Chapter 14

BRUNEL’S SECOND PADDINGTON

The Ultimate Great Western Station

The phenomenal success of Isambard Brunel’s London-to-Bristol railway was such that both termini had to be replaced to cope with greater traffic. As previously stated, the original scheme included in the Great Western Railway Act of 1835, involved sharing Euston with the London & Birmingham Railway. That was scuppered by a row over land at Camden and Euston, and GWR’s movement towards adopting broad gauge.

In July 1837, parliamentary permission was given to build four miles of new line from Acton, to a location next to the Paddington Canal.

The first GWR Paddington station in Bishop’s Road was most likely built ‘on the cheap’ while Isambard awaited sufficient funds to build a far grander design. Its four platforms and plain, wooden-arched, truss-roofed train shed, open to the elements at both sides, was very different from the exquisite terminus he had built at Bristol.

By the late 1840s, the old station was hopelessly outdated, yet the GWR board was reluctant to approve its replacement.

By the end of the railway mania years in 1847, company share values had plummeted. The GWR had to face down angry shareholders in 1849 and tell them that their dividend was being cut from four per cent to two.

However, the directors knew that the station was becoming hopelessly inadequate, and could lose the company business. In late 1850, they changed their minds, and on 21 December, gave Isambard the green light to build a main terminus worthy of both the capital and the GWR. Needless to say, he had already been making preliminary sketches in anticipation of that inevitable decision.

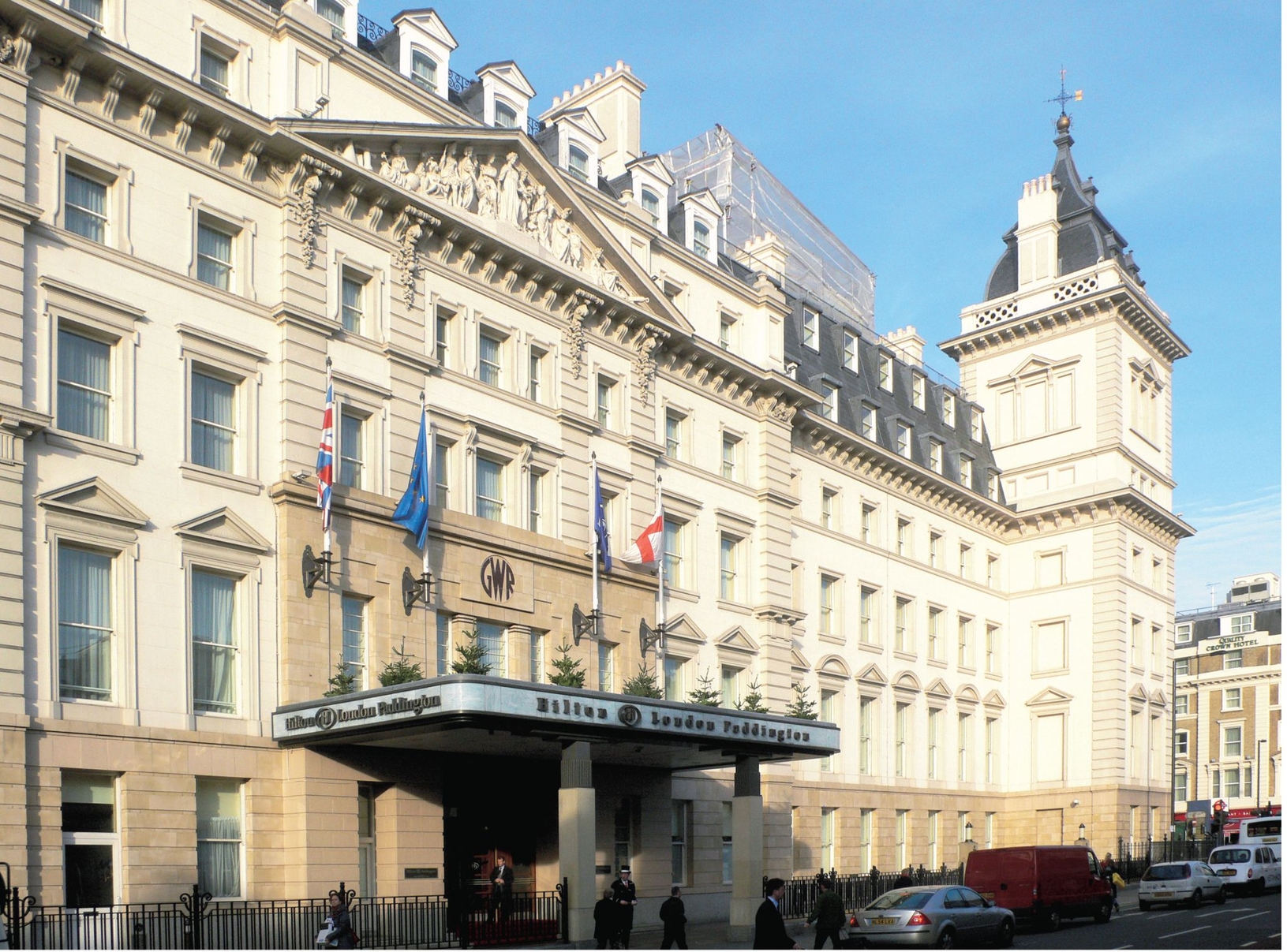

The ultimate in quality when it opened in 1854, the Great Western Royal Hotel was fully refurbished in 2001 and reopened as the Hilton Paddington Hotel. Like the station, it too, is of immense historical importance. ROBIN JONES

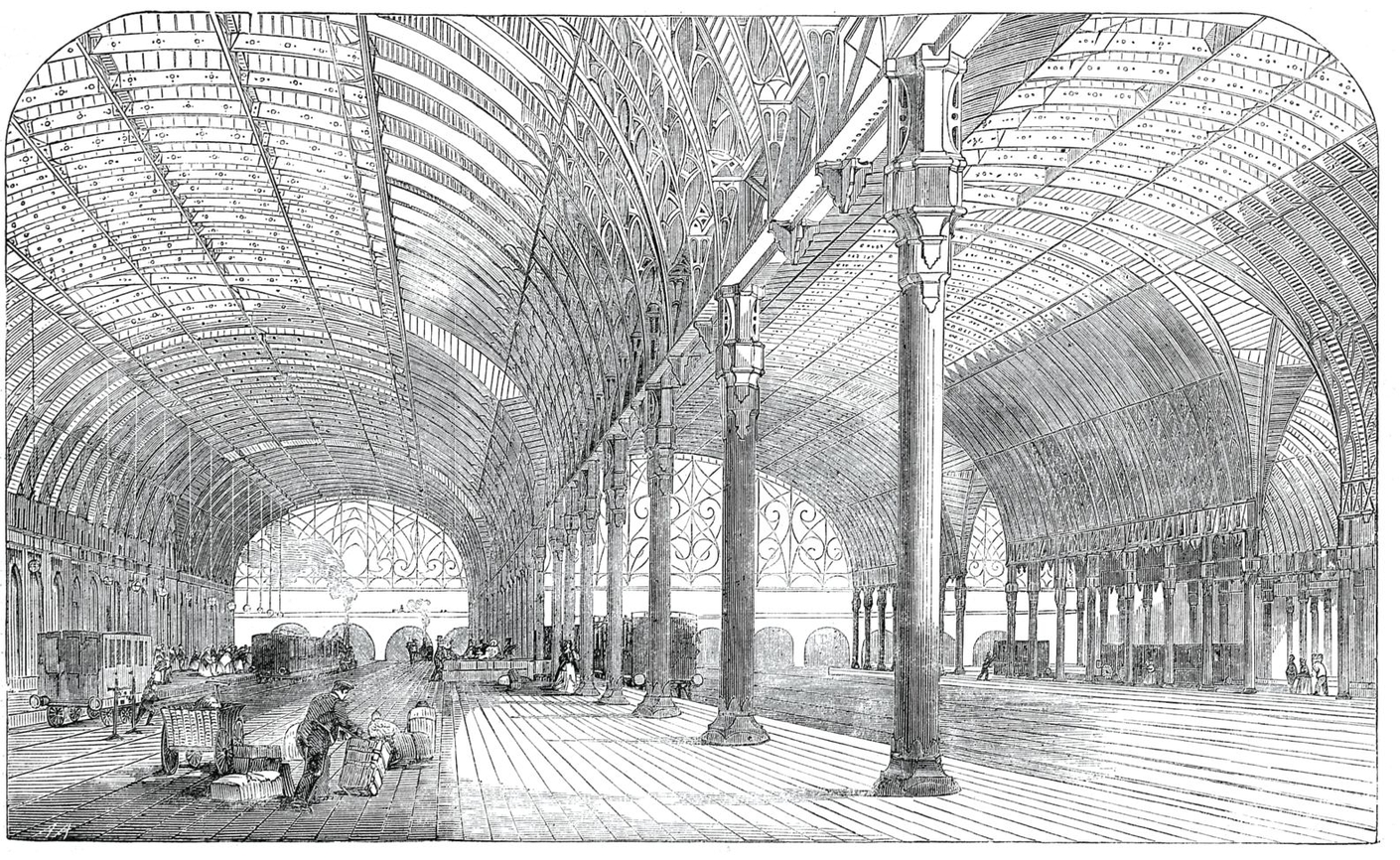

Isambard’s design for Paddington, mark two, which was between Praed Street and Eastbourne Terrace, included a train shed 700ft long and 238ft wide, with 10 tracks, five to serve platforms and five to store stock. Consisting of three spectacular, wrought iron, arched, roof spans, it was supported by two rows of cylindrical, cast-iron columns.

Much of Isambard’s inspiration for the new terminus was drawn from the ‘glasshouse technology’ of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, in which the Great Exhibition of 1851 had been held. Brunel’s friend, Matthew Digby Wyatt designed the ironwork for the ornate glass screens at the west end of the station, while Paxton’s ‘patent glazing’ was utilised for the roof lights.

The first train departed from the new station on 16 January 1854, when work on the main roof was still being finished. The new arrival side was finally brought into use on 29 May.

Paddington station has been altered many times since it was opened in 1854, but the triple-roof span is still an awesome tribute to its designer, Isambard Brunel, and the phenomenal success of the line to Bristol, which necessitated the replacement of the inferior original. ROBIN JONES

On 5 December 1850, the GWR board took on board a suggestion from director George Burke that a luxury hotel should be built to serve – and complement – the magnificent new terminus.

The completion of the GWR route from Oxford to Birmingham had, for the first time, placed the company in direct competition with the successor to the London & Birmingham Railway – the London & North Western Railway.

The rival company had opened a pair of hotels at Euston in 1839, and the GWR knew only too well that it could not afford to fall behind.

The Great Western Royal Hotel, as it was named, was the first in the capital to be designed as a major architectural statement, and marked a crucial development in the style and opulence of hotel architecture.

Philip Charles Hardwick drew up plans in the French renaissance style of Louis XIV – the huge mansard roof between corner towers creating a chateau-like impression. The building was also the first significant example in Britain, of what became known as the Second Empire style.

A commemorative plaque at Paddington honours Brunel.

The hotel was opened on 8 June 1854 by Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, and his guest the King of Portugal.

Having 112 bedrooms and 15 sitting rooms, plus lounges, public rooms and restaurants, the Great Western Royal Hotel was hailed as the “largest and most sumptuous hotel in England.” It set new standards for accommodation in Britain, in terms of size, comfort and amenities for guests.

The design of the second Paddington station served GWR for more than 40 years, justifying Isambard’s efforts.

Traffic continued to grow, however, and removing some of the stock sidings and adding extra platforms, expanded the station’s capacity.

While mixed gauge had been rejected at Euston, it became the norm at Paddington in 1861, when the first standard-gauge rails were laid in the station. They served the lines leading to the West Midlands, which had become part of the expanding GWR empire.

Paddington was linked by a footbridge to Bishop’s Road station, which served the Metropolitan Railway’s line into the City of London, which opened in 1863.

That line was worked at first by the GWR as broad gauge – and was the easternmost extremity of the 7ft 0¼in gauge empire. However, it was soon taken over entirely by the Metropolitan, with whom the GWR then built the Hammersmith & City line.

GWR 4-4-0 No 3440 City of Truro stands at Paddington after arrival from Derby in May 1992. BRIAN SHARPE

Modifications to Isambard’s original design have included station offices in 1881, additional departure platforms in 1885, and more arrival platforms in 1893.

Isambard’s station needed updating once more in the early 20th century, when the route to the West Country was shortened by the building of ‘cut-off’ lines, Fishguard Harbour proved to be a major new gateway to Ireland and new powerful locomotives, designed by George Jackson Churchward, all combined to create a phenomenal expansion of traffic.

Brunel’s second Paddington station could not cope, and so a new roof span, built from steel instead of wrought iron, was completed in 1915, the year before yet more platforms were built.

Further expansion of Paddington took place between the two world wars, with the GWR drawing on government funds to alleviate unemployment during the depression, in order to modernise the station. The platforms were extended and a new concourse provided.

During the remodelling, the once-separate Metropolitan Bishop’s Road station lost its separate identity and was absorbed into the main station.

By 1939, Paddington offered some of the finest passenger facilities anywhere in the country.

It took a pounding during WWII, with more than 400 incidents, although thankfully, there was only one major hit, when a 500kg Nazi bomb broke one of the roof ribs in 1944.

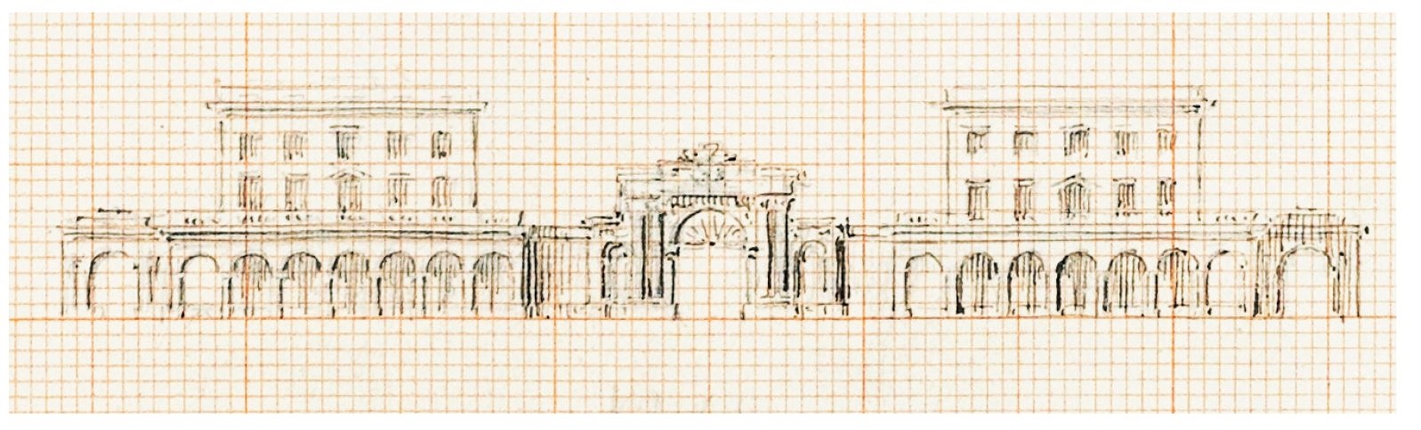

Brunel’s rebuilt Paddington station. BRUNEL 200/ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS

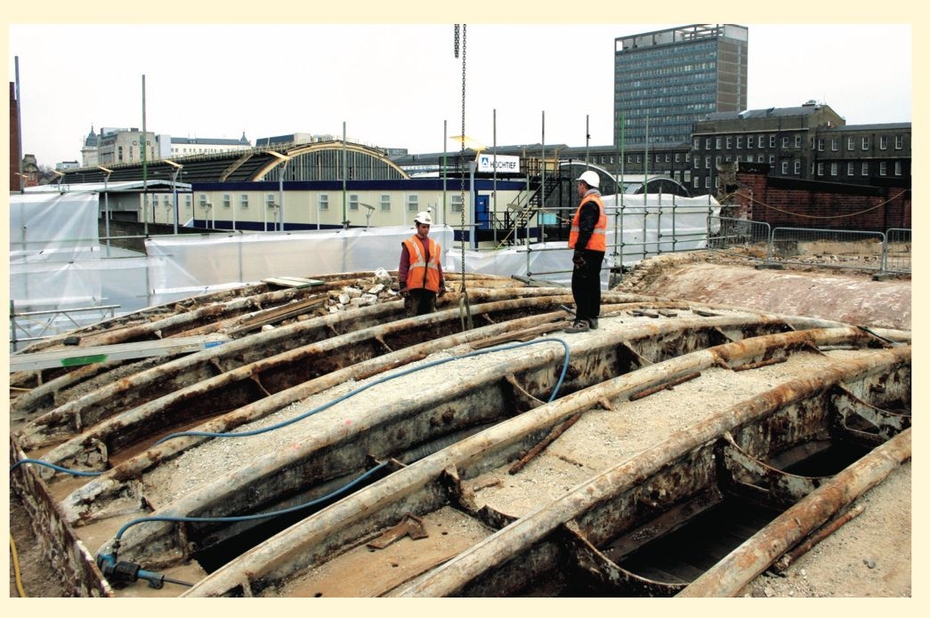

It is still possible to rediscover major Brunel gems in the 21st century, as proved by English Heritage inspector, Dr Steven Brindle, who stumbled upon Isambard’s iron bridge, just as it was about to be demolished in ignorance of its immense historical value.

The bridge, unique and a typically inspired Brunel design, was built in 1838, without bolts, but locking together like a jigsaw.

It crossed the canal next to Paddington station and in 1906 was covered by brickwork and entombed inside Bishop’s Bridge Road, one of the most notorious traffic bottlenecks in London.

When its true significance was realised in 2003, Westminster City Council ordered the work to be halted, so the bridge, complete apart from its original decorative iron railings, could be carefully dismantled and stored, pending hopeful re-erection over a nearby arm of the canal, now part of the Grand Union system.

Journalist Jeremy Clarkson, who championed Brunel in the BBC 2004 series Great Britons, in which the engineer came second, said: “It is astonishing to think that in a city like London, such an extraordinary part of our industrial past could lie unknown and undiscovered.” PHIL MARSH

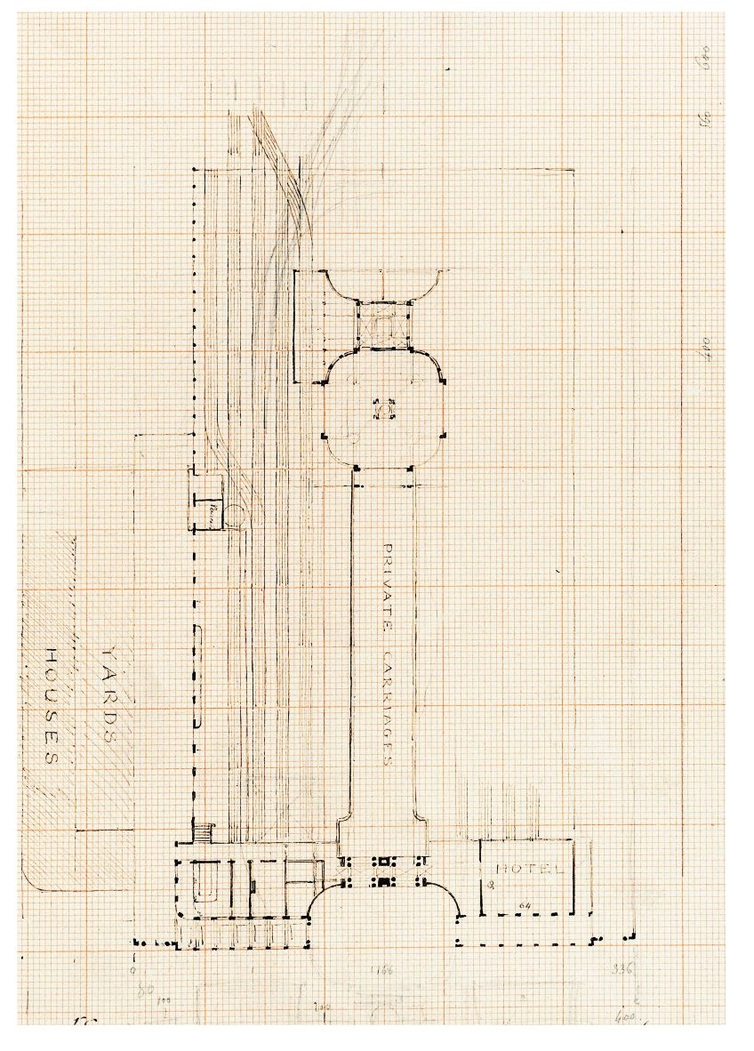

The platform layout at Paddington on Brunel’s blueprint. BRUNEL 200

Only after the end of steam on British Railways were more major improvements made to Paddington, including, in the late 1980s, the complete restoration of Isambard’s triple-span roof, which took several years to complete. Needless to say, it led to a tremendous improvement in its appearance, and thankfully much of the ambience of the 1854 station and its companion hotel can again be appreciated today.