Chapter 19

VICTORY OF THE NARROW MINDED

1892

Its inventor and champion gone, it seemed that there would be little standing between Isambard’s broad gauge and oblivion. However, it lingered on for a third of a century after his death, and nearly half a century after the Gauge Commission came down in favour of standard gauge, despite the facts in its favour.

It was the breaks of gauge that caused most concern, with more than 30 recorded in South Wales alone. As the smaller standard-gauge railway companies began to merge into large ones, more mixed-gauge lines were laid over part of the Great Western system. Mixed-gauge operation finally reached the heart of the broad-gauge system, Paddington, in August 1861.

When he became chairman, Daniel Gooch, who had been the most passionate supporter of Brunel’s broad gauge three decades before, no longer swam against an unstoppable tide, and instead moved towards large-scale conversion of GWR routes to standard gauge.

The first such gauge conversions took place in 1866, when broad gauge extended to 1427 miles, including 387 miles of mixed gauge. First to go were the lines north of Oxford by 1869 followed by the conversion of the South Wales main line in 1872. By 1873 around 200 route-miles in Berkshire, Wiltshire, Hampshire and Somerset had been changed over. The ‘dinosaur’, however, still insisted on giving birth, even on the brink of extinction, the aforementioned St Ives branch opening as broad gauge in 1877.

As more broad-gauge lines were converted, there became less investment in 7ft 0¼in gauge locomotives and stock.

The Bristol & Exeter opened its Cheddar Valley line from Yatton to Wells in 1869; when it was converted to standard gauge in November 1875, it became not only one of the shortest-lived broad-gauge lines of all, but the only part of the BER to be converted prior to absorption by the GWR two months later.

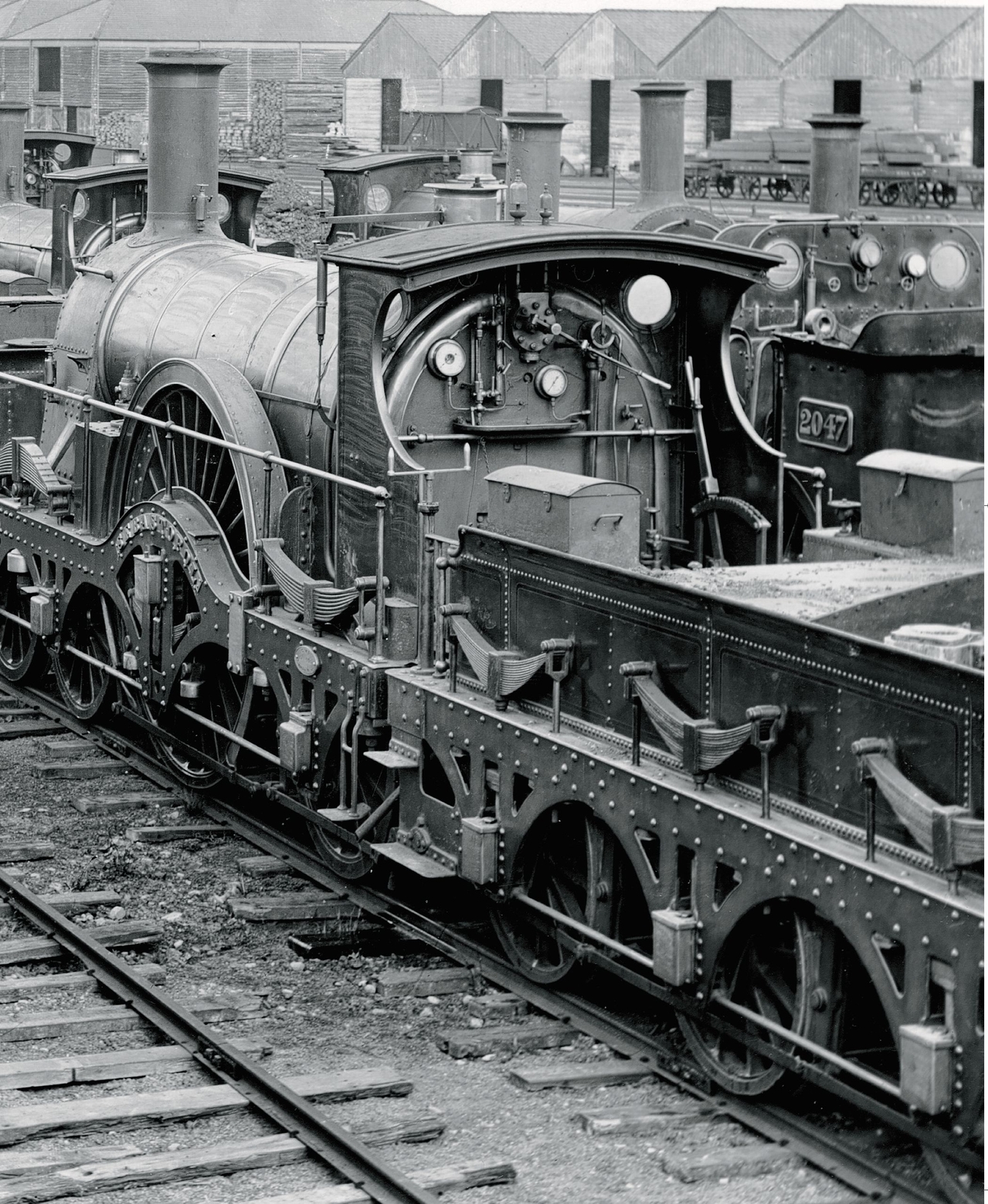

With nowhere left to run, rows of broad gauge locomotives await the cutter’s torch at Swindon in 1892, following the end of Brunel’s 7ft 01/4in gauge. The nearest on the right is Rover class 4-2-2 Sebastopol, which was rebuilt/renewed from an Iron Duke locomotive only four years before. GW TRUST COLLECTION

The last broad-gauge engine was outshopped from Swindon, Rover class 4-2-2 No 24 Tornado, in July 1888. By way of contrast, it had built its first standard-gauge engines in 1855, a year after absorbing its first 4ft 8½in lines, the Shrewsbury & Chester, and Shrewsbury & Birmingham railways.

Gooch died in 1889, and afterwards the final conversion was planned – that of the Paddington-Penzance main line in its 177-mile entirety.

The operation was planned to the exact detail, with the general manager at Paddington issuing 80 pages of instructions on how it should be done.

Track work was prepared for removal and new rails and sleepers brought in ready, while standard-gauge locomotives and coaches were moved to strategic points along the great route on broad-gauge wagons.

D-Day was named as Saturday 21 May 1892, when more than 4200 tracklayers gathered along the line, after the last broad-gauge engines had steamed back to Swindon to be herded into 15 miles of temporary sidings on a three-acre site, bought especially to store them pending scrapping. A total of 196 engines, 347 coaches and 3544 wagons survived to the end.

The last broad-gauge train from Paddington was the 5pm to Plymouth on the Friday, hauled by Rover class locomotives Bulkeley to Bristol and Iron Duke from there to Newton Abbot. Bulkeley also worked the final train to London, the night mail, which reached Paddington at 5.30pm on the Saturday.

The last broad-gauge train from Penzance was a 9.10pm empty stock working, hauled by two ‘convertible’ locomotives, which would thereby escape immediate scrapping. As the last 7ft 0¼in gauge train passed through each station, the stationmaster had to confirm to the inspector aboard that there was no broad-gauge stock in his sidings.

The inspector then presented the stationmaster with a certificate, which was handed over to the line engineer as the signal to begin the conversion.

The line free of trains at last, the platelayers and gangers got down to business, the final conversion being scheduled for completion for just after 4am on the Monday.

It all went ahead as planned. Brunel would have winced at the loss of his broad gauge, but would also surely have marvelled at the mammoth operation carried out in such a short space of time with the minimum of inconvenience to traffic.

The mail train from Penzance to Paddington, which departed Plymouth at 4.40am on the Monday, was the first to run the length of the new all standard-gauge premier route. After the curtain fell on a proud era of our railway history, it heralded a new dawn, presenting the successors to Brunel and Gooch with many exciting new challenges and successes on the Great Western Railway they had built.

The last GWR broad-gauge engines to run were South Devon Railway 4-4-0 saddle tanks Leopard and Stag. Both were used at Swindon for shunting broadgauge stock into the cutting shop for scrapping until June 1893, when they befell the same fate. There was nowhere left for them to run.

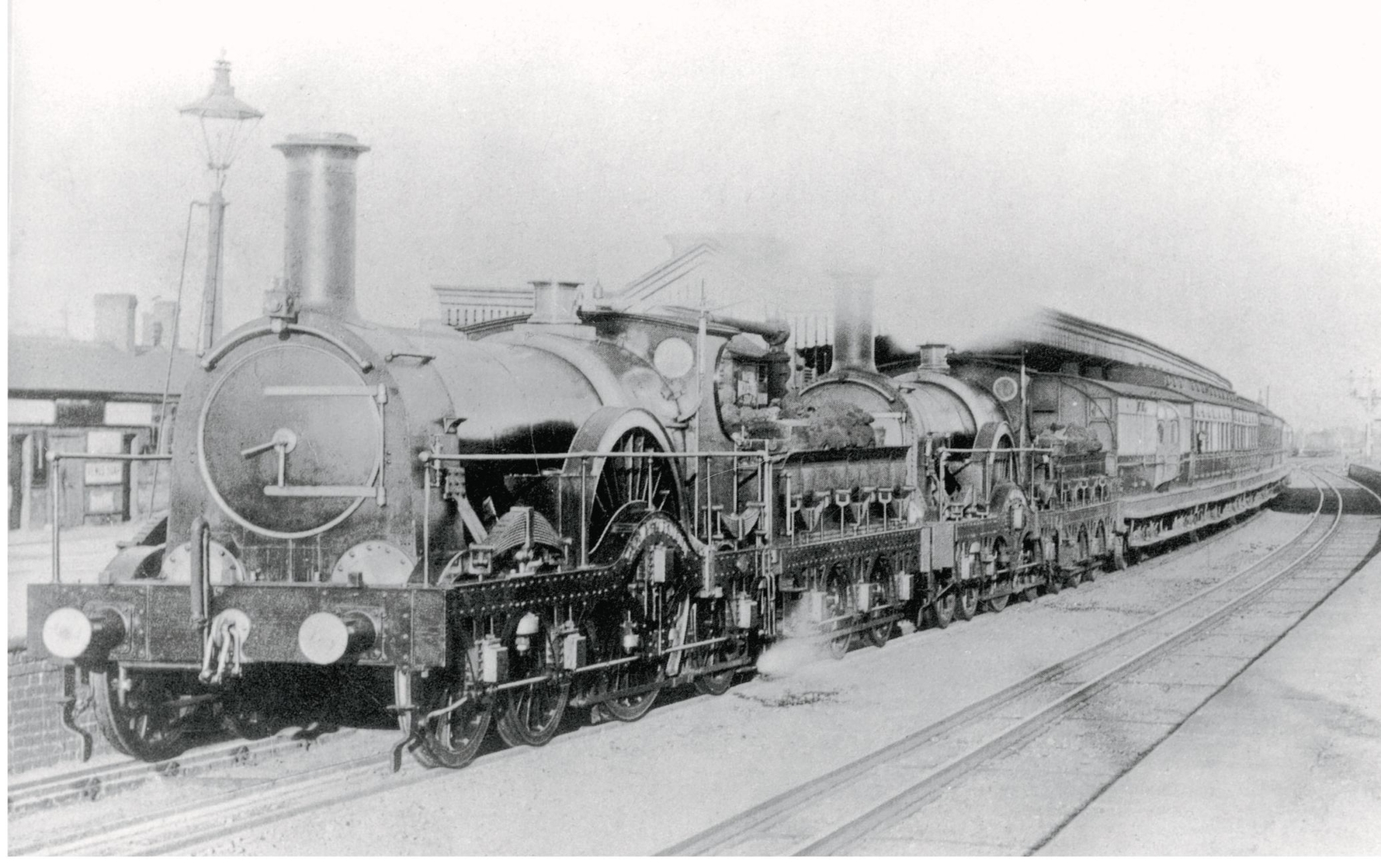

Rover class locomotives Great Western, an 1880 ‘renewal’ of the original, and Swallow, built 1871, head the ‘Flying Dutchman’ through Didcot in May 1892, the last month of broad gauge operation. GW TRUST COLLECTION

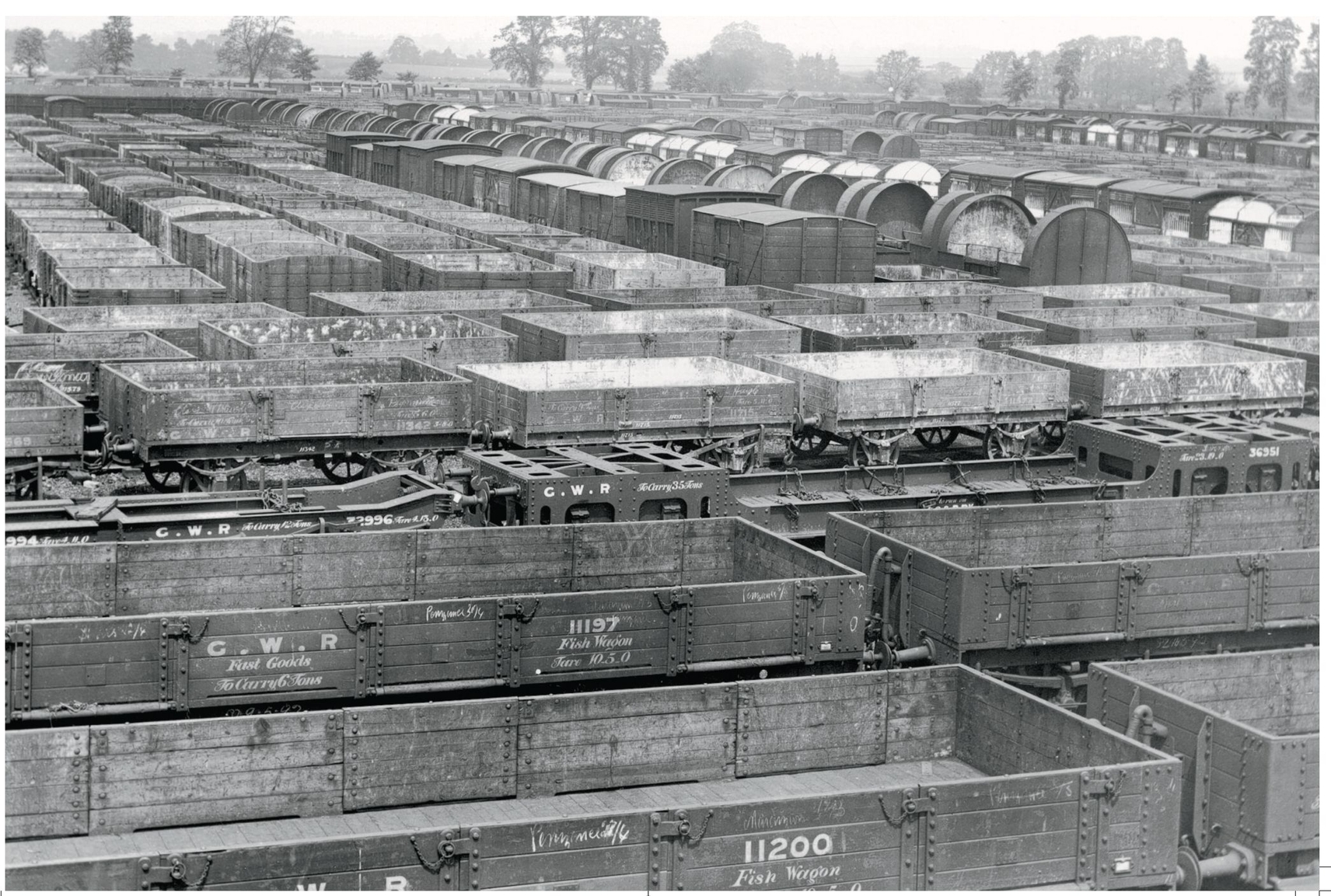

Temporary sidings at Swindon were crammed with broad gauge wagons following the conversion of the last part of the GWR system to standard gauge. GW TRUST COLLECTION

Incidentally, broad gauge had also been employed on a far smaller scale on several Victorian harbour and breakwater railways, at Holyhead, Portland and Port Erin, no doubt because of their capacity to carry bigger loads to and from ships as well as the huge stone blocks used in their construction.

These were mainly the work of engineer James Meadows Rendel (1799-1856) or inspired by his designs. He also collaborated with Isambard.

Brunel’s gauge may have been the widest of any passenger-carrying system in the world, but it was not the widest to be used for freight. For instance, the Dalzell Iron & Steel Works in Motherwell was once supplied with three new Barclay 0-4-0 saddle tanks to haul ladles of molten slag on an internal 10ft11in gauge line.

The 7ft 0¼in gauge dream did not die out entirely in 1892. The engineer W Collard published plans in 1928 for a Brunel broad-gauge railway from London to Paris via a channel tunnel. What if it had been built? What if we still had broad gauge today?

Hindsight may well seem to support Brunel and Gooch’s convictions. Today’s larger, faster trains could have benefited from the increased flexibility of a broad-gauge network without narrow bridges and low headroom.

On the other hand, would greater operating and maintenance costs have pushed even more customers towards cheaper road transport?

One very unsavoury convert to the Brunel vision drew up plans for a Europe-wide railway system with tracks three metres wide – 9ft 9ins – in the 1940s.

Monstrous locomotives would haul carriages, each capable of carrying hundreds of passengers, and wagons built to take ships, across a network of lines radiating from Berlin to Paris, Moscow and beyond, serving the Fatherland’s newly conquered territories in a post-war world and ensuring its armies could be mobilised at a moment’s notice.

Thankfully this railway never had the chance to be built, for the would-be architect of it was none other than Adolf Hitler.

Brunel broad gauge is still in commercial use in Britain today – at one location. At the Environment Agency depot in Reading, an electric crane runs when required on a 151ft-long track.