Chapter 15

BROADENING HORIZONS

Brunel’s GWR Empire Expands

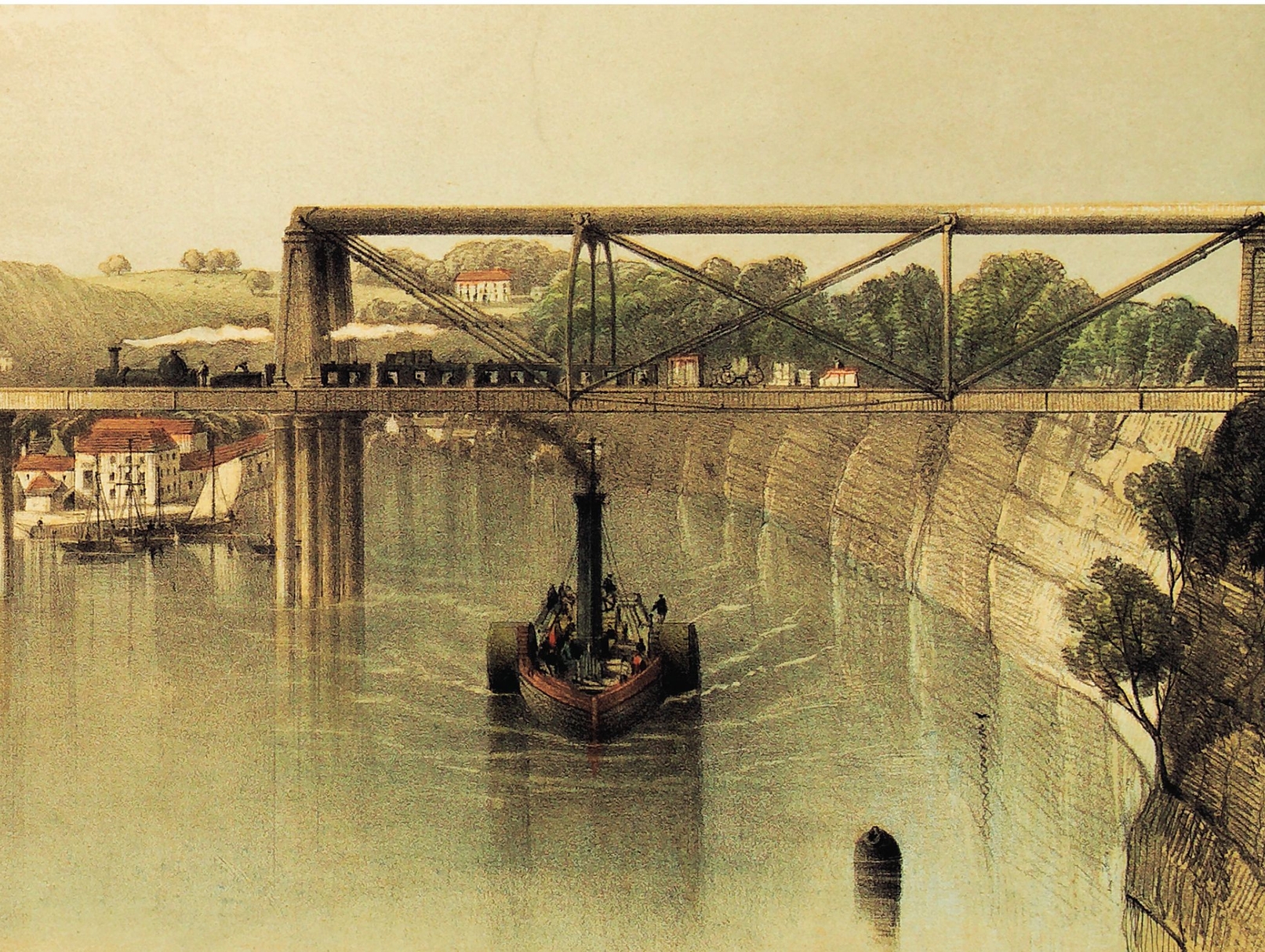

Isambard Brunel’s tubular suspension bridge for the South Wales Railway across the River Wye at Chepstow, provided a direct rail link to London. ELTON COLLECTION, IRONBRIDGE GORGE MUSEUMS TRUST

At one stage, Isambard Brunel had toured the country looking for work. By the 1830s, offers were coming at him from all directions. Not only had he been placed in charge of turning the Great Western dream into reality, but other new railway companies were also clamouring for his services.

He was given the job of engineer to the Cheltenham & Great Western Union Railway, which held its first meeting in September 1835. He surveyed a route through Stroud and the Chalford Valley, but due to initial opposition – not least of all from the Thames & Severn Canal, the route of which his planned line followed – and the company’s inability to raise sufficient finance, the Swindon-Cirencester section was built first.

Leased to the GWR to save buying engines and rolling stock, the new broad gauge railway’s Swindon-Cirencester section opened on 31 May 1841. With an eye on a route to the South Wales coalfields, the GWR stumped up the additional capital to finish the route to Cheltenham on 12 May 1845.

Completed at last – but problems were just beginning for Isambard, for at Cheltenham, his line from Swindon met the standard gauge Birmingham & Gloucester Railway. The two companies eventually agreed to share a line between Cheltenham and Gloucester, and a rail was laid between the 7ft 0¼in gauge tracks to allow 4ft 8½in gauge trains to run along them. This was the first example of mixed gauge on a main line.

Isambard Brunel meets Irish 5ft 3in broad gauge: Great Southern & Western Railway J15 class 0-6-0 No 186 rounds Bray Head with a Railway Preservation Society of Ireland special from Dublin to Waterford on 12 May 2005. The tunnel in the distance is on Brunel’s original Waterford, Wexford, Wicklow & Dublin Railway alignment, since replaced by a longer tunnel further inland because of serious coastal erosion. BRIAN SHARPE

A simple enough solution? No way, for at Gloucester, what became known as the Battle of the Gauges broke out. On a basic level, this was simply about the inconvenience of both passengers and freight having to switch trains where Brunel’s broad gauge ended and standard gauge began, for apart from mixed gauge sections, there could be no through working. The interchange depot at Gloucester never managed to cope in the way that Brunel promised it would; it caused frequent delays of more than five hours and disruption to the transhipment of freight, all of which were seized upon by critics of the broad gauge.

Another company that took on Isambard as engineer was the Bristol & Gloucester Railway, which he persuaded to adopt 7ft 0¼in gauge rather than the originally planned standard gauge. However, this line joined forces with the Birmingham & Gloucester Railway in January 1845, and the pair became the Bristol & Birmingham Railway.

The new joint concern wanted the GWR to extend broad gauge via its route to Birmingham, but talks broke down, and rivals Midland Railway then bought the Bristol & Birmingham.

Not only did it end Isambard’s dream of Birmingham to Bristol broad gauge, but left Gloucester as a permanent break of gauge, and in doing so cast doubts on the long-term survival of the 7ft 0¼in system.

In 1844, Isambard surveyed the route for the projected Oxford, Worcester & Wolverhampton Railway and another from Oxford to Rugby via Banbury, both of which were to be broad gauge. The plans meant penetrating deep into the heart of the territory of GWR’s rivals – the London & Birmingham Railway, which opposed them and came up with alternative routes of its own.

A panel of five commissioners of the Board of Trade met to decide which of the opposing schemes should be allowed to proceed, and after first taking a stand against broad gauge, eventually supported it.

In early 1845, broad gauge critic Richard Cobden MP, persuaded the House of Commons to consider the need for a uniform gauge across Britain’s railway network to be investigated by a Royal Commission.

Isambard gave evidence on 25 October 1845, answering 200 questions, and said that if he had his time all over again, he would still choose broad gauge, despite severe criticism from fellow railway pioneers like Robert Stephenson.

He was also asked why, when he was appointed engineer of the Taff Vale Railway in 1836, as well as taking a key role in the construction of a line from Turin to Genoa in Italy, he had allowed those lines to be built to standard gauge if he was convinced that 7ft 0¼in was superior. He said that in both cases, the higher speeds, which were then a distinct advantage of broad gauge, were not a priority.

Isambard persuaded the commissioners to hold a series of tests to measure the performances of locomotives of both gauges against each other. This event became known as the Gauge Trials, and was a turning point in British railway history.

As previously mentioned, a Daniel Gooch Firefly 2-2-2, Ixion, easily outperformed a Stephenson ‘long boiler’ standard-gauge engine, No 54, which even derailed during one test run.

The commissioners retired to consider their verdict, which they delivered in 1846.

They acknowledged that Brunel’s gauge was superior to 4ft 8½in, in terms of speed, safety and passenger convenience, and praised the design of his railways.

However, they said these factors mattered less than the general commercial traffic needs of the country, and in terms of nationwide freight shipment, standard gauge was better.

Could their verdict have been anything but biased against hard facts as presented by Isambard? At the time of the trials, there were just 274 miles of broad-gauge railway, but 1901 of standard gauge. It was so much more convenient and cost effective to let VHS win the day, and sound the death knell for V2000. Needless to say, Isambard was furious.

In July 1846, Parliament passed ‘an Act for the Regulating of Railways’, stipulating the new lines should be standard gauge, except where any future Act empowering a particular line gave special powers to choose a different width between the rails.

The short and medium-term message to Isambard was simple: carry on building broad gauge. But in the longer term…

He then turned his attention to the 90-mile Oxford, Worcester & Wolverhampton Railway, which now had the green light as a broad-gauge route.

The construction of this route became fraught with difficulties; not least of all the company’s financial difficulties, but more spectacularly, an incident, which became known as the Battle of Mickleton Tunnel.

During the boring of the tunnel beneath the Cotswold Hills, near Chipping Campden, Isambard became involved in a dispute with the contractors, Robert Mudge-Marchant, over payment.

Despite being warned by magistrates that he would be causing a breach of the peace, on 17 July 1851, Brunel arrived at the tunnel site with an army of navvies to evict the contractor – the Riot Act had to be read to ensure peace.

Brunel was back the next day with more navvies, and a series of fights broke out, though not on the scale that the authorities had feared. He won the day, and forced the contractor to reach a settlement.

However, during a national recession, funds for building the line fell short, leaving shareholders angry at GWR’s failure to invest sufficient capital to make up the shortfall. Eventually, it was opened in stages – but as a standard-gauge line, and The GWR’s successful march to Birmingham began on 12 June 1844 when it opened a 12-mile branch from Didcot to Oxford, having amalgamated with the scheme’s promoter, the Oxford Railway, 33 days previously.

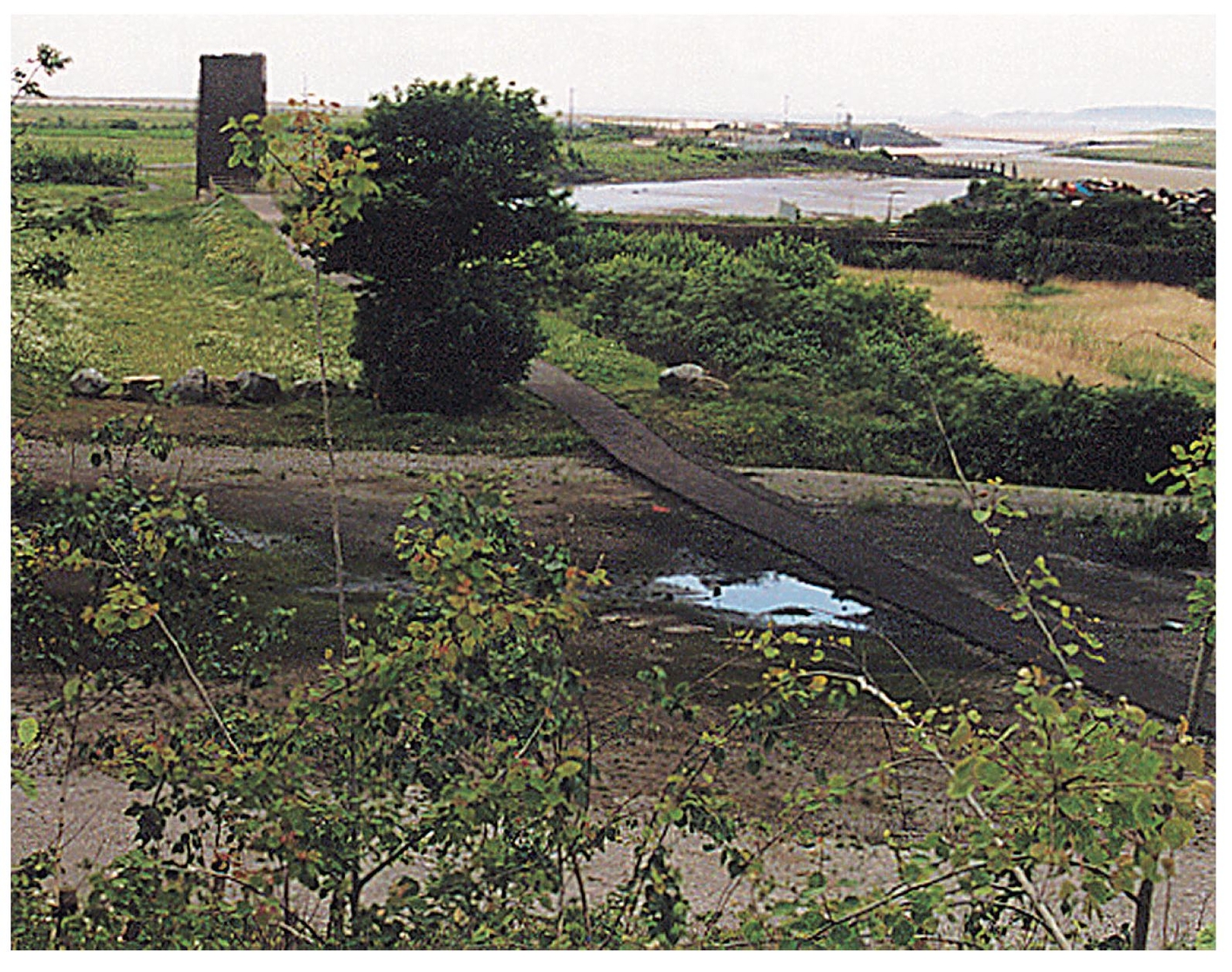

The sole-surviving building from the Isambard Brunel era at Briton Ferry Dock is this tower at the entrance. Local authorities have now assembled a funding package to investigate the possibility of restoring the dock.

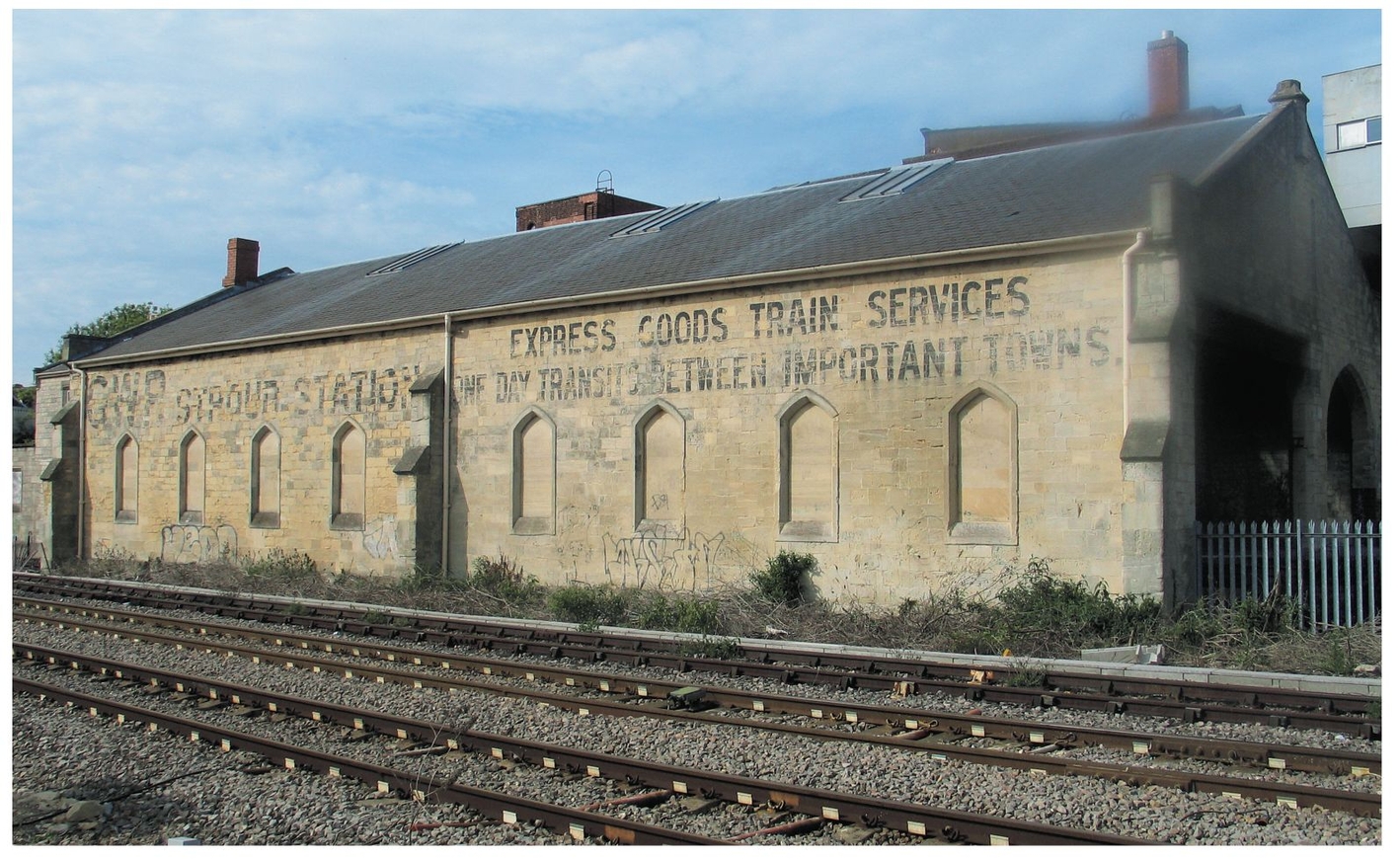

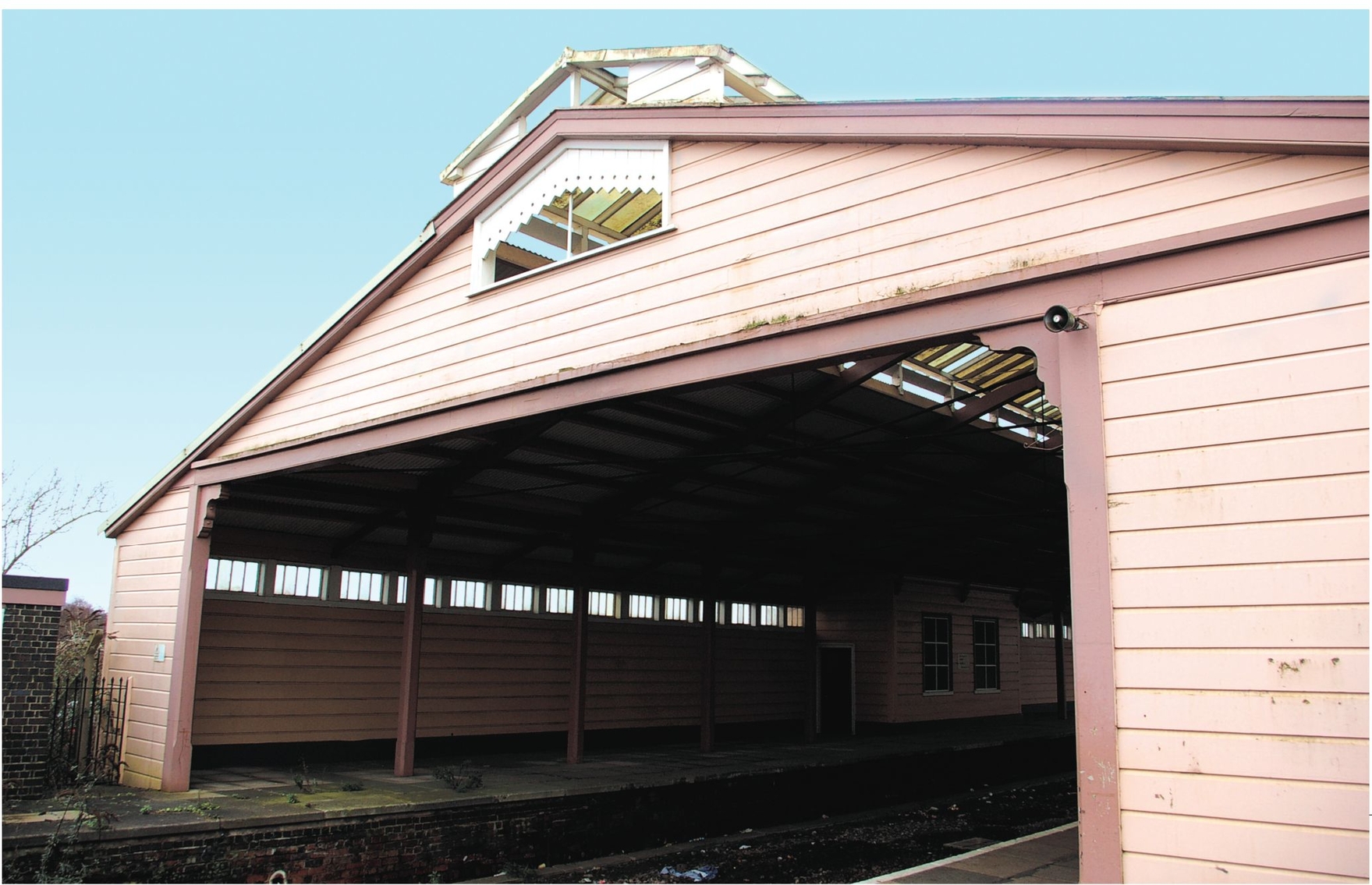

As well as the magnificent viaducts in the Chalford Valley, Isambard Brunel also built Stroud station, which includes his office dating from 1845, now Grade II listed, and the nearby goods shed, which is afforded similar protection. The Stroud Brunel Group wants to renovate this structure, thought to be the last remaining Brunel-designed goods shed in existence, and turn it into an exhibition. It was also a focal point of activities to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth in 2006, culminating in the Stroud Country Show on 15 July. STROUD BRUNEL GROUP

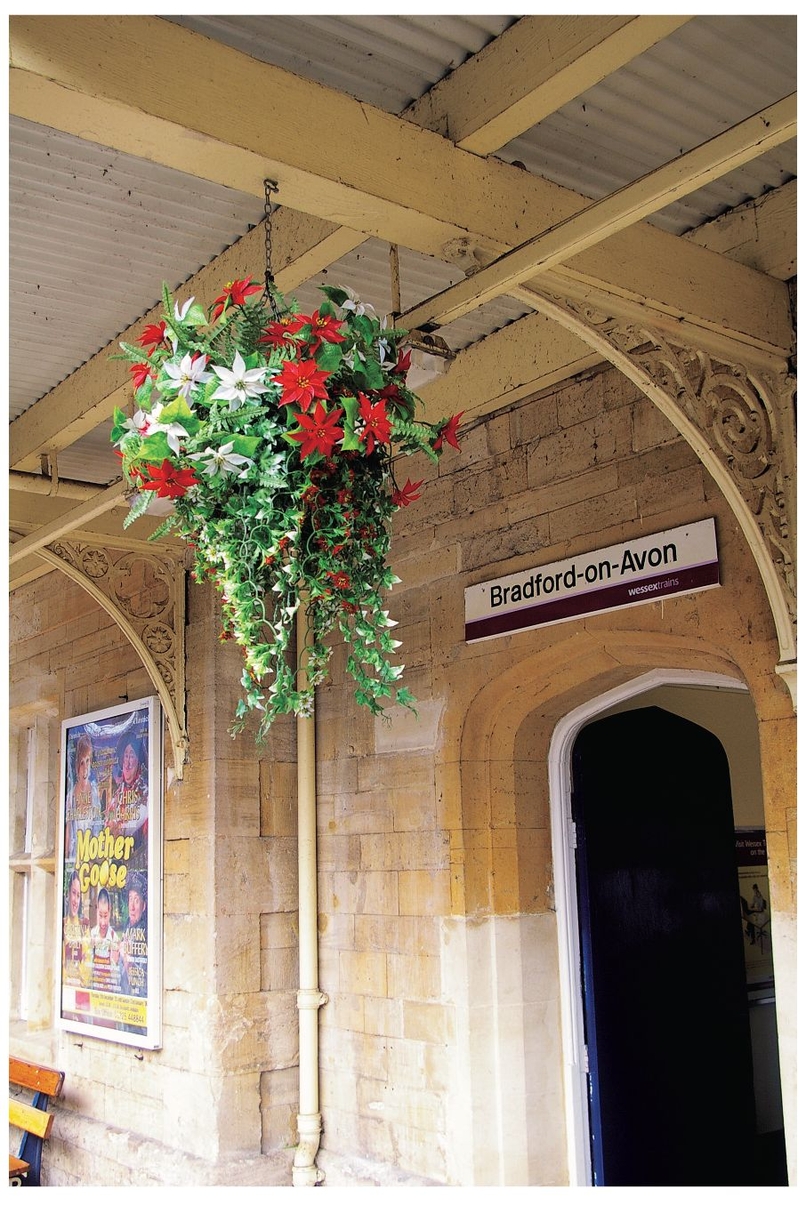

One of the real delights of rediscovering Isambard Brunel’s much-varied works is finding little gems that are never mentioned in the same league as Clifton Suspension Bridge or Box Tunnel. Creamy Bath stone was used to build Bradford-on-Avon station on the Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth Railway in Brunel’s Tudor station. The Grade II listed building was recently restored. ROBIN JONES

Cirencester has not been directly served by rail since the 1960s, but the station building still survives in the town centre, with a plaque to remind passers-by that it was built by Isambard Brunel. This line was built as the first stage of the Cheltenham & Great Western Union Railway, but later became a branch line from Kemble. ROBIN JONES

The front of Frome’s wooden trainshed, a Brunel building made of cheaper materials than stone, but which has stood the test of time. ROBIN JONES

The all-encompassing train shed was a delightful feature of Isambard Brunel’s railways, but the sole survivor on the national network is this splendid Grade II listed example at Frome, designed by JR Hannaford and still in daily use. Timber was used for economy. ROBIN JONES

The Oxford & Rugby Railway was promoted at a public meeting on 18 May 1844, attended by several top GWR officials, including Isambard. He argued in vain that the line should first be built to Birmingham, not Rugby.

The Oxford & Rugby received its enabling Act of Parliament the following year, and work started on 4 August 1845.

The Rugby option was eventually discarded in an attempt to reduce opposition from rival companies to GWR schemes elsewhere, and so the line proceeded north to Banbury, to which trains first ran on 2 September 1850, reaching Fenny Compton on 1 October 1852.

A scheme to build a Birmingham & Oxford Junction Railway and associated lines to Wolverhampton and Dudley received Royal Assent on 3 August 1846, but legal wrangling meant that it would be two years before final approval was given for the work to start under the GWR, which had acquired these concerns. The same empowering Act also allowed the GWR to lay broad-gauge rails as well as standard gauge on these lines.

In Birmingham, the station was earmarked for a site at Snow Hill, being reached from the edge of the city centre at Moor Street by way of a deep cutting, which was then covered over to form Snow Hill tunnel, with the land on top sold for development. At first a basic wooden shed was provided as a station, before it was taken down and re-erected at Didcot as a humble carriage depot. A much bigger replacement was built in 1871.

The Birmingham & Oxford also opened to passengers on 1 October 1852, the day after a directors’ special had been run over the 129 miles from Paddington, behind Daniel Gooch’s Lord of the Isles – then just three months old, and fresh from the Great Exhibition.

By the time the train reached Aynho, it was half an hour late. As a result, the crew of a mixed-goods train who were uncoupling wagons were unaware of its approach.

The crew finally heard the special, and the driver tried to pull away, but snapped a coupling and left all of his carriages and wagons behind. A collision was inevitable, the special was derailed, but nobody was seriously injured, and the directors completed their journey the following day.

The first Paddington-Birmingham expresses were scheduled to complete the 120-mile journey at an average speed of 47mph.

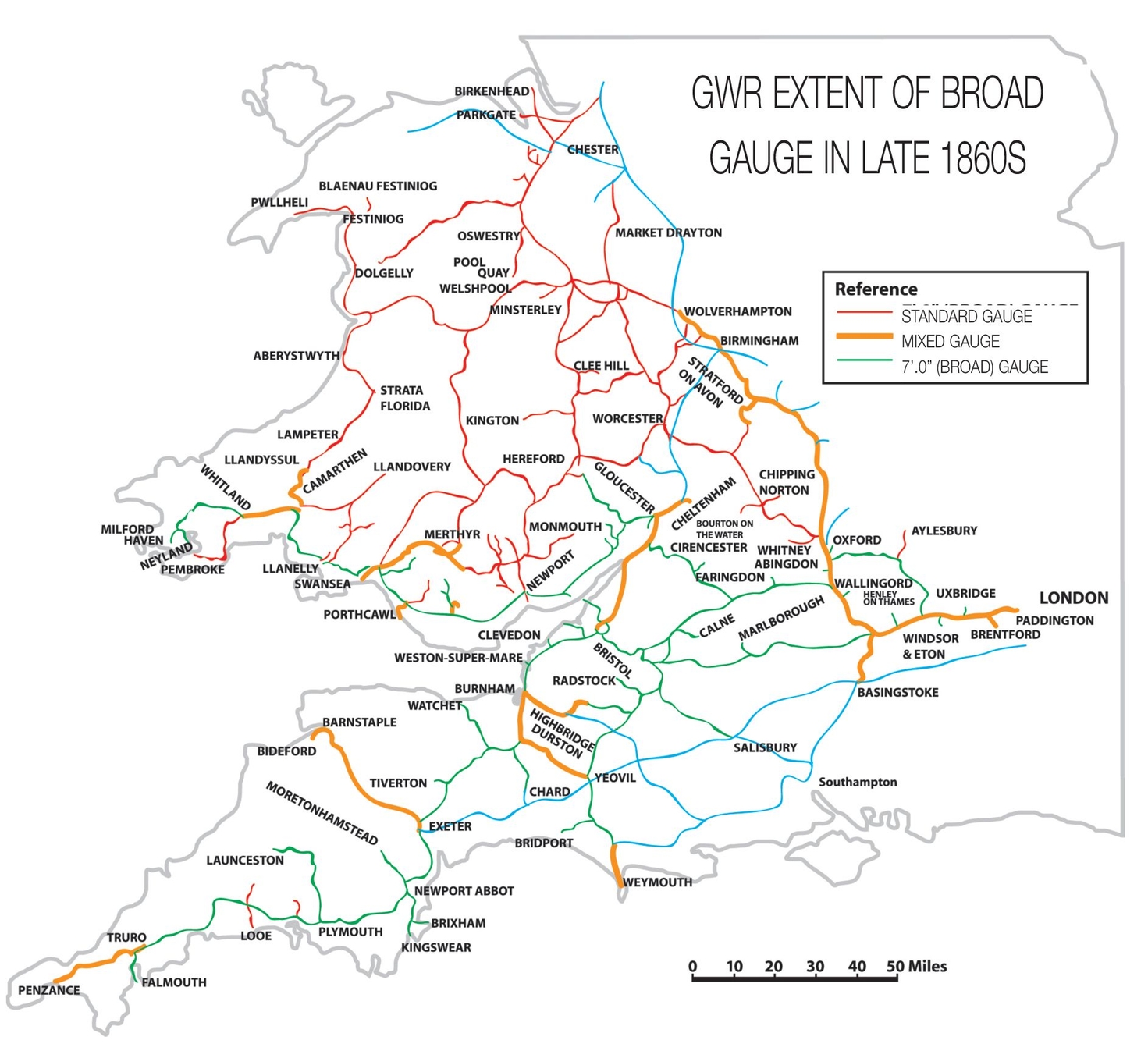

The broad gauge was subsequently extended from Birmingham to Wolverhampton, but no further. Wolverhampton remained its northernmost extremity, dashing Isambard’s ambitions to extend to Holyhead and run an Irish Mail service.

He would, however, reach Ireland another way. On 4 August 1845, the South Wales Railway was approved by Parliament, and guess who was appointed engineer?

Plans to continue the Cheltenham & Great Western Union Railway from Gloucester to Fishguard via Chepstow were scuppered as it was refused permission to build a bridge across the tidal River Severn between Frampton-on-Severn and Awre because of Admiralty concerns about ships needing to pass beneath.

Work began in 1848, concentrating, because of financial restraints, on the 75-mile Swansea-Chepstow section, which included a 742-yard tunnel at Newport and huge timber viaducts at Landore (1760ft) and Newport. This section opened on 18 June 1850, with GWR operating the line, built to broad gauge and detached from the rest of the system.

It did, however, link up with the aforementioned 24-mile Taff Vale Railway, which had opened in 21 April 1841, and resisted attempts to convert it to broad gauge, although a mixed-gauge link line was built from the South Wales Railway’s Cardiff station to the Taff Vale at Bute Road.

The GWR then gained approval for a nominally independent Gloucester & Dean Forest Railway to link the South Wales Railway to the Cheltenham & Great Western Union Railway. This line, leased to the GWR, opened on 19 September 1851, but a bridge over the River Wye at Chepstow was needed to link it to the South Wales Railway.

Isambard provided a magnificent structure at a cost of £77,000. Its main 300ft span from a 100ft-high limestone cliff, supported by a 9ft-diameter overhead semicircular tube girder and cast-iron columns, filled with concrete and sunk in the bed of the river, was followed by three further 100ft spans, all of which stood at 50ft above the high-tide level.

It was a new type of bridge construction, a bespoke solution for a unique location, which typified Isambard’s genius and also ended up being a trial run for one of his greatest engineering feats, the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash, as we shall see.

Trains were able to run from Gloucester to Swansea for the first time on 18 April 1853. It brought Swansea to within six hours of London; the previous best was 15 hours, using stagecoach, a ferry and GWR from Bristol. The line, which used Gooch Firefly locomotives at the start, was extended from Landore near Swansea to Carmarthen on 11 October 1852, with a 789-yard tunnel at Cockett.

In 1844, Isambard had informed the Dublin & Kingstown Railway, the first in Ireland, of his intention to build a broad-gauge line to Fishguard and start a new sea route to Rosslare. His suggestion to help the DKR build a line to Wexford, led to the formation of the Waterford, Wexford, Wicklow & Dublin Railway, work finally beginning on the line from Dublin to Wicklow in August 1847.

By 10 July 1854, the line to Bray was opened. However, serious engineering problems were encountered on the line at Bray Head to the south, where the topography proved difficult for the building of a railway. The coastal route had been chosen because it offered spectacular scenery, unlike the more straightforward route inland.

Isambard used his experience from Thames Tunnel days to chisel through the hard rock and build three tunnels to carry the line, which reached Wicklow Town in 1855.

In Wales, Brunel never did reach Fishguard with his broad gauge and instead looked at the west coast of Pembrokeshire for an Irish terminal.

Pressing on, Haverfordwest was reached by the South Wales Railway on 2 January 1854, and Neyland – subsequently renamed Milford Haven and then New Milford – on 1 July 1857.

In the meantime, GWR helped other schemes to intensify the broad-gauge links to South Wales. The Hereford, Ross & Gloucester Railway linked with the Cheltenham & Great Western Union Railway at Grange Court at one end, and the standard gauge Shrewsbury & Hereford Railway at the other.

Several broad-gauge routes appeared in the Forest of Dean – then a hive of heavy industry because of its coal reserves. They included the Forest of Dean Railway, linking Cinderford to Bullo Cross on the Cheltenham & Great Western Union Railway, the horse-worked Severn & Wye Railway from Coleford to Lydney, the short Forest of Dean Central Railway from Brimspill to the Howbeach Valley.

Isambard was never short of work in South Wales. He engineered the broad-gauge Vale of Neath Railway, which opened between Neath and Aberdare on 24 September 1851, extending from Aberdare to Gelli Tarw, the junction for Merthyr Tydfil, on 2 November 1853. Excelling himself again, Isambard oversaw the construction of a 2495-yard tunnel at Merthyr, plus major viaducts at Merthyr and Werfa.

He also engineered the freight-only South Wales Mineral Railway, which ran from Briton Ferry along the Afan Valley to Glyncorrwg, and not only had 1-in-22 gradients and a 1109-yard tunnel at Glfylchi, but an ingenious rope-worked incline.

Isambard was engaged in 1851 to design and build a Bristol-style floating dock at Briton Ferry for the shipment of coal, and diverted the River Neath in order to provide a site for it. He built a half-mile broad-gauge extension to the Vale of Neath Railway to serve a wharf at Briton Ferry, opening in 1852, nine years before the dock was completed.

In the far west of Wales, the broad gauge pushed on, part of the Carmarthen Railway being built to 7ft 0¼in gauge for seven miles between Carmarthen and Convil (much of this section is now preserved as the Gwili Railway) and opening on 1 July 1860. Also, the four-mile Milford Railway, which ran between the South Wales Railway at Johnston and Milford Haven docks, was opened on 7 September 1873 and operated by the GWR.

The broad gauge in South Wales, however, did not work to the advantage of the GWR, which had more than a finger in the pie of all the railway schemes in the region that had adopted 7ft 0¼in.

The booming South Wales coalfield became a labyrinth of independent lines, mainly standard gauge, for conveying coal to docks. Because transhipment to broad-gauge wagons would incur extra labour costs and delays, it was not a preferred option, and comparatively little coal was conveyed on the Brunel system. Meanwhile, rival standard-gauge companies like the Midland Railway and London & North Western began extending into the region.

The GWR had to react to market pressures, in short, by the end of 1872, the entire route from Gloucester to Milford Haven had been converted to standard gauge, with the adjacent broad-gauge lines following suit.

In the meantime, GWR had also been expanding its interests in the south of England, either directly promoting new lines, or investing in and influencing them as independent but ‘satellite’ concerns.

The mid-1840s Railway Mania saw the 39-mile Berks & Hants Railway built, under Isambard’s auspices from the GWR main line at Reading to Hungerford via Newbury, opening on 21 December 1847, and from Southcote Junction to Basingstoke, opening on 1 November 1848.

Simultaneously, the Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth Railway, leaving Isambard’s original GWR main line at Thingley Junction near Chippenham, was opened in stages from 5 September 1848 to 20 January 1857, running via Yeovil and Dorchester. It had branches from Warminster to Salisbury and from Frome to Radstock, (the latter currently the subject of a protracted and stalled preservation scheme), and an offshoot, the Bridport Railway, from Maiden Newton to Bridport, opened on 12 November 1857, and eventually carrying on (after conversion to standard gauge) to West Bay.

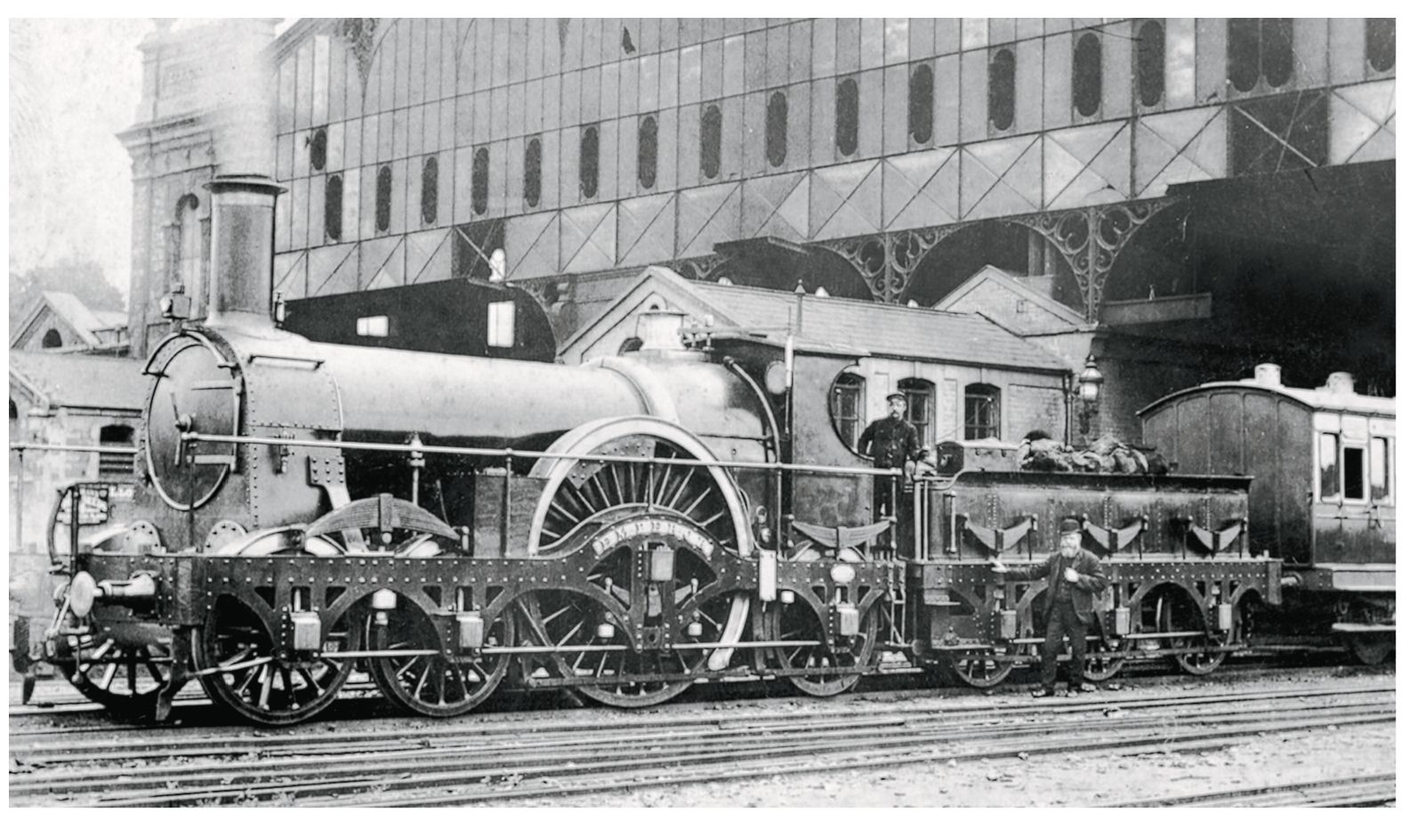

No 2123 Pluto was a South Devon Railway 4-4-0ST built by the Avonside Engine Company in October 1866. Atmospheric era aside, the South Devon had originally been worked by contractors and it was only in 1866 that the company started running its own services. This was one of the first batch of eight locomotives delivered to the company that year, six 4-4-0STs for passenger trains and two 0-6-0STs for goods workings. Pluto was one of the four passenger locomotives of this class that lasted until the end of the broad gauge in May 1892. It is seen here on an Up working double-heading a GWR Rover class 4-2-2. Broad gauge open and tilt wagons, both with tarpaulins, stand in the siding beyond.

A broad gauge train crossing a typical Brunel trestle viaduct of the type which were commonplace on his lines in Cornwall, South Devon and South Wales and allowed railways to be built across hilly terrain at affordable cost. The frequent use of such ‘cheaper’ structures greatly facilitated the expansion of the broad gauge empire. ELTON COLLECTION: IRONBRIDGE GORGE MUSEUM TRUST

The Somerset Central Railway between Highbridge and Glastonbury, engineered not by Brunel but by Charles Hutton Gregory, was opened on 17 August 1854 as a broad-gauge line worked by the Bristol & Exeter Railway, quickly extending to Wells and Burnham-on-Sea, but much to the anger of the GWR, was converted to mixed gauge after 1861 when the operator’s lease expired.

This line linked up with the standard-gauge Dorset Central Railway to form, on 1 September 1862, the Somerset & Dorset Railway.

The East Somerset Railway today is a preserved line based at Cranmore, near Shepton Mallet. It is, however, part of a much longer route opened from Witham on the Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth Railway to Shepton Mallet on 9 November 1858 as broad gauge, extending to Wells in 1862 and linking to the Bristol & Exeter’s Cheddar branch. The East Somerset was bought by the GWR in 1874.

The Exeter & Crediton Railway was built to broad gauge as it linked to the Bristol & Exeter, but when it was finished in 1847, the London & South Western Railway used its majority shareholding to insist it was converted to standard gauge. The Government’s Railway Commission ruled that was illegal, and the line was then leased to the BER. It connected to the North Devon Railway to Barnstaple, which was also broad gauge.

Following complaints that the BER was not managing the line properly, it was leased to the LSWR, which promptly installed mixed-gauge rails, and broad-gauge operations north of Crediton, where the Brunel station office survives today, ceased after 1877.

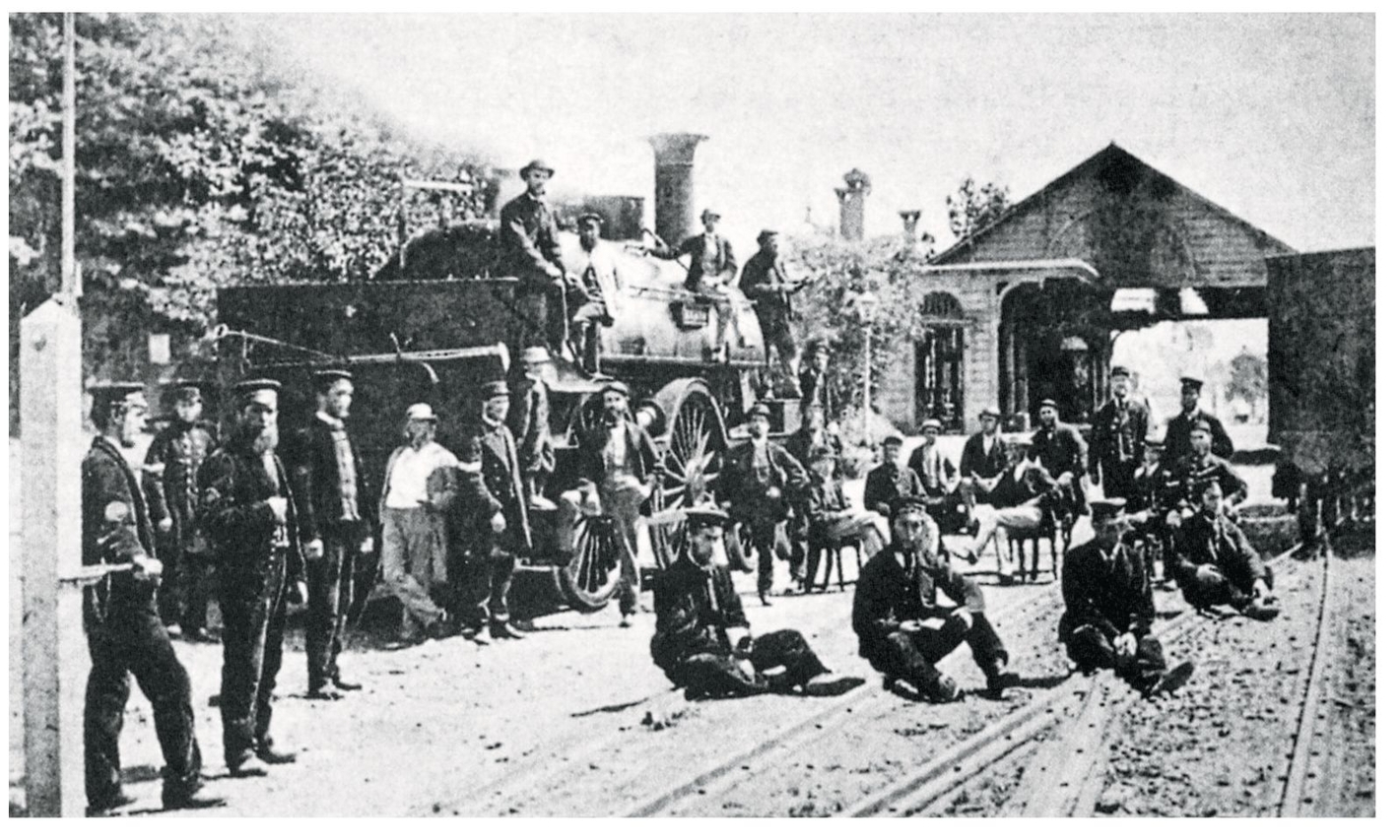

Torre station, pictured in 1870, was the place where the South Devon Railway’s Torquay branch net the Torbay & Dartmouth Railway, also engineered by Isambard Brunel, part of which today operates regular Great Western steam as the Paignton & Dartmouth Steam Railway. The passenger locomotive in the picture is Avonside Engine company 4-4-0 Zebra, which became GWR No 2127. Torre remains an excellent example of a Brunel station, but Isambard surveyed more than just railways at Torbay. He bought 136 acres of land at Watcombe and designed a house in which he wanted to live with his family, surrounded by landscape gardens and an arboretum, but he completed only the foundations before he died. The completed Brunel Manor House is now run by the Woodlands House of Prayer Trust as a Christian holiday and conference centre. BROAD GAUGE SOCIETY

Exeter St David’s was not only the terminus of the Bristol & Exeter Railway, but the gateway to Brunel’s expanding west of England empire. GWR 4-2-2 Emperor stands at Exeter in 1889. GW TRUST COLLECTION

Meanwhile, another broad-gauge line reached Barnstaple in the form of the Devon & Somerset Railway from Taunton, which was worked by the BER but was not formally taken over by the GWR until 1901.

There were other smaller concerns. In 1857, Royal Assent was given for the broad gauge Dartmouth & Torbay Railway, with Isambard as engineer. Opening at the beginning of August it effectively extended the South Devon Railway, which operated the line, from its Torquay station at Torre to Kingswear, opposite Dartmouth, which was reached by means of a floating bridge or road-vehicle ferry, as it still is today. A typical station booking office building at Dartmouth was opened in 1889 – but it has never been physically served by trains, and as such acquired a unique status on the national network. It survives today on the waterfront as a cafe.

In 1862, an Act of Parliament passed for the construction of a broad-gauge branch line from Moretonhampstead to Newton Abbot, the route opening as the Moretonhampstead & South Devon Railway on 26 June 1862. The line was absorbed in 1872 by the South Devon Railway which in turn became part of the GWR empire.

It was not the last broad-gauge line to be built, but by then the writing for the 7ft 0¼in gauge was on the wall.

Did Brunel ever think that, in the face of opposition from the likes of leading authorities like Stephenson, his broad gauge, while superior in so many respects, would ever be adopted as the norm throughout Britain, or did he envisage a super-efficient regional service serving just part of it, with passengers and goods being switched to the smaller trains of other companies wherever the ‘break of gauge occurred’?

Had his system ‘got in first’, and had been adopted by main line railways everywhere, how different would our national transport network be today.

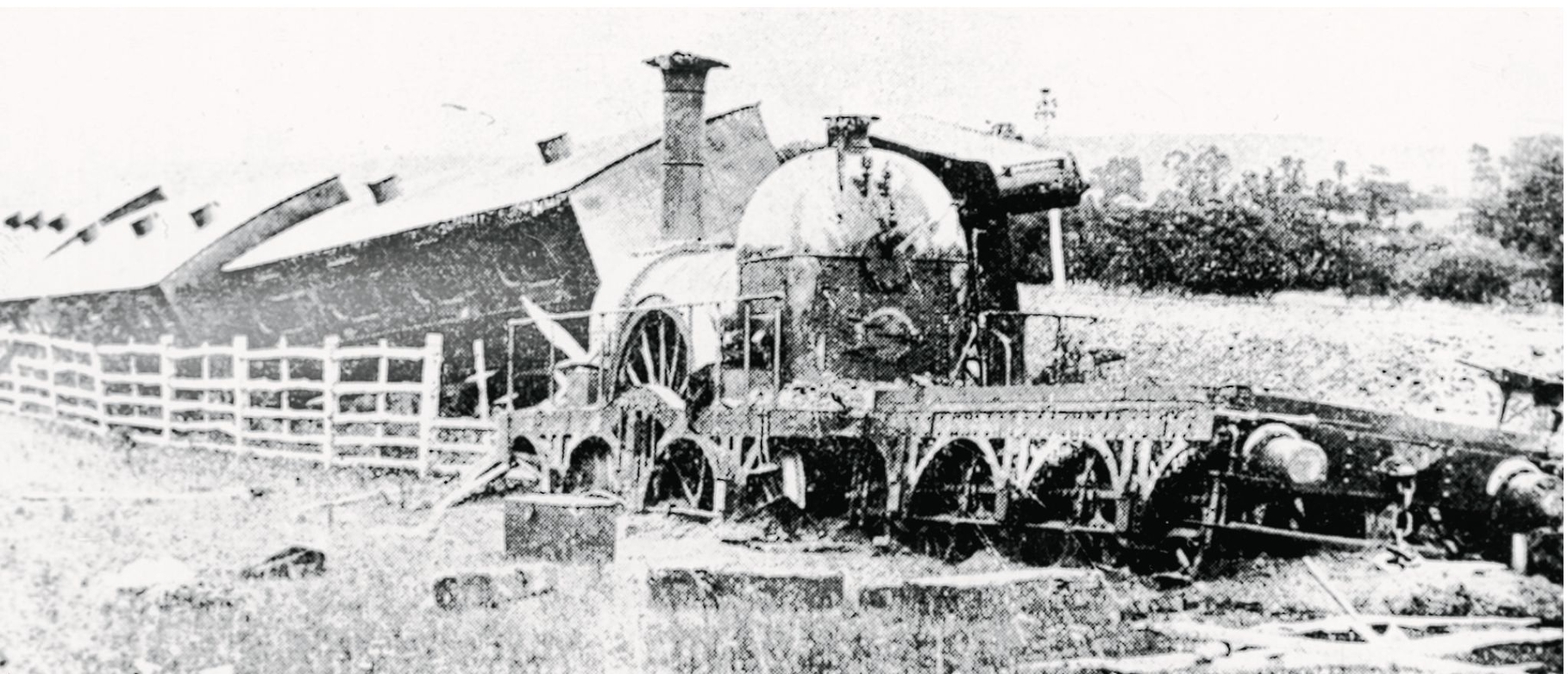

Firefly class 2-2-2 Load Star and its express train came unstuck at Carmarthen while hauling the 9.15am from Haverfordwest on 8 January 1855. GW TRUST