Racial profiling affects people of color in all aspects of life, including education.

Chapter 3

Contemporary Inequality

Racial profiling in the United States is an outgrowth of institutional racism, the patterns of racial bias that are woven into every facet of American life. The racial biases that underlie institutional racism are not always overt and may even be unintentional. (These are often called implicit biases.) Nevertheless, entrenched societal racism pervades education, employment, housing, health care, politics, business, and the criminal justice system. It is often most visible in the ways in which systematic racial profiling results in fewer opportunities, more health risks, and higher poverty rates for people of color than for white Americans. People of color are substantially more likely than white people to live below the poverty line. (The poverty line is a government measure of household income below a certain level of which families qualify for government assistance programs.) For instance, the Economic Policy Institute reports that 27.4 percent of African Americans live in poverty, compared to 26.6 percent of Latino Americans and 9.9 percent of European Americans. The disparity between black Americans and European Americans is even greater among children, with 45.8 percent of black children and 14.5 percent of white children under the age of six living in poverty. This widespread economic inequality arises from—and perpetuates—a cycle of racial profiling in which institutions and individuals perceive people of color as less intelligent, underperforming, and criminally minded.

Profiling in the Classroom

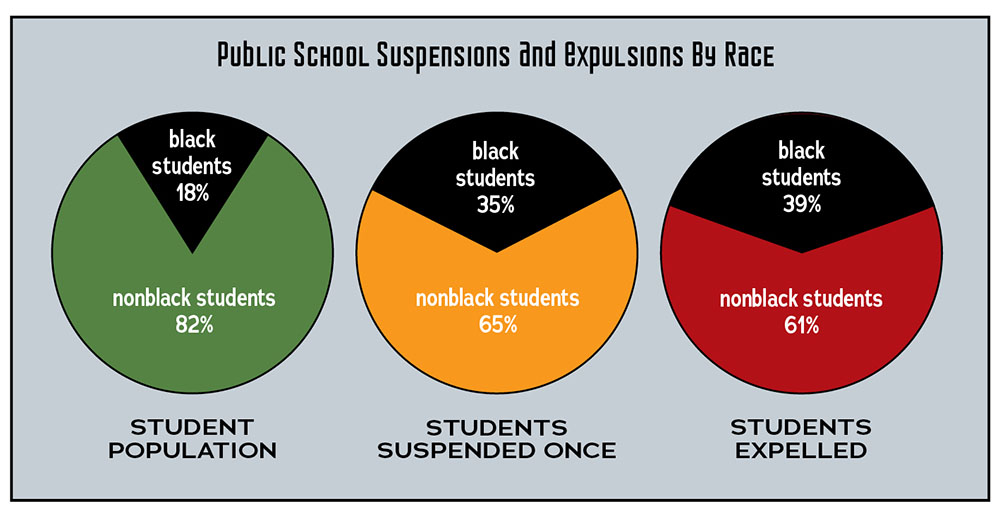

As early as preschool, students in the US public school system encounter unequal treatment based on race. According to a 2014 study by the Department of Education and the Department of Justice (DOJ), black students make up only 18 percent of children enrolled in US preschools. Yet they represent 48 percent of preschoolers who received more than a single out-of-school suspension. The report also found that all students of color, regardless of grade level, face a higher likelihood of being suspended from school than do white students and that black students are suspended or expelled three times more often than white students.

Other children of color faced higher rates of discipline too. For example, American Indian children make up less than 1 percent of public school students in the United States but represent 2 percent of out-of-school suspensions and 3 percent of expulsions. The report notes that disparity is “not explained by more frequent or more serious misbehavior by students of color.” Thena Robinson-Mock of the Advancement Project—a civil rights advocacy organization—emphasizes that the majority of disciplinary actions are for relatively small offenses. “There’s this idea that young people are pushed out of school for violent behavior, and that’s just not the case—it’s things like truancy [missing school], cellphone use, not having supplies, and uniform violations.” Time out of the classroom causes students to fall behind in their schoolwork. Faced with repeated punishment and a lack of support from teachers and administrators, many students of color internalize the idea that they are unlikely to succeed academically, and their performance slips to match this expectation.

In a 2012 nationwide study of seventy-two thousand schools in seven thousand districts, the US Department of Education found that African American students are disproportionately likely to be suspended or expelled.

Beyond the greater likelihood of institutionalized punishment, students of color face other forms of racial bias in the classroom. For instance, studies show that teachers—particularly white teachers—recommend black and Latino students for gifted programs at much lower rates than white students. Similarly, some school districts have put students of color into remedial or special education courses even though their intelligence is on par with that of their white peers. This too fits into an institutionalized profile of children of color that assumes they are intellectually inferior to white children. All these factors contribute to a lower high school graduation rate for students of color than for white students.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, high school graduation rates are consistently lower for students of color than for white students. The top chart at right shows data from the 2013–2014 school year. Similarly, young people of color are less likely than white people to enroll in college, as shown by the data from the 2014–2015 school year. Racial profiling by secondary school faculty and staff can contribute to lack of opportunities for students of color to succeed academically.

Such inequalities persist in higher education, where students of color often face profiling from their white peers. Blatant profiling, such as the unofficial but systematic exclusion of people of color from certain parties and student groups, has been reported at numerous campuses. Subtler race-based attitudes and judgments are even more common. Some white students may assume that students of color were admitted to college to fulfill a diversity quota rather than because of their academic qualifications. Others may hold negative stereotypes about the lifestyles of people of color.

Olevia Boykin, a black student at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, noticed that her white fellow students “have this image of ghetto black people as portrayed in the media.” Professors and other authority figures may consciously or unconsciously hold these assumptions as well, especially given that the vast majority of college and university faculty members are white. A 2015 report by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) found that people of color (excluding people of Asian descent) make up only 8 percent of the faculty at the nation’s four-year colleges and universities. Black students at colleges and universities are more likely to face accusations of cheating than white students. And in general, students of color feel that others judge them based only on their race. Mariama Suwaneh, a black Latina student at the University of Washington, recalls the pressure of being the only student of color in a lecture class with hundreds of students: “I do feel like every time I raise my hand, I speak for all black people. If I say something that seems out of place, or something that doesn’t sound as intelligent as another student, that’s a knock on all students of color here on campus.”

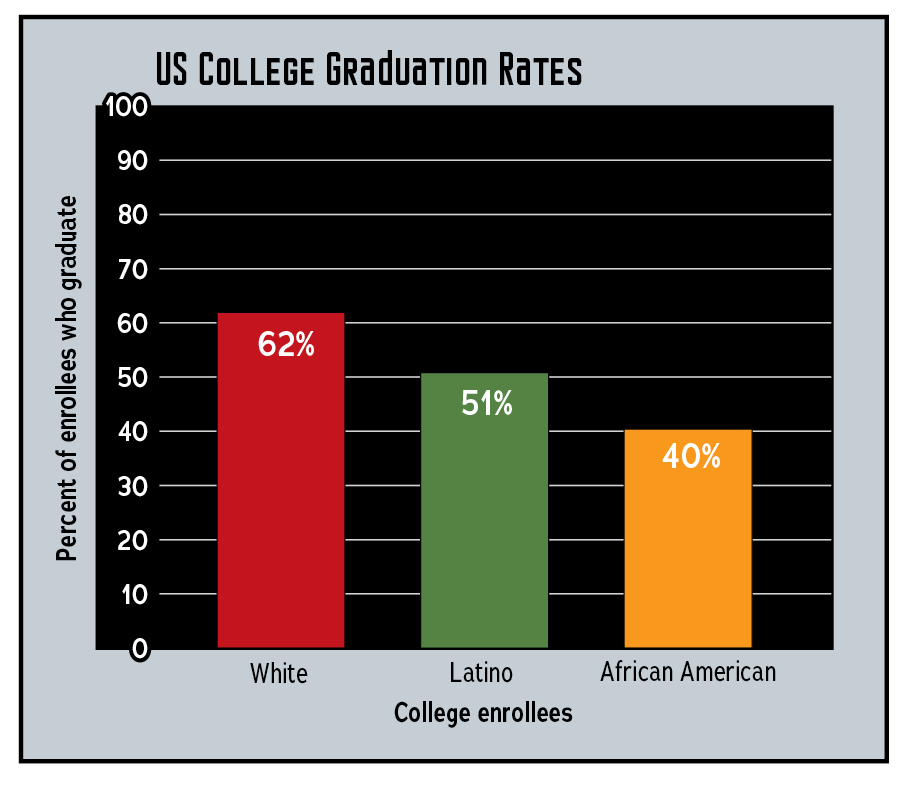

Racially biased attitudes and treatment can lead to feelings of isolation and stress. These are among the many factors that make students of color less likely than white students to graduate from two- and four-year colleges. (Other factors include financial difficulties and the failure of high schools to prepare students of color for the college experience. They also include conditions linked to poverty, low expectations, and other aspects of institutionalized racial bias.)

For students of color who graduate from four-year programs and go on to graduate school, stereotyping and discrimination continue at the highest levels of education. A 2014 study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology found that college and university professors who received student inquiries about doctoral (PhD) research opportunities were most likely to respond to students whose names suggested that they were white men. Brandon, a graduate student of color studying applied physics, recalls, “I was trying to talk to [a professor] about his research and his response was, ‘Well, I didn’t think your kind would be interested in this kind of research.’”

Students of color who enroll in higher education often struggle to succeed in subtly uncomfortable or overtly hostile environments. Many encounter the persistent expectation, based on their race, that they will underachieve. A lack of support from peers, faculty, and staff can help turn these expectations into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Students of color have significantly lower college graduation rates than white students—as shown by 2010 data from the Education Trust, an advocacy group for disadvantaged students.

Johnny R. Williams has a degree from a prestigious university and a strong professional background. But when he found himself struggling to land interviews for jobs, he revised his résumé with a specific goal—to make it less obvious that he is black. For example, he removed a reference to his membership in an African American association. “If they’re going to X me, I’d like to at least get in the door first,” he explained.

Like Williams, many people of color face obstacles in employment related to racial profiling. A landmark 2003 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that applicants with names that suggest a black identity are called in for interviews less often than those with names that imply European American heritage. Other studies show that white applicants who have been convicted of felonies are as likely or even more likely to be called back for interviews as black applicants without criminal records. Employers also tend to view black applicants as more likely than white applicants to use drugs, as well as less likely to have the necessary work ethic and interpersonal skills to perform well.

These profiling trends suggest an institutionalized perception of workers of color as less qualified than white applicants. Profiling helps explain why—according to a study published in the Journal of Labor Economics—white, Latino, and Asian managers hire more white and fewer black applicants than black managers do. Daniel L. Ames, a researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, explains that this kind of bias is often completely unconscious. “If you ask someone on the hiring committee, none of them are going to say they’re racially biased. They’re not lying. They’re just wrong.”

Intentional or not, racial bias plays out on the job as well. Many workers of color report that white coworkers tend to doubt their qualifications and expect them to underperform, reacting with obvious surprise when they excel.

Race-based assumptions can result in fewer opportunities for people of color in the workplace. Nationwide, African Americans are less likely to be promoted and more likely to be laid off than white employees. Veterinary immunologist Gabriela Calzada had a similar experience when she applied for a coveted job. “I had all the qualifications to get it,” says Calzada. “I think they didn’t give it to me because I’m Hispanic. . . . [The successful applicant] only had a bachelor’s degree, and I have a Ph.D.” Thirty-three percent of workers in management positions are white, while 22 percent are black and 14 percent are Latino. And 90 percent of the nation’s chief executive officers—the power players in corporate America—are white.

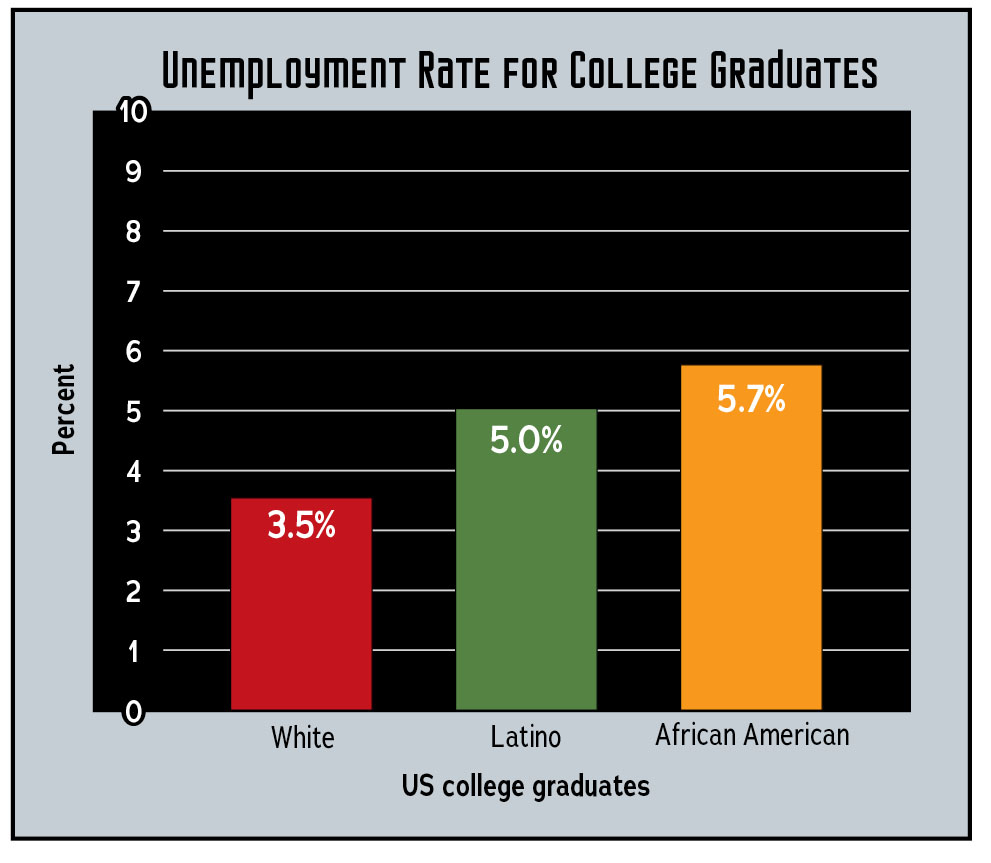

College graduates of color are more likely to be unemployed than their white counterparts, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics from 2013.

Income Inequality

People of color face a significant wage gap: a disparity between what they earn and what white Americans earn. The typical (median) African American household earns about 40 percent less than the typical white household. Factors such as a lower level of education and other barriers to higher-paying jobs contribute to this gap, but in some industries, people of color earn less than white coworkers with equivalent jobs. For instance, a 2014 analysis by the American Institute for Economic Research revealed that in the computer technology industry, Latino workers earned an average of $16,353 less than non-Latino workers in the same types of jobs. Black workers earn an average of $3,656 less per year than white workers, while Asian Americans earned $8,146 less than white workers. The same study found that highly skilled black finance workers earned $20,691 less per year than white workers with the same job. Highly skilled Latino workers earn $9,328 less than non-Latino workers.

This statistically lower earning power makes it much more difficult to support a family and to save money for future goals and needs. In 2013 a national study reported a $131,000 difference between the net worth of a typical white family and that of a typical black family. Studies show that about 25 percent of African American families have less than $5 of savings, compared to $3,000 for the poorest 25 percent of white families. If these families face unexpected emergencies such as serious illnesses or the loss of a job, the effects can be devastating.

Studies also show that black families are more likely than white families to be sued for their debts. The process often begins with debt collection agencies, which seek out people who owe money to credit card companies, medical providers, retailers, utility companies, and other creditors. Collection agencies and creditors themselves can sue debtors for failing to repay the money they owe. (People in dire financial situations can file for bankruptcy, but depending on the type of bankruptcy, they may remain responsible for certain debts or are vulnerable to future financial troubles that can create fresh debts. Many debtors also lack reliable resources to help them understand how to file for bankruptcy.) If a court decides in favor of a debt collector, the collector may take money out of the debtor’s paycheck as part of a repayment plan or confiscate property connected to the debt (known as repossession). Debtors who violate a court order or fail to appear in court can face jail time.

All these consequences can drive people into even deeper debt. And race plays a part in how courts typically decide a debtor’s case. A 2015 study by the investigative journalism organization ProPublica found that courts ruled against debtors about twice as often in mostly black communities as they did in mostly white areas. As one of the study’s authors noted, “If you are black, you’re far more likely to see your electricity cut, more likely to be sued over a debt, and more likely to land in jail because of a parking ticket.”

“White Tenants Only”: Housing and Loans

Celeste Barker, an African American woman living in Ohio, was interested in a townhouse she’d seen listed for rent. But when she went to the rental office for more information, the property manager told her the home was no longer available. Barker reported the incident to a local fair housing group, which assigned a white person and a black person to call the agency about the same property. The property manager set up an appointment for the white caller to view the house the next day. He told the black caller that the house was unavailable.

Barker’s experience reflects the challenges that renters and buyers of color confront when trying to find homes. A 2012 Housing and Urban Development (HUD) report found that people of color seeking to rent apartments and buy homes were told about fewer available properties than white people, sometimes even being told (falsely) that nothing was available.

The same pattern applied when people toured units, with real estate and rental agents showing fewer options to people of color. In some cities, studies have also found that landlords are more likely to conduct background checks on renters of color than prospective white tenants. One white landlord in New York City confessed to a New York Magazine reporter in 2015, “In every building we have, I put in white tenants. They want to know if black people are going to be living there. . . . They see black people and get all riled up, they call me: ‘We’re not paying that much money to have black people live in the building.’ If it’s white tenants only, it’s clean.” Discriminatory profiling against buyers and renters of color helps explain why even wealthy Americans of color tend to live in lower-income neighborhoods than white Americans.

When home buyers of color seek home loans to help cover the cost of their purchase, they encounter roadblocks that echo twentieth-century redlining practices. In 2013 black and Latino home buyers were denied loans more than twice as often as white buyers with similar financial profiles. This is one reason that home ownership in the United States is lower among people of color than among white people. In 2016, 42 percent of black households and 45 percent of Latino households owned homes, compared to 72 percent of white households. Studies also show that people of color who do secure home loans often pay higher interest rates than white borrowers—even white borrowers with similar economic footing and credit history. Partly as a result of these discriminatory practices, black people are more than five times as likely as white people to live in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty—areas that also typically have less access to high-quality schools and other resources.

In general, people of color face greater difficulty obtaining loans than their white counterparts do or they may be given less desirable loan terms. For example, reports show that when black and Latino car buyers seek loans to buy automobiles, creditors tend to charge them higher interest rates than white borrowers. Similarly, a 2014 study focused on entrepreneurs of color who sought loans to start or improve small businesses, comparing their experiences to those of white borrowers with similar financial profiles. This study found that borrowers of color faced more questions about their finances, received less information about their options, and were less likely to be offered help in filling out applications. The study quoted an anonymous black man who spoke about the impact of these challenges: “My self-esteem and confidence are strong, and yet I’m being denied [a loan], so it makes me feel bad about myself, bad about my business. . . . You’re made to feel like [you’re] just not competent or capable. I feel very, very insecure.”

Barriers to desirable housing are one reason that families of color are more likely than white children to live in neighborhoods with fewer resources, higher crime rates, and a higher exposure to health risks. And because communities of color tend to have less political and socioeconomic power than majority-white communities, they often have little say in what types of industry and development take root around them.

People living in poor and heavily nonwhite neighborhoods tend to be in closer proximity to toxic waste dump sites, pollution-producing power plants, and other hazardous facilities. Even within the same community, people of color are more likely than white residents to be exposed to harmful air pollution and other health risks. For instance, a 2014 study by the University of Minnesota found that people of color are exposed to 38 percent higher levels of nitrogen dioxide than white people in the same town or city. Nitrogen dioxide—a pollutant produced by automobiles, construction equipment, and industrial operations—is linked to asthma and heart disease. Many communities of color, particularly Latino communities, also lack adequate water treatment and sewer services, which puts residents at risk for certain kinds of cancer, liver disease, and other potentially deadly illnesses. Between 1996 and 2013, communities of color filed 265 complaints with the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Civil Rights, claiming that nearby polluters had engaged in environmental discrimination. The EPA has dismissed 95 percent of these claims, the majority without any investigation. This greater likelihood of hazardous conditions, combined with the lower likelihood of intervention from authorities, is sometimes called environmental racism.

A prominent case of alleged environmental racism emerged in Flint, Michigan, in 2015. Flint is among the nation’s poorest cities, with 40 percent of the population living below the poverty line—and more than half the population is African American. In 2015 corroded water pipes leached dangerously high lead levels into Flint’s public drinking water supplies. Lead poisoning can have severe long-term health effects, especially for children. According to the World Health Organization, “Lead affects children’s brain development resulting in reduced intelligence quotient (IQ), behavioral changes such as shortening of attention span and increased antisocial behavior, and reduced educational attainment.” Michigan’s governor, Rick Snyder, commissioned a task force of experts to study the origins of the crisis in October 2015 and declared a state of emergency in January 2016.

In March the task force issued its report, which stated that government bodies at all levels had failed to respond appropriately to early reports of water contamination. According to the task force, Flint’s state-appointed managers had prioritized money-saving measures over public safety, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality had failed to recognize the problem soon enough, and the EPA had neglected to step in despite being aware of the contamination as early as April 2015. The report concluded, “Flint residents, who are majority black or African-American and among the most impoverished of any metropolitan area in the United States, did not enjoy the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards as that provided to other communities.” State representative Dan Kildee went a step further. Contending that unconscious racial bias often determines which communities receive the most government funding and attention, he said, “Places like Flint [with large black populations living in poverty] get written off.”

Lead-tainted drinking water sparked a health crisis in the poor, majority-black city of Flint, Michigan. Residents were forced to use bottled water after the contamination was revealed. Here, a young person brings cases of water to a Flint home.

“Racism without Racists”

With less earning power and more economic vulnerabilities, people of color occupy a less powerful position in US society than white Americans. In turn, these disadvantages reinforce a false impression that people of color are underachievers who simply lack the intelligence or the work ethic of white people. Profiling based on these misconceptions fuels a cycle of widespread inequality.

Sociology professor Eduardo Bonilla-Silva of Duke University in North Carolina describes the influence of these subtle racial biases as “racism without racists,” because many white Americans are unaware that racial bias is influencing their actions or shaping the systems in which they participate. “Instead of saying as they used to say during the Jim Crow era that they do not want us as neighbors [white people] say things nowadays such as ‘I am concerned about crime, property values and schools.’ . . . The ‘new racism’ is subtle, institutionalized, and seemingly nonracial.” People of color feel the consequences of these attitudes in every aspect of American life, from preschool to the professional world.

Communities of color traditionally receive few resources and little support from government and business institutions. Residents of American Indian reservations, for instance, often have very limited access to education, jobs, health care, and other infrastructure. This Oglala Lakota boy lives on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where about half the residents live below the poverty line.