Chapter 11

THE ‘FLYING DUTCHMAN’ IS HERE

The Bristol & Exeter Railway

As might be expected, as soon as everyone saw the potential benefits from Isambard Brunel’s groundbreaking inter-city railway, there were demands for it to be extended to other cities.

When the Great Western Railway Bill received royal assent in 1835, Bristol merchants immediately starting lobbying for it to be extended to Exeter.

Approval for the scheme was granted the following year – and as with the GWR act, the gauge was not stipulated – and Isambard was the clear choice to be appointed engineer.

The first meeting of the Bristol & Exeter Railway Company was held on 2 July 1836. In 1839 it was decided to build the line to Brunel’s broad gauge, and lease it to the GWR, which would provide rolling stock and run the services.

The first passengers were 400 invited guests who were carried on a private train from Bristol to Bridgwater in an hour and 45 minutes, behind Firefly class 2-2-2

Fireball, on 1 June 1841. The line opened to the public on 14 June, along with its curious branch to Weston-Super-Mare – the first Brunel line to serve a seaside resort.

Because local residents objected strongly to dirty steam engines, horses worked this one-and-a-quarter-mile branch – a real throwback for a steam pioneer like Isambard.

However, the blustery winds of the Bristol Channel often pushed the carriages along or held them back, and in one incident a boy in charge of a horse was reportedly thrown in front of a ‘wind-assisted’ train and killed.

Steam was eventually allowed into the growing resort, and the branch and its station was superseded in 1884 by the present-day Weston loop line.

GWR 4-6-0s No 5051 Earl Bathurst and No 7029 Clun Castle storm through Tiverton Junction on the Bristol & Exeter main line route on 1 September 1985. BRIAN SHARPE

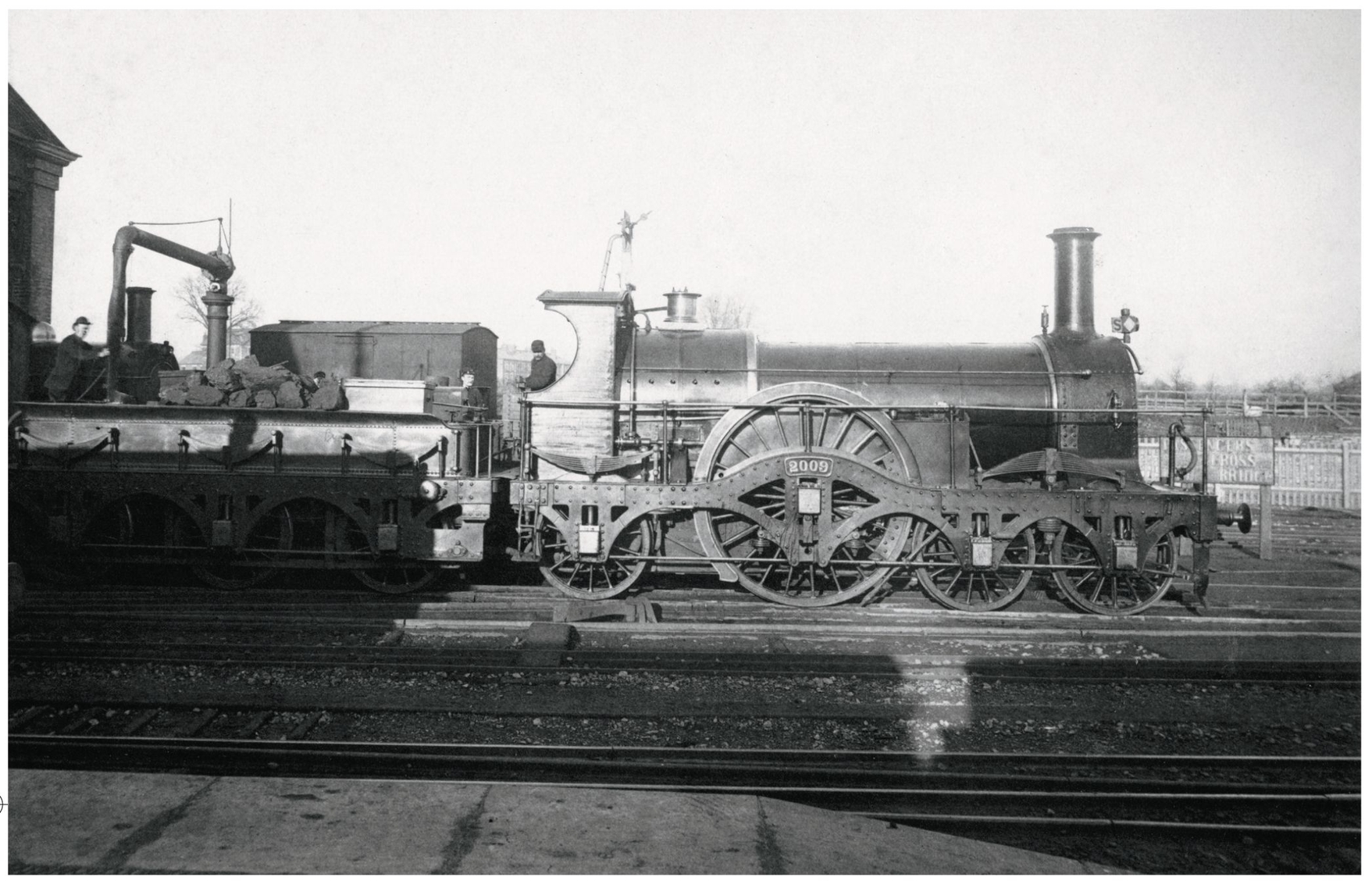

Bristol and Exeter Railway 4-2-2 No 10, as GWR No 2009, at Taunton, after having been rebuilt at Bristol in December 1868. It was one of three of these locomotives withdrawn in December 1888, leaving only No 2008 to carry on until December 1889. CW TRUST

Where Brunel succeeded with flying colours at Maidenhead Bridge, he was defeated on the Somerset Levels when he tried to build a crossing over the River Parrett near Bridgwater, with an arch that was even flatter than that of the Thames model – 100ft long, with a rise of just 12ft.

Movement of the foundations caused weakness and the structure, Somerset Bridge, was replaced with a timber version in 1843, which in turn was replaced by a new steel girder bridge in 1904.

Apart from deep cuttings at Ashton and Uphill, the biggest engineering feat was the 1092-yd brick-lined Whiteball Tunnel. The 1-in-81/90 banks leading to it became world famous after future GWR steam icon, City of Truro hauled the Ocean Mail Express from Plymouth down it at an unofficial speed of 102.3mph on 9 May 1904, staking its claim to being the first steam engine to have exceeded the magic 100 barrier.

The section from Bridgwater to Taunton opened on 1 July 1842, and the completed 76-mile BER main line was opened throughout to Exeter St David’s on 1 May 1844, when Firefly class locomotive Actaeon ran the 388 miles from Paddington and back, driven by Gooch himself.

The best preserved of all the Bristol & Exeter Railway stations is Bridgwater, which is a real architectural gem in this former port town. It became the terminus of the first section of the BER on 14 June 1841, and the company later built a carriage works and a coke oven in the town. There was also a short branch to the town’s docks. The Railway Heritage Trust, established in 1985 by the British Railways Board, to conserve and restore historic buildings on the network, carried out a major renovation of the Grade II listed structure. During the restoration, it was found that the cast-iron balusters of the footbridge staircases were cast by the same firm in Bridgwater that had made the vacuum tubes for Brunel’s ill-fated atmospheric South Devon Railway, as described in the next chapter. Sadly, keeping this marvellous building as close to its original condition as possible is hampered on a regular basis by graffiti-daubing vandals. ROBIN JONES

The average speed for the outbound five-hour journey, inclusive of stops was 39mph, and on the way back cut 20 minutes off the scheduled time, averaging 41½mph.

The completion of the BER led to locomotive performances of a magnitude, which, until then had never been seen anywhere in the world. Five-hour Exeter expresses began on 10 March 1845, and when an extra stop was added at Bridgwater, a further five minutes was cut off the journey. What the GWR main line had in grandeur, the flattish BER gained in speed.

Among the 9.50am Exeter-Paddington expresses, which ran between 1847 and 1852, was the fastest train in the world, nicknamed the ‘Flying Dutchman’, after the racehorse that won the Derby and the St Leger in 1849. Among engine crews, ‘stoking the Dutchman’ became a term for hard physical work.

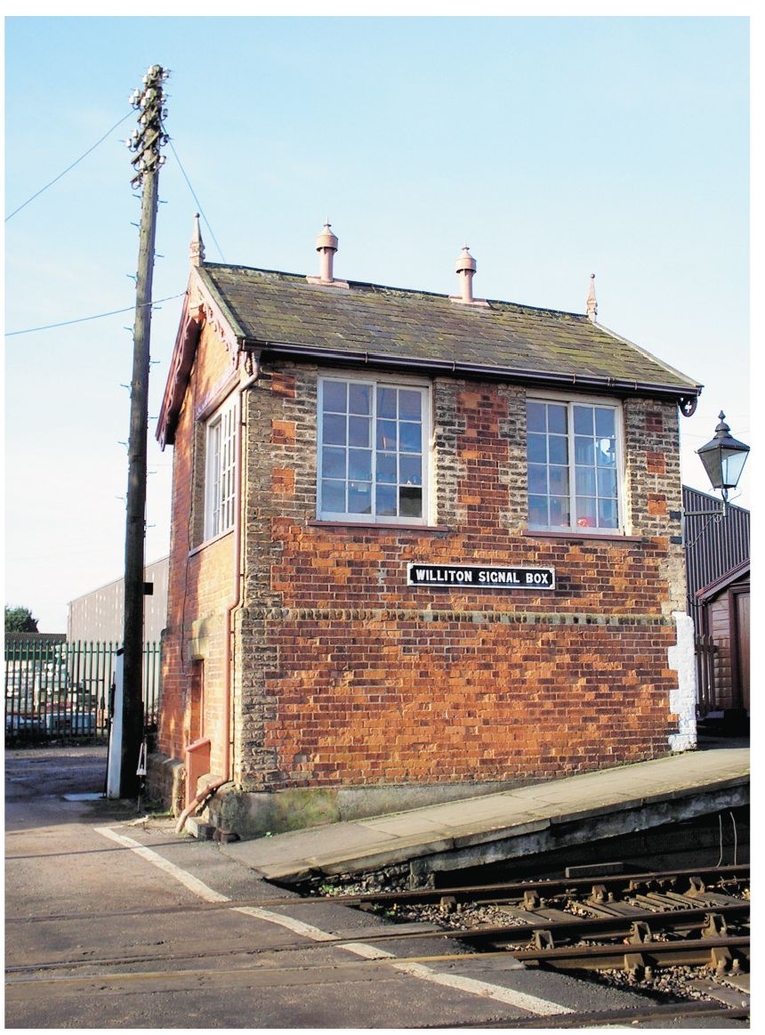

The signalbox at Williton on the privately owned West Somerset Railway, is the last Bristol & Exeter one in regular use today. WSR ASSOCIATION

Whereas many Brunel projects exceeded budgets, often because of his grandiose structures, the BER was built for less than the allocated £2-million.

We have already mentioned how the coming of the railway led to standardisation of time across the country; at Exeter, an extra minute hand was added to a clock in Fore Street, in order to show both railway time and Exeter time.

The first rail-borne tourists began to arrive, and among them were an elderly Marc Brunel and his wife, carried there by his son’s railway. Tourism by train to Exeter became big business from 1850 onwards, and paved the way for the railway to open up the West Country as Britain’s premier home destination for summer holidays.

The BER thrived under the operation of the GWR, who had an offer to buy it in 1845, which it turned down. Four years later however, the GWR lease ran out and BER decided to run its own line, having ordered its own fleet of engines, 10 each from Stothert & Slaughter of Bristol and Longridge & Co from Bedlington, all smaller versions of Gooch’s GWR Iron Duke class.

In September 1854, BER erected its own locomotive workshops at Temple Meads, and five years later turned out the first of 23 broad-gauge engines of its own. The works, which also produced 10 standard and two 3ft gauge engines, later became known as Bristol Bath Road, and would become a famous steam depot in the century to come.

Eventually, BER owned 149 engines, with all but 30 being broad gauge.

Royal assent to build a 14-mile branch from Taunton to Watchet was granted on 17 August 1857 – again with Brunel as engineer and using his broad gauge.

Brunel surveyed the route and work began between Crowcombe and Watchet on 10 April 1859. The line opened on 31 March 1862, its owner, the West Somerset Railway Co, leasing it to the BER. It was extended to Minehead on 16 July 1874, and was the last new BER-operated route before that company was finally taken over by the GWR.

The lease of the Somerset & Dorset to the Midland Railway and the London & South Western Railway angered both the GWR and the BER, so they joined forces to fight the competition.

Thirty years before, however, a brief alliance of the GWR and BER with the Bristol & Gloucester Railway, prior to its aforementioned purchase by the Midland, discussed pushing further westwards from Exeter, using broad gauge, and on 4 July 1844, the South Devon Railway received its Act of Parliament to build a line to Plymouth.

However, as we shall now see, it was not to be like any main line railway that the world had seen before, and it was to prove one step too far for Isambard Brunel.