Chapter 2

MARC BRUNEL

The Revolution Begins

What I find most amazing about Marc Isambard Brunel is that Hollywood has never seen fit to produce a blockbuster movie about him. His story of world-shaping success has all the ingredients that you might expect from a late-18th century James Bond or Indiana Jones; a larger-than-life character who so often would throw caution to the wind, in the pursuit of a greater goal, regardless of the risks – with a classic fairytale romance thrown in.

Rejecting the life of a priest at an early age and cheating the guillotine, in Scarlet Pimpernel fashion, during the French Revolution – as would his future bride – Marc Brunel escaped to the United States, where he made his name, before losing his fortune in England and winning it back again.

Not only that, but – most importantly – there would be a futuristic tunnel involved along the way – an essential ingredient in most Bond films. This one, however, would not be the fictional big-screen den of some sinister mastermind who wanted to take control of the world, but one which would genuinely change it in more ways than the young Marc could ever have imagined.

Furthermore, he would have a son who would not only follow in his engineering footsteps, but who, nearly two centuries after his birth, would take second place behind Sir Winston Churchill in a nationwide poll to find the greatest Briton of all time, even beating Shakespeare – not bad for someone who was half French.

Marc Brunel was born on 25 April 1769 in the hamlet of Hacqueville, near Rouen in France, the son of a wealthy farmer, Jean Charles Brunel, and his second wife, Marie Victoria Lefevre.

As soon as he could read and write, the young Marc displayed a talent for drawing, mathematics and mechanics.

His father, however, was having none of Marc’s aspirations to become an engineer and join the new breed of pioneers spawned by the Industrial Revolution, on the other side of the English Channel.

Samuel Drummond’s portrait of Marc Brunel in later life, showing the Thames Tunnel, his greatest achievement. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

The fall of the Bastille on 14 July 1789. The ensuing Reign of Terror not only brought royalist Marc Brunel and his future wife together, but led to him fleeing France and making his fortune as an engineer in New York.

The block mills in Portsmouth’s dockyard where Marc Brunel set up shop on behalf of the Royal Navy, following his arrival from the USA. PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

The plaque, which marks the spot where Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in Portsea. PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

Jean Charles insisted that his son had a career in the church, and so at the age of 11, he was sent to a seminary in Rouen.

There, the Superior saw that Marc’s talents in drawing and woodwork would be better engaged elsewhere, especially as he had no religious leaning. So, it was arranged for him to stay with an elder cousin, Madam Carpentier, whose husband, a retired ship’s captain, had become the American consul in Rouen.

While living with the Carpentiers, Marc attended the Royal College in Rouen, and excelled at mathematics, geometry, mechanics and drawing.

His scholarly success led him to a place as a cadet on the naval frigate Marechal de Castries and a six-year career at sea.

In January 1792, Marc returned home to find his native country embroiled in the worst excesses of the French Revolution. A Norman, and a staunch royalist sympathiser, he was at odds with the aims of the murderous Jacobins.

When, in January 1793, he made scathing remarks in a speech about the brutal Robespierre, during a visit to the Café de l’Echelle in Paris, he was lucky to escape a howling, revolutionary mob by the skin of his teeth, hiding in an inn for the night.

In Rouen, he found that the Carpentiers had a new guest, 17-year-old Sophia Kingdom.

She was the youngest of 16 children of Portsmouth naval-contractor, William Kingdom, who had died some years before. Her family had decided to send her to France with a friend, Monsieur de Longuemarre, and his English wife.

Feeling the heat because of his sympathies with the Ancien Régime in France, and with Rouen in Jacobin hands, Marc fled the country for the USA, alone, but with the elaborate help of friends, amid justifiable fears for his safety.

He obtained a passport, after falsely claiming he was buying grain for the Navy, sailed away on the aptly named Liberty, and then established himself as a surveyor, architect and civil engineer in New York.

There, Marc built the old Bowery Theatre, in its day, the largest theatre in North America. He also built many other buildings, including an arsenal and a cannon foundry, as well as improving the defences between Staten and Long Island, and surveying a canal between Lake Champlain and the Hudson River at Albany.

Bust of Mark Brunel in the Brunel Engine House museum, above Thames Tunnel at Rotherhithe. ROBIN JONES

He eventually took US citizenship and became chief engineer to the city of New York.

One of his designs won the competition for a new US capitol building to be built in Washington DC, but it was found too costly to implement and another plan was chosen instead.

While Marc prospered on the far side of the pond, Sophia remained in grave peril for her life.

Following the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, Britain declared war on France, and all British nationals were imprisoned. Sophia found herself in a convent at Gravelines, near Calais, which had been turned into a makeshift prison – complete with a guillotine. This, despite representations from the Carpentiers and Republican families, whose children she had taught English.

Sophia was not released until July 1794, when Robespierre was overthrown. The following year, she returned to her family’s London home.

In February 1799, Marc decided to leave America and start again in England – perhaps driven by an all-consuming desire to renew his acquaintance with Sophia, whom he had never forgotten.

They were reunited in spring that year, and were married at the parish church of St Andrew in Holborn, on 1 November 1799, setting up their first home in Bedford Street, Bloomsbury.

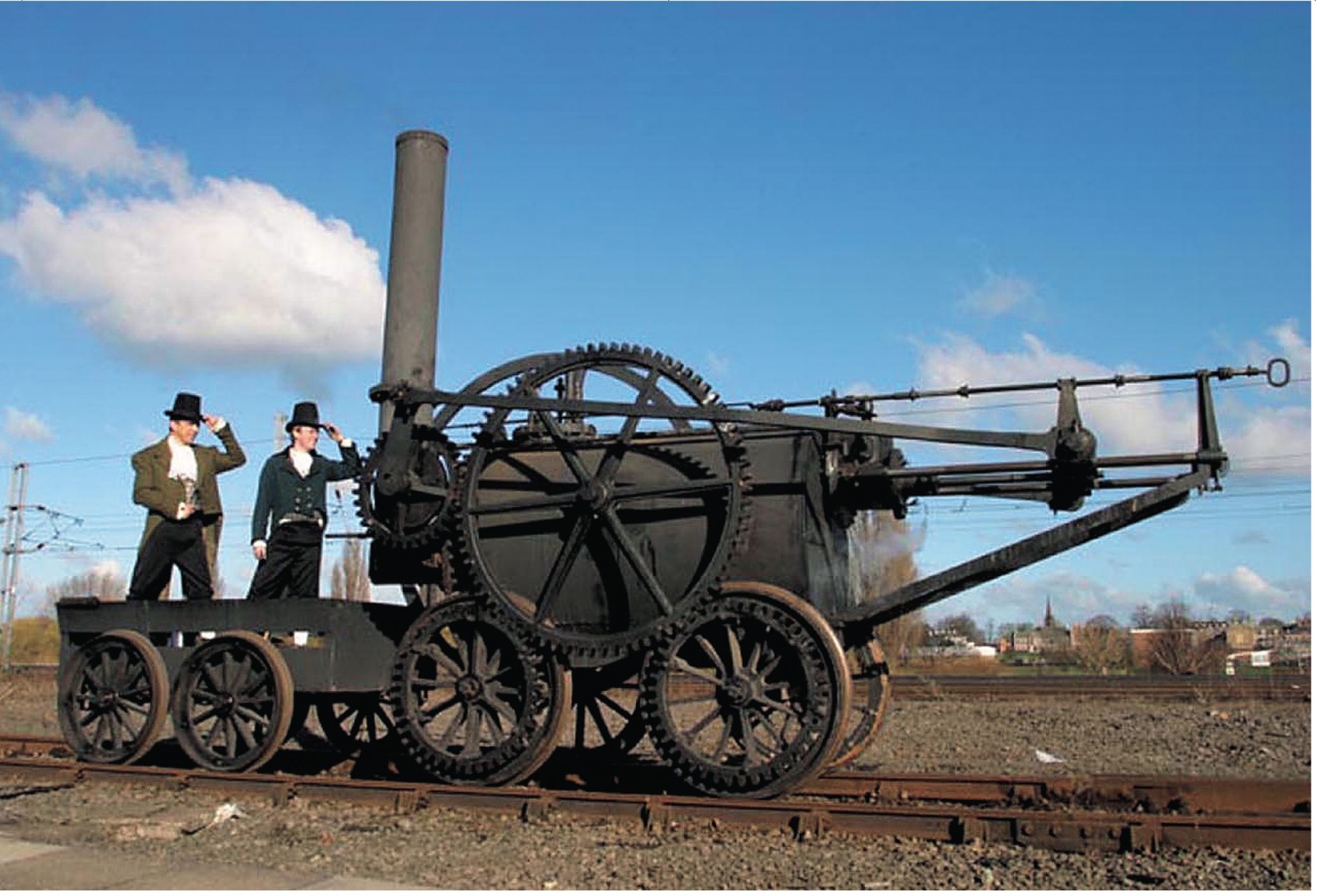

The modern-day replica of Richard Trevithick’s 1804 steam railway locomotive, a world first, in action at the National Railway Museum’s Railfest 2004 event in York, which marked the bicentenary of its first run. Marc Brunel and his son Isambard spent 10 years in vain trying to develop a gas-powered alternative. In the end Isambard would go for steam in a big way, but would still look for alternatives. NRM

Marc had certainly not left his entrepreneurial spirit behind him in New York, in the first few weeks of his arrival in Britain; he had filed a patent for a ‘duplicating, writing and drawing machine’.

However, his big break came when the Government awarded him a £17,000 contract, after accepting his plans for mechanising the manufacture of pulley blocks for ships, which until then had been made by hand.

By 1808, a total of 43 machines of his design were installed in the naval dockyard at Portsmouth, where they became one of the earliest examples of all-mechanised production in the world.

With the machines, 10 men could do the job previously done by 100, and furthermore, Marc’s blocks were superior in quality and consistency to the handmade predecessors.

The Brunels moved with their new daughter, Sophia, to a small terraced house in Portsea, near Portsmouth, from where Marc supervised the six-year project to build the block-making factory.

It was at this house in the early hours of 9 April 1806 that Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born.

The bust of Isambard Kingdom Brunel in Rotherhithe’s excellent museum in the Brunel Engine House. ROBIN JONES

Marc went on to design great, steam-powered machines for sawing and bending timber, some of which were also taken up by the Navy. He also worked on devices for stocking knitting and printing.

Horrified at the condition of the feet of soldiers returning from the Corunna campaign in 1809, Marc invented a series of machines to mass-produce boots and shoes, filing a patent the following year. His idea proved so successful that the Government asked him to expand production.

At Chatham’s dockyard, Marc installed one of his sawmills, served by a rope-hauled railway with rails that were 7ft apart – much, much more of that later.

His success in the woodcutting field led to him joining forces in 1807, with a Mr Farthing, to set up a sawmill business in Battersea, and so Marc moved back to London with his family to oversee it.

While the block-making operation was a success, the Navy proved to be slow at paying, and the Brunels needed a more regular income. Like everything that had gone before it, the sawmill was a success – Marc supplied the technology, Farthing the finance and business acumen.

All went well until Farthing retired in 1813, and then, without his hand on the tiller, the firm’s finances fell into neglect.

The next year, the sawmills were all but destroyed in a fire, and Marc, when he finally looked at the bank balance, found the firm’s finances to be far worse than he had thought.

Just to add to his financial woes, his army boot factory was dealt a major blow by Wellington’s victory at Waterloo in 1815.

The Government decided to reduce the size of the Army, and Marc was left with a consignment of unwanted boots. He had to sell them off cheap to fund the rebuilding of the sawmills.

In the meantime, Marc, who had been elected to the Royal Society in 1814, had spent much time devising a series of new inventions, many of which were far less successful than his block-making equipment and saws.

In 1812, he experimented with steam navigation on the Thames, to no avail. He devised a series of compressed air engines, which turned out to be impracticable, designed a knitting machine, which nobody would buy, and entered into fruitless talks with the Russian Tsar, Alexander I, for a suspension bridge across the Neva River in St Petersburg.

Marc then came up with a handheld copying press, a device, which could make decorative packaging from tin foil and also began work on a rotary press for the Times newspaper.

Disaster hit in 1820, when, after years of continual, habitual neglect of the financial, rather than, technological side of his ailing business empire, his bankers, Sykes & Co, were now insolvent, and nobody would honour his cheques.

Marc and Sophia could no longer pay their debts and on 14 May 1821, were hauled off to the King’s Bench debtors’ prison, where they spent three months – until influential friends, led by the Duke of Wellington, managed to persuade the Government to stump up £5000, lest the inventor’s services be lost to Russia, where the Tsar had shown renewed interest in his Neva River scheme.

Able to pay off his crippling debts at last, Marc resumed his career in a far more humble manner, becoming a consulting engineer in an office at 29 Poultry, in the City of London.

Young Isambard Kingdom Brunel had, in the meantime, been groomed by his father to take over the business.

Marc taught his son drawing and geometry, before sending him to Dr Morell’s boarding school in Hove. While at the school, Isambard carried out a survey of the town and made many drawings of the houses there.

At the age of 14, he was sent to France to finish his schooling at the College of Caen, in Normandy, and progressed from there, to the Lycée Henri-Quatre in Paris. He also studied at the Institution de M Massin.

His father had also arranged for him to have an apprenticeship under Louis Breguet, the world-famous maker of clocks, chronometers and other scientific instruments.

While his father underwent what the family described as his ‘misfortune’, Isambard had been abroad, not returning to England until August 1822, at the age of 16.

He immediately took up work in his father’s office, working alongside him on designs for a cannon-boring mill for the Netherlands government, the rotary printing press – amongst much else, including two suspension bridges for the French Government for the Île de Bourbon (Reunion) off Mauritius.

The father-and-son team worked on more mechanical engineering designs, and came up with the first double-acting marine engine, which set on course a chain of events, which would lead Isambard to worldwide fame and glory.

Two years before Isambard had been born, in 1804, a Cornish mining engineer named Richard Trevithick had sown the seeds of a transport revolution which would change the face of, and shrink, the globe: the first railway locomotive.

While Ironbridge is widely regarded today as the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, necessity was very much the mother of invention in the wilds of Cornwall, where the landscape so beloved by holidaymakers today, resembled the Black Country or South Wales coalfields in their heyday, being littered with the engine houses, processing mills and slag heaps of various tin, copper, lead and arsenic mines.

The biggest problem for mining was keeping the tunnels free of water, and some of those in Cornwall stretched out beneath the sea. It was the stationary steam engine, which provided a satisfactory means of pumping out water so that the mines could be worked safely.

All well and good, but there was the difficulty in transporting large, steam-engine components from manufacturers like Boulton & Watt of Birmingham, to the Duchy for assembly – Cornwall was never connected to the canal network, which had made the Industrial Revolution ‘happen’ and its mining areas lay in hilly terrain that were mainly accessed only by sea.

But, what if a machine could move by itself to the site where it was to work, instead of being dragged there by horses?

Furthermore, what if it could pull other machines, and maybe even carry people?

Trevithick, who was born on 13 April 1771, did not invent the first machine that could move itself using the power of steam.

That honour goes to Austro-Hungarian army officer Nicholas Joseph Cugnot, who wanted to devise a more efficient means of moving heavy artillery than horses, resulting in the world’s first steam tractor, which appeared in 1769, with a refined prototype displayed in Paris the following year.

Cugnot’s invention was a clumsy and overweight device, with appalling steering, or lack of it, and which could operate for only 20 minutes before it needed to cool down and have fresh water added – not exactly an asset in battle. His work came to an abrupt end when his weighty machine overturned in a busy street.

Meanwhile in Britain, Scotsman William Murdoch had been experimenting with steam traction while working for Boulton & Watt as its Cornish agent, and in 1784, his first working model hauled a wagon around a room, inside his Redruth home.

Murdoch then gave an infamous outdoor trial to a 19in-long, three-wheeled steam carriage one night along the narrow lane leading to the town’s church. The machine ran off without him, at 8mph, and terrified the rector, who believed that the devil was about to attack him.

Undeterred, Murdoch built an improved model and apparently a further two carriages as well – and they were seen not only by the townsfolk of Redruth but, also by the young Richard Trevithick.

However, Murdoch’s work ceased towards the end of the 1790s, and he is better remembered as the man who invented gaslight, using it to light his Redruth home.

Trevithick, however, was working on increasing steam pressure, so that he could make smaller engines. He quickly realised that if a much-smaller engine could power a machine or pump, then it could also be capable of being adapted to drive itself.

Forming a partnership with Andrew Vivian, he launched his own steam carriage on Christmas Eve 1801, when it successfully climbed Camborne Hill under its own power.

Several onlookers ecstatically jumped aboard and rode on it – making it the world’s first motorcar.

There was jubilation all round and those involved in the escapade celebrated at the inn at the top – leaving the locomotive to burn out.

Two subsequent experiments with steam carriages in London proved unsuccessful, purely because of the unsurfaced roads of the day, so Trevithick sought a medium, which could support their great weight – the railway.

In 1802, he began work on building a railway locomotive for use at Coalbrookdale ironworks in Shropshire, near the site of the world’s first iron bridge, although it was not believed to have run in public. He was then asked to install a high-pressure locomotive to run from Penydarren ironworks near Merthyr Tydfil, along the horse-drawn tram road that linked the works to the Glamorganshire Canal at Abercynon wharf, and jumped at the opportunity.

On February 21 1804, Trevithick’s engine hauled a rake of loaded wagons, plus 70 men, along the full length of the tramway, immediately earning him the accolade of the world’s first railway locomotive engineer. However, the cast-iron plates, which formed the rails, cracked under the weight of the engine in several places.

Trevithick then built a similar locomotive at Gateshead for use on the Wylam Colliery waggonway in 1805, but the mine owners decided not to buy it, probably because their railway’s rails were made of wood, so, it was converted to blow the furnace, as a stationary engine.

In 1808, Trevithick turned out his last steam railway locomotive, Catch-Me-Who-Can, which ran on a circle of track in fairground fashion for public gaze – ironically very near to the site of the future Euston station. With its carriage, it became the world’s first, steam passenger train.

Trevithick made little money from his railway experiments, and turned away from steam traction for the last time, sadly accepting that the horse and cart, whether on rails, roads or a canal towpath, still reigned supreme.

It was unlikely that Trevithick ever envisaged a national network of railways; he merely intended his engines to replace horses on the short tramways, which served canals, harbours and other transhipment points for industrial products or supplies.

Not everyone was as pessimistic. In 1812, the need for a serious alternative to horses arose out of the relentless demands for their supply and use in the continuing war between Britain and Napoleon.

England’s north-east, like Cornwall, had no connection to the national waterway network, so, another form of bulk transport was needed, and fast.

Christopher Blackett, who owned Wylam Colliery, failed to persuade Trevithick to have one last attempt at railway engines. Meanwhile William Hedley and Timothy Hackworth obliged, and with the aid of engine-wright Jonathan Forster, built the legendary eight-wheeled, eight-ton Puffing Billy for the mine’s tramway system, drawing much inspiration from Trevithick’s designs.

George Stephenson, who was later to become a close friend of Isambard Brunel, built his first engine in 1815, and the world’s first steam-powered public line, the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which Stephenson helped engineer, opened in 1825.

Among Brunel’s circle of friends was another Cornishman, Sir Humphrey Davy, a chemist who discovered the anaesthetic effect of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) and invented a safety lamp for use in coal mines, allowing deep seams to be mined, despite the presence of methane. Considered to be Britain’s leading scientist, in 1812 he was knighted by George III.

Davy and his assistant, Michael Faraday, found that several gases could be liquefied by a combination of low temperature and very high pressure, and in 1823 Marc Brunel became convinced that their discoveries could form the basis of a more efficient type of engine to rival the steam variety.

For much of the ensuing decade, Marc and Isambard spent their time experimenting with pressurised carbonic gas, in a bid to break new ground in a fertile age for new inventions, to produce what they called the Gaz Engine, but despite throwing £15,000 of the father’s money at the project, it could not be made to work. This would be a rare example of a Brunel failure, despite their perseverance.

Railways would have to wait, however, for in 1823, Marc Brunel began work on what would be his greatest project of all – the Thames Tunnel.