2

The Young Professional

Even at eleven or twelve, touring with William Jackson’s Lancashire Lads, Chaplin’s ambition to be a star was formed. ‘I would have liked to be a boy comedian – but that would have taken nerve, to stand on the stage alone.’1 With another of the Lancashire Lads, Tommy Bristol, he planned a double act, which they intended to call ‘Bristol and Chaplin, the Millionaire Tramps’. The idea never came to anything, but more than a decade later Chaplin was impressed to meet Tommy Bristol in New York, where he and a partner were earning $300 a week as comedians.2

Bert Herbert, a minor English variety comedian, remembered another project from this period, and there is enough circumstantial detail in his account to give it credibility:

After Charlie had left the Lancashire Lads my uncle brought him to our house (Thrush Street, Walworth), and asked my parents if they would agree to my brother and I joining another boy to tour as a dancing trio.

My people agreed, and Charlie took over his duties straight away. Charlie was an excellent dancer and teacher, but I am afraid we did more larking about than dancing – we were between ten and fourteen years.

Eventually we mastered six steps (the old six Lancashire steps) and got a trial show at the Montpelier, in Walworth, at that time, I believe a Mr Ben Weston was the proprietor.

I remember that we had no stage dresses, and went on in our street clothes. Charlie and my brother wore knickerbockers, and as I had long trousers I had to tie them up underneath at the knee to make them look like knickers.

How Charlie laughed when I went wrong, because one leg of my trousers started to come down as soon as I commenced to dance.

My uncle then went to America, and as we had no money to carry on, we had to let the Trio fall through. It was to have been called ‘Ted Prince’s Nippers’.

I lost sight of Charlie for some time, but I met him again when he was with Mr Murray in ‘Casey Court’ [sic] (a troupe of lads).

At the time I am speaking of Charlie lived in the buildings in Munton-road, off New Kent-road, and I rather fancy he went to Rodney-road school.

He certainly was not a ‘gutter snipe’. My mother used to admonish my brother and I with the remark, ‘Why aren’t you good like little Charlie? See how clean he keeps himself and how well behaved he is.’

Of course, I could have told her that he was as bad as us when she was out of the way, but then, as now, he could pull the innocent face at a moment’s notice.

I have heard it said that Charlie was always funny as a boy but, on the contrary, I found him just the reverse. I think he himself would bear out my statement.

His one ambition was to be a villain in drama. We often used to set a drama in the kitchen, and Charlie always wanted to be a villain. He certainly did not have awkward feet, as some people have suggested.

He was an ingenious kid. I remember often going to his house in Munton-road and playing with a farthing-in-the-slot machine, which he had made. It was an exact miniature model of the ‘penny-in-the-slot’ machines seen at fairs, etc., and worked admirably.3

Munton Road is not recorded anywhere else as an address for the Chaplins, but it is well within that small area of Lambeth and Southwark where Chaplin’s childhood was spent. If Bert Herbert’s recollection about ‘a Mr Ben Weston’ is accurate, it would place these incidents somewhere around Chaplin’s fourteenth birthday, in the early part of 1903, when Benjamin Dent Weston took over management of the Montpelier Palace in Montpelier Street, Newington, from Francis Albert Pinn.4

Quite suddenly young Charlie Chaplin’s luck changed. In fact, initiative and determination clearly had as much to do with it as luck. It must have required some nerve for the shy and shabby fourteen-year-old to register with one of the better-known theatrical agencies, H. Blackmore’s in Bedford Street, Strand. No doubt he already had the looks, vivacity and charm of later years, and made an impression: within a short time of his registering, the Blackmore agency sent a postcard asking him to call in about a job. He was seen by Mr Blackmore himself and sent off to the offices of Charles Frohman, whose wide-ranging interests as an impresario included management of the Duke of York’s Theatre in London; later Frohman was also to lease the Aldwych and the Globe and at one time had five London theatres under his control. He was to die in the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. Frohman’s manager, C. E. Hamilton, engaged Chaplin on the spot to play Billy the pageboy in a tour of William C. Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes, due to start in October. His salary would be £2 10s a week. Meanwhile, Mr Hamilton advised him, there was a likely part for him in a new play, Jim, A Romance of Cockayne, written by H. A. Saintsbury, who was to play Holmes in the forthcoming tour. Hamilton gave the boy a note to take to Saintsbury at the Green Room Club. To present himself in those august premises must have tested the boy’s nerve.

Saintsbury was a dedicated professional of the old Victorian touring school. Born in Chelsea on 18 December 1869, he came from a good middle-class background and had been educated at St John’s College, Hurstpierpoint. He started his working life as a clerk in the Bank of England, but was irretrievably stage-struck. At eighteen he appeared in Kate Vaughan’s revival of Charles Reade and Tom Taylor’s Masks and Faces, and soon afterwards became a professional. He toured in the standard repertory of Victorian melodrama – The Silver King, The Harbour Lights, The Lights o’ London, Under the Red Robe – as well as in classic parts. His great role, however, was Sherlock Holmes. Chaplin thought he looked just like the Strand Magazine illustrations of the great detective. Saintsbury was to play Holmes for almost thirty years, and for some 1400 performances. His own plays and adaptations reveal his romantic streak: as well as Jim, they included The Eleventh Hour, Romance (after Dumas), The Four Just Men, Anna of the Plains, King of the Huguenots and The Cardinal’s Collation.

Saintsbury clearly took to Charlie on sight, and handed him the part there and then. The boy was much relieved that he was not asked to read on the spot, because he still found it very difficult to make out words on the page. Sydney read the part for him, however, and in three days he was word-perfect. The brothers were amazed and moved at their good fortune. Sydney said that it was the turning-point of their lives – and promptly went off to Frohman’s office in an unsuccessful attempt to up Charlie’s salary.

Chaplin admired Saintsbury, and learned much about stagecraft working in his companies. Saintsbury, for his part, encouraged the boy. No doubt thanks to Saintsbury’s interest, Master Chaplin was generally mentioned in the press copy which the company sent each week to The Era. Unfortunately, Jim, A Romance of Cockayne was not a success. Its author described it as ‘an original modern play’, but it was very like Jones and Hermans’ old warhorse The Silver King, written twenty years before. Mr Saintsbury himself played Royden Carstairs, a young man of aristocratic lineage, inconveniently given to going off into cataleptic fits. Down on his luck, he is sharing a garret with Sammy, a newsboy – Chaplin’s part – and Jim, a flower girl who sleeps, for decorum’s sake, in a cupboard. The play is packed with dramatic incident, improbable coincidences, a stolen sweetheart, a long-lost child, a murder, false accusations, and a great deal of self-sacrifice.

As Sammy, Chaplin had a meaty supporting comedy role. His best scene is where he returns to the garret to find a detective searching the cupboard which is Jim’s quarters:

Sammy: Oi, you. Don’t you know that’s a lady’s bedroom?

Detective: What! That cupboard? Come here!

Sammy: The cool cheek of him!

Detective: Stow that. Come in and shut the door.

Sammy: Polite, ain’t you, inviting blokes to walk into their own drawing rooms?

Detective: I’m a detective.

Sammy: What – a cop? I’m off.

Detective: I’m not going to hurt you. All I want is a little information that will help to do someone a good turn.

Sammy: A good turn indeed! If a bit of luck comes to anyone here, it won’t be through the cops!

Detective: Don’t be a fool. Would I have started by telling you I was in the force? Sammy: Thanks for nothing. I can see your boots.

The critic of The Era praised the play (‘The dialogue is polished and epigrammatic, and the story of remarkable interest’) but neither his fellow critics nor the audience shared his enthusiasm. Jim opened at the Royal County Theatre, Kingston-upon-Thameson 6 July 1903, moved to the Grand Theatre, Fulham, for the following week, and closed finally on 18 July.

Chaplin, however, had earned his first press notices. Reviewing the first week, the Era critic wrote: ‘… mention should be made of … Master Charles Chaplin, who, as a newsboy known as Sam, showed promise’. Reviewing the Fulham performance, the critic praised him again: ‘Master Charles Chaplin is a broth of a boy as Sam the newspaper boy, giving a most realistic picture of the cheeky, honest, loyal, self-reliant, philosophical street Arab who haunts the regions of Cockayne.’

His best notice, though, was in The Topical Times, which ended its slaughter of poor Saintsbury’s play with a stroke of remarkable prescience:

But there is one redeeming feature, the part of Sammy, a newspaper boy, a smart London street Arab, much responsible for the comic part. Although hackneyed and old-fashioned, Sammy was made vastly amusing by Master Charles Chaplin, a bright and vigorous child actor. I have never heard of the boy before, but I hope to hear great things of him in the near future.

The premature demise of Jim seems to have hastened Sherlock Holmes into rehearsal and provided for one or two extra dates prior to commencing the main tour. Chaplin played Billy for the first time on Monday, 27 July 1903 at the Pavilion Theatre, Whitechapel Road. Seating an audience of 2650, this was an awe-inspiring place for a small, fourteen-year-old actor. The first provincial engagement was in Newcastle on 10 August 1903.

The management and Mr Saintsbury were concerned about the well-being of the youngest member of the company and decided that Mr and Mrs Tom Green, the stage carpenter and wardrobe mistress, should be his guardians whilst on tour. In his autobiography Chaplin said that by mutual agreement they abandoned this arrangement after three weeks: it was not, he said, ‘very glamorous’, the Greens sometimes drank, and it was tiresome to eat what and when they ate. He felt it was probably more irksome to them than it was to him. In fact, the shyness which was to remain characteristic may have led him to underestimate Mrs Green’s concern for him. Almost thirty years later she recorded her recollections of the period, and though she was a year out in her dating, in all other respects, where her anecdotes can be checked against verifiable facts, she appears a remarkably accurate witness. At the time she was interviewed, in 1931, she was living in Scarborough as Miss Edith Scales. Mrs Tom Green, she said, was her ‘stage name’, so the liaison with Tom the carpenter may have been just temporary and informal.

We opened our tour at the Pavilion Theatre, Mile End Road in July 1904 [sic]. I became his guardian a week later when we went to Newcastle to play at the Theatre Royal.5 Charlie was all right when we were in London because he was at home, but when we started touring he had no one to look after him. There was a matinée on the Saturday, but Charlie, who had failed to leave his address, knew nothing about this matinée, and when he did not turn up for the opening, we had to get his understudy into his clothes. The show had started when up came Charlie proudly carrying under his arm a five-shilling camera he had just bought. Poor boy, he started to cry when he heard he was late for the matinée, but I told him to dry his eyes and rushed off to get the understudy out of his clothes again. Charlie was not due on until the second act, and so I rushed him off into the ladies’ dressing room and we got him ready in time.6

The five-shilling camera which Chaplin had bought with his first week’s wages from Sherlock Holmes remained an interest for some time. He had retained the mercantile spirit developed during the hard times of his search for work in London, and set up as a part-time street photographer – it was a common itinerant trade at that time – taking portraits for threepence and sixpence a time. The sixpenny ones were framed: he had found a shop where he could buy cardboard frames for a penny. Miss Scales said that he generally sought out the working-class streets for his trade and that he did his own processing and printing:

Whenever we went to new rooms, Charlie would ask the landlady, ‘Have you got a dark room, ma?’

One landlady asked Miss Scales to fetch Charlie for his dinner, but she could not find him anywhere in their rooms upstairs, so she called out.

There was a knocking from inside the wardrobe, and Charlie’s voice: ‘Don’t open the door! You’ll spoil my plates if you do.’

I was very much annoyed, then he came out and I discovered he had burnt the bottom of the landlady’s wardrobe with his candle.

‘It will be jolly fine if she charges you for the damage before we go,’ I told him. ‘Don’t worry, she won’t notice it,’ said Charlie. ‘I’ll put a piece of clean paper in the bottom and cover it over.’ He did, and we heard no more about it.7

The Frohman tour proper began on 26 October 1903 at the Theatre Royal, Bolton. In the third week of the tour Miss Scales and Charlie found themselves in the magistrates’ court and the local papers, as witnesses of a fracas that sounds like a try-out for Dough and Dynamite.

They were playing at the Theatre Royal, Ashton-under-Lyne, and lodging with Mrs Emma Greenwood in Cavendish Street. On Tuesday, 10 November Mrs Greenwood was baking in the kitchen and Charlie was hovering. ‘Charlie was an expert at getting round landladies,’ Miss Scales remembered. ‘When it was baking day, they could never resist his appeals for hot cakes.’ Suddenly there was a loud knocking on the front door: it was a drunken chimneysweep called Robert Birkett who was notorious in the district for his violence and foul language. When Mrs Greenwood opened the door, he began to swear at her, told her her chimney was on fire, and insisted upon seeing it for himself.

Complainant said he came into the house and when he saw the fire he said, ‘Give me a lading can full of water.’ She said she had not a can, and gave him a jugfull. He threw the water on the fire to put it out. He said, ‘Give me another,’ and she did, which he also threw on the fire. He then said, ‘I will make you pay for this.’ She told him if she had to pay she would do so. He then said, ‘I want one shilling,’ and came out with bad language. She opened the door and told him he had to go out, as she would give him no shilling. The defendant then caught hold of her and pulled her into the backyard where he thrashed her shamefully. He got hold of her arms in front and kicked her legs. – Defendant: I never lifted my foot up. – The Clerk: How was he for drink? – Complainant: He was not sober and was not drunk. – Defendant: Didn’t you hit me with the poker? – Complainant: No. – Charles Chapman [sic], a boy, said he saw it all, and the complainant’s evidence was quite true.8

As Miss Scales recalled the incident, she had been resting in her room when Charlie rushed in, woke her, told her a man was attacking him, and rushed out again. ‘Of course, thinking a lot about the boy, I was off like a shot.’ She arrived in time to see Mrs Greenwood putting Bob Birkett out, ably assisted by Charlie, who was threatening him with a poker.

We were at Stockport the following Monday when they sent for us to appear in court, and we had to return to give evidence. Charlie first went into the witness box, but no one could understand his cockney accent. The sergeant kept touching him on the shoulder and saying, ‘Will you speak a little more clearly please.’ But Charlie was very excited and indignant about the man kicking the landlady. After a lot of fun he got his story out, however, and the man was sent to prison, I believe for about three months.

Then Charlie asked the sergeant, what about our expenses? The sergeant replied, there’s no fine and so there’s no pay. Charlie was very vexed, but despite his indignation at such treatment, the court allowed us no expenses. Charlie chattered and grumbled all the way to the station about this, and it took him a long time to forget it. ‘To think we have had to come all this way and pay our own fares,’ he complained.9

The week before this excitement in Ashton-under-Lyne, when the Sherlock Holmes company was playing in Wigan, Charlie had bought two tame rabbits, and Miss Scales’s Tom – ‘a very kind-hearted man’ – had made him a box covered over with canvas to keep them in.

Charlie had a great affection for his two pets, and kept them for several months. When one got worried, he vowed vengeance and searched all over for the cat or dog that had done it, walking through all the streets in the district, but of course he did not find it. He took the rabbits wherever we went, and when we were travelling he used to put them on the luggage rack and take the cover off the box to give them plenty of air. Once he let his rabbits run away in the landlady’s sitting room and of course they made a mess and annoyed the landlady. That was the only time I really had to chastise him. He could make those pets do all sorts of tricks.10

In his autobiography Chaplin mentions only one of his rabbits, which he says fell victim to a landlady with a cryptic smile. He remembered that this was in Tonypandy, which the Holmes tour did not hit until 3–8 April 1905, so the rabbit had retained his affection for seventeen months.

Miss Scales was constantly impressed by young Charlie’s financial acumen. On a later tour, in August 1905, she remembered:

One day, while we were at the Market Hotel, Blackburn, he went into the sitting room and delighted all the farmers by singing to them. It was market day and the place was full. He finished up by showing them the clog dance, and he could do that dance too. But the farmers had to pay for the entertainment. Yes, Charlie went round with the hat when he had finished. I got hauled over the coals for allowing him to do that, but I wasn’t there to stop him. But everyone liked Charlie. He was a wonderfully clever boy, and had wonderfully perfect teeth and hair. We had Robert Forsyth playing as Professor Moriarty in the company. He was a great friend of Charlie’s. Another friend of Charlie’s was H. A. Saintsbury … 11

When the time came to settle with the landlady, Charlie would carefully inspect the bill and knock out any item he had not had. ‘He allowed no overcharging. If he had been out to tea, for instance, he would deduct the amount chargeable for one tea from the bill.’12

This kind of touring must have been an extraordinary schooling in life for a bright boy to whom Hannah Chaplin had passed on her gift of observation. They toured all over Britain, from London to Dundee, from Wales to East Anglia. Mostly, though, they travelled through the sooty industrial towns of the Midlands and North – Sheffield, Blackburn, Huddersfield, Manchester, Bolton, Stockport, Rochdale, Jarrow, Middlesbrough, Sunderland, Leeds. At the time, even the smallest town had its theatre: including the Co-op halls and corn exchanges, there were well over 500 active professional theatres in the British Isles.

Despite Mr and Mrs Green, Chaplin remembered that he became melancholy and solitary while touring, and began to neglect his personal appearance. Meanwhile Sydney, whose theatrical aspirations had long pre-dated his brother’s but who had not yet succeeded in finding stage work, had taken a job as bar tender at the Coal Hole in the Strand (one of London’s first song-and-supper rooms, it had by this time reverted to the role of an ordinary pub). In December 1903, however, Charlie persuaded the Sherlock Holmes management to give his brother a part as Count Von Stalberg; and for the remainder of the 1903–4 tour, which closed on 11 June at the Royal West London Theatre in Church Street, Edgware Road, the brothers were together.

The casting of Sydney in an aristocratic – albeit foreign – role raises the question of the Chaplin brothers’ diction at this time. We have seen that Charlie’s cockney accent was so pronounced that he was hardly comprehensible in Ashton-under-Lyne (before the days of radio, people were generally less accustomed to regional accents different from their own). Even after his arrival in Hollywood, interviewers occasionally referred in passing to his ‘cockney’ accent. Later, as we know from the talking films, there was no trace of such an accent (although Georgia Hale recalled13 that around 1929 Chaplin was upset when Ivor Montagu referred to his ‘cockney’ accent). Sydney’s speech, on the other hand, retained evidence of his London origins to the end of his life. It might be supposed that an accent would be a handicap in a theatre committed to ‘correct’ English diction. Both in the music hall and the legitimate theatre, however, there was a formal ‘thespian’ style of speech, which the ordinarily accomplished performer could adopt as readily as he put on make-up. A good example of a stage accent was Gus Elen’s, whose song ‘’E Dunno Where ’E Are’ is supposed to have been Chaplin’s debut performance. Born in London, Elen retained a South London accent to the end of his life. He performed his coster songs with quite different diction, which still kept the Dickensian cockney’s interchange of ‘w’ and ‘v’. A gramophone record made at the time of his comeback in 1930, however, includes a speech of thanks to his public declaimed in full ‘thespian formal’. No doubt the Chaplin boys would have been thus equipped to rise to any role on the stage. The music hall style of ‘thespian formal’ is admirably demonstrated in Chaplin’s flea circus number in Limelight. The diction of the song he sings as the circus proprietor is remarkably like that of the famous music hall star George Bastow, performing ‘Captain Gingah’ or ‘Beauty of the Guards’.

For part of the tour the Chaplin family was reunited. Hannah had had one of the periodic remissions characteristic of her illness, and on 2 January 1904 was discharged from Cane Hill. For a week or two she joined her sons on tour. Charlie was both touched and saddened to find their relationship had changed. Hannah’s sons had ceased to be children, and she in her way had become a child. On the tour she did the shopping and cooking, and bought flowers for their rooms: Chaplin remembered that even at their poorest she would manage to save a penny for a bunch of wallflowers. But, he said, ‘She acted more like a guest than our mother.’ After a month, Hannah decided she should go back to London and rented the apartment over the hairdresser’s in Chester Street again. The boys helped her furnish it and sent her twenty-five shillings a week out of their earnings.

Some time before Hannah’s discharge from Cane Hill, the brothers had moved their London base from Pownall Terrace to smarter rooms in Kennington Road. Now that Hannah had a home again, they seem to have given up these new rooms. Chaplin confessed with slight shame and regret that when they stayed with her in Chester Street in the summer of 1904, after the close of the Sherlock Holmes tour, he secretly looked forward to the extra comforts they were able to enjoy in theatrical lodgings.

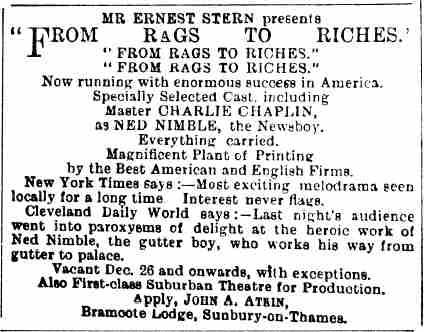

On 20 August 1904, just over two months after the end of the Holmes tour, the following advertisement appeared in The Era:

The critical quotes refer somewhat misleadingly to the play’s original American presentation. This British production, promising young Charles his first starring role, was apparently still only at the planning stage. The advertisement continued to appear through the rest of August and September and during the first two weeks of October, but there was no announcement of any engagements, so perhaps the production never progressed beyond rehearsals – for which, in 1904, the artists would almost certainly have been unpaid. Nevertheless, in his later days Chaplin spoke with some pleasure of the role.

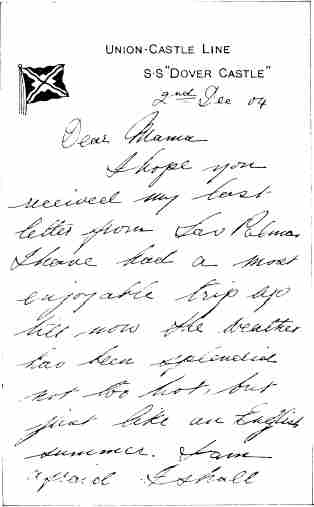

Next he was offered his old part as Billy in a new tour of Sherlock Holmes, starting on 31 October 1904. Sydney’s role was filled, so he went back to sea as assistant steward and bugler on the Dover Castle to Natal. He sailed from Southampton on 10 November and did not return until 19 January 1905.14 It was on this voyage that he discovered his gifts as a solo comedian. On 2 December he wrote home:

Union Castle Line

SS ‘Dover Castle’

2nd Dec 04Dear Mama,

I hope you received my last letter from Las Palmas. I have had a most enjoyable trip up till now. The weather has been splendid, not too hot, but just like an English summer. I am afraid I shall not make the money on these boats like I did on the Mail boats. I have done all right up till now. I had three passengers to Las Palmas. They gave me half sovereign between them, & when they had gone ashore, I had four more passengers 3 to Cape Town & one to Natal. I think they will all give me half sovereign each. I had to march in front of the Fancy dress ball procession with the Bugle & play a march, & then a couple of days after the Scotchmen all dressed in kilts & I had to blow them round the deck, so the sports committee have just called me into the smoking room & gave me 10/– not so bad is it? I have also made half a crown on the afternoon tea table, so altogether I can consider I have made £3–2–6. I have still got coast passengers to come yet besides my passengers home again so I may clear over £5. Thank God my health has been splendid & I do so hope your leg is better. Whatever you do take great care of yourself. I suppose the weather is getting very cold in London. I hope you will enjoy your Xmas. Try and get invited out somewhere. You don’t want to be too much alone. How is little Charlie getting on? I hope he is in the best of health and taking great care of himself. Give him my love tell him so. I hope he will have an enjoyable Xmas & send him heaps of Kisses for me and heaps for yourself. You will be pleased to hear that I made a terrific success at the concert on board. I gave an impersonation of George Mozart15 as the ‘Dentist’. They simply roard and would not let me off the platform until I had sung them ‘Two Eyes of Blue’. There is another concert on tonight and why [while] I am writing this they have sent down three people to ask me to oblige. They tell me the audience are shouting for the Bugler and the boy who has just got up to recite ‘The Boy stood on the Burning Deck’ has been hissed off. Fancy the quiet old Syd becoming a comedian. I have told them to tell the chairman I don’t feel up to it tonight. The fact is I have undressed. I am lying on my bunk in my pyjamas. It is best to leave them wanting. My histrionic [word illegible] have become the talk of the boat the last two days. Give my love to Grandfather. I shall go & see him when I come home. Remember me to Miss Turnbull give her my Xmas Greetings. Best Love and Kisses to your own dear little self,

From your loving son,

Sydney16

Charlie’s new tour of Sherlock Holmes began at the end of October. At this time Frohman had three Holmes companies on the road, designated as ‘Northern’, ‘Midland’ and ‘Southern’. Charlie was with the Midland company, with Kenneth Rivington in the role of Holmes, and was appearing in Hyde during the week of 6 March 1905 when news came of Hannah’s relapse. Neighbours had taken her to Lambeth Infirmary on 6 March. Three days later Dr Marcus Quarry examined her and concluded that she was ‘a Lunatic and a proper person to be taken charge of and detained under care and treatment … She is very strange in manner and quite incoherent. She dances sings and cries by turns. She is indecent in conduct & conversation at times and again at times praying and saying she has been born again.’17

1904 – Letter from Sydney Chaplin to his mother, written while at sea on the Cape mail run.

One week later, a Justice of the Peace, Charles William Andrews, signed the necessary Lunatic Reception Order, and two days after that Hannah was returned to Cane Hill. She was never to recover. On the statement of her particulars she was described as a widow and a stage artist (the boys’ success must have revived the old dreams) and her age was given as thirty-five – she was of course forty. Sydney must have been away from home, as the only name of a relative entered on the forms was that of her sister, Kate Hill, then living at 27 Montague Place, Russell Square. Charlie was unable to visit Hannah until the tour ended on 22 April.18 The homecoming must have been bleak.

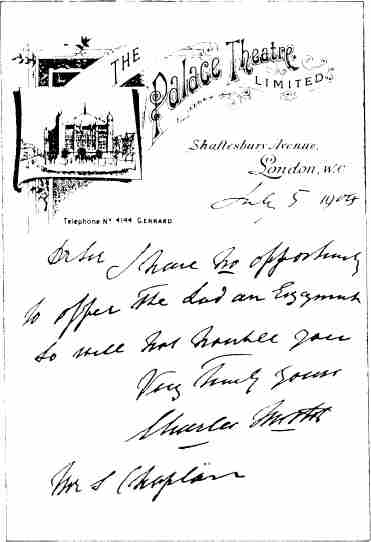

1904 – Letter from the great pioneer music hall manager Charles Morton, refusing Sydney’s request for an audition for Charles.

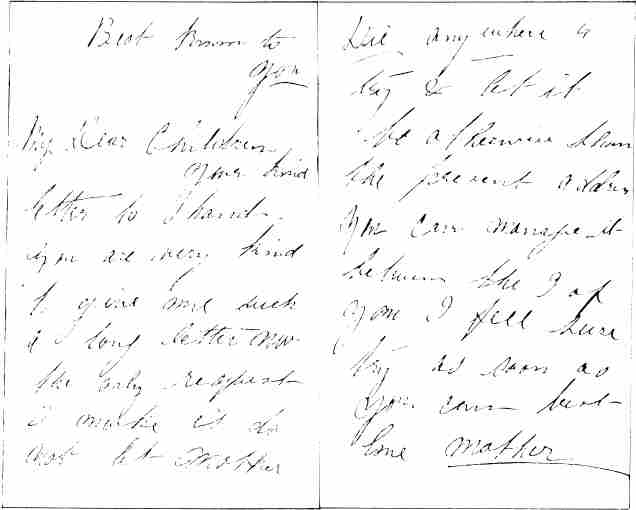

In Hannah’s lucid moments she would write to her children, and it is not hard to imagine the pain that her pathetic pleas must have given them. In one letter, she could not even bring herself to write the name of the asylum. This was evidently written soon after her arrival at Cane Hill. A few weeks later she seemed more resigned, even jocular: the uncharacteristic misspelling of the address may itself be an Old Testament joke:

Cain Hill Asylum

Purley

Surrey.

3/7/05My Dear Boys,

– for I presume you are both together by this time, altho Charlie has not written. Never mind, I expect you are both very busy, so I must forgive you. Oh, I do wish you had gone and seen about my (‘Ta–yeithe’) I mention this word as [illegible] know what I mean. Do see what you can do about them, as I am most uncomfortable without them, & if W. G.19 should pay me a visit on this coming Monday, I am afraid he will not renew his offer of a few years back & I shall be ‘on the shelf’ for the rest of my life, now don’t smile.

But joking apart you might have attended to small matter like that whilst you were in Town. Now I must draw to a close as it is Bedtime & broad daylight. Guess how I feel? Anyhow, good wishes & God Bless & prosper you both is always the Prayer of

your Loving Mother,

H. H. P. Chaplin.Send me a few stamps and if possible The Era. Do not forget this, there’s a dear.

Mum

Tons of Love & Kisses, for you both.20

1905 – Letter from Hannah Chaplin to her sons, written from the Cane Hill Lunatic Asylum. Instead of an address she writes, ‘Best known to you’.

Hannah’s request for The Era shows that she still liked to read about her old music hall acquaintances.

Charlie was out of work for fifteen weeks, but no doubt he had saved enough on his tours to support himself until August, when he was on the road again. The new tour was a distinct comedown. The touring rights of Sherlock Holmes had been taken over by Harry Yorke, lessee of the Theatre Royal, Blackburn, who had got together a pick-up company with one H. Lawrence Layton in the title role. Charlie was obliged to accept a reduced salary of thirty-five shillings a week, but had the consolation of being the seasoned pro of the troupe, laying down the law about the way things were done in the Frohman Company. He was aware that this precocity did not endear him to the rest of the cast.

The tour opened in Blackburn at Mr Yorke’s own theatre, then went on to Hull, Dewsbury, Huddersfield, the Queen’s at Manchester and the Rotunda at Liverpool. In the seventh week, when they were playing at the Court Theatre, Warrington, there came a miraculous reprieve in the form of a telegram from William Postance, stage manager to the celebrated American actor-manager William Gillette (1855–1937). Gillette was not only co-author, with Arthur Conan Doyle, of the dramatic version of Sherlock Holmes, but was also the greatest interpreter of the role. He had first played Holmes in New York at the Garrick Theatre on 6 November 1899, and scored a tremendous success with the play in London at Irving’s Lyceum, in September 1901.

Gillette had just returned to London with a new comedy, Clarice. His leading lady was the exquisite Marie Doro, who had played opposite him in New York the year before in The Admirable Crichton and had made a triumphant London debut in Friquet in January 1905. Clarice opened at the Duke of York’s Theatre on 13 September 1905. It was not a success. The London critics not only disliked the play but they disapproved of Gillette’s American accent. Gillette decided to reply with a joke, a little afterpiece to be called The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes, ‘a fantasy in about one-tenth of an act’, in which he would appear without speaking. The playlet had only three characters: Holmes, his page Billy and a mad woman. The idea was that, despite the efforts of Billy to keep her away from Holmes, the mad lady bursts into his room and talks incessantly and incoherently for twenty minutes, defeating all his efforts to get a word in. Holmes, however, manages to ring the bell and slip a note to Billy. Shortly afterwards two attendants come in and carry the lady off, leaving the last line to Billy: ‘You were right, sir – it was the right asylum.’ The unfortunate mad lady, Gwendolen Cobb, was to be played by one of the most gifted young actresses on the London stage, Irene Vanbrugh. Gillette required a Billy, and the Frohman office, who ran the Duke of York’s and were managing Gillette, had the very boy. Hence the telegram from Mr Postance.

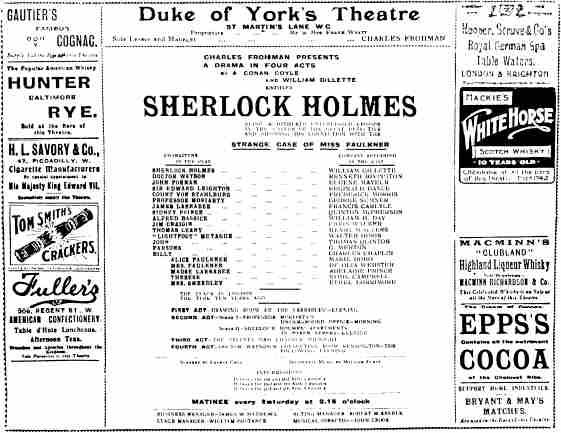

After his final Saturday performance in Lancashire, Charlie hurried to London, and after a couple of days of rehearsals was a West End actor. The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes went onto the programme on 3 October. Unfortunately Gillette’s good-humoured little joke still failed to save the day and the double bill ended its short run on 14 October, to be replaced after three days by a revival of the infallible Sherlock Holmes. Charlie, who had clearly made the same hit with Gillette as with everyone else with whom he worked, was kept on as Billy. Another veteran of the Frohman tours, Kenneth Rivington, who had played Watson to Saintsbury’s Holmes and had taken over the title role for the 1904–5 tour, was cast as Dr Watson. Marie Doro played Alice Faulkner for the first time; and the sixteen-year-old Chaplin fell desperately and agonizingly in love with this radiant young woman, seven years older than himself. The play repeated its original success: on 20 November there was a Royal Gala performance in honour of the King of Greece, who attended the show with Queen Alexandra, Prince Nicholas and Princess Victoria. Chaplin remembered that in a tense moment in the third act, when he and Gillette were alone on stage, the Prince was evidently explaining the plot to the King, whose strongly accented voice boomed out in agitation, ‘Don’t tell me! Don’t tell me!’

Saintsbury had taught the young Chaplin something of his stagecraft (one of his lessons, Chaplin recalled, was not to ‘mug’ or move his head too much when he talked). Working with Gillette provided other valuable tuition. Gillette was highly intelligent and very successful. His father was a senator and he himself had been educated at Harvard, the University of Boston and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Though his background was primarily intellectual, he brought an aggressively populist approach to the theatre, both as actor and playwright. The dramatist, he said, should not study dramaturgy, but the public. He held that the drama should be derived from observation of life and not from concerns about correctness of grammar, diction and aesthetics. He reacted against current melodramatic, declamatory conventions of acting, adopting a casual, downplayed style which suited light comedy rather better than love scenes. His guiding principle was that the actor must always strive to convince the audience that what he is doing he is doing for the first time. He set out this principle in an essay published in 1915, ‘Illusion of First Time Acting’.

1905 – Programme for Sherlock Holmes at the Duke of York’s Theatre.

Someone in the company, or in the Frohman office at this time, very clearly had Chaplin’s interests at heart: it may have been Gillette himself or Mr Hamilton or even William Postance, whom Chaplin remembered long afterwards with affection. (He was to call the kindly impresario in Limelight, played by Nigel Bruce, Mr Postant: this seems to have been intended as a tribute to Mr Postance, whose name is similarly misremembered as ‘Postant’ in the autobiography.) Two privileges which Chaplin enjoyed during the Duke of York’s run of Sherlock Holmes were certainly exceptional for a small-part child actor in the West End. He was procured a seat at the funeral of Henry Irving, which took place two days after Sherlock Holmes opened.

The funeral took place on October 19th, and a vast concourse assembled outside Westminster Abbey from an early hour, the signs of public mourning being as general as they were sincere and deep-seated. The Abbey itself was filled with a great and distinguished assemblage, including representatives of the King and Queen, eminent statesmen, and men and women renowned in art, literature and science, as well as in the profession of which Sir Henry Irving had long been the acknowledged head. The ceremony itself, with all the aids of a superb musical service, was profoundly impressive, and was conducted by the Dean and Canon Duckworth. The pall-bearers, who were assembled with the chief mourners round the coffin, included Sir Squire Bancroft, Lord Aberdeen, Sir A. C. Mackenzie, Sir George Alexander, Mr Beerbohm Tree, Sir L. Alma-Tadema, Professor Sir James Dewar, Mr J. Forbes-Robertson, Mr A. W. Pinero and Mr Burdett-Coutts, MP.21

And so, among the great and distinguished sat sixteen-year-old Charles Chaplin, who within a decade would have won far greater fame even than the departed actor-knight. He was seated, he recalled, between another celebrated actor-manager, Lewis Waller, and ‘Dr’ Walford Bodie, the current sensation of the music halls as hypnotist, healer and miracle worker. Chaplin was shocked by Dr Bodie’s unseemly behaviour, ‘stepping on the chest of a supine duke’ to get a better view as the ashes were lowered into the crypt.

A more remarkable achievement was that Chaplin managed to secure an entry in the first edition of The Green Room Book, or Who’s Who on the Stage. This was the forerunner of Who’s Who in the Theatre, but contained far fewer entries and so was more selective and prestigious. Hence it is remarkable to find listed among the aristocracy of the Edwardian stage:

CHAPLIN, Charles, impersonator, mimic and sand dancer; b. London, April 16th 1889; s. of Charles Chaplin; brother of Sidney Chaplin; cradled in the profession, made first appearance at the Oxford as a speciality turn, when ten years of age; has fulfilled engagements with several of Charles Frohman’s companies (playing Billy in ‘Sherlock Holmes’, &c.), and at many of the leading variety theatres in London and provinces; won 20-miles walking championship (and £25 cash prize) at Nottingham. Address: c/o Ballard Macdonald, 1, Clifford’s Inn, E.C.

There are other mysteries about this brief biography, apart from how Chaplin managed to make his way into The Green Room Book at all. The ‘impersonator, mimic and sand dancer’ presumably refers to talents acquired with the Eight Lancashire Lads; but does his ‘first appearance’ really mean his ‘first London appearance’, since he seems to have been with the Lads for at least three months before their seven-week season at the Oxford in April–May 1899, when Chaplin did, indeed, pass his tenth birthday. This, too, is the only known reference to the very substantial prize allegedly won in Nottingham, where Chaplin’s sole recorded appearance was in the week of 17 July 1899, again with the Lancashire Lads.

Sherlock Holmes might have settled in for a long run at the Duke of York’s had the theatre not been previously booked for the first revival of Sir James Barrie’s Peter Pan, with Cissie Loftus in the leading role. In the 1950s Chaplin finally squashed the long-standing legend that he played a wolf in this second production of the popular Christmas entertainment after Sherlock Holmes closed on 2 December. Instead, on 1 January he was on the road again with Harry Yorke’s touring Holmes company.

This was to be Chaplin’s farewell to the play after more than two and a half years. The tour opened at the Grand Theatre, Doncaster, then played Cambridge and four weeks around London – at the Pavilion, Whitechapel Road, where Chaplin had played Billy for the first time, the Dalston Theatre, the Carlton, Greenwich and the Crown, Peckham. The Era review of the Pavilion week mentions Sydney as a member of the cast, though it is not clear if this was an odd engagement or if he joined his brother for the entire tour. After a further week at Crewe and a week at Rochdale, the tour ended. Chaplin placed a ‘card’ in The Stage:

Master Charles Chaplin

SHERLOCK HOLMES CO.

Disengaged March 5th

Com. 9 Tavistock Place, Tele., 2 187 Hop.

Chaplin might have continued in the legitimate theatre but for a display of pride in the foyer of the St James’s Theatre, just before the end of the London run of Sherlock Holmes. Irene Vanbrugh’s husband Dion Boucicault gave him a letter of introduction to Mr and Mrs Kendal, who needed a boy actor for their 1906 tour of A Tight Corner. Madge Kendal swept in imperious and late for the appointment, and asked him to come back the next day at the same time, whereupon young Chaplin coolly retorted that he could not accept anything out of town and swept out, dignified but unemployed.

Fortunately Sydney was able to find him a job. Intoxicated by his success at ships’ smoking concerts, Sydney had decided that his future lay in the music halls and he joined the Charles Manon sketch company as a comedian. In March 1906 he was engaged by a new company set up under the management of one Fred Regina to tour a sketch, Repairs, written by the popular author and playwright, Wal Pink. It was advertised as ‘A New Departure – A Novel Item. WAL PINK’S WORKMEN IN REPAIRS. A brilliant example of “How NOT to do it”.’ The setting represented ‘The interior of Muddleton Villa, in the hands of those eminent house decorators, Messrs Spoiler and Messit.’ The idea of a gang of inefficient painters, paperhangers and plumbers was to be affectionately recalled in the slapstick paperhanger sketch in A King in New York. The plot, with Sydney as a heavily moustachioed and beery agitator endeavouring to get the slow-witted workmen to strike, looked forward to several two-reeler plots including Dough and Dynamite and Behind the Screen.

Sydney secured the part of plumber’s mate for his brother. He wore a green tam o’shanter which was an object of unreasonable irritation to the plumber. When instructed by the latter to hang it up, Charlie would knock a nail into a water pipe and soak himself. In exasperation, the plumber would seize the offending headgear, throw it to the ground and trample it in fury. Sydney told the journalist R. J. Minney that the sketch went well until they reached Ireland, where there was fury at the trampling of a green tam o’shanter. For subsequent performances a hat of different hue was substituted. A rare photograph of the sketch exists, which seems to show the plumber in the act of seizing a hat from Charlie. The seventeen-year-old Charlie himself stands with a red nose, clown-like make-up, short trousers, a hammer in his hand and a look of blank idiocy on his face.

Repairs opened at the Hippodrome, Southampton, on 19 March. It was extravagantly advertised with a full column in The Era, predicting a brilliant future for the act with a tour that would continue at The Duchess, Balham, the Zoo Hippodrome, Glasgow, and subsequently Boscombe, Belfast, Manchester, Wolverhampton, Liverpool, Portsmouth etc. In fact the show seems not to have lived up to expectations. Not all of these engagements can be traced and the advertisement was never repeated. After the week of 7 May, when Repairs was playing at the Grand Palace, Clapham, Chaplin left the troupe and his part was taken over by another youth, Horace Kenney (1890–1955), subsequently to become a music hall star in his own right.

Chaplin had answered an advertisement in The Era, announcing that boy comedians were required for Casey’s Circus, or the Caseydrome, which was shortly to be produced. It was a follow-up to Casey’s Court, an act that had already proved successful in the music halls. The setting for this was an alley, and the central figure, around whom a dozen or so juvenile comedians clowned, was ‘Mrs Casey’ – played in pantomime style by the comedian Will Murray (1877–1955), who continued to tour with the act until he was well into his seventies. Harry Cadle, the creator and impresario of the troupe, encouraged by the success of the original turn, now decided to establish and tour a second company with Will Murray again as leading artist and general director. Casey’s Circus was described as ‘a street urchin’s idea of producing circus’.

Chaplin appeared with Casey’s Circus in its opening week at the Olympia Theatre, Liverpool, from 21 to 26 May 1906. There is a story, without documentary corroboration, that he did a try-out with the original Casey’s Court at the Bradford Empire the previous week. There is, too, some uncertainty about the terms of his contract. In October 1927 the magazine Picturegoer claimed:

There is an interesting document still in existence dated May 26th 1906 which is the first legal document Charlie ever had. It is signed by his brother Sydney, as his guardian. In it he agrees to accept 45/= per week and his travelling expenses for his assistance in ‘anything connected with the performance of “Casey’s Court” that may be a reasonable request’.

In his book Chaplin, Denis Gifford quotes another circumstantial version of this alleged contract, without providing a source:

I, the guardian of Charles Chaplin, agree for him to appear in Casey’s Court wherever it may be booked in the British Isles only, the agreement to commence May 14th, 1906, at a salary weekly of £2.5s. 0. (two pounds five shillings) increasing to £2. 10s. 0.the week commencing July 1906.

Will Murray, for his part, reminisced fifteen years later:

I first met Charlie when I was running the sketch ‘Casey’s Court’. These sketches, which were pure burlesque, met with a great measure of success throughout the country.

To carry out a second edition of the sketch, I found it necessary to advertise for a number of boys between fourteen and nineteen years of age.

Amongst the applicants was one little lad who took my fancy at once. I asked him his name and what theatrical experience he had had.

‘Charlie Chaplin, sir,’ was the reply. ‘I’ve been one of the Eight Lancashire Lads, and just now [sic] I’ve got a part in the sketch [sic] “Sherlock Holmes”.’

I put him through his paces. He sang, danced, and did a little of practically everything in the entertaining line. He had the makings of a ‘star’ in him, and I promptly took him on salary, 30s. per week.22

Chaplin, whose memory for sums of money seemed infallible, remembered his salary as £3 a week. He also remembered that he was the star of the show and though the individual boys’ names were not billed, this seems to be confirmed by his placing, seated beside Mr Murray, in a group photograph of the troupe in 1906. Certainly he was given the two plum turns in the Circus. The act included a number of burlesques of current music hall favourites. ‘I particularly wanted a good thing made of Dr Bodie,’ remembered Murray. ‘Chaplin seemed the likeliest of the lot for the part and he got it.’

‘Dr’ Walford Bodie, whose indecorous curiosity had shocked Chaplin at the funeral of Sir Henry Irving, was at the peak of his celebrity. He was born plain Sam Brodie in Aberdeen in 1870, was apprenticed as an electrician with the National Telephone Company, but soon took to the variety stage as a conjuror and ventriloquist. By the time of his London debut at the Britannia, Hoxton, in 1903, he had developed a new and original act, billed as ‘The most remarkable man on Earth, the great healer, the modern miracle worker, demonstrating nightly “Hypnotism, Bodie force and the wonders of blood-less surgery”.’ He claimed, among other benefits to mankind, to have cured 900 cases of paralysis judged incurable by the medical profession. Those who revered him as a miracle man and those who regarded him as a fake alike acknowledged he was a great showman. He was a handsome man with a fine head of hair, an upswung waxed moustache and penetrating eyes. He appeared in a frock coat of exquisite cut and a gleaming silk hat. Chaplin studied his make-up from the photograph in Bodie’s advertisement in The Era and had a studio portrait taken of himself adopting the identical pose. ‘Rehearsals were numerous,’ remembered Will Murray,

and Charlie always showed a keen desire to learn. He had never seen Bodie’s turn, but I endeavoured to give him an idea of the Doctor’s little mannerisms.

For hours he would practise these in front of a mirror. He would walk for long spells backwards and forwards cultivating the Bodie manner.

Then he would ring the changes with a characteristic twist to the Bodie moustache, the long flowing adornment which the ‘Electric Spark’ affected, not the now world-famous tooth-brush variety … 23

Dan Lipton, a writer of comic songs who befriended the young Chaplin, confirmed that Chaplin had never seen Bodie in performance: ‘The way that boy burlesqued Dr Bodie was wonderful. I tell you he had never seen the man. He just put on an old dress suit and bowler hat, and as he marched onto the stage he swelled with pride.’24

When the act came south to the Richmond Theatre, The Era commented that ‘the fun reaches its height when a burlesque imitation of “lightning cures on a poor working man” is given’. Six weeks later, when the Casey’s Circus company played at the Stratford Empire, The Era noted that ‘an extravagant skit on Dick Turpin’s ride to York concludes the turn’. Chaplin was the star of this number also. Will Murray recalled:

… he ‘got’ the audience right away with ‘Dr Bodie’.

Then came ‘Dick Turpin’, that old invincible evergreen standby of the circus. It all went well, but the climax was the flight after the death of ‘Bonnie Black Bess’.

You can imagine the position of poor Mr Turpin. He had to run, hide, do anything to get out of the way of the runners, and yet he had nowhere to go except round the circus track.

Nevertheless, Charlie started to run – and run – and run. He had to turn innumerable corners, and as he raised one foot and hopped along a little way on the other in getting round a nasty ‘bend’ the audience simply howled.

I think I can justly say that I am the man who taught Charlie to turn corners. Yes, that peculiar run, and still more weird one-leg turnings of corners, which seems so simple when you see it carried out in the pictures, is the very same manoeuvre that I taught Chaplin to go through in the burlesque of Dick Turpin. It took many, many weary hours of monotonous rehearsals, but I am sure Charlie Chaplin, in looking back over those hours of rehearsals, will thank me for being so persistent in my instructions as to how I wanted the thing done.25

The Casey’s Circus tour ended on 20 July 1907, and Chaplin left the company. Young though he looked, he was probably already considered too old for a further season with a juvenile troupe. He was to be unemployed for three months. Sydney, however, was now in regular work. After leaving Repairs he had signed a contract with Fred Karno’s Speechless Comedians. In July 1907, by this time a major Karno star, he signed a new contract for a second year at £4 per week. No doubt, as he had done before, he helped his younger brother over this lean period.

In this spell between jobs, Charlie lodged with a family in Kennington Road and on his own admission lived a solitary, harum-scarum, boyishly dissolute life. He decided to work up a solo act as a Jewish comedian. Towards the end of the Casey’s Circus tour, in June 1907, he had played the Foresters’ Music Hall in Cambridge Road (formerly Dog Row), Bethnal Green. The management remembered his success as Dr Bodie and Dick Turpin, and agreed to let him do a week’s unpaid try-out. His material – he later realized that it was not only poor but anti-Semitic – and make-up and accent were not well calculated for the predominantly Jewish audience of the neighbourhood. The first and only night was a disaster, and Charlie fled from the theatre and the catcalls and pelted orange peel. This nightmare experience undoubtedly helped to instil in him an eventual dislike of working before a live audience. He was to have triumphant successes with the Karno Company, but it was evidently a tremendous relief when he was finally able to abandon the live theatre. Nothing would ever again persuade him to perform in front of an audience. In 1915 he told the actor Fred Goodwins, who was then working with him at the Essanay Studios: ‘Back to the stage! I’ll never go back to the stage again as long as I live. No. Unless my money leaves me, not ten thousand dollars would tempt me back behind the footlights again.’26 Very soon he was to be offered much larger sums than $10,000 but his decision was still unshakeable. More than fifty years later he told Richard Meryman: ‘On the stage I was a very good comedian in a way. In shows and things like that. [But] I hadn’t got that come-hither business that a comedian should have. Talk to an audience – I could never do that. I was too much of an artist for that. My artistry is a bit austere – it is austere.’27

Many great artists whose work depended upon the precision of a highly polished technique shared this mistrust of the unpredictable element offered by the audience. In the 1950s, the great music hall artist Hetty King, after almost sixty years’ stage experience, disliked following the still rumbustious Ida Barr in the veterans’ programme in which they were appearing: ‘I hate to follow that old woman. She gets the audience so unruly. I’m always terrified they will shout to me, talk to me. It throws me.’28 Max Miller, too, could be thrown off balance when audience reaction was not entirely predictable. It is possible that Chaplin had also inherited anxieties about audience reaction from his mother: fear of the public is a possible explanation of the lack of success of her career, despite her evident talents.

Not entirely daunted by the Foresters’ fiasco, he ‘tried authorship’ with a comedy sketch The Twelve Just Men – the title no doubt suggested by his friend Mr Saintsbury’s adaptation of Edgar Wallace’s 1905 novel, The Four Just Men. The twelve men of Chaplin’s plot were the jury deliberating a breach of promise case. Their discussions were complicated by the presence in their number of a dude, a deaf-mute, a drunk, a comedy Jew and a belligerent coster.29 Chaplin sold the sketch for £3 to a backer whom he identifies in his autobiography as ‘Charcoate a vaudeville hypnotist’ and who was presumably the illusionist ‘Professor’ F. Charcot (1870–1947). Chaplin was hired to direct it, and rehearsals began in a room over the Horns public house, but his backer pulled out after two or three days. The distraught teenager persuaded Sydney to break the bad news to the cast for him; in later years, when he was in command of his own studios, Chaplin could never bring himself to deliver ill tidings, like sackings and reprimands, in person, but always did it through intermediaries.

The Twelve Just Men mysteriously turned up in a variety bill at the Grand Theatre, Manchester, in the last week of May 1909,30 produced by a certain Fred Abbott and with no mention of an author; and at some point it was bought for £5 by the comedian Ernie Lotinga – one of the vaudeville troupe The Six Brothers Luck, and the first husband of Hetty King. Lotinga forgot about it until he came upon the manuscript again in 1932 and announced that he would produce this sketch written by Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin was understandably disconcerted at the prospect and offered to buy back the rights for $5000. Lotinga, reckoning he was on to a good thing, refused, whereupon the offer was raised to $7500. Lotinga still refused, proposing instead that he and Chaplin should go into partnership in the production, and that Chaplin should play the drunk. When this proposal aroused no enthusiasm, Lotinga announced that he would produce the sketch in the form of a musical revue and play the leading role himself. No more was heard of the project.

Half a century later, however, the script of Twelve Just Men came to light in a London auction room in a box of miscellaneous memorabilia that had evidently belonged to Lotinga. It was subsequently resold, catalogued as a Chaplin manuscript, to an unidentified buyer. The script was partly typed – perhaps to incorporate Lotinga’s revisions – and partly in a manuscript that was clearly not Chaplin’s but most likely Sydney’s. Most of the dialogue is excruciatingly unfunny, with stage directions indicating a good deal of violent knockabout. In style it is not unlike Sydney’s rather more polished dialogue for the later Karno sketch Skating; and the ‘dude’ is named ‘Archibald’, which was to become the habitual name for silly-ass characters (frequently played by one or other of the Chaplin brothers) in Karno sketches. This early effort at authorship most likely dates from between 20 July 1907, when Chaplin’s tour with Casey’s Circus ended, and February 1908, when he joined the Karno company, and his career began its unstoppable trajectory to stardom.