Chapter 3

THE THAMES TUNNEL

The Eighth Wonder of the World

We Britons are by and large a modest bunch, maybe too modest for our own good. For instance, had it been a US citizen who had invented the world’s first steam locomotive, and not Richard Trevithick, we would never hear the last of it.

Our nation oozes heritage out of every orifice, yet so much of it we have passed by, or let disappear without trace, before we realise its importance.

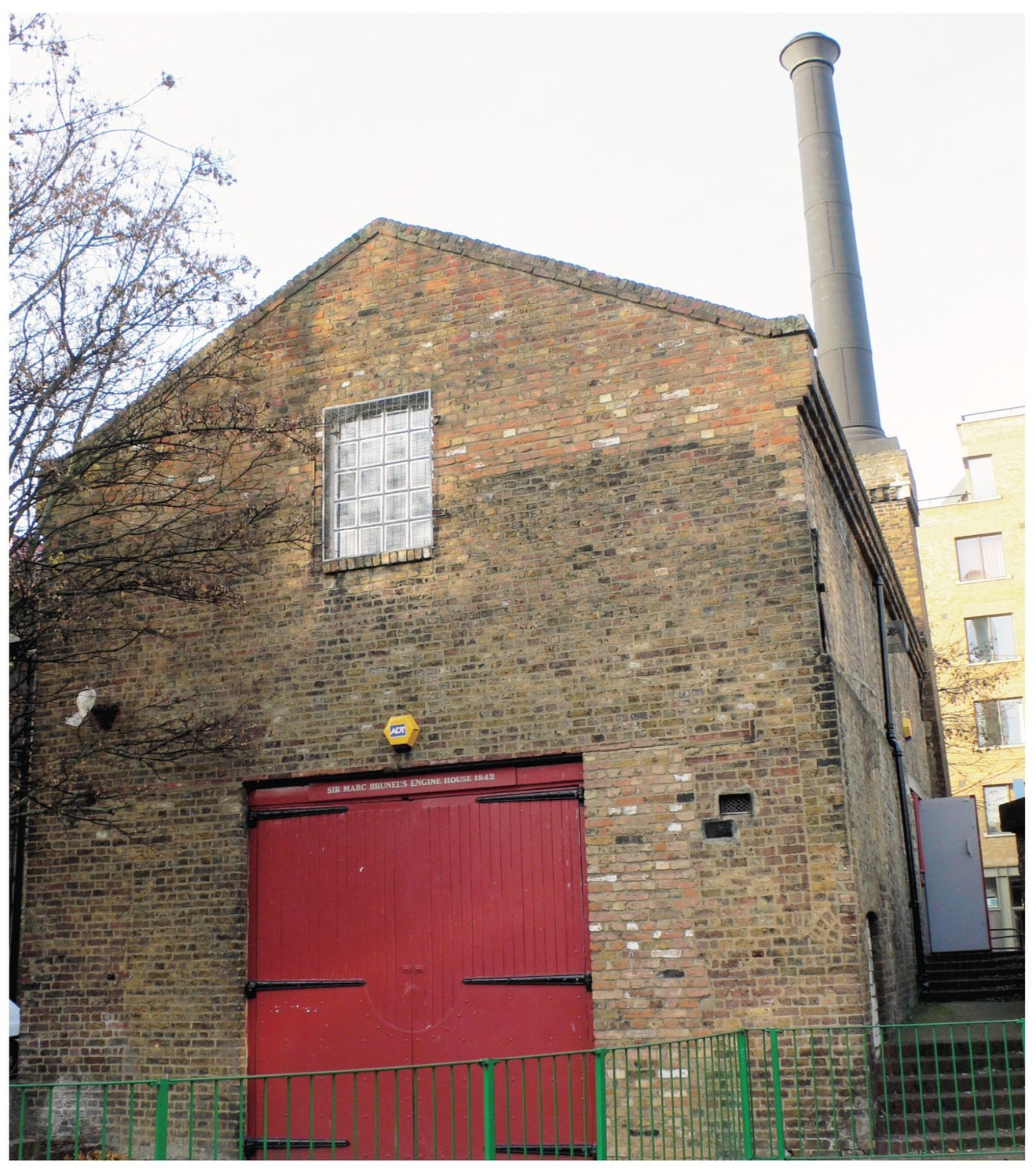

In a back street in London’s Rotherhithe stands a small, yellow-stone industrial building, which stands out only because it has a tall chimney and unlike the surrounding properties, is not a domestic dwelling.

Those intent on visiting the capital to see the Tower of London, Buckingham Palace or St Paul’s Cathedral would not give it a second glance, and in any case, Rotherhithe is well off the beaten tourist track.

Yet, in so many ways, this structure is far more important than any of the aforementioned, at least in terms of the development of the modern world.

Now known as the Brunel Museum (formerly the Brunel Engine House), this humble building in Railway Avenue should be a first port of call, for it is a veritable mine of discovery – if only for the fact that it was built to drain the world’s first public, underwater tunnel.

Today tunnels beneath the Thames are commonplace, and building one would hardly grab the headlines. We have tunnels for underground trains, road traffic, essential services like gas, water and electricity, telecommunications and even a secret network of corridors between government buildings, it is believed.

However, back in the 19th century, when Britain led the world in technology, the Thames Tunnel was hailed as its eighth wonder, and with much justification.

To gauge its importance, we have to imagine ourselves back in the London of 200 years ago, when the sole means of crossing the river was by way of the medieval London Bridge, or by using ferrymen.

The interior of the tunnel, following refurbishment between 1995-98, during which most of it was lined with an 8in-thick concrete shell. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

The River Thames above the Thames Tunnel. ROBIN JONES

As the tunnel is an International Landmark Site, when it was refurbished in the 1990s, four of the original arches were preserved as built. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

The first enclosed docks opened in 1802 on the Isle of Dogs, and within 20 years it had been followed by the East India Docks at Blackwall, London Docks at Wapping, and Surrey Docks at Rotherhithe. Downstream from the Tower of London, both sides of the river were crammed with warehouses and factories, but the river placed a major stumbling block to lines of communication and trade.

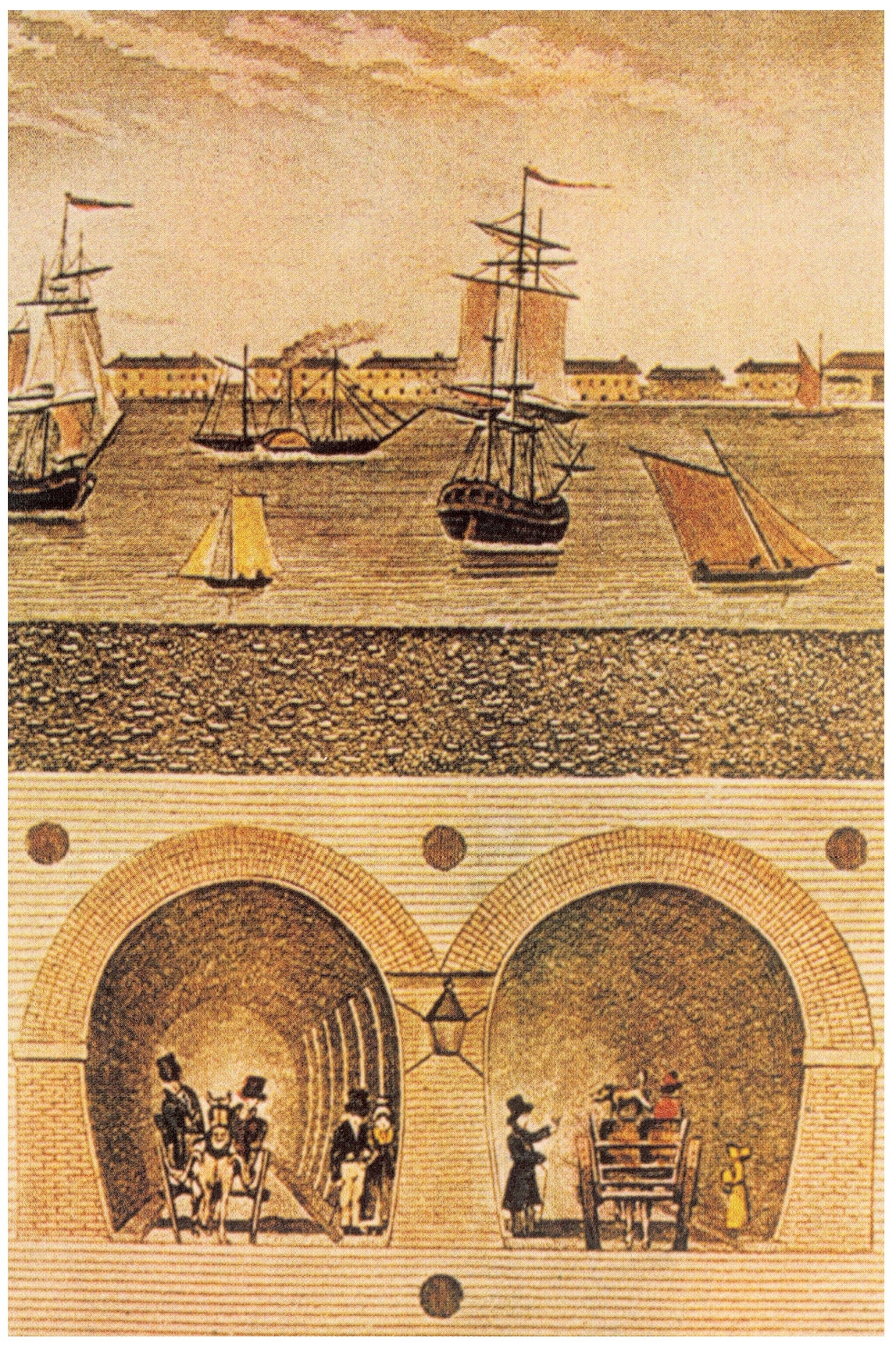

The volume of traffic on the water caused much congestion, and it was obvious that a new physical crossing would be needed. However, a bridge would have to be high enough to clear the masts of ships, and the technology for a lifting structure on the lines of the later Tower Bridge had not yet been developed.

Thoughts turned towards the building of a tunnel, but no blueprint for the construction of one was readily available.

It was said that in the ancient world, the Assyrian queen Semiramis had the River Euphrates at Babylon diverted, so a tunnel could be built beneath it, for her personal use, and some believed that the Romans bored beneath the sea off Marseille.

In recent times, tunnels under the sea for mining purposes, off the west coast of Cornwall and beneath the estuary of the River Tyne had been hacked through rock, but these were not built for public use and did not have to contend with the soft ground normally found under riverbeds. Master that single problem – and a Thames tunnel could be built.

In 1798, Ralph Dodd, the designer of the Grand Surrey Canal, proposed a 900-yard tunnel between Gravesend and Tilbury and obtained sufficient money to sink a shaft, but was not able to raise further funds after geological problems were encountered.

Four years later, Robert Vazie drew up plans for a shorter tunnel on the narrower part of the river between Rotherhithe and Limehouse, and joined forces with none other than fellow Cornish mining expert, Richard Trevithick, to build it under the auspices of the Thames Archway Company, which was duly founded in 1805.

Work on digging a 5ft-high pilot tunnel at a depth of 76ft feet began at Rotherhithe in August 1807 and progressed at the rate of 6ft per day, speeding up when Trevithick took sole charge.

After the tunnel crossed the halfway point, a layer of rock was encountered, beyond which lay quicksand – which in turn brought water flooding into the tunnel, causing part of the roof to collapse.

Undeterred, the miners pressed on, draining the tunnel after blocking the hole. There were more inrushes of water, however, including one, which nearly drowned Trevithick on 26 January 1808, after the low-tide mark on the north bank of the Thames had been reached.

Trevithick, who left only when the water was up to his neck, repaired the breach by dumping clay onto the riverbed before pumping the tunnel dry.

To counteract such problems, he devised a new method by which the tunnel would be built from above. The miners would work inside a series of cofferdams and lay a tunnel, comprising of cast-iron sections inside their trench.

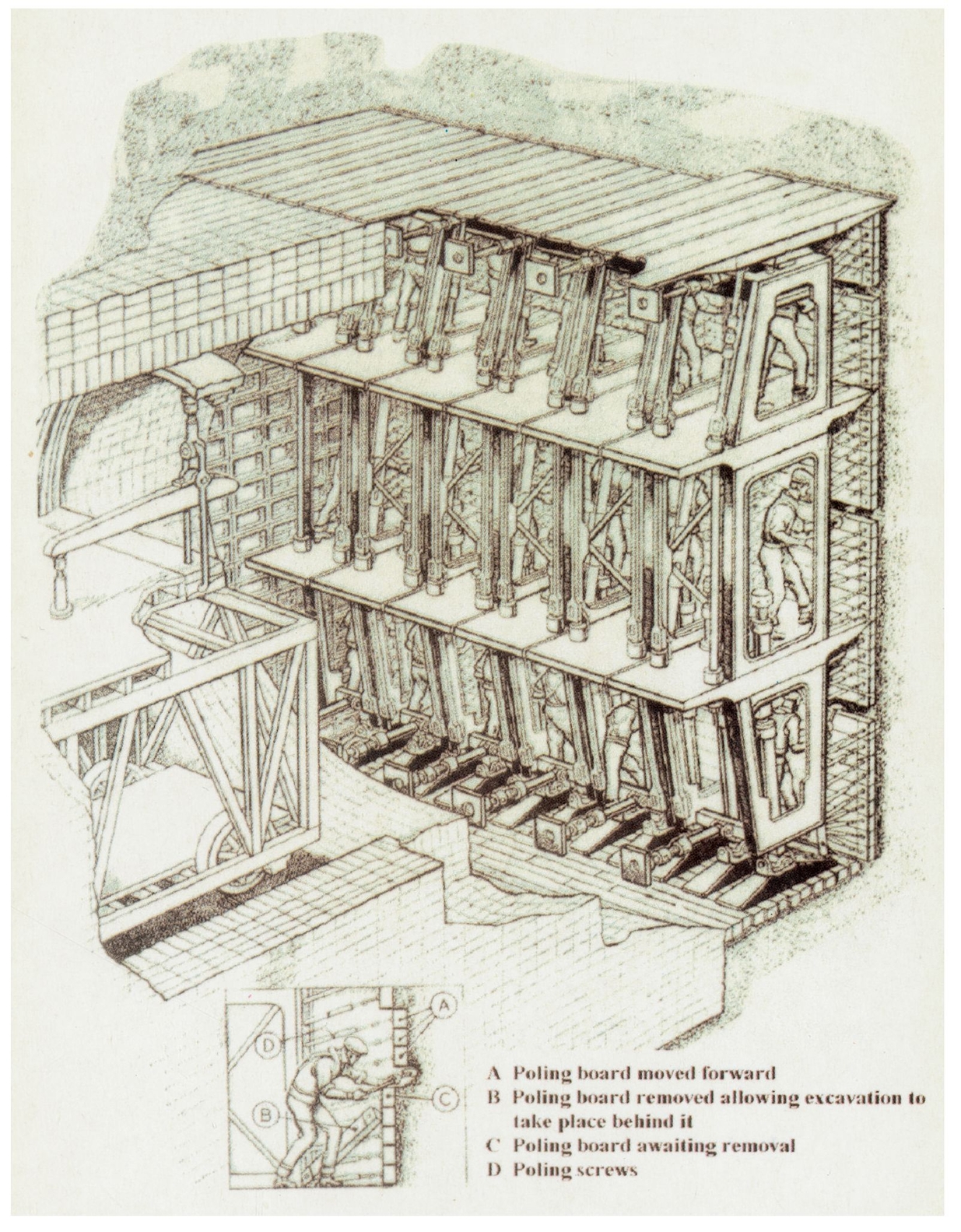

A contemporary sketch of Brunel’s tunnelling shield.

However, it had never been done before, and his company’s directors and financial backers were having none of it, instead offering a prize of £500 to anyone who could find another means of finishing the tunnel. When none of the 49 offered solutions were deemed workable, the tunnel was abandoned, with less than 200ft to go.

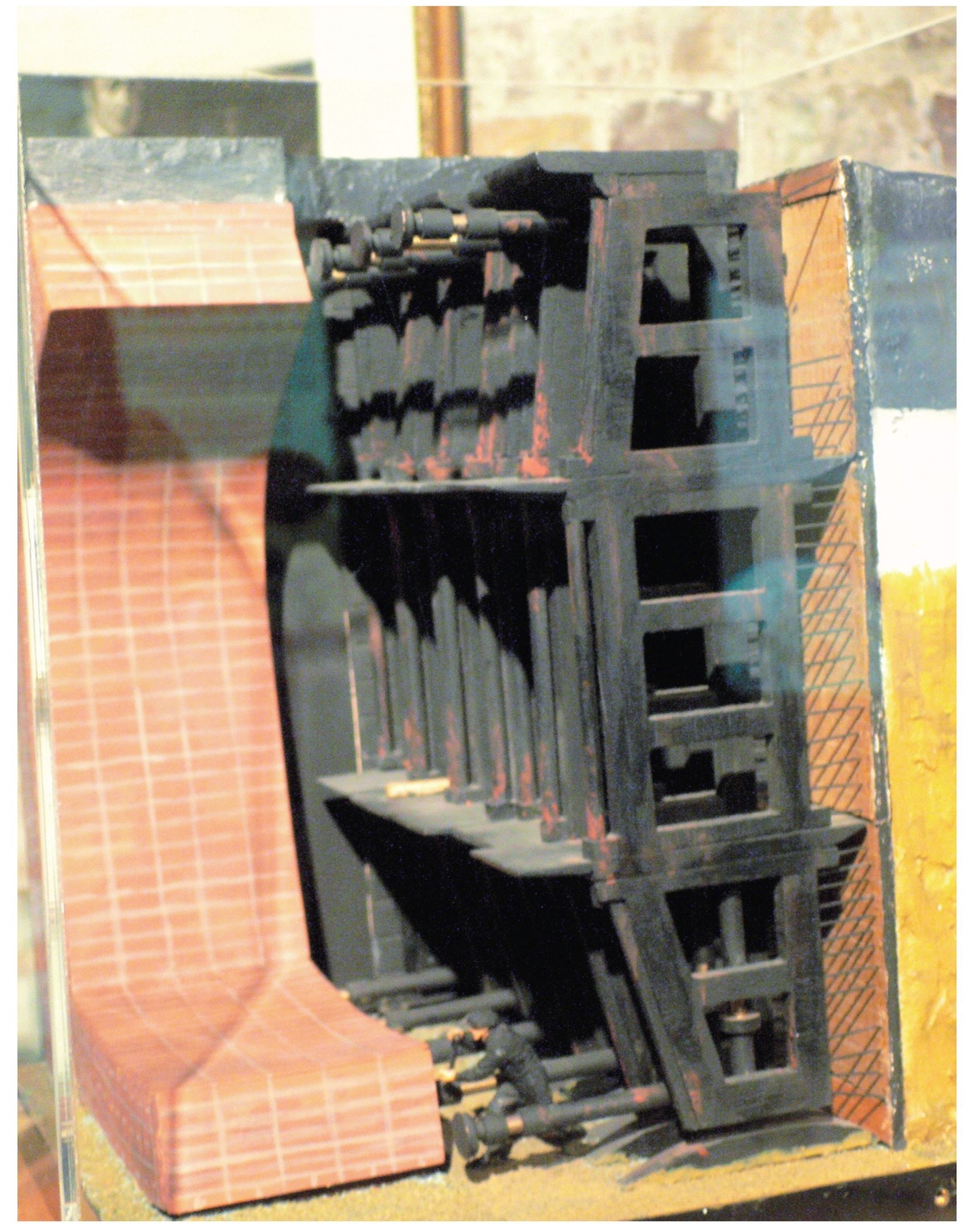

A model of Marc Brunel’s revolutionary rectangular tunnelling shield, as displayed in the Brunel Museum at Rotherhithe.

In 1818, however, Marc Brunel patented a tunnelling shield; a device that made it possible to safely bore through water-bearing strata such as the offending quicksand.

While Marc had been engaged with his sawmill at Chatham Dockyard, he studied the destructive shipworm, teredo navalis, which ate its way through timber with its hard, horny head, leaving a coating around the ‘tunnel’ it had gnawed.

He had already looked at the possibility of a tunnel under the River Neva for the Russian Tsar, and in doing so had brought himself up to speed with the technical problems that would be involved.

His revolutionary shield consisted of 12 separate numbered cast-iron frames, comprising a total of 36 cells in which a miner could work independently of the others.

The propulsion for the device was provided by a screw, which drove the shield forward in 4.5-inch steps, the width of a brick.

The frames with the odd numbers were worked first, and as each board was replaced, it was braced with polling screws against the adjacent cell. When all the boards had been worked down, the shield could move forward and the screws were replaced. The main frame would be worked forward by the use of screw jacks bracing against brickwork behind. Each foot of tunnel required 5500 bricks to be laid.

Brunel’s 1818 patent had detailed a circular boring shield, with long rotary cutting blades at the front to excavate the earth, and a cylinder supporting the top and sides, until a brick lining could be built.

However, during his time in the debtor’s prison, he realised that it could not be implemented with the steam-engine technology available at the time, and so opted for a rectangular shield instead, with all the digging done by hand, in the time-honoured way.

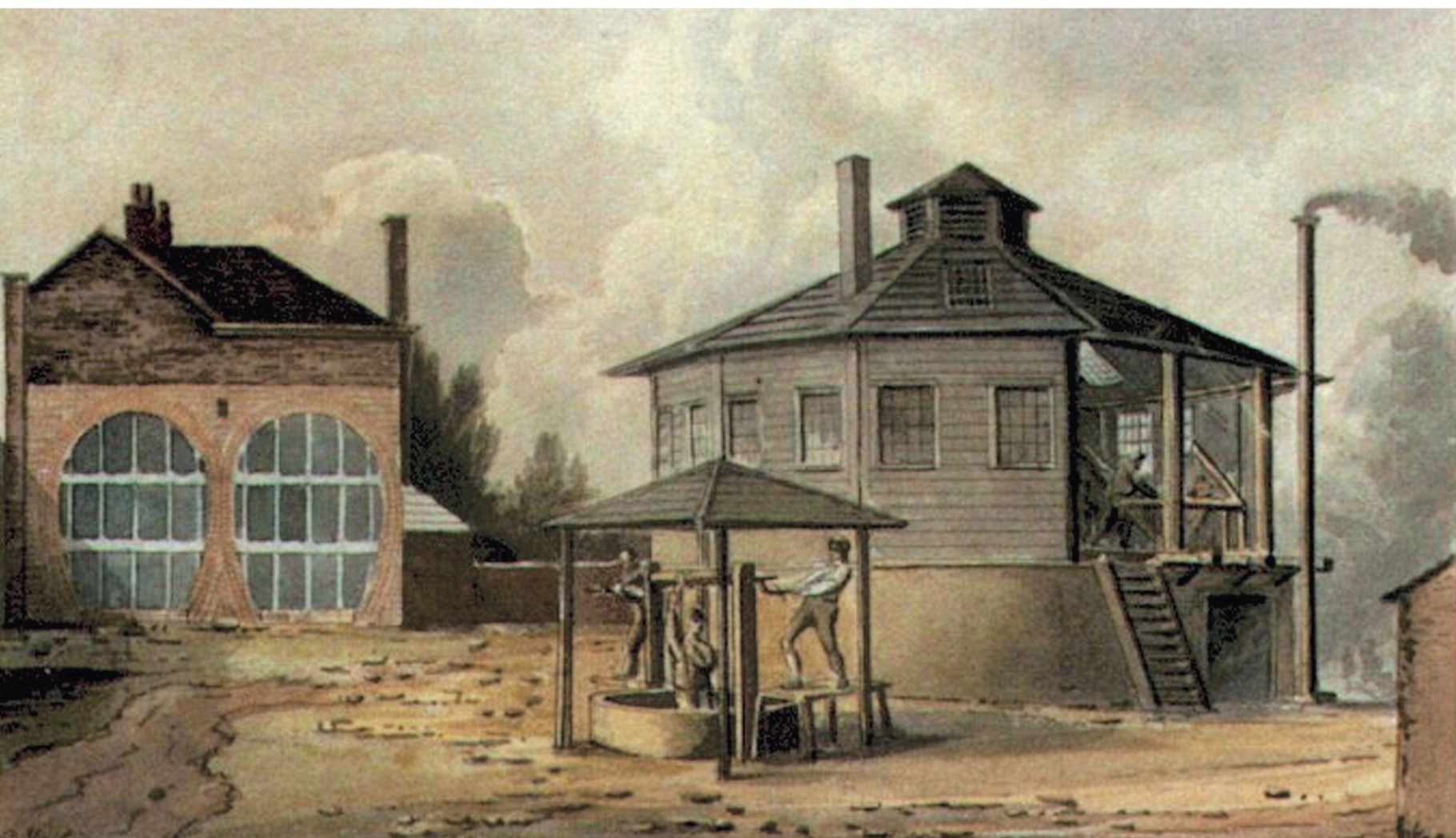

A Yates’ watercolour sketch of the top of the Thames Tunnel shaft at Rotherhithe and the engine house next to it, built by Marc Brunel in 1842 and now a scheduled ancient monument. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

Marc’s old ally the Duke of Wellington lent his support for a fresh scheme to burrow beneath the river, and the Thames Tunnel Company was formed in 1824, with Brunel as engineer.

A shaft was sunk at Rotherhithe on 2 March 1825, using a groundbreaking method of building its 42ft-high, 900-ton brick cylinder at ground level and then allowing it to sink under its weight down the hole excavated below.

The red-brick Brunel Engine House now contains a museum – and offers the public regular tours through the Thames Tunnel by underground trains on the East London Line. Dating from 1842, the building was designed by Marc Brunel to contain the steam engines, which drained the tunnel, and next door stands the top of the Rotherhithe tunnel shaft. The museum contains the sole-surviving, horizontal V, stationary steam engine built by J&G Rennie. ROBIN JONES

A medallion struck to mark the opening of the Thames Tunnel in 1843. ROBIN JONES

By July, the shaft had been sunk to a depth of 65ft, allowing the assembly of the shield to take place.

By November, tunnelling towards the Thames had begun, with Marc optimistic that the project would be finished within three years.

Isambard was appointed acting resident engineer on April 1826, and given the job permanently, when he was just 20, on 3 January the following year.

He would stay below ground for 36 hours at a time to supervise the tunnelling, and became ill in the process.

The company directors, eager to make a quick buck, capitalised on the publicity that the project was generating, by allowing paying sightseers inside the first 300ft of the tunnel from February 1827.

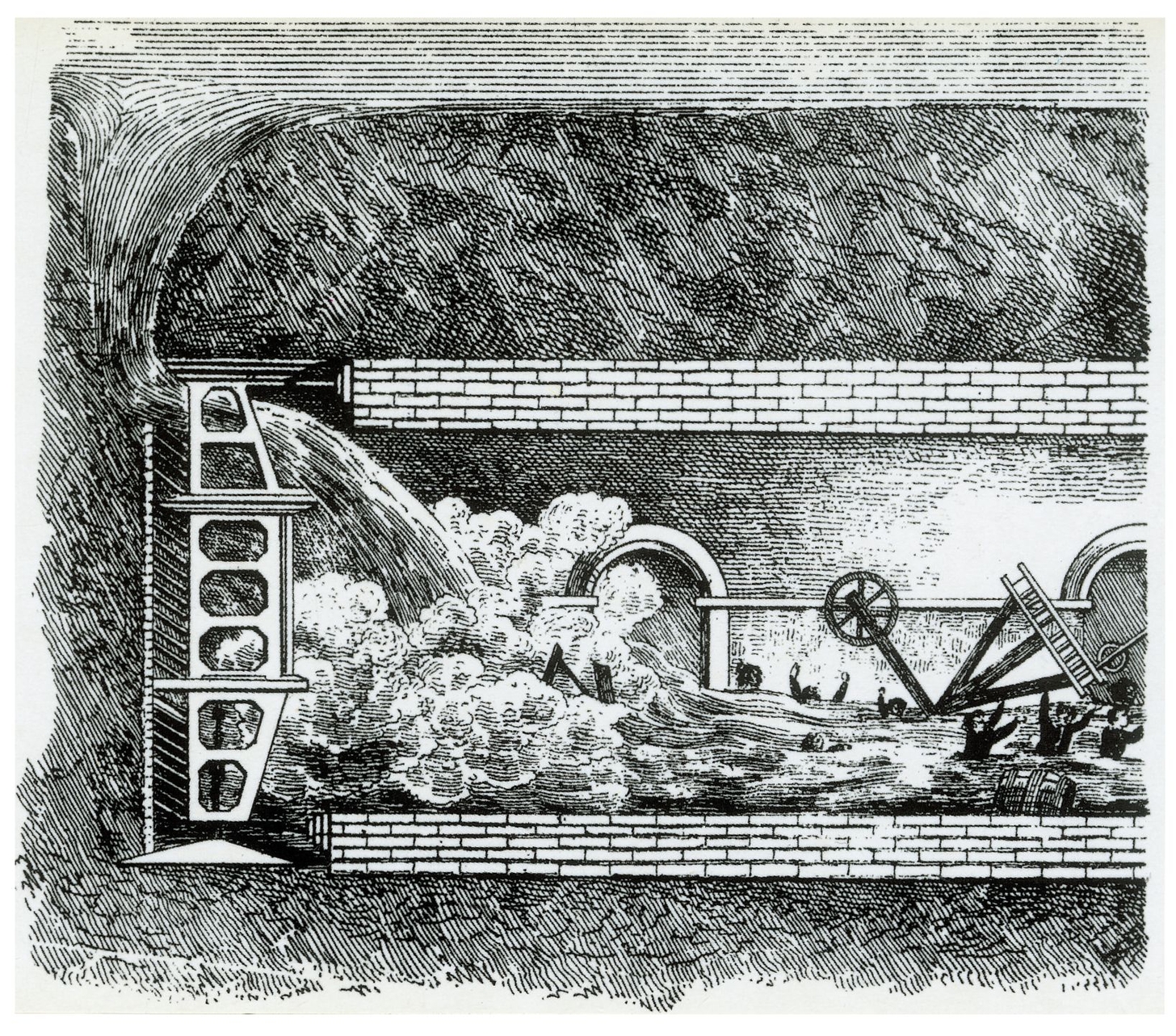

The project, however, would not progress as efficiently as Marc predicted. The first of five major floods took place on 18 May 1827, caused by tunnelling too close to the riverbed. Visiting the bottom of the river in a diving bell, as crowds watched from the riverbank, Isambard realised that gravel dredgers had caused the problem.

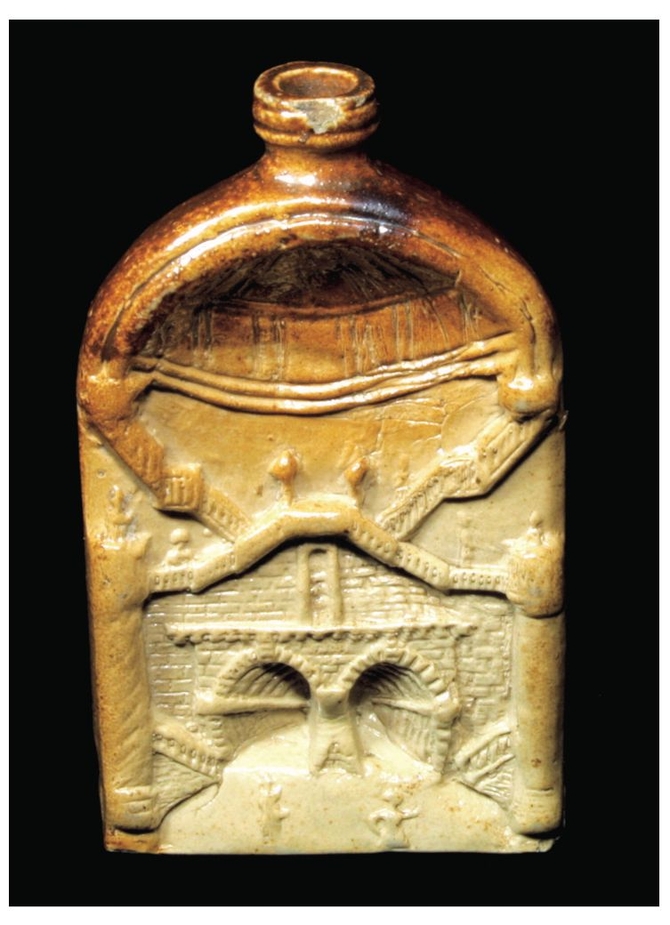

Two early souvenirs celebrating the Thames Tunnel: a lacquered box and a hip flask. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

A contemporary, cutaway diagram of the Thames Tunnel. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

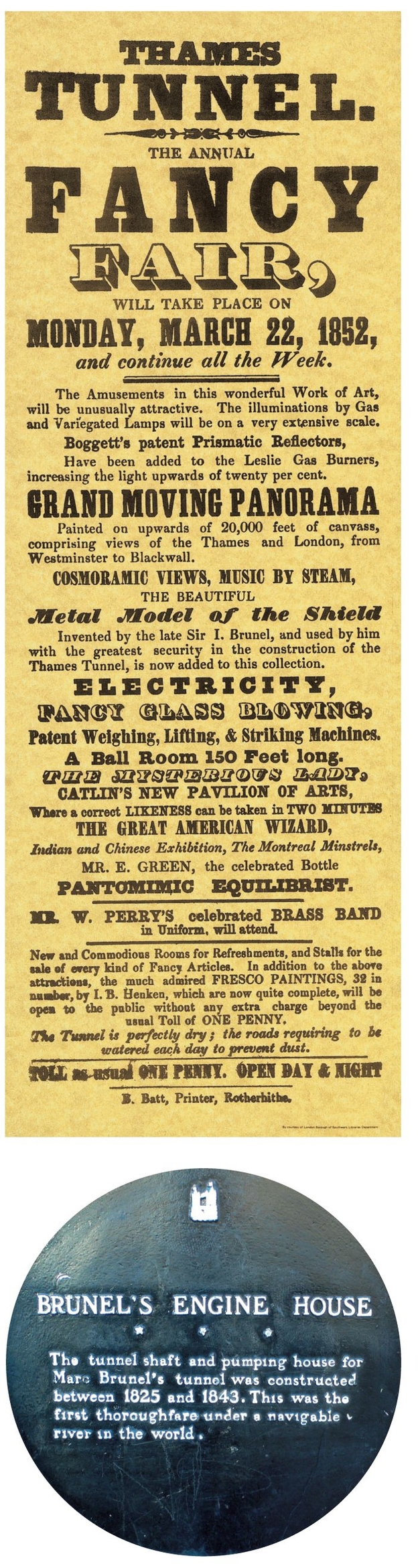

A handbill advertising a fair in the Thames Tunnel. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

A 10,000sq ft canvas sheet was ordered by Marc to be placed over the breach, weighed down with chains around its edges, so that 4000 bags of clay could be laid on it to fill the depression, before the floodwaters could be pumped out.

Regardless of the danger, tourists were taken inside the tunnel by punt to inspect the damage as it was being repaired. One miner was drowned when the punt overturned in the flooded workings, becoming the second fatality on the project, the first being when a drunken workman had fallen down a shaft.

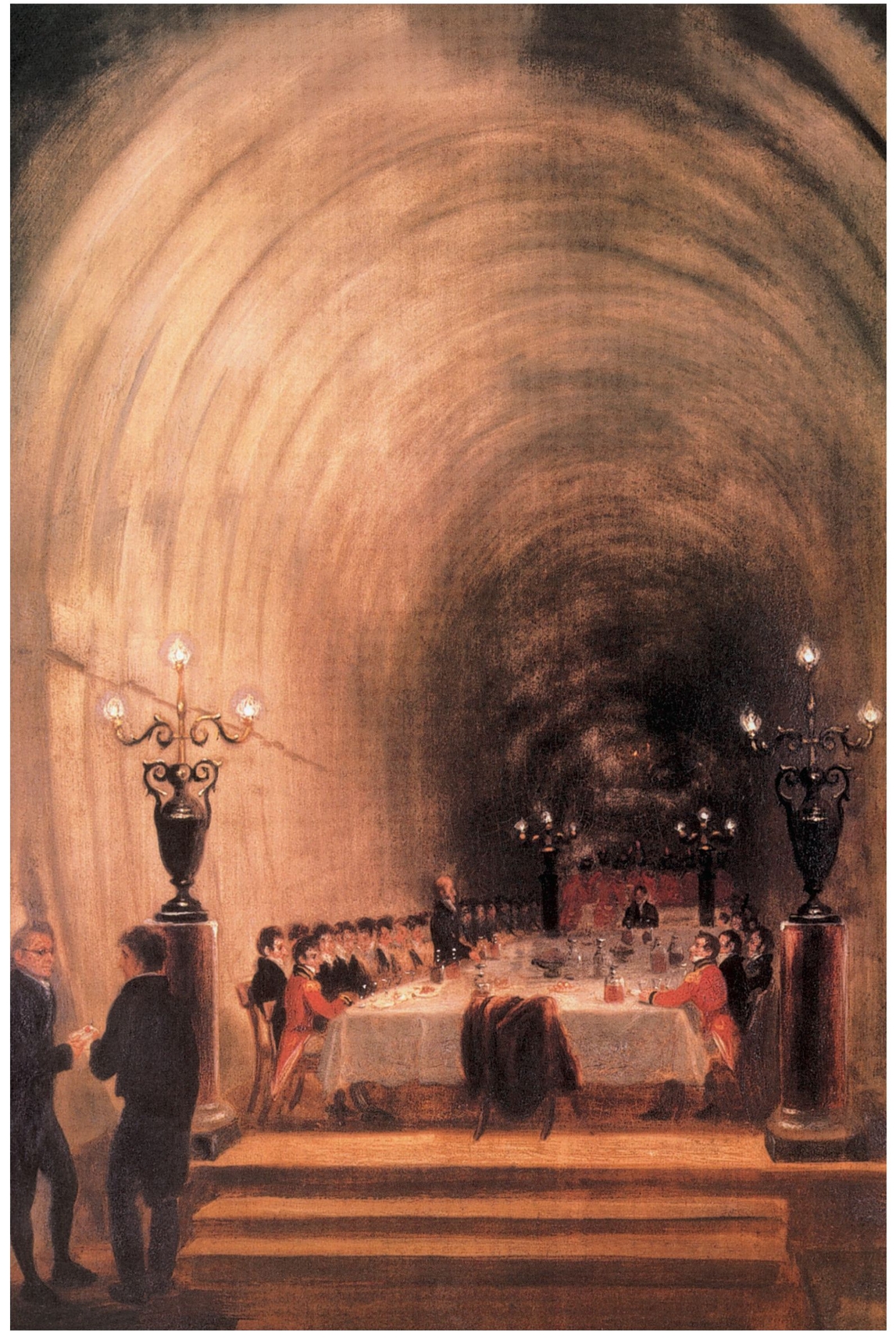

The tunnel was cleared of water by November, and Marc was so pleased that he organised a banquet in the tunnel to celebrate. Up to 50 guests sat around a linen-covered table as the tunnel was illuminated by four massive candelabras, as the band of the Coldstream Guards provided musical entertainment. Around 120 miners and bricklayers also attended, and Isambard (Marc was not present) was presented with a pickaxe and shovel.

The miners faced an extremely hazardous and unpleasant task, despite the use of the innovative shield, while assistant engineer Richard Beamish had lost an eye during the work.

Not only was ventilation difficult, and there was the threat of drowning if breaches occurred, but there was the ever-present danger of both poisonous gases and cholera from the foul Thames water. The river at this time was little better than an open sewer, as it was to be many years before Joseph Bazalgette implemented his effluent drainage system for the capital. A fever that caused blindness was rife among the workers and in November 1825, Marc also fell ill.

His son also narrowly escaped death when water burst into the tunnel again, on 12 January 1828. Having managed to free a timber beam, which trapped his leg, Isambard found that the workmen’s stairs were blocked by miners panicking to escape – so he turned and headed for the separate visitors’ stairs instead.

The famous banquet held inside the incomplete tunnel in 1827. IRONBRIDGE GORGE MUSEUMS

A huge wave of water swept through the tunnel, swamping Isambard – but also carrying him to safety at the top of the 42ft Rotherhithe shaft. However, six workmen, including two who had been working with Isambard when the inundation occurred, died.

The flood led the directors to abandon the tunnel, which by then had reached 605ft. Not good news at a time when the country was suffering from an economic slump; the tunnel had drained all the available finances, after 30 times the amount of clay used to repair the first breach had been dumped on the riverbed to allow the workings to be pumped dry again.

Wellington again offered his support; publicly appealing for £200,000 to be subscribed to finish the job, but only £9,600 was raised.

A contemporary sketch of floodwaters breaking through into the tunnel workings. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

So, in August that year, the tunnel face and shield were bricked up, but the sightseers were still allowed a glimpse inside the workings, by means of a mirror. The Times dismissed the project as the ‘Great Bore’.

Meanwhile, Isambard’s injuries had been far worse than he first thought, and he spent several months convalescing in Brighton, during which time he suffered the first of a series of haemorrhages.

Marc continued to rally support for the tunnel and designed a better shield. He suffered a heart attack in November 1831, but carried on regardless, so determined were he and his son to finish the project.

At last, in December 1835, Wellington and another of Marc’s friends in high places, Lord Althorp, approved a loan of £270,000 – and boring restarted on 24 March 1835 – by which time Isambard had become heavily involved elsewhere, on steamship and railway projects.

There were further major breaches of the riverbed on 23 August 1837, 3 November 1837, when a worker sleeping in the shield was drowned, and on 20 March 1838.

On 22 August 1839, the tunnel reached the low-water mark on the Wapping side, and in June the following year, work on sinking a shaft on the north bank began.

For his work on the project, Marc Brunel was knighted by Queen Victoria, on 24 March 1841. However, at the age of 72, the tunnel work had already taken its toll on his health.

Finally, on 16 November 1841, engineer Thomas Page ran excitedly to Marc’s house with the news that the tunnel had at last reached the shaft on the north shore.

Finances had been drained to the extent that the proposed spiral road ramps to take traffic into the tunnel could no longer be afforded. Instead, as a result, it would only be accessible to pedestrians by means of winding staircases at either end.

It was like spending your life savings on building a Rolls-Royce, to then only be able to fit a seat for the driver. Without the carriageways and the ability to claim tolls from road traffic, the tunnel would never be profitable.

Sightseers were allowed into the northern shaft for the first time in August 1842, and after Marc suffered a stroke on 7 November, Isambard took over many of his dealings with the company’s directors regarding engineering matters.

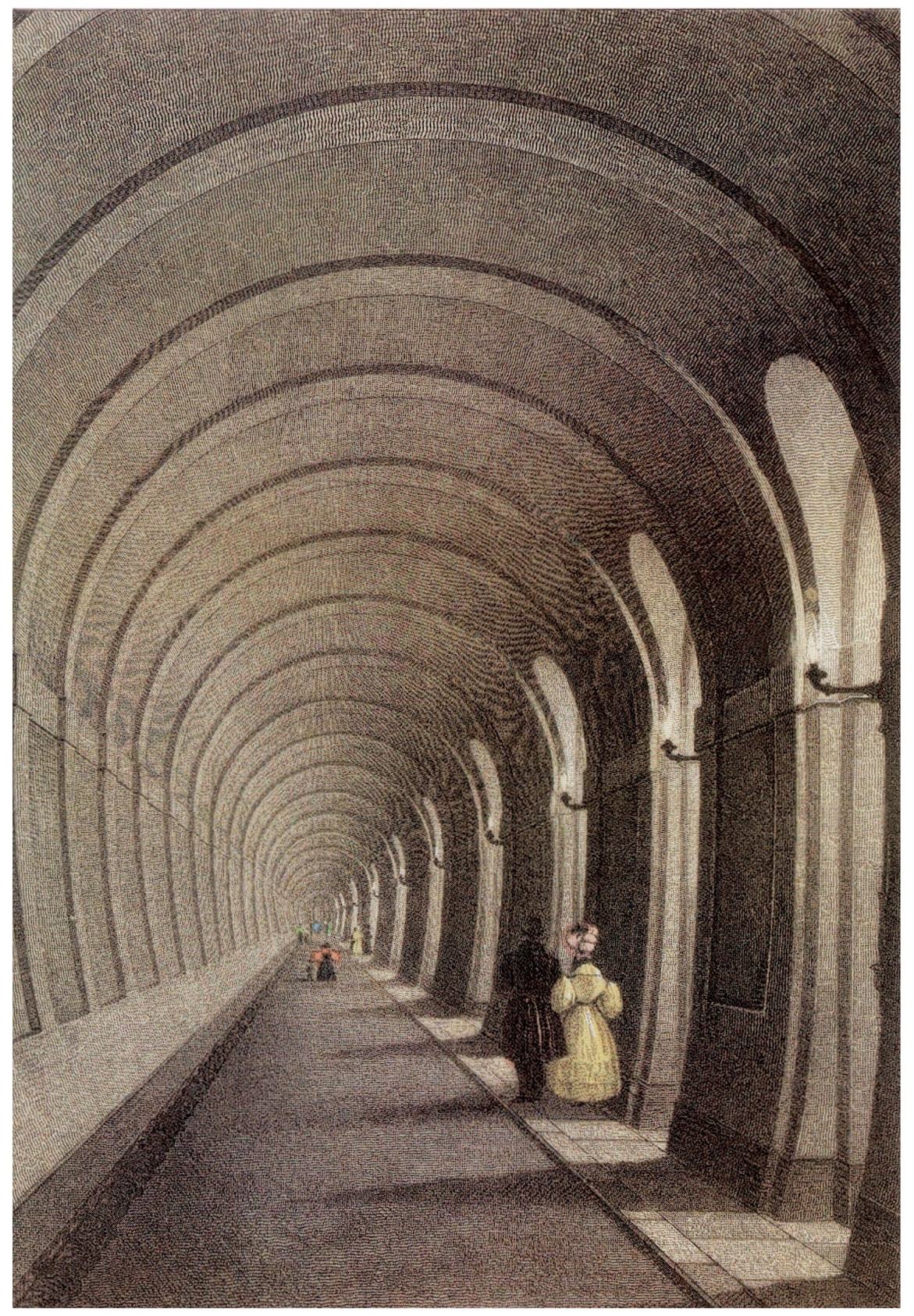

The completed two-bore tunnel – which has a roof only 14ft below the riverbed and is 1200ft long between both shafts – was finally opened amid much fanfare on 25 March 1843.

Thames watermen flew black flags from their vessels because they knew that their trade was now at an end.

However, others had paid a much higher price. While the official death toll among workers was only seven, it had been suggested that the ‘real’ death toll was likely to have exceeded 20 and may even have been closer to 200, taking into account the consequences of work-related illnesses, and illness caused by working in the stifling atmosphere.

Queen Victoria gave the tunnel her seal of approval when, with little warning, she turned up at Wapping by royal barge on 26 July 1843, with her consort Prince Albert, and accompanied by Page (who was standing in for Marc Brunel who was away on business) and company directors, walked the full length of the tunnel from Wapping to Rotherhithe and back.

About 50,000 people walked through the tunnel during the first two days of operation, and more than a million people used it in the first four months. People travelled from far and wide to see what was heralded as a great marvel, and a roaring trade in souvenirs – trinket boxes, whisky flasks and jugs, and paper peepshow models, a distant forerunner of today’s hugely popular red, pottery telephone boxes, black cabs and model buses – quickly sprang up.

However, it had its critics, not least of all those who found the 99 steps at each end too much to bear – and who preferred the old ferries. The American novelist, Nathaniel Hawthorne, was less than impressed by his visit and wrote in 1855:

“It consisted of an arched corridor of apparently interminable length, gloomily lighted with jets of gas at regular intervals… there are people who spend their lives there, seldom or never, I presume, seeing any daylight, except perhaps a little in the morning.

“All along the extent of this corridor, in little alcoves, there are stalls of shops, kept principally by women, who, as you approach, are seen through the dusk offering for sale multifarious trumpery. So far as any present use is concerned, the tunnel is an entire failure.”

Sadly, the tunnel quickly became the den of prostitutes, pickpockets and ne’erdo-wells in need of a free place to sleep at night. Furthermore, it did not solve the traffic problem of London, as trade and population continued to soar, and it was soon clear that more river crossings would be needed.

After the tunnel was finished, Marc and his wife moved from Rotherhithe to Park Street, a short walk away from Isambard’s house in Duke Street.

Marc died on 12 December 1849, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. Sophia moved in with her son, and lived until January 1855.

Three years before his death, Marc was said to have approved of his tunnel being converted for use as a railway. In 1865, it was sold to the East London Railway for £200,000 and tracks were laid through it so that it could carry steam trains between Wapping & Shadwell station and New Cross. The first services ran on 7 December 1869.

The tunnel eventually became part of the electrified underground system, and is still in daily service today.

In 1869, work on building a second tunnel beneath the Thames began – the 1235ft Tower Subway, a 7ft-diameter, iron tube which runs 18ft below the riverbed between Great Tower Hill on the north side of the river, and Tooley Street on the south.

William Tombleson’s c1834 painting A Perambulation Through The Thames Tunnel. BRUNEL ENGINE HOUSE

A smaller affair than Brunel’s original, it was designed to convey a narrow gauge, cable-hauled railway and opened on 12 April 1870. The single carriage was insufficient to carry the volume of passengers wanting to cross the river, and so the line was closed on 7 December that year with the tunnel converted into a pedestrian subway, reached by 96 steps. Nonetheless, the Tower Subway has staked its claim to being the first purpose-built tube railway tunnel.

It was, however, predated by the Thames Tunnel by 20 years, and it was the Brunels who proved to London that crossing the Thames underneath the river was possible.

Their innovation, improved by the methods used by James Henry Greathead and his cylindrical boring shield (more akin to the circular shield in Brunel’s 1818 patent than the rectangular one used for the Thames Tunnel) in building the Tower Subway, laid firm foundations for the London underground railway network, without which London would quickly grind to a standstill.

In turn, the availability of safe, soft-ground tunnelling technology inspired cities throughout the world to build their own underground systems, and even the construction of the Channel Tunnel has roots in Marc Brunel’s original shield design.

Many accolades therefore must go to Marc Brunel, his son and the Thames Tunnel. However, the Brunels could – and should – have been beaten by Trevithick a third of a century earlier.

The Cornishman’s plan to complete his tunnel by laying cast-iron pipe sections behind cofferdams may not have won the support of his company, but has since been shown to work, and in recent times has been employed in the building of the San Francisco BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) tunnel and the Detroit river tunnel, for instance.

In later life, after abandoning his railway locomotive ventures, Trevithick sought his fortune in the mines of South America, along with many of his fellow Cornishmen. He did not find it, returned home in poverty, died in Dartford on 22 April 1833, and was buried at a now-unmarked grave in the town’s churchyard.

A year later, the Bodmin & Wadebridge Railway became Cornwall’s first steam-hauled line. In the decade that followed, a young engineer was to make mind-blowing advances in the field of railways, linking Trevithick’s home county to the capital in the process. His name was Isambard Kingdom Brunel.