal admiration for mid-level galleries.

All romance aside, though, one important distinction between mid-level galleries and top-level galleries that often keeps mid-level galleries from reaching the higher tier is reliable access to the two resources most critical in achieving that goal: money and, perhaps the most important resource money can buy, time. Through the many conversations I have had with dealers in researching this book, I have come to the conclusion that the most common factor that separates mid-level galleries who stay at that level from those who begin to appear as if they’re becoming top-level galleries is how much money and time they can spend to keep their two sets of clients (artists and collectors) happy and still confident in the gallery’s potential to meet their wants and needs going forward.

Another factor that determines which galleries are viewed as mid-level versus top-level is to a large degree beyond any dealer’s control. How consistently they can secure a place in the world’s top art fairs and where they’re located within those fairs is the most public measure of a gallery’s influence. Getting into Art Basel’s sectors designed for new participants, for example, can indeed help a gallery move up the ladder, but unless they eventually gain acceptance into the main section of the fair, the perception will be they are still in their mid-level phase. Some galleries who do continuously get into bigger fairs’ main sections may still be viewed as mid-level because of their placement in the less desirable sections of those fairs’ floor plans. The politics that come into play among the selection committees of those fairs, comprised mostly of the mid-level dealers’ direct competitors, can therefore contribute to the perception that a gallery is still mid-level even when there are not any other discernible differences between their operations and those of the top-level galleries.

Pulling all those factors together then, the working definition of a “mid-level gallery” we will use in this chapter is

A gallery older than ten years; which generally has about eight to twenty-four artists on their roster who mostly fall within the “emerging” to “mid-career” range; which is still usually struggling to secure good placement in the major art fairs; and which often has limited resources to take the steps that could change their position.

The Reality of “the Squeeze”

The notion that there is a “squeeze,” or significant and particular pressure, on the entire sector of mid-level galleries is one that some will dismiss by pointing to the number of them still in business. Why would anyone think there’s anything new about some of them closing and some of them continuing? Isn’t this simply business as usual?

There are some indications that it’s not. First, of course, are those 2013 sales estimates, which have been published widely in the arts press and beyond. As noted above, the perception that mid-level galleries are struggling can become a self-fulfilling issue for dealers at that level. Furthermore, among the New York galleries who were open in 2008 but have since closed (as recorded on the “R.I.P.” section of the blog How’s My Dealing?1), the vast majority of those closing would have qualified as mid-level. Of course, this may be normal in any period, given that top-tier galleries are more stable than those with less influence. But a large number of emerging galleries have opened up since then and plenty of them seem to be doing just fine, which suggests the market overall is not the problem.

It may be helpful here also to consider two factors unique to the mid-level gallery that affect nearly all their business options. The first is related to expectations surrounding the price points for much of the artwork in the mid-level market. Not only do mid-career artists expect to charge more for their artwork than the standard prices for emerging artists’ work, but collectors also expect dealers to work continually to raise the prices for the artists whose work they have purchased. Unlike other businesses where your first step in “moving product” that doesn’t sell quickly is to lower its price, dealers can lose the trust of collectors who learn that someone else got a similar artwork for significantly less than they paid for it, or that artwork they had hoped would steadily appreciate has gone down in value instead.

The second factor transcends the kind of concerns that would apply to most other businesses. As the market evolved, a growing number of dealers who felt happy or at least comfortable in the art world before the recession, and who were by all accounts still doing financially OK in 2013–2014, cited significant changes in what is now required to continue to be a successful dealer as their main reasons for choosing to close their spaces. One might suspect this was merely a “sour grapes” explanation if their rationales were not so consistent and their financial situations were not widely considered to be fairly secure. Themes of how the evolving market was impacting the quality of their relationship with their artists or even the quality of contemporary art in general were common among their explanations for the closures. The following are excerpts from how four emerging-to-mid-level galleries, which most insiders felt were commercially sound, explained their surprising decisions to close around this time.

Galerie VidalCuglietta in Brussels noted in the August 2013 email announcement they sent out that “After many strong exhibitions projects and participations to the best international art fairs, and above all, after building solid relationships with amazing people such as, artists, collectors, galleries, curators, institutions and art lovers . . . we have decided to close the gallery. . . . There are many reasons for this radical and unexpected decision and they all converge to this specific moment where fundamental choices and decisions have to be made to continue to exist as we want to.”

In an interview that Kristen Dodge of New York’s DODGE gallery gave shortly after announcing the closing of her Lower East Side space, she said, “The job of an art dealer is to sell art, and to place that art with meaningful collections whenever possible. The job of an art dealer is to grow the careers of artists, build dialogue around their practice, and solidify their longevity both practically and historically. The job of an art dealer is to bridge the enormous gaps between artists being unknown, artists being known and artists staying known.” 2 Even with this matter-of-fact grasp of the business, and sharing that her gallery was in “good health,” Kristen noted how the changes in what it took to succeed were behind her decision: “I’m not interested in chasing the business to art fairs all year long, handling secondary market works, and growing the gallery to a place where we are forced to make decisions that contradict my reasons for being in it in the first place.” She went one step further to indicate how little room the current system seems to leave for concerns other than money: “However, there came a point when we were looking at The Next Level and from where I was standing, it looked pretty clear to me that the motivation of money (whether out of necessity or ambition) is trumping the integrity of art.”

Among the most successful of the gallerists to share similar sentiments was Nicole Klagsbrun, who after thirty years in the business sent ripples through the New York gallery world with her declaration that “I’m not sick and I’m not broke. I just don’t want the gallery system anymore. The old school way was to be close to the artists and to the studios. Nowadays, it’s run like a corporation. After 30 years, this is not what I aspire to do. It is uninteresting.”3 She went on to note that the current “structure of the system is overwhelming.” Citing an “endless sea” of event-based obligations like fairs and biennials that leave no time to reflect or think about quality, let alone how best to help one’s artists build their careers, she concluded that the result is, “The standard of the art goes down, but there are always buyers and, if you don’t take part, you’re not successful.”

Finally, as of this writing, the latest high-profile mid-level gallery to announce they were closing seemingly had the type of career that would have guaranteed a top-level future, having served on the Art Basel selection committee for many years and co-founded the Art Berlin Contemporary art fair. Described by Artnet as “shocking,” Joanna Kamm’s decision to close the Berlin-based Galerie Kamm echoed those of other dealers who began galleries for reasons that went beyond simply making money. Artnet reported, “Last year, Kamm announced that she would suspend her participation in all art fairs internationally in order to place renewed focus back on the gallery program itself. She subsequently expressed a frustration with being torn between her passion—working with the artists themselves—and the financial pressures of running an international gallery today.”4

Once more, the themes of not enough time and too much focus on money run through their explanations for why the gallery business was no longer right for them. Of course, not every mid-level dealer has chosen to close, and in 2015 there are both a number of reasons to be optimistic about the future and, correspondingly, a renewed determination among many mid-level dealers to find ways to overcome the particular challenges prevalent in their sector of the contemporary art market. Still, the “mid-level gallery squeeze” has loomed large in the art press5, 6, 7, many mid-level galleries have indeed closed, and many mid-level dealers I have talked with have said off the record that things remain challenging. Below we will examine more closely some specific challenges for mid-level galleries, and look at how some dealers are strategizing within or around them. Some of these were indeed challenges for all galleries during this time, but several of them have additional twists for the particular circumstance of mid-level galleries.

STRATEGIES FOR NAVIGATING THESE CHANGES

In addition to listing these challenges in the words dealers would typically use to discuss them, below I attempt to identify the core traditional business issues in play for each (in parentheses), so as to later discuss strategies for them in such terms. The challenges facing mid-level galleries in 2014–2015 included:

• Relatively slower sales and the loss of a key consumer sector

(cash flow)

• Rising rents in gallery districts

(overhead)

• Threat of poaching by bigger galleries and new questions about loyalty

(long-term planning, possibly cash flow)

• Perception of speculation vs. connoisseurship fueling many collectors’ decisions

(sales techniques, programming choices)

• Art fairs vs. gallery spaces where collectors increasingly make purchases

(overhead, sales techniques)

• Internet challenging dealers as source for exclusive information

(promotion techniques, long-term planning)

Relatively Sluggish Sales and the Loss of a Key Consumer Sector (Cash Flow)

As discussed before, the TEFAF Art Market Report survey is controversial because its methodology is not viewed as clearly articulated (and therefore it is presumed to be potentially less rigorous than it should be), and yet its results were reported widely in the arts press and beyond, which helped form the perception that mid-level galleries were seeing relatively sluggish sales compared with the top-level and emerging galleries. As noted above, such a perception itself can present a challenge to mid-level galleries. Specifically, the TEFAF 2014 Art Market Report survey of galleries “indicated that . . . in 2013, the mid market showed lower growth than the lowest and highest ends.” The conventional read on why this was the case in 2013 has been that blue chip contemporary artists were selling very well, presumably because their markets were seen as sound and the wealthy saw art as a stable place to put their money, while at the lowest end there was a great deal of speculative buying, because the price points (generally under $5,000) made it easier to buy with little more than a hope that the work would one day appreciate, but not really worry too much if it didn’t. In the middle, though, where an artist’s prices range from $5,000 to about $70,000 but their place in art history was still relatively questionable, collectors seemed to be taking a more cautious approach.

Here are the TEFAF numbers that helped create this perception of the contemporary art market:

In 2013 . . . the top end of the market, where dealers generated sales of over €10 million, reported an average increase of 11 percent. . . . The share of sales in the lowest end (less than €3,000) was 11 percent higher in share than 2012, while the segment from €3,000 to €50,000 saw the largest fall year-on-year (of -16 percent).8

These statistics are based on a survey of 5,500 dealers from the US, Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. As the report’s notes on data sources revealed, “Response rates varied between countries and sectors, but on aggregate came to approximately 12 percent.” These lower-than-average survey response rates likely reflect that dedication to opacity that art dealers are infamous for. Still, the general percentages seem to accurately reflect both anecdotal evidence and highly public indications of how well any given gallery is doing (such as building out a new location, opening an additional location, hiring more staff, or other things it takes money to do).

The TEFAF numbers also indicated that in 2013 the overall art market had rebounded to nearly its highest peak ever (in 2007) and that contemporary and Modern art were doing exceptionally well in this rebound. The report noted that contemporary mega-, top-level, and emerging galleries reported increases in sales of about 12 percent over 2012. Assuming a rising tide raises all boats, however, it was surprising that artwork priced at the level sold in most mid-level galleries ($5,000 to $70,000) reportedly saw a year-on-year decrease in sales (of 16 percent).

Among the dealers and art fair organizers I’ve spoken with about this, speculation on why the mid-level galleries might still be struggling when galleries in higher or lower levels were not in 2013 frequently came back to the notion of the loss of a mid-level consumer sector. In short, the theory goes that part of what helped expand the mid-level market leading up to its peak in 2007 was that upper-middle to lower-upper class professionals had begun to buy contemporary art in large numbers. Often referred to as “the doctors and lawyers,” these professionals had invested in the stock market, done well there like most other people, purchased their second or third home and their third or fourth car, and were increasingly drawn to the glamorous, event-driven culture of collecting contemporary art. Of course the doctors and lawyers would also purchase plenty of emerging art, like most other collectors, because it was a relatively impulse buy, but they had added an extra boost to the middle market through their sheer numbers. Generally priced out of the blue chip artworks, they were nonetheless quite competitive within the mid-level segment.

Then the recession came in 2008, and purchases of luxury items like art were the first extravagances to go while everyone was trying to assess their financial futures. While many in the financial sectors, technology industries, or real estate began to feel more secure as the recovery took hold, and so began to buy art again, the doctors and lawyers remained uncertain about their finances and didn’t return to collecting. Indeed, professionals in both industries were still struggling in 2014, as these quotes confirm:

Doctors

“At the same time, salaries haven’t kept pace with doctors’ expectations. In 1970, the average inflation-adjusted income of general practitioners was $185,000. In 2010, it was $161,000, despite a near doubling of the number of patients that doctors see a day.”

–Wall Street Journal, August 29, 2014

Lawyers

“Nationally, 11.2 percent of [law school] graduates from the class of 2013 were unemployed and seeking work as of Feb. 15, up from 10.6 percent in 2012. Only 57 percent of graduates were working in long-term, full-time positions where bar admission is required, which is an increase of almost a full percentage point over 2012.”

–American Bar Association, 2014

Again, many mid-level galleries are still in business despite the dual challenges of a key consumer sector not buying during this time and the perceptions created by reports of their relatively sluggish sales. The fact so many remain in business suggests we have not encountered a truly existential threat to the entire middle market, but these dual challenges do contribute to a significant business problem for this sector, which is unreliable cash flow. Specifically, a hard-working dealer can often still make ends meet and keep the doors open despite sluggish sales, but it’s difficult at this level to take advantage of the key opportunities that come along, when they do, if cash flow is a continuous problem. And so the following strategies for the challenge of “relatively sluggish sales and the loss of a key consumer sector” focus predominantly on improving cash flow.

Cash Flow Strategies for Mid-Level Galleries

Consider the following case example as an illustration of how insufficient cash flow can be a particular problem for mid-level galleries struggling to become top-tier galleries or simply to improve their fortunes.

Case Example 1: It’s mid-August.

Your gallery finally got off the waiting list and accepted into Art Basel in Miami Beach (ABMB), which takes place in December. But the participation fee is due immediately. Because you had been on the waiting list several times before, but never before invited to participate, you weren’t really expecting to get into ABMB this time either, and so you hadn’t set aside the considerable amount of money it costs to do the fair.

But this is a “can’t-miss” opportunity to raise the profile of the gallery. If you can be seen to be moving up in the art world, the resulting confidence among your collectors and artists will help you reach that next level.

So you call your gallery angel, a doctor, and ask her to help, by buying something from one of the artists she supports. But she tells you that her practice is suffering at the moment, and so she’s scaling back on her art patronage. She passes on the opportunity to make a purchase and help you out.

You then turn to the collector you sold a major artwork to at some art fair over the summer, but who still hasn’t sent you a check. Their assistant tells you they’re on holiday in Ibiza when you call. Apparently they lost their mobile phone on the beach.

It’s the slowest part of the sales year for your gallery. But your overhead has not gone on holiday.

The ABMB participation fee is due.

Below are several strategies for improving cash flow to be able to take advantage of art fair opportunities as they come along, followed later by strategies for improving cash flow for mid-level galleries in general.

Art Fair Opportunity Cash Flow Strategies

Factoring

Factoring is the practice of selling your accounts receivable (that is, your invoices) to a third party (called a factor) at a discount. Essentially, they give you the money now, minus their commission, and then they follow up with the collector for payment on the art. This can be helpful with collectors who notoriously take a long time to pay, but it also adds a middle man into the dealer-collector relationship.

The Frankfurt-based company, Foundation, specializes in art world factoring. On their website (www.foundationtm.net) they describe themselves as a “supporting partner” particularly for emerging and mid-level galleries. To be eligible to use their services, a gallery must first apply for membership (which includes a US$200 fee) and pay annual membership fees ($150). Each invoice a Foundation member wishes to sell becomes a “ticket,” and upon approval of the ticket, the member receives 100 percent (for small tickets, defined as invoices totaling between $1,500 and $3,499) or 90 percent (for large tickets, defined as invoices totaling between $3,500 and $20,000) of the invoice (minus a “handling fee” of $150 for small tickets and 3.8 percent of the total invoice for large tickets) within forty-eight hours. For large tickets, the balance comes after thirty-five days.

Using a $10,000 sale as an example, then, a mid-level gallery wishing to use this service will need to pay $350 to apply and become a member and then pay 3.8 percent of the sale (or another $380), for a total of $730. Of course the application fee is only paid once, and the membership fee is annual, but in this example, a first-time member would lose 14.6 percent of their commission in order to receive $4,270 within two days. (Remember, most consignment arrangements with contemporary artists are 50 percent of the sale price, and so the gallery would get to keep only $4,270 from this sale after factoring fees [$10,000 – 50 percent to artist = $5,000 - $730 factoring fees = $4,270 to gallery.) That percentage would drop the next time they used the service, of course, presuming they did so before the annual membership fee was due, but unless the artist was willing to split the 3.8 percent handling fee, the gallery’s still losing a significant percent from their half on each such ticket.

The business reality here, of course, must be considered in terms of how much good getting that money quickly could do for the gallery. If another opportunity, such as being accepted into a major art fair, would need to slip through their fingers because a collector takes too long to pay an invoice, factoring could indeed be very valuable. According to a recent report on Foundation in The Art Newspaper, the company has “more enquiries than [they] have been able to process.”9 But in an industry known to be resistant to contracts, factoring still seems to have some convincing to do. In the same article in The Art Newspaper, Heather Hubbs, the director of the New Art Dealers Alliance, said, “I have not heard of anyone using this specific service, nor others like it.” She went on to voice what many in the industry feel, though, saying “any support a small gallery can get is extremely helpful and useful.”

One-Time Backer for an Art Fair Opportunity

Many art galleries have financial backers who invest in the business and either remain silent partners or participate in its operations. The number of gallery backers who are silent is, of course, nearly impossible to gauge, but there are enough cautionary tales about epic—even business-ending—disagreements between dealers and their active or silent backers to make most young gallerists quite skeptical of such arrangements. As noted in my first book, How to Start and Run a Commercial Art Gallery, the key to any such arrangement working well is a clear, solid exit strategy in a signed contract.

Special one-time backing arrangements, however, can resolve immediate cash flow problems and help dealers seize opportunities that they may otherwise have had to pass on. In this context, a backer agrees to front the money needed to participate in a fair, for example, with the terms for repayment carefully spelled out in detail. Assuming sales will be made at the fair, the repayment arrangements might vary from the full gallery commission from each sale going to the backer until the debt is repaid to, perhaps, half the gallery commission from each sale goes to the backer until the debt is repaid, or some other similar agreement.

Of course, getting the backer to agree is the first step. As the case example above indicated, even those inclined to support the gallery may not always be in a position to do so or be willing to share the risk. But one approach here that I have seen work well is to offer the prospective backer a chance to be personally involved in the fair. Certain collectors are curious enough about the operations of the “glamorous” contexts of art fairs that, given an opportunity to be a “dealer for a day,” they will take it. Consulting them on installation designs, involving them in the planning meetings, or having them actually work the booth often provides an intriguing enough “peek behind the curtain” for them to sign on. Many dealers reading this may at this point think, “No way. It’s tough enough already at fairs without having to mix in the complex situation of selling while entertaining a valued collector to support the gallery.” To that, I would suggest most collectors who agree will quickly recognize just how much work it is and not wish to spend too much time being a dealer, so this pitch may still be worth trying.

Booth Collaborations

Currently many art fairs are accepting proposals from two galleries for a joint booth idea, often one presenting an interesting curatorial perspective (perhaps with a rising emerging artist juxtaposed with one more historically recognized, or a thematic installation). Not only do such booths gain media attention, but they obviously cut the costs for both galleries considerably. The advantages here extend to include that with such proposals being popular with many fair’s selection committees (at the moment anyway), such collaboration can improves a gallery’s chances of getting into the fair. It can be a win all the way around.

Talk with the Fair Organizers

I presented some of these ideas at a Talking Galleries symposium in Barcelona in late September 2014, including the case example above. In the audience just happened to be Annette Schönholzer, former director of New Initiatives for Art Basel, and during the talk she noted that such cash flow issues are indeed something many fairs are willing to work around for the galleries they wish to have participate. Telling the fair that invited you from their waiting list that it may take you some time to raise the participation fee is something they have heard before and are often able to be patient about. In other words, rather than pass on the opportunity, explain your situation to the fair and learn what might be possible for payment arrangements.

Overall Cash Flow Strategies for Mid-Level Galleries

During my research, many dealers (of various levels) reported that for six months of the year they do not sell enough art in their physical gallery to even cover their monthly “brick-and-mortar” space expenses. What had seemed to be a more spread-out selling season in years past has now been consolidated, in large part because of the increase in art fairs, auctions, gallery weekends, and other such events. In New York, the better months for selling out of the actual gallery tend to be mid-September through mid-December and then March through June. The other six months, sales drop off, and the galleries exist off the money they made during the better months. This has led to an increased interest in ways to increase cash flow during the slower sales months (overhead continues even if the sales don’t) or in general. Below are some of the strategies mid-level contemporary art galleries in particular are using or at least considering to order to improve their overall cash flow.

Secondary Market Sales

Developing a niche in the secondary art market can be the best long-term cash flow solution for mid-level galleries dedicated to a program that doesn’t always keep them solvent. Doing so requires expertise and can require investment capital, but all the dealers I consider mentors, whose programs are challenging to sell and who yet continue to promote the artists they believe in, report that they can only afford to do so because they are also active in the secondary market.

Magnus Resch, founder of the collector database Larryslist.com and author of the book Management von Kunstgalerien (which is slated to come out in English in 2015) noted in an article in Artnet that: “[For new galleries] to be viable in the long term, it requires the revenue potential of more high-end dealing. Successful galleries cannily use secondary art market income to cross-finance the capital and time invested in building up young artists. And they do this right from the start. Growing with the artists is a nice idea. But if they don’t grow you die. So better diversify.”10

The catch here, of course, is again time and money. Any secondary market niche that is easy to develop will likely involve plenty of competition, and the dealer with the deepest pockets can often secure the best inventory. Even working entirely via consignments to build an overlooked (i.e., obscure) genius’s market basically from scratch (and hence with less competition) can take years of significant work. Then again, recognizing that no matter how hard you work on your primary market sales they are just not likely to happen for six months of the year can free you up to spend that downtime developing the connections and knowledge needed to compete more effectively in a niche secondary market that can eventually turn quite lucrative and support the primary market program.

Complementary Businesses

Knowing that their “brick-and-mortar” expenses are only technically paid for via the sales in those physical spaces six months of the year, some galleries have begun exploring other means of making income through those spaces to help increase cash flow during the slower sales seasons. Not each of these following examples was necessarily started specifically to increase cash flow (that is, they may have been simply part of the gallery’s overarching vision), but they each illustrate a side business that complements the standard primary market gallery model run out of the same space.

My favorite complementary business in a gallery space is the art bookstore in STAMPA gallery in Basel, Switzerland. Not only does STAMPA participate in some of the best art fairs in the world, including Art Basel, but their bookstore is also considered the finest in their city. Definitely part of the gallery’s initial vision, the bookstore specializes in “publications on art, photography, architecture and design as well as videos, artists’ books and editions.” The genius of this complementary business in my opinion is how it helps slow gallery visitors down, which is a growing concern among dealers whose clients increasingly just pop in and out while gallery hopping, which is particularly problematic for programs that benefit from longer viewings or more in-depth discussion about what’s on exhibition.

Another popular gallery complementary business (albeit one that no longer exists) was Passerby, the full-fledged bar at the front of the space where New York dealer Gavin Brown was previously located in the Chelsea district of Manhattan. Not only an easy destination for entertaining collectors and artists, the bar continued operating long past regular gallery hours, but served as a constant promotional tool for their current exhibitions. While not as integrated into the genteel gallery model as a bookstore, perhaps, Passerby did help establish Gavin Brown’s gallery as an alternative context, which lent credibility to some of the less traditional exhibitions he has since became world-famous for presenting.

Interstate Projects is a younger gallery in Brooklyn that executive director Tom Weinrich has supported, in part, through subleasing sections of his overall space out as artist studios. Located in the relatively less expensive district of Bushwick, where many artists already have studios and a strong artist community has developed, Interstate is a good example of perhaps the most direct complementary business a primary market gallery can run: one serving the needs of contemporary artists. I should note that in mid-January 2015, though, Interstate Projects announced that it was switching from a for-profit to a not-for-profit exhibition space.

Another complementary business dealers are increasingly starting (and one we will examine in much more depth in Chapter 8) is a new art fair. Although they are run by large corporations now, many of the world’s top art fairs, including Art Basel and the Armory Show, were initially founded by art dealers who saw a need for the networking and sales opportunities that art fairs can provide. As discussed in Chapters 3 and 9, setting a fair up is a relatively straightforward process, but as a business it can take a few years to turn profitable. My partner Murat Orozobekov and I (initially together with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington of New York’s PPOW gallery), launched the Moving Image art fair in 2011. Organized out of the same space as the gallery, the fair has since evolved to where it helps pay a significant amount of the collective overhead expenses.

Time-and-Place-Specific Solutions

When the recession hit in 2008, and it felt as if someone had cranked closed the faucets of our gallery’s cash flow, we made a conscious decision to turn them back on by launching an editions/multiples collaboration with another gallery, using the hypothesis that while few people were confident enough about their futures at that point to buy much art at typical mid-market prices, artworks in large editions, ranging from $100 to $600 each, should continue to sell well. Of course, any such venture would depend on the quality of the editions, but I can report that our editions sold very well indeed (many selling out entire editions of 100), and the effort resulted in exactly what we needed at that time: it kept money continually coming into the gallery, even if only in smaller amounts.

The time-and-place-specific thinking that led to the editions collaboration was also the realization that we knew plenty of collectors who liked to acquire new works on nearly a monthly basis, but their accountants were warning them against any large purchases. We deduced that works that would fall within the range of their normal monthly expenses wouldn’t raise the accountants’ eyebrows. Also key to our decision was that we didn’t want to undo the hard work we’d done to build the markets of our artists by lowering their prices. Considering the responses we were getting from collectors, it was clear that little of our artists’ usual work was likely to sell for the time being, so we offered them lower-priced work in editions that were obviously a bit outside the artists’ usual practice. This kept the artists’ names out there, gave them and the gallery some (versus no) cash flow, and kept us busy and more optimistic during a time when many other galleries were closing. The satisfaction for me in that episode was analyzing the realities of our collectors’ situations and then matching that with our goals for our artists’ careers and the gallery’s needs.

Rising Rents in Gallery Districts (Overhead)

Every time a gallery moves, whether because they want to or they have to, they see a huge outflow of cash for moving costs, build-out costs, new business cards and stationery, advertising the move, and so on. When a gallery is thriving and wants to move to a bigger space or better location, the psychological impact of shelling out the moving expenses is usually overshadowed by excitement and the potential increase in sales that being seen “moving up” can bring with it. When a gallery is forced to move, because their current location becomes unaffordable, all those expenses can be somewhat emotionally defeating, especially if they are forced into a less-desirable space or neighborhood. Moreover, for mid-level galleries already selling less than their higher- or lower-level colleagues, being forced into an inferior gallery space can dissolve that “successful” aura they are working hard to project.

Rents in the traditional gallery districts of a large number of major cities went through the roof between 2012 and 2014. In London, rising rents in the East End forced a number of galleries to relocate11 or to close.12 San Francisco’s tech boom caused a real estate feeding frenzy that displaced or closed an entire generation of mid-level galleries.7,13 Mid-level dealers I’ve spoken with from Berlin to Barcelona have cited quick-paced gentrification and the resulting sky-high rents as forcing them to seek out new locations. And in New York, Chelsea district galleries saw rents double when many of their leases expired in 2013,14 while even in the more-affordable Lower East Side, rents still increased by as much as 33 percent.15 As The Art Newspaper reported, the mid-level galleries (again, older than ten years, the average length of many New York commercial real estate leases) were hit particularly hard by rising rents:

Rents are rising everywhere. Prices have more than doubled in Chelsea and have risen by around 30 percent to 35 percent in the Lower East Side, dealers say. Middle-level dealers have been hit hardest. Larissa Goldston moved from an upper- to a ground-floor space in Chelsea last year, but is now without a home because the building was torn down to make way for a new residential tower. “Can I afford a gallery space in this landscape and this market? It’s complicated to be in the middle ground,” she says.15

What further distinguished the impact of rising rents for mid-level versus top-level or mega-galleries, in New York at least, was how many older galleries had learned their lesson during the gentrification-influenced migration out of SoHo a decade before and bought their buildings or spaces outright in Chelsea, when it was a grimy warehouse district and buildings were affordable. Now, not only are top-level galleries not being forced to move again, but the increased capital their owned spaces represents further enables them to make choices or offers to clients that many mid-level galleries cannot hope to match.

Strategies for Addressing Rising Rents

Perhaps the most attractive strategy for many mid-level galleries facing undesired moves because of increases in their rent is one of the complementary business ideas noted above. While it may be impossible to incorporate a bookstore, bar, or studio space into their current location, being forced to move does open up the latitude to choose the next space with one of these sideline businesses in mind. Even if another business does not make sense, however, a forced move remains an opportunity to re-imagine what the gallery can be and how it can operate. Below are two strategies (one more concrete than the other) that being forced to relocate often spur dealers to consider, as well as a vision many have talked about for years approaching possible realization in San Francisco.

“Post-Brick-and-Mortar” Gallery Models

While no clearly superior example of a “post-brick-and-mortar” gallery model has emerged that addresses all the disadvantages of not having a permanent exhibition space, there has been a great deal of discussion, particularly among mid-level galleries facing rising overhead and shorter in-house selling seasons, about what that might look like. The thought process here essentially focuses on unfortunate realities like a big decrease in foot traffic in the gallery, sales increasingly happening more via art fairs or online channels, and the six-month period when the physical space is often literally not paying for itself. “If the majority of my sales are at fairs, why am I paying all this overhead for a space fewer and fewer people bother to visit?” is a common refrain.

In Chapter 7, we will examine more closely some of the post-brick-and-mortar models that various dealers are trying out, but among the more cynical responses to the concept of a “post-brick-and-mortar gallery” is that it boils down to former dealers now operating as consultants but still wishing to participate in art fairs. And that may eventually emerge as a viable model. While the major art fairs still require participants to maintain a program in a physical location, the directors of some of the satellite fairs I’ve spoken with indicate they’re softening up their position on that requirement. In short, we may be entering a period in which it is not having a physical space alone that determines whether a dealer can participate in an art fair, and so as a strategy to rising rents, this option may deserve more experimentation. Again, we will explore such models in more depth in Chapter 7.

Relocating to Another Region

The histories of the contemporary gallery districts in major art centers like New York or London have included regular cycles in which dealers were forced to migrate out of a neighborhood that they had paradoxically played a major role in gentrifying. (A great analysis of the factors that force gallery migrations, at least in New York, is found in Ann Fensterstock’s book Art on the Block: Tracking the New York Art World from SoHo to the Bowery, Bushwick and Beyond [Palgrave Macmillan Trade, 2013].) In New York, the current real estate climate has left very little in affordable undeveloped neighborhoods in Manhattan, and even Williamsburg and Bushwick in Brooklyn or the Lower East Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods in Manhattan are becoming or are already too expensive to encourage much more migration beyond the galleries already located there.

So one strategy we are seeing more dealers try recently has been to relocate a mid-level gallery to an entirely new region of the country. Examples of locations that dealers previously located in Chelsea opted for instead include Los Angeles (which is a growing art center but perhaps still not yet a top one, and certainly less expensive), Hudson (in upstate New York), Kansas City, and Miami. Reports from dealers who have relocated to each indicate they’re doing well in their new locations and indeed enjoying the lower expenses. Moreover, there can be some strategic advantages beyond lower overhead to such a move. In more out-of-the-way places, where there is less—if any—competition, dealers can work with more high-profile artists than they can in the highly competitive major art centers. Building your dream program, because the artists you wish to work with have no other representation for miles, can make a big difference in how happy you are as a dealer, as well as which collectors you can attract at the international art fairs. Furthermore, because many major fairs seek geographic diversity in their exhibitors list, being the best gallery from a smaller art region can make it easier to get accepted into the fairs than being just one of several good galleries in a major art center.

The “Minnesota Street Project” Model

From the beginning of the recession in 2008, many generously minded people from other industries advised struggling art dealers to collaborate on a new destination location, so as to lower their collective overhead and benefit from sharing their collective audiences. Even when it was suggested that a patron might lend financial support to such an effort, generally the response from dealers was to note how individualistic galleries are, let alone how competitive. In short, they were not interested. Having watched this discussion for a while now, I’m convinced things simply haven’t gotten bad enough in most art centers for galleries to give this model a try.

Things have gotten bad enough in San Francisco, though. Rising rents have all but wiped out a generation of mid-level galleries in that city. And so it is not surprising perhaps that the first major attempt to implement such a collaborative model is currently underway there. Called “The Minnesota Street Project” (minnesotastreetproject.com), it is the brainchild of collectors Deborah and Andy Rappaport (a respected social entrepreneur and retired tech-industry veteran, respectively). Set to open in early 2016, the Minnesota Street Project’s goal is to provide “affordable spaces and compelling programs to encourage the creation and appreciation of contemporary visual art in the city of San Francisco.” The vision for their 35,000-square-foot warehouse is to house art studios, art galleries, nonprofit arts education entities, and other exhibition spaces, as well as a café and retail spaces. Their longer-term plans include the development of another nearby facility to house additional studios, art storage facilities, and artistic workshop spaces.

Threat of Poaching by Bigger Galleries and New Questions about Loyalty (Long-Term Planning, Possibly Cash Flow)

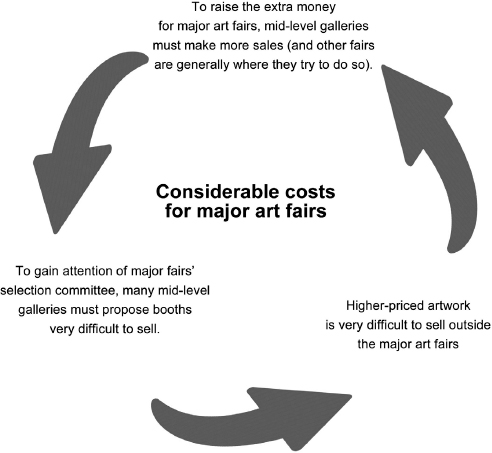

It is often the case that a mid-level gallery has a balance in their program of some artists who sell very well and others for whom they are still developing a market, or even some artists who will likely never sell well, but who are important to the curatorial context the gallery is building. It is understood by dealers that the artists who sell well are crucial to the ability of the mid-level gallery to invest in the efforts that can help them reach the next level: efforts like more expensive art fairs, higher-quality promotional materials, paying production costs for artworks, hiring more staff, etc. When mid-level galleries lose even one of their better-selling artists (and the income for their business that artist would bring), it can have a huge impact on their plans, if not their ability to remain in business altogether. Even when it doesn’t involve a huge financial impact for mid-level galleries, having their top artists poached still involves a potential loss of prestige. The hole it can leave in their often carefully built curatorial context can also present a major new challenge in rebuilding.

Most dealers at any level are quite matter-of-fact about poaching, at least publicly. “It’s a normal part of the business” they will say when asked, even as they otherwise note how personal their relationships with their artists tend to be. In a context of sluggish sales in the middle sector of the market, combined with upper-level galleries very obviously growing their empires by adding new highly bankable artists to their rosters from other galleries’ rosters in order to afford their expansions (see Chapter 2), a number of high-profile artists who moved from their mid-level to a top-level or mega-gallery in New York in 2013–2014 helped generate the perception that poaching had reached a new, rampant level and posed a serious, if not existential, threat to mid-level galleries. Why this threat might be viewed as “existential” relates to the core concept of the Leo Castelli model, and how it is based on the premise that all strategic and many financial choices in marketing an artist’s work feed into the intention of both artist and dealer to grow successful and old together. This is, of course, a somewhat romantic notion, but the degree to which the artist and dealer believe in it also influences the risk a dealer is willing to take on in promoting new, unknown artists. In short, it explains why many dealers will make business decisions that only make sense in a very long-term view.

For example, a dealer who believes his relationship with an artist will last for many years may agree to finance an exhibition that is less likely to sell very much, but highly likely to grab a good deal of press for the artist, thereby increasing her name recognition in ways a more salable exhibition may not have accomplished. These kinds of exhibitions (sometimes referred to as “statement shows”) are often very popular with the press. Make no mistake, though; statement shows often represent a lost opportunity for gallery and artist to earn money during that exhibition. The dealer is willing to postpone the opportunity to see a return on what it costs to present that body of work because the hope is that getting great press will profit both artist and dealer much more down the road when the artist is more well known. However, should this artist take her press and run to a larger gallery before those later opportunities to profit come along, the first dealer is simply out of that money. Multiply that risk across a roster of artists, and the nature of what types of exhibitions galleries are willing to present begins to change unless there’s more reason to expect the working relationship to last.

More than that, if galleries lose the motivation to experiment with ways to get attention for their mid-career artists who have not necessarily benefited from an initial buzz, because doing so only leads the bigger galleries to then come along and poach them, the entire mid-level model becomes unattractive. Dealers previously willing to do the hard work of nurturing artists during their post-emerging/pre-blue-chip phase, because of faith that one day it would all be worth it, no longer have any motivation to play this role in the gallery system if their artists will systemically get poached after they finally build a solid market for them. Enough of this, and the mid-level gallery ceases to exist . . . or so the theory goes.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I should note that I had perhaps helped generate the perception that this new flurry of poaching presented an existential threat to mid-level galleries with a number of posts on my blog (that were subsequently cited more than a few times) in which I was responding to artists moving from mid-level galleries, that I knew depended on sales from their artwork, to bigger galleries. I happened to know the impact of those moves on those mid-level dealers was significant, but the semi-apocalyptic narrative I derived from these anecdotes and conversations with some of those dealers eventually began to tug at the back of my consciousness. How rampant, really, was poaching among galleries between 2008 and 2014? More importantly, did it really represent the existential threat to mid-level galleries that it seemed to?

To find out, I researched the movement of artists in and out of the rosters of thirty-two high-profile New York galleries. By “high-profile” I mean galleries who would normally participate in one of the major fairs that take place in New York or have high-profile artists currently worth poaching (or worth it to the press to write about a poaching). There are an estimated 600 galleries in New York, but the kind of poaching that has been sending shockwaves through the entire gallery system has typically happened more among these high-profile galleries (that many galleries aspire to become) than the lower-profile ones. Taking as a baseline number then, and in lieu of any more concrete metric, that roughly sixty New York galleries take part in any one of the major international fairs held in New York City, the thirty-two galleries included in the research represent a sample size of 50 percent of the total population in question. (Clarification on methodology: My reasoning for focusing on this subset of “high-profile” galleries is that even if a mid-level gallery is not currently part of this subset, a new culture of rampant poaching from larger galleries would still pose the same threat to their eventually reaching the next level.)

Of the thirty-two galleries I researched fourteen were mid-level galleries, fourteen were top-level galleries, and four were mega-galleries. For each gallery I created a spreadsheet comparing their 2014 rosters (as presented on their current websites) with their 2008 rosters (as presented on the archived 2008 version of their websites viewable in the “Way Back Machine” [https://archive.org/web/]). I then researched each artist who had either left or joined each roster, thoroughly reviewing their CVs on their personal artist websites and all their other galleries’ websites (including those outside New York), researching any press about their movement, and reading the archived news sections on the websites for both New York galleries for articles on newly represented artists or any promotion of the artists assumed to still be part of the roster when published. It took quite a few months. In the end, the data suggested a number of very interesting trends, not all of them reflecting well on the mid-level dealers I had sought to champion. I chose New York obviously because of personal access to more insider information here. Much of what these galleries’ websites did not reveal I have been able to learn through direct conversations or through the grapevine.

Here it behooves me to clarify my findings with particular care. Even where I have firsthand knowledge from dealers or artists that artist X was indeed poached by gallery Y, I recognize that humans have all manner of reasons for exaggerating or leaving key information out of their accounts of such circumstances. Therefore, I will note that the following information only assuredly represents the movements of artists from one gallery to another, and even where it would appear obvious that the artist strategically moved from a smaller gallery to a larger one, I am not definitely asserting that “poaching,” per se, was involved. Mind you, I go to this length in making this disclaimer because, despite how many dealers will insist that poaching is just another normal part of the business, few of them seem comfortable discussing it in the same way they would discuss shipping costs or preferred insurance companies, let alone admit they had poached an artist from a gallery they knew depended on his or her sales. Moreover, my goal here is not to point fingers, but rather to identify patterns and eventually to discuss strategies for handling poaching.

Therefore, no names of artists or galleries will be used, only an anonymous ID indicating the level I assigned to each gallery (using all the criteria outlined in the gallery level definitions above) and an arbitrary number. Before presenting the data that would indicate poaching trends, however, let’s first look at movement of artists in and out of these galleries’ rosters more generally. In the tables below, MG = mega-gallery; T = top-level gallery; and M = mid-level gallery.

Increase in size of roster and retention of artists among 32 high-profile New York mid-level, top-level, and mega-galleries from 2008 to 2014

Breaking things down by gallery level here, between 2008 and 2014 the increase in the number of artists on the gallery roster among the sampled mid-level galleries averaged 18 percent; for top-level galleries, the increase averaged 10 percent; and for mega-galleries it averaged 39 percent, which is consistent with the distinction made above between how top-level versus mega-galleries prioritize the rapid expansion of their empires. Breaking down by level the percentage of retention (that is, the artists each gallery had represented in 2008 that they still represented six years later), the mid-level galleries averaged a 54 percent retention rate; the top-level galleries averaged 69 percent; and mega-galleries averaged 68 percent. Again, none of these particular results can be interpreted to reflect anything significant about poaching. There can be any number of reasons for artists leaving a gallery, including death, a career change, personality clashes, and so on. Rather, these averages represent merely the overall context in which artists switched or left galleries during this time, whether via poaching or not.

However, when mapping which artists left one gallery to work with another, especially when it would seem from their CVs and press that the gallery being left would feel a significant impact from that decision (mostly financial, but also perhaps prestige-related), a general impression of how many such movements would strike one of the dealers involved as “poaching” or close enough begins to emerge. Here again, though, I feel it is important to choose my words with care. The table below should not be interpreted as evidence of poaching, but rather my interpretation of the months of research and analysis into when the move of each artist was likely to have had a significant negative impact (or not) on the gallery being left. Again, though, clearly there is only so much I can tell even from the materials I reviewed or the conversations I have had.

Percent of change in gallery rosters likely having a negative (or no negative) impact on 32 high-profile New York mid-level, top-level, and mega-galleries from 2008 to 2014

The most surprising result here for me was how the totals suggested that, on average, only 33 percent of all moves by artists between these galleries likely had a negative impact on one or the other involved gallery, as opposed to the remaining 67 percent of moves that would appear to have only had a negative impact on the involved artists (we’ll examine that notion in more detail below). Then again, 33 percent is still negative enough to warrant discussing strategies for how to minimize the impact of such moves when they happen, which we will do below.

Breaking down these numbers by gallery level, we see that the average percent of change in each gallery’s roster that was likely to have a negative impact on that gallery was 13 percent for mid-level galleries; 16 percent for top-level galleries; and 6 percent for mega-galleries. In this context alone, mid-level galleries would seem to have less reason to complain than top-level galleries about losing artists. Of course, these numbers tell us nothing about the percentage of total sales the artists leaving the respective rosters brought in for each gallery. As noted above, many mid-level galleries have some artists who sell well and often many others who they are still just building a market for, meaning they can less afford to lose their best-selling artists than arguably can a top-level gallery, which generally has many more artists selling well. Finally, as expected, when a mega-gallery signs any artist, the likelihood of them moving would appear to drop considerably.

Let’s return to the negative impact these findings suggest were felt only by artists. To help understand the landscape here, I looked at the data in two contexts. First was a comparison of the percentage of artists who seemed to have just been dropped with the percentage of artists from each gallery who were likely poached or somehow otherwise ended up with another New York gallery, to get a sense of whether galleries were dropping more or fewer artists than they were having poached. Second was to calculate what percentage of all the artists on each gallery’s 2008 roster were presumably just dropped by that gallery, to determine across levels which gallery sector was dropping artists the most or least. I will expand on what I assume each context means below, but first the numbers:

Percent of artists presumed just dropped vs. percent of artists with another gallery by 2014 (including those presumed to have been poached)

Looking at these numbers by gallery level, the average percentage of artists represented by mid-level galleries in 2008 who were dropped and still had no other New York gallery by 2014 was 66 percent. The average for top-level galleries was 56 percent, and for mega-galleries it was 62 percent. For each level, the percentage is more than 50, suggesting that artists who are dropped by New York galleries have a tough time finding new ones. Again, there can be any number of reasons galleries drop an artist, but I feel safe in assuming the number one reason among younger and mid-level galleries is that the gallery had been unable to find enough buyers for their artwork.

As these results became apparent during my research, I began to wonder whether the loyalty it takes to maintain the Leo Castelli model, which I had assumed was waning predominantly among a new generation of ambitious artists, had not instead first or correspondingly dissipated among a new generation of ambitious art dealers. To help shine some light on that, I looked at the findings solely from the point of view of how many artists were dropped from each gallery’s 2008 roster. In other words, rather than retention, what was the dismissal rate among galleries in each level, and what role might that also play in the evolution of the contemporary art market? The phrasing in the table below might sound a bit harsher than each individual decision these galleries made would warrant, but remember one central idea behind the Castelli model had been that galleries would support their represented artists, though thick and thin, for the long haul.

Percentage of artists on each gallery’s 2008 roster who appear to have been just dropped

Now here I must admit that I have been as guilty, if not more so, of dropping artists as any other New York mid-level dealer I know. At the time, each such decision seemed essential to meet our goals for the remaining artists on the gallery roster, but in hindsight it is clear that I had simply rushed into representation with some of them, which is a topic we will discuss more below. Ultimately, though, seeing the numbers above suggested to me that if the Leo Castelli model has indeed given way to recent developments in the overall marketplace, some of the blame can be laid squarely at the feet of dealers themselves.

Breaking the numbers down by level, the percentage of artists on 2008 rosters just dropped by mid-level galleries averaged 25 percent; for top-level galleries it averaged 14 percent; and for mega-galleries a mere 4 percent. There are other considerations here, including that mid-level galleries are often still actively taking on emerging artists with little to no existing market, whereas top-level and mega-galleries tend to only sign up highly bankable artists. But the “throw them all against the wall and see which ones stick” method of representing artists is not consistent with the romantic notion of “we are in this together, for the long run” that many dealers will insist defines their gallery.

It should also be noted here that of the high-profile poachings in 2013–2014 that originally led me to view this as a serious threat to the mid-level gallery ecosystem, each dealer who had been left had done a truly phenomenal job in promoting those emerging artists. They were the first dealers in New York to exhibit them, often with early-on head-scratching among the culturati and less-than-stellar sales, and yet they stuck to their guns and kept promoting these artists into the limelight, until larger galleries took notice and eventually wooed them away. In other words, they did what we applaud the best dealers for doing: discovering important artists and convincing the world to take notice.

I know these decisions are often difficult for artists, and the top-level and mega-galleries often have the resources to make it appear a no-brainer that such moves are wise, but whether it began with the new generation of dealers or the new generation of artists, the concept of loyalty at the heart of the Leo Castelli model seemed increasingly quaint and antiquated by 2014. Here again, I began to suspect my objectivity was being influenced by my admiration for the galleries and dealers who had been left. So I conducted an online survey, promoted via Facebook, Twitter, and my blog, which resulted in 1,380 self-declared artists responding from over 31 countries across North and South America, Europe, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and the Middle East.

One of the questions in the survey sought to gauge whether “loyalty” to their galleries still mattered to artists. Each of the artists responding was first separated by whether they had current gallery representation or not. Of the respondents, 60 percent (or 835) of the artists had no current gallery representation, while 40 percent (or 545) of them had representation with at least one gallery. The loyalty question was framed slightly differently for the two groups. For artists with gallery representation, the question was “In general, how important is the concept of ‘loyalty to the gallery’ to you in your relationship/s with your gallery/galleries?” Their responses were

| RESPONSE | Number | Percentage |

| Extremely important | 86 | 25.1% |

| Very important | 150 | 43.9% |

| Moderately important | 83 | 24.3% |

| Only somewhat important | 15 | 4.4% |

| Not at all important | 8 | 2.3% |

For artists without gallery representation, the question was phrased “In general, how important is the concept of ‘loyalty to the gallery’ to you in a relationship with a gallery?” Their responses were

| RESPONSE | Number | Percentage |

| Extremely important | 79 | 17.3% |

| Very important | 202 | 44.2% |

| Moderately important | 107 | 23.4% |

| Only somewhat important | 43 | 9.4% |

| Not at all important | 26 | 5.7% |

Of the artists with current representation, then, 93.3 percent of them considered “loyalty to the gallery” moderately to extremely important, whereas among artists without representation only 84.9 percent did, which is understandable perhaps; why would artists who don’t have galleries feel any loyalty to them in general? Overall, though, these responses suggest that artists still consider loyalty an important part of the artist-gallery relationship. How many of these same artists had perhaps been “disloyal” by permitting themselves to be poached by another gallery is not something I asked, but the disparity in the percentages of artists who viewed loyalty as “important” versus the percentage of galleries that had “just dropped artists” between 2008 and 2014 in New York suggests again that the Leo Castelli model had been abandoned more by dealers than by artists, and in particular by mid-level dealers scrambling to survive the Great Recession.

On the other hand, the impact on mid-level galleries when their best-selling artists are poached can be much more significant than it is on larger galleries. Mid-level dealers I’ve spoken with have shared that even one best-selling artist deciding to leave their roster had greatly changed how they viewed their relationships with all their artists. Moreover, even the threat of poaching can make mid-level dealers spend resources on defensive measures that they might have otherwise spent growing the gallery. Below are strategies for addressing poaching from both the notion of what role loyalty plays here and how to minimize the impact when poaching does occur.

Strategies for Approaching Loyalty and Poaching Issues

Loyalty Strategies: Encourage More Loyalty Among Young Gallerists

Because of the amount of money in it at the moment and the total number of dealers seriously seeking a chunk of that money, the contemporary art market has become hyper-competitive at the same time that all of life, and the way information moves around in it, has quickened to historic speeds. I view this new competitive and complex landscape as contributing to how many younger and mid-level dealers have repeatedly lost patience with their curatorial visions. The highly visible success of a few galleries at those levels, combined perhaps with the ego it requires to open a commercial art gallery in the first place, has made it difficult for less-successful dealers not to conclude it is their program’s fault that they are not also successful in this climate. This has led to what appears to be an accelerated cycle of trying on new artists and then letting them go if sales do not follow quickly enough.

Letting artists go was certainly more the case for Leo Castelli than his myth now would suggest, but as the survey above indicates, artists still value loyalty, seemingly more than many dealers do. Therefore, perhaps one defense against poaching is for dealers to more consistently demonstrate that the loyalty they wish to enjoy is a two-way street. If an artist sees their dealer just dropping other artists from the gallery roster, it will occur to them that they could be next. This contributes to the increased resolution among artists that if a good opportunity to jump ship comes along, they should take it. If the current model is to survive, dealers who have been in the business longer, and who frequently mentor younger dealers, might need to make a bigger point of encouraging more loyalty to the artists younger dealers sign up, explaining that the long-term benefits of such relationships, for both the gallery and the contemporary art scene at large, depend upon this kind of commitment.

Loyalty Strategies: Reconsider How “Representation” Is Discussed and Offered

My point in the paragraph above is not that a gallery should continue to represent every artist it ever signs up even if the relationship is obviously not working out, but rather that perhaps the rush to offer artists “representation” needs to be reconsidered. Younger galleries are often quick to offer artists representation as a means of protecting their initial investments in promoting their work. What if I take their work to a fair, we sell out the booth, and other, bigger galleries come along and snap them up, because I haven’t offered them official representation? Another concern is that by not offering the security of representation, the artist will view the gallery’s commitment as halfhearted and feel it’s wise to explore other opportunities. Both those concerns rise from the unrealistic expectation that when the partnership is “right,” the artist and dealer will know it because they essentially “fall in love” at first sight and that any less fantastic start is a warning sign the partnership is not “the one.” This rather romantic notion comes both from the Leo Castelli model myth and the desire on many artists’ part to find a dealer who is completely devoted to them and their art.

What seems to be needed as a measure against dealers signing up so many artists they will simply drop later is perhaps a middle phase, where it is clearly stated how much the gallery is going to invest in the artist and it is clear the gallery expects to make that money back (by making money for both of them), but that official representation should only be entered into when both parties are confident the partnership is sound. Yes, the risk remains that an artist will agree to representation with a different gallery during this “trial” period, but with a clear dialogue about how much the gallery is behind or ahead in a return on its investment, the conversation about any such defections can be less destructive for the gallery being left.

This would require, of course, more detailed bookkeeping about expenditures in promoting each artist than many galleries currently do. What percentage of the gallery website is rightly considered an investment cost in promoting that artist, for example? If an artist decides to sign up with a different gallery, knowing the total amount invested in the artist can facilitate a more productive conversation on what can be done to help the initial gallery recoup its investment (more on that below). Yes, this approach would sap some of the romance from the artist-dealer relationship, but it is having romantic notions like those smack headlong into reality that ultimately makes artists more skeptical of the gallery system, and ultimately creates even more problems around trust and loyalty.

Loyalty Strategies: Forget Loyalty

It should also be considered, as the art market grows increasingly complex, that perhaps things have changed forever, and the more romantic elements of the Leo Castelli model are no longer viable. I discussed the loyalty issue during my presentation at the Talking Galleries symposium in Barcelona in October 2014. During the Q&A, a collector in the audience said, “I have been collecting for 30 years. I think that very bluntly, we speak of the ‘art market’ . . . it’s a market of art, and you should not forget that if it’s a market there are a number of rules which are common to all types of markets . . . and I don’t think that ‘loyalty’ exists in any type of market.”

I would counter now (at the time, the presentation was winding down and I wanted to be sure the collector had time to express his opinions, so I didn’t disagree) that the question of loyalty is between an artist and his or her agent, the dealer, and that many of the issues they work out in that relationship transcend the selling of the art on the market. Often they are curatorial in nature, or even personal. And so it is not entirely within the realm of the art market, per se, that such questions emerge. But I do acknowledge that perhaps ideas around loyalty need to evolve as the market becomes more complex and competitive. I titled this subheading “Forget Loyalty,” but knowing how much value artists place on it, I’m not sure entirely forgetting it makes dealers effective agents for artists.

Still, the future of the artist-dealer relationship would seem to be one that includes more formalized agreements (that is, more contracts), which if used correctly will enhance, but not entirely replace, the way loyalty makes the partnership more effective. Part III of this book delves more deeply into how contracts are being reconceived to address evolutions in the art market and in particular the artist-dealer relationship.

Poaching Strategies: Discuss This Upfront