Chapter 10

TEMPLE MEADS

The First Great Terminus

The relatively short Great Western Railway route between Bath and Bristol proved to be fraught with difficulties. While none of them were on anything like the scale of the task of tunnelling through Box Hill, seven tunnels were needed on this section, in addition to numerous deep cuttings and a two-mile-long embankment near Keynsham, not to mention a 28-arch viaduct at Twerton, as the railway left Bath. Furthermore, a short section of the Bristol Avon needed to be diverted near Fox’s Wood Tunnel.

The first contract for building work in Bristol itself was placed in March 1836, but difficulties with the contractor and, yet again, prolonged wet weather, delayed completion by at least a year.

The line between Bristol and Bath opened to the public on 31 August 1840, 10 days after Isambard privately treated some of the directors of the GWR’s Bristol committee to the first train trip from there to Bath, behind Firefly class 2-2-2 locomotive Arrow. There was no carriage, so the party had to travel on the locomotive footplate.

When this short section of the trunk route officially opened, more than 5000 passengers were carried on the railway on the first day. Neither city ever had cause to look back.

The Brunel transport revolution continued with the building of Bristol’s Temple Meads station. Predating his stylish rebuilt Paddington terminus by nearly 15 years, it set new standard for others to follow in its wake.

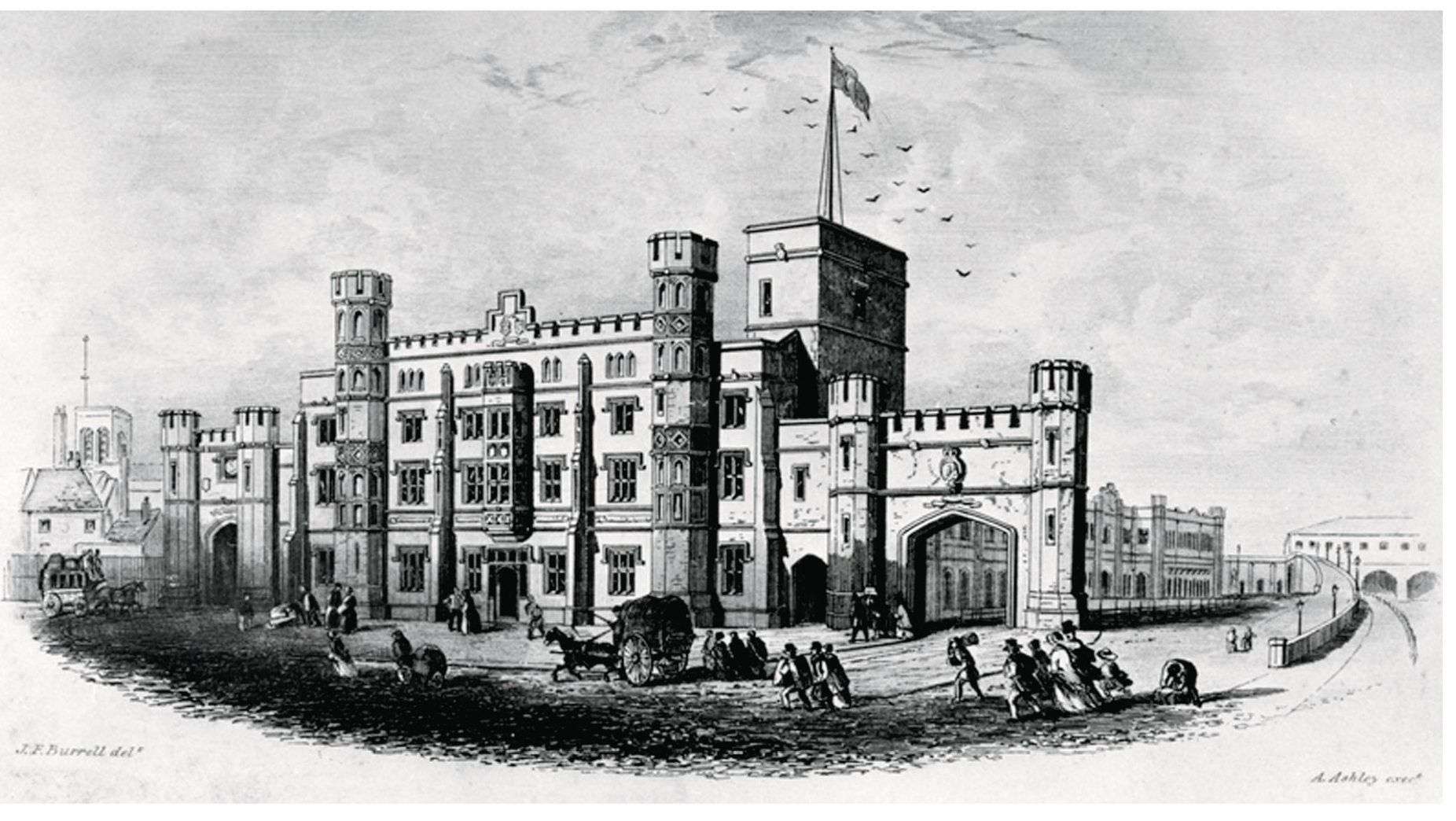

Building work at the site – which lay a fair walk away from the city centre – began in 1838. The frontage on Temple Gate was designed in Brunel’s grandiose neo-Tudor style, with tall square-headed widows and heavy mullions, to screen the engine and train sheds behind it, which were supported by a series of 44 massive brick-flattened arches at 10ft intervals.

Class 47 diesel No 47484, named after Isambard Kingdom Brunel, heads away from the ‘second generation’ Bristol Temple Meads station in July 1985. BRIAN SHARPE

A 74ft single-span hammer beam roof, built entirely from wood, in a direct copy of London’s Westminster Hall, covered the 220ft-long train shed and its five broad-gauge tracks.

The GWR boardroom and booking hall occupied the first floor of the offices that were linked to the train shed, with the station superintendent living on the top floor, and the company clerk’s quarters on the ground floor.

Members of the Bristol committee, possibly disappointed at the very basic facilities originally provided at the Paddington end of the line, had demanded a terminus with architectural features that were in harmony with other buildings in the ancient port, regardless of higher expense.

A letter was sent to the GWR’s London committee arguing that Brunel’s stylish design could be implemented for just £90 more than a basic building resembling a workhouse – and members agreed.

At the far end of the station were facilities for locomotive servicing and maintenance, with chimneys to take the excess steam and smoke away. The station also had its own goods depot.

The completed Great Western main line was opened on 30 June 1841, when a directors’ special left Paddington at 8am and arrived in Bristol four hours later.

By 1845, the timing for an express train between the two cities was reduced to just three hours – light speed at a time when a stagecoach journey from Bath to London could take days, and comparing favourably to the one hour and 40 minutes taken by today’s high-speed trains.

The magnitude of such an achievement can only really be appreciated when you consider the rural and isolated nature of much of Britain at the time. Most towns and village kept their own time, which could vary considerably from that of London. It was only the coming of the railways that allowed standardisation of time across Britain to take place, and eventually facilitated the development of the telegraph system.

The contribution made by railway pioneers like Brunel to the modern world in areas such as this – and so much taken for granted today – was to say the least, immense.

The completion of the GWR opened up all sorts of trade possibilities for Bristolians, who had more reason than ever to be grateful to those Brighton actresses whose ‘exertions’ had led to Isambard convalescing in Clifton.

Even a decade before, such timings would have been seen as nothing less than a miracle, but now the seeds of the period, known as Railway Mania, had been well and truly sown. Not only had trains as a mode of transport been firmly established, with many of the irrational fears about its effects refuted, but the question now on everyone’s lips was – ‘how many lines can we build, and how quickly?’

In 1825, there had been just 27 miles of passenger-carrying railway lines in Britain. By 1841, when the GWR opened throughout its 118-mile length, that figure had risen to 1775.

Brunel’s original Temple Meads station is now in use as the British Empire & Commonwealth Museum, an awardwinning attraction in its own right, highlighting the rise and fall of the empire and its legacy. The broad-gauge tracks long since disappeared; the station’s passenger train shed is now an exhibition hall. One of the themes of the museum is how Brunel became an archetypal Victorian innovator, uniting art and science in his vision for integrated transport. BECM

A contemporary drawing of the exterior of Brunel’s original Temple Meads station. BRUNEL 200

Ever the showman as well as the architect, the western end of this tunnel at Twerton, near Bath, had to be made to resemble a medieval castle. ROBIN JONES

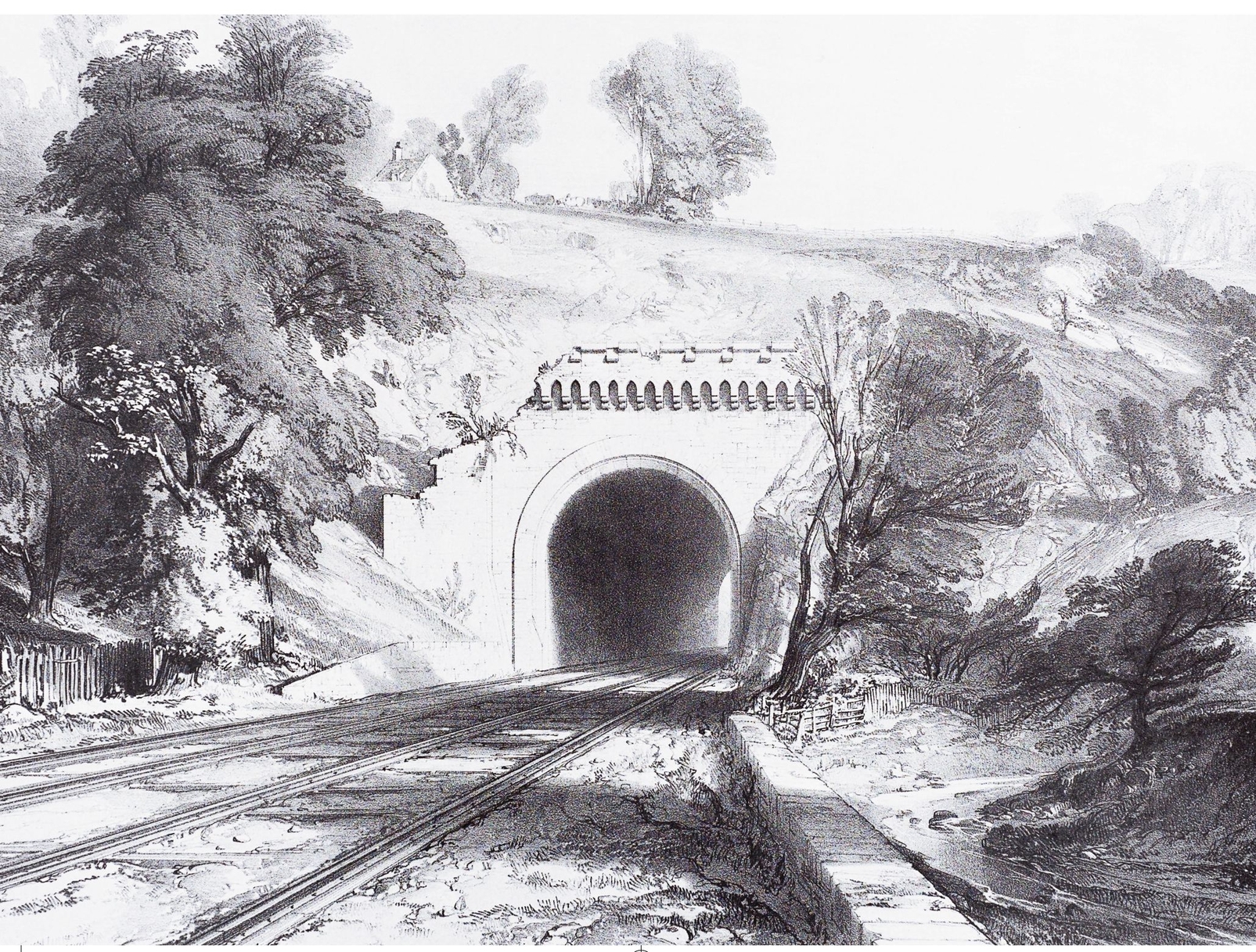

Tunnel No 2 on the GWR near Bristol, as illustrated by JC Bourne. BRUNEL 200

By 1850, it would stand at 6559. Ominously for Brunel and his vision for the future of rail transport, the bulk of that mileage was standard gauge.

In 1845, a second Temple Meads terminus was built, at a right angle to Brunel’s first station building, for use by his ‘next’ line, the Bristol & Exeter Railway, which was also built to broad gauge.

The Exeter line had arrived in 1842, and at first, vehicles had to be transferred between the two railways by means of turntables where the tracks intercepted; moving a complete train one vehicle at a time would take hours.

Eventually, a curve was laid to link the two lines, and it was served by an express platform by through trains. The Exeter trains, terminating at Bristol meanwhile, had to reverse into the GWR station until the second station was built.

Congestion worsened when the Midland Railway acquired the Brunel broad-gauge Bristol & Gloucester Railway, for a higher price than the GWR was prepared to pay for it – much to the Paddington empire’s eternal regret.

The Midland Railway also gained the right to run its trains into the GWR Temple Meads station, and standard-gauge rails were added when the Gloucester line was converted to 4ft 8½in gauge in 1854.

In 1871, the three companies finally sat around a table and agreed to pay for a new joint station to be built.

The Bristol & Exeter’s train shed was knocked down, and a new station designed by that company’s engineer, Francis Fox, was built – right on the curve.

Its distinctive pointed-arched iron roof on lattice ribs was – and still is – 500ft long and 125ft wide. Opened in 1878, it is the stupendous curving Temple Meads that we know today.

Brunel’s station original was kept for trains terminating at Bristol, mainly from the Midland line, and Fox doubled its length with a wider and higher pitched light iron roof that joined to the roof of his new station. The two stations came together in a V formation, and Matthew Digby Wyatt designed an entrance building in French Gothic style, to serve both.

More platforms were added in 1935, but outside the curving train shed. However, Rationalisation in 1966, following the Beeching cuts, left platforms 12-15 taken out of use. Brunel’s train shed was closed, along with the rest of the terminal portion of the station and the tracks inside it lifted. The extension built by Fox became a car park, and in 1970 shortened to make way for a new power signal box.

Thankfully, the massive historical importance of the Old Station, as Brunel’s terminus has come to be known, led to the building being restored and given a new lease of life as the British Empire & Commonwealth Museum.

It has been said that so much of the face of Bristol today has its roots in Brunel and his works, that it would have been unforgivable if this prize asset, on which Bath Spa station was modelled to a large extent, had been allowed to pass into the history books.

Many of Brunel’s magnificent bridges are landmarks, immediately recognisable around the globe, but, some of his finest works remain in comparative obscurity. One example is Devils Bridge, which spans the Bristol & Exeter route at Bleadon near Weston-super-Mare. This wonderful flying arch is the highest single-span railway bridge in the country, at 63ft above the trackbed. The span is 110ft. It is thought that the bridge, which today carries single-file motor traffic on Bleadon Hill, is believed to have acquired its nickname from ‘Devil’ Payne, a local landowner who, apparently, also insisted the BER built him a private station, although refused to stop any trains there. ROBIN JONES