5

Essanay

Sydney arrived to start work at Keystone early in November 1914. He invented for himself a character called ‘Gussle’; padded out to a grotesque pear shape, he wore a curious little boat-shaped hat and a moustache, tight jacket and cane which seemed like homage to his younger brother. His first film, to be released in December, was Gussle the Golfer. As for Charlie, the Loew proposal which he had outlined in his letter to Sydney had eventually come to nothing. By the time of Sydney’s arrival in California he still had no firm offer from any other studio, and he was getting nervous. The apparent lack of interest may in fact confirm the persistent stories that Sennett made strenuous efforts to prevent representatives of other film companies from reaching Chaplin, hoping that he would eventually come, by attrition, to accept Keystone’s offer of $400 a week. Chaplin considered setting up his own production unit, but Sydney – to whom the film business as well as his own $200 salary was a startling novelty – opposed the idea.

Eventually, Chaplin received an emissary from the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company of Chicago, in the person of Jess Robbins, a producer and director with the firm. The name ‘Essanay’ was made up from the initial letters of the names of the founders, George K. Spoor and G. M. Anderson. Spoor had started in the film business as an exhibitor and renter in Chicago; Anderson (1882–1971), born Max Aronson, made his acting debut in The Great Train Robbery (1903) and later, as Broncho Billy, became the cinema’s first cowboy star. Spoor and Anderson went into partnership as Essanay in February 1907, taking as their trademark an Indian head, borrowed from the copper one-cent piece. Anderson established a little studio at Niles, near San Francisco, in 1908, where he set an unbeatable record by producing and starring in an unbroken series of 366 Broncho Billy films, turned out at the rate of one per week.

Anderson and Robbins had been greatly impressed by rumours that Chaplin was demanding $1250 per week and a $10,000 bonus on signing. Though the idea of the bonus was quite novel to him when Robbins mentioned it, Chaplin thought it best not to turn it down. Anderson agreed to the arrangement without consulting Spoor, who was greatly alarmed to learn that they would be paying about fifteen times the going rate for Essanay-featured players to a comedian of whom he had personally never heard. Chaplin signed, but became more and more suspicious when the $10,000 bonus failed to materialize. Poor Anderson was left to placate him since Spoor, who was supposed to hand the money over, had tactically disappeared from the Chicago studios.

Fortunately Chaplin liked Anderson, an amiable if taciturn westerner, who took him to visit Essanay’s little glasshouse studio at Niles. Chaplin decided he did not care for it, so in the last days of December 1914 Anderson accompanied him by train to Chicago, Essanay’s eastern headquarters, where the company had a studio at 1333 Argyle Street. Anderson returned to California on New Year’s Day, 1915, leaving Chaplin to discover, with no small dismay, the bitter cold of a Chicago January and the indifferent amenities of the studio. It still belonged to the first era of ‘film factories’. After the creative chaos of Keystone, Chaplin found the cold, production-line style of the Chicago studio inimical. The worst affront was when he was told to collect his script from the scenario department, whose chief at that time was the future queen of Hearst columnists, Louella Parsons.

Other irritations were in store. Neither Spoor, bonus nor salary turned up. Chaplin discovered that the Essanay staff had little or no concern for the quality of their product, while with the absurd, penny-pinching, pound-foolish bookkeeper mentality of the place, they recklessly screened and edited the negatives rather than pay the few dollars needed for proper positive rushes and working material. Some compensation was provided by the acting talent on hand in Chicago. Ben Turpin, a wizened little man, who resembled a prematurely hatched bird, with permanently crossed eyes and a prominent Adam’s apple dancing up and down his scrawny neck, was one of the best comedy partners Chaplin had ever found. Leo White was a lean, fierce, volatile little man who originally came from Manchester but had worked in operetta and specialized in characterizing comic Frenchmen with goatee beards and silk hats. Bud Jamison – a former vaudeville performer, baby-faced, six feet tall and weighing nineteen stone – provided the same grotesque physical contrast to Chaplin that Mack Swain had done at Keystone. Two pretty extras in Chaplin’s first Essanay film, Gloria Swanson and Agnes Ayres, were to become major Hollywood stars. Swanson played a stenographer: Chaplin was disappointed when he gave her a try-out for a more ambitious role but found her wooden and unresponsive. Years later Swanson told him she had been deliberately uncooperative, since she wanted to be a dramatic actress, not a comedienne.

We have a rare glimpse of Chaplin on the eve of starting work in Chicago. He was interviewed by Gene Morgan, a local reporter who was uncommonly perceptive and accurate in detail. One of his more striking revelations was that the legendary costume was at this period bought off the peg. Chaplin told him he had been shopping on State Street for a fresh costume and had had difficulty in getting boots large enough. He had also bought trousers. He told Morgan that he often followed people for miles to study character: ‘Fortunately my types are all small men. I would hate to be found following a big man and imitating him behind his back.’

Morgan’s summing up of the Chaplin personality deserves to be remembered, if only for the haunting final phrase:

You know him as a human gatling gun of laughs. He makes you chortle once every second. He has lots of flying black hair, and, do you know, it sort of grows on you. He wears an eloquent little moustache, which bounces on top of the funniest smile put on celluloid. He sports an unsteady derby hat, which he never fails to tip after kicking friends in the face. And he twirls a cane as if it were a blackthorn, Sousa’s baton, a carpet beater and a lightning rod, all in one.

And his feet –

You can’t keep your eyes off his feet.

Those big shoes are buttoned with 50,000,000 eyes.

Chaplin’s first film at Essanay was appropriately titled His New Job. As he had done in A Film Johnnie, he chose to set the action in a film studio. If nothing else this had the advantage that sets and props were ready to hand: at least he could limit his dependence on the Essanay scenic staff.

Chaplin was still the incorrigible Keystone Charlie, cheerfully causing chaos by his insouciant incompetence, tittering gleefully behind his hand at the spectacle of the destruction he has provoked, ever ready to apply a boot to the behind or a hammer to the head of anyone who presumes to protest. Chaplin clearly never worked out a scenario for the film. He adopted comedy props as they came to hand – cigarettes, matches, a pipe, a soda syphon, a saw and mallet, a swing door, a recalcitrant scenic pillar, an officer’s uniform many sizes too large and with accompanying shako and exceedingly bendy sword. He went through favourite routines with his cane (especially handy for hooking Ben Turpin’s feet from under him) and hat. On subsequent occasions he was to repeat and elaborate the business of being reprimanded for failing to remove his hat, which was introduced here. With childlike insolence he makes to replace the hat on his head and then at the last moment causes it to spring up into the air. He conscientiously searches the fur of the shako for fleas; and sizes up a piece of nude statuary with the affectation of disinterested connoisseurship he would later bring to the contemplation of the nude in the art shop window in City Lights.

After two weeks’ work, His New Job was ready for release on 1 February. By this time Spoor was back in Chicago, now happily reconciled to the idea of his new star. To his surprise, business colleagues had rushed to congratulate him on his good fortune; and now His New Job chalked up more advance sales than any previous Essanay picture. Chaplin finally received his bonus, but neither that nor Spoor’s strenuous efforts to make up for his previous offhandedness endeared him to his star. Unhappy with conditions in the Chicago factory, Chaplin announced that after all he would prefer to work in the company’s Californian studio: Niles was the lesser of two evils.

Since the historian Theodore Huff compiled the first Chaplin filmography in the late 1940s, Chaplin chroniclers have trustingly followed his assertion that the Essanay films were photographed by Roland Totheroh. In fact, Totheroh was not to become Chaplin’s cameraman until 1916. His most regular cinematographer at Essanay was Harry Ensign. Totheroh himself was wholly occupied on Broncho Billy films. He nevertheless remembered his first meeting with Chaplin at Niles: ‘We thought he was a little Frenchman.’1 Broncho Billy Anderson suggested that Chaplin might like to live in one of the studio bungalows as he did. Chaplin, however, was appalled by the mean and squalid style in which the millionaire star lived and soon moved to the nearby Stoll Hotel. Totheroh’s description of his arrival affords a vivid picture of the informal and rural character of film studios of the period, as well as the austerity of Chaplin’s own style of living in 1915:

We had a bungalow in the studio. I had a corner one, and later on Ben Turpin had the next one … And Anderson had one about a block down the road further, his own bungalow, you know. It was anything but a palace, he had an old wood stove in the kitchen and everything. So Charlie had one handbag with him – just a little old one of those canvas-like handbags, you know. Jim said, Charlie’s room will be this one here, and of course my room’s in front, whatever it was. And they were saying, We’ve got the old wood stove going in the kitchen, and we heated up some tea or something. We had Joe heat up some tea, you know. Charlie was an Englishman … So we opened his bag to put the things out. All he had in it was a pair of socks with the heels worn out and an old couple of dirty undershirts, and an old mess shirt and an old worn out toothbrush. He had hardly nothing in that thing. So we didn’t say anything. Joe said, Jeez, he hasn’t got much in this thing, has he? … I’ll never forget down there, nothing, he said, no bed and all this and that, and I felt like saying, yeah, and what the hell did you have? Jesus. Nothing in his handbag or anything.2

Years later, visitors to the Chaplin Studio would be no less surprised by the austerity of the star’s quarters.

Chaplin began to build up his own little stock company. From Chicago he brought Ben Turpin, Leo White and Bud Jamison. He also recruited a former Karno comedian, Billy Armstrong, and another English artist, Fred Goodwins, who had been on the legitimate stage after an early career as a newspaperman. Paddy McGuire came from New Orleans via burlesque and musical comedy but was typecast as an Irish bucolic. A key task, however, was to find a leading lady. One of Broncho Billy Anderson’s cowboys, either Carl Strauss or Fritz Wintermeyer, recommended a girl who frequented Tate’s Café on Hill Street, San Francisco. The girl was traced and turned out to be called Edna Purviance. Born in Paradise Valley, Nevada, and brought up in nearby Lovelock, she had trained as a secretary but (at least according to later publicity biographies) had done some amateur stage work. She was blonde, beautiful and serious and Chaplin was instantly captivated by her. Only after he had engaged her did he have some qualms as to whether or not she had any gift for comedy. Edna convinced him of her sense of humour at a party the night before she started work, when she bet him $10 that he could not hypnotize her, and then played along with the gag, pretending to fall under his spell. She was to appear with him in thirty-five films over the next eight years and to prove his most enchanting leading lady, with a charm exceeding even that of Mabel Normand. For some time their association, both professional and private, was to be the happiest of Chaplin’s early years.

Chaplin’s first film at Niles was A Night Out. If stuck for an idea, he could always rely upon a restaurant for inspiration: he ordered the construction crew to build a large café set, complete with a fountain in the foyer as an extra source of havoc. In this film Chaplin and Ben Turpin form a beautiful double act, sharing a solemn, unselfconscious, childlike air of mischief. It is an interesting variation on the partnership of Chaplin and Arbuckle in The Rounders. Charlie and Ben are a couple of drunks, absorbed in the tricky business of staying upright to the exclusion of all other proprieties. They are aggressive, whether loyally defending each other against interfering policemen, waiters and other hostile strangers, or fighting between themselves with fists and bricks.

Unlike His New Job, this comic pantomime depended upon comedy situations rather than comic incidents and props. It was so close to the Karno style that it is easy to imagine how it would have appeared on a theatre programme:

Prologue: Outside the Bar-Room

Scene 1: The Restaurant

Scene 2: The Hotel

Scene 3: The Other Hotel

In the prologue Charlie and Ben have an altercation with Leo White, as a frenchified man-about-town. In Scene 1, much the worse for drink, they meet Leo again in a restaurant and proceed to harass him and his lady friend until they are thrown out by a gigantic waiter (Bud Jamison). In Scene 2, Charlie flirts with a pretty girl in the room across the hall, until he discovers that her husband is the same hostile waiter. He decides to move to another hotel, but the couple have the same idea; and Scene 3 is the kind of hotel room mix-up (very piquant for 1915) that did service in Mabel’s Strange Predicament and Caught in the Rain.

Chaplin and Essanay still did not fully understand each other. Having completed shooting, Chaplin announced that he was going to San Francisco for the weekend. In his absence, Anderson, worried that they were behind schedule, asked Totheroh to help him edit Chaplin’s picture. According to Totheroh, Anderson’s notion of editing his own pictures was to take a close-up of himself rolling his eyes around and ‘use it in any place. He just measured it at the tip of his nose to the length of his arm, and then he’d tear it off, and that was his close-up. He’d shove it in.’3 Anderson and Totheroh had just started on the film when Chaplin, having changed his mind about the weekend, walked into the cutting room and told them, very forthrightly, to take their hands off his picture.

He took this opportunity to tell them also that in future he would not conform to the studio practice of cutting the negative but would insist on proper positive rushes. This required sending to Chicago for a new printer to be installed in the studio’s laboratory. When the new machine arrived and was installed, it proved to be missing a vital part, so this in turn had to be sent for. Anderson fretted at the delay in starting the third Chaplin film, but the director-star was adamant. Evidently the cutting-room incident did not permanently injure relations with Totheroh; a year later, when Chaplin took charge of his own studios, he invited him to join his staff.

Next, Chaplin set to work on The Champion. The studio lot served admirably as the setting for a boxing training establishment. Much of the action takes place in front of the board fence surrounding the studio, and we can also glimpse Essanay’s glass-house stage, the bungalows and the dusty, open countryside. For interiors, Chaplin needed only rough, hut-like rooms for the gymnasium. Like other Essanay films, this seemed to be a deliberate effort to retrieve opportunities lost at Keystone. Chaplin loved boxing at this time – going to prize-fights with members of his staff was his favourite leisure occupation – and he evidently found much satisfaction in developing the comedy business of The Champion.

Charlie is quite firmly established as a vagrant here: in the opening scene we see him on a doorstep, sharing his hot dog with his bulldog, a choosy pooch, who won’t touch the sausage until it has been properly seasoned. He decides to try his luck as a sparring partner, and to enhance his chances slips a horseshoe into his glove. The characters include a silk-hatted and moustachioed villain, straight from Karno’s The Football Match, who tries to bribe him; and the pièce de résistance is the championship bout that ends the film. Running for six minutes, it is balletic in composition, with Charlie devising a series of exquisite choreographic variations. At one moment the opponents fall into each other’s arms in a foxtrot.

The delay in getting the new printing apparatus extended the production of The Champion to three weeks. To make up, Chaplin dashed off In the Park within a week. Having found a park at Niles that looked very like Westlake, he reverted to the reliable old Keystone formula, with Charlie intervening in the affairs of two distinctly star-crossed lovers. The tramp is here at his least ingratiating. He is not only a pickpocket, but a cad as well. Having immobilized big Bud Jamison with a brick, he uses his victim’s open mouth as an ashtray. He even makes awful grimaces behind Edna’s back. Only one moment looks forward to the gallant Charlie of mature years. When Edna kisses him, he cavorts madly off under the trees in a satyr dance that anticipates Sunnyside and Modern Times.

Though Chaplin was never happy in the glass-covered studio at Niles, the open country around provided admirable locations for his next two films, A Jitney Elopement and The Tramp. The first was a conventional situation comedy with Charlie and Leo White competing for Edna’s hand. (Leo purports to be a French count and Charlie masquerades in the same role.) The film ends with a spectacular and imaginative car chase: at one point the cars, shown in extreme long-shot, waltz with one another. Chaplin also recorded for posterity the ingenious gag which Alf Reeves had admired when he saw him on stage as Jimmy the Fearless, and decided to recruit him for America. Attempting to take a slice from a French roll, Charlie continues in a spiral cut which turns the roll, in one of his most witty comic transpositions, into a concertina.

With this film, genuine romance begins to emerge in the love scenes. At our first sight of Charlie he is caressing a flower, as tenderly as the romantic vagabond of City Lights. Perhaps this new romantic element owed much to Chaplin’s growing relationship with Edna. A charming note has survived, dated 1 March 1915, from the time they were working on The Champion. Chaplin addresses his leading lady as ‘My Own Darling Edna’ and tells her that she is ‘the cause of my being the happiest person in the world’. He was evidently replying to a note which she had written to him:

My heart throbbed this morning when I received your sweet letter. It could be nobody else in the world that could have given me so much joy. Your language, your sweet thoughts and the style of your love note only tends to make me crazy over you. I can picture your darling self sitting down and looking up wondering what to say, that little pert mouth and those bewitching eyes so thoughtful. If I only had the power to express my sentiments I would be afraid you’d get vain …

The romantic element is still more pronounced in The Tramp. Made in only ten days, this remarkable film shows a staggering leap forward in its sense of structure, narrative skill, use of location and emotional range. Charlie is now clearly defined as a tramp. He saves a farmer’s daughter from some ruffians and subsequently foils the ruffians’ plot to rob the farm. The pet of the place, he falls in love with Edna but his happiness is crushed by the appearance of her handsome young fiancé. Charlie is disconsolate: his back alone expresses utter dejection. He departs from the farm, leaving a note:

I thort your kindness was love but it aint cause I seen him good bye

xx

For the first time, he makes his classic exit: he waddles sadly away from the camera up a country road, his shoulders drooped, the picture of defeat. But suddenly he shakes himself and perks up into a jaunty step as the screen irises in upon him.

Chaplin was anxious to get back to Los Angeles, and Anderson was hardly less anxious for his departure, since the Niles studio was proving too small to accommodate them both. The move caused a break in the flow of production, and the next film, By the Sea, has all the appearance of having been shot in a day – on the breezy sea front around Crystal Pier – to catch up on the schedule while the new studio was being made ready. It is the kind of scenario which would equally have served the commedia dell’arte or Keystone – a series of slapstick and situation variations skilfully managed within the restrictions of only nine camera set-ups.

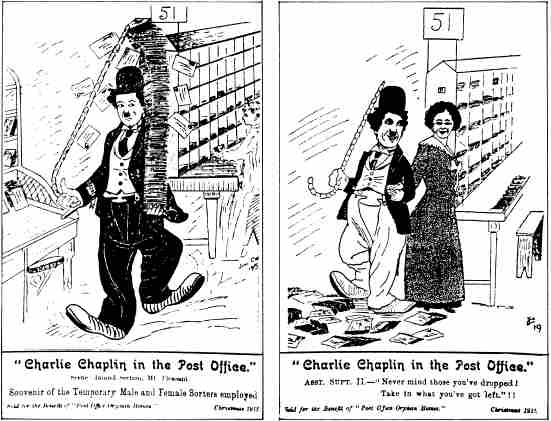

1915 – Two British postcards from the First World War: ‘Charlie Chaplin in the Post Office’.

Until this point Chaplin had respected the production-line methods of the time and maintained a steady rate of output. Now he declared his independence by taking much longer over his films. Twenty-seven days had elapsed between the release of A Night Out and The Champion; Essanay had to be content to wait still longer for subsequent releases. By the Sea was issued on 29 April 1915; Work did not appear until 21 June. The delay may in part be attributable to moving studios. For Work Chaplin temporarily took over the converted Bradbury Mansion at 147 North Hill Street, whose imposing approach serves for the exterior of the house seen in the film.

Some aspects of Work place it among the most remarkable comedies made up to that time. It appeared four months after D. W. Griffith’s revolutionary Birth of a Nation, and within its circumscribed form and ambitions is just as original. Painters, plumbers and paper-hangers had been the stuff of slapstick in the music halls for years:

When Father papered the parlour,

You couldn’t see him for paste.

Dabbing it here,

Dabbing it there –

Paste and paper everywhere.

Mother was stuck to the ceiling,

Kids were stuck to the floor.

You never saw a blooming fam’ly

So stuck up before.

Sydney and Charlie had appeared in Wal Pink’s Repairs, and Karno toured a sketch called Spring Cleaning. Chaplin would later introduce paper-hanging sketches into The Circus and A King in New York.

The basic notion of Work is that Charlie and his boss (Charles Insley) are decorators come to do up a middle-class home. This gives rich scope for all the traditional business with planks, ladders, paste and paint. Charlie wrestles with sticky and disintegrating wall-paper and transforms a peaceful parlour into a quagmired battlefield. The situation is the richer since the household consists of a tetchy little husband (Billy Armstrong), angrily protesting because his breakfast is late; a flamboyant wife (Marta Golden), en déshabillé and rocketing around the house giving artistic instruction to the glazed-eyed workmen; a pretty but inactive maid (Edna) and a gas stove given to periodic explosions. The mistress also has a secret lover (Leo White in French count style) who comes calling with flowers at the most awkward moment and has to be passed off, improbably, as one of the workmen. No opportunity for insult or assault with all the tools of the decorator’s trade is allowed to pass. The grand finale is a massive explosion which leaves the heads of various members of the ménage protruding from the rubble, Charlie’s boss submerged in the bath, and Charlie himself feebly emerging from the guilty oven.

It is the introduction to this delirium of destruction that makes the film most memorable. Our first sight of Charlie is as he advances towards the camera down a busy city street, harnessed to a cart piled high with ladders, boards and buckets. The boss sits on the driver’s seat, flicking at him with a whip. The cart gets stuck on the tramlines: Charlie drags it clear in the nick of time. He attempts a hill, but the cart again slides back into the path of an oncoming tram. In silhouette, we see Charlie hauling the cart up the side of a 45-degree incline. The weight of the cart raises the shafts in front, with poor Charlie dangling helplessly in the air. The boss thoughtfully offers a heavyweight friend a lift, and Charlie must now drag the two of them. He disappears down an open manhole, but is hauled back, hanging on to the shafts and counterweighted by the cart. This series of haunting, grotesque, horror-comedy images of slavery is presented with a degree of audacity and invention in the visualization that was hardly to be challenged until the Soviet avant-garde (idolaters of Chaplin) a decade later. The closest approximation to these first scenes of Work is to be found in Alexander Medvedkin’s 1934 satire, Happiness. Chaplin’s aims in inventing the sequence were no doubt uncomplicated: it is funny, and it prepares the audience to accept as his proper deserts the ill-treatment that the boss will later receive at Charlie’s hands. Yet, almost incidentally to his purposes, he has created a masterly and unforgettable image of the exploitation and humiliation of labour, the reverse of the Victorian ideal of the salutary virtues of work.

It was such aspects of Chaplin’s vision that touched the hearts of the great mass audience of the early twentieth century. There is another memorable moment of comic irony in a gag that sums up the ineradicable mistrust between middle and working classes. The lady of the house, having left the workmen alone in her dining room, suddenly remembers ‘My silver!’ She rushes back and fixes them beadily with her eyes as she hastily gathers up her treasures and packs them into the safe. They watch her in cool amazement. Then, without a word, they carefully remove their watches and money from their pockets. These valuables are carefully placed in Charlie’s right-hand trouser pocket. With his gaze mistrustfully fixed all the time on the woman, Charlie takes a safety pin and firmly secures the pocket.

Chaplin now moved into the old Majestic Studio on Fairview Avenue. Here he performed his third, last and best female impersonation, in A Woman. It was a tempting exercise: female attire suited him disturbingly well; the role gave scope for a whole new range of character mime; and Julian Eltinge’s sophisticated female impersonations had brought the genre into vogue and given it respectability.

The female impersonation is remarkable: it was no small tribute that the film was banned in Scandinavia until the 1930s. Perhaps the most memorable image of the film is Charlie without moustache, hat or trousers, suddenly transformed by the ‘woman’s’ fox fur (= a ruffle), long pants (= tights) and striped underclothing (= knickerbockers) into a traditional clown figure – a guise in which he was briefly to appear again, many years later, in Limelight. Critics of the time were distracted from the charm and unforeseen poetry of the image by their disapproval of the film’s improprieties. The pin-cushion bosom and the defrocking stirred a good deal of prudish protest, as did a throwaway scene in Work where Charlie puritanically covers the nakedness of a statuette with a lampshade, but then wiggles the lampshade to turn the figurine into a hula dancer. Chaplin was stung by charges of ‘vulgarity’. Fred Goodwins wrote at the time:

His fame was at its zenith here in America when suddenly the critics made a dead set at him … They roasted his work wholesale; called it crude, ungentlemanly and risqué, even indecent … the poor little fellow was knocked flat. But he rose from his gloomy depths one day, and came out of his dressing room rubbing his hands. ‘Well boys,’ he said, with his funny little twinkly smile, ‘let’s give them something to talk about, shall we? Something that has no loopholes in it!’ Thus began the new era in Chaplin comedies – clean, clever, dramatic stories with a big laugh at the finish.4

The Bank was not only a response to adverse criticism, however. Chaplin had been greatly struck by the praise he had received for The Tramp, with its strong injection of sentiment and surprise shift of mood at the fade-out. Now he set out to emphasize the sentimental element still further. Working with Edna required no pretence in the love story. Again, The Bank gave him an opportunity to rework an idea only partially realized in the hurly-burly of Keystone. The basic story is the same as The New Janitor. Chaplin once more introduced the dream device from Jimmy the Fearless. Charlie’s dreams of adventure and romantic success must remain merely dreams; the reality of the Little Fellow allows of no such escape from poverty.

The film opens with a surprise twist. Charlie enters the great city bank, descends to the vaults, makes great play with the combinations of a giant safe which he opens to produce – a pail, a mop and a janitor’s uniform. Charlie the janitor is hopelessly in love with the pretty secretary, Edna, but her heart is set on another Charlie, the suave cashier. The janitor falls asleep and dreams that he rescues the fair Edna from a gang of bank robbers: he presses her to his side and caresses her hair, but wakes to find it is the mop he has in his arms. The reawakened Charlie, spurned, wanders back into his vaults, past Edna and her cashier, who are oblivious to his presence. He still holds in his hand the rejected bouquet he had brought her. He tosses it down, gives it a kick, shrugs his shoulders and quickens his funny walk as he leaves us, and the camera irises in.

A comedy with a sad end was something new. The scenes in which Charlie, with tragedy in his wide eyes, watches Edna contemptuously throw aside his floral token of love touched depths of pathos quite unfamiliar in film comedy. It was from this time that serious critics and audiences began to discover what the common public had long ago recognized, that Chaplin was something new, and unique.

Fred Goodwins recorded a rare, brief impression of Chaplin at work with his actors on The Bank:

We had a scene in the vault – a burglary, with a creeping, noiseless entrance. All the time Chaplin sat beside the cameraman, whispering, almost inaudibly, ‘Hush. Gently boys: they’ll hear us upstairs!’ It is infectious, it gets into the actors’ systems and so ‘gets over’ on the screen.5

It was far from easy to come up with new ideas for films, but Chaplin knew that a good setting or prop would at once set his imagination working. For Shanghaied he rented a boat, the Vaquero, which suggested a neat plot and a lot of funny business. Charlie is hired to shanghai a crew, but finds himself shanghaied as well. Moreover, his loved one, Edna, has stowed away and the owner, Edna’s father, has plotted to sink the ship for the sake of the insurance.

The ship proved a marvellous prop. To simulate its rocking motion, the cameraman, Harry Ensign, developed a pivot on which the camera could swing, controlled by a heavy counterweight. Chaplin also had a cabin built on rockers so that he could realistically recreate the hazards of a storm-tossed ship. Mal de mer was to remain a favourite joke: it figured in Chaplin’s very last appearance on the screen, more than half a century later. The shipboard gags were also to provide prototypes for the first half of The Immigrant.

A good idea, he decided, will never wear out, so next he adapted his old Karno success Mumming Birds to the screen, as A Night in the Show. There is no evidence of any formal arrangement with Karno over the copyright, which is surprising since Karno was notoriously jealous of his properties, and in 1907 had brought an unsuccessful action against the French company Pathé for plagiarizing Mumming Birds in a film which had Max Linder as the drunk.

Chaplin added new material, set in the foyer and auditorium of a theatre: a flirtation with Edna, altercations with the orchestra, much changing of seats, and the precipitation of a fat lady into the foyer fountain. Chaplin also played a second role, Mr Rowdy, an outrageous tipsy working man in the gallery. This new character is forever needing to be rescued by his neighbours from tumbling into the pit below, and enthusiastically pelts the performers with rotten tomatoes. Finally, anticipating King Shahdov in A King in New York, he turns the fire hose on the fire-eater.

In his last days at Essanay, Chaplin was reported to be working on a feature film called Life, which was apparently to mark a new level of realism in his comedy. The project was abandoned, but the time Chaplin spent on it may explain the long delays between the release of The Bank and Shanghaied (fifty-six days) and between Shanghaied and A Night in the Show (forty-seven days). Some ideas and material shot for Life, notably a fragmentary sequence in a dosshouse, were later incorporated into Police (March 1916).

Chaplin’s critics had confirmed his own growing recognition that the Charlie character acquired definition and dimension from the reality of his situations and milieu. Charlie belongs to the dirt roads and mean urban streets, and the solitude of vagrancy. The dosshouse scene is a tantalizing glimpse of what Chaplin may have intended in Life. There is a Cruikshankian touch of the macabre about the place. A remarkable troupe of derelicts includes a befogged old drunk, an unshaven heavyweight whose first menacing appearance is belied by a display of mincing effeminacy, a broken-down actor, and a lean consumptive whose sunken cheeks and hacking cough Charlie callously impersonates when he perceives that such suffering is good for a free bed.

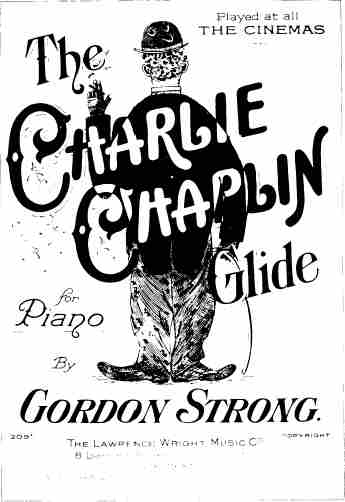

1915 – Music sheet, ‘The Charlie Chaplin Glide’.

There is also a new vein of irony. Police opens with Charlie coming out of prison. The title ‘Once again into the cruel, cruel world’ looks forward to Modern Times and Charlie’s efforts in that film to get back to the security and protection of jail. There is a foretaste, too, of later scepticism in the face of formal religion and its bigotries. Outside the prison gates Charlie meets a clergyman who begs him to ‘go straight’. Within moments the man of the cloth has not only filched Charlie’s last cent but also pocketed the watch of a drunk which Charlie had passed up – easy pickings as it was – on account of his new-found, if temporary, Christian morality. The next cleric who offers help in going straight is swiftly seen off for his pains.

Chaplin’s last film for Essanay was his sole essay in a style of parody then current. It was eventually released as Charlie Chaplin’s Burlesque on Carmen. Carmen was the current rage of Hollywood. Sam Goldwyn (then still Sam Goldfish) and his brother-in-law Jesse Lasky had lured the beautiful, thirty-three-year-old star of the Metropolitan Opera, Geraldine Farrar, to Hollywood with a salary of $20,000 for eight weeks’ work, plus motor car, house, servants and groceries. Her extravagantly publicized first film was Carmen, directed by Cecil B. DeMille and adapted from Merimée and Bizet by DeMille’s brother William.

DeMille’s film was ready in October 1915, and was swiftly followed by a rival version directed by Raoul Walsh for William Fox, and starring the sultry Theda Bara. In the Essanay version, Don José, as played by Chaplin, became Darn Hosiery, with Edna as Carmen, sent by the smuggler chief, Lilias Pasta (Jack Henderson), to seduce this strutting Captain of the Guard. The film was due for release in December 1915, but after Chaplin’s departure the company decided it would be more profitable as a feature than as a two-reeler. Leo White was called in to direct some completely new scenes with a new character, Don Remendado, played by Ben Turpin; Chaplin’s scenes were extended by salvaging his out-takes, and by the time of its eventual release on 10 April 1916 the film had grown to four reels. The horror of it sent Chaplin to bed for two days. The rambling, shambling knockabout of the film shows, by contrast, how taut and well-edited Chaplin’s own films had become. Some good things of Chaplin remain: the duel between Darn Hosiery and his rival of the Civil Guard (Leo White), though clearly longer and untidier than Chaplin intended it, contains some wonderful balletic passages. Audiences and serious critics were equally startled by the death scene, in which the hero stabs Carmen and then kills himself, and which was a good deal more realistically and movingly played than most genuine tragic death scenes of the period. Having shocked and silenced his audience with this scene, Chaplin then revealed how they had been fooled. His bottom suddenly twitches back to life and he and Edna get up, laughing, to demonstrate the collapsing prop dagger with which the deed had been done.

These odd moments did not vindicate the mangled film, however, and Chaplin looked for recourse in the courts. In May 1916, through his lawyer Nathan Burkan, he applied for an injunction to prevent Essanay from distributing Charlie Chaplin’s Burlesque on Carmen, claiming that he had not approved of the play; that his author’s rights had been infringed; that it was a fraud upon the public; that his own role in the film had been garbled and distorted; and that he would be damaged by the production. The plea was heard on Monday 22 May before Justice Hotchkiss of the Supreme Court, State of New York. Chaplin’s application for an injunction was dismissed and Justice Hotchkiss stated:

Whether plaintiff will suffer any damage from the production is problematical, while an injunction is certain to work loss for defendants.

While Nathan Burkan threatened that Chaplin would appeal to the Supreme Court and ask for a further $100,000 in damages, Essanay claimed for the recovery of half a million dollars’ damages against Chaplin. The grounds of this counter-suit were that in July 1915 Chaplin agreed to ‘aid in the production of’ ten two-reel comedies before 1 January 1916. For each of them he was to receive a bonus of $10,000 over and above his salary of $1,250 a week. One of the number was already completed: the company nevertheless retrospectively gave Chaplin his $10,000 bonus. (This must refer to Work.) Chaplin himself had decided that these comedies could be produced at the rate of one every three weeks. However, he completed only five two-reel pictures before leaving the company, receiving the $10,000 bonus on each. ‘The remaining four Chaplin failed to appear in, although the Essanay Company was prepared and still is ready to proceed with the making of these pictures. Under this arrangement the Burlesque on Carmen was produced and paid for.’ The company’s claim of $500,000 was based on the estimated lost profit of $125,000 on each of the four films not made.

Justice Hotchkiss’s ruling was encouraging enough for Essanay to prepare a further ‘new’ Chaplin comedy, three years after he had left the company. Two sections from the unfinished Life were retrieved. In one, Edna is a downtrodden housemaid, desperately scrubbing floors, while Charlie is the kitchen boy. The second is evidently a continuation of the dosshouse scene in Police: the old drunk has now become vocal and requires to be sedated with a bottle expertly applied to his cranium; a mad, vampiric sneak-thief filches from the other inmates. The scene has a wonderfully sinister quality, but it counts for little in the hotchpotch which Essanay concocted and called (for no good reason) Triple Trouble. Leo White was again engaged to direct additional scenes – a framing story about German spies, led by White himself, endeavouring to steal an inventor’s powerful new explosive device. White was not without style: he enjoyed using groups of people moving in formal, geometrical fashion, and he quite ingeniously welded the old and new material. In one scene Charlie the kitchen boy throws a pail of garbage over a fence in sunny California, 1915; it lands on the other side, in wintry Chicago, 1918. All in all, the film was a travesty. Chaplin had learned his lesson, however, and this time did not seek legal recourse.

Essanay continued until 1922 to press their claim on account of the alleged revised agreement of July 1915. In 1921 Spoor brashly proposed that he would settle the case in exchange for distribution rights in The Kid – an arrangement which would have required Chaplin to break his current contract with First National. Sydney curtly answered, ‘Nothing doing.’ Chaplin’s initial dislike of Spoor seemed vindicated when Spoor threatened that if necessary he would start a scandal relating to poor Hannah, still in the care of the Peckham House nursing home. Spoor claimed that his brother in England had advanced money to Aunt Kate Mowbray to pay the Peckham House bills, and that the money had not been returned. Kate was dead by this time, and so could not deny Spoor’s charges. Sydney wrote to his brother on 1 April 1922 to confirm that Kate had indeed borrowed money from Spoor’s brother, but that it had been returned and that he had receipts to prove it. The situation had arisen in May 1915, when payments to Peckham House became so overdue that the nursing home threatened to send Mrs Chaplin back to Cane Hill at the charge of the Board of Guardians. The Lambeth Settlement Examination Book recorded:

Chaplin, Hannah Harriet, Widow. Has been Private Patient in Peckham House since 9th Sept 1912. Sent to Cane Hill by Lambeth 18th March 1905. 2 Sons, Sidney and Charles Chaplin were subsequently discovered earning large salaries as Music Hall Artists – with motor cars of their own &c.

Owing to payments lapsing at Peckham House where the sons had their mother transferred as above, Peckham House apply under Sec 19 for the woman to be placed on Parish Class.

Mrs Mowbray, sister, now of 4 Coram Street Bloomsbury states that possibly owing to the war and sons Charles and Sidney moving about America, they have not been able to send.

These sons are now prominent Cinema Artists Charles earning about £70 per week with the Essanay and Keystone Producers and Sidney about £40 per week and no difficulty will be experienced if patient again sent to Cane Hill. Patient has expressed a wish to go there … 6

The Peckham House receipts have survived and show that Hannah’s sons were conscientious but irregular in remitting their weekly thirty shillings. The pressure of their work and the uncertain wartime post across the Atlantic were contributory factors. So Kate, desperate to prevent her sister being sent back to Cane Hill, had sought the then willing help of the Spoors. She could hardly have foreseen the mean advantage Spoor would later take from the incident.

Chaplin was, during this period, so tied up in his work at Essanay that he was almost the last to realize the extent of his phenomenal popularity. The year 1915 had seen the great Chaplin explosion. Every newspaper carried cartoons and poems about him. He became a character in comic strips and in a new Pat Sullivan animated cartoon series. There were Chaplin dolls, Chaplin toys, Chaplin books. In the London version of the revue Watch Your Step Lupino Lane sang ‘That Charlie Chaplin Walk’:

Since Charlie Chaplin became all the craze,

Ev’ryone copies his funny old ways;

They copy his hat and the curl in his hair,

His moustache is something you cannot compare!

They copy the ways he makes love to the girls,

His method is a treat;

There’s one thing about Charlie they never will get,

And that is the shoes on his feet.

It doesn’t matter anywhere you go

Watch ’em coming out of any cinema show,

Shuffling along, they’re acting like a rabbit,

When you see Charlie Chaplin you can’t help but get the habit.

First they stumble over both their feet,

Swing their sticks then look up and down the street,

Fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers,

All your wife’s relations and a half dozen others,

In London, Paris or New York

Ev’rybody does that Charlie Chaplin Walk!

There was a ‘new fox-trot song’ of the same title, a ‘Charlie Chaplin Glide’, ‘Charlie Chaplin – March Grotesque’, ‘Those Charlie Chaplin Feet’, ‘Charlie Chaplin, the Funniest of them All’, and ‘The Funniest Man in Pictures’, with words by Marguerite Kendall:

He tips his hat and twirls his cane,

His moustache drives the girls insane …

In France there was a popular ‘Charlot One-Step’.

By the autumn of 1915 Sydney had worked out his Keystone contract and now proposed to devote himself whole-time to the management of his brother’s affairs. He persuaded Chaplin that they should undertake the commercial exploitation of the various Chaplin by-products themselves, and accordingly the Charles Chaplin Music Company and the Charles Chaplin Advertising Service Company were incorporated. Neither seems to have lasted very long: the administrative costs and problems of chasing royalties on ephemeral productions selling for a few cents proved uneconomic. In October 1915 James Pershing, who had been appointed to run the Advertising Service, reported to Sydney:

We find that things pertaining to royalties are in a very chaotic state. There seems to be hundreds of people making different things under the name of Charlie Chaplin. First we have to find out where they are, what they are making, and are notifying them as fast as possible to stop or arrange with us for royalties, which is about all we can do.7

Sydney suggested that Aunt Kate would be an ideal English representative for the Advertising Service, and accordingly Mr Pershing wrote:

In regard to the English rights, we have attended to that by writing to your aunt, asking her to look us up an attorney and engage him on a commission basis, and are suggesting the various things that may be made over the name of Charlie and endeavouring to get her to place these rights herself, or have it done by some competent party. It is impossible for any of us to go over at the present time, although we realize that this should be done … 8

Evidently Aunt Kate entered into the arrangement with an enthusiasm worthy of her nephews, for a month later the President of the Advertising Service indignantly reported to Sydney:

Miss Kate Mowbray cabled that she had been appointed agent and insisted upon 25% royalties. We did not appoint her, as you know, and I hardly believed that you have assumed the authority. If you have, we are going to back you up, but we cannot, from our end, give her 25%. Let me hear from you in this connection so that we can write her intelligently.9

Almost from the moment of Chaplin’s arrival in the United States, there was a bizarre fascination with his racial origins. Even during the Karno tours, interviewers and reporters frequently reported that he was the child of Jewish vaudeville artists. Yet in the four generations that we can confidently trace back his ancestry – through the Chaplins, Hills, Terrys and Hodges, and certainly through the gypsy Smiths – there is no positive evidence of Jewish blood. All these forebears seem to have regularly performed the family rituals within the Church of England, until Hannah sought solace with the Baptists in later years.

Chaplin’s first recorded statement on the question dates from 1915, when a reporter asked him if, as was supposed, he was Jewish. With the grace he so often mustered in the face of the press, Chaplin replied, ‘I have not that good fortune.’ This was not an empty courtesy: throughout his life Chaplin would continue to express a profound admiration for the race (which in itself would certainly have led him to acknowledge any Jewish origins). On a boat returning from Europe in 1921 (see pages 304–5) he told a small girl who was a fellow passenger: ‘All great geniuses have Jewish blood in them. No, I am not Jewish … but I am sure there must be some somewhere in me. I hope so.’ This feeling for the race did not imply uncritical approval of everything Jewish. He was not circumcised himself and always suspected that circumcision must be dangerous psychologically in addition to being undesirable aesthetically and physically.10

A fragment of film in the Chaplin archive, showing Sydney and the studio staff seeing Chaplin off on an east-bound train, provides charming and curious evidence of his own conviction that he was not, to his regret, Jewish. The family tradition was that Sydney’s father, the putative Mr Hawkes, was Jewish – even though Sydney was baptized according to the rites of the Church of England. Fooling for the cameras, Chaplin puts his arm around Sydney and mimes, with beautiful clarity of expression, ‘We’re brothers. Aren’t we alike?’ He thereupon answers his own question in the negative, explaining the lack of familial resemblance by pointing a finger at Sydney and doing a stage-Jew impersonation, all shrugs and raised hands, to indicate that Sydney is Jewish and he is not. Another odd visual comment appears in a shot of Chaplin with Harry Lauder in 1918. Lauder draws a crude caricature of Chaplin on a blackboard. Chaplin pointedly alters the unmistakable hook nose of a caricature Jew.

Chaplin, the supposed Jew, was an early target for Nazi anti-Semitism. The Gold Rush was banned from the early years of the Third Reich, and Chaplin figured in a hideous publication11 attacking prominent international Jewish intellectuals. Along with Einstein, Reinhardt and others, Chaplin’s portrait, crudely retouched to emphasize its ‘Hebraic’ features, was printed with an accompanying caption which dismissed him as ‘a little Jewish acrobat, as disgusting as he is tedious’. Chaplin’s riposte, in The Great Dictator, was to play an overtly Jewish character, and to state, ‘I did this film for the Jews of the world.’ By this time he was adamant in his refusal ever to contradict any statement that he was a Jew. He explained to Ivor Montagu, ‘Anyone who denies this in respect of himself plays into the hands of the anti-Semites.’

Perhaps the most extraordinary and prescient tribute to Chaplin’s fame in his second year in pictures is an article contributed to the Chicago Little Review by a twenty-three-year-old essayist, the future playwright and screenwriter Ben Hecht:

He walks along carelessly, quietly, with an infinite philosophy! he walks with an indescribable step, shuffling along …

Charlie Chaplin is before them, Charles Chaplin with the wit of a vulgar buffoon and the soul of a world artist. He walks, he stumbles, he dances, he falls. His inimitable gyrations release torrents of mirth, clean as spring freshets. He is cruel. He is absurd; unmanly; tawdry; cheap; artificial. And yet behind his crudities, his obscenities, his inartistic and outrageous contortions his ‘divinity’ shines. He is the Mob God. He is a child and a clown. He is a gutter snipe and an artist. He is the incarnation of the latent, imperfect and childlike genius that lies buried under the fiberless flesh of his worshippers. They have created him in their image. He is the Mob on two legs. They love him and laugh.

‘Fruits to Om.’

‘Glory to Zeus.’

‘Mercy, Jesus.’

‘Praised be Allah.’

‘Hats off to Charlie Chaplin.’