Chapter 5

A HEAD FOR STEAM

God’s Wonderful Railway

Nobody knows for certain who built the first railways. Historians have traced the concept back to ancient Greece, where theatres in Sparta and Megalopolis had mobile buildings used occasionally for performances but which could also be rolled on and off the stage with their wheels following rows of channelled stone rails.

Later a Diolkos, or ‘railed way’, was built across the 3.7mile-wide Isthmus of Corinth for the long-distance transfer of goods, avoiding the need for a dangerous sea journey around the Peloponnese. Greek historians list eight occasions between 428BC and 30BC when it was used to transport ships across the Isthmus, while the Roman writer Pliny mentioned it carrying wagons.

There is some evidence that the Romans used a very basic form of railway in mines, while horse-drawn systems were certainly in use for industry in Europe by the late Middle Ages.

It is often assumed that railways superseded canals. The reality is that that many horse-drawn tramways in Britain were designed to serve the expanding inland waterways network, which made the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century possible. These tramways took goods to and from the nearest wharf, in cases where it was not practical or affordable to extend the canal.

As already stated, Richard Trevithick, who staged the world’s first public demonstration of a steam railway locomotive in 1804, did not foresee the time when the concept would form the basis of a national network of lines linking city to city.

However, while canals and turnpike roads greatly improved transport in many parts of Britain, they were still not capable of satisfying the increasing demands of heavy industry.

The products of the Industrial Revolution – iron and steel in vast quantities, steam-power technology and mass production – made the railway network possible.

A colour postcard of a Great Western Railway broad-gauge train hauled at speed by a Rover class locomotive. BROAD GAUGE SOCIETY

The Middleton Railway in Leeds – a heritage line since 1960 – claims to be the world’s oldest railway in continuous operation, as it has run ever since it opened in 1758.

In 1801, the Surrey Iron Railway became the first public railway in Britain to be authorised by an Act of Parliament, while the Carmarthenshire Railway at Llanelli, was the second one to be approved. However, despite popular misconceptions to the contrary, it is believed that the Carmarthenshire concern ran trains first.

As previously stated, the Stockton & Darlington Railway became the first public line in the world to be partly operated by steam, when it opened in 1825.

At the time, there was still much debate among early railway promoters as to whether the locomotive was the right way to go: some opted for horse traction, others said cable-hauled trains powered by stationary steam engines would be better.

It was all still very much in the melting pot 25 years after Trevithick’s engine successfully ran at Penydarren, the future of railways – if indeed they had one – was still shrouded in uncertainty.

In that year, the directors of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway held the Rainhill Trials in a bid to determine the traction issue, inviting inventors to demonstrate a locomotive that would be better than those available.

History records that George Stephenson’s Rocket beat Timothy Hackworth’s, Sans Pareil, and John Braithwaite and John Ericsson’s, Novelty to take the £500 prize, and earn the winner a deal to supply locomotive for the line.

The success of the Liverpool & Manchester renewed public interest in trunk railways, and Stephenson’s son Robert was appointed engineer-in-chief to build the 112-mile London & Birmingham Railway, which had been authorised in 1833.

City fathers around Britain stood up and took notice: they also wanted the benefits of a steam railway and its rapid connection to the capital.

Dr John Anderson had drawn up the first plan for a railway from Bristol to London in 1800, when only horse traction would have been available. Twenty-four years later, John Louden McAdam, the road builder, promoted the London & Bristol Railroad Company, which would have run through Mangotsfield, Wootton Bassett, Wantage and Wallingford, but with a terminus at Brentford, however this scheme quickly fizzled out.

The opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway had a resounding impact nationally, as it proved that steam engines could transport goods and passengers over long distances, in a relatively short space of time. Accordingly, in 1832, two further proposals for a London-Bristol railway were issued, but both failed to raise sufficient capital.

Beamish – the North of England Open Air Museum, in County Durham, is a world-leader in terms of research into early steam railways, including the handful that would have been operational during Isambard Brunel’s childhood. The museum’s replica of a long-lost locomotive type, the six-wheeled ‘Steam Elephant’, the prototype of which ran at Wallsend Colliery after it was built in 1815, hauls a train comprising wagons typical of the period. BEAMISH MUSEUM

However, in autumn that year, four Bristol businessmen, John and William Harford, Thomas Guppy and George Jones, agreed to pursue the idea and seek support from those with greater influence.

On 21 January 1833, a meeting was held between the Merchant Venturers, who had supported Isambard over the suspension bridge project, Bristol Corporation, the Bristol Dock Company, the Chamber of Commerce and the Bristol & Gloucestershire Railroad Company, to look at the prospect of building a line to London.

Agreement was reached to fund a survey of the route, and appointed none other than Isambard’s friend and colleague of the harbour improvement scheme, Nicholas Roch, now a member of the Bristol Docks Committee, to find an engineer for the job.

On 21 February 1833, Roch told Isambard about the project, and he along with several rivals were invited to survey a route. The winner would be chosen on the basis of whichever project would be cheapest.

Isambard was having none of it.

He told the railway committee that he would only survey a route that was the best, not the cheapest – and gambled with his reputation.

He won.

The committee confirmed his appointment, with WH Townsend as his assistant – a local engineer who had designed the horse-drawn Bristol & Gloucestershire Railway, which ran from coal mines at Coalpit Heath to the River Avon at Cuckold’s Mill.

The coat of arms of the Great Western Railway, which includes the shields of London and Bristol, above an entrance to Paddington station. ROBIN JONES

Isambard was given a month to survey the route and set out on horseback.

After he came up with a preferred line, estimated cost £2,800,000, the project was formally launched at the Bristol Guildhall on 30 July 1833, when it was decided that a company should be formed to build the line, with a general board of management, drawing directors from both Bristol and London.

Two committees were formed, one in each city, and their first joint meeting of the London & Bristol Railroad was held at the offices of Gibbs & Sons in Lime Street, in the City of London, on 22 August 1833.

When the prospectus was issued shortly afterwards, the name Great Western Railway appeared for the first time.

It was estimated that £3-million would be needed to build the line, but by October that year, only a quarter of it had been raised.

Nonetheless, on 7 September, Isambard was told to start work on the detailed survey, and set off again on his horse.

No railway would receive parliamentary sanction unless half its capital had been subscribed, and so on 23 October, the directors announced that they were to build two railways, one from London to Reading with a branch to Windsor, and the other from Bristol to Bath, in the meantime funds would be raised for them to be joined up at a later date.

The National Railway Museum’s replica of Stephenson’s Rocket and its Liverpool & Manchester Railway train. Although built primarily for the purpose of competing in, and winning, the Rainhill Trials of 1829, Rocket did not play a significant part in traffic on what was the world’s first inter-city railway. However, it is generally regarded as marking the watershed between early steam locomotives and ‘modern’ types, which would be used by Isambard Brunel on his Great Western Railway. ROBIN JONES

In March 1834, the Great Western Railway Bill was passed in the House of Commons by 182 votes to 92, but had then to go to committee stage.

The committee, chaired by Lord Granville Somerset, met on 16 April – and then sat for 57 days to discuss the bill.

Objectors had to be heard one by one. It was claimed that passengers would be “smothered in tunnels” and “necks would be broken,” and that the water supply for Windsor Castle would be destroyed. A farmer also expressed fears that his cattle would die if they passed under a railway bridge. The provost of Eton College claimed that the railway would be “dangerous to the morals of the pupils.”

Isambard took the witness stand for 11 days, and was praised for his patience and skill in answering questions under cross-examination. Ultimately, the committee approved the bill and returned it to the Commons.

It was, however, rejected by the House of Lords on 25 July 1834, by 47 votes to 30 – but by then, the scheme had engendered so much public support that victory for the objectors would be short lived.

The company issued a new prospectus in September 1834, this time for a complete trunk railway running via Bath, Chippenham, Wootton Bassett, Swindon, Wantage, Reading, Maidenhead and Slough, to be built for £2,500,000.

The 116-mile route had the distinct advantage over the shorter and more direct alternative between Bradford-on-Avon, Hungerford and Devizes, because it offered access to Oxford, Cheltenham and the Gloucestershire wool trade, with the growing industrial area of the South Wales coalfield just an extension away.

Company secretary Charles Saunders pulled out all the stops to raise the capital, and announced at the end of February 1835 than £2-million had been raised.

Again, the bill was approved by the Commons and went to committee stage, where it was debated for just 40 days this time, facing opposition from the London & Southampton Railway, which proposed a more direct line to Bath.

The committee returned the bill to the Commons after making a series of concessions, including the proviso that the route should be built no nearer to Eton College than three miles.

The bill received royal assent on 31 August 1835 – and work began within a month.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s greatest hour had come.

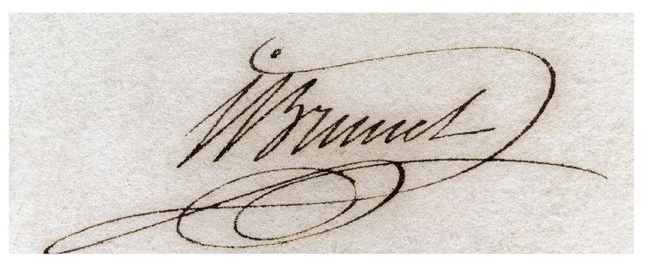

Isambard Brunel’s signature.