Chapter 9

BOX AND BEYOND

The GWR Line from Swindon to Bath

When the going gets tough, the tough get going. That modern phrase might accurately sum up the predicament facing Isambard as he prepared to complete the western section of the GWR line from London to Bristol.

The first half from Paddington to Swindon has often been nicknamed Brunel’s billiard table because of its gentle ruling gradient of 1 in 1320.

However, the remainder to Bristol, running over the hilly terrain of the southern Cotswolds, presented Isambard with his greatest challenge to date.

Work on building the west section of Swindon began in 1837 and from Wootton Bassett; where a huge incline was created, major earthworks were required.

Herein lay the first problem encountered by Isambard. Constant rain during the wet winter of 1839 caused landslips at many of the embankments built from the spoil, which had been excavated from the cuttings built by his army of navvies.

It has been said that there is barely a length of line between Swindon and Bristol where the natural ground was used for the railway, meaning all of Isambard’s finest design skills were called into play.

However, his work at Chippenham is a joy to behold, and a must for anyone setting out on a Brunel trail. Next to the wonderful Grade II listed station booking office and entrance, stands an office building, restored by Chippenham Civic Society, and which is believed to have been Isambard’s office while he oversaw the building of this section of the route.

The biggest treasure in the town, however, lies in the valley to the south of the station. The 90-yard Cotswold-stone Chippenham Viaduct, otherwise known as the Western Arches is also Grade II listed, and looks very much the same as it did when it was built, despite work to widen it in the early 20th century. It is to be illuminated as part of the Brunel 200 celebrations.

The central span of the limestone Western Arches at Chippenham still look much the same as they did when they were built, although the town-centre side has been covered in brick. ROBIN JONES

Isambard Brunel’s drawing office next to Chippenham station. ROBIN JONES

The Cotswold-stone booking hall at Chippenham station. ROBIN JONES

Leaving Chippenham, the railway runs along an embankment for two miles, and then through a deep cutting leading to the biggest obstacle on the whole line, an outlier of the Cotswolds known as Box Hill, between Corsham and Box. This, the biggest stumbling block of them all, required Isambard to pull off the greatest engineering feat on the whole of the railway in order to pass by.

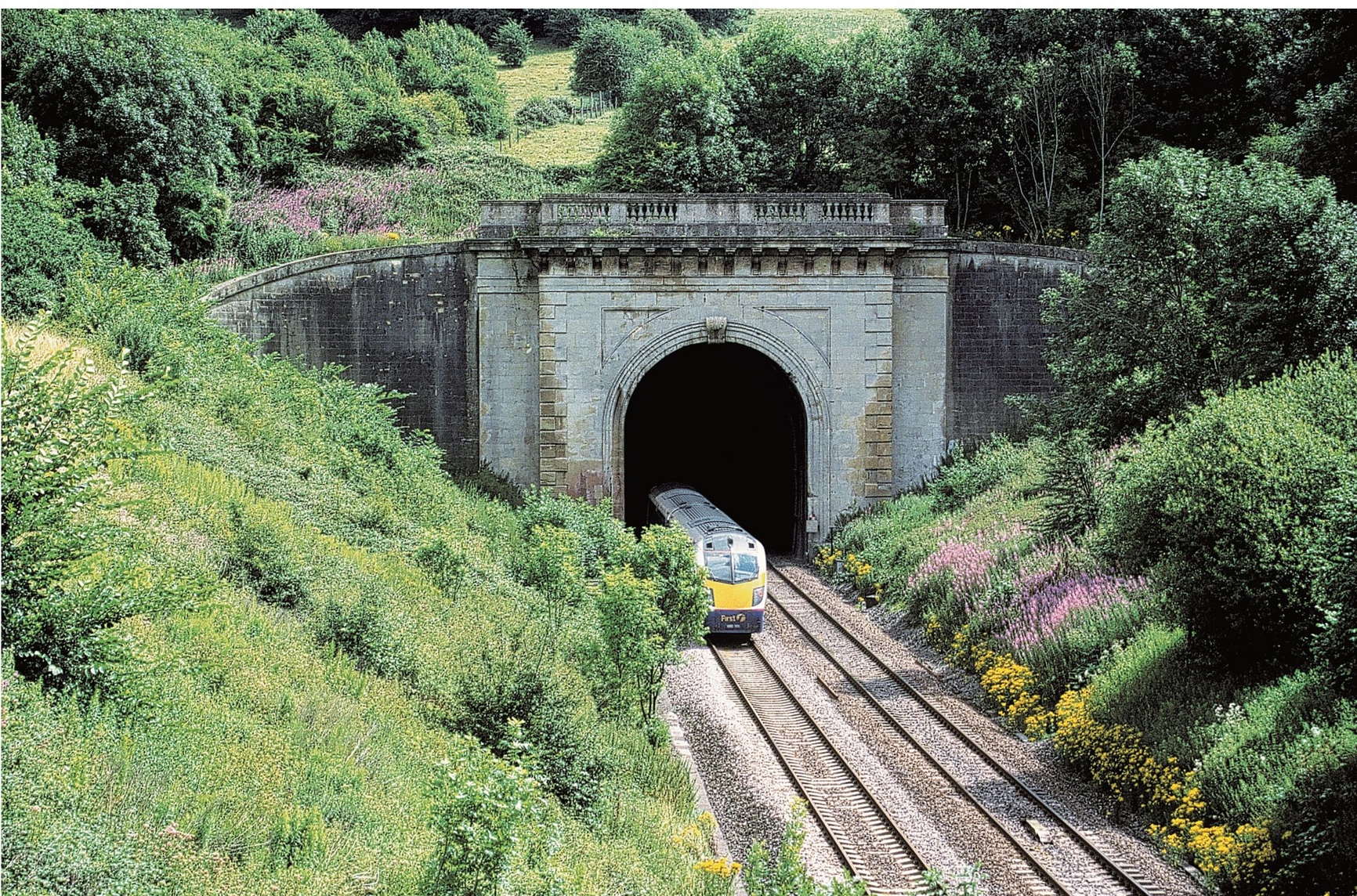

The fact that Box Tunnel remains in regular use today is a monument to Isambard Kingdom Brunel. ROBIN JONES

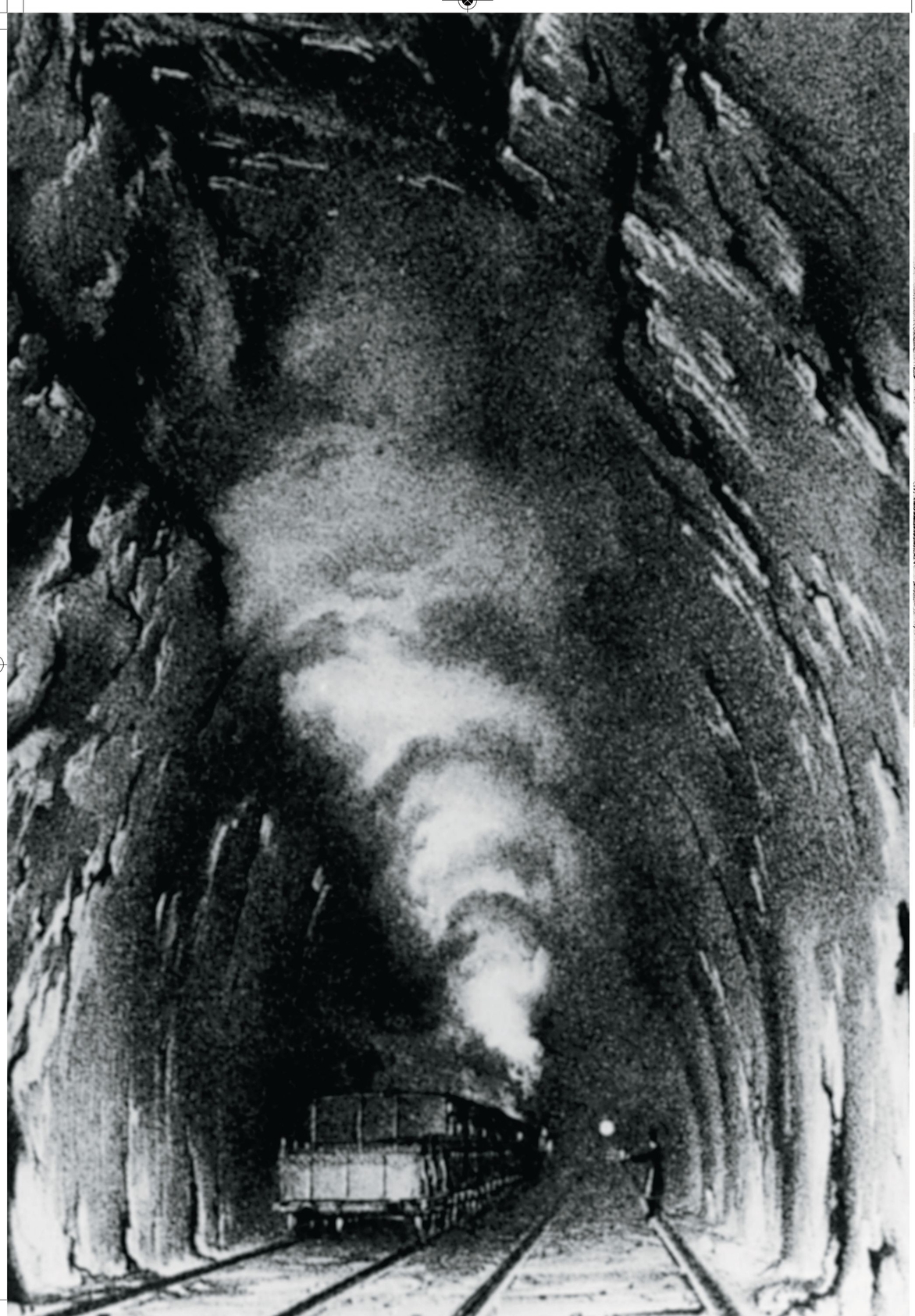

Left: The interior of Box Tunnel as illustrated by JC Bourne. Daniel Gooch once said that when one of the two tracks was open and workmen were completing the other one, the whole interior was lit from end to end by their candles. BRUNEL 200

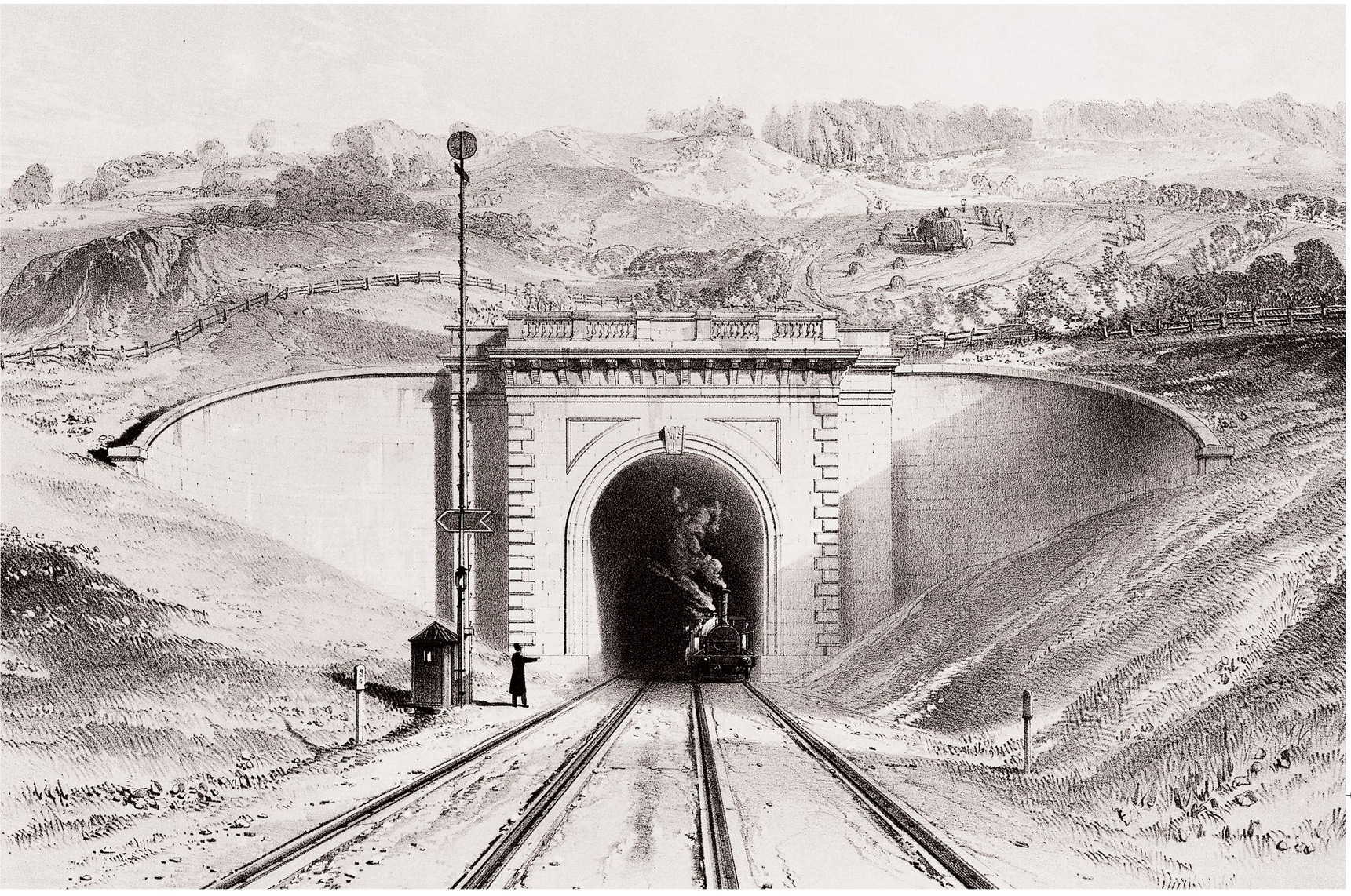

Box Tunnel, as sketched by JC Bourne in his famous album of illustrations of the GWR in 1846. BRUNEL 200

Box Tunnel became a legend in Isambard’s lifetime – and for evermore.

Many of Brunel’s contemporaries were aghast at his plans to build a tunnel nearly two miles long to take passenger trains.

Because there was a ruling 1-in-100 gradient, one MP had claimed that if its brakes failed, a train could run out of control through the pitch black, accelerating up to speeds of 120mph and suffocate all those on board in the process. Another argued during a debate in the House of Commons that if the tunnel were built, no one would be brave enough to enter it.

Unruffled in his belief that he knew far better as regards the future direction of transport engineering, Isambard and his resident engineer, William Glennie, began work on digging the tunnel in September 1836.

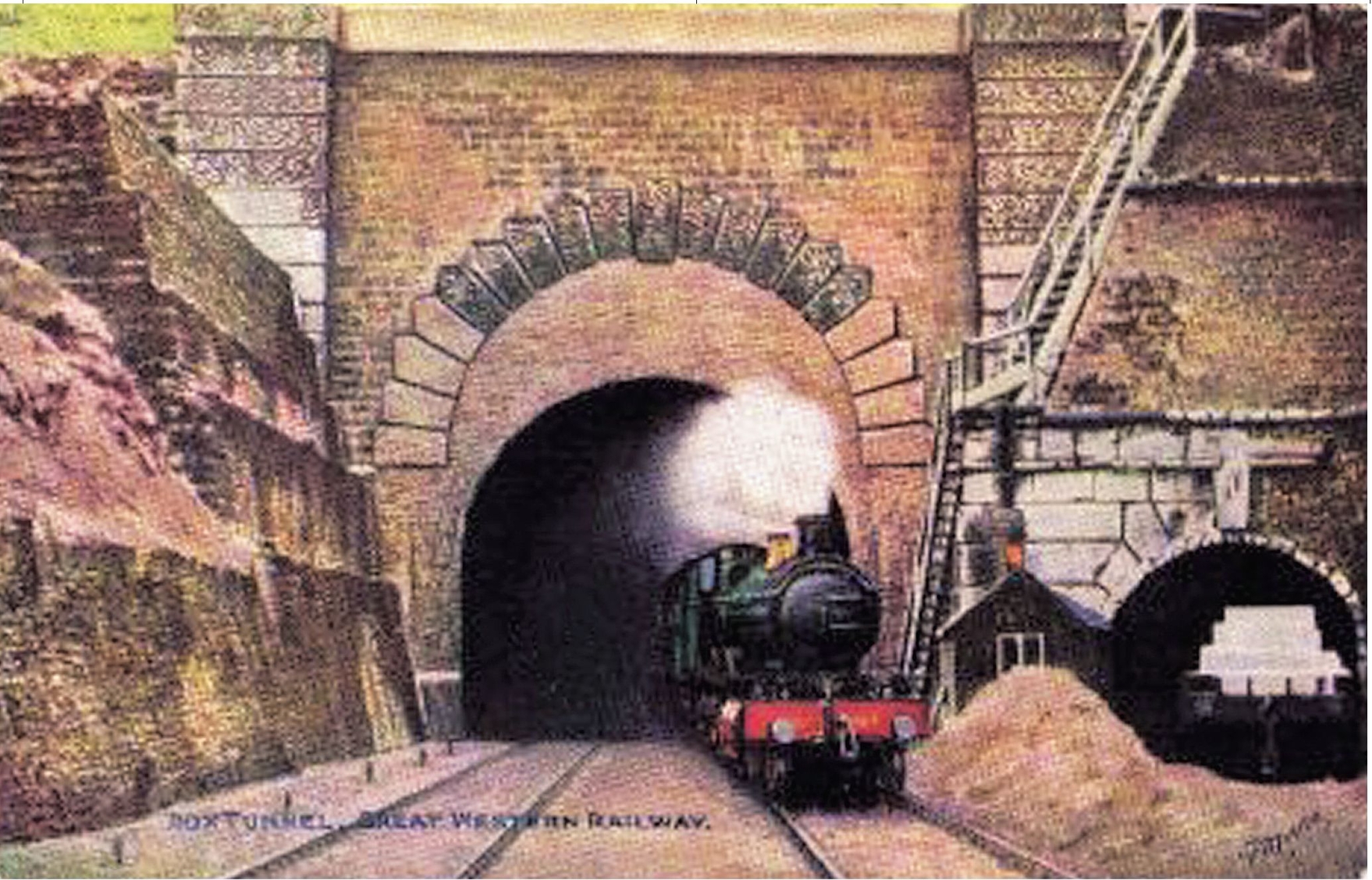

A hand-coloured postcard of the eastern end of Box Tunnel, as it looked in the early 20th century.

From the outset, as many as 1200 navvies were regularly engaged on the project, aided by a team of 100 horses to take away the spoil, which eventually totalled 247,000 cubic yards.

A ton each of gunpowder and candles was used each week during the tunnel’s five-year construction, during which time there were frequent delays caused by flooding, quicksand and layers of hard rock.

Work continued 24 hours a day, with labourers sharing beds in Box and Corsham; as one got out to go to work, another came home and took his place. As was the case with mass gatherings of navvies elsewhere in Britain – navvy being a term for a workmen who built a canal navigation using only a pick and shovel – there were frequent reports of drunkenness and disorder in the locality while the tunnel was being built.

It was estimated that accidents caused while working in the primitive conditions claimed the lives of up to 100 navvies, with many more maimed. In the final push for completion, 4000 workmen and 300 horses were engaged on the tunnel project.

Daylight was reached in early spring 1841, and the critics who claimed that the excavations from the two ends might never meet were silenced when the side walls lined up within an inch and a half.

The tunnel was completed on 30 June 1841 to the stage where one out of two tracks could be used by trains. Initially, some passengers chose to leave the train before the tunnel and rejoin it the other side, having journeyed round by road.

As the line had by then also been built from Bristol and Bath eastwards, the completion of the tunnel also marked that of the entire route.

Well beyond the predicted schedule, the tunnel was opened at last on 30 June 1841, completing the Great Western Railway main line.

At 9636ft, Box Tunnel was the longest on any railway in Britain, and Isambard spared no expense in adding his distinctive grandiose style, finishing the portals in Bath stone to a classical style, topped with a balustrade.

Despite Isambard’s boast to the contrary, it was not the longest tunnel in the country. That honour was held by the 11,451ft-long Sapperton Tunnel on the Thames & Severn Canal, finished 52 years before, but the fact that its roof has since fallen in, presenting a major hurdle to bids to achieve restoration of through navigation, while Box Tunnel is still in regular use today, weighs any argument about an ability to stand the test of time back in Isambard’s favour.

Box Tunnel remains as magnificent today as when it was built, with the First Great Western high-speed trains looking like OO-gauge Hornby models as they pass in and out.

As the railway entered Bath, there was another major hurdle to cross – the first purpose-built route between London and the Roman city, in the form of the Kennet & Avon Canal.

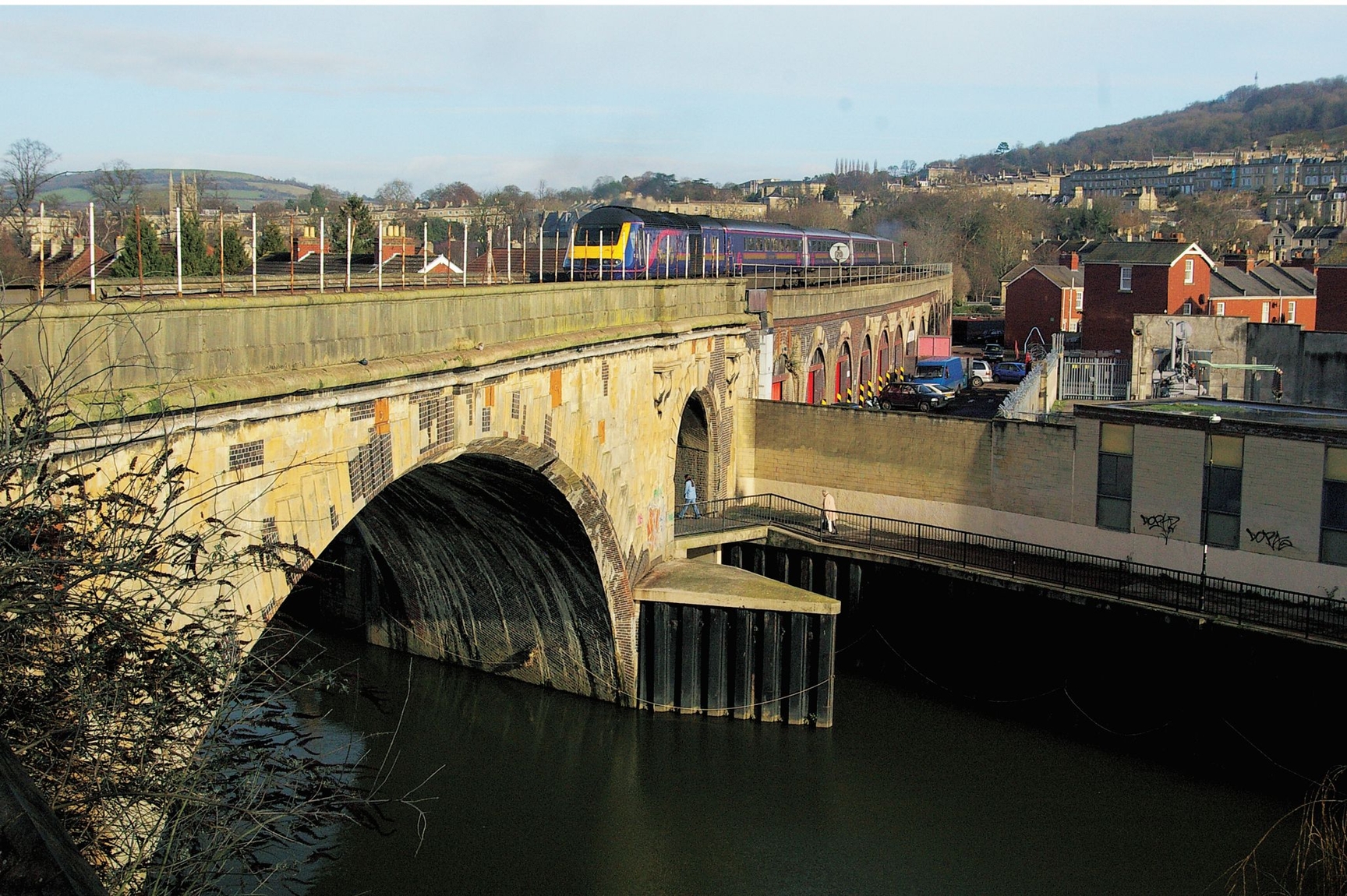

The arch of St James Bridge and viaduct over the Bristol Avon, looking eastwards, from Bath Spa station. Originally the bridge was faced with Bath stone, but it was largely refaced in brick during the 1920s. ROBIN JONES

Brunel’s retaining wall and ornamental bridges in Bath’s Sydney Gardens. ROBIN JONES

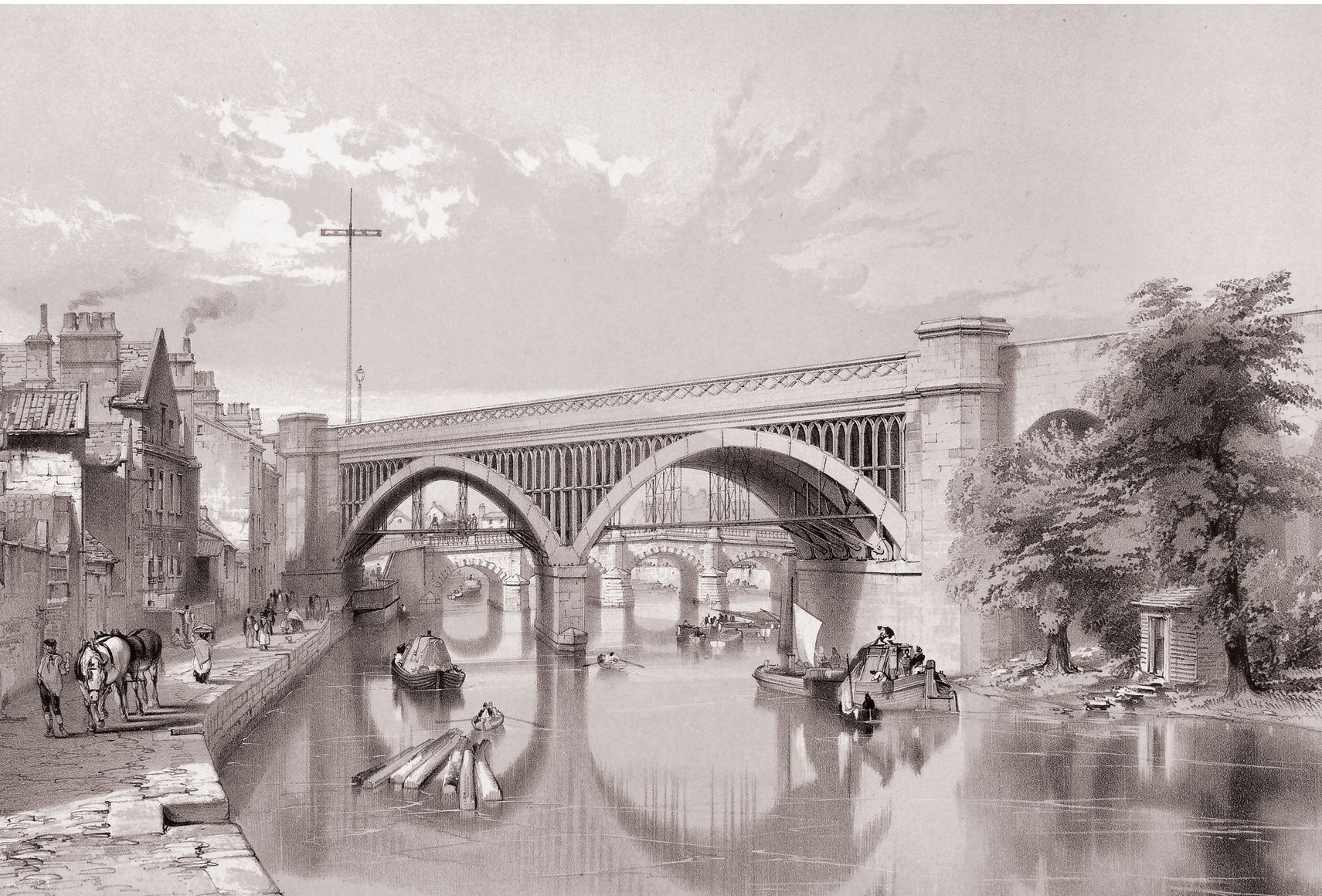

Brunel’s original skew bridge over the Avon, immediately west of Bath Spa station, long since replaced by a girder bridge. BRUNEL 200

A section of the canal at Sydney Gardens, a Bath pleasure park, needed to be diverted.

Isambard again ripped up the architect’s rule book, coming up with a 27ft-high retaining wall, 5ft thick in places, in order to create a barrier between his railway cutting and the canal.

Again, Isambard treated the infrastructure of his railway as if it was a work of art: how many engineers of his day, or even afterwards, managed to so successfully merge the two disciplines, even if he was spending other people’s money in the process?

Deliberately enhancing the appearance of the pleasure gardens, next to the retaining wall, he provided a stone and an ornamental cast-iron bridge to link the two parts of the park, which had been bisected by both railway and canal, and added a skewed stone bridge to carry Sydney Road – a much smaller task than Box Tunnel, but a masterpiece nonetheless.

Further major engineering work was needed as the railway passed through Regency Bath, where it is carried mainly on embankments and viaducts.

There had been much local opposition to the coming of the railway, and Brunel was called on to work overtime to solve the seemingly impossible puzzle of how his line could serve the city, without damaging the richness of its historic areas.

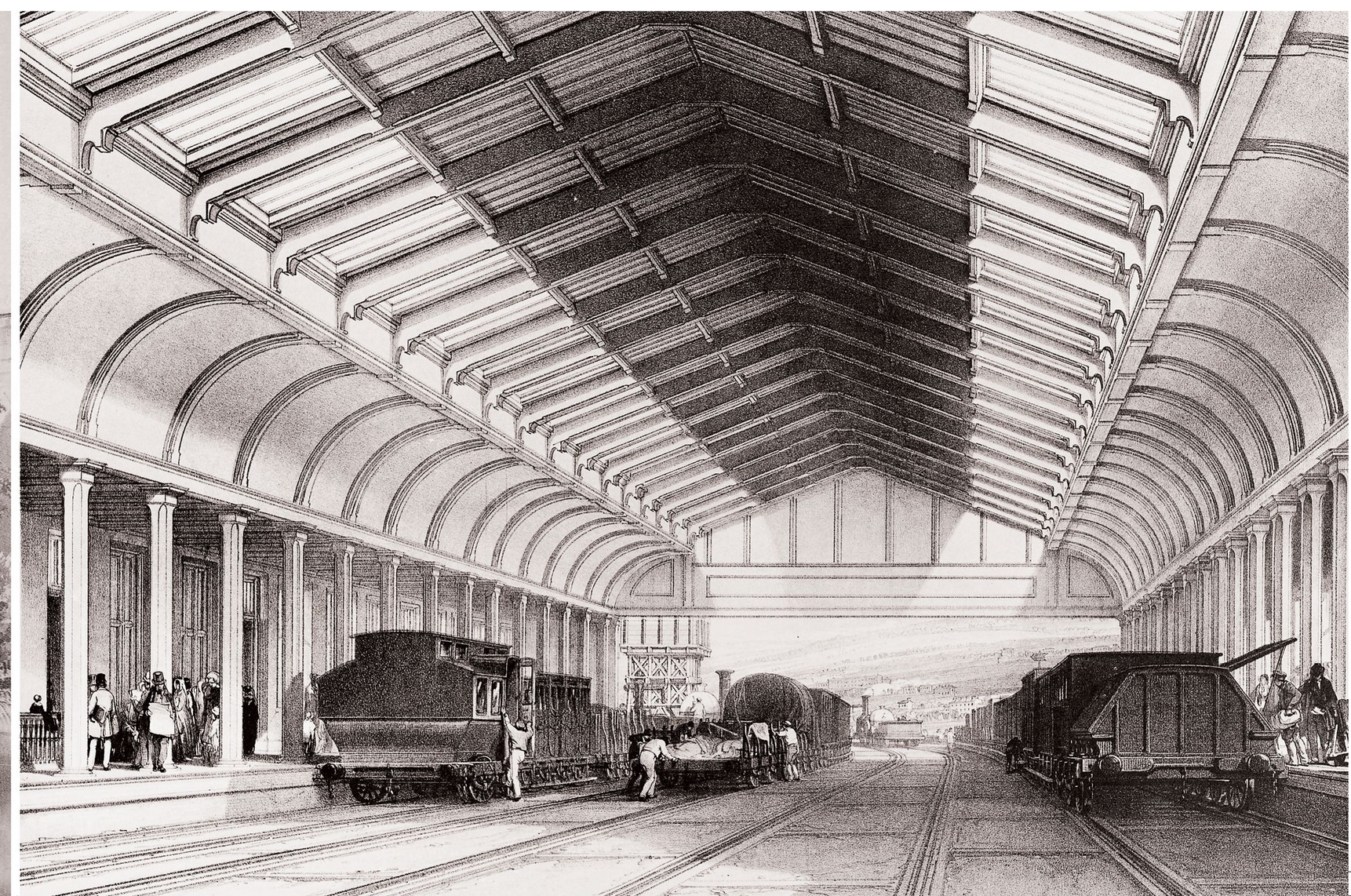

Bath Spa station showing Brunel’s original roof across the platforms, by JC Bourne. BRUNEL 200

He decided to follow the canal and Bristol Avon as closely as possible, crossing the river twice, either side of Bath station, with an acutely skewed stone bridge on the Bristol side.

As a result, Bath’s 18th-century grandeur was left untouched, with the south side of the city left dominated by railway viaducts and embankments.

Brunel designed the splendid two-storey frontage of Bath Spa station in a Jacobean style.

Its platforms were built on an embankment above street level and the original wooden train shed of 1841 had an overall mock-hammer beam roof with a span of 60ft, while the booking office and other facilities lay in the basement.

Again, no expense appears to have been spared in giving the spa resort a station befitting its popularity with the high-class society of the day, even though there were many residents who would rather not have had a railway at all.

Sadly, the roof was taken off at the end of the 19th century, but nonetheless, Bath Spa station still proudly retains many of the superb features of its Brunel-designed architecture, and richly deserves its place in this magnificent Regency city.

The neo-Tudor frontage of Bath Spa station has retained its Brunel design well. ROBIN JONES