Chapter 7

THE RAILWAY ADVENTURE BEGINS

Paddington to Swindon

The building of the Great Western Railway began in 1836, the same year that Isambard Brunel married Mary Horsley, sister of accomplished painter John Callcott Horsley, a member of the Royal Academy, who was later to paint his portrait on several occasions.

The wedding took place on 5 July in Kensington church, followed by a honeymoon in North Wales and the West Country, with GWR company secretary, Charles Saunders, meeting him midway through the trip at Cheltenham, to bring him up to speed on the building of the line.

The couple moved into their stylish home at 18 Duke Street between Piccadilly and Pall Mall (now covered by the Colonial Office), which he had been able to afford on his £2000-a-year salary from the GWR.

They eventually had three children, including one, Henry Marc, who also became an engineer and worked on Tower Bridge, with Beauchamp Tower, inventor of the spherical engine – crossing the Thames in the air while his grandfather had burrowed beneath it.

Isambard’s appointment as engineer to the GWR, together with other high-profile projects had finally given him an income on which he felt he could sustain a family; indeed, after work began on the line at both ends, shortly after its enabling act was passed, he rarely had cause to look back in financial terms.

The eventual terminus chosen for the GWR was at a village called Paddington, then a rural location on the outskirts of the city of London.

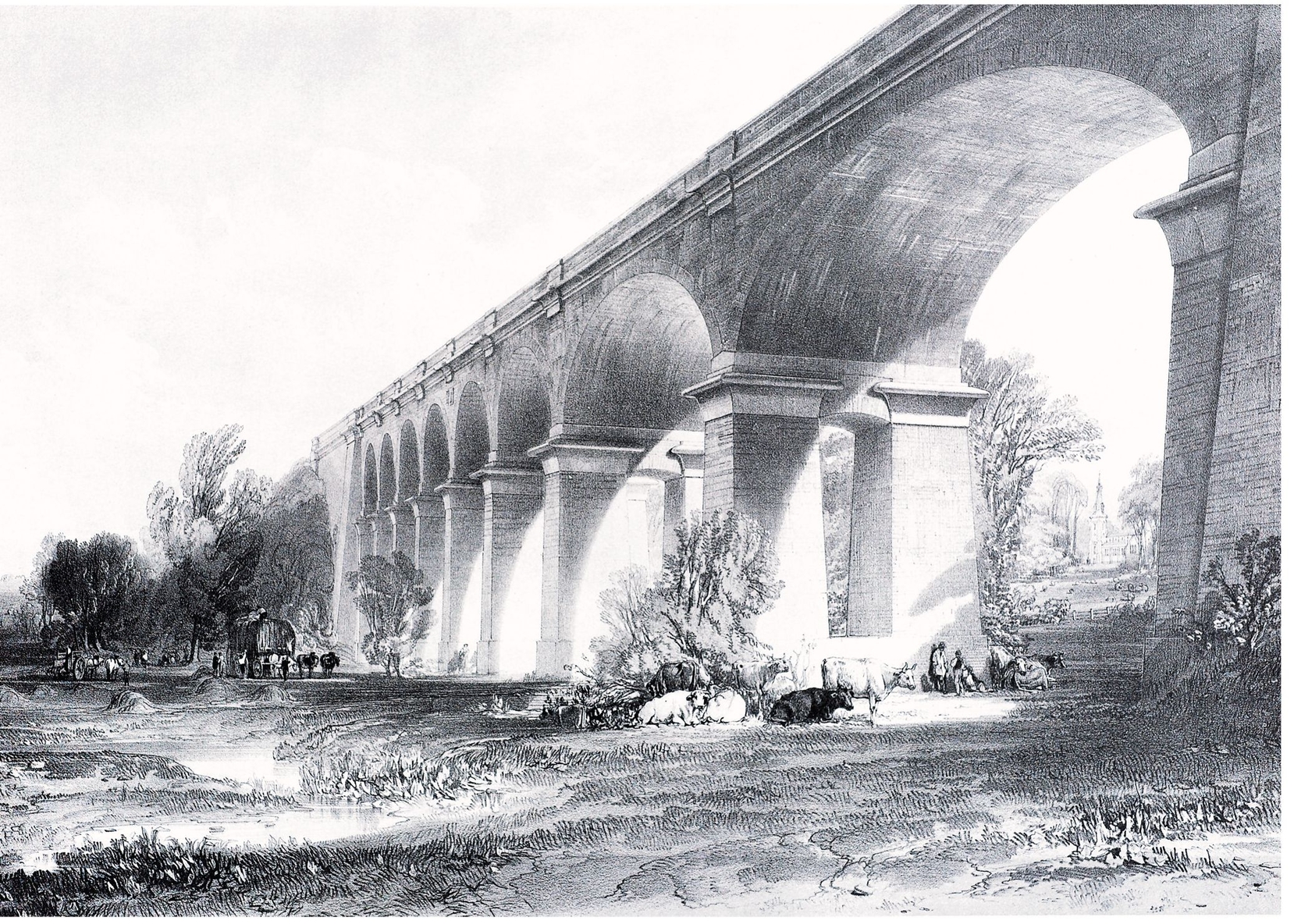

The first contract for the construction of the line had been let in September 1835 for the building of a stupendous 891ft-long viaduct at Hanwell, across the River Brent in London, comprising eight brick arches with a span of 70ft, the highest being 65ft.

Architect, printer and publisher Charles Cheffins commissioned artist JC Bourne to produce a series of drawings of the Great Western Railway. These were printed in The History and Description of the Great Western Railway, published by David Bogue in 1846, and the best depiction of Isambard’s pioneering line in its infancy. Wharncliffe Viaduct at Hanwell, was the first major engineering feature on the GWR line from Paddington. ROBIN JONES

Wharncliffe Viaduct today. ROBIN JONES

It was named after Lord Wharncliffe, who had helped the GWR bill through the Lords, and it still carries his coat-of-arms today. Originally the viaduct carried two broad gauge tracks, but it was widened in 1890, the extra north pier matching Isambard’s original two, and today carries four tracks.

Again, Isambard opted for an Egyptian style for the structure, as with his original Clifton Suspension Bridge plan, mirroring the contemporary trend towards neo-classical architecture.

Indeed, Brunel structures seem designed to appear as if the Romans had never left Britain in 410 AD and had finally laid railways between their temples, villas and amphitheatres in a new golden age.

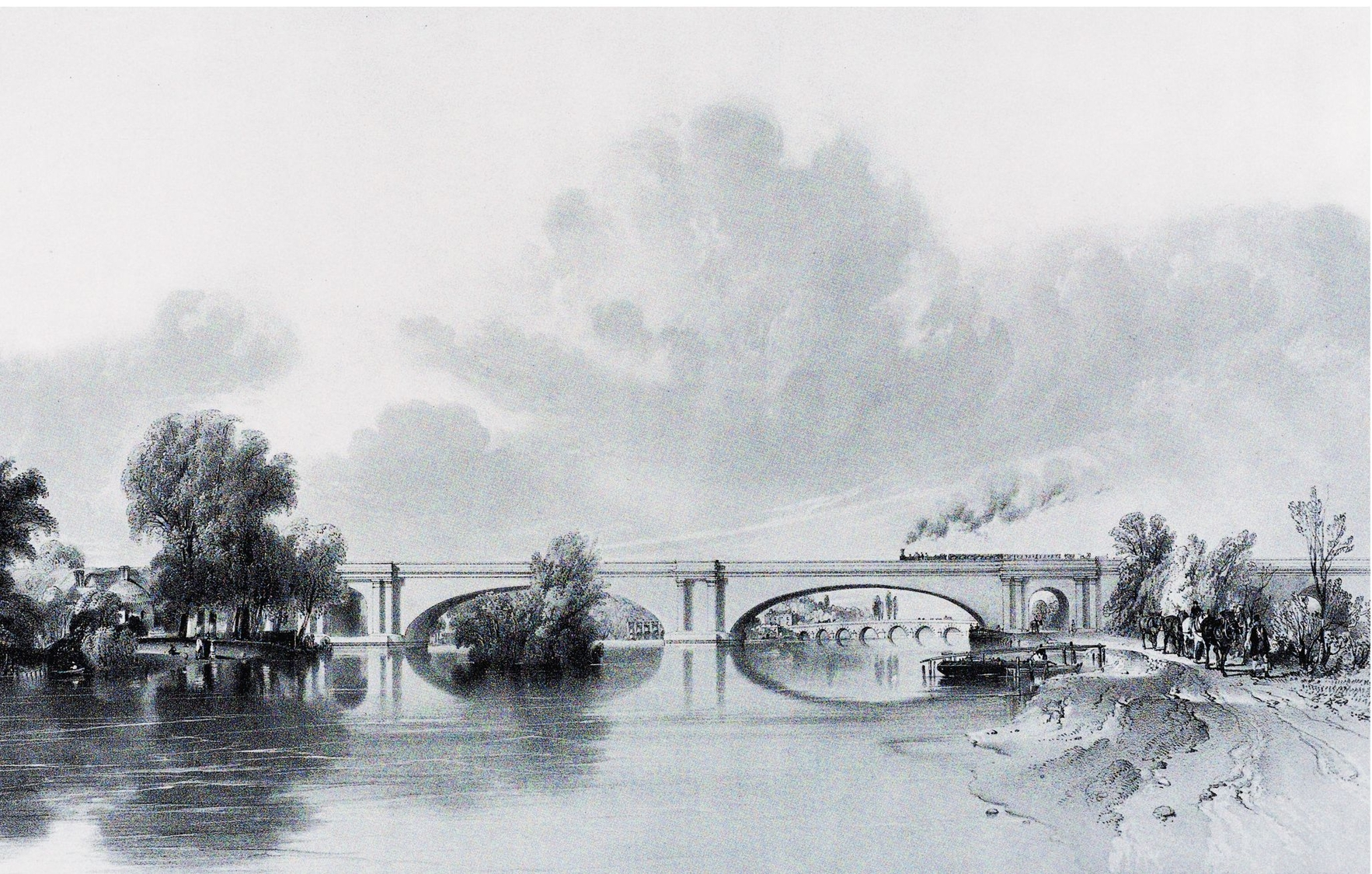

Daubed with graffiti today, the viaduct nonetheless remains one of the real treasures of the borough of Ealing. However, it was easily eclipsed in magnificence by the semi-elliptical twin-span bridge across the Thames at Maidenhead, which remains one of Isambard’s finest achievements.

Here, Isambard had been faced with crossing a river, which was a navigable channel and 100ft wide. The river commissioners stoutly refused any obstruction, so Isambard had to design a bridge with only one support in the middle, so it would allow clearance for the barges – whose trade was soon to be killed off by the GWR.

In turn, Isambard refused to raise the level of the railway and interrupt the super-smooth 1-in-1320 ruling gradient between London and Didcot.

Drawing on experience gained in the building of the Thames Tunnel, he came up with a rule-stretching design that had never been attempted before, in order to tackle this extreme wideness.

Critics insisted that the bridge, the largest brick feature on the London-Bristol line, would never stand up. We are still waiting for them to be proved right.

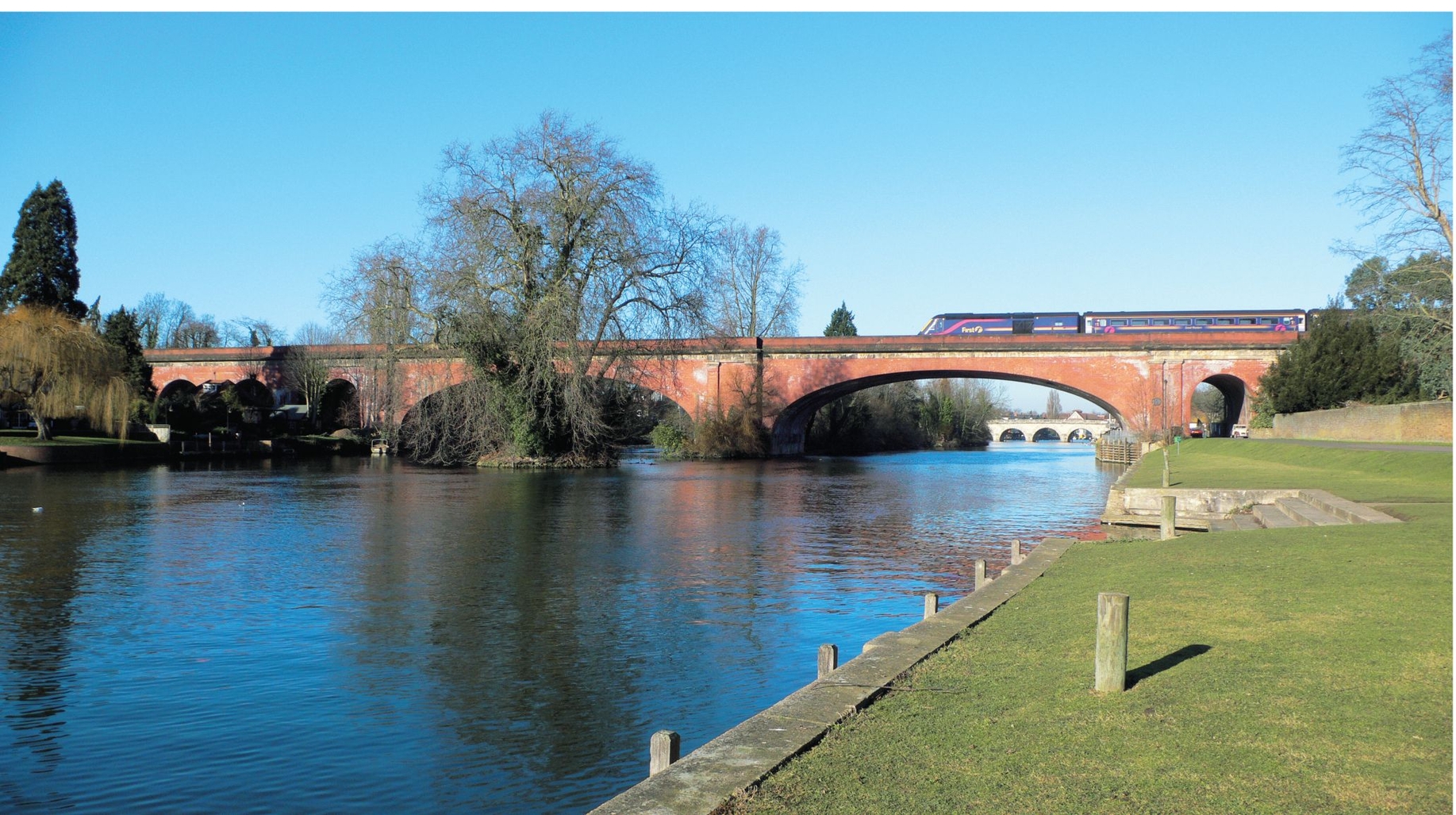

The bridge too was widened in the 1890s, again to Isambard’s design. Isambard later admitted that had it been built 20 years later, he would have used cast iron or timber; had he done so, Maidenhead would have been aesthetically so much poorer and Victorian bridge technology that much more limited.

Despite the fact that Isambard was at the forefront of bridge-building technology and had placed himself at its cutting edge, during the early years of the building of the railway, heavy criticism arose about the questionable state of the track as well as poor locomotive performance.

Isambard found himself having to defend his choice of 7ft 0¼in gauge to hostile shareholders. He survived the criticism, and was allowed to carry on his work.

Nevertheless, it had become clear that while engineer extraordinaire Isambard had dabbled with locomotive design like the Gaz Engine project, there were many who knew much more about steam railway engines.

While the first stages of the railway were being built, Isambard had ordered a motley collection of 19 locomotives from various builders across the country, after giving them the most basic specifications to follow and allowing them to design and produce the rest.

The magnificent Maidenhead Bridge, the one they said would never stand up, as drawn by JC Bourne. BRUNEL 200

Isambard Brunel’s Maidenhead Bridge easily takes today’s high-speed trains. ROBIN JONES

The end results as delivered, were at best patchy in performance, but Isambard realised that his railway career would depend on their success.

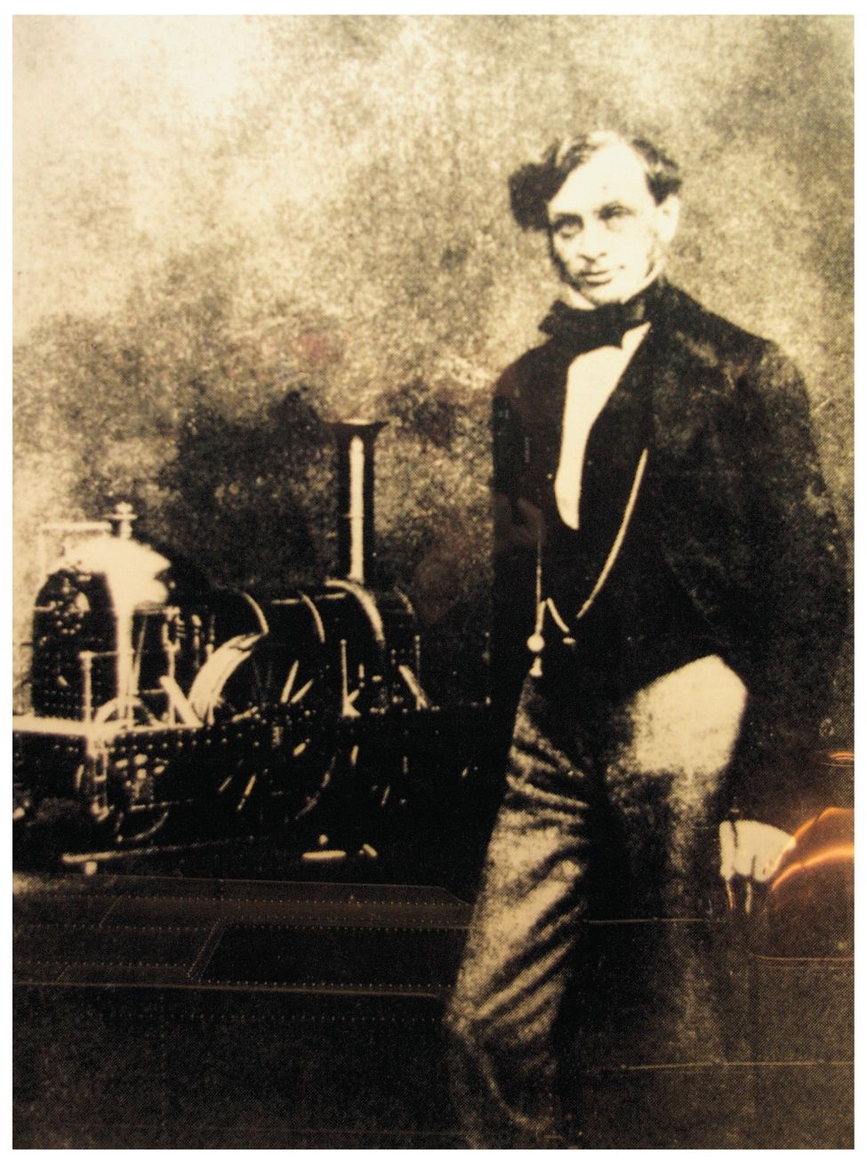

A shining knight had already appeared in the summer 1837, in the form of 20-year-old Daniel Gooch, who had written to Isambard about the position of locomotive engineer on the GWR.

We’ve all heard about cases in tabloid newspapers when a 16-year-old fan applies for the managerial vacancy at a Premiership football club and is sportingly given a guided tour of the ground, and a chance to meet the players, purely for publicity, but of course his application is taken no further.

However, in this case, Gooch had rather more substance to him. When he made his application, he had already worked at Robert Stephenson’s Vulcan Foundry in Newton-le-Willows and helped his brother, TL Gooch, survey the London & Birmingham and Manchester & Leeds railways, with a brief spell of unsuccessful engine-building in Gateshead along the way.

Despite Gooch’s tender years, Isambard was so impressed after travelling north to interview him, that he followed his instincts, and gave him the job at £300 per year.

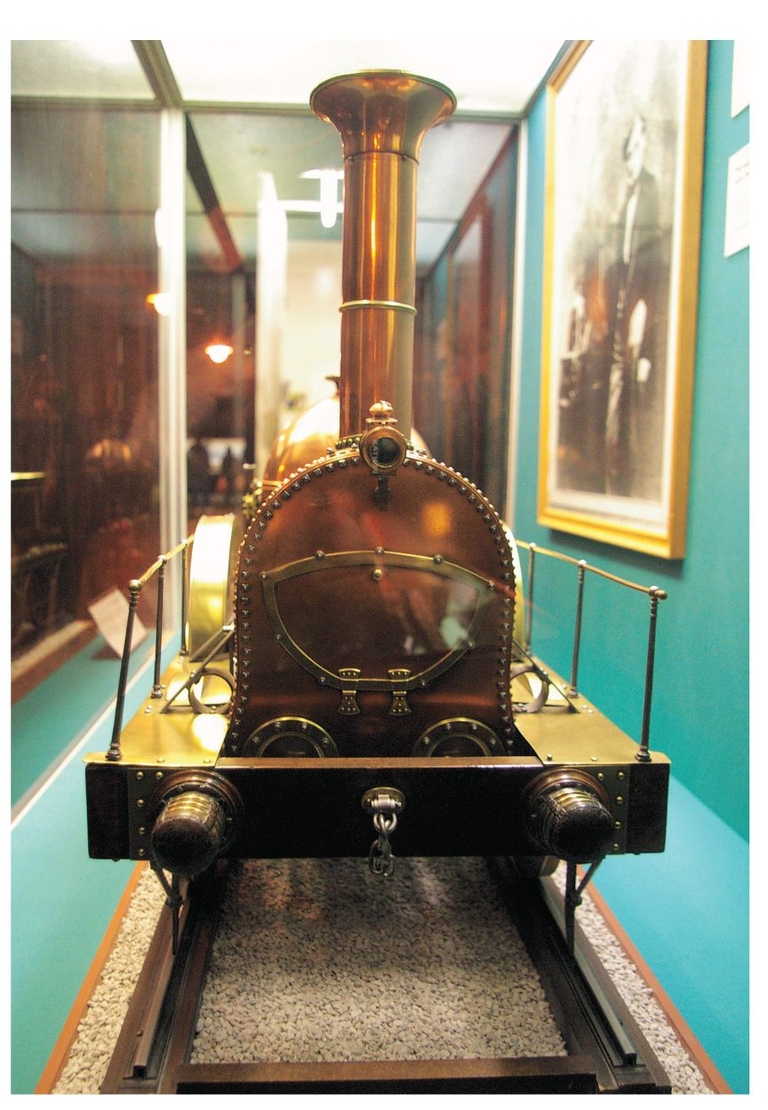

GWR locomotive engineer Daniel Gooch, pictured with a model 2-2-2 engine, which he commissioned from London craftsman John Clement in 1840.

This model, a rare surviving locomotive from the broad-gauge era, is now in the National Railway Museum at York. ROBIN JONES

“I was very young to be entrusted with the management of the locomotive department of so large a railway,” Gooch later said, “but I felt no fear.”

Gooch was entranced by the potential of broad gauge, but was horrified at the sight of some of those early locomotives delivered to the GWR on Isambard’s orders, including one built to an absurd design with a 10ft driving-wheel on a 2-2-2 leading truck, and with its boiler mounted on a trailing chassis behind.

While the line was still under construction however, Gooch had time to set up a locomotive building operation for the company and produced workable designs for its future.

In the meantime, after the initial length to Taplow had opened, it became clear that only six of the motley collection of engines ordered by Isambard were capable of running.

Saving the GWR’s bacon was none other than Robert Stephenson, who supplied a 2-2-2 locomotive, North Star, which had been built for the 5ft 6in-gauge New Orleans Railway before the order had been cancelled.

Regauged to 7ft 0¼in, North Star arrived at Maidenhead by barge at the end of November 1837 and waited there until track laying reached it in May 1838. Gooch claimed to have played a part in the design of North Star, which was so successful that a sister locomotive, Morning Star, soon followed. They were so successful that a further ten of the type were bought for the GWR.

This splendid pub sign, at a hostelry of the same name, near Cholsey, recalls Morning Star, the second of the Robert Stephenson locomotives, which made the early GWR a success. ROBIN JONES

The London to Maidenhead section opened to paying passengers on 4 June 1838, although a directors’ special had been run five days before, hauled by North Star, when a banquet for 300 guests was held in a tent at Maidenhead. The initial Maidenhead terminus was a mile short of the town, at the village of Taplow.

By 1839, the passenger service was extended over Maidenhead Bridge to Twyford, and the GWR board ordered Gooch to design and buy locomotives capable of handling this longer run.

He modified the Stars by introducing the large haystack-style firebox, so typical of broad-gauge engines, along with outside sandwich frames, a domeless boiler covered in wooden planks and inside cylinders. And so Fire Fly, the first of 62 hugely successful 2-2-2 locomotives of the Firefly class, was delivered, quickly relegating the engines ordered by Brunel to the scrapheap.

The GWR had great cause to thank the young upstart and never looked back.

It was the start of a great partnership between Isambard and Gooch, who was by no means a ‘yes’ man. He would not hesitate to criticise his superior, if he thought it appropriate, even to the GWR board itself, while always holding Isambard in great respect.

The next big obstacle to building the line westwards presented itself in the form of a hill at Holme Park next to the village of Sonning, east of Reading.

At first Isambard planned a mile-long tunnel through it, but then agreements with landowners were reached so that it could be opened out into a cutting, as the GWR board feared that passengers might have been deterred from travelling for so long in the dark.

Sonning cutting was built because the GWR directors were concerned that passengers might be scared in the dark in a mile-long tunnel. FRED KERR

The monstrous Sonning cutting, one of the biggest excavations of the early railway age, nearly two miles long and up to 60ft deep, took a team of 1200 navvies, aided by 200 horses, to dig out during the summer of 1838.

Not only that, but a court case had been brought against Isambard by a contractor who had been appointed to do several contracts near Bristol. It took 16 years before final judgement was given.

Storms that winter caused horrendous delays to the work at Sonning, and it was not until the end of 1839 that the cutting was completed, complete with a brick three-arch bridge to carry the main London-Reading road across it, along with a smaller timber bridge that many believe was the basis for the great trestle viaducts that Isambard would build in Devon and Cornwall in the coming years.

Laying broad-gauge track took longer than a conventional railway with sleepers, and so the completion of the GWR exceeded the original completion date. The 30ft ‘baulks’ laid between each cross-member or ‘transom’ at 15ft intervals and packed with ballast to form a firm foundation for the base, required far more labour and raw materials, not least of all the need to treat the pine to prevent rot.

Needless to say, this system of laying track, nicknamed the ‘baulk road’, and its design, was not adopted elsewhere in Britain.

On 14 March 1840, a special directors’ train was run from Paddington to Reading – hauled by Fire Fly – and the first public services followed on 30 March, as the company needed to begin earning money without delay.

Reading and Slough were both built as ‘one-sided’ stations by Isambard, his logic being that the entrance and booking hall should be on the side of the railway where the town lay, so that the public should not have to cross the tracks.

The eastbound (or up) and westbound (down) platforms were arranged so that they would be on the same side, and each accessed by loops off the mainline. There was much criticism of the amount of crossovers that the trains had to make to leave the mainline and enter the loops to pick up or set down passengers, but in those days of comparatively spare traffic, it worked well. Isambard was later to effect the same arrangements at other stations including Taunton, Gloucester, Newton Abbot and Exeter.

As traffic increased and the railway was updated, these one-siders were replaced with conventional stations; Reading was the last to be converted, in 1899.

The section from Reading to Steventon on the Oxford turnpike road, opened on 1 June 1840, allowing a coach connection to the city 10 miles away, until it was superseded by a station at Didcot in 1844 – a case of an early park-and-ride.

Near Steventon station, Isambard ordered a large Tudor house to be built for the line’s superintendent; it was also used as the directors’ offices and for their board meetings in the early years.

West of Reading, two more splendid Brunel Thames crossings can be seen, the sweeping brick arches of Basildon Bridge, west of Pangbourne and Moulsford Bridge, just before Cholsey.

Moulsford Bridge crosses the Thames between Reading and Didcot. ROBIN JONES

Furthermore, the short branch from Slough to Windsor includes the bowstring Brunel’s Bridge with its 203ft span. It is the oldest surviving example of one of Brunel’s wrought-iron bridges.

It was on 20 July 1840 that services extended to Faringdon Road, 63½ miles from Paddington, later renamed Challow. That remained the terminus for five months, and on 17 December 1840, services were extended to Hay Lane, a minor road crossing at the entrance to Studley cutting, four miles from Wootton Bassett. This temporary terminus was later officially named Wootton Bassett Road.

It was from this date that the GWR issued its first proper passenger timetable. Meanwhile, a sleepy little market town called Swindon three miles back up the line was about to be hauled on to the international stage by Brunel and, in particular, Gooch.

Isambard Brunel’s early wrought-iron bridge carrying his Windsor branch. ROBIN JONES