Chapter 17

HOW THE WEST WAS FINALLY WON

The Bridge at Saltash and Beyond

In 814AD, the Saxons under Egbert conquered Cornwall, the last Celtic kingdom in the south-west, although he left the native rules in place. A century later, King Alfred’s grandson, Athelstan, made an all-out effort to bring Cornwall under English rule, but it would not be so easily tamed.

The River Tamar remained, for the most part, not only a great physical divide but a psychological and cultural one too. Cornishmen often thought of their homeland as a separate country, referring to Devon as ‘England’.

Nine hundred years later, the Tamar remained the last frontier for the great transport pioneers to conquer in order to bring the railway into the Duchy, where it would serve the mineral-rich mining areas and convey their products to markets far and wide.

The word Tamar is far older than English or Cornish. It has its roots in the ancient Sanskrit word for dark, which also presents itself in other British river names such as Tame, Teme, Thame, and Thames.

Just as Isambard had conquered the Thames with bridges everyone who knew better said would never stand up, so he was to accomplish what nobody else had ever believed possible – master the Tamar at its widest point.

Before the mid-19th century, the lowest crossing of the river was at New Bridge at Gunnislake, a local mining town. It was by then not so new, having been built in 1520 to carry the road from Callington to Tavistock.

If you wanted to cross below this point, such as from Plymouth to Torpoint or Saltash, boat was the only way. Until Isambard Brunel appeared, with his determination to turn one of his greatest dreams into reality – to run a railway from Paddington to Penzance.

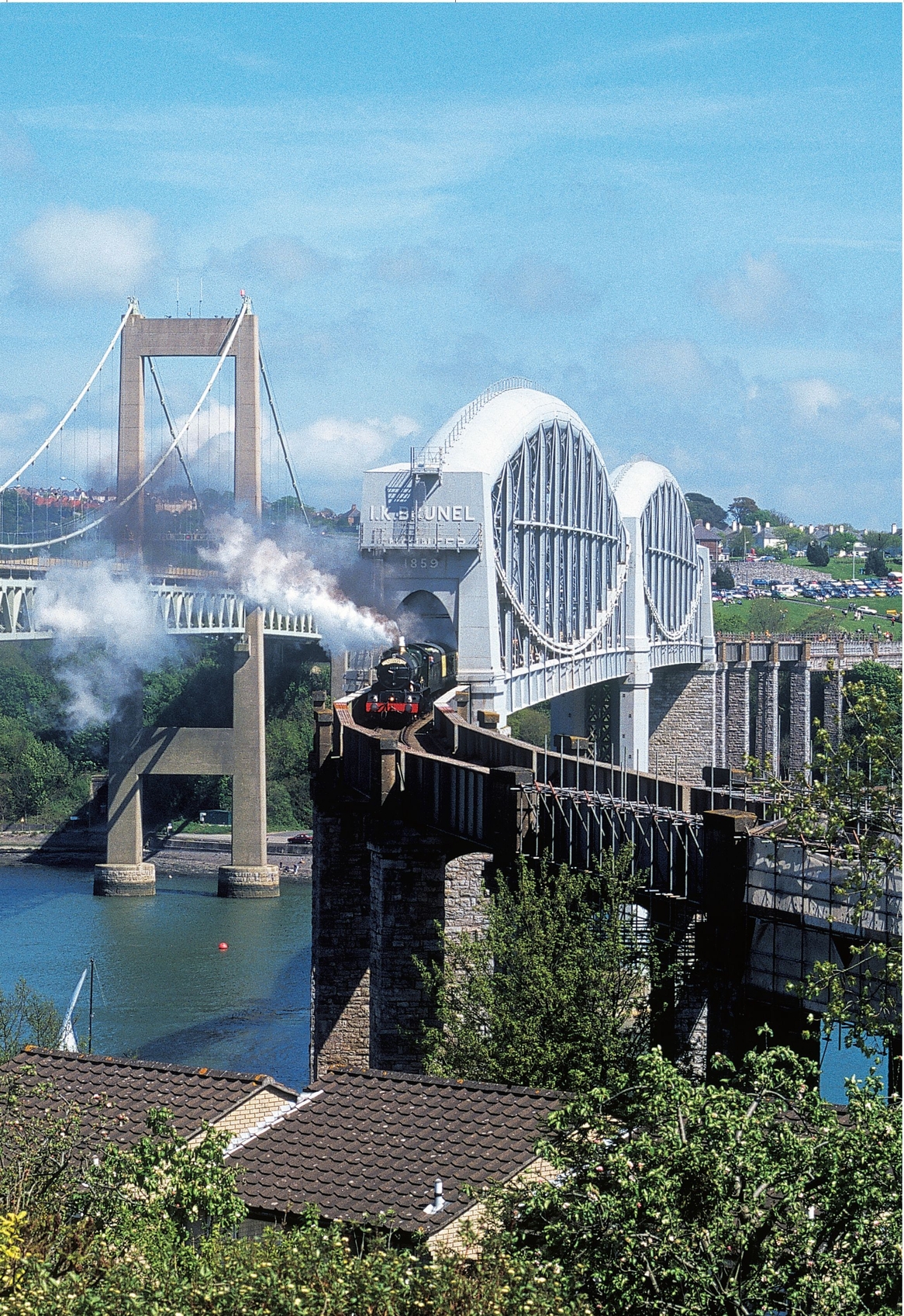

GWR express passenger 4-6-0 No 6024 King Edward I made what was claimed to be the first journey into Cornwall by a member of the company’s flagship locomotive class – hitherto banned because of weight restrictions – when it ventured over the Royal Saltash Bridge on 9 May 1998. ADRIAN KNOWLES

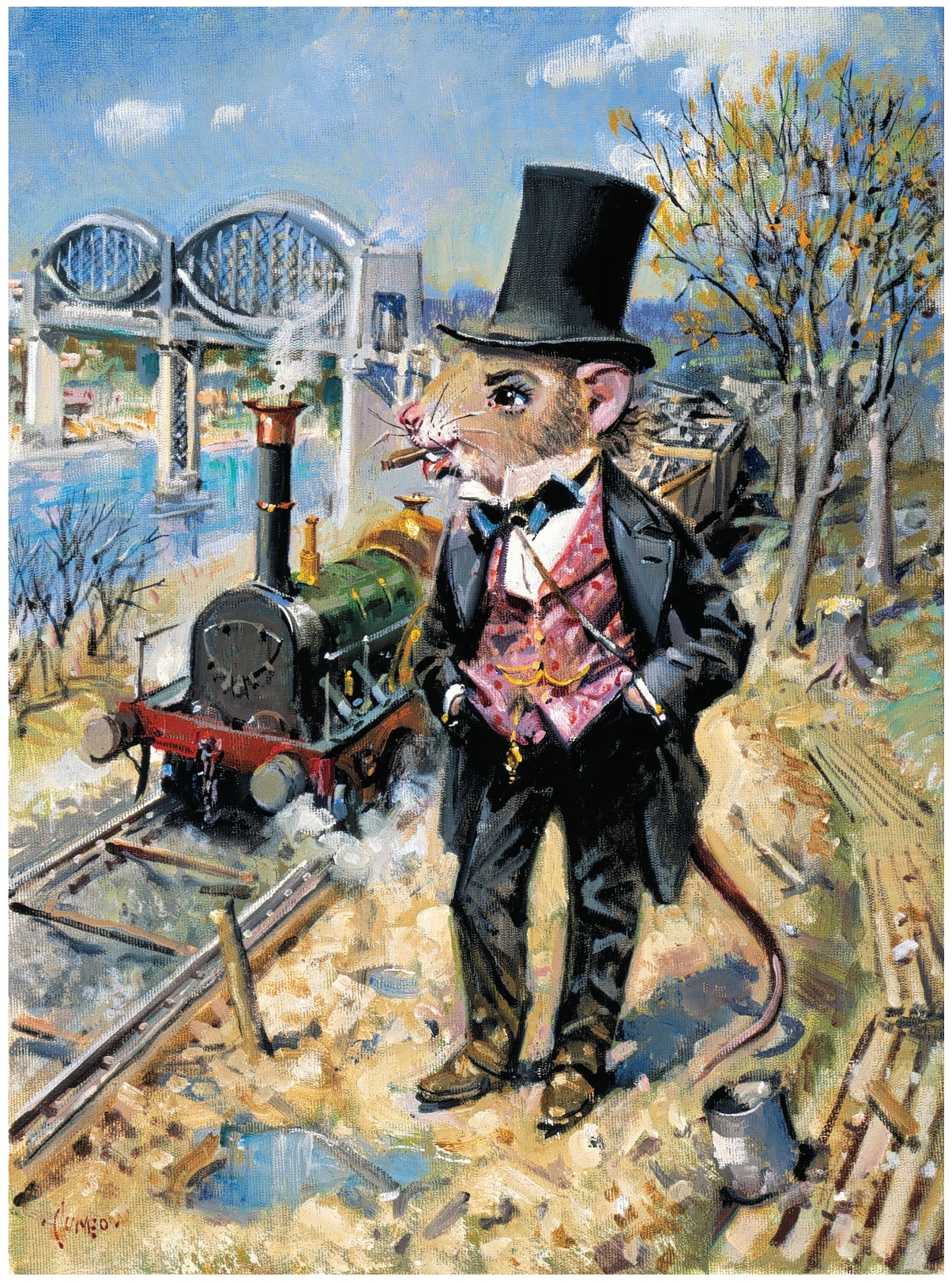

The late great railway artist Terence Cuneo had a mouse as his trademark, and in this magical cartoon of the completion of the Royal Albert Bridge, the rodent became crossed with Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Was it from the same family that gnawed the leather flap on the atmospheric South Devon Railway and forced its early closure, I wonder? COURTESY CAROL CUNEO

The Cornwall Railway was promoted in late 1844, just after Brunel had completed the Bristol & Exeter Railway. Captain William Moorsom, who had been involved with the Bristol & Gloucester Railway eight years previously, was asked by local businessmen in 1843 to survey a line and draw up plans for a 66-mile line from the South Devon Railway at Plymouth to the naval port of Falmouth.

He talked of a ‘floating bridge’ or train ferry to cross the Hamoaze, the name given to the estuary of the tidal Tamar opposite Devonport, and had at first considered to work the Cornish line by atmospheric propulsion.

After the first scheme was thrown out by the House of Lords, Isambard replaced Moorsom and was appointed engineer for the project, and carried out a new survey, this time calling for a high-level bridge across the Tamar.

This vastly improved plan was passed by Parliament on 3 August 1846, and as expected, Isambard opted again for broad gauge.

An alternative 1845 proposal for a Central Cornwall Railway, taking the time-honoured coach road through the middle of the county, and backed by the GWR’s great rival-to-be, the London & South Western Railway, failed to win approval.

However, while drawing up that scheme, the LSWR had bought out Cornwall’s first public railway, the Bodmin & Wadebridge, in the vain hope of using it as part of the route. The action left the LSWR with a ‘white elephant’ to which it would not connect for 40 years, but it dashed Cornwall Railway’s hopes of a broad-gauge branch to the port of Padstow.

All alone – before the coming of the modern suspension bridge, Brunel’s rail crossing of the Tamar as seen in the early 20th century. ROBIN JONES COLLECTION

An Illustrated London News view of the newly opened Royal Saltash Bridge. BRUNEL 200

Work on the Cornwall Railway began at Truro in 1847, but little work was done for several years because money kept running out. This was the time when the first great wave of Railway Mania was beginning to falter and backers for schemes were becoming scarce.

Meanwhile, further west in the Duchy, the standard-gauge Hayle Railway opened in 1837, running from Hayle Foundry to Pool and Portreath, and extending to Redruth the following year. Its primary aim was to connect the Redruth-Camborne mining areas to the coast, and steam locomotives were used from the start over most of its system.

On 3 August 1846, the West Cornwall Railway received authorisation and took over the Hayle Railway, intending eventually, to convert it to broad gauge, extend it to Penzance in one direction and Truro in the other, thereby meeting up with the future Cornwall Railway. Isambard was brought in as engineer on the West Cornwall too, and became chairman of its board from 1847-8.

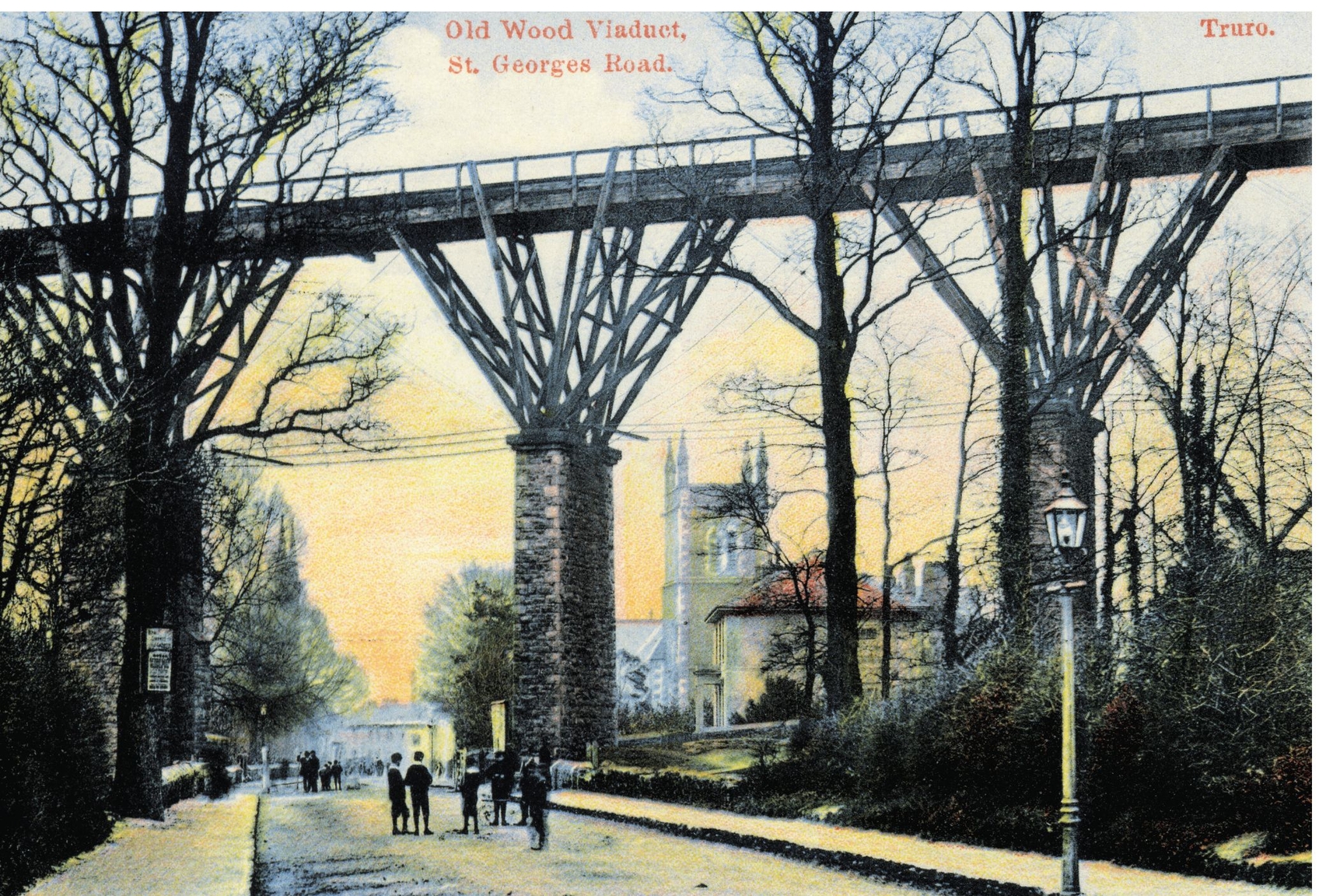

A colour postcard of Brunel’s viaduct in Truro, highlighting the typical fan-like construction of the supports. Although replaced in 1902, five of the piers survive in Victoria Gardens. These ‘cheap’ yet sturdy viaducts enabled the Plymouth to Penzance lines to be built. BROAD GAUGE SOCIETY

Under Isambard’s jurisdiction, the West Cornwall was completed between Penzance and a temporary Truro terminus in 1851, opening on 11 March 1852.

While mineral traffic on the line was of paramount importance, the West Cornwall opened up the prospect of easier travel to London for those living at the far end of the county for the first time. You could travel from Penzance or Truro to Hayle, take the paddle steamer packet service on to Bristol and travel onwards by the GWR.

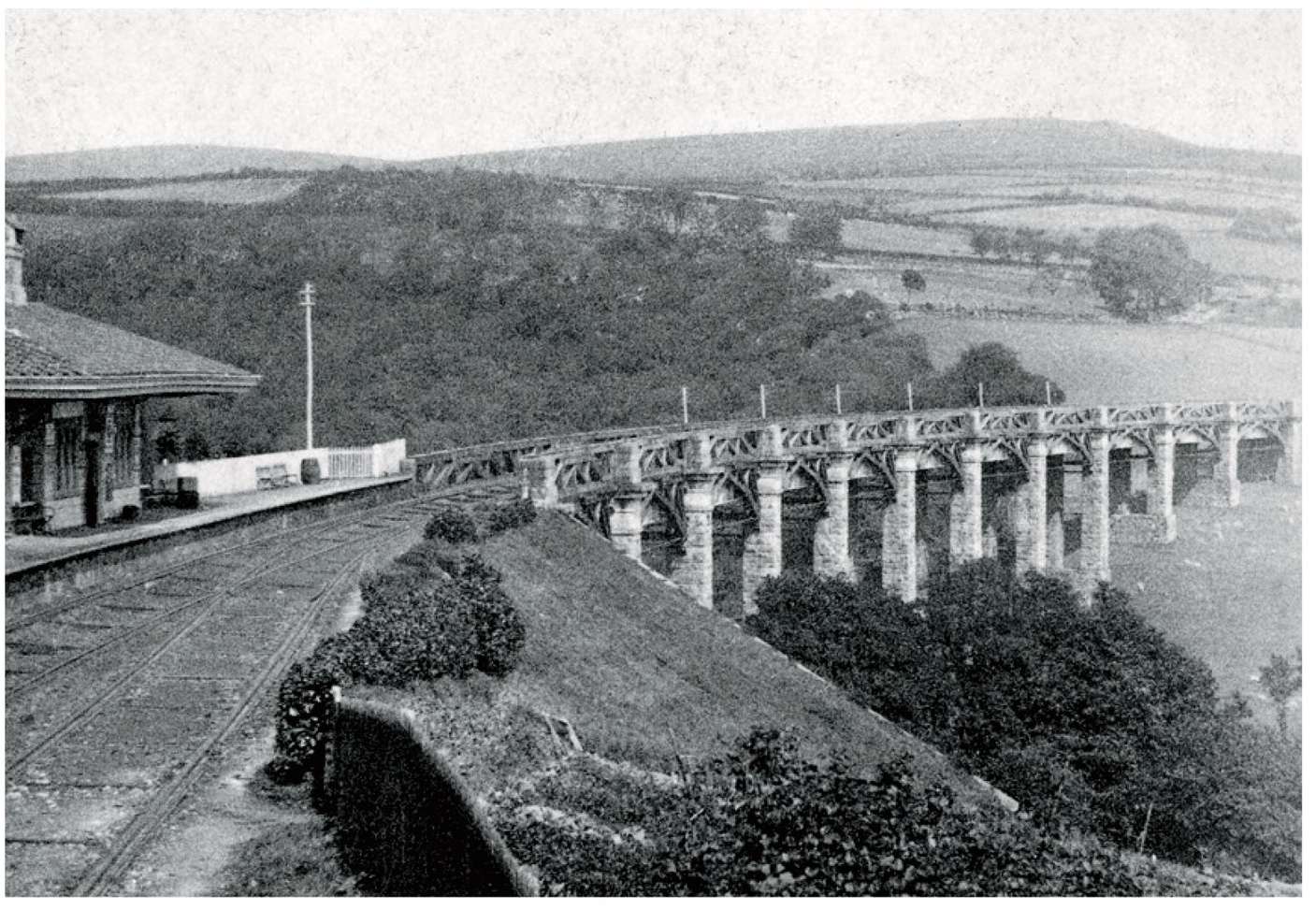

Isambard’s Cornwall Railway route involved no fewer than 34 viaducts over the 53 miles between Plymouth and Truro, each built in timber, just like several that had been on the later sections of the South Devon Railway, including the 670ft-long Ivybridge Viaduct, and also the 1760ft Landore Viaduct in South Wales.

The wooden viaduct on the South Devon Railway main line at Ivybridge was typical of the type which made the building of Brunel’s Cornwall Railway economically possible. BROAD GAUGE SOCIETY

Nine more were to follow on the West Cornwall, as a total of eight river estuaries and 30 valleys were crossed.

His distinctive trestle structures – known as fan viaducts because of the shape of the supports – involved timber constructions of masonry pillars, and were a cost-effective way of crossing the steep Cornish terrain.

These were far longer and more complex than his first timber bridge, a five-span affair, which carried a public road across Sonning cutting.

Although they were all were replaced from the late 19th century onwards with more expensive and longer-lasting stone alternatives, the old columns can still be seen standing alongside the new crossings at places like Moorswater.

Mindful of criticism that wood, mainly Baltic pine, could rot away, the viaducts were designed by Brunel in such a way that any offending timbers could be unbolted and replaced without having to close the line. Many of them lasted for 60 years, and it was only after the price of timber became too high after the outbreak of WWI that there was a mass movement to replace them with masonry.

The last to survive in Cornwall was College Wood Viaduct on the Falmouth branch, which stayed in situ until 1934.

In a bid to revive the stalled project, following years in the financial doldrums, Isambard announced in 1851 that he had found contractors to build the Cornwall Railway for £800,000, albeit single rather than double track, but the offer was not taken up. Hopes rose again when contracts for the key Plymouth-Saltash section were placed the following year.

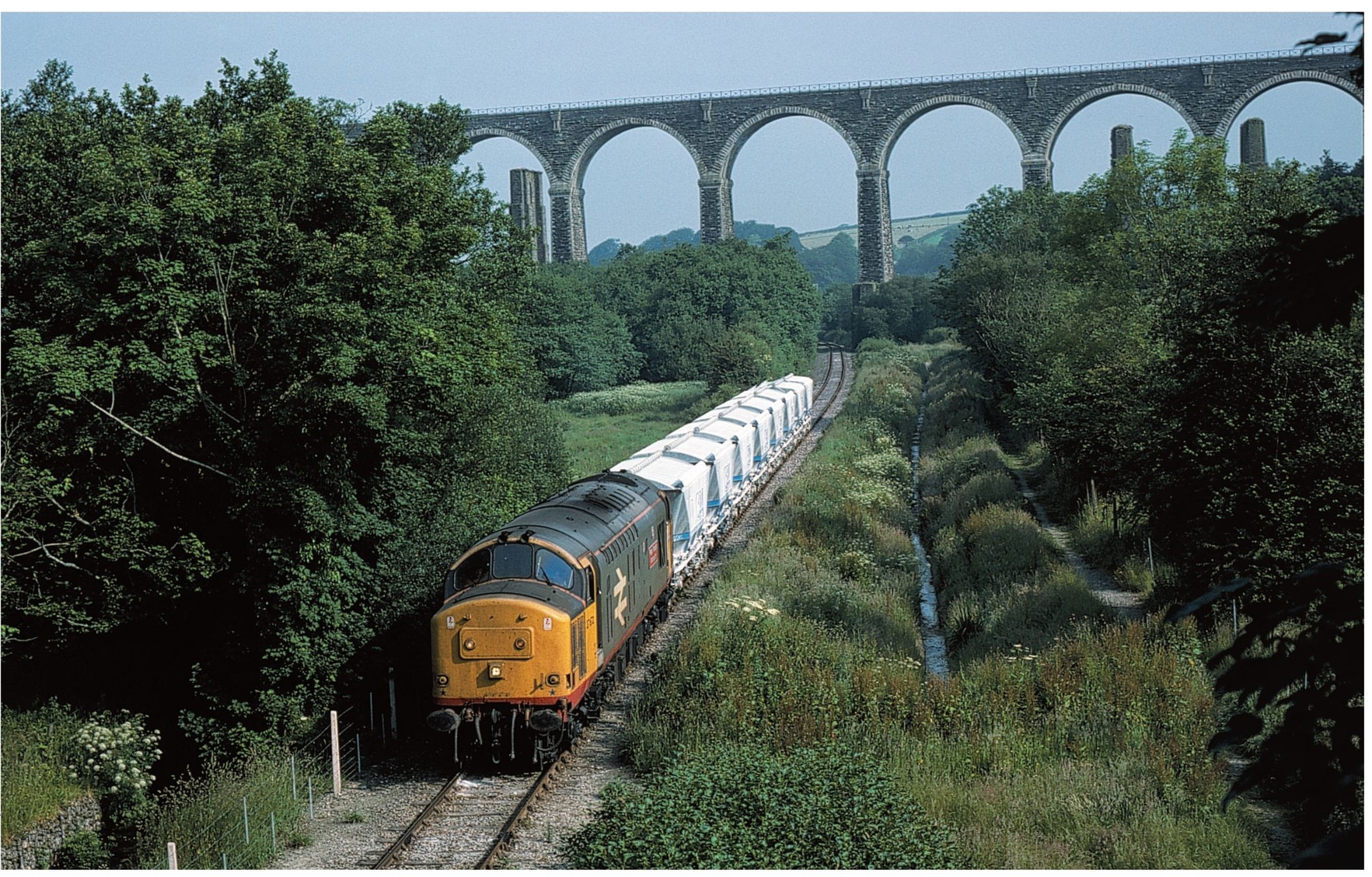

A Class 37 diesel on the Looe branch in the 1980s at Moorswater. Note the surviving stumps of Brunel’s Cornwall Railway wooden trestle viaduct rear in front of the later replacement. BRIAN SHARPE

The GWR, Bristol & Exeter and South Devon Railway took on a partial lease of the project from 1855, and continued to bail it out as construction proceeded in piecemeal fashion.

It was left to Isambard to tackle the biggest hurdle of them all – the Tamar, which at Saltash is 1100ft wide and 70ft deep.

At first he suggested building a timber bridge with one main span of 255ft and six further spans of 105ft each, but the Navy insisted that any crossing must allow headroom of 100ft to clear the masts of tall ships.

He then suggested a single-span bridge to clear the estuary in one fell swoop, but the estimated £500,000 cost was way beyond the reaches of the Cornwall Railway.

Isambard then came up with a truly stunning and radical design, which more than made up for his disastrous fling with atmospheric propulsion, a mode by now long deleted from the Cornwall Railway scheme.

His Tamar crossing featured two arched tubular girders, fastened to four cast-iron columns in the middle of the river, supporting by suspension a pair of 450ft spans, which would carry a single-track railway from one side of the river to another – a double-track version had been slimmed down, again to save money.

After test borings beneath the mud of the riverbed, a huge wrought-iron cylinder was sunk in the middle of the estuary, after a highly complex and elaborate operation.

Inside, workmen toiled away in hellish conditions at the bed of the river, digging down to the rock strata so that a solid granite column could be fixed in it. The column supports the cast-iron pillars supporting the great tubular arches.

Isambard drew much from his design for the Usk Bridge at Chepstow, and his use of tubular steel harked back to the far humbler swing bridge at Bristol’s Floating Harbour.

The tubular girders were assembled on the east bank and weighed 1060 tons when finished. They were floated across the river into position on pontoons, after a special dock was cut in the Devon bank, and jacked up with hydraulic presses to the required height; this truly spectacular operation began on 1 September 1857.

Attached to each tube were the suspension chains, linked to each other by 11 uprights. Diagonal bracing was added to provide extra rigidity.

Isambard had gained vast experience in lifting suspension bridges when he assisted Robert Stephenson in the construction of the Conway and Britannia bridges in North Wales.

The great bridge, which has an overall length of 730 yards, took seven years to build and cost £225,000. Despite the colossal expense by the day’s standards, the directors of the Cornwall Railway heaped praise on him, knowing that it would outlive their lifetimes and many more, acknowledging that it was nonetheless a truly economic solution.

After his death, the inscription, I K BRUNEL ENGINEER 1859, was ordered to be displayed above the entry arches in perpetuity. Everyone who travelled to Cornwall and passed through the unique structure would immediately be told the name of its designer.

By the time the bridge was finished, the remainder of the Plymouth-Truro line had been completed, all ready for the first trains.

The structure was named the Royal Albert Bridge, as it was the Prince Consort who opened it officially on 2 May 1859.

Both banks of the river were packed with onlookers, while others crowded on hills and rooftops overlooking the river, desperate for a glimpse of the proceedings. A flotilla of steamers and small boats plied their way up the Hamoaze for a grandstand view. The last county in Britain without a link to the national rail network was now connected.

VIPs from Cornwall, including the mayors of Truro and Penzance, arrived by train and were presented to the prince. The following day, a grand civic banquet was held in the Town Hall at Truro to serve guests who had arrived on a special train, which left Plymouth at 10.30am and arrived shortly before 1pm.

A view of St Ives station with a fine array of broad-gauge wagons on show. BROAD GAUGE SOCIETY

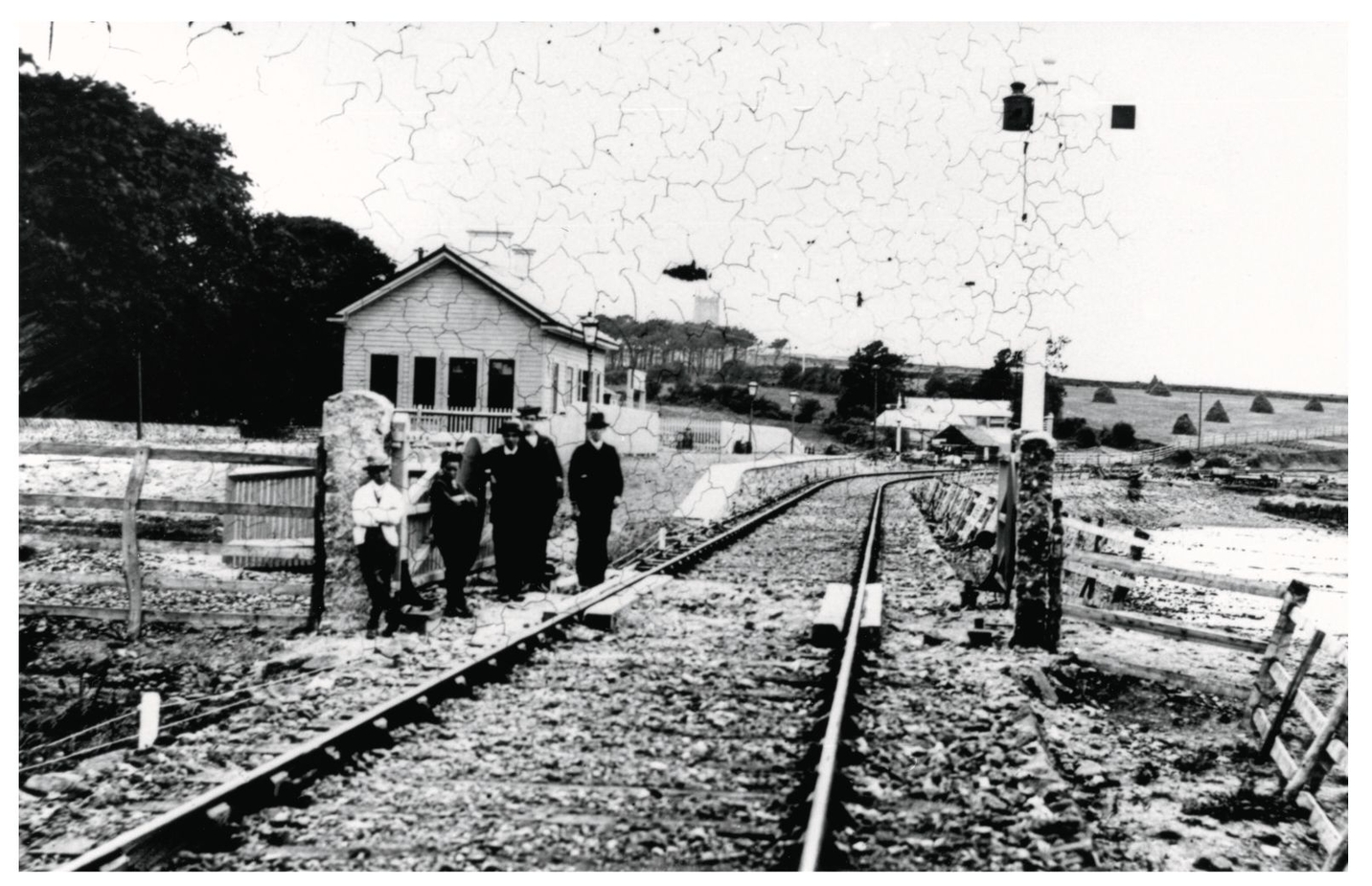

Lelant on the St Ives branch, the last passenger-carrying line to be built to Brunel’s broad gauge. BROAD GAUGE SOCIETY

This third section of a Cornwall Railway broad-gauge coach from the mid-19th century ended up being used as a track ganger’s hut in Grampound Road, from where it was retrieved by National Railway Museum staff in 1977 and restored for display at its headquarters in York. ROBIN JONES

It was said that everyone living in the towns and villages along the route had turned out to cheer and wave the train on as it passed.

On 4 May, the Cornwall Railway was opened to the public. At last the county, which had produced Richard Trevithick, inventor of the first railway locomotive, was connected to the national network, and thereby to London. The world had suddenly grown much smaller, and the Tamar was, for the first time in history, no more a barrier.

One important person was sadly absent from the opening celebrations. Isambard Brunel.

In deteriorating health, he was too ill to attend, but did manage to ride across the bridge a few days later, lying couch mounted, on a truck pulled by a Gooch engine.

The final part of the original Cornwall Railway route, from Truro to Falmouth, had to wait another four years before it was opened. Work had begun in 1850, but stopped when the contractor failed. Renewed calls for its completion were made loudly in 1861 when new docks at Falmouth were completed, and it finally opened on 24 August 1863.

By then, however, Falmouth had declined in importance in transport terms, with the Royal Mail Packet Service fleet having been transferred from here to Southampton, after more than 150 years. The result was that the line to Truro would remain a branch line, not the intended main line, which now ran on to Penzance.

In 1864, the Cornwall Railway exercised its right to demand that the West Cornwall, which was still standard gauge, laid a broad-gauge rail to accommodate through trains. It could not afford it, and so it was leased to the consortium of the GWR, Bristol & Exeter and South Devon Railway, which immediately laid the third rail.

At last, on 1 March 1867, a through service between Paddington and Penzance was begun, with locomotives supplied by the South Devon Railway. At last, the great dream of those who had launched the GWR more than a third of a century before had been realised, and the future tourist trade of the West Country was assured.

Furthermore two subsequent offshoots of the West Cornwall deserve special mention.

A branch nearly five miles long from St Erth on the mainline, to St Ives was authorised in 1876 and opened on 1 June 1877. It was the last new Brunel broad-gauge line to be built, and became the property of the GWR the following year.

The short standard-gauge Hayle Wharf branch had a third rail added when it was extended along the quaysides, and opened for goods traffic only on 3 October 1877.

Cornwall is famous for its sunsets, and here was the twilight of Isambard’s 7ft 0¼in gauge empire, which had stretched from London, north to Wolverhampton and westwards to Milford Haven and now Penzance.

The Royal Albert Bridge has been strengthened several times since it was built, and the station at Saltash at the western end still retains its original 1859 building.

In the Macmillan years when we ‘never had it so good,’ the car became king as more and more people could afford to buy one, and as a result many West Country branch lines began to close, even before Dr Richard Beeching wielded his axe in 1963.

The following year, a second Tamar crossing was opened alongside Brunel’s, a modern suspension bridge taking the A38 from Plymouth to Saltash, replacing the car ferry that ran below.