Chapter 4

REACH FOR THE SKY

Bristol and its Suspension Bridge

Exertions with actresses! Isambard Brunel’s biographers gave that reason as to why he suffered a major relapse during his convalescence in Brighton, where he had gone to recover from the extensive injuries sustained during the aforementioned collapse of the Thames Tunnel.

Whatever the reason, he was despatched first of all to a relative’s house in Plymouth and then on to the genteel Bristol area of Clifton, in a bid to accelerate his recuperation. History would never look back.

Once there, Isambard, still just 22, found he was equally as inspired by the sight of the limestone Avon Gorge, as he had been by the ladies of Brighton.

For him, it was a classic case of being in the right place at the right time.

In 1753, William Vick, a local alderman, left £1000 to be invested until such time as it had grown into £10,000 – when it was to be spent on a bridge spanning the gorge.

By 1829, the figure of £8000 had been reached, and a committee was set up not only to raise the remaining £2000 but to hold a competition to find the best design, with a prize of 100 guineas for the winner. And Isambard was right on the doorstep.

He eagerly presented the Clifton Bridge Committee with a choice of four designs, all involving a suspension bridge, with spans varying from 870ft to 916ft – with more than a little help from father Marc regarding the finer detail.

The great canal and bridge builder, Thomas Telford, was called in to judge the contest, which attracted 22 entries.

However, Telford dismissed them all, including Isambard’s design, saying that his proposed span was too long – citing his own troubles with lateral movement caused by wind on his own Menai Strait suspension bridge, which was less than 600ft wide.

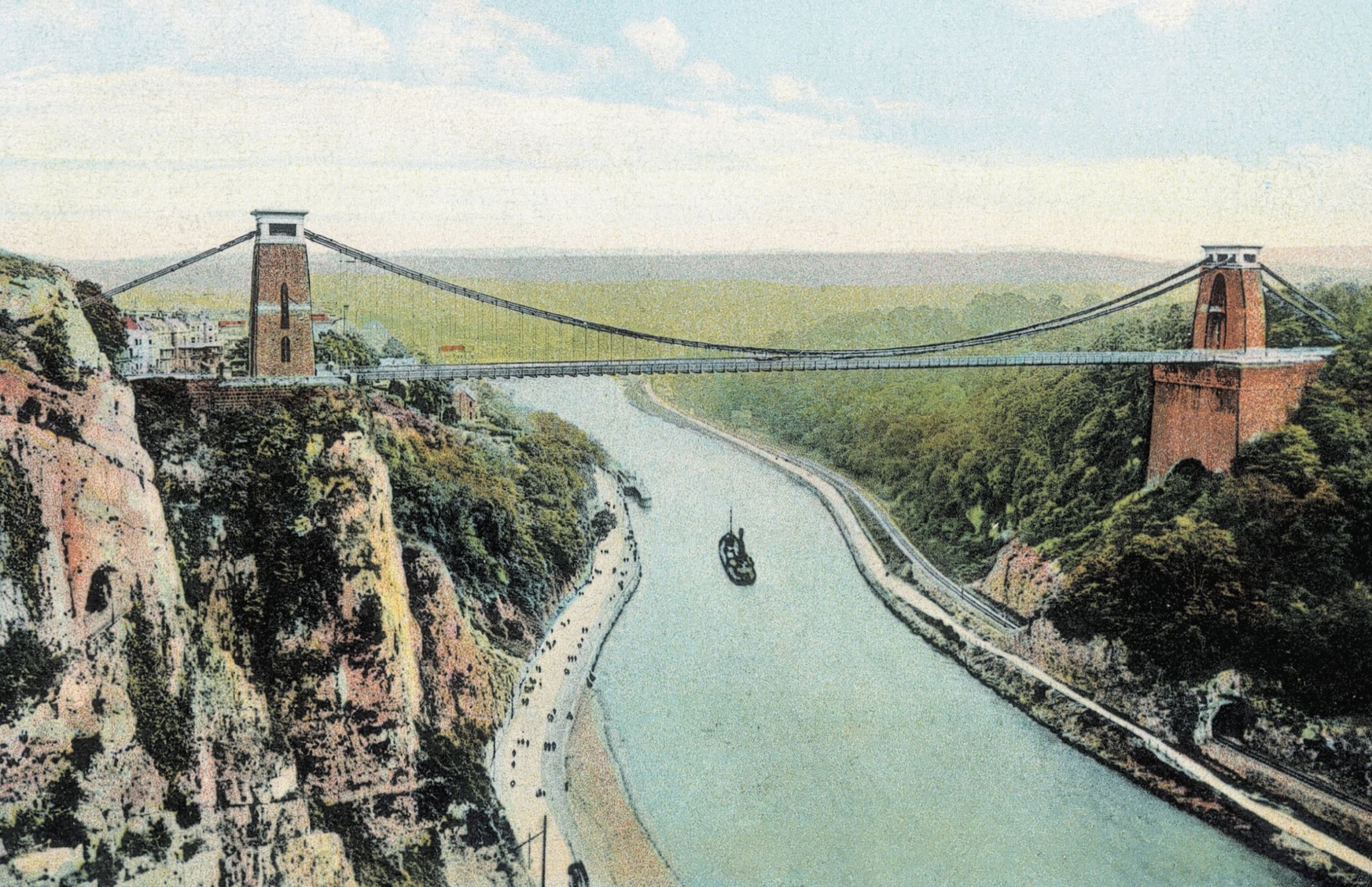

Clifton Suspension Bridge – still magnificent more than 140 years after it was completed. DESTINATION BRISTOL

The committee then asked Telford to draw up a scheme of his own, and he produced plans for a suspension bridge, supported by two ornate Gothic towers set into the bed of the gorge.

A furious Isambard poured scorn on the Telford design in a scathing letter to the bridge committee, and then, his finances dwindling, set off to the north of England to look for work.

He was turned down for the post of engineer to the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway in favour of Francis Giles, who at one time had tried to replace Marc Brunel as engineer of the Thames Tunnel.

However, his disappointment was assuaged somewhat when, on 10 June 1830, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, in recognition of his work on the tunnel, his plans for the Clifton bridge and his experiments with the Gaz Engine. He also found a rather unglamorous job to earn some desperately needed income – draining marshland at Tollesbury, in Essex.

Suddenly, on 16 March 1831, the bridge committee announced that Isambard’s scheme had won a second contest, although to allay fears aroused by the apparently jealous Telford, its members agreed to (unnecessarily) spend an extra £14,000, to add a stone abutment rising out of the rocks at Leigh Woods, to shorten the overall span to 630ft.

Apart from this modification, Isambard was given a free hand to design the final product, and he came up with a blueprint for a 240ft-high, chain support towers, and an elaborate cast-iron ornamentation on the pillars. He called the project his ‘Egyptian thing’ because of its style, and it was to have sphinxes on top of each pillar, as per the pyramids.

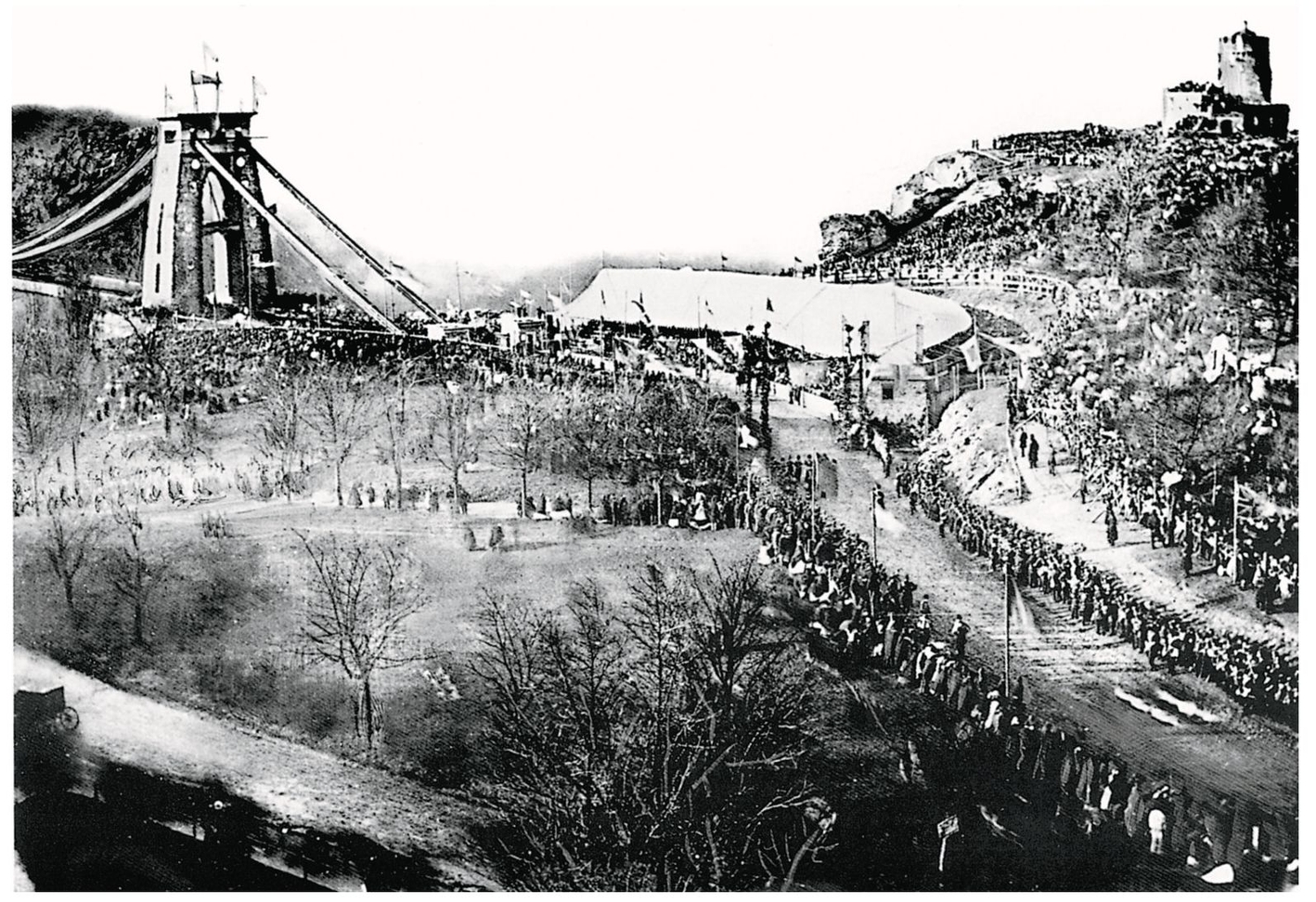

The celebrations at the opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge on 8 December 1864. ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS/BRUNEL 200

Crowds flock to the opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge. CLIFTON BRIDGE TRUST/BRUNEL 200

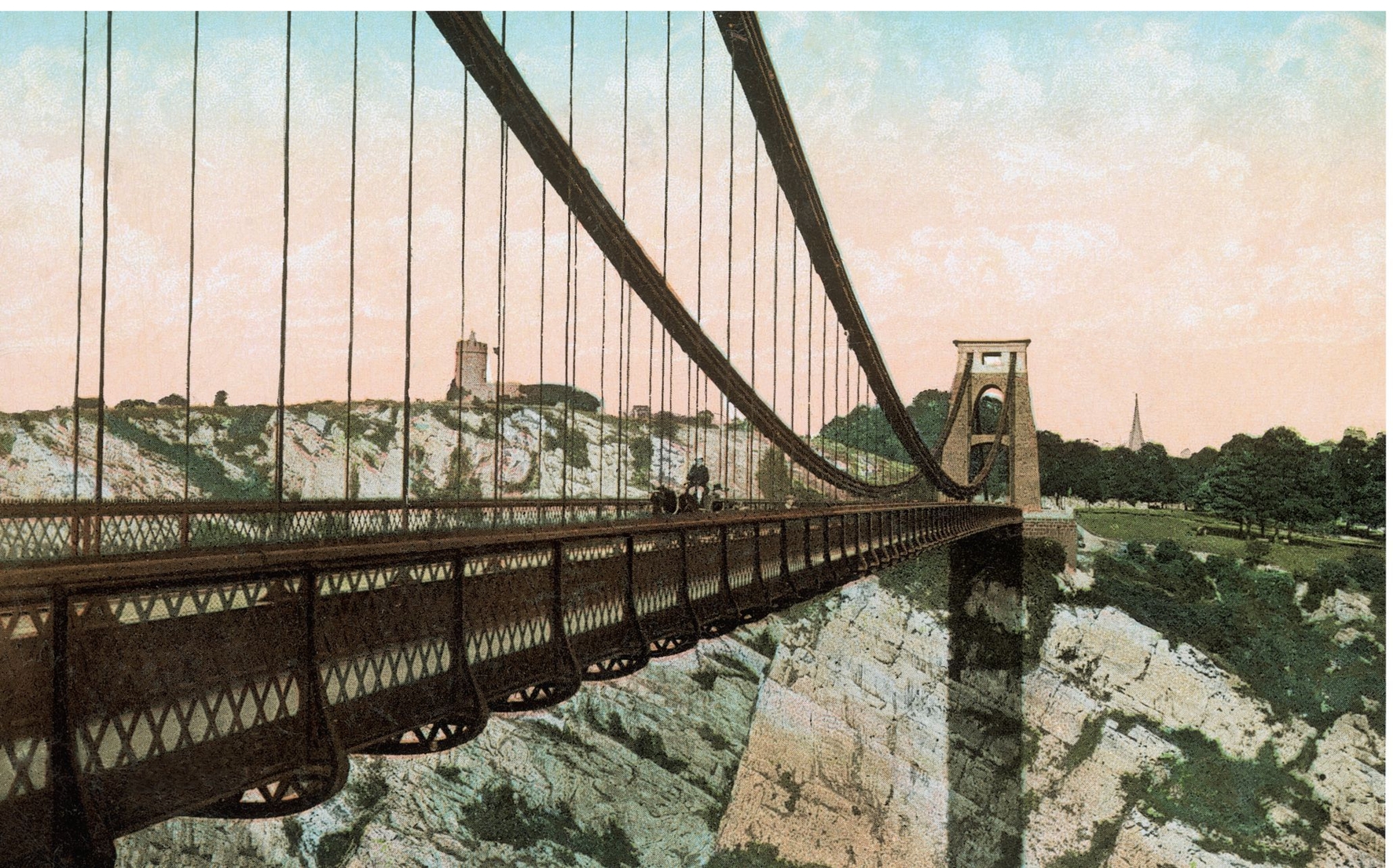

A hand-coloured, early-20th century postcard adds impact to Brunel’s design. ROBIN JONES COLLECTION

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a rare example of an instance where a man-made structure has enhanced its natural setting. ROBIN JONES COLLECTION

Isambard attended the launch ceremony for the suspension bridge on 21 June 1831 – only to be told shortly afterwards by the committee that they did not yet have enough funds to build it.

That year, he was caught up in Reform Bill riots in Bristol. The Bill aimed to widen the electorate, so that Members of Parliament would be seen to be elected, not just by a handful of powerful landowners but, by the public at large.

On 29 October, a stone-throwing mob stormed the Mansion House, official residence of the city mayor, in Queen’s Square, after the Conservative recorder of Bristol, Sir Charles Wetherell, who opposed the Bill, arrived for the assizes, along with a detachment of dragoon guards under Lt Col Brereton, who went on to side with the mob rather than charge against it.

The following day, Isambard and a friend, Nicholas Roch, were sworn in as special constables, after Brereton took his troops out of the city, and the Mansion House, Bishop’s Palace and toll houses were all looted and burned by the crowd. Isambard caught a looter, but he escaped.

A fortnight later, ever searching for an income, Isambard went to Wearside, where local merchants and businessmen gave him the job of designing a dock for Monkwearmouth.

His plans for what would become North Dock were at first rejected by Parliament, but the scheme went ahead in 1838, under the able supervision of Thames Tunnel bricklayer, Michael Lane.

However, the site chosen by Isambard’s clients proved difficult for navigation and the dock was little used. In recent times it has become a pleasure boat marina.

Returning south, Isambard visited the Stockton & Darlington Railway, which had become the first steam-hauled public railway in the world, when it opened in 1825. He had his first trip on a steam train on 5 December 1831 on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, the world’s first inter-city line, which had opened the year before.

Despite the nationwide publicity, which had been afforded to the Liverpool & Manchester, Isambard was not easily impressed, and his mind began working overtime with regard to the improvements he wanted to make to it. In his diary he wrote: “I record this specimen of the shaking on Manchester railway. The time is not far off when we shall be able to take our coffee and write, while going noiselessly and smoothly at 45mph – let me try.”

When the Reform Act was passed in 1832 and riots ended, confidence returned to both the country and Bristol. Money was made available for the improvement of the city’s Floating Harbour, which had been created by canal engineer, William Jessop, between 1804-10, by damming the River Avon, at Cumberland Basin and near Temple Meads, and diverting the Avon through a new channel to the south of the city centre.

Before, ships would be left high and dry in the city harbour because of the 30ft difference between high and low tide, Jessop’s pioneering scheme allowed ships to stay afloat, without risk of grounding on the muddy bottom of the river estuary.

The Floating Harbour had brought prosperity to the city, and the Committee for Bristol Docks – of which Roch was a member – sought further improvements to the artificial navigation.

In 1832, Roch brought in Isambard, who advised on the installation of sluices and an underfall dam at Rownham, for regulating water inflow and scouring silt.

In 1843, Isambard also came up with a steam-powered drag boat, Bertha, to move silt from the dock walls and she remained in service until 1968.

He also designed a new, south-entrance lock, completed in 1849, which used the first-ever wrought-iron buoyant gate.

Isambard’s work in Bristol greatly raised his standing in the port, and as we shall see, opened the door for arguably some of his greatest triumphs.

Eventually, more funds were raised for the Clifton bridge project, and the Marquess of Northampton, president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, laid the foundation stone on 27 August 1836.

Isambard Brunel designed this wrought iron, tubular, swing bridge to span the entrance to his South Lock, on Bristol’s Floating Harbour. Superseded in the 1960s by the electrically operated Plimsoll Bridge, which carries the A38 above the river, with the old bridge preserved beneath it. Brunel was a pioneer of tubular bridge construction, as evident in the later Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash. ROBIN JONES

As work began, a one-and-a-half-inch thick, 1000ft-long iron bar was laid across the gorge to allow both materials and men to be moved from one pier to the other. On the first occasion it was being manoeuvred into position, the capstan used to wind it over the great gap failed, and the bar plunged into the river below, becoming entangled with a passing ship.

To everyone’s surprise, Isambard insisted that despite this calamity, he would ride in the next basket to cross the wire from one bank to another. Everyone watching was mortified when the basket became stuck in the middle of the bar.

With certain death awaiting in the yawning chasm below, Isambard swung himself up from the basket to the bar and freed it.

Was his act of derring-do, sheer courage, or the best form of self-advertisement that he could ever have wished for?

Brunel’s South Lock was taken out of use in 1879 when a larger one was built to the north. Incidentally, the B Bond warehouse in the distance is now home to the Create Centre, an interactive attraction based on environmental excellence and run by the city council. ROBIN JONES

Nonetheless, locals paid to be hauled across the gap by the bar when work was not in progress.

However, financial problems continued to haunt the scheme, with the main contractor going bankrupt in 1837, leaving the bridge trustees to run the project by themselves.

It seemed in 1843 that the bridge was all but complete, but a glance at the accounts revealed that on top of the £45,000 spent to date, an extra £30,000 was needed.

After another decade of struggling to pay off debts, the trustees were left in 1853 with no option but to sell off the fixtures and fittings, leaving the unfinished piers on either side of the gorge.

The chains went to another Brunel project, the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash, but more of that later.

A modern-day view of the Wear estuary, with Brunel’s North Dock in the top left. It was bought by George Hudson’s York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway in 1846, and later became part of the North Eastern Railway. Brunel designed a suspension bridge to span the Wear to carry coal from the south side, but it was never built. North Dock was eclipsed by Sunderland South Docks, when they opened in 1850. SUNDERLAND COUNCIL

An offer in 1857 to finish the Clifton project on the cheap, by using ropes instead of chains, was met with scorn by Isambard, and there was serious talk of demolishing the piers and abandoning the scheme altogether.

Isambard would never see his magnificent bridge finished, but a year after his death in 1859, the Institute of Civil Engineers decided to complete the bridge as a monument to the man who by then had become acclaimed as one of the greatest engineers of all time.

After receiving parliamentary approval in 1861, and with £35,000 capital, a new company was formed, appointing renowned engineers William Barlow and John Hawkshaw to do the job, but on a simpler scale than that envisaged by Isambard.

Isambard had designed a suspension footbridge, the Hungerford Bridge, in London in 1842. It was replaced 20 years later to make way for the Charing Cross railway bridge – and the Hungerford Bridge chains, of similar design to those proposed for the Clifton bridge, were eagerly snapped up and given a new lease of life in Bristol. Barlow and Hawkshaw modified Isambard’s scheme, using three chains instead of two, and widened the roadway from 24ft to 30ft.

In June 1863, a temporary bridge was strung between the two towers, a hugely symbolic achievement in itself.

The last part of the permanent Baltic timber roadway was fixed into position in July 1864, followed by rigorous testing, which saw the bridge carry a spread load of 500 tons of stone, with estimates indicating that it would only fall down if 28,000 tons were laid on it.

Around 150,000 people turned out for the grand opening of the suspension bridge on 8 December 1864, when a huge procession from the city centre, accompanied by the army and 16 bands, marched to the Clifton, where triumphal arches had been erected.

The modified structure as completed is still a definitive showcase of Isambard’s vision and talent. Perhaps more importantly, the fact that it was finished posthumously is also a monument to the esteem in which his peers held him, and the strong bonds that he continually forged with Bristol itself.