Chapter 20

FIRE FLY

Brunel’s Steam Dream Reborn

As chief mechanical engineer of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway, William Stanier designed some of the finest locomotives in the world. Those who have seen one of the surviving examples, express passenger engine Princess Coronation 4-6-2

No 6233 Duchess of Sutherland in action – now a preservation icon, which hauled the Royal Train in 2002 and 2005 – will need no convincing here.

However, when it came to heritage matters, Stanier was nothing less than a vandal of the worst order.

For it was he, long before Henry Ford, who effectively declared that, ‘history is bunk’ – and consigned museum pieces to the scrapyard.

After the end of the broad gauge, the GWR cut up all but two of the 7ft 0¼in gauge engines.

Spared the scrapyard were pioneer North Star, which had been preserved after withdrawal in 1871, and celebrity Iron Duke class 4-2-2 Lord of the Isles, the Great Western Railway’s exhibit at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The pair appeared at various exhibitions, Lord of the Isles even appearing at Chicago in 1893 and Earls Court in 1897.

The GWR continued to expand, and in the early years of the 20th century, space at Swindon where the pair were stored was at a premium.

The two survivors were offered to a succession of museums, but none could find the space to display them.

Stanier, who was then in charge of Swindon Works, decided – in the absence of chief mechanical engineer George Jackson Churchward, who was away on holiday at the time – to cut them up. In a stroke, Stanier all but wiped out broad-gauge heritage from the face of the earth.

Fire Fly runs along a typical stretch of 1850s broad gauge. GWS

On his return, Churchward was understandably horrified, and salvaged many of the parts of North Star, but could save only the driving wheels from Lord of the Isles.

Stanier had no regrets, and repeated his hooligan approach to history when he oversaw the LMS, which in the late 20s had begun to safeguard examples of its most noteworthy classes. Four locomotives, an old Midland Railway 0-6-0, 1856-built No 401, which was withdrawn in 1925 and restored in 1929, Midland 156 class 2-4-0 No 156 (LMS was numbered 1), and Johnson 0-4-4T No 1226, which harked back to 1875, both set aside on withdrawal in 1930, and North London Railway 4-4-0T No 6 were all earmarked for preservation.

However, shortly after he arrived from Swindon, Stanier ordered all four to be scrapped in 1932.

Clearly he was a man who was interested only in the future (and what a shimmering future he brought to his railway) and there were many who shared his contempt for the commonplace and obsolete. Why would, for instance, anyone want to preserve a 1970s fridge or washing machine for posterity, when it would only serve to take up space, and a modern one could probably do the job more efficiently?

Still, this was not excuse for his actions, which must, even by the standards of the day, seem grossly irresponsible. The concept of railway preservation, the saving of pioneering items for the benefit of future generations, dates back almost to the dawn of the steam railway.

The early Victorians took more care than might at first be supposed to set aside the very earliest locomotives. Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s GWR from Paddington to Bristol was still two years in the future when the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway pioneer Invicta (the first to work on a public railway south of the Thames) was set aside in 1839, at first kept as a curio in a public park, and now on view in Canterbury Heritage Museum in Stour Street.

Of today’s survivors, the next to be retained would be the pioneer from the Stockton & Darlington Railway, Locomotion No 1, which was preserved in 1857.

Sadly, Richard Trevithick’s 1804 locomotive did not make it. After years of use as a stationary boiler, it ended up among a pile of scrap purchased by the London & North Western Railway. It was put on one side for short time with preservation in mind, until locomotive superintendent, William Webb had a change of heart, and it went to the blast furnace of LNWR’s own steelworks.

The GWR was, along with the other major companies of the day, invited in 1925 to take part in celebrations to mark the centenary of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, the world’s first public steam-operated line. Suddenly, the directors woke up and realised that they could display no locomotive from their formative years.

The salvaged parts of North Star were tracked down and used in the building of a replica at Swindon. It is this locomotive that is today exhibited inside STEAM – Museum of the Great Western Railway at Swindon, although it has never been able to move on its own.

The GWR continued to be unconcerned by any need for preservation, except in the case of No 3440 City of Truro, when it was withdrawn in 1931. The locomotive, which the GWR claimed had been the first in the world to top 100mph, is now part of our national collection and under the National Railway Museum returned to the main line in time to celebrate the centenary of that run in 2004.

Despite the considerable celebrations in 1935 marking the GWR’s own centenary, the company showed no interest in salvaging any large locomotive relic from the broad-gauge era. South Devon Railway 2-4-0 saddle-tank Prince, which had been built in 1871, was among the locomotives converted to standard gauge in 1893 and soldiered on for another six years before its withdrawal in 1899. After that, it was used as a stationary boiler in Swindon Works.

Its rediscovery led to renewed interest in the broad gauge, but nonetheless the GWR saw fit to scrap it.

From late Victorian times, it was clear that the general public had a greater interest in railways than merely travelling on them. The early, crude model trains proved very popular and led to the establishment of manufacturers like Hornby, Marklin and Bassett-Lowke, while miniature, live steam lines at seaside resorts, in parks and pleasure gardens did a roaring trade.

The idea of private individuals taking over a railway to run it independently, or as a place on which heritage traction could be operated (as opposed to being kept in a museum on static display) may have its origins in the abortive attempts to revive the 3ft gauge Southwold Railway in Suffolk after it closed in 1929.

However, the first railway in Britain, and indeed the world, to be revived by volunteers was the 2ft 3in gauge Talyllyn Railway at Tywyn in central Wales, when a Birmingham-based group, led by transport historian Tom Rolt, took restarted public services after it was set to close.

This example was followed in 1954 by volunteer groups who saved the Ffestiniog Railway and Welshpool & Llanfair, and the Bluebell Railway in Sussex followed these narrow-gauge revivals in 1960, closely behind was the aforementioned Middleton Railway at Leeds – creating Britain’s first two standard gauge preserved lines.

The blue touch paper was lit, and we now have more than 100 operational preserved railways in Britain, most offering the chance to travel behind steam, a form of traction finally discarded by British Railways in August 1968. Numerous classic locomotives from the steam age can now be seen again, polished to perfection by the groups who own and run them.

The driving force behind many volunteers is often the desire to recreate scenes from their own ‘golden age’, when trainspotting was a hugely popular activity among schoolboys of the 50s and 60s, to be found during the long summer holidays at every station and overbridge with their Ian Allan spotters’ guides.

As a result, many preserved lines reflect the railways of the post-war period, with others harking back to the Big Four years of 1923-1948 and a select few specialising in the time before them, the pre-Grouping era.

It has been said that if all the preserved railways in the UK were laid end to end, they would stretch from London to Glasgow and beyond. Maybe so, but for so long there was one major quadrant of British railway heritage missing from the preservation portfolio – Brunel broad gauge.

It was in the early 1980s, however, that fresh green broad-gauge shoots began breaking through the soil in the city that Isambard had made his own – Bristol.

Retired Royal Navy Commander John Mosse, was working as consultant architect to British Rail on the restoration of Temple Meads Old Station in 1981, when he came up with the idea of building of a new Fire Fly, a replica of the first one, but nonetheless the 63rd member of the ground-breaking class of 2-2-2s.

He soon found that many others shared his enthusiasm, including Leslie Lloyd, then general manager of the Western Region, and his chief mechanical and electrical engineer John Butt.

They were soon joined by several retired railway engineers including SAS Smith, who as manager of Swindon Works had overseen the construction of Standard 9F No 92220 Evening Star, BR’s last steam locomotive, in 1960.

The big breakthrough came when Daniel Gooch’s original drawings for the Firefly class were found at Paddington.

By 1982 the Firefly Trust was established and fundraising began.

It became clear that much of Gooch’s specification would be unacceptable in the safety-conscious modern world, and Gooch’s design would need to be modified.

Enforced changes would include the braking, which on the original was not on the engine but on one side of the tender only, and the boiler, which Gooch had designed to be the main longitudinal strength member, while additionally taking all the horizontal drag loads. Nor was there provision for boiler expansion.

The frame was redesigned to act as a support to the boiler rather than the other way round, with boiler expansion being permitted by the introduction of a dummy firebox, which would also take the drag loading. The frame, although considerably stronger than that of Gooch’s, would still be true to the appearance of the original.

By 1987, sufficient money had been raised to allow building to start, as a Manpower Services community project, backed by Bristol City Council.

Within a year, the terms of the Manpower Services training schemes were amended and the council decided against further participation.

At the same time, the trust’s workshop on the banks of the River Avon was declared unsafe and the occupants were forced to leave. The uncertainty of the future of the project resulted in the loss of a large loan.

Help was at hand in the form of the Great Western Society, a group dedicated to the preservation of everything from the company whose name itself may have been suggested by Isambard. The society offered space in its new locomotive workshop at Didcot Railway Centre, and soon the partly built engine had arrived.

The 21st-century Fire Fly in action on its short running line at Didcot Railway Centre. FIREFLY TRUST

Great Western traction a century apart: the new Fire Fly stands at the interchange station in the bay opposite 1930s pioneer diesel-railcar W22. GWS

Wheelsets for the new Fire Fly await fitting at Didcot. FIREFLY TRUST

Firefly Trust chairman takes on the role of Isambard Brunel as the new Fire Fly is officially launched at Didcot. GWS

Cmdr John Mosse about to put the axle into the first Fire Fly wheel at Swindon in March 1996. FIREFLY TRUST

Fire Fly takes on water at Didcot. Its coach is representative of third-class travel in the 1840s. GWS

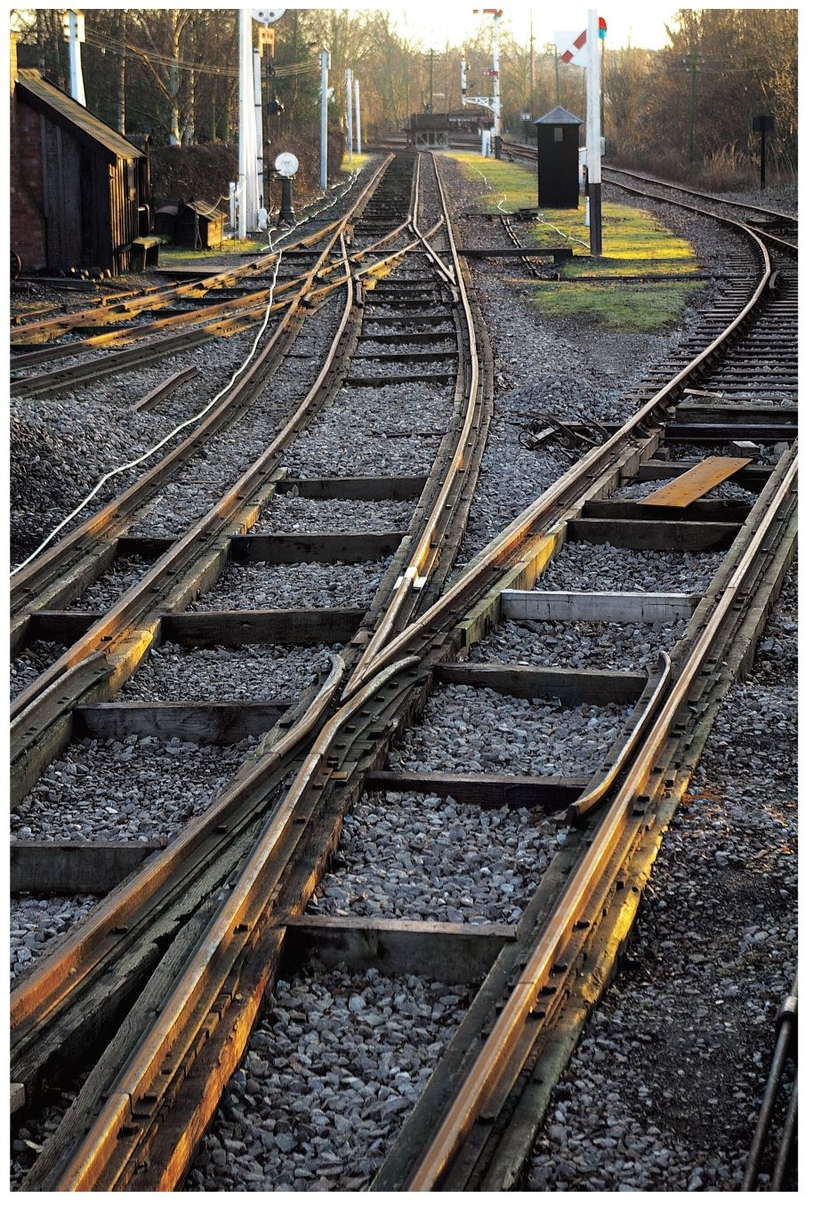

Mixed-gauge pointwork on the Didcot broad-gauge demonstration line. ROBIN JONES

Meanwhile, the National Railway Museum had commissioned a working replica of the first Iron Duke in time for the Great Western 150 celebrations in 1985, together with a matching open carriage.

It was built using parts from two standard gauge Austerity 0-6-0 saddle-tanks, a type of basic but powerful locomotive designed for mass production during WWII, and with nearly 100 examples of them in preservation, the potential loss of two was considered to be no detriment to railway heritage.

The new Iron Duke was built using modern materials and methods to exactly resemble Gooch’s 1847 drawings, complete with exposed wooden lagging (from 1848 onwards, sheet iron was added over the lagging and painted to match the tender).

A short demonstration running line was built at the York museum to allow it to run, and Didcot also built its own broad-gauge track, complete with mixed-gauge section and the transhipment shed from Burlescombe, where in the days of the break of gauge, passengers and goods had to be switched from one train to another.

The National Railway Museum’s replica of Iron Duke. NRM

Retired airline pilot Sam Bee took over as chairman of the Firefly Trust in November 1998, following the untimely death of Cmdr Mosse.

Following the delivery of a new boiler from Israel Newton & Sons of Bradford and successfully steamed, the new Fire Fly, built for a cost of around £200,000 over 23 years, not the 13 weeks and £1735 like the original, ran under its own power for the first time at Didcot on 2 March 2005. It was the first new main line steam locomotive to be built in Britain since Evening Star 45 years before.

Fire Fly’s public debut came at the railway centre on 30 April 2005, launched into traffic by veteran of film, TV and stage, Anton Rogers, to rapturous applause.

The spirit of Brunel and Gooch had returned at last.

Yet will Fire Fly ever run anywhere apart from on Didcot’s short demonstration line?

Will there ever be a fully fledged broad-gauge railway in the preservation world?

Fire Fly simmers alongside the Burlescombe station platform at Didcot. FIREFLY TRUST

Previous suggestions to add a broad gauge running rail to today’s South Devon Railway between Buckfastleigh and Totnes, a line originally built to 7ft 0¼in gauge, and on the Cholsey & Wallingford Railway near Didcot, came to nothing.

However, as the phenomenal interest shown in the 2006 celebrations to mark the bicentenary of Isambard’s birth have shown, there is ever-increasing admiration on a global scale for his many unique works and achievements. Rather than be ‘just another preserved steam line’ a Brunel broad-gauge railway would allow a fuller glimpse into that fantastic age of change, and could become a major crowd puller or the basis for a Victorian theme park.

To bring such a scheme to reality, however, it would take lorryloads of cash, and an entrepreneur who is broad minded in more ways than one. Much like Isambard Kingdom Brunel.