1

A London Boyhood

The Chaplin family lived for generations in Suffolk. The name suggests that they were descended from Huguenots, who had settled in great numbers in East Anglia from the end of the seventeenth century.1 Chaplin’s great-great-grandfather, Shadrach Chaplin, was born in 1786 and became the village boot-maker in Great Finborough, Suffolk. Shadrach inherited the taste for Old Testament names, so that the Chaplin family descent has the appearance of a biblical genealogy. Shadrach, as well as three daughters, begat Shadrach II (1814), Meshach (1817) and Abednego (1819). Shadrach II married a woman named Sophia, seven years older than himself, who came from Tunstall, Staffordshire: it became a Chaplin family tradition to give their children the middle name ‘Tunstall’, though, depending on the parish clerk, it sometimes became ‘Tunstill’.2

In 1851 Shadrach II was described as a ‘master brewer’. He lived in Carr Street, Ipswich,3 where he established an inn and eating house and conducted a pork butchery. Perhaps these enterprises did not prosper, however, for in the early 1870s he had given up the catering business altogether and taken up his father’s trade of boot- and shoe-maker. He seems still to have been in this business at the time of his death in 1892, when he bequeathed his stock-in-trade, his shoe-maker’s tools, and his estate of £144 to his widow.4 Poor Sophia had very temporary benefit from her bequest, as she died the day after her husband.

Shadrach II inevitably begot Shadrach III, but his eldest son – the great Charles Chaplin’s grandfather, born in 1834 or 1835 – had been named, for a change, Spencer. Spencer was trained in the trade of butcher. With Spencer, the first touch of poetry enters the Chaplin history, for on 30 October 1854, still a minor, he married a sixteen-year-old gypsy girl called Ellen Elizabeth Smith, in the parish of St Margaret, Ipswich.5 The witnesses to the marriage included the girl’s father, who was illiterate, but no Chaplin, so perhaps the family were not happy with the match. Ellen Elizabeth died in 1873 at thirty-five,6 and no photograph of her survives, so we can only speculate that it might have been her striking looks, jet hair and fine eyes that became the Chaplin heritage.

Eight months later, in June 1855, the couple’s first child, Spencer William Tunstill (sic), was born in Ipswich.7 Shortly after this event the young Chaplins moved to London. Spencer continued to work as a journeyman butcher, though he was later, in the 1890s, to become a publican and the landlord of the Davenport Arms, Radnor Place, Paddington. The couple were to have seven children. The fifth of these, and their third son, Charles, was born on 18 March 1863 at 22 Orcus Street, Marylebone.8 He was in time to become the father of the more famous Charles Chaplin.

Towards the end of Sir Charles Chaplin’s life, an admirer sent him an old poetry book she had found, bearing a school prize label. It had been awarded at St Mark’s Schools, Notting Hill in 1874 to Charles Chaplin in Standard 4.9 The registers of the school no longer exist, so we can discover no more details about this Charles Chaplin to confirm that he was, indeed, Chaplin’s father. However, the St Mark’s Schools in Lancaster Road were just a mile or so from the only addresses we have for Grandfather Spencer Chaplin. In 1874, Charles Chaplin Senior would have been ten or eleven, the appropriate age for Standard 4. Moreover, the registrations of births in the years 1862–4 indicate no other contender of that name for the prize in the London area. The balance of evidence seems to confirm Charles Chaplin as the diligent scholar thus rewarded.

Apart from this brief, tantalizing glimpse, there is no record of the elder Charles until the age of twenty-two, when he met and married Chaplin’s mother, Hannah Hill.10 The Hills appear to have been, if anything, more humble people than the Chaplins. Hannah’s father, Charles Frederick Hill, the son of a bricklayer, was born on 16 April 1839 – fifty years to the day before his famous grandson. There was a family tradition that he had come from Ireland, though in this respect it may be remarked that he seems to have been and remained a Protestant. His whole working life was spent as a journeyman shoe-maker: considering that a pair of disintegrating boots would come to be a symbol for Charlie Chaplin, it is curious that the making and mending of footwear should have been such a common occupation of his ancestors.

With the Hills the Chaplin story moves to South London. On 16 August 1861 Charles Hill, then living in Lambeth Walk, married Mary Ann Hodges.11 Both had been married before. There is no record of Charles Hill’s first wife, but Mary Ann’s previous marriage was to have some relevance for the early years of the younger Charles Chaplin. Socially, Mary Ann seems to have been a cut above her second husband. Her father was John Terry, a mercantile clerk. On 15 May 1854 she had married Henry Lamphee Hodges, a sign-writer and grainer.12 After four and a half years of marriage, however, poor young Hodges fell off an omnibus and suffered a fatal concussion.13

When she married Charles Hill, Mary Ann brought with her a five-year-old son by Hodges, also called Henry. Four years later a daughter was born at 11 Camden Street and christened Hannah Harriet Pedlingham Hill.14 A second daughter, Chaplin’s Aunt Kate, followed on 18 January 1870, when the Hills were living at 39 Bronti Place, Walworth.15

Charles Hill’s boot-making appears not to have given the family much stability, for they moved from lodging to lodging, always in Lambeth or Southwark, with bewildering frequency. The census of 1871 records them at 77 Beckway Street, Walworth. They are described as Charles Hill, boot-riveter, aged thirty-two; his wife, Mary Ann Hill, boot-binder, aged thirty-two; their son Henry, boot-maker, aged fifteen; and their daughters Harriet (Hannah), aged five, and Kate, aged one.16

While their step-brother, known as young Harry, stuck to the boot business, Hannah and Kate grew up into strikingly attractive women. As the music hall songs of the time delighted to relate, the streets of London were full of perils for young girls, and Hannah became pregnant. In later years she told her sons that she had run off to South Africa with a rich bookmaker called Hawkes, but it is now impossible to verify either the trip or Mr Hawkes. All that is certain is that on 16 March 1885 Hannah gave birth to a boy, who was named Sidney John. When the birth was registered and again when he was baptized at St John’s Church, Larcom Street, the father’s name was not entered. But Sidney John was not to remain fatherless for long.17

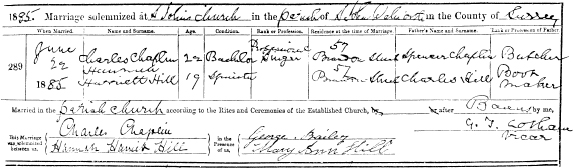

1885 – Marriage certificate of Charles Chaplin Senior and Hannah Hill.

The accouchement took place at 57 Brandon Street,18 the premises of Joseph Hodges, trading as a general dealer and most likely the brother of the unfortunate Hodges who fell off the omnibus.19 It seems probable that Hannah had left the paternal home and taken refuge with her mother’s former brother-in-law. At some point, Charles Chaplin Senior took up residence in Joseph Hodges’s house, and less than fourteen weeks after Sydney’s birth Charles Chaplin and Hannah Hill were married. Both gave their address as 57 Brandon Street. One of the two witnesses at the ceremony at St John’s Church, Larcom Street, Walworth, was Mary Ann Hill, the mother of the bride.20

Charles Chaplin described himself on the registration of the marriage as ‘professional singer’. In fact, there is no evidence that Charles had begun his career as a theatrical entertainer by the time of his marriage. His earliest appearance recorded in The Era, the weekly professional journal which provides exhaustive records of theatrical presentations, was in 1887, though The Era’s rival publication, The Entr’acte and Limelight, shows appearances by Hannah from 1884.

There is no record or family tradition to suggest what lured these two young people, with no previous connection with show business, into the theatre. Still, it was not surprising that the music halls should beckon young people with looks and even a small share of talent. This was the start of the great era of the British music hall. In London, the Alhambra (formerly the Royal Panopticon) had recently established itself as a variety house, the London Pavilion had just been handsomely reconstructed, and the palatial Empire in Leicester Square was opened in 1887. In all, London boasted thirty-six music halls of varying class in 1886, while throughout the rest of the country, from Aberdeen to Plymouth, there were no less than 234 halls with weekly bills to fill. Dublin alone had nine, Liverpool eight and Birmingham six. The opportunities were immense, and perhaps more apparent in Lambeth than in any other spot in the country. The first music hall agent, Ambrose Maynard, had set up his offices in Waterloo Road in 1858, and shortly afterwards moved to York Road, where rival firms soon sprang up. York Road ran into Westminster Bridge Road, where the Canterbury and Gatti’s Music Halls stood. Proceeding south from Westminster Bridge Road was Kennington Road, with a parade of public houses – The Three Stags, The White Horse, The Tankard and, above all, The Horns – which were favourite resorts of music-hall professionals. Large numbers of performers lived in Kennington, though the more successful preferred the somewhat smarter Brixton, immediately to the south. No doubt Charles and Hannah Chaplin were as dazzled by the glamour of the elite of the music halls at their Sunday morning get-togethers in the Kennington pubs as their son was to be fifteen years later.

Both Hannah and Charles evidently had ability. Chaplin was a shrewd judge of talent, and his descriptions of his mother’s gifts for observation and mimicry are certainly not inspired by sentiment alone. Hannah may simply have been unlucky: perhaps her particular talent was out of tune with the time. Her career was brief and not triumphant. Her recorded performances were all in small provincial music halls, and at the bottom of the bill, ‘among the wines and spirits’ as they said in a day when music halls were often also drinking places, and the artists’ names were followed on the printed programme by the tariff of refreshments. Still, Hannah’s brief time as a music hall artiste was sufficient to supply glamorous memories to stir the imagination of her adoring young sons in later years.

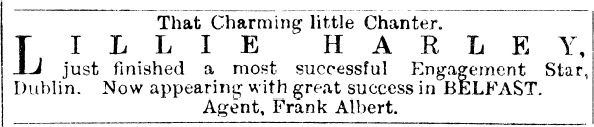

Debutants like Hannah and Charles would in those days have gained their first experience of entertaining audiences with one-night engagements in the ‘free-and-easies’ and public houses that provided entertainment for their guests. Hannah’s earliest professional engagements so far recorded are for the weeks of 24 and 31 May 1884 at the Bijou Music Hall, Blackfriars Road, which seated 150 people.21 In the week of 25 November 1884, she was appearing at the music hall at the Castle public house, Camberwell Road.22 A year later she was getting better jobs, and at the end of 1885 was singing at the Star, Dublin. By this time she had acquired an agent, Frank Albert, and by the start of the new year was sufficiently encouraged to place her ‘professional card’ in The Era. These ‘cards’ have been an almost unchanging feature of British theatrical journals for well over a century; they serve to announce a performer’s success, his availability, even his mere existence.

When Hannah placed her first card, to appear on 2 January 1886, there was apparently some doubt as to the spelling of her professional name. The announcement read:

The following week’s card read:

Next week Hannah’s stage name appeared in its definitive form:

The Refined and Talented Artist

LILY HARLEY

complimented by Proprietors, the Public and Press

Heaps of notices in different papers every week

Pleasing success SCOTIA GLASGOW

A few good songs required. Agent, F. Albert

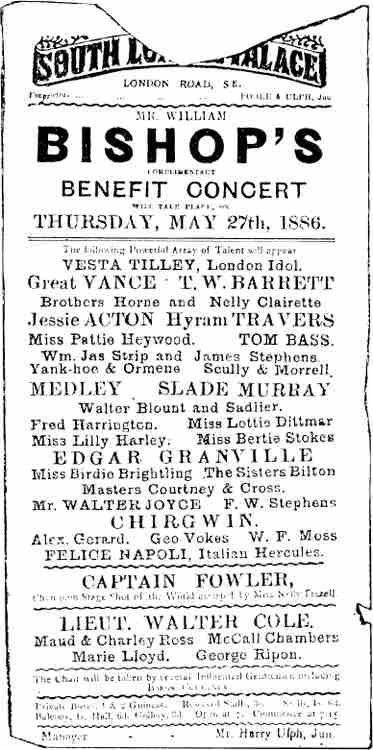

Perhaps something more than a few good songs was required, for after this Lily Harley’s ‘card’ vanished for periods of several weeks and her engagements seem to have been sporadic. On Easter Monday in April 1886, as ‘Miss Lilly Harley’, she figured modestly in a ‘Monster Company’ at the Peckham Theatre of Varieties. On 27 May 1886 she appeared (again as ‘Miss Lilly Harley’) at a benefit concert for William Bishop at the South London Palace.23 On this occasion she figured rather low on a bill whose stars were Vesta Tilley, The Great Vance and Chirgwin. Below her, however, at the very bottom of the bill, was the sixteen-year-old Marie Lloyd, destined to become the greatest star of British music hall. In the autumn there was a run of bookings (‘Lily Harley – The Essence of Refinement’) at M’Farland’s Music Hall, Aberdeen, M’Farland’s, Dundee and The Folly, Glasgow. After this, and a brief period when she inserted her ‘card’ in the Entr’acte instead of the Era (‘four or five turns every night and heaps of flowers’), both ‘cards’ and records of bookings cease altogether.24

The disappointment of Hannah’s own career must have been aggravated by watching the success of a friend, ‘Dashing Eva Lester’, with whom she shared an agent for a while. Billed as ‘The California Queen and England’s Queen of Song’, Eva had a brashness which Hannah lacked. The Era, writing of her performance at the Metropolitan in September 1886, called her ‘one of the prettiest and most fascinating serio-comic songstresses we have. In a delineation of a romp, Miss Lester, by her piquancy, won much applause …’ In his autobiography Chaplin recalls how a dozen or so years later, when they themselves had fallen upon hard times, he and Hannah found poor Eva in the street, a sick, dirty, shaven-headed derelict. The boy Charlie was horrified and ashamed to be seen with her but kindly Hannah took her in for the night and cleaned her up.

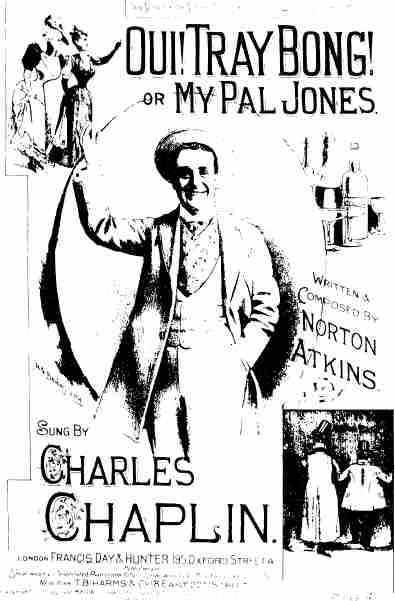

Charles Chaplin Senior’s career had a slower start but a more promising progression. His first recorded engagement was at the Folly Variety Theatre, Manchester, in the week of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, 20 June 1887. Hannah was also singing there that week – the only time the couple are known to have appeared on the same bill.25 At first he worked as a mimic, but soon developed into what was called a ‘dramatic and descriptive singer’, exerting a strong attraction upon his audiences. He was a pleasant-looking man, with no very evident facial similarity to his son. Chaplin described him as a quiet, brooding man with dark eyes, and said that Hannah thought he looked like Napoleon. The portraits that appear on the sheet music of his song successes show him with dark eyes that seem somewhat melancholy despite the broad prop grin.

1886 – Handbill for benefit concert at the South London Palace, including ‘Miss Lilly Harley’.

1893 – Illustrated song cover, with portrait of Charles Chaplin Senior.

Charles sang songs in the character of a masher, a man about town, or an ordinary husband and father, bedevilled by problems all too familiar to his audiences, such as mothers-in-law, landladies who want to be paid, nagging wives and crying babies. The clearest sign of his success is that between 1890 and 1896 the music publishers Francis, Day and Hunter issued several of his most popular songs, with his portrait prominent on the cover. This honour was accorded only to artists whose reputation the publishers were certain would sell copies. These years were the peak of Chaplin’s career. Without ever achieving the rank of contemporaries like Herbert Campbell, Dan Leno, Arthur Roberts, Charles Coborn or Charles Godfrey (to whom he was considered to have a striking physical resemblance), he was a star. As late in his career as 1898 he could share (with the ‘Beograph’ moving pictures) top billing at the New Empire Palace Theatre of Varieties, Leicester:

VERY IMPORTANT AND WELCOME RETURN OF ONE OF LEICESTER’S GREATEST FAVOURITES, MR CHARLES CHAPLIN STAR DESCRIPTIVE VOCALIST AND CHORUS COMEDIAN IN HIS LATEST SUCCESSES AND OLD FAVOURITES “DEAR OLD PALS”

All this, however, along with much unhappiness, was still to come when, on Tuesday 16 April 1889, his first son, Charles Spencer Chaplin, was born. At that moment he was playing a week’s engagement at ‘Professor’ Leotard Bosco’s Empire Palace of Varieties, Hull.26 Perhaps in later years the elder Chaplin told his son stories of the colourful Professor Bosco, because Chaplin was twice to use the name for characters in his films. Hannah had, presumably, stayed at home in London to await the birth of her baby.

Charles and Hannah were not so meticulous in registering Charles’s birth as Sydney’s; and it has tormented historians and biographers for decades that there is no official record of the birth of London’s most famous son. The fact is not especially remarkable. It was easy enough, particularly for music hall artists constantly moving (if they were lucky) from one town to another, to put off and eventually to forget this kind of formality; at that time the penalties were not strict or efficiently enforced. In the early days of his cinema fame, Chaplin said that he was born at Fontainebleau in France. This may have been one of the colourful stories with which Hannah seems to have endeavoured to brighten her sons’ lives. Later, Chaplin was certain that he was born in East Lane, Walworth,27 just around the corner from Sydney’s birthplace in Brandon Street.

It is a certain mark of a Walworth native that Chaplin refers to the street as ‘East Lane’. Until the mid-nineteenth century, that part of the thoroughfare which runs from the Old Kent Road to Flint Street was designated East Lane while the remainder, from Flint Street to Walworth Road, was East Street. Even though the whole was officially renamed East Street, the locals, like Chaplin, have ever since continued to refer to it as ‘Lane’. For Londoners, a street with a market is characteristically described as a ‘Lane’ (as with Petticoat Lane, the other side of the river). East Lane market is still as flourishing at the start of the twenty-first century as when Chaplin was a child. For some reason the East Lane traders seem to have a greater bent for drama, and the food that is cooked there has more variety and pungency, than in any other London market. Practically nothing survives from the time of Chaplin’s childhood, apart from one or two ruinous shops at the west end and The Mason’s Arms, a building whose theatrical flamboyance must have been thrilling to a small boy. Even so, the colour and vitality, the tumult of fruit and fish and pop music and old clothes still evoke an atmosphere as close, perhaps, as we may come to Chaplin’s London.

Chaplin recalled that soon after his birth the family moved to much smarter lodgings in West Square. West Square has somehow survived the destruction, by insensitive urban development, of the little streets and community life of the area. In 1890, as today, it must have been a strange oasis in a perennially depressed region: an elegant Georgian square of tall brick houses, with gardens in the centre. The move was made possible by Charles Chaplin’s growing success. In the months after his son’s birth, he was getting regular engagements, and in the year 1890–91 the music publishers Francis, Day and Hunter regarded him as such a ‘comer’ that they published no fewer than three of his songs: ‘As the Church Bells Chime’, ‘Everyday Life’ and ‘Eh, Boys?’, which was written by John P. Harrington and George Le Brunn, ‘the Gilbert and Sullivan of the halls’, who wrote most of Marie Lloyd’s greatest successes, including ‘Oh Mr Porter’. A rival publisher issued two more of his songs, ‘The Girl Was Young and Pretty’ and ‘Pals That Time Cannot Alter’.

The portrait that appears on the cover of ‘Eh, Boys?’, with the singer in a silk hat, frock coat and floppy orange bow-tie, shows a resemblance between the elder and the younger Charles Chaplin. One of the verses, illustrated by a comic vignette on the cover, ominously touches upon one of the real-life domestic troubles of the Chaplin family:

When you’re wed, and come home late-ish

Rather too late – boozy, too,

Wifey dear says, ‘Oh, you have come!’

And then turns her back on you;

Only gives you ‘noes’ and yesses’,

Until, with a sudden bound,

She quite fiercely pokes the fire up,

And then spanks the kids all round.

CHORUS

We all of us know what that means – Eh, boys? Eh, boys?

We all of us know what that means – Eh, boys? Eh?

When first she starts to drat you,

And then throws something at you,

We all of us know what that means – it’s her playful little way.

Drink was the endemic disease of the music halls. They had evolved from drinking establishments and the sale of liquor still made up an important part of the managers’ incomes. When they were not on stage the artists were expected to mingle with the audiences in the bars, to encourage conviviality and consumption – which inevitably was best achieved by example. Poor Chaplin was only one of many who succumbed to alcoholism as an occupational hazard.

In 1890, however, he was still leaping from success to success. In the summer he was invited to sign for an American tour, and in August and September was appearing in New York at the Union Square Theatre.28 The stay appears to have been pleasant and sociable. Charles’s aunt Elizabeth had married a Mr Wiggins and now lived in New York. Through her he met and made friends with Dr Charles Horatio Shepherd, who had a dentist’s practice, and Mrs Shepherd. ‘We had some delightful hours together,’ recalled Dr Shepherd, a quarter of a century later.29

J. P. Harrington, the song-writer, recalled an incident that occurred just before Chaplin’s departure for America:

One of our first clients was Charlie Chaplin, father of the famous film ‘star’. Chaplin was a good, sound performer of the Charles Godfrey type, although he, of course, lacked the latter’s wonderful talent and versatility. We wrote the majority of Charlie’s songs for some considerable time: in fact at one period, all three of the songs he was nightly singing were from our pens.

In this connection, an incident which strikes me as far more amusing now than when it happened, occurs to me. We had made an appointment with Mr David Day, head of Francis, Day and Hunter’s, the music publishers, to hear the three songs played over and sung in his office, with a view to their publication. In due course, Chaplin, Le Brunn and I arrived: the songs were played over by George and were sung by Charlie, and David was delighted with all three. The cheque book appeared on the scene. ‘Terms? The usual, I suppose?’

Trio of course, in delightful unanimity: ‘Certainly, Mr Day.’

The cheque book is opened – the pen is raised – then, George Le Brunn, anxious to paint the lily and gild refined gold, says: ‘You know, he’ll sing all these songs in America as well, Mr Day.’

Pen suspended in mid-air.

‘Ah, yes?’ murmurs Mr Day, softly. ‘And when do you go to America, Mr Chaplin?’

‘Week after next,’ says Charlie.

‘How long for?’

‘Four months.’

‘Snap!’ Cheque book returned to its little nest in the desk-drawer; pen carefully laid aside.

‘Come and see me again, when you come back from America. It won’t be any use publishing the songs while you’re singing them on the other side of the Atlantic!’

The things Charlie Chaplin and deponent said to George Le Brunn when we got outside that office would not look well if set down in this veracious narrative.30

The American trip, however, seems to have marked the final break-up of the Chaplins’ marriage.31 The 1891 census record shows Charles lodging with a music hall artist, Albert West, and his wife Anne, described as author and composer, at 38 Albert Street. Hannah and her two sons were living at 94 Barlow Street in company with Hannah’s mother, then fifty-six and euphemistically described as a wardrobe dealer. Difficulties may have arisen from Hannah’s new friendships during Charles’s absence. Certainly she had a new friend by the autumn of 1891, another music hall singer, who, over the years, frequently appeared on the same bill as Charles Chaplin.32

Leo Dryden, whose real name was George Dryden Wheeler, was born in Limehouse, London, on 6 June 1863. He had first done the rounds of the halls in 1881 but had little success for several years until one of the great stars of Victorian variety, Jenny Hill, noticed him and introduced him to her own agent, Hugh Didcott. From then onwards his career prospered. His greatest hit came early in 1891 when he introduced his sentimental ballad ‘The Miner’s Dream of Home’, depicting the nostalgia of an emigrant in the Australian gold fields. From this time on, Dryden, with his handsome square-jawed face, was established as the minstrel of England, Empire and patriotism. His later songs included ‘The Miner’s Return’, ‘India’s Reply’, ‘Bravo, Dublin Fusiliers’, ‘Freedom and Japan’, ‘The Great White Mother’, ‘The Only Way’ and ‘Love and Duty’. Unfortunately the stoic nobility of the characters he presented on stage does not seem to have distinguished his own private life. He was from all accounts erratic and given to violence. He is said to have given each of his three wives a rough time. In 1919, irked at finding his star fading, he sought publicity by singing his songs in the streets.

In October 1891 he was engaged at the Cambridge, a large music hall in Shoreditch. The popularity of ‘The Miner’s Dream of Home’ obliged the management to extend his engagement week by week until Christmas. During these twelve weeks in London Dryden brought his affair with Hannah Chaplin to fruition. We have comic evidence of his courtship. As he became more successful, Dryden took to inserting flamboyant advertising in the professional papers. A typical example reads:

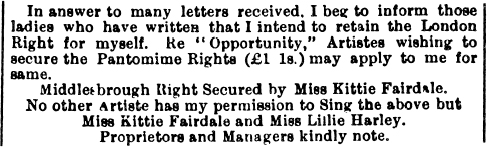

It was a feature of these advertisements that Dryden aggressively asserted his rights in his songs, offering licences for performances outside London and threatening legal proceedings against anyone who infringed his rights. Nevertheless, one exceptional announcement in November 1891 introduced, for those who could recognize it, a romantic touch:

Miss Kittie Fairdale may have paid her guinea. Miss Lily Harley – Hannah Chaplin – had presumably not; nor was she very likely to take advantage of her privilege, since she had no apparent engagements at which she could sing ‘Opportunity’. Still, the announcement must have found her vulnerable indeed. This was the first time for more than five years that her name had appeared in the professional press, and now it was linked with the star of the day. Dryden was thirty and handsome, and the flattery of his announcement must have been irresistible. Perhaps, indeed, the association with Dryden stirred Hannah to a new phase of artistic activity, with links to her younger son’s future musical abilities. On 14 June 1895 (by which time Hannah’s fortunes were at their lowest) The Era reported,

Miss Lily Harley writes us that Mr Charles Brighten is not the original author of ‘My Lady Friend’, but that she wrote a song with this title three years ago, and that the song was sung successfully by Miss Kittie Fairdale at the Royal, Holborn.

Dryden’s Encore advertisement appeared on Friday, 28 November 1891. Nine months and three days later, on 31 August 1892, Hannah gave birth to Leo Dryden’s son, also George Dryden Wheeler.

Thus the young Charles Chaplin found himself fatherless, but with another half-brother. He was three and a half; Sydney was four years older. In his autobiography he recalls that at this time the children and their mother were still living in some affluence. He attributed the cause to his mother’s work on the stage and recalled that she would tuck the two boys in bed and leave them in the care of a housemaid while she went to the theatre. Since there is no record of Hannah working at this period, and since Charles’s payments for the support of his sons seem to have stopped quite early, it can only be supposed that Leo Dryden was providing this temporary prosperity. What the domestic arrangements of Leo and Hannah were is not clear. Years later their son – he had adopted the professional name of Wheeler Dryden – said that according to information he had received from his father, they lived ‘for a year or two as man and wife’33 but neither Chaplin nor Sydney recorded any first-hand recollection of Leo Dryden.34

The comfort which sheltered Chaplin’s first three or four years was soon to end. Hannah’s liaison with Leo did not long survive the birth of their child. Hannah seems to have been a devoted, affectionate and protective mother, and to have loved the new baby as fiercely as she did her older sons. It is easy then to appreciate the shock that she must have suffered in the spring of 1893 when the appalling Dryden entered her lodgings and snatched away their six-month-old son. The baby was to vanish from the lives of the Chaplins for almost thirty years.

Poor Hannah had only wanted to be Lily Harley and to dream of the glamour of the stage. Now her life became a nightmare. Other troubles descended from the very moment that her baby was stolen from her. Her mother, Chaplin’s Grandma Hill, had apparently left Grandfather Hill: family tradition said that her husband had caught her in a compromising situation with another man. Since the separation, Grandma Hill had gone from bad to worse. She had taken to drinking heavily, and supported herself by hawking old clothes. She became more and more eccentric and, in the village-like community of Lambeth and Southwark, must have been a grave embarrassment to her family. Eventually, in February 1893, she was taken off the streets into the Newington Workhouse, and from there transferred to the Infirmary.

The doctors recorded: ‘She is incoherent. She says that she sees beetles, rats, mice and other things about the place. She thinks that the doctors at the Infy. tried to poison her. She makes a lot of rambling statements and frequently contradicts herself.’35 After some days she became ‘much more noisy and troublesome’, and on 23 February she was certified insane and committed to the London County Asylum at Banstead.36 Dr Williams, who signed the certificate, found her still imagining rats, mice and beetles in her bed. He noted that her condition had been deteriorating for several months and attributed her madness to drink and worry. Cheap gin was a perilous solace. Mary Ann was now fifty-four years old. Her husband was ordered to pay four shillings a week towards her support.

The collapse of her mother must have been appalling for Hannah, even if she had no foreboding of her own eventual fate. Yet she appears to have kept the catastrophe from her boys, hard as that must have been in the gossipy intimacy of the Lambeth streets. Chaplin only remembered his grandmother as ‘a bright little old lady who always greeted me effusively with baby talk’. Mary Ann survived in Banstead Asylum for two more years.

Hannah now found herself without any livelihood. Leo had gone out of her life and Charles appears to have contributed little or nothing to the support of his sons. Chaplin remembered that she earned a little money by nursing and by dress-making for fellow members of the congregation of Christ Church, Westminster Bridge Road: she had turned to religion in search of some kind of spiritual comfort. She seems also to have tried to take up her stage career again. As autobiographer, Chaplin generally proves phenomenally accurate in reporting those events in which he was personally involved, so there is little reason to question his version of his own first appearance on the stage in about 1894. Hannah had succeeded in getting an engagement at the Canteen, Aldershot. Her health had already begun to deteriorate and during the performance her voice failed her. The Aldershot audience – mostly soldiers – was notoriously rough and became hostile. When Hannah left the stage, the manager, who had seen little Charlie do turns to amuse Hannah’s friends backstage, led him on as an extempore replacement. Unabashed, the child obliged with a song, ‘’E Dunno Where ’E Are’, which the coster comedian Gus Elen had made a hit in 1893, and which described the dismay of his former pals at the airs put on by a coster who had come into an inheritance:

Since Jack Jones come into a little bit of splosh,

Why ’E dunno where ’E are!

The performance was a great success and to Charlie’s delight the audience threw money on to the stage. His business sense was born that night: he announced that he would resume the performance when he had retrieved the coins. This produced still greater appreciation and more money, and Chaplin continued to sing, dance and do impersonations until his mother carried him off into the wings. He noted in his autobiography that this night marked his first appearance on the stage and his mother’s last, but this is not quite accurate (unless he misjudged his own age at the time) since in his later book My Life in Pictures he illustrates a handbill advertising a one-night appearance of ‘Miss Lily Chaplin, Serio and Dancer’ at the Hatcham Liberal Club on 8 February 1896.

Hannah’s financial situation must have been desperate, but her sons were to remember more vividly than the privations her efforts to bring gaiety and small pleasures into their lives: the weekly comic, bloater breakfasts and an unforgettable day at Southend after Sydney had providentially found a purse containing seven guineas but no means of identifying its owner. She was, when well, a constantly amusing companion. She would sing and dance her old music hall numbers and act out plays for them. In his old age Chaplin still recalled the emotion aroused in him by her account of the Crucifixion and of Christ as the fount of love, pity and humanity.

The music halls may not have appreciated her gifts, but she had the greatest of audiences in her young sons. She undoubtedly had a talent, and – consciously or not – she applied herself to cultivating the innate gifts of observation that both children seemed to share. Chaplin recalled in 1918:

If it had not been for my mother I doubt if I could have made a success of pantomime. She was one of the greatest pantomime artists I have ever seen. She would sit for hours at a window, looking down at the people on the street and illustrating with her hands, eyes and facial expression just what was going on below. All the time, she would deliver a running fire of comment. And it was through watching and listening to her that I learned not only how to express my emotions with my hands and face, but also how to observe and study people.

She was almost uncanny in her observations. For instance, she would see Bill Smith coming down the street in the morning, and I would hear her say: ‘There comes Bill Smith. He’s dragging his feet and his shoes are polished. He looks mad, and I’ll wager he’s had a fight with his wife, and come off without his breakfast. Sure enough! There he goes into the bake shop for a bun and coffee!’

And inevitably during the day, I would hear that Bill Smith had had a fight with his wife.37

He paid touching tribute to his mother in an earlier press statement, an ‘autobiography’ published by Photoplay in 1915:

It seems to me that my mother was the most splendid woman I ever knew … I have met a lot of people knocking around the world since, but I have never met a more thoroughly refined woman than my mother. If I have amounted to anything, it will be due to her.

Soon after Charlie’s sixth birthday, the family’s situation reached a new crisis. Hannah became ill – it is not certain with what, but Chaplin recalls that she suffered from acute headaches. On 29 June 1895 she was admitted to the Lambeth Infirmary, where she stayed until the end of July. On 1 July Sydney was taken into Lambeth Workhouse,38 and four days later placed in the West Norwood Schools, which accommodated the infant poor of Lambeth. As Poor Law institutions went, Norwood was pleasant enough. It stood on the slope of a hill facing green fields, on the boundary of Croydon and Streatham, which were then still quite rural. The building, in which Sydney shared a dormitory with thirty-five other boys aged between nine and sixteen, had been erected only ten years before. There was a steam-heated swimming bath, and the children were not uniformed. Under each bed was a wicker basket for the children to store their clothes at night. Each child had his own towel, brush and comb, but at an inspection a year or two after Sydney’s stay there, it was noted that ‘only a few of them are provided with tooth-brushes’. Sydney remained at Norwood until 17 September; he was lucky not to stay longer than the autumn, as the inspectors were gravely concerned about the inadequate heating arrangements in the Schools. Strangely, when Sydney was discharged, he was given into the care of his step-father, so perhaps Hannah was still not well enough to care for the boys.39

In Charlie’s case, the Hodges – Grandma Hill’s relations by her first marriage – came to the rescue and Charlie was lodged at 164 York Road, with John George Hodges, son of the Joseph Hodges from whose house Charles and Hannah had married, and nephew of the unfortunate Henry Lamphee Hodges who fell from the omnibus. He had, as it happened, taken up the same profession as his deceased uncle, and was a master sign-writer. John George entered Charlie into Addington Road Schools, along with his own son, who was a year or so younger. Charlie appears to have stayed in the school only a week or two: he was never to undergo any prolonged period of day-school attendance.40

Only eight months after Sydney’s discharge from Norwood Schools, both Chaplin boys were to experience in earnest life in charity institutions. Hannah was again taken into the Infirmary, and Sydney and Charlie, now eleven and seven, were admitted to the workhouse, ‘owing to the absence of their father and the destitution and illness of their mother’.41 Charles Chaplin Senior was traced and reluctantly appeared before the District Relief Committee. Somewhat heartlessly, he told them that while he was willing to take Charlie, he would not accept responsibility for Sydney, who was born illegitimate. The Committee retorted that since Chaplin had married the boy’s mother, he was now legally liable for Sydney’s maintenance. At this stage, however, Hannah intervened to reject the idea of the boys living with their father as wholly repugnant, since he was living with another woman. Charles was not slow to point out her own adultery. No doubt somewhat bewildered by the family bickering, the Relief Committee decided that it was desirable to keep the boys together and that the best solution would be to place them in the Central London District Poor Law School at Hanwell. It was ruled that Chaplin should pay the sum of fifteen shillings a week towards the cost of keeping them: ‘The man is a Music Hall singer, ablebodied and is in a position to earn sufficient to maintain his children.’ On 1 July, a fortnight after the boys had been transferred to Hanwell, the Board of Guardians reported to the Local Government Board that Chaplin had consented to this arrangement. However, it was one thing to get Chaplin to consent, quite another to get him to pay. Throughout the following year the Board of Guardians was receiving regular reports of Chaplin’s non-payment.

The boys knew nothing of this, of course. On 18 June 1896 they were driven the twelve miles to Hanwell in a horse-drawn bakery van, and Chaplin always recalled with a pleasant nostalgia the adventurous drive through the then beautiful countryside. He thought Hanwell less sombre than Norwood, though it was not so up-to-date. Part of the buildings had been adapted from a much older institution, others were one-storeyed corrugated iron structures; but it had a swimming pool and large play areas, and the heating arrangements were at least efficient. In one respect Sydney and Charles were fortunate. Only six or seven years earlier massive reform and reorganization had taken place at Hanwell. Before that it had been notorious as a forcing ground for the contagion of ophthalmia: many children who had entered the school healthy left it either wholly or partially blind from the disease.

By 1896 modern treatments and the isolation of sick children had checked the spread of the most infectious diseases. It was harder to control vermin, and Charlie had the misfortune to be one of the thirty-five children who picked up ringworm in the course of the year. He retained bitter memories of having his head shaved, iodined and wrapped in a bandanna. Aware of the contempt of the other boys for the ringworm sufferers, he carefully avoided being seen by refraining from looking out of the window of the first-floor ward where those so affected were confined.

Life at the school was generally healthy, with games and exercises, country walks and an emphasis on hygiene. The administration was by and large humane and the food sufficient. (Charlie recalled that Sydney worked in the kitchen and was able to smuggle out rolls and butter, but that for all his pleasure in the thrill of stolen fruits he had no actual need for extra nutrition.) The boys remembered with a thrill of horror the weekly punishments by cane or birch administered to infant malefactors by ‘Captain’ Hindom, the school drill master.42 Once Charlie found himself, quite unjustly, included in the punishment list: he had been innocently using the lavatory at the moment it was discovered that some paper had been set on fire there, and received three strokes of the cane from Hindom as the presumed arsonist.

The worst part of institutional life was separation from Sydney. The adversities of their childhood had created an unusually close bond of understanding between them, which was to survive throughout their lives. Not long before her death in 1916, their Aunt Kate Mowbray wrote:

It seems strange to me that anyone can write about Charlie Chaplin without mentioning his brother Sydney. They have been inseparable all their lives, except when fate intervened at intervals. Syd, of quiet manner, clever brain and steady nerve, has been father and mother to Charlie. Charlies always looked up to Syd, and Sydney would suffer anything to spare Charlie.43

For his own part, Sydney wrote to his brother, almost forty years after their Hanwell days: ‘It has always been my unfortunate predicament or should I say fortunate predicament? to concern myself with your protection. This is the result of my fraternal or rather paternal instinct …’44

Charlie was very soon to be deprived, at least temporarily, of this protection. In November 1896 Sydney was transferred to the training ship Exmouth, moored at Grays in Essex. The Exmouth was an old wooden-walled, line-of-battle ship which had seen service at Balaclava, and since 1876 had been used by the Metropolitan Asylums Board ‘for training for sea-service poor boys chargeable to metropolitan parishes and unions’.45 The children came from all parts of London, and the Board were selective about entrants. There was, indeed, some difficulty in maintaining the full complement of 600 boys since there was ‘not unnaturally, a disinclination on the part of the various school authorities to part with all their finest “show” boys’.46 Boys became eligible at the age of twelve, and Sydney’s selection was a tribute to his physique, intelligence and athletic prowess. Life on the Exmouth was tough but varied. The boys’ first task ‘is to learn how to mend and patch their clothes, and thus acquire the deftness of using their fingers, which every real sailor displays. They also learn to wash their own clothes and to keep their lockers (one of which is set apart for each lad) and their contents in good order and condition. Each boy has his own hammock, which is neatly stowed away during the day, leaving the decks free from all encumbrance, in the shape of bedding.’47 The general schooling was good, and the boys learned seamanship, gunnery and first aid. Sydney was to turn to his subsequent advantage the emphasis in the Exmouth’s curriculum on gymnastics and band training. He learned to be a bugler. Sydney left the Exmouth with generous enough memories of the ship and its veteran captain-superintendent, Staff-Commander W. S. Bourchier. Years afterwards, he took the trouble to arrange and finance special treats and entertainments for later generations of youthful crewmen.

The two boys stayed in their respective institutions throughout 1897. There is little trace of how or where Hannah lived during this period, though at one point she was resident at 133 Stockwell Park Road. Meanwhile, the Southwark Board of Guardians wrestled with the problem of extracting from Charles Chaplin Senior the weekly contribution of 15s he had agreed to pay towards the maintenance of his sons. The first problem was to find him, though had the guardians been more assiduous readers of the music hall professional press they would have been aware that he was still in work around the provinces and occasionally in London.48

Early in 1897 Dr Shepherd, the New York dentist with whom Charles had become friendly on his 1890 American tour, visited London and recalled that he was given ‘a very, very Royal time’ during his three months’ stay, not only by Charles but also by Charles’s brother Spencer and their father, also Spencer. When Dr Shepherd left London, they presented him with several pieces of Doulton ware, which was produced locally and for those days was comparatively costly. Charles was clearly not in want of money during this period.49

Very soon after Dr Shepherd’s visit Charles’s father died. His will, drawn up one week before his death on 29 May 1897, contained a curious provision, requiring ‘that my son, Charles Chaplin, doth carry on the business of The Davenport Arms, Radnor Place, Paddington for a period of 12 months, during which time he is to find a home for Mrs Machell. At the expiration of 12 months, the business is to be sold and the proceeds equally divided amongst my children unless an amicable arrangement can be made amongst themselves.’50 Grandfather Chaplin’s intention may have been to try to introduce some stability into the life of his undeniably feckless son. If that was the intention, however, it was frustrated, for Charles managed, through some technical flaw in the will, to evade responsibility for the paternal pub and the mysterious Mrs Machell.

The Southwark Board of Guardians, on the other hand, was not about to permit him to shuffle off his family responsibilities. After more than a year during which he had not paid one penny of the agreed contribution,51 the Guardians applied for a warrant for Chaplin, for neglecting to maintain his children, and offered a reward of £1 for information leading to his arrest. Happily there seemed to be the same kind of fraternal bond between Charles Chaplin Senior and his brother Spencer, eight years his senior, as there was between his two sons. Spencer stepped in with the back payments – amounting to the very considerable sum of £44 7s – and averted Charles’s arrest. The Guardians had clearly had enough of Chaplin and at their meeting on 11 November 1897 it was moved that the two boys should be returned to their father within fourteen days. Again the problem was to find him. On 16 November the Clerk to the Guardians wrote to the long-suffering Spencer:

1896 – Extracts from minutes of Southwark Board of Guardians.

Dear Sir,

I shall esteem it a favour if you will kindly inform your brother Charles Chaplin that the Guardians desire him to relieve them of the future maintenance of his two children Sydney and Charles within 14 days from this date: I am compelled to write to you not knowing his address.52

Evidently Spencer was unable or unwilling on this occasion to help, and again, two days before Christmas, the Guardians applied for a warrant for Charles’s arrest. A helpful citizen named Charles Creasy supplemented his Christmas budget by informing on poor Charles, and claimed the £1 reward. Chaplin was arrested early in January in Leicester, where he was sharing the top of the bill at the New Empire Theatre of Varieties with the ‘Beograph’ moving pictures.53 This time he swiftly paid up the outstanding £5 6s 3d, but passed on future responsibility to Hannah, by requesting that the boys should be discharged to the care of his wife. So, on 18 January 1898, Charlie came home again. He had been an inmate of Hanwell Schools for exactly eighteen months. Sydney’s return from the Exmouth two days later completed the family reunion.

Charlie later remembered that they moved from one back room to another: ‘It was like a game of draughts: the last move was back to the workhouse.’ In the early summer they were living in a room at 10 Farmers Road, a little row of cottages directly behind Kennington Park. It was from here that on 22 July 1898 the three of them trundled three-quarters of a mile up Kennington Park Road to the Lambeth Workhouse in Renfrew Road, to throw themselves once more on the mercy of the parish authorities. They stayed ten days in the workhouse, then Sydney and Charles – now thirteen and nine respectively – were sent off to Norwood Schools. This time they stayed only a fortnight, as Hannah announced her intention of taking herself and the boys away from the workhouse. Sydney and Charles were duly brought back from Norwood and on Friday, 12 August the three of them were discharged.54 However, it was only a ruse of Hannah’s to see her sons again. Charles vividly remembered that day, and the joy of meeting his mother at the workhouse gates in the early morning. Their own clothes had been returned to them, rumpled and unpressed after obligatory steam-disinfection by the workhouse authorities. With nowhere else to go they spent the day in Kennington Park, a rather cheerless patch of green, though it had recently been glorified with a fountain by Doultons’ popular sculptor-ceramist George Tinworth.

The resourceful Sydney had saved nine pence, which they spent on half a pound of black cherries to eat in the park, and a lunch of two halfpenny cups of tea, a teacake and a bloater which they shared between them. They played catch with a ball which Sydney improvised out of newspaper and string, and after lunch Hannah sat crocheting in the sun while her children played. Finally she announced that they would be just in time for tea in the workhouse, and they set off again up Kennington Park Road. The workhouse authorities, Charles recalled, were very indignant when Hannah demanded their readmission, since it involved not only paperwork but also a fresh disinfection of their clothes. An added bonus of the day out was that Sydney and Charles had to remain in the workhouse over the weekend and so spend more time with their mother. On Monday they were sent back to the Norwood Schools.

This adventure which Hannah had devised for them remained a joyous memory for her sons to the end of their lives.55 Ironically, the courage to carry it out was probably a sign of her growing mental instability. On 6 September – just three weeks after the outing to Kennington Park – she was taken from the workhouse to the Infirmary. The intervening period in the workhouse had left her in poor physical condition: she had dermatitis and her body was covered in bruises. No one troubled or dared to inquire into the cause of her injuries; they were most likely explained by violent encounters with other patients as a result of her mental condition. The doctor scribbled the abbreviation ‘Syp.’ in the corner of the form recording her physical condition on admission, suggesting that he may have supposed tertiary syphilis as the cause of her disorder. There is no other evidence to support this, though Chaplin to the end of his life appears to have been fascinated and frightened by this venereal disease. Hannah was committed to Cane Hill Asylum, the doctors reporting:

Has been very strange in manner – at one time abusive & noisy, at another using endearing terms. Has been confined in P[added] R[oom] repeatedly on a/c of sudden violence – threw a mug at another patient. Shouting, singing and talking incoherently. Complains of her head and depressed and crying this morning – dazed and unable to give any reliable information. Asks if she is dying. States she belongs to Christ Church (Congregation) which is Ch. of E. She was sent here on a mission here by the Lord. Says she wants to get out of the world.56

On her admission to the hospital Hannah had given her occupation as ‘machinist’ – so she was still apparently supporting the family by sewing whilst in Farmers Road – and gave her first name as ‘Lily’. The workhouse authorities corrected it to Hannah Harriett. As a true theatrical, she had had the presence of mind to tell them that she was twenty-eight: her real age at that time was just over thirty-three.

After Hannah and her children re-entered the workhouse in July, the Board of Guardians resumed their pursuit of Charles Chaplin Senior. He was now living at 289 Kennington Road,57 a few minutes away from Spencer’s pub, the Queen’s Head, on the corner of Broad Street and Vauxhall Walk. A fortnight after Hannah was committed to the asylum, Sydney and Charles were discharged from Norwood Schools to the care of their father.

When they were delivered – again in a bakery van – to his house, Charles remembered seeing his father only twice before. Once, he said, was on stage at the Canterbury Music Hall in Westminster Bridge Road; another time Charles had actually addressed him when they had met outside the house in Kennington Road. On that occasion Charles Chaplin Senior was accompanied by the woman with whom he was still living, and who is identified in Chaplin’s autobiography only as ‘Louise’. Number 289 Kennington Road was (and remains) a large, handsome, late Georgian terraced house, set back behind a small front garden. Charles Senior occupied the two first-floor rooms with Louise and their four-year-old son (another half-brother for Charlie). The arrival of the two boys cannot have been convenient. In fact Sydney and Charles lived with their father for no more than two months, but it clearly seemed like years to them. Louise was surly and resentful and took a particular dislike to Sydney (who on one occasion took his revenge by threatening her with a sharpened button-hook). When she drank she became more morose. Yet in retrospect Chaplin felt a kind of sympathy for her. She had once been a beauty and had sad, doe-like eyes; Chaplin sensed that she and his father were genuinely in love. Life with the elder Chaplin could not have been easy. He was drinking heavily by this time and rarely came home sober. There were moments when he was attentive and charming and full of amusing stories about the music halls, but more often Charlie remembered the fights between his father and Louise, and the occasions when he himself was locked out of the house. One of these occasions led to a visit by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Hannah, meanwhile, had periods of remission from her illness. On 12 November 1898 she was discharged from Cane Hill Asylum,58 and soon afterwards gathered up her sons from 289 Kennington Road. The three of them moved into a room at 39 Methley Street, behind Haywards’ pickle factory, which exuded a pungent atmosphere throughout the neighbourhood. Their home was next to a slaughterhouse; Chaplin remembered the horror with which he realized that a merry slapstick chase after a runaway sheep was destined to end in tragedy and the slaughter of the entertaining animal.

Apart from this, life in Methley Street appears not to have been too uncomfortable. Charles Chaplin Senior was making occasional contributions to his sons’ support, presumably to ensure that they did not return to disrupt the dubious harmony of Kennington Road. Hannah had returned to church and sewing, putting together blouses that were already cut out, for a sweatshop which paid her 1½d apiece – a memory which perhaps inspired Chaplin’s description of the heroine’s mother in early versions of the script for Limelight, as a worn but still beautiful woman, bent over a sewing machine in an attic room. About this time Sydney took a job as a telegraph boy at the Strand Post Office. Louise, at the insistence of the Board of Guardians, had sent Charlie back to the Kennington Road Schools. He did not enjoy it very much, and to the end of his life complained of the failure of so many teachers to stir the imagination and curiosity of their pupils. He spent his last day at Kennington Road Schools on Friday 25 November 1898.59

Charlie Chaplin was now to become a professional entertainer. In early interviews he occasionally gave rather romantic accounts of his discovery by William Jackson, the founder of the Eight Lancashire Lads:

One day I was giving an exhibition of the ordinary street Arab’s contortions, the kind so common in the London streets, when I saw a man watching me intently. ‘That boy is a born actor!’ I heard him say, and then to me, ‘Would you like to be an actor?’ I scarcely knew what an actor was in those days, though my mother and father had both been connected with the music hall stage for years, but anything that promised work and the rewards of work as a means of getting out of the dull rut in which I found myself was welcome, and I listened to the tempter with the result that a few days later I was making my appearances in London suburban music halls with the variety artists known as the Eight Lancashire Lads.60

This was the kind of story newspaper reporters and readers loved in the 1920s. In his autobiography Chaplin explained, more mundanely but more credibly, that his father knew Mr Jackson and persuaded him to take on his son. Hannah was convinced: the arrangement was that Charlie would get board and lodging on tour and Hannah would receive half a crown a week. William Jackson and his wife were evidently reliable people to whom she could entrust her son. They were devout Catholics; they allowed their own children to perform in the troupe; and they proved conscientious about enrolling the Lads in schools in the towns where they appeared – though Charlie was only too well aware that these weekly attendances did not greatly benefit his education. Mr Jackson’s least appealing habit was to pinch the boys’ cheeks if they looked pale before they went on: he liked to boast that they did not need make-up since they had naturally rosy cheeks. A writer in a music hall paper, The Magnet,61 described the act at the time that Charlie was a part of it:

A bright and breezy turn, with a dash of true ‘salt’ in it, is contributed to the Variety stage by that excellent troupe, the Eight Lancashire Lads whose speciality act we cannot speak too highly of. Mr William Jackson presents to the public eight perfectly drilled lads, who treat the audience to some of the finest clog dancing it is possible to imagine. The turn is a good one, because it gets away from the usual, and plunges boldly into the sea of novelty. The Lancashire Lads are fine specimens of boys and most picturesque do they look in their charming continental costumes: indeed, they are useful as well as ornamental, and treat us to a most enjoyable ten minutes’ entertainment. The head of the troupe is William Jackson, and with this gentleman I had an interview recently. Mr Jackson some years ago commenced his career in Liverpool where he acquired a thorough knowledge of dancing. I was advised, he said to me, to go in for it professionally, so I gave up my work as a sculptor, and devoted myself to the stage. [Chaplin understood that Jackson had originally been a school teacher.]

Mr Jackson told the interviewer that the Lads

made their first appearance at Blackpool, achieving a big success there, and afterwards going to the chief halls in the provinces. You see, the turn was quite new and caught on at once … and we are always endeavouring to improve the show. After this we were engaged for pantomime at the Newcastle Grand, and scored again in a most satisfactory way … After the run of this engagement I brought the lads to London, and they made their appearance at Gatti’s [Westminster Bridge Road]; this being followed by other halls and also the Moss and Thornton tour.

Asked if any of his own sons appeared in the act he replied, ‘Yes, two of them are included in it; and the other six are pupils. They have all been trained under my personal supervision, and in this direction my wife gives me much assistance.’ Again Chaplin’s recollection was slightly different: he believed that four of the Lads were Jackson offspring, though one of these was a girl with her hair cut like a boy’s. In any event, the Magnet correspondent concluded,

Jackson’s Eight Lancashire Lads are all charming little fellows, well cared for, and an inspection of them was sufficient to satisfy me that they are all endowed with that which is most delightful to youth – good health and spirits. They take as much interest in their work as does [sic] Mr and Mrs Jackson themselves; and the public need never fear of having their interests neglected by the eight boys from Lancashire.

Charlie remembered that he had to rehearse his clog dancing for six weeks before he was allowed to appear – almost paralysed with stage fright. His debut may then have been at the Theatre Royal, Manchester, where the troupe appeared in the Christmas pantomime Babes in the Wood, which opened on Christmas Eve. If so, Charles Chaplin Senior would have been on hand to watch his son’s first steps: he opened on Boxing Day at the Manchester Tivoli. Certainly, Charlie was working with the troupe by 9 January 1899, when he was enrolled by Mrs Jackson at the Armitage Street School, Ardwick, Manchester.62

William Jackson’s youngest son, Alfred, a year older than Charlie, remembered the new boy, not quite ten, being taken on:

He was living with an aunt and his brother Sydney above a barber’s shop [now a draper’s] in Chester Street, off the Kennington-road. He was a very quiet boy at first, and, considering that he didn’t come from Lancashire, he wasn’t a bad dancer. My first job was to take him to have his hair, which was hanging in matted curls about his shoulders, cut to a reasonable length.

He came to stay with us at 167 Kennington-road, and slept with me in the attic under the tiles. While we were in London we all went to the Sancroft-street Schools [opposite Kennington Cross], and he began to brighten up as he got to know us better. He was a great mimic, but his heart was set on tragedy. For weeks he would imitate Bransby Williams in ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ wearing an old grey wig and tottering with a stick, until we others were sick of him.63

Charlie himself had vivid memories of his Bransby Williams impersonation. Mr Jackson had seen him entertaining the other boys with imitations of Williams in his ‘Death of Little Nell’, from The Old Curiosity Shop, and had decided it should go into the act, but it was disastrous. Charlie wore his regular Lancashire Lads costume of blouse, knickerbockers, lace collar and red dancing shoes, with an ill-fitting old man’s wig, and his inaudible stage whisper irritated the audience into stamping and cat-calls. The solo experiment was not repeated.

Charlie had, in fact, a number of opportunities to study Bransby Williams. The Eight Lancashire Lads got engagements at the major London and provincial halls and shared the bill with Williams and other top artists of the time. Chaplin clearly remembered seeing Marie Lloyd and remarking how seriously she approached her work, but thought he had not seen Dan Leno, who was on the same bill at the Tivoli in April 1900, in his prime.

Chaplin made the acquaintance of the English music halls at their zenith. In the years since his father’s debut, new civic organization and safety regulations had closed many of the innumerable tiny fleapit theatres, and in every urban centre opulent new Empires and Palaces had sprung up. These grander theatres, and a conscious move towards respectability by the highly organized new managements, had begun to attract a more discerning middle-class audience. The huge salaries that star artists could earn attracted a lot of talented people from the legitimate theatre, Bransby Williams and Albert Chevalier among them. In 1897 Charles Douglas Stuart and A. J. Park, the first historians of the music halls, could write:

The position occupied by the variety stage today is as conspicuous everywhere as it is unique. Neither drama nor opera has had erected to its service more numerous or more palatial temples, and neither branches of art can count so many professors and supporters as those devoted to the cause of this peculiar and popular form of entertainment. But if the music hall has a glowing and interesting past, it has a still more golden and attractive future.

Keeping, as before, in close and sympathetic touch with the great beating heart of the people and enlisting in its service, as its sphere of usefulness extends and broadens, the active and artistic co-operation of the best authors, the best artistes and the keenest intelligence of its day, it will necessarily yield still better and brighter results, and the cultured audience of the twentieth century – when, melancholy prospect! the present writers have been gathered to their fathers – may sit through a programme in which Shakespeare and the Henry Irvings of the future may collaborate to glorify and adorn.64

Even to a ten-year-old in a troupe of clog dancers, the music halls of those times must have provided an incomparable schooling in method, technique and discipline. A music hall act had to seize and hold its audience and make its mark within a very limited time – between six and sixteen minutes. The audience was not indulgent, and the competition was relentless. The performer in the music hall could not rely on a sympathetic context or build-up: Sarah Bernhardt might find herself following Lockhart’s Elephants on the bill. So every performer had to learn the secrets of attack and structure, the need to give the act a crescendo – a beginning, a middle and a smashing exit – to grab the applause. He or she had to learn to command every sort of audience, from a lethargic Monday first-house to the Saturday rowdies.

The best of music hall was invariably rooted in character. There were the eccentrics, such as Nellie Wallace or W. C. Fields (who, as a tramp juggler, was popular on both sides of the Atlantic), who always presented the same well-loved character; or there were the performers like Marie Lloyd, Albert Chevalier, George Robey or Charles Chaplin Senior himself, who would create an entire and individual character within each song. Hetty King, who was beginning her career at this time, was to bill her act as ‘Song Characters True to Life’. The ‘true to life’ was important. The audience was keenly alive to falsehood, and comedy had to observe its own laws of dramatic and psychological truth.

Charlie seems to have toured with the Eight Lancashire Lads throughout 1899 and 1900. The registers of St Mary the Less School, Lambeth, reveal that Mrs Jackson enrolled him there during the Lads’ engagement at the Tivoli. He was evidently still with them at the end of the year, when the pantomime season came round. Alfred Jackson remembered, ‘Charlie accompanied us on tour and played in the first Cinderella pantomime at the [London] Hippodrome as one of the cats. Finally he left the Lancashire Lads for the “legitimate”.’65 This confirms Chaplin’s own very circumstantial memories of Cinderella, although William Jackson’s boys do not appear on the programme. Such a popular act might be expected to receive advertisement, but it is not entirely surprising that it did not on this occasion. The cast of a spectacular pantomime presentation at this time could be huge, with scores of extras and speciality acts. Mr Jackson, too, may have felt that work as pantomime animals, though profitable, was slightly demeaning. The cast list ends: ‘Members of the Prince’s Hunting Party, Guests at the Bar, Foreign Ambassadors and their Retinue etc. etc.’ Charlie and the Lads may have been the etceteras.

Opening in January 1900, the Hippodrome was London’s latest theatrical marvel. The impresario Sir Edward Moss had set out to give Londoners ‘a circus show second to none in the world, combined with elaborate stage spectacles impossible in any other theatre’. The building was the masterpiece of a genius of theatrical architecture, Frank Matcham. The centrepiece of this palace of marble, mosaic, gilt and terracotta was the great arena, which could be flooded with 100,000 gallons of water, or converted within sixty seconds to a dry performing space by raising up platforms which lay at the bottom of the artificial lake. For animal acts, shimmering grilles could be automatically raised, in moments, around the whole arena. In its first years the Hippodrome presented a unique combination of variety, circus and aquatic spectacle. As time went on, seats were built over the arena, and a more conventional style of variety took over.

There is a persistent but unlikely legend that Charlie was an extra in the first production at the Hippodrome, Giddy Ostend, which opened on 15 January 1900. At that time the Eight Lancashire Lads were playing in Sinbad the Sailor at the Alexandra, Stoke Newington. The Hippodrome Cinderella, which was produced by Frank Parker and ran from Christmas Eve 1900 until 13 April 1901, was more like one of the opulent ballet spectacles that made up the second half of the programmes at the Alhambra and the Empire Music Halls. The first half of the programme comprised eleven variety acts including Captain Woodward’s Seals and Sea Lions, Lockhart’s Elephants, Leon Morris’s Educated and Comedy Ponies, the Aquamarinoff troupe of Russian Dancers, equestrian acts, trapeze artists, Captain Kettle and Stepsons (comical acrobats), and Gobert, Belling and Filpe, ‘The Famous Continental Grotesques’. The ninth act on the bill was Gibbons’ ‘Phono-Bio-Tableaux’, an early attempt to combine sound with moving pictures. Cinderella was perhaps more a fairy play than a conventional pantomime. It was written by W. H. Risque, with music by George Jacobi, formerly the Alhambra’s Director of Music, and dances arranged by Will Bishop. It included five scenes and an aquatic display; and the setting for the ball was so elaborate that even with the Hippodrome’s stage machinery it required a pause of several minutes. The cats and dogs provided by the Lancashire Lads presumably figured in the scene ‘The Baron’s Kitchen’.

Buttons was played by the Spanish-born clown Marceline (1873–1927), who was to remain a regular favourite at the Hippodrome for some four years, at first billed as ‘Continental Auguste’ and later as ‘The Droll’. This young artist made a deep impression on the eleven-year-old Chaplin, as he described later in his autobiography; and it seems a reasonable speculation that professional contact and close observation of Marceline’s work was formative to his own subsequent conceptions of comedy. There is a distinctly ‘Chaplinesque’ quality in the bright-eyed little face that stares – sometimes soulfully quizzical, sometimes demonic – out of the few surviving photographs. Marceline’s hair and nose were red. He never spoke on stage – ‘one understood what he was up to more clearly by watching him than if he had brayed through a loudspeaker’66 – but he employed a repertoire of whistles (perhaps an inspiration for Charlie’s swallowed whistle in City Lights). His characteristic costume was a too-small tail coat held together in front by a piece of string, a white waistcoat and a broad bow tie. The grotesquely wide, short trousers were copied almost exactly by Chaplin for his musical act with Buster Keaton in Limelight. Below these, Marceline’s turned-out feet were encased in shoes that were too long and turned up at the ends. The whole was surmounted by a battered, cockaded tall hat, which was a focus for Marceline’s emotions: in moments of anger he would batter it in fury, but then a few moments later caress it with affection and respect. An exceptional acrobat, he would leap over a rank of eight men, after placing them in position with absurdly exaggerated precision. W. McQueen-Pope sums up his comic character:

… what he was up to was always interference, being a source of trouble to others and eventually to himself … He also laboured under the delusion that he was a born organizer. Let a carpet used by acrobats be in the course of removal, Marceline would rush to help. He would work like a beaver, push everyone about, create utter chaos and end up by being carried off, rolled in the carpet and struggling to be free.67

A sketch that Marceline presented in his 1900 Hippodrome season could well be the scenario of an early one-reel comedy film:

Marceline and his brother, the clown, receive a present of a wonderful marble statue. On turning a handle it moves into various striking attitudes, in one of which Marceline is actually struck by the statue. Marceline’s brother decides that they must have a photographer to take ‘lots of photographs, heaps of photographs’, and leaves his brother in charge while he goes to fetch the photographer. Marceline is told to dust the statue, and his nervous approach with a feather broom is very comic.

Marceline’s confidence grows as he dusts, and he puts the statue in such a number of ‘new positions’ that it finally breaks. Fearful of telling this to his brother, Marceline dresses up in a sheet, puts the statue’s helmet on (backwards) and seizes his sword and shield. Marceline, however, is not careful enough with the sheet and is discovered by his brother after some very comical imitations of the statue’s positions.68

Chaplin recalled in his autobiography how in Cinderella Marceline would perch on a camp stool beside the flooded arena, and fish with a rod for the chorus girls who had disappeared under the waves – anticipating Busby Berkeley musicals of later years. For bait he used diamond necklaces and bracelets. There is something perfectly Chaplinesque about the impertinence of angling in the Hippodrome’s spectacular arena, as there seems also to have been in the little poodle who shadowed Marceline’s every movement in the pantomime. After his brief years of glory at the London Hippodrome, Marceline faded into obscurity and committed suicide in 1927, at the age of fifty-four.

Chaplin also recalled from Cinderella his own first comic improvisations, in the role of a cat which had the privilege of tripping up Marceline in the kitchen scene. At one of the children’s matinées, he introduced some very unfeline comic business, sniffing at a dog and raising a back leg against the proscenium. According to Chaplin’s own account, the laughs were gratifying but repetitions were strictly forbidden. The Lord Chamberlain in those days was ever vigilant for any impropriety in music hall performances.

Chaplin’s explanation of his departure from the Eight Lancashire Lads was that William Jackson became tired of Hannah behaving like a stage mother and constantly complaining that her son looked peaky. If this were so, it would most likely have happened during the troupe’s prolonged London season at the Hippodrome. Perhaps there was some justice in Hannah’s fears. In 1912, Chaplin, then starring with the Karno troupe, told a Winnipeg reporter:69

Those were tough days sure enough. Sometimes we would almost fall asleep on the stage, but, casting a glance at Jackson in the wings, we would see him making extraordinary grimaces, showing his teeth, pointing to his face and making other contortions, indicating that he wanted us to brace up and smile. We would promptly respond, but the smile would slowly fade away again until we got another glance at Jackson. We were only kids and had not learned the art of forcing energy into listless nerves. But it was good training, fitting us for the harder work that comes before the goddess of success began to throw her favors around.

Despite Jackson’s grimaces and his way of massaging roses into small boys’ cheeks, Chaplin retained a feeling of wry gratitude towards him. In 1931, when he was in Paris, Chaplin met the Jacksons – William and his son Alfred – again. The old man was then over eighty but in very good form. Chaplin was touched when he told him, ‘You know, Charlie, the outstanding memory I have of you as a little boy was your gentleness.’

Hannah’s life, as usual, had not been easy during her son’s frequent absences from London. Her father, Grandfather Hill, was now sixty and had not been doing well since Grandma Hill had left him to go to the dogs. Gout and rheumatism had made it hard to work at his cobbling, and for some years he had been moving from lodging to lodging almost as frequently as his daughter. In July 1899 he became homeless and moved into Hannah’s little room in Methley Street. After five days he was admitted to Lambeth Infirmary, and after this spent a month or so in the workhouse. The return of Grandfather Hill into their lives might have had its compensations. Charlie remembered that during one of his infirmary periods, Grandfather worked in the kitchen and was able to smuggle bags of stolen eggs to his nervous grandson when he came to visit him.

While Charlie was appearing in Cinderella, Sydney decided to go to sea, taking advantage of the qualifications he had acquired aboard the Exmouth. He was still only sixteen, and seems to have added three years to his age to improve his prospects: throughout his seagoing career, his personal documents invariably gave his date of birth as 1882, instead of the correct 1885. On 6 April 1901 he joined the Union Castle Mail Steamship Company Line’s SS Norman, embarking on the Cape mail run. He was engaged as an assistant steward and bandsman on the strength of his aptitude with the bugle. Sydney was to make seven voyages in all, and after each his work and conduct were recorded on his Continuous Certificate of Discharge as ‘Very Good’.70 Throughout his life Sydney seems to have undertaken everything he did with the same conscientious zeal. More than thirty years after his first voyage, he recalled: