Demonstrators in Los Angeles block traffic to protest racial profiling and police brutality. Protesters use raised hands, often combined with the mantra “Hands up, don’t shoot,” to invoke police killings of people of color.

In 2013 Trayon Christian, an eighteen-year-old college student, went shopping in New York City. He visited the high-end department store Barneys, where he bought a designer belt with his debit card. At the clerk’s request, he showed his ID. But a few minutes after he left the store with his purchase, two undercover police officers stopped him on the street. Christian says they asked to see his ID and look in his shopping bag, claiming that someone at Barneys had been concerned that Christian had used a fake debit card. “The detectives were asking me, ‘How could you afford a belt like this? Where did you get this money from?’” Christian recalled. The officers then arrested him, handcuffing him and taking him to the police station. Police released him about two hours later without pressing charges. Christian was outraged by both the NYPD’s behavior and the store clerk’s suspicions. “I brought the belt back to Barneys a few days later and returned it. I got my money back, I’m not shopping there again,” he said. “It’s cruel. It’s racist.” He went on to file a lawsuit against Barneys, accusing the company of racial discrimination and profiling. In 2016 Barneys settled the lawsuit by agreeing to pay Christian $45,000. As Christian’s attorney, Michael Palillo, put it, “His only crime was being a young black guy buying a $300 belt.”

Trayon Christian refused to accept racial profiling as an inevitable inconvenience and humiliation. Instead, he spoke out against his treatment and took action to prevent similar incidents from happening to others. Like Christian, many Americans are challenging the use of racial profiling by both private citizens and law enforcement. A 2015 poll by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights found that 57 percent of Americans support a ban on racial profiling by police and national security agencies (such as the FBI, the DHS, and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement). Elected officials, lawmakers, advocacy groups, and other concerned citizens are promoting public awareness of racial profiling and pursuing changes to the systems that support the practice.

At the national level, the DOJ announced in 2014 that it would enact new, stricter policies for federal law enforcement agencies (with exceptions for the FBI and US Border Patrol) with the goal of reducing racial profiling in the United States. Then attorney general Eric Holder noted, “I have repeatedly made clear that racial profiling by law enforcement is not only wrong, it is misguided and ineffective—because it can mistakenly focus investigative efforts, waste precious resources and, ultimately, undermine the public trust.”

Another proposed reform is the End Racial Profiling Act (ERPA), a bill introduced by Democratic legislators in the US House of Representatives and the US Senate on April 22, 2015. (The bill had been previously introduced in 2004, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2013 but failed to gain traction.) If approved by Congress and signed into law by the president, ERPA would outlaw racial profiling by all law enforcement officials, from city police to federal agents. One of the senators who presented the ERPA legislation, Democrat Ben Cardin of Maryland, spoke to Congress about the negative impact of profiling, saying: “While the vast majority of law enforcement work with professionalism and fidelity to the rule of law, we can never accept the outright targeting of individuals based on the way they look or dress. As a matter of practice, racial profiling just doesn’t work and it erodes the trust that is necessary between law enforcement and the very communities they protect.”

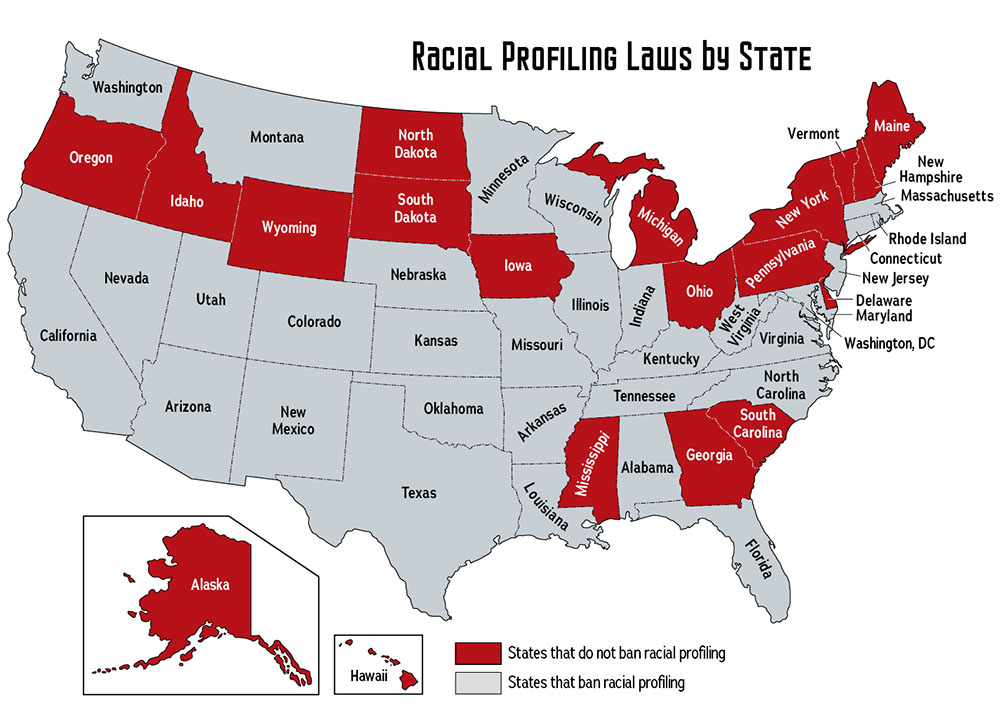

At the state level, reforms focus on enforcing existing anti-profiling laws through increased standards of transparency and accountability for police departments. In late 2014, the NAACP reported that twenty US states do not have laws that explicitly ban racial profiling. Of the thirty states that do prohibit profiling, none have provisions that are specific or extensive enough to meet the NAACP’s standards. In 2015 a few states moved to toughen their anti-profiling laws. For instance, in August 2015, Maryland expanded its anti-profiling law, which bans racial profiling at traffic stops. The state’s attorney general, Brian E. Frosh, issued new guidelines that prohibit the use of race or ethnicity as a factor in any police decisions—not just traffic stops—and prohibit profiling based on other identifying factors such as national origin and religion. In October 2015, California governor Jerry Brown signed into law the Racial and Identity Profiling Act.

Some states have no legislation specifically banning racial profiling by law enforcement. Other states ban the practice in broad terms but offer few guidelines for what qualifies as an instance of profiling. Consequences for illegal profiling also vary on a state-by-state basis.

The law requires California law enforcement officials to consistently report information on every stop they make—including the race of the person stopped and what charges or other actions, if any, resulted from the stop. Opponents of the law say the data will be of little use, as it won’t provide any objective insight into what officers are thinking as they conduct stops. Furthermore, some dislike the idea of encouraging officers to pay attention to race. “If you think about it, this bill actually encourages racial profiling by requiring officers to report what they perceive to be the race, ethnicity, gender and age of the person they stopped,” says Roger Mayberry, president of the California Fraternal Order of Police.

Advocates, on the other hand, say this data will provide statistical evidence of where profiling is happening and how pervasive it is, paving the way for reforms. Conversely, data that indicates equitable treatment of citizens will reinforce police departments’ claims of impartiality, notes David Harris, a scholar of police behavior at Pittsburgh University School of Law. Data that shows no evidence of racial profiling “enables the police department to say to the public, look, we looked at the data and no, we don’t have this problem.”

In Arizona, Latino activists are pushing for similar legislation. “We want data,” says Phoenix-based anti-profiling advocate DeeDee Garcia Blasé. “We want statistics. We want to hold the Phoenix Police Department, the Maricopa County Sheriff’s [Office], all the local law enforcement agencies accountable.”

Individual cities are also implementing changes. In June 2016, in response to public outcry over police shootings of black citizens, Chicago leaders introduced a groundbreaking policy shift. Chicago became the largest city in the country to adopt a policy for publicly releasing video footage of police shootings and other excessive force incidents. Footage must be released within sixty days of an incident, a sweeping change in a city known for the distrust between police and citizens of color. Local anti-profiling and anti-police-brutality advocates praised the policy as a step toward rebuilding public confidence in the police department. Some think the policy could serve as a blueprint for other cities around the country.

Activists urge police departments to require on-duty officers to wear body cameras that record stops, arrests, and other actions. Like cell phone videos taken by bystanders, body cameras have brought clarity to some cases that involve conflicting testimony. One case that highlighted the potential impact of body cameras was that of Samuel DuBose. On July 19, 2015, University of Cincinnati police officer Ray Tensing pulled over Samuel DuBose for a missing front license plate. During the course of the traffic stop, after DuBose failed to find his driver’s license, Tensing started to open the car door, telling DuBose to step out. DuBose instead closed his door and started the car. Tensing then shot DuBose in the head, killing him. Afterward, Tensing said that he had fired because he felt he was in danger of being run over by DuBose’s car and believed his own life was at risk.

Footage from Tensing’s body camera revealed that while DuBose did close his door, his car had barely moved when Tensing shot him. DuBose’s hands were visible, and Tensing appeared to face no threat to his life. After viewing the footage, Joe Deters, the prosecuting attorney for Hamilton County, Ohio, remarked, “This office has probably reviewed 100 police shootings, and this is the first time we’ve thought, ‘This is without question a murder.’” An investigatory report also stated that while DuBose was in the wrong when he closed the car door, “Tensing set in motion the fatal chain of events that led to the death of DuBose.” Ultimately, Tensing was fired from his job and charged with murder. The footage from his body camera was the key to both of those decisions.

Sensitivity and bias training is another way individual police departments can address racial profiling issues. In 2014, for example, the Omaha Police Department in Nebraska began implementing a training program that helps officers recognize and reduce their unconscious biases. “Profiling is something that won’t be tolerated,” says Omaha police chief Todd Schmaderer. “We take complaints very seriously.” The move drew praise from the ACLU of Nebraska, whose director, Danielle Conrad, said, “This is the exact kind of training we have been advocating for.” Dozens of other police departments across the nation have adopted similar training programs, which use role playing and group discussions to address implicit bias.

In addition to police reforms, activists have pushed for sweeping changes at all levels of the criminal justice system. To address racial disparities in sentencing and incarceration rates, advocates call for more community-based alternatives to incarceration; educational opportunities and mental health support for inmates to improve their chances of reintegrating into society after release; and the early release of inmates who have committed nonviolent, low-level crimes. One step toward reform came in 2010, when the US Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA). The law shortened mandatory minimum sentences for crack cocaine offenses, which disproportionately affect people of color. Numerous advocacy groups urge the federal government to reduce the sentences of prisoners already serving time for these offenses. According to Marc Mauer, the executive director of the criminal justice nonprofit group the Sentencing Project, “The challenge for both policy makers and the public is to build on these developments and to think creatively about ways of enhancing both public safety and racial justice.”

Taking to the Streets

Along with political and legal initiatives, independent organizations and individuals are working to combat racial profiling and racism. While not all of these groups and individuals are focusing exclusively on ending racial profiling itself, they share the goals of recognizing and lessening prejudice and discrimination in the United States.

The 2012 killing of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin sparked widespread sorrow and anger across the nation. The violent deaths of other people of color, including Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Freddie Gray, prompted more Americans to speak out against racial profiling. Citizens expressed their outrage through demonstrations. For instance, after the announcement that no police officers would be indicted in the 2014 case of Eric Garner, thousands of protesters marched in New York City, chanting “No justice, no peace, no racist police” and “I can’t breathe.” In South Carolina, following Walter Scott’s death at the hands of police officer, protesters gathered outside the North Charleston City Hall, carrying signs with messages such as “The whole world is watching” and “Back turned don’t shoot.”

Also in 2014, protests erupted across Saint Louis after Michael Brown’s death, setting off months of on-and-off unrest that ranged from peaceful demonstrations to riots, looting, and vandalism. Police responded by using tear gas and smoke against crowds. Unrest spiked again when a grand jury chose not to indict Officer Darren Wilson, the man who had shot Brown. Brown’s family asked for calm, saying, “We are profoundly disappointed that the killer of our child will not face the consequence of his actions. While we understand that many others share our pain, we ask that you channel your frustration in ways that will make a positive change. We need to work together to fix the system that allowed this to happen.”

Similarly, in the wake of Freddie Gray’s 2015 death in Baltimore, demonstrators marched through the streets, protesters clashed with riot police, and buildings and vehicles were damaged. Marilyn Mosby, the state’s attorney for Baltimore, addressed the turmoil that had rocked Baltimore and called on protesters to act peacefully, saying, “I will seek justice on your behalf. This is a moment. This is your moment. Let’s ensure that we have peaceful and productive rallies that will develop structural and systemic changes for generations to come. You’re at the forefront of this cause.”

Many observers expressed disapproval at the conduct of protesters, asking why African Americans were “destroying their own communities.” Describing the unrest in Ferguson, Chicago Tribune columnist John Kass wrote, “Buildings burned . . . and others were broken into and robbed. Shops were looted by gangs bent on mayhem, the crowds running into the stores, some of the shops with signs that told the looters these were black-owned businesses. But that didn’t stop those who came to take, and you could see them running out again with goods in their arms, giggling and shrieking as they celebrated their wild spree.”

Others insisted that most protesters were peaceful and that the actions of a few should not distract Americans from the larger issues. “It seems far easier to focus on the few looters who have reacted unproductively to this tragedy than to focus on the killing of Michael Brown,” noted Brittney Cooper, a professor of Africana studies at Rutgers University in New Jersey. “No, I don’t support looting. But I question a society that always sees the product of the provocation and never the provocation itself. I question a society that values property over black life.” Some noted too that stereotypes of African Americans as violent and irrational were once more at work, underpinning certain criticisms of the protests. White rioters throughout US history tend to be perceived very differently from people of color who riot. “From the Boston Tea Party to Shays’ Rebellion, riots made America, for better or worse,” points out activist Robert Stephens II. For Stephens and other protesters, the larger goal “is to transition outrage and disruption into constructive political organization.”

An NYPD officer arrests a demonstrator at a 2015 march in New York City to protest police killings of unarmed citizens.

Other observers contended that news coverage of these incidents reveals another facet of persistent, often subconscious racial bias. From local TV stations to national newspapers, media outlets have drawn criticism for presenting incidents of unrest differently depending on who is involved. According to critics, if the people in question are not white, media coverage tends to portray them as aggressive, dangerous, destructive, and criminal. By contrast, if the perpetrators are white, their actions are more likely to be presented as nonthreatening rowdiness and mischief (as were the actions among white college students in New Hampshire in October 2014). Or may describe them as courageous stands for a principle (as were the tactics of armed white demonstrators who occupied an Oregon wildlife refuge in January 2016 to protest federal government control of public land).

Similarly, some observers point out that race plays a role in what major papers, websites, and other media outlets choose not to report as news. For instance, during and after the Baltimore protests, many African Americans called for calm, worked to defuse tensions, protected property, and helped clean up the streets. These peaceful actions, however, were not covered as widely as reports on violence and destruction. Twitter users and others highlighted these disparities in coverage, using them as starting points for discussions about racial stereotypes.

Strength in Numbers

One of the largest and most vocal organizations speaking out against racism and racial profiling is Black Lives Matter (BLM). Formed in 2012 after Trayvon Martin’s death, this group has chapters all over the United States and describes its mission as “a call to action and a response to the virulent anti-Black racism that permeates our society.” Across the nation, numerous other advocacy groups for people of color have aligned themselves with the BLM movement. These groups have organized protests and demonstrations to raise awareness of racism, racial profiling, and police misconduct against people of color. For instance, groups have staged “die-ins” where protesters gather in busy public spaces—such as shopping malls, streets, and train or subway stations—and lie down on the ground or floor as though dead, a form of respect for victims of deadly profiling incidents. These dramatic demonstrations often intentionally interfere with everyday activities such as commutes and commerce as a way of drawing attention to the protesters’ cause.

Many anti-profiling demonstrations have adopted a variety of symbols and slogans that draw on past events in powerful and emotional ways. In July 2014, in response to Eric Garner’s death after a police officer used an illegal choke hold on him, Garner’s last words—“I Can’t Breathe”—became a mantra. The phrase appeared on shirts, banners, signs, and more. In December 2014, several prominent professional basketball players, including LeBron James and Kobe Bryant, attended pregame practices wearing T-shirts with the words “I Can’t Breathe.” That same month, high school basketball players at a school in California were told they wouldn’t be allowed to take part in a tournament after members of the girls’ squad wore “I Can’t Breathe” T-shirts during warm-ups.

Similarly, after the August 2014 killing of Michael Brown, the words “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” spread quickly. The eventual investigation into Brown’s killing reported that Brown probably did not say “hands up” or raise his hands in surrender before he was shot. Nevertheless, for protesters and others, the words remained symbolic of the many unarmed black men killed by officers of the law. As Hakeem Jeffries, a New York member of the US House of Representatives, put it, “‘Hands up, don’t shoot,’ is a rallying cry of people all across America who are fed up with police violence . . . in Ferguson, in Brooklyn, in Cleveland, in Oakland, in cities and counties and rural communities.”

Concerned citizens also make powerful use of social media. Posts by “Black Twitter,” an unofficial group of thousands of black Twitter users, call attention to specific incidents and foster larger conversations about racial discrimination and bias. For example, in the wake of Sandra Bland’s death, users adopted the hashtag #IfIDieInPoliceCustody, contending that police officers often lie about the circumstances of such deaths. Tweets included “#IfIDieInPoliceCustody I did not commit suicide, I did not resist arrest or be combative. I didn’t go for the taser or gun” and “#IfIDieInPoliceCustody know that they killed me. I would do everything in my power to get home to my family. So never stop questioning.” Activists and their allies use social media as a way of directly speaking to figures in power, from police chiefs to politicians. They have called for investigations into suspicious deaths and have lobbied legislators to change or introduce laws to prevent profiling.

Hoping to create change on a wider scale, reformers have carried their message to political campaigns at all levels. For instance, after seventeen-year-old Laquan McDonald died at the hands of Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke in October 2014, local civil rights advocates strongly criticized Cook County state’s attorney Anita Alvarez, who delayed pressing charges against the officers until more than a year after Laquan’s death. Citizens’ groups used social media and public demonstrations to call attention to Alvarez’s record, noting that over a seven-year period she had chosen not to file charges against police officers in more than sixty-eight cases of fatal shootings. A coalition of Chicago civil rights groups vocally opposed her candidacy in the county’s 2016 Democratic primary election for state’s attorney. Observers in the media credited these groups with Alvarez’s defeat by opponent Kim Foxx.

In Ohio, BLM and affiliated organizations achieved a similar primary victory with the defeat of Cuyahoga County prosecutor Timothy McGinty, who had controversially recommended that no charges be filed against Cleveland police officers in the November 2014 death of Tamir Rice. “These two elections show the growing influence of the Black Lives Matter movement,” stated the New York Times editorial board. “Two young people were gunned down, and the voters in those grieving communities were not going to let the prosecutors off the hook.”

At the national level, BLM activists worked to advance their agenda throughout the 2016 presidential race. Rather than endorsing a candidate, activists declared their determination to hold all candidates accountable for their policies and attitudes related to racial inequality. In addition to arranging private meetings with Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, BLM demonstrators became a vocal presence at rallies for candidates of both parties. For instance, at a 2015 town hall gathering for Sanders and rival Democratic candidate Martin O’Malley, dozens of demonstrators demanded that the candidates address concerns about racial inequality. Tia Oso of the Black Alliance for Just Immigration climbed onstage and spoke to the candidates, asking a question that encapsulated the BLM mission: “As the leader of this nation, will you advance a racial justice agenda that will dismantle—not reform, not make progress—but will begin to dismantle structural racism in the United States?” On this occasion, Sanders and O’Malley were relatively receptive to the protesters. The response at other events has ranged from combative (as when former president Bill Clinton, husband of presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, responded defensively to a BLM critic at a 2016 rally) to violent. For example, demonstrators encountered verbal and physical abuse from audience members and security staff at rallies for Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump.

Critics contend that Black Lives Matter and its allies promote irrationally destructive behavior and negative attitudes. In response to accusations that they are “too angry,” or “too aggressive,” BLM activists say that this perspective leans on racial stereotypes and that their anger is not only justified but necessary to achieve progress. “White rage doesn’t have to take to the streets and face rubber bullets to be heard,” says Carol Anderson, associate professor of African American studies at Emory University in Georgia. “Instead, white rage carries an aura of respectability and has access to the courts, police, legislatures and governors.”

Many critics of BLM also argue that the core message of Black Lives Matter is divisive and unproductive and that it inaccurately makes every incident into a conversation about race. Some suggest that a more acceptable slogan would be “All Lives Matter.” BLM activists and supporters insist that this perspective willfully ignores an uncomfortable truth about racial bias in the United States. As journalist Joshua Adams puts it, “a Black person’s life should matter as much as anyone else’s,” and yet “in this country’s past and present, Black life hasn’t been treated as if it matters.”

Individual Voices

People of all backgrounds can contribute to the conversation about racial profiling and racial inequality in the United States. A simple first step is to take an assessment known as a hidden bias test. These tests are designed to help people of all backgrounds become aware of unconscious stereotypes or prejudices that may influence their thoughts and actions. One organization that encourages the use of these tests is Teaching Tolerance, a group founded by a civil rights advocacy organization called the Southern Poverty Law Center, based in Alabama. The organization’s website explains, “Your willingness to examine your own possible biases is an important step in understanding the roots of stereotypes and prejudice in our society.” One such test was developed by Project Implicit, an organization started by psychologists at the University of Virginia, the University of Washington, and Harvard University. Project Implicit’s tests measure unconscious biases based on race, as well as on gender and sexual orientation. The educational website Understanding Prejudice offers similar tests. Similarly, you can consider if and when you might display microaggressions. Many websites, including the blog Microaggressions.com, offer examples of microaggressions and what they can mean.

Understanding your own biases can help you recognize and resist their influence on your behavior and sense of self. “The good news is, you can control it once you think about it,” says Maxine Williams, the global director of diversity at Facebook. “If, at every [move], you’re checking yourself—‘Hold on, am I objectively evaluating these people?’—you’re less likely to make those mistakes. . . . Keep yourself accountable by checking yourself, and keep others accountable.”

David O’Neal Brown, the chief of the Dallas Police Department, grew up fearing and avoiding police officers in his neighborhood. Yet he joined the police force in the 1980s, hoping to help fight the crack cocaine epidemic that had devastated many families he knew. Soon after he became police chief in 2010, his son killed a police officer in an altercation and was then fatally shot by other officers. Brown has promoted de-escalation training for police officers and emphasized the need for officers to build positive relationships with community members.

You can also speak up about the related issues, events, and causes that matter to you. One way of doing this is by sharing views on social media or through a blog. You might write a letter to the editor of a local newspaper, write articles for your school newspaper, help organize school and community events to raise awareness about certain issues, or join organizations that support related causes. Support and participate in interracial dialogue and events at your school. You can also support leaders and candidates who share your views, even if you are not yet old enough to vote.

Americans of every age, race, and ethnic background can play a role in the struggle to combat racial profiling in the United States. As more people—especially young people—become involved, many advocates for equity and justice see reason for hope. Activist and poet Jeremey Johnson says, “Voices that have gone unheard and unrecognized in previous years are now being heard and will no longer be ignored. . . . As long as there are racist systems, there will be a movement of youth visibly and vocally advocating for their civil rights. This is just the beginning.”