Chapter 16

GO GREAT WESTERN – TO NEW YORK

The First Transatlantic Liners

While the new breed of steam-railway magnates was busy carving up Britain, the eyes of Isambard Brunel were already set on a far greater goal.

He wanted to extend his Great Western Railway from London, beyond Bristol – all the way to the United States.

At one stage in his career, Brunel had been touring the country touting for work. Soon, there would come a day when he would become the ultimate workaholic – tackling not one, but several world-beating projects back-to-back.

While he was overseeing the building of the GWR, a project that in itself would have placed him among the greatest engineers of all time; he was busy working on a new and very different project of monumental proportions – the world’s first transatlantic liners.

Shipping was the last major area to benefit from the massive strides in transport technology, which had been spawned by the Industrial Revolution, and in the 1830s, still owed more to traditional building techniques than the application of modern science.

Just as railways had been the preserve of horsepower until the Rainhill Trials of 1829, so shipping had been based on developments of sail power, with the industry slow to take up the new steam technology.

What Richard Trevithick was to steam-powered road and rail locomotives, William Symington was to steamboats.

Symington was born in Leadhills, Lanarkshire, in 1764, the son of a mechanic who worked the local lead mines, and like Trevithick, became a pioneer in steam mining technology.

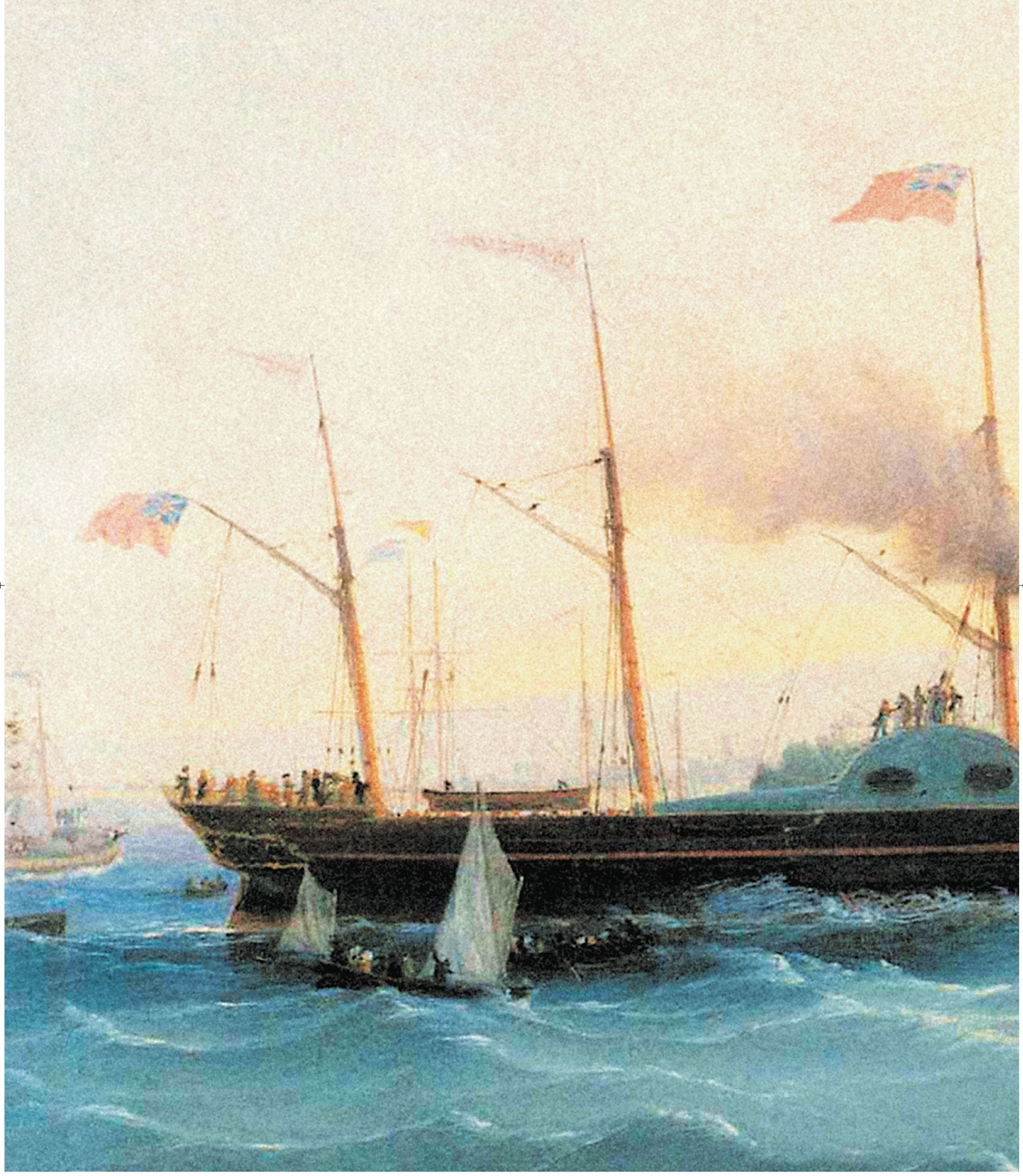

The Great Western in the Bristol Channel off Portishead, after leaving the safety of the Avon estuary on her first transatlantic voyage, as seen in a contemporary Joseph Walter oil painting. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

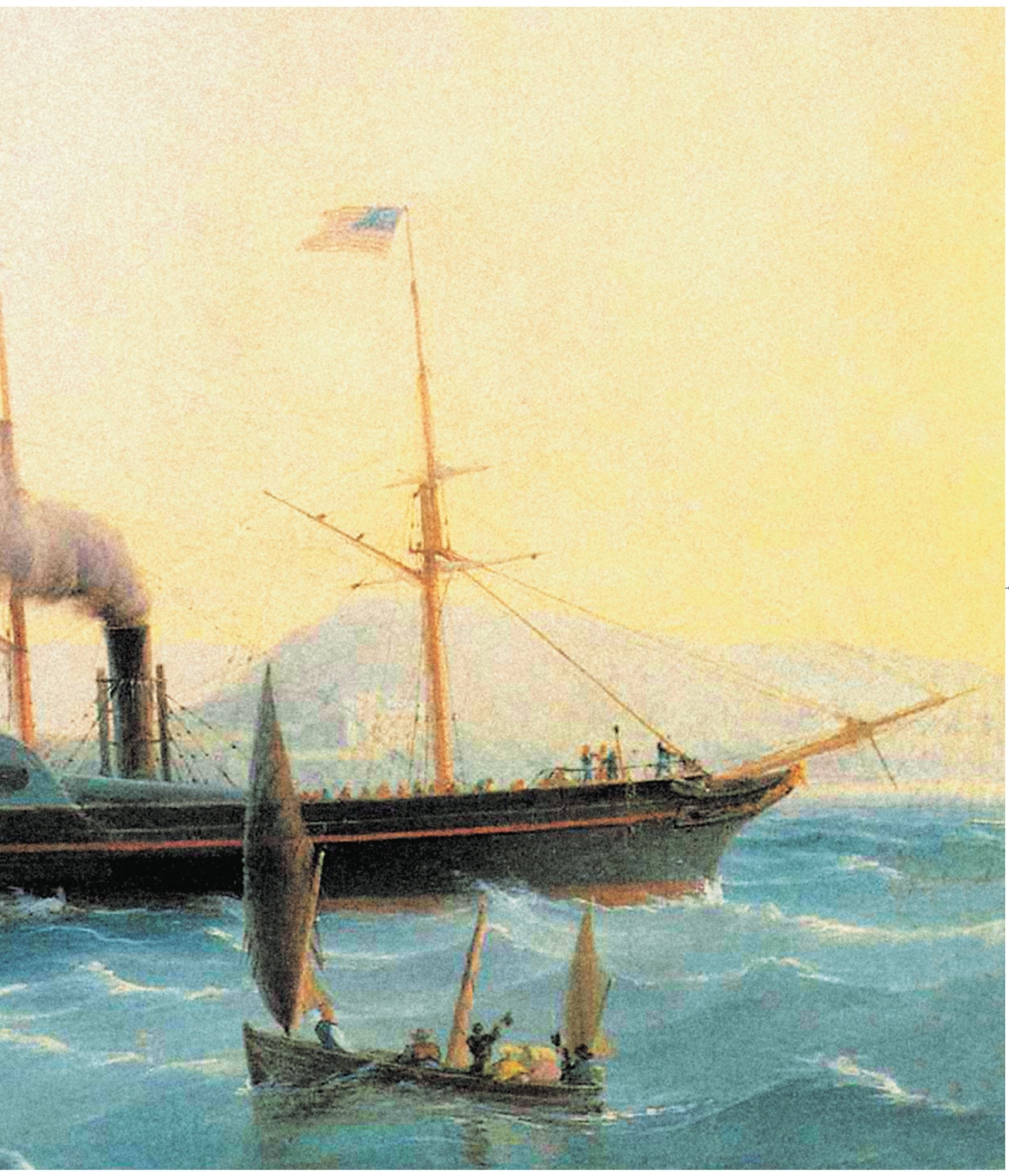

Standing room only, on another day when Brunel changed the world: Bristol’s waterfront was packed out on 19 July 1843, when the SS Great Britain was floated for the first time, as seen in this Joseph Walter engraving.

Having worked on perfecting one of James Watt’s stationary steam engines, Symington was approached by Patrick Miller, banker and shareholder in Carron Company, Scotland’s premier engineering firm, to fit a steam engine inside a pleasure boat for small-scale trials. The aim of this early experiment was to demonstrate that an engine could work on the unstable foundation of a boat, and would not set it on fire.

The engine had already been demonstrated on a model steam carriage, which Symington had built in 1785. The partly successful trial took place on the loch next to Miller’s house at Dalswinton, near Dumfries, on 14 October 1788.

Miller was so impressed he ordered a larger engine to undergo tests in a paddleboat on the Forth and Clyde Canal on 2 December 1789 and, after several trials, it reached a speed of nearly 7mph.

Thomas, Lord Dundas, governor of the Forth and Clyde Canal Company, looked into the possibility of using steam tugs along the lines of a prototype trialled by Captain John Schank on the Bridgewater Canal, near Manchester in 1799.

He asked for a Symington engine to be added to a Schank-designed boat, which was successfully given a run-out on the River Carron in June 1801, but was ruled unsuitable for the canal. Symington patented a horizontal engine in 1801, which was more powerful, and won the support of Lord Dundas for a second vessel – to be named Charlotte Dundas, after one of his daughters – to be built.

It was launched in Glasgow on 4 January 1803 and after some later modifications, towed two loaded vessels along the canal, covering 18½ miles in nine-and-a-quarter hours.

Sadly, the canal company turned it down, because of fears it would damage the navigation’s banks, and it was forced to live out its life in one of the waterway’s passing bays.

Symington, like Trevithick, ended his days fraught with financial difficulties, but nonetheless, his Charlotte Dundas had staked its claim to being the world’s first viable steamship.

The launch in 1812 of Henry Bell’s Comet on the Clyde – the first steam-operated commercial ferry, was followed two years later by the steamboat Regent, plying its trade between London and Margate. Its designer? Marc Brunel, who again showed he was more than up to speed with cutting-edge technology.

The first cross-channel steamship was the 112-ton Hibernia, which made it from Holyhead to Dublin in seven hours in 1816. The first oceanic crossing by a steamship was made in 1819 by the PS Savannah, built by Francis Fickett, of Corlears Hook, New York; with an engine provided by Stephen Vail of the Speedwell Iron Works, New Jersey.

Originally intended for the sail packet service to Le Havre, it set out from Savannah, Georgia, reaching Liverpool on 20 June, after 29 days 11 hours. However, the engines were sparingly used and for the most part, the ship relied on its sails.

Up to 1835, steamships were still considered suitable only for short runs in comparatively shallow waters, as the early examples did not have the capacity to carry and burn sufficient coal for anything like a transatlantic voyage.

It was considered by leading authorities, including Marc Brunel, that the consumption of coal by a steam engine would increase in proportion to the size of a ship, and if the existing vessels could not manage to cross an ocean, logic dictated that neither could a larger one.

It needed a genius to rewrite the principles of the ‘logic’ of the day, someone who had already showed himself capable of doing just that.

Isambard realised that this principle was erroneous, as the energy needed to drive a ship, whether by sail or steam, did not depend on the vessel’s weight, but on the weight of the water that it had to shift.

He worked out that the key factors were the surface area of the ship, and its shape, and found that contrary to previous belief, the larger the vessel; the more favourable the crucial energy-to-weight equation would be.

At an early meeting of the GWR board, Isambard was said to have suggested extending the railway by adding a steamboat – to be called the Great Western, after the company – and which would go all the way to New York.

One of the directors, Thomas Guppy, did not join in with the ensuing scorn, and persuaded three other board members, Robert Scot, Robert Bright and Thomas Pycroft to set up a committee to look into the possibility. They were joined by naval captain Christopher Claxton, who Brunel had met while working on the improvements to the city docks, and who was able to gain access to official drawings of Admiralty vessels currently under construction.

A low-key prospectus called for the company to build not one, but two, 1200-ton steamships with 400-horsepower engines. Many local people bought shares in the scheme, including Isambard.

A new prospectus was issued before the first meeting of a new Great Western Steamship Company on 3 March 1836, giving further details of the proposed ships and the estimated cost of £35,000 each. Five of the directors were also board members of the GWR.

Isambard roped in Bristol shipbuilder William Patterson to add his weight and expertise to the project. It was inside Patterson’s yard at Wapping Wharf, in the Floating Harbour, that the keel of the first ship was laid in June that year, without pomp or ceremony. At 205ft, it was the longest ever to have been laid.

The ship was clearly so huge that sceptics were again at the fore, doubting whether it could ever be brought out of the dock and down the winding mud of the Avon Gorge to the Bristol Channel, let alone set out to sea.

Lambeth manufacturer Maudslay, Son & Field had vast experience in building marine engines and was selected to supply the ship’s engines, which had massive cylinders with a 73½in diameter and a stroke of 7ft, and were to drive twin-paddle wheels 28ft in diameter.

The Floating Harbour with the Avon Gorge and Isambard Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge in the background. Two ships he designed and which were destined to change the world left Bristol through here. BRUNEL 200

The great day came on 19 July 1837, when more than 50,000 onlookers crowded into Bristol’s docks and on to adjacent vessels to watch the ship’s launch.

As the ship started moving down the shipway, a deafening cry of ‘She moves!’ soared to the sky, as Claxton smashed a bottle of madeira over the bowsprit.

Mrs Miles, wife of one of the steamship company’s directors, named the ship the Great Western. Afterwards, 300 invited guests joined the directors for dinner in the ship’s main cabin.

On 18 August, the Great Western was towed down the Avon estuary by the steam tug Lion, and, accompanied by the steam packet Ben Ledi, using a four-masted schooner rig to travel to London around the south coast of England as a sailing ship.

The London crowds were equally ecstatic when they glimpsed the Great Western for the first time, if only for her sheer size.

In East India Dock at Blackwall, much of the machinery was fitted by Maudslay over an intensive six-month period, and in March 1838, the Great Western was moved to a berth in the River Thames for preliminary trials, during which the ship struck another vessel and days later became briefly stuck on a mud bank opposite Trinity Wharf.

However, four days of engine trials saw the Great Western comfortably manage an average speed of 11 knots.

Isambard had again silenced his critics, including a Dr Dionysius Lardner, who had publicly proclaimed in 1835 that transatlantic steamship travel was all but impossible, discouraging would-be investors from the steamship company.

But, in the cut-throat world of business, being proved right counts for nothing if others are quicker to take up on your innovations than you are.

North Atlantic shipping companies in both London and Liverpool had watched the coming together of the Great Western with immense interest, and as it entered its final stages of completion, began to convert existing ships in order that they could compete with her.

The British & American Steam Navigation Company’s new vessel, the British Queen, would not pip the Great Western to the post as regards making a maiden voyage, and so the firm hired another ship, the 703-ton Sirius, with which it intended to make the first scheduled steamship crossing to the United States. The Sirius set out with 22 passengers in March 1838, while the engines on the Great Western were still being tested.

At last, on 31 March, the Great Western set off for Bristol with Isambard on board to collect the passengers for her maiden voyage. However, around noon, with the ship moving down the Thames, flames and smoke began pouring from the engine room. The boiler lagging had become too hot and caught fire.

The ship’s captain, Lieut Hosken, grounded the Great Western on soft mud while the fire was extinguished, but Isambard, descending a ladder to the boiler room, stepped on a burned rung and fell 20ft, badly injuring himself.

The Great Western arrived in Bristol on 2 April, only to find that many of the passengers had cancelled their bookings because of rumours, which had spread about the ship’s ‘failings’.

With just seven passengers on board, the Great Western set out in pursuit of the Sirius on 7 April. It arrived in New York at noon on 23 April, having made the crossing in just 17 days – only to see the Sirius, which had run aground there the previous night, after exhausting almost all of its coal supply – already moored there.

The Americans were enthralled by the race between the two ships, and so many people wanted to board the Great Western that the captain was forced to issue tickets in order to control numbers. On the return journey, the Great Western reached Britain in just 14 days, as compared to the 18 taken by her rival, and proved that unlike its competitor, it could cross the Atlantic with passengers and cargo and still have coal to spare.

The Great Western proved to be another world-beater for Isambard, and was an immediate commercial success, making 67 crossings in eight years and silencing her critics for good.

However, she could not fit through the lock gates leading into the Floating Harbour, and accrued high mooring charges by having to be moored in King’s Road in the Bristol Channel.

When it left Bristol for New York on 11 February 1843, it would be the last departure of a transatlantic liner from the port for 28 years. In turn, Bristol’s importance as a port for Atlantic trade went into decline, and all because the harbour authorities refused to widen the lock gates for new, bigger ships to pass.

Taken out of service at Liverpool in 1846, the Great Western was sold to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company and used on voyages to the Gulf of Mexico for 10 years, after which she ended her days as a troop ship during the Crimean War, before being scrapped in 1857.

Never one to take a well-deserved rest, in September 1838, Isambard and his committee began planning their second ship.

Initial thoughts by Isambard, Guppy and Claxton turned to a bigger 254ft-long oak ship with even bigger paddle wheels, but they were stopped in their tracks when an iron-hulled paddle steamer, the Rainbow, docked in Bristol. Claxton and Paterson sailed in the ship to Antwerp to record her performance.

The first iron-hulled vessel had appeared in 1787, a 70ft-long canal barge, built by John ‘Iron Mad’ Wilkinson, a partner in the successful project to build the world’s first iron bridge over the Severn Gorge, and who, on his death in 1808, was buried in his native Cumberland in an iron coffin.

Medium-sized ocean-going iron-hulled ships were being produced in Britain in the 1820s, and had the advantage of being 30 per cent lighter than their wooden counterparts. The first iron steamship, the Aaron Derby, was built in 1821, but was on nowhere near the scale proposed by Isambard for the company’s second ship.

The Brunel committee sat down to work, and between September 1838 and June the following year, six different designs were produced. Eventually chosen was Isambard’s ‘box-girder’ type hull with a two-skinned cellular construction, having six watertight compartments and two longitudinal bulkheads, plus a strong iron deck.

The keel for the new vessel, nicknamed the ‘Mammoth’ was laid on 19 July 1839, again in Patterson’s yard.

Isambard was captivated by the sight of the world’s first propeller-driven ship, Francis Pettit Smith’s Archimedes, when it arrived in the Floating Harbour in May 1840, and Guppy took a trip to Liverpool aboard her.

His report impressed the steamship company to the extent that they ordered all work on the paddle steamers for their second vessel to stop, and booked the Archimedes for six months of tests.

Isambard saw that a fully immersed propeller would be far more efficient than paddle wheels, and in December 1840 insisted that the new ship should be driven exclusively by one.

The decision delivered a fatal blow to ambitious young engineer, Francis Humphrys, who had been chosen by the directors above Maudslay (and against Isambard’s advice) to build what would have been the world’s biggest marine engine for the ship as originally planned. Told to redesign the paddle engines, which were already at an advanced stage, he resigned and died of a ‘brain fever’ a few days after his work was halted.

Without an engine for the new ship, the project was delayed for two years while Brunel and Smith carried out more research into propellers. During this time, they designed an 800-ton experimental sloop, the Rattler, for the Navy. During a tug-of-war contest in April 1845, when attached to the Alecto, a paddle-driven vessel of similar size, the Rattler towed it backwards at a speed of more than two knots. Isambard had backed the winning horse yet again.

With Humphrys gone, Isambard designed the 1600-horsepower engines himself, based on the triangle type patented by his father. The company had leased land next to the Floating Harbour and developed the site into the world’s first integrated steamship works, building the engines inside.

The cost of the project soared, ending up at £125,555 – double that of the Great Western, but, buoyed by the success of his GWR, Isambard’s project managed to attract sufficient investors.

The ship was launched on 19 July 1843, exactly six years after that of the Great Western.

Prince Albert, arrived from London via the GWR on a special train driven by Daniel Gooch to take his place as guest of honour, after being greeted by the Lord Mayor at Temple Meads station.

Marc and Sophia Brunel watched proudly as the dry dock was flooded to allow their son’s giant creation to float.

Mrs Miles was again brought forward to name the ship, but the bottle of champagne missed its target. Prince Albert stepped forward to complete the job and smash a second bottle on the bow, naming the ship the SS Great Britain – a flagship for a country in a world it was beginning to dominate through its empire.

After the ceremony, the SS Great Britain was moved back into the dry dock for fitting out. She was ready in March 1844, but then it was discovered that she was too big to pass through the locks, which linked the Floating Harbour to the Avon estuary.

Isambard was the dock company’s consulting engineer, and persuaded its directors to allow modifications to be made to allow the SS Great Britain to pass the Junction Lock into Cumberland Basin, which it did on 26 October 1844, after a delicate and daunting day-long operation.

Trials were undertaken in the Bristol Channel on 12 December and 10 and 20 January before the SS Great Britain made a 40-hour voyage to London on 23 January, averaging 12½ knots, despite bad weather.

She was moored on the Thames for five months; Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were given a guided tour of the ship on 22 April 1845. With a displacement of 3675 tons, compared to 2300 for the Great Western, the SS Great Britain was the biggest ship in the world.

Its first Atlantic crossing was made from Liverpool on 26 July, carrying only 45 passengers and arriving in New York just 15 days later at an average speed of more than nine knots. During her second trip to the USA, the SS Great Britain sustained damage to the propeller and returned to Liverpool under sail power only, but still in only 20 days.

The SS Great Britain in 1846 en route to New York as painted by Joseph Walter. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

A four-bladed propeller replaced Isambard’s experimental six-bladed version, and a third voyage was made to New York on 29 May 1846. On the homeward journey, the SS Great Britain made the crossing in just 13 days, at an average speed of 13 knots.

The ship’s fifth trip, however, was an unmitigated disaster. With 180 passengers on board, it ran aground in Dundrum Bay in Ireland, on 22 September, with Captain Hosken, claiming his instruments had been affected by the iron hull and leading him to believe that he was off the coast of the Isle of Man.

There were no fatalities, and while the ship had been holed in two places, its strength prevented it from breaking up.

Claxton built a succession of two breakwaters around the beached ship to protect her, but to no avail, and with the finances of the steamship company also sailing close to the wind, Isambard finally went out to Ireland, to order a protective barrier of 5000 faggots to be piled against the side of the ship, which faced the sea.

After many efforts, the SS Great Britain was finally towed off the beach, by HMS Birkenhead on 27 August 1847.

However, its owners could not afford the £22,000 repairs on top of the £12,670 towing charge, and auctioned off all of her fixtures and fittings before finally selling her to Liverpool shipping firm Bright, Gibbs & Co for a knockdown £18,000.

The Great Western Steamship Company was wound up in February 1852 and the lease on its dockyard sold to Patterson.

New engines were installed for the Great Western’s comeback voyage in May 1852, after which the ship spent 24 successful years working the route to Australia. In 1876 she was bought by Antony Gibbs, Sons & Co for use as a transatlantic cargo sailing ship.

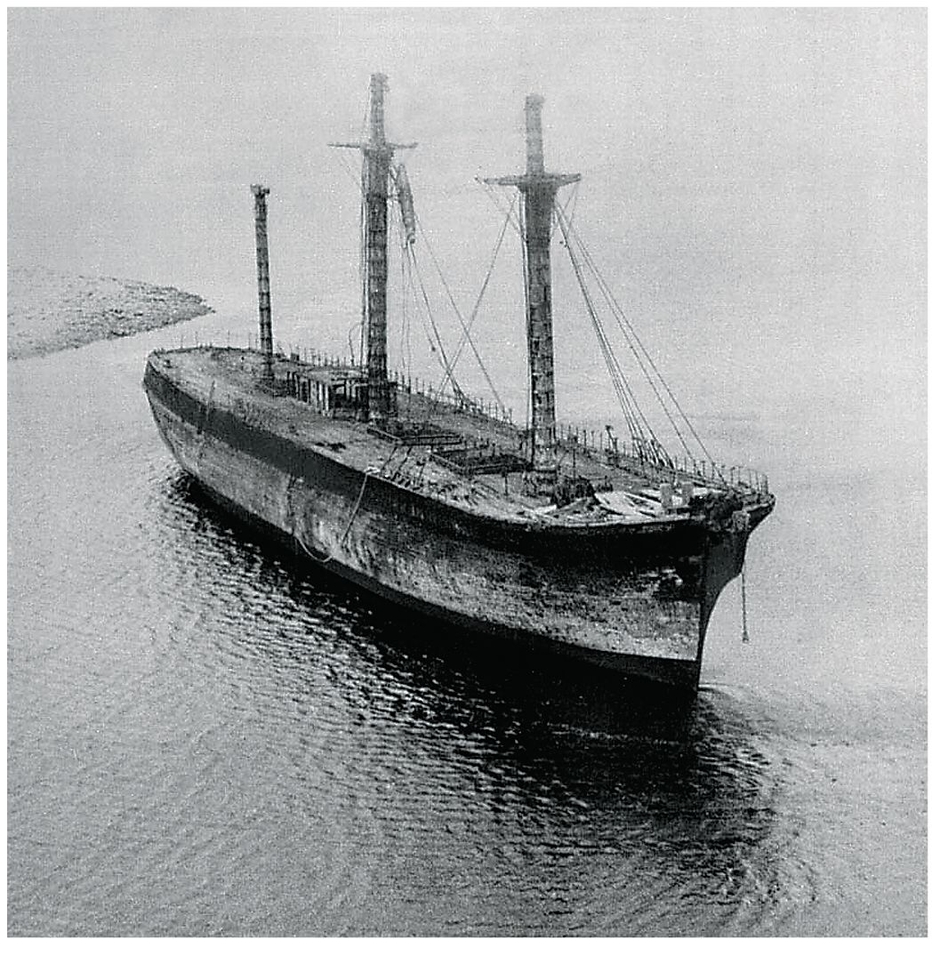

After difficulties rounding Cape Horn in April 1886, during which two masts were lost and severe leaks sprung, shelter was sought at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

Estimates for repairs proved too costly, and the ship was sold to the Falkland Islands Company as a store ship for coal and wood.

In 1937, the SS Great Britain was towed out of the harbour and beached at Sparrow Cove, with holes knocked in her stern to ensure that she would never float again.

Thankfully, that was not the end of the story.

The pioneers of transport preservation have made great advances in the post-war decades, not only in the fields of railway and canal heritage and the saving of historic aircraft, but also in shipping.

Interest in saving the SS Great Britain started in the USA and England during the 1950s, and in 1968, a naval architect visited the Falklands to see if it was possible to refloat her.

It was indeed possible, with the aid of a pontoon submerged beneath her hull. With the pontoon pumped out, the ship lifted on top of it.

The SS Great Britain was able to make one last voyage atop the pontoon, making the 7000 miles home, towed behind the salvage tug Varius II.

The journey began on 24 April 1970, via Montevideo, and took until 22 June, when they arrived off the Welsh coast, where Bristol tugs were waiting to take the pontoon into the docks at Avonmouth.

The SS Great Britain received a hero’s welcome in the port, and soon after, was lifted off the pontoon in the graving dock.

Finally, on 5 July, thousands of spectators again lined the banks of the Avon estuary as the ship, now afloat in its own right, was towed upstream to Bristol’s docks. She waited a fortnight for a spring tide high enough to allow her to be eased into the Great Western dry dock off the Floating Harbour.

The date was 19 July, 127 years to the day that she was launched in 1843.

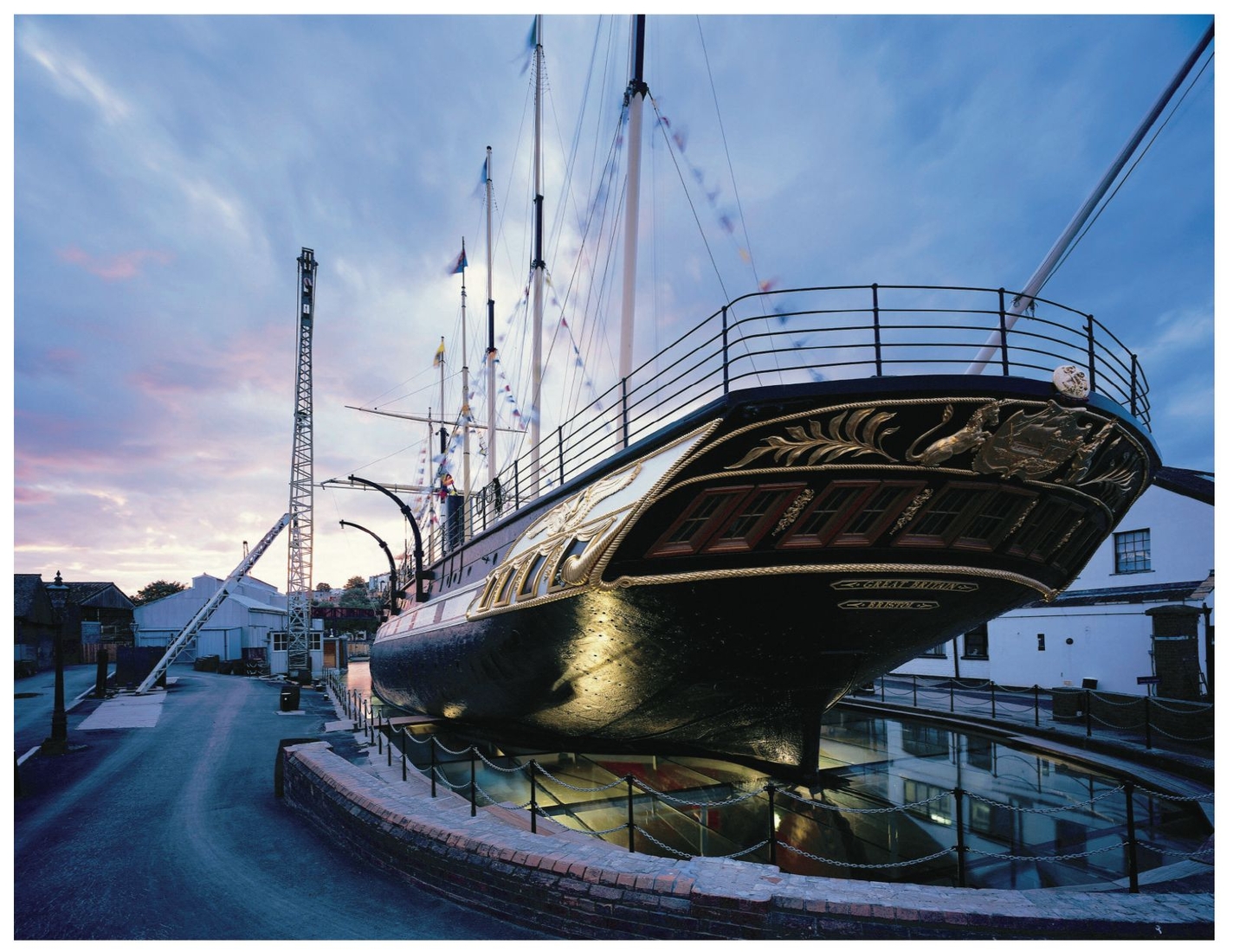

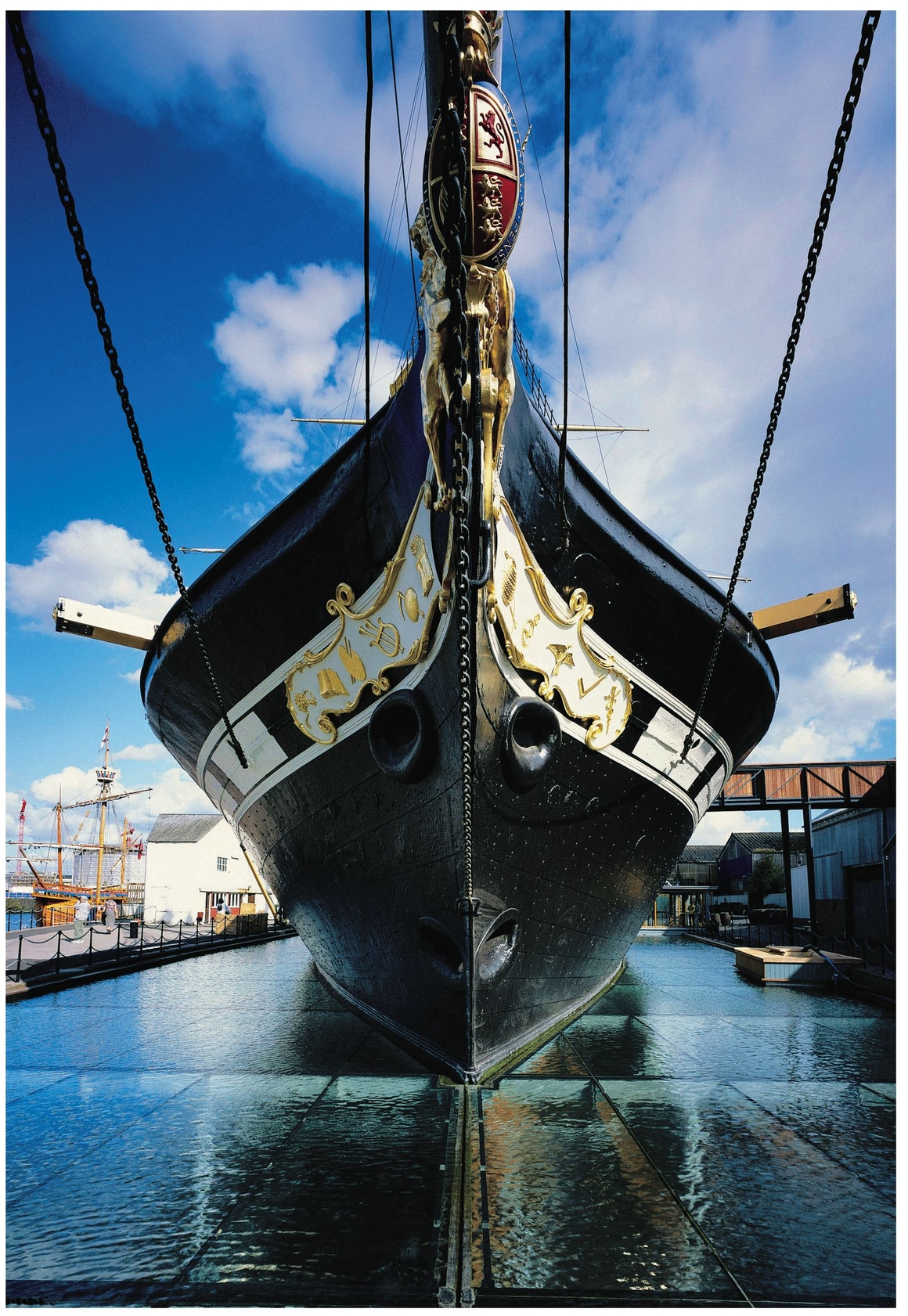

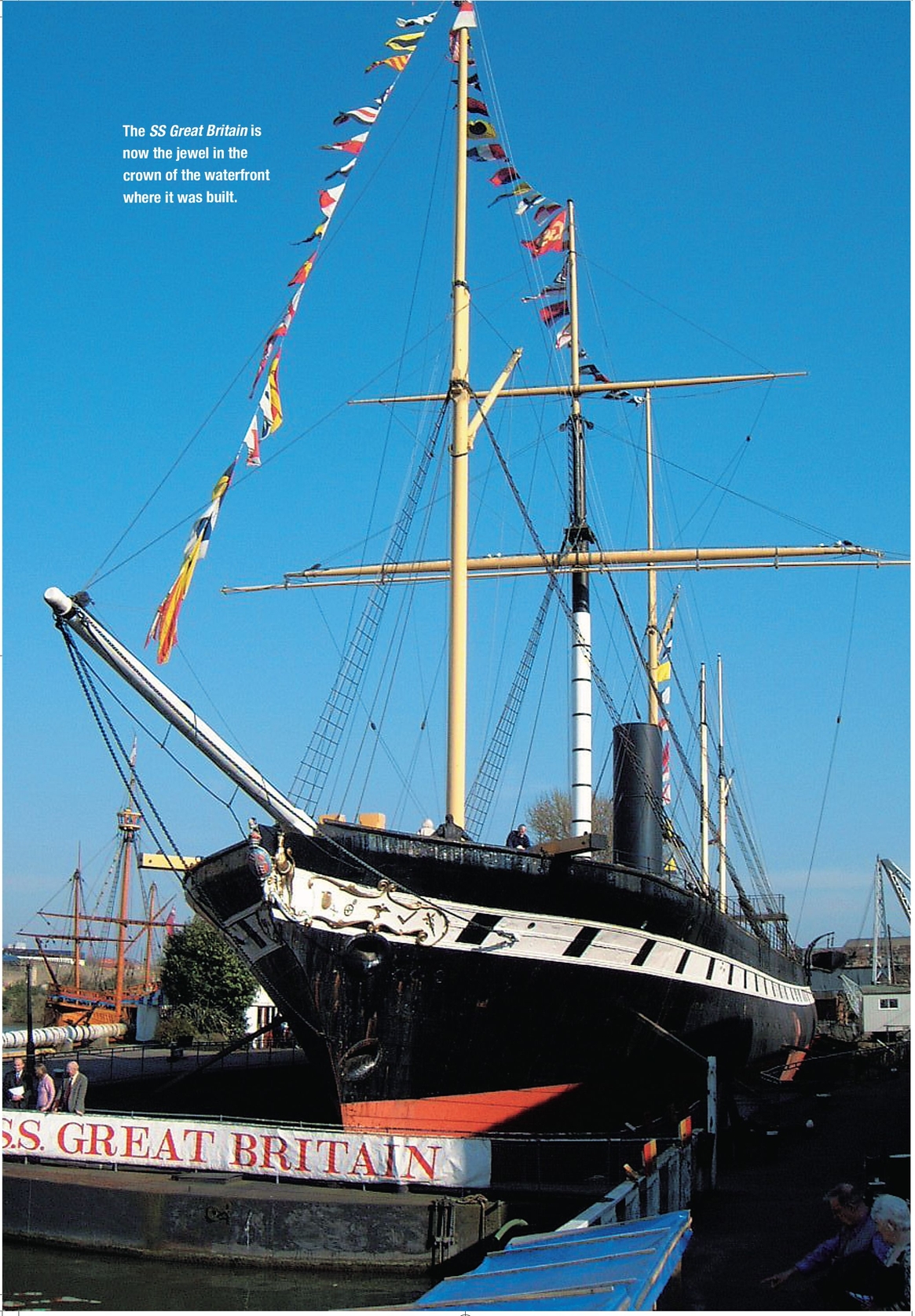

The meticulous restoration of the SS Great Britain, which is now recognised as having begun a revolution in international shipping, took 35 years to complete, and it is now a major attraction for tourists who come to see her in dry dock on one of the world’s greatest waterfronts.

The construction of a ‘glass sea’ at the waterline of the restored ship acts as a giant airtight chamber protecting its lower hull. Beneath the glass plate, moisture is removed from the air using special dehumidification equipment, preventing further corrosion of the hull. What was once the world’s biggest ship is now encased in one of the world’s biggest display cases.

The SS Great Britain after being refloated in Sparrow Cove on the Falkland Islands. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

One of Bristol’s real – and mostly overlooked – architectural treasures is the surviving face of what was built as the Royal Western Hotel, designed by RS Pope and Isambard Brunel and finished in 1839. It was intended to provide a luxury stopover for passengers who had arrived in London via his railway, and were to travel onwards to New York by liner. However, it closed down as early as 1855, and the bulk of the building behind the façade was later demolished to make way for modern offices, which now house a city council department. ROBIN JONES

The stern of the SS Great Britain, as displayed above its 21st-century ‘glass sea’. MANDY REYNOLDS

The bow of the SS Great Britain in its permanent Bristol home. MANDY REYNOLDS

The newly gilded SS Great Britain in its permanent Bristol dock. BRUNEL 200

The ‘glass sea’ is covered with a thin layer of water, so the ship appears to be floating. However, visitors can descend beneath the glass to see the ship’s hull and its key component, the propeller.

It will now stay moored in the dry dock, as a lasting monument to a man who shrank the world with his vision of transatlantic travel.

Memorial picture of Isambard Kingdom Brunel in the Illustrated London News. BRUNEL 200