Chapter 18

THE GREAT EASTERN

The Final Epitaph

I sambard Brunel wasn’t a man to be discouraged. Barely had the Great Western Steamship Company been wound up in 1852, after selling off the SS Great Britain in the wake of its Dundrum Bay disaster, but he was back at work drawing up plans for a far bigger steamship.

William Hawes, chairman of the Australian Royal Mail Company, appointed Isambard as consultant engineer to the newly formed shipping line, giving him a brief to build a vessel which would need to refuel only once en route, at Cape Town.

In turn, Isambard called on the services of an old friend, highly acclaimed naval architect, John Scott Russell, a key figure in the building of the Crystal Palace and secretary of the Royal Society of Arts, to produce the design for the steamship to his specifications.

Isambard came up with the idea for a ship with a displacement of between 5000 and 6000 tons, which the company said was too big. Instead, they opted for two smaller ships, also built to Brunel specification and Scott-Russell design, the Adelaide and the Victoria. The pair, built at Scott-Russell’s Millwall shipyard, were ordered at the time of the Australian gold rush, when it seemed that a regular service would more than pay its way.

Privately, Isambard began working on a plan for a far bigger ship, which would be capable of running a regular service to either India or Australia.

His plan involved a ship 600ft long; nearly double the length of the SS Great Britain.

Russell and Isambard’s old steamship colleague Christopher Claxton helped him develop the design, which would have a displacement of up to 21,000 tons, an engine of at least 850 horsepower, a bunker to store up to 10,000 tons of coal and capable of averaging 15 knots.

Isambard also came up with the notion of using a combination of a propeller and paddle wheels.

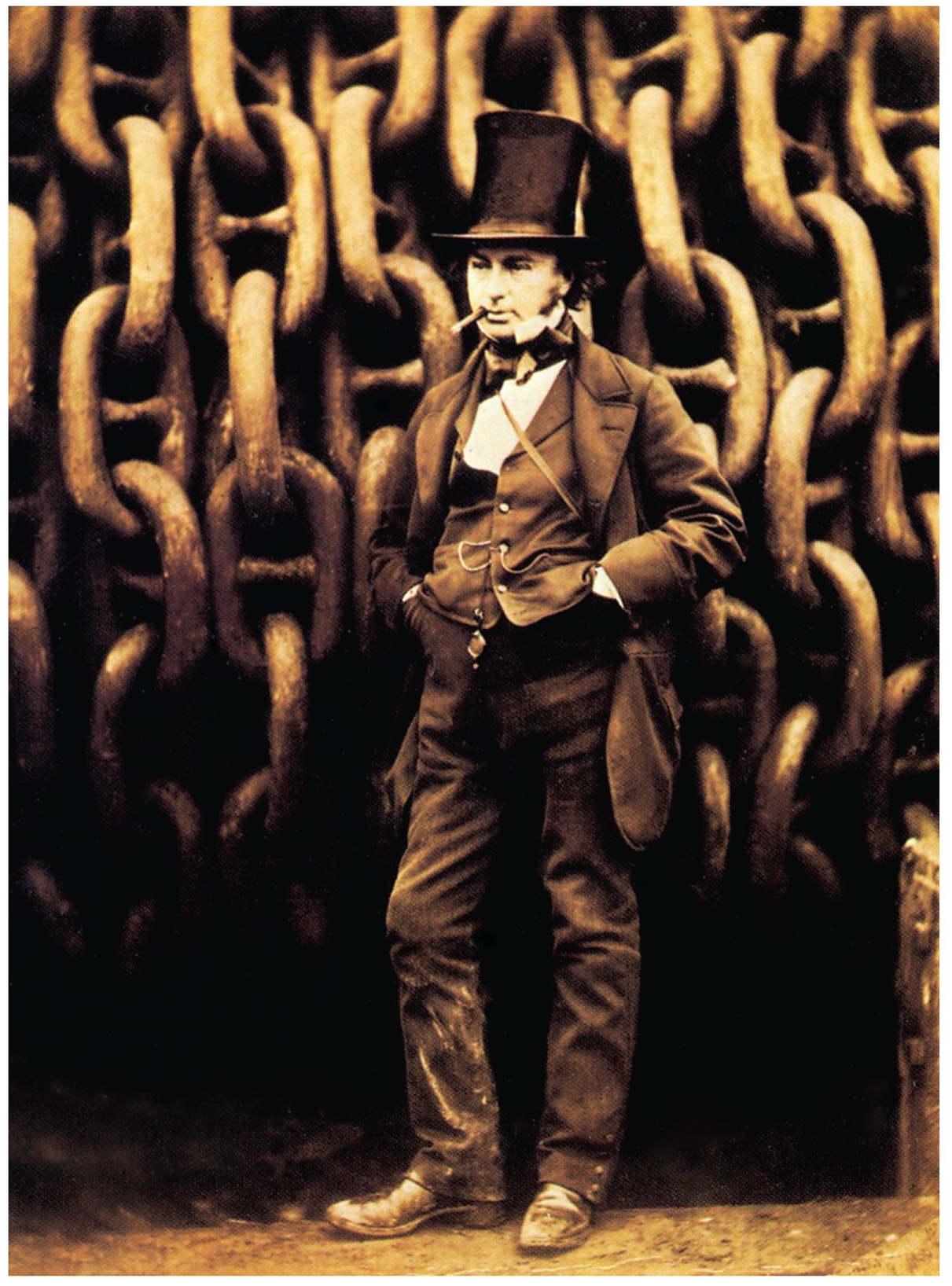

This photograph of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, complete with cigar, was taken at Napier’s yard, in the Isle of Dogs, in November 1857. He is standing alongside the great chains used for launching the Great Eastern. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

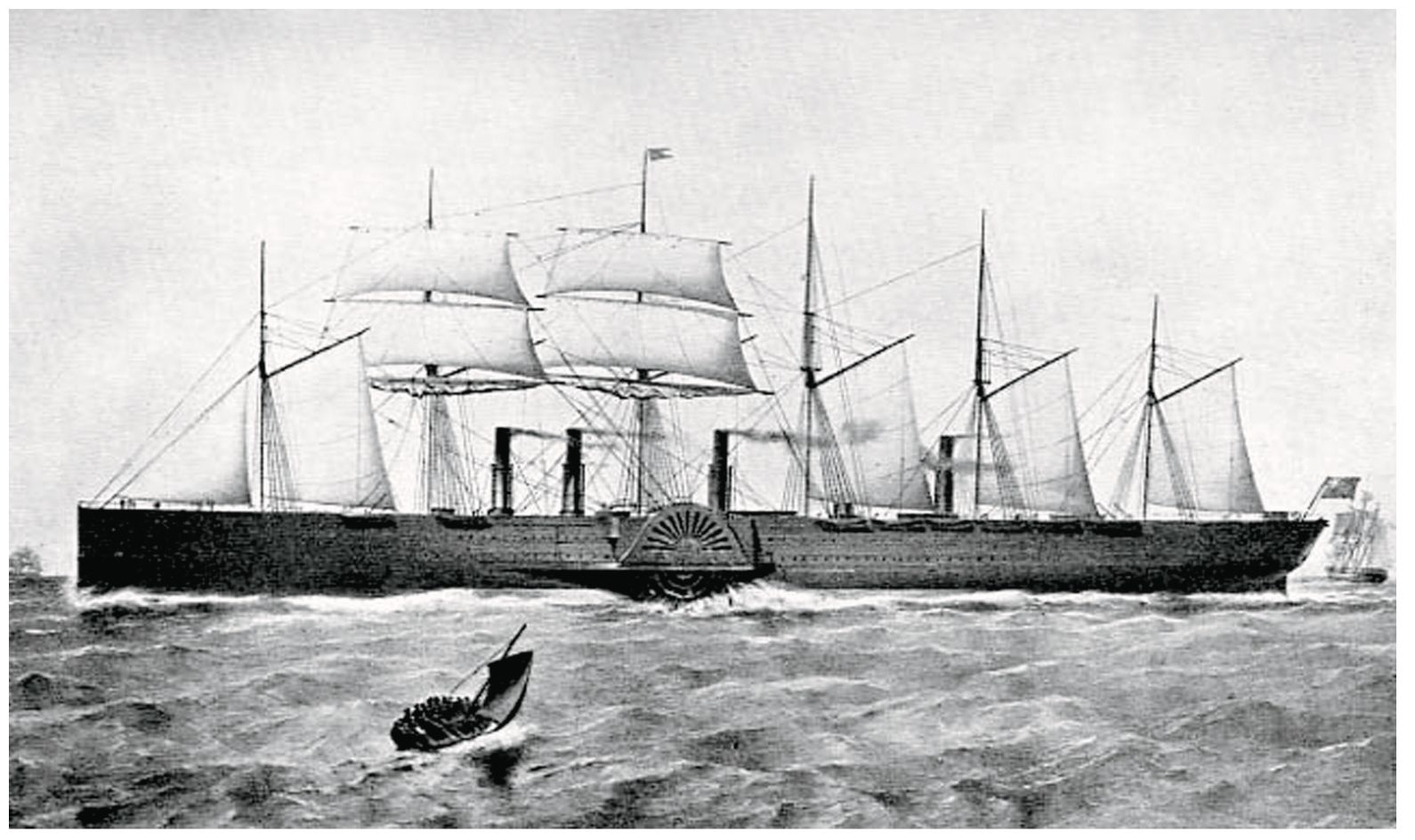

Brunel’s mighty ship was launched in 1859, and grossing 18,915 tons, it held the record for the largest ship ever constructed for 43 years. WESSEX WATER HISTORICAL ARCHIVE

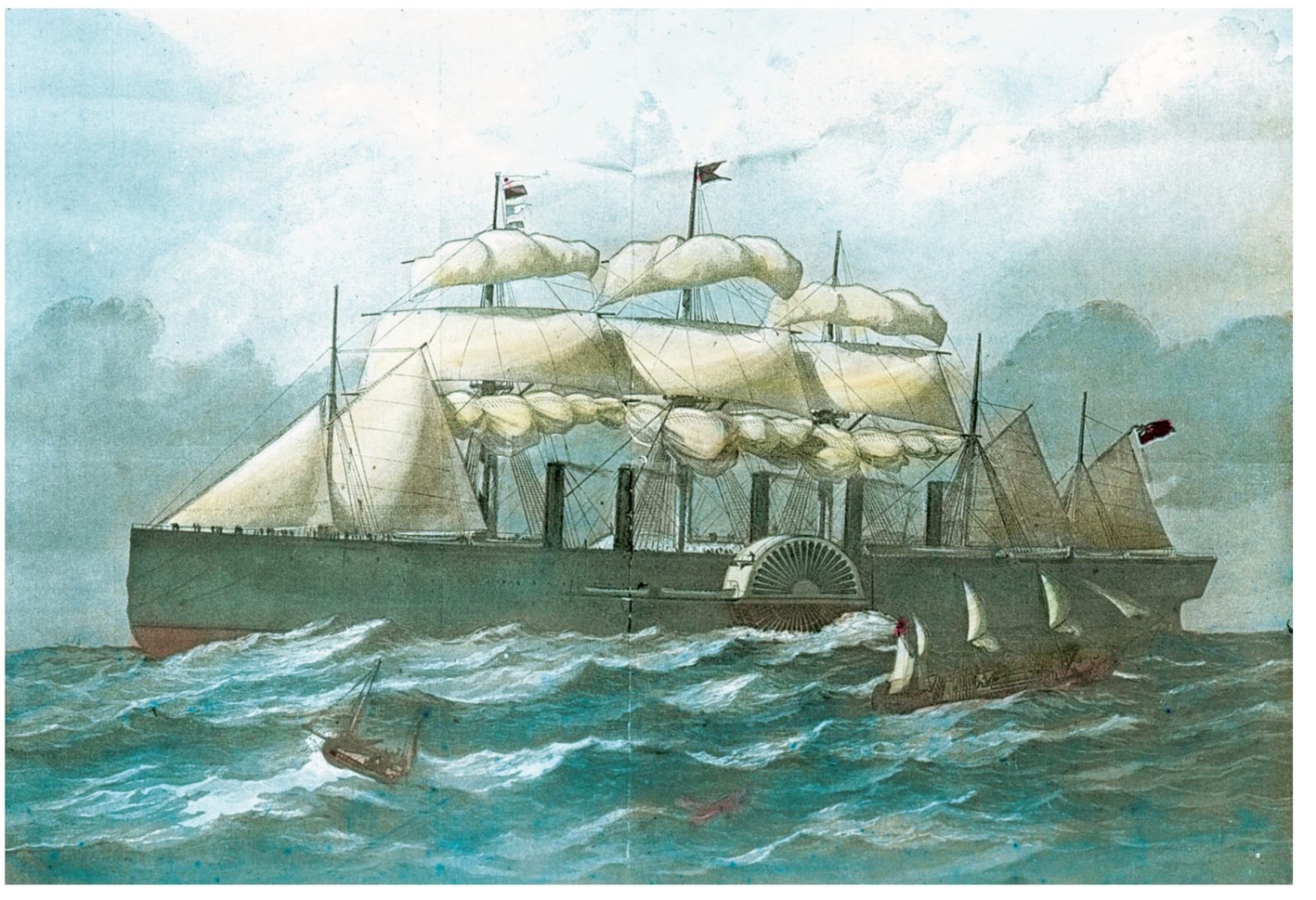

SS Great Eastern on its maiden voyage as painted by Samual Walters. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

Such a design would be pushing the technology of the day to its limits, but any distant warnings from the ghost of the atmospheric railway went unheeded.

The Eastern Steam Navigation Company, which had been looking at running services to India, China and Australia, was receptive to Isambard’s design, which was presented to them by Scott Russell. The proposal split the company’s board, with some directors quitting over it, while others were lured by the prospect of massive profits to be made from a gargantuan cargo carrier.

The company went for it, and Isambard was appointed engineer. As he tried to interest investors in subscribing to the project, the company was insisting that work could only start when £800,000, or 40,000 shares had been invested.

Contracts for the ship were finally signed on 22 December 1853, with Scott Russell successfully tendering to build the ship for £377,200.

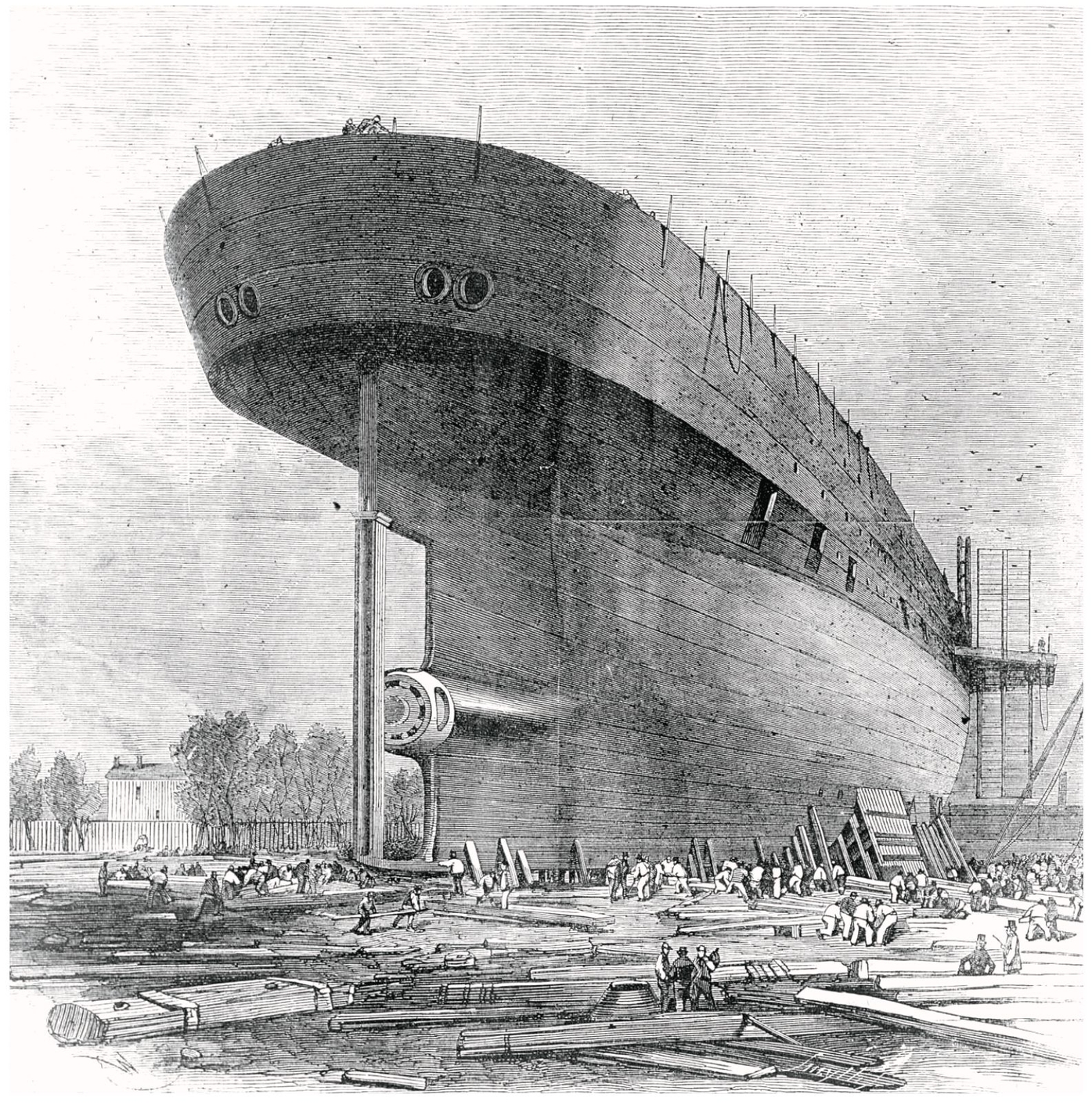

The Great Eastern under construction showing stern and propeller shaft. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

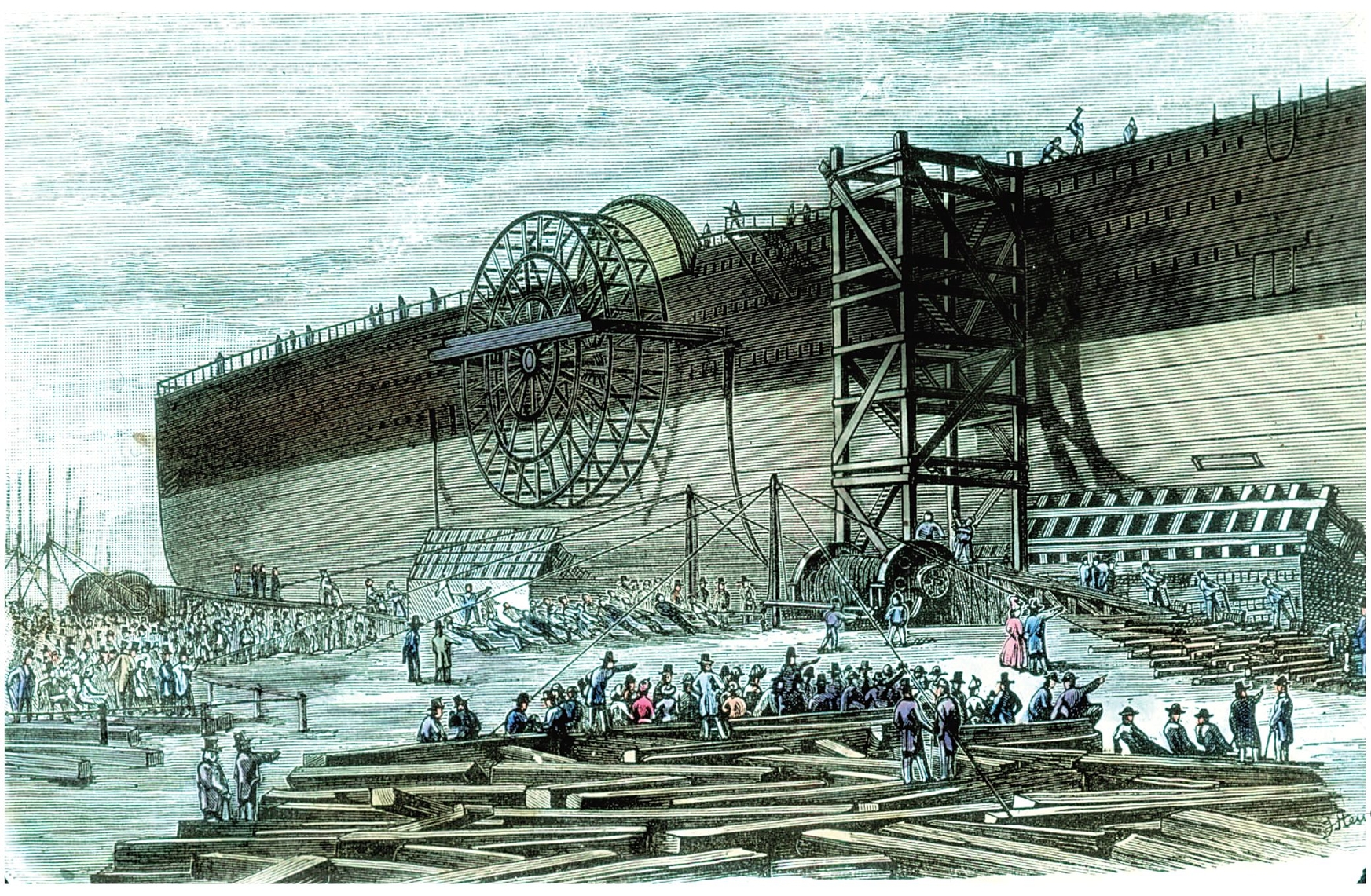

The Great Eastern being launched. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

Russell’s shipyard was deemed too small for the monster ship to be built inside it, and, as the company could not afford to build a berth for the project, space was leased in David Napier & Company’s yard next door.

Building work began in the spring of 1854. The ship utilised a new design of hull, one that featured girders running between an inner and outer skin. It was to be 680ft long, with an 83ft beam.

In February 1856, Scott Russell went broke, and creditors took over his business, with only half the hull built.

The Eastern Steam Navigation Company then took over both the ship and the Napier yard and resumed work. Scott Russell stayed on as one of Isambard’s assistants and greatly furthered progress on the project. However, Isambard was displeased that Scott Russell had made decisions on his own, while he’d been in charge, during the former’s absence through illness.

A major disagreement between them led to Scott Russell taking a holiday, never to return to the Eastern Steam Navigation Company, and leaving Isambard in sole charge of the 1200-strong workforce.

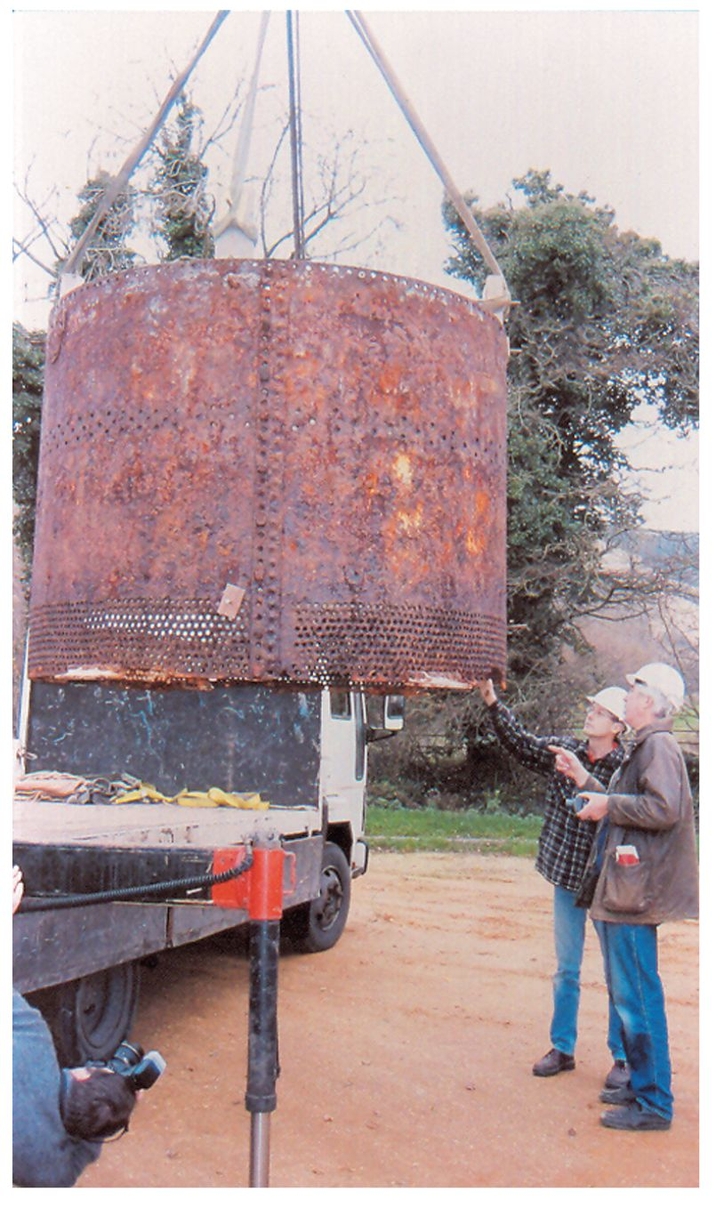

The funnel/ strainer, the only remnant of Brunel’s Great Eastern, was removed from the Sutton Poyntz pumping station reservoir in 2003 and is seen on its way to the SS Great Britain Museum in Bristol. The holes drilled in the funnel in 1860 to convert it into a strainer, can be clearly seen. WESSEX WATER HISTORICAL ARCHIVE

There had been much debate between Isambard and Scott Russell on how the ship should be launched. Scott Russell had wanted to slide it down greased-timber launching ways, in its wooden cradle – the time-honoured way. Isambard was concerned that there would be insufficient control, and in autumn 1856 had iron plates fixed to the underside of the cradles, with iron rails laid on the launching ways.

By November 1857, the hull was ready and Isambard wanted to test the launching system. Huge chains were fastened to the launching cradles and linked to massive steam winches on Thames barges. The idea was that once the ship began to slide, its movement would be restrained by the weight of the huge chains wound on to drums.

The hull would be lowered to the low-water mark, and would float when the tide came in.

As expected, a massive crowd turned out to witness the launch, for which the cash-strapped company had sold tickets. The event began with the official naming, with Miss Hope, daughter of the company chairman, breaking a bottle over the bow.

She named the vessel, but disaster struck when the crew operating the winch drum restraining the hull’s stern, diverted their attention momentarily, and its handle spun out of control. A labourer was thrown into the air as the hull lurched forward 4ft. He died of his injuries a few days later, and four others were also injured.

A second attempt to launch the behemoth failed the same day, and what was worse; the whole debacle had taken place in full view of the crowd.

Isambard brought more hydraulic presses and rams to the yard and eventually, on 31 January 1858, the ship was floated and then moored off Deptford.

By this time, costs had escalated to £600,000, well above Scott Russell’s low tender – and a further £100,000 was needed to install the engines. The launch had also cost £120,000.

Everyone had lost money in the venture, and Isambard had been so determined to finish building the ship that he allowed his health to suffer.

In May 1858, Isambard and his wife Mary took a holiday in Switzerland in a bid to recuperate, but he was not well enough to return for Queen Victoria’s visit to the ship the following month.

By the time he came home in the autumn, the Eastern Steam Navigation Company was looking for a way out.

A new firm, the Great Ship Company, was formed, and in buying the hull for £165,000, it allowed the ESN to be wound up.

Despite his failing health – a kidney ailment – Isambard eagerly accepted the position of engineer to the new firm.

Coincidentally, while he spent that winter convalescing in the Mediterranean, travelling on to Egypt and Cairo, he met up with none other than Robert Stephenson. Meanwhile, the new company began fitting out the hull – and accepted a tender to do so from Scott Russell, who by this time had recovered his business.

The paddle engines were tried out in July 1859, and Isambard, his health deteriorating rapidly – his illness having been only too apparent at the opening of the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash at the beginning of May – attended whenever he could.

He was unable to turn up for a celebratory banquet on board, organised by Scott Russell on 5 August, but he remained determined that nothing would stop him from going on the maiden voyage.

Isambard visited the ship on 2 September, but after two hours, he collapsed and had to be taken home. He had suffered a heart attack.

The maiden voyage was finally set for 7 September, and the Great Eastern, as it was by then known, moved from her moorings and headed off down the Thames bound for Weymouth and Holyhead.

Isambard was confined to bed in his Duke Street house, but nonetheless insisted on receiving news of his ship, which brought out the crowds as it passed every south-coast town.

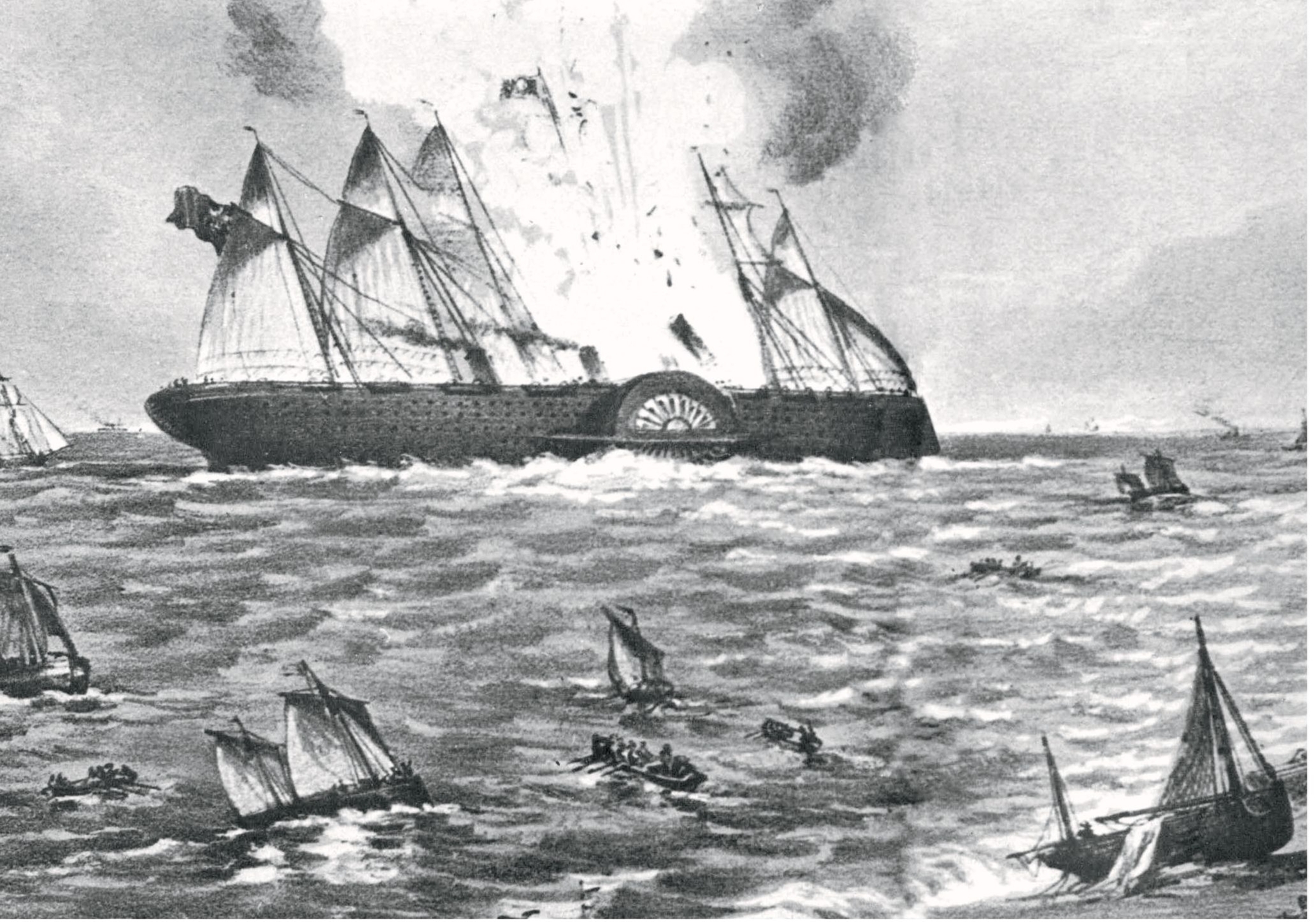

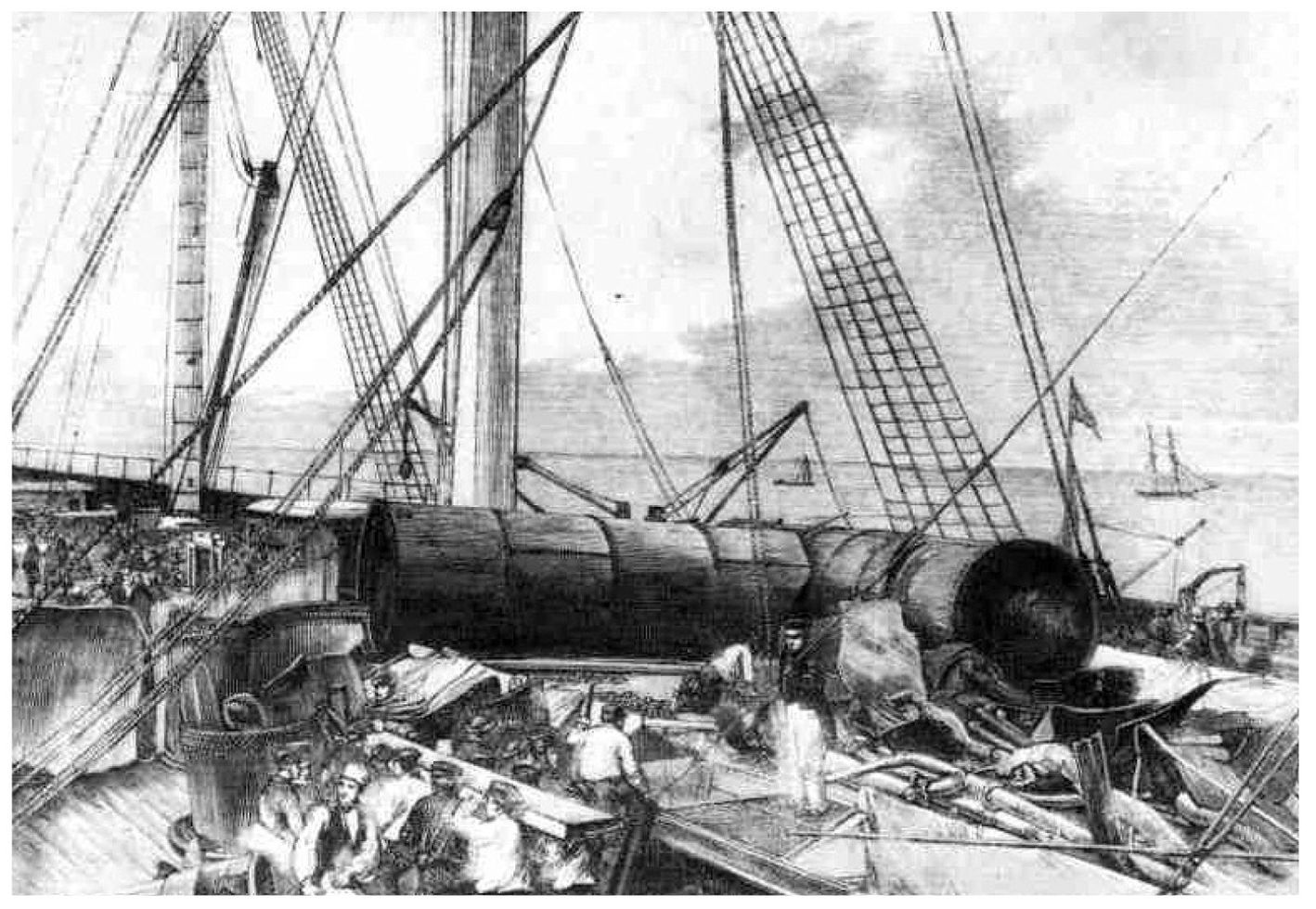

A contemporary illustration of the explosion which rocked the Great Eastern at Dungeness, and the fallen funnel afterwards. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

He even wrote to the Great Western Railway directors asking them to give all the workers at Swindon the day off, along with special passes so they could ride to Weymouth, in Dorset, by train and see his ship when it arrived.

It was the last letter he ever wrote.

Around 6pm on the evening of 8 September, when the ship was off Dungeness, an almighty explosion caused the ship’s forward funnel to fly 30ft into the air, along with a huge cloud of smoke and steam.

Five stokers were killed and others seriously injured. A stopcock on a water preheater on the funnel had been left shut, allowing pressure to build up and cause the explosion.

The Great Eastern was not badly damaged, and continued her journey the following morning, arriving in Weymouth, as scheduled, on 10 September.

Dismayed, Isambard heard about the tragedy that same day.

On 15 September, he called his family together for the last time, and died a few hours later, aged only 53.

His funeral, attended by a large contingent of GWR workers, along with his many friends and admirers, took place at London’s Kensal Green cemetery, five days later.

The greatest of engineers was laid to rest in the same tomb as his mother and father.

He never saw the fruits of the last of his labours, which many believed had killed him.

The Great Eastern was technologically everything Isambard had hoped she would be, and although she never ran on the routes to the Far East as the company that began the project had planned, she did steer a more valuable course, setting guidelines and standards for the future of shipbuilding.

It was not, however, a financial success. The Great Eastern sustained extensive damage in a storm off the south of Ireland on September 1861, while it had 400 passengers on board. The great storm damaged both the screw and the rudder, while the raging seas destroyed the paddle floats, leaving the Great Eastern helpless for three days.

Temporary repairs made by the crew helped her to return to Queenstown, in Ireland, where it was obvious that Isambard’s design had kept her afloat in a storm that would have sunk any other vessel.

The Great Ship Company went into liquidation five years after the launch, and on 14 January 1864, the Great Eastern was offered for auction, but failed to sell.

In April that year she was chartered to the Telegraph Construction Company to lay the first transatlantic telegraph cable between Europe and North America, a job which was completed on 1 September 1866.

The entreprener who led the venture – and was knighted for dooing so – was none other than Isambard’s locomotive superintendent Daniel Gooch!

Isambard would have been proud.

In 1867, his ship briefly went back to carrying passengers and when it departed from Liverpool for New York on 26 March, it was carrying the science-fiction writer Jules Verne and his brother Paul.

The Great Eastern, however, was far more commercially successfully as a cable layer, and in 1869, was chartered to lay the French transatlantic cable. In February 1870, she laid a cable between Bombay and Aden, in Yemen, in a fortnight.

In 1886, the Great Eastern was sold at auction for use as a floating fair and an advertising hoarding.

The following year, she was bought at an auction in Greenock, near Inverness, by ship breakers who moved her to Liverpool for dismantling, a process that began in May 1889 and lasted 18 months.

The only remaining piece of the ship’s structure is a section of funnel, which was adapted for use as a strainer at the Sutton Poyntz pumping station reservoir, near Weymouth, after the stricken Great Eastern had docked at the port for repairs in 1859.

In 2003, it was removed from the reservoir and donated by Wessex Water to the SS Great Britain Museum in Bristol, where it remains today.

The funnel of the Great Eastern lies on its deck following the explosion. SS GREAT BRITAIN TRUST

The stricken Great Eastern in Weymouth Bay in 1859. This rare stereo-card photograph shows the Great Eastern, after the explosion on 9 September 1859, moored and awaiting repairs – minus the forward (No 1) funnel. WESSEX WATER HISTORICAL ARCHIVE