7

Penalties and Rewards of Independence

The Adventurer, released on 22 October 1917, concluded the contract with Mutual. Unlike the Essanay relationship, it ended amicably on both sides: the company had sagely remained patient through the increasingly lengthy delays between releases. In fact Mutual offered a million dollars for eight more films, but Chaplin realized that he needed still greater independence if he was to achieve the standards of which he knew he was capable. Sydney was again sent off shopping for a new contract. On the way to New York in April 1917 he stopped off in Chicago and spoke to the press:

All the big film companies are now negotiating with me for Charlie’s services, and I am just waiting for the best offer. We are in no hurry but I hope to be able to sign him up before leaving New York this time.

The best offer we have had so far is $1,000,000 for eight pictures. We are also considering forming our own producing company, but haven’t been able to arrange satisfactory releasing arrangements, so probably will not enter the field as producers for several months.

There is one thing that will be stipulated in the articles of all Charlie Chaplin contracts hereafter, and that is that Charlie be allowed all the time he needs and all the money for producing them the way he wants. No more of this sixty-mile-an-hour producing stuff will be seen in the Chaplin films from now on. Charlie has made enough money now so that he doesn’t have to worry. He is able to either dictate his own terms or sit back and bide his time.

Hereafter the Chaplin pictures will take from two to three times longer to produce than they do now. The settings and stage properties will be the finest. It is quality, not quantity that we are after. After we have made a scene and it isn’t up to the new Chaplin quality, it will be made over. And then, if the whole reel doesn’t satisfy Charlie, it will not be released, no matter what money is offered, but thrown into the discard where it belongs.

A close observer of late probably has noticed the increased quality of Chaplin pictures. Charlie has been bringing out more and more new stuff, and he has a great deal more to bring out. The new pictures will be surprises even for the most ardent Chaplin fans.

Also the films hereafter, instead of being just a series of comical stunts or humorous situations, will have a continuous story running through them, with a beginning gradually rising to a climax and winding up with the catastrophe.

We are in the field now for real scenarios. We want the best, and are now negotiating with some of the finest writers in the country to prepare them for us. We have the money to buy what we want, and will be most discriminating in selecting from what is offered.

The next Chaplin series will be wonders. They will be improved upon in every way from those that have gone before. The supporting casts will be greatly strengthened.

Either in this next series, or in those that we plan producing ourselves, I myself will play with Charlie. I have a great many things that are new and will go big, and the two of us, with a strong supporting cast, good stories and good directing and scenery, will be unbeatable.

Charlie and I talked it over before I left Los Angeles on this trip, and we concluded that it was up to us to make the name Chaplin stand for all that there is in true and wholesome comedy, no matter what some of the producing companies want. That is why I am going to take plenty of time before signing the next contract.1

Strategically, Sydney could not have chosen a better moment to go to New York. The film industry was on the point of a revolution, and Chaplin was to be a significant player in it. The most influential figure in industry politics was, and was long to remain, Adolph Zukor. Zukor had arrived in the United States as an immigrant the year before Chaplin was born. He had gone into the fur trade, made a killing by inventing a patent clip for fox furs, and then early in the century entered the nickelodeon business. In 1973, on his hundredth birthday, he was still around to pass judgement on the movies: ‘There is nothing wrong with Hollywood that good pictures will not cure.’

Zukor was the first to perceive that the key to domination of the film industry lay with the stars. Having captured the unchallenged sweetheart of the box office, Mary Pickford, by the beginning of 1917, Zukor’s Paramount Pictures Corporation was on the way to achieving a monopoly of the nation’s first-run theatrical outlets. This would enable him to raise his rental rates without restraint. A group of prominent exhibitors, led by Thomas L. Tally and John D. Williams, decided to fight Zukor by creating an organization to buy, or make, and distribute pictures of its own. The new organization, First National Exhibitors’ Circuit, had its inaugural meeting in April 1917. The timing was perfect. Nothing could have given First National a finer send-off than the announcement two months later that they had captured Chaplin and that their arrangement with him was of a kind likely to be much more attractive to other stars than any which Zukor’s Paramount-Artcraft could offer.

Chaplin was to become his own producer, contracted to make for First National eight two-reel comedies a year. First National would advance $125,000 to produce each negative, with the star’s salary included in the sum. If the films were longer than two reels, First National would advance $15,000 for each additional reel. The company was also to pay for positives, trade advertising and various other incidentals. The cost of distribution was set at 30 per cent of the total rentals, and after all costs were recouped, First National and Chaplin were to divide net profits equally.

The contract involved protracted negotiations between First National and Sydney, aided by Charlie’s lawyer, Nathan Burkan, and was completed late in June 1917. Sydney’s doggedness in fighting for Charlie’s advantage at this time was the more remarkable since he was having troubles of his own. His wife Minnie had undergone a dangerous operation in Sterns Hospital in New York: in the second month of pregnancy a growth was discovered in her stomach and its removal involved the loss of the child. She was told that she would be able to have future pregnancies, but in fact the couple were to remain childless. Moreover, Sydney was fighting to gain for Charlie an independence which privately made him nervous. Whatever he might say to the press about his brother’s perfectionism, as long as they worked together he would be uneasy at Charlie’s disregard for cost in his single-minded pursuit of quality.

On 3 July Sydney wrote:

Well Charlie, I hope you were satisfied with the contract. Burkan and I tried to think of every little thing we could to put in, and I think everything of importance has been covered. During the discussion of the terms of the contract, the subject of a second negative came up. The other side were of opinion that you should include a second negative for the sum arranged as only a limited number of prints could be obtained from the one negative, besides the risk of losing some in the event it would be necessary to ship it abroad. I tried to evade the provision of a second negative, but as they had been very lenient with all our other clauses in the contract and had raised very few objections I did not wish to appear too grabbing, so offered to provide a second negative if they would pay half the cost which they agreed to. I told them the cost of film and cameraman would be about $1000 per picture, but I very much doubt whether it will cost so much as that. Anyway they agreed to pay an extra $500 a picture, so under the circumstances, if you will take my advice, you will use three cameras on your pictures in the future. I certainly think it is worth the added cost to have a brand new negative locked away for the future, especially as the rights to the pictures revert to you after five years, and I feel sure they have a great future value.

There was one other point that was discussed strongly during the framing of the contract, and that was that instead of them paying you the $200,000 in advance, the money should be deposited in escrow until you had carried out your contract. Even Burkan agreed with them in this but I stood pat and insisted that the cash should be paid without any restrictions. I had mother’s old saying well in mind, that ‘possession is nine points of the law’ so they eventually agreed after a long discussion. How did you like the clause about the extra reel? Getting that by pleased me more than anything. I was racking my brains all the way up in the train trying to think how I could raise the price of your pictures even more than I had agreed upon, and yet not break my word with them, when the thought occurred to me, why not make them pay for extra footage. I remembered how difficult it was for you to cut your picture down to footage, and how in doing so you were often compelled to sacrifice a lot of good business and sometimes whole factions.2 Here was a chance to not only get them to accept a picture if by chance it should run over two thousand feet, but at the same time make them pay for it. Of course I did not tell them that you had great difficulty in cutting your pictures to two thousand feet. On the contrary I said that many a time you had a story that would make an excellent three-reel picture, but you were compelled to make it a mediocre two reeler, due to the restrictions of your past contracts, but I also impressed them strongly with the fact that by making a three reeler, it would naturally take a great deal more money and time, so with that I raised the price another fifteen thousand dollars per picture which should pay for the cost of your production, and if you are wise, every picture will run about 2500 feet.

Well Charlie, everyone in town here seems to be remarking about the much better class work you are turning out now. I am glad to hear it and I hope you will keep it up and above all refrain from any vulgarity. We must try and frame up a bunch of good stories for the next year and above all, decide and know exactly what you are going to do before the sets are ordered. Have you decided where you are going for your holiday? Marcus Loew I think would be glad to take a trip with you somewhere … 3

There is a hint of reproach in Sydney’s remark about Charlie’s need to make up his mind what he is going to do before building his sets, and an optimism that was quickly to be dashed in his hope that the films could be made at a cost within the supplementary advance for an extra reel. Though he never adopted Sydney’s wily but somewhat impractical advice about shooting with three cameras, Charlie profited by First National’s demand that he make two negatives. Throughout the rest of his career in silent films he always shot with two cameras. The wisdom of this precaution was proved when the second negative of The Kid was accidentally destroyed by fire in the late summer of 1938.

Marcus Loew did not have the pleasure of taking a trip with Chaplin. Having finished The Adventurer Charlie took off for Hawaii accompanied by Edna, his secretary-valet Tom Harrington, and Rob Wagner, who had become a regular member of the immediate entourage. A teacher of Greek and art, Wagner became fascinated by Chaplin and had hoped to use this trip to embark on a biography. Instead he worked for a period as press representative and wrote a number of very perceptive articles on Chaplin’s screen persona.

The party left in August and stayed five weeks. The affair with Edna seemed already to have ended, but perhaps there was some forlorn hope on one side or the other that the holiday might revive it. Chaplin, though, was eager to get back. Before he left he had approved plans for his new studio and was impatient to start construction. The site was a five-acre plot which had been the home of a Mr R. S. McClennan, on the corner of Sunset Boulevard and La Brea Avenue. At the north side of the property stood a handsome ten-roomed house in colonial style, which initially Chaplin thought of using as his own residence. Instead, Sydney and Minnie lived there for a time. The site was then a good mile away from the usual studio quarter, in one of Hollywood’s best residential districts; at first there was considerable local alarm at this encroachment by the movie folk. Film studios of that period tended to be no asset to a community: mostly they were dreadful agglomerations of tumble-down outhouses, corrugated iron, flapping canvas diffusers supported on crazy structures of girders, the whole protected by flimsy timber fences. Chaplin’s Lone Star Studio had been one of the more presentable examples.

However, Chaplin’s plans completely won over the elite of La Brea and De Longpre Avenues. The exposed elevations were designed to look like a row of English cottages. The local aesthetes were bound to admit that the irruption of an Olde English village street on Sunset ‘was not only conferring distinction on the neighborhood, but was considerably improving it’. The cottages served as offices, dressing rooms and work rooms, and the elevation that faced into the studio was more functionally designed in the style of Californian bungalows. The grounds were laid out with lawns and gardens, and there was a large swimming pool. The production facilities were the best that money could buy.

The stage will be unusually large, and for months Mr Chaplin has been studying a new diffusing system which will dispense with the old coverings and at the same time will cope with all the climatic conditions of the Pacific coast.

The site of the new studio was purchased for the sum of $30,500,4 but Mr Chaplin plans the investment of $500,000 in beautifying his property.

Charlie and Sydney broke the first sod in November, with an informal and unpublicized ceremony witnessed by the permanent cast and unit. During the three months it took to build the studio Rollie Totheroh filmed its progress. His shots of the daily growth of the cottage façades, when cut together as stop-action, provided an amusing effect of a magical mushroom growth. When everything was more or less ready, Chaplin shot more film to show off the facilities of the studio. He was filmed arriving in his car and going to his dressing room to get into his costume and make-up. Tom Harrington is seen solemnly opening a safe and taking out the studio’s ‘most priceless possessions’, Charlie’s derby and boots, and then being reprimanded for failing to treat them with the proper reverence. The dreadful boots are then delicately placed on a cushion. On the stage (at this time almost bare of sets or scenery) the company, including Henry Bergman, Albert Austin and the diminutive Loyal Underwood, hide their playing cards and take up suitably industrious attitudes. Chaplin supervises a rehearsal, and delicately and repeatedly instructs a gigantic actor how to strangle Loyal Underwood. Other scenes show Chaplin attending to the hairdressing of an actress, and fun and games at the pool.

At some point during the First National contract Chaplin seems to have had the idea of putting this material together as a two-reeler to be called How To Make Movies, but perhaps First National would not accept it as a substitute for regular comedy. Parts of the material were used by Chaplin as an introduction to a later reissue of a compilation of First National films, The Chaplin Revue. In 1982, Kevin Brownlow and David Gill edited the whole film together, using the continuity indicated by a surviving title list.

In January 1918, Alf Reeves arrived from England to join the studio staff. Since the start of the war he had been touring Britain with the Karno companies, ‘thrashing the old horse Mumming Birds to pieces still’. He had kept up a fairly regular correspondence with the Chaplin brothers, giving them news of Karno and all their old colleagues, and reporting on the reception of Chaplin’s new fame. In January 1916 he wrote to Chaplin, ‘I always, as you know, expected big things of you, but never dreamed of the extent of the popularity you would enjoy.’ In August 1917, he congratulated the brothers on Charlie’s new contract: ‘Everyone’s breath is taken away.’

Alf’s health had not been good, and he had nostalgic memories of California:

I have to be careful, and these winters here are rather trying – you know the old digs – sitting room just warm as long as you keep around the fires – cold when you leave them, and as for the bedrooms – wow. I really miss the good old steam heat in those nice hotel rooms there, where the warmth is equable and distributed all over the house … The little hotel room with its bath, its running water, its elevator, and up to date comfort of it springs to my memory …

When Sydney suggested that there might be a job for him at the new studios Alf leapt at the chance:

When you tell me there is a probability of Charlie embarking on his own account next year, and that he might think of a way to fix me up you fill me full of good hopes. There is nothing I should like more than a long sojourn in the land of Sun. Warm weather and I agree. Venice, Los Angeles, is one of my ideal spots on this earth. Your suggestion, even, of the bungalow, with its car ride to town, is far too good to be true I am afraid – especially the Automobile part of it, but then, say I, what’s the matter with the streetcar …?

So when you are again conversing with Charlie, and thoughts turn this far – if there is anything to suit me – you know about the extent of my humble qualifications – here we are all ready and willing – two of us. Amy is a good cook – Charlie knows – ask him … We used to indulge in beefsteak and kidney puddings, and used to do some scoffing … There are no bones in a beefsteak and kidney pudding. If there had been – I’m sure we would have eaten them. It was Charlie’s favourite dinner.

At the end of August 1917 Chaplin offered Reeves a job at the studio, and he at once handed his resignation to Karno and set about making arrangements for sailing. Even though he was forty-eight and so too old for military service, there was some difficulty in obtaining the necessary visas from the Foreign Office. But at last, just after Christmas 1917, Alf and Amy set sail. Apart from his managerial duties, Alf was to make brief acting appearances in A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms.

When the studio was completed Chaplin decided that it would be good for public relations to open it up to the public, and 2000 people signed the visitors’ book in January 1918. A disagreeable incident which resulted from this undoubtedly contributed to Chaplin’s secrecy and suspicion in later years. Two people who had represented themselves as journalists spent three days in the studio before they were detected eavesdropping outside a production meeting. When they were searched they were found to be in possession of a series of eight sketches of the completed sets for A Dog’s Life, stenograph notes of story discussions, and descriptions of characters and costumes. In view of the extent to which Chaplin’s films were improvised and altered until the very last day of production, his claim that it had cost an estimated $10,000 to scrap the material already planned must be regarded as exaggeration. However, the incident was taken seriously enough for all visitors to be banned for the future.

Everything was ready for shooting to start on 15 January 1918. The first production was provisionally titled I Should Worry; only when it was completed did Chaplin decide on an alternative title, A Dog’s Life. It remains one of his most perfect films. The great pioneer French critic Louis Delluc (1890–1924) called it ‘the cinema’s first total work of art’. It is as fast-paced and prodigal of gags as a Karno sketch; its individual scenes cohere into a purposeful structure; at the same time it has a harder core of reality than any film that Chaplin had made before. It is about street life, low life, poverty and hunger, prostitution and exploitation. Without pretension and without sacrificing anything of its comic verve, Chaplin drives home the parallel between the existence of a stray dog, Scraps, and two human unfortunates – Charlie the Tramp and Edna, the bar singer. A Dog’s Life, said Photoplay ‘though only a grimy little backyard tableau, ranks with the year’s few real achievements’.

Charlie the Tramp’s battle with other applicants for the few available jobs at the Employment Office is compared with Scraps’s furious struggle over a bone with a horde of bigger and fiercer dogs. The two strays adopt each other and prove an effective partnership in filching a meal from Syd Chaplin’s lunch-wagon. They chance into the Green Dragon, described by a critic of the day as ‘a dance hall of the character for which Coney Island, New York’s Bowery and the Tenderloin of Chicago were famous some twenty years ago, where the “celebrities” of the underworld gave and took fractured skulls as nightly souvenirs’. It is there that they meet Edna, and become rich by outwitting a couple of crooks who have stolen the wallet of a passing drunk.

A Dog’s Life has a strange and charming little coda. The last image of Charlie’s escape from the crooks ends on an iris-in. This is followed by an iris-out on a vast ploughed field. Charlie, in a big straw hat, astride a ridge between the furrows, waddles along, dibbing holes with his fore-finger and planting a seed in each. He looks up and waves happily towards the camera and to Edna, awaiting him in their idyllic little cottage, all cretonne and ‘Home Sweet Home’. A cradle stands beside the fire and the couple gaze into it with pride. The audience is permitted to jump to the obvious conclusion before the interior of the cradle is revealed: here lies a proud Scraps amongst a litter of puppies. The pride is not unjustified – in earlier scenes Scraps’s maleness has been more than evident.

Charlie had perceived the comic possibilities of dogs at least as early as The Champion – and Sydney, as we have seen, had introduced canine comedy into Karno’s Flats sketch years earlier. More than a year before he began A Dog’s Life, in December 1916, the newspapers were carrying the headline ‘Chaplin Wants A Dog with Lots of Comedy Sense’. Chaplin told the reporters:

For a long time I’ve been considering the idea that a good comedy dog would be an asset in some of my plays, and of course the first that was offered me was a dachshund. The long snaky piece of hose got on my nerves. I bought him from a fat man named Ehrmentraut, and when Sausages went back to his master I made no kick.

The second was a Pomeranian picked up by Miss Purviance, who had him clipped where he ought to have worn hair and left him with whiskers where he didn’t need ’em. I got sick of having ‘Fluffy Ruffles’ round me so I traded the ‘Pom’ for Helene Rosson’s poodle. That moon-eyed snuffling little beast lasted two days.

After this he was reported to have tried a Boston bull terrier, and in March 1917 he was said to have been seen in the company of a pedigree English bulldog called Bandy, whose grandmother, appropriately, was Brixton Bess. ‘What I really want,’ he said, ‘is a mongrel dog. The funniest “purps” I ever set eyes on were mongrels. These studio beasts are too well kept. What I want is a dog that can appreciate a bone and is hungry enough to be funny for his feed. I’m watching all the alleys and some day I’ll come home with a comedy dog that will fill the bill.’ If the news reports are to be believed, after starting work on A Dog’s Life Chaplin had taken into the studio twenty-one dogs from the Los Angeles pound. In response to complaints from the neighbours, however, the city authorities insisted that he reduce the number to twelve. The studio petty cash accounts show entries for dogs’ meat starting from the second week of production and continuing until the end of shooting. The eventual star of the film, a charming little mongrel called Mut (or Mutt), became resident and remained on the staff until his untimely death.

Even at this critical early period of his career as an independent, Chaplin was apparently always ready for extemporization or distraction. He had to be, for his studio was to become a place of pilgrimage for the famous in all walks of life who chanced to be in Los Angeles. Harry Lauder (1870–1950), the great Scottish comedian who had rocketed to stardom in the British music hall about the time that Chaplin was touring with the Eight Lancashire Lads, was playing the Empress Theatre. He came to call on 22 January 1918. All work stopped while the two comedians fraternized. Over lunch they decided to make a short film together, there and then, in aid of the Million Pound War Fund to which Lauder had dedicated his efforts following the death of his son at the front in December 1916.5

In the afternoon the two cameras were set up and 745 feet of film (approximately twelve and a half minutes) were shot while the two comedians fooled around. Lauder put on Chaplin’s derby and twirled his cane, while Chaplin adopted Lauder’s tam-o’-shanter and knobbly walking stick; each impersonated the other’s characteristic comedy walk – Chaplin a good deal more successfully than Lauder. There was more business with a bottle of whisky and a blackboard on which they drew caricatures of each other. The pièce de résistance was the old music hall ‘William Tell’ gag. Chaplin placed an apple on Lauder’s head and then prepared to shoot it with a pistol. Each time Chaplin’s back was turned, however, Lauder would take a great bite out of the apple, reducing it to an emaciated core before Chaplin had a chance to take aim. Each time Chaplin turned to throw a suspicious glance, Lauder’s face would freeze into blank, immobile innocence. The two comedians optimistically told the press that they anticipated the film would raise a million dollars for the fund. They were disappointed: it is not certain whether the public even saw the film, if, indeed, it was finished.

The T-shaped street set first seen in Easy Street, which, variously re-dressed to suit the current needs, was to remain for twenty years the central and essential location for Chaplin’s comic world, was erected in the new studio. In A Dog’s Life Chaplin fixes on this little plot of ground all the mean streets of every city in the world. Methley Street and all the other back ways of Kennington which he had wandered as a boy are clearly the inspiration, just as they were for Easy Street. Yet Chaplin discovers here something universal, in the mysterious doorways, the loitering bums, the loungers at corners, the sitters on doorsteps, the traders with their flimsy stalls only waiting for pilferers or for inevitable catastrophe which will upend them with avalanches of fruit and vegetables. The locale and atmosphere were to prove as recognizable to audiences in London as in Paris, Chicago, Rio or Manila. Yet it is not an abstraction: there is such a local reality in the setting that Chaplin was able to cut from studio shots to scenes filmed on location in the city (there was a day’s shooting of dog scenes in front of the Palace Market) without the difference being evident.

Little pre-planning was possible with the dog scenes. The animals and Charlie set off on the run, and Rollie Totheroh and Jack Wilson, the resourceful cameramen, followed them as best they could. The canine extras were fearsome brutes, and things evidently became somewhat boisterous. After one or two days of work with the dogs, the studio prop people sent out for a large syringe and sixty-five cents’ worth of ammonia to separate the dogs when they became too rough.

After a couple of weeks Chaplin suddenly became dissatisfied with the entire story. His staff had become too accustomed to these abrupt switches of mood to be unduly disconcerted by them. Returning to the studio on Monday morning, 11 February, he announced that they would start on an entirely new film to be called Wiggle and Son. He took a few shots and ordered the property department to buy ant paste, salts and half a dozen snails, for comic purposes which will never now be divined. The next day, however, Wiggle and Son was forgotten, and Chaplin returned with fresh enthusiasm to I Should Worry, as the film was still officially known. (A report in the Scottish supplement of The Bioscope claims that the final title was suggested by a remark of Harry Lauder’s, who told Chaplin, ‘It’s a dog’s life you’re leadin’ these days, Charlie.’)

For the crowd scenes in the dance hall, thirty extras were hired to supplement the stock company and, as usually happened on Chaplin productions, friends and studio staff were recruited from time to time. Alf Reeves and Rob Wagner may be glimpsed, and Sydney’s wife, Minnie Chaplin, played a role. The tough proprietor of the dance hall was played by another new acquaintance of Chaplin’s, Granville Redmond, a successful landscape painter. Redmond was a deaf-mute, but he and his director established a perfect pantomime communication, as his performances in A Dog’s Life and The Kid testify.

Grace Kingsley, a keenly observant journalist of the day, visited the studio during the filming of the dance hall sequence, and recorded her impressions:

It’s coming to be quite the fad to visit the Chaplin Studio – that is, if you can get in. Of course nobody is allowed to visit there. Nobody, that is, except picture magnates and newspaper and magazine representatives and their friends, and fellow artists – of whom there are always some thousands in the city – and all the soldiers and sailors and –

But that’s enough to show you what one of Charlie’s days must be like. And he’s the most astonishing combination of busy artist and gracious, good-natured host …

Catch Charlie in the right mood and he’ll do $10,000 worth of acting for you while you wait. So that, though following Charlie Chaplin around all day is as strenuous as following a soldier at drill, the similarity ends there.

After Charlie has drawn on his funny trousers and shoes and his old shirt, in the privacy of his luxurious dressing room, he finishes making up at a little dressing table on the stage, where he can keep an eye on the dressing of the sets. This happens around 9 o’clock, when the sun encourages photography.

‘If I don’t get this moustache on right, it’s all off,’ grinned Charlie as he carefully combed the crepe and cut it, pasting it on his lip first as a big wad. ‘Got to trim that down, or Chester Conklin will think I’m trying to steal his stuff!’

I’m only one of the many interviewers who call on Charlie, so he talks as he makes up: ‘The day of sausage pictures is over,’ he said. Then he made an important announcement. ‘I shall never again bind myself to the making of two-reel comedies. You must have a story, and it’s got to be a clear story. Otherwise quite naturally the public doesn’t get it. Also you’ve got to have the gags and the jokes and the jazz. You’ve got to grab these out of the air as it were. You don’t know just when or where the ideas come from – and sometimes they don’t!’

Charlie’s make-up being on straight by now and his hat on crooked, he took a peep in his glass and descrying over his shoulders a bunch of soldiers, of course, he had to go over and say ‘Hello’. Some dear ladies of the Red Cross just then entered, and a candy company having contributed a whole shop full of chocolates for Charlie to auction off, he had to pause to be photographed before the collection with some of the Red Cross ladies.

I think Charlie gets most of his inspiration when he is ‘kidding’. He wanted some special idea for that photograph, and he took a dozen different comical poses before, grasping a broom which lay on the set, he hit upon the right idea.

‘The Chocolate Soldier!’ he grinned, as he fell into a funny attitude with the broom as a gun. Then the comedian went over to the dance hall set and called out to Miss Purviance and the other members of the company. He sat down beside the two cameras that are always ranged on the action, and he shut his eyes and put his fingers in his ears.

‘That’s the way he visualizes an idea,’ explained Brother Sid. ‘He sees it on the screen that way.’

A rehearsal – a long and careful rehearsal with Chaplin playing all the parts in turn – followed …

It was lunch time then. So we all went to lunch in Sid’s beautiful house, Charlie and Edna Purviance still in their make-up. After lunch it was discovered that there was one of those awful – what Charlie calls ‘brick walls’ – a dead stop, until a minor snarl in the story and its action was straightened out. For this, Charlie called Charles Lapworth into consultation. Then out came Charlie and kidded around a bit – he does that while he’s waiting for an idea to pop, kept everyone laughing, while in the back of his head all the while was that awful question – the brick wall. Presently it came, the longed-for idea.

He had just started once more for the stage when Carlyle Robinson, his publicity man, came forward, announcing in a fairly awe-struck whisper: ‘The Earl of Dunmore!’

Of course one cannot overlook a real Earl on the busiest day, so Mr Chaplin paused and chatted a few moments. And though the Earl was an Earl, he realized that a comedian is a hard-working person, and so insisted Charlie should go back to work. Anyhow, Earl or no Earl he was probably dying, just like everybody else, to see Charlie at work. So Charlie hopped onto the stage, and, having at last got possession of the longed-for idea, and having escaped all visitors, he set briskly to work. Half an hour, an hour, two hours passed, with no let-up to the filming of scenes. Somebody brought him some mail, which, after opening, he dropped as carelessly as the hero of a motion picture does when thickening the plot with ‘the papers’.

‘He’ll be working like this until he finishes all the scenes he has in mind,’ said Brother Sid, ‘until 6, 7, or even 8 o’clock. And when the cutting begins, he will work all night and all day too.’

You’d think to see him acting out there on the stage, that he was still kidding. Maybe he doesn’t quite know himself, you think.6

Charles Lapworth was an émigré English journalist who had arrived to interview Chaplin, and briefly found a niche in the studio. His own impressions of Chaplin in his dressing room and on the set fill out Grace Kingsley’s description:

He will permit you to sit in his dressing room, and let you do the talking while he affixes the horsehair to make up his moustache. You will notice a violin near at hand, also a cello. And it will be unusual if Charlie does not pick up the fiddle and the bow, and accompany your remarks with an obbligato from the classics, what time he will fix you with a far-away stare and keep you going with monosyllabic responses.

If you run out of remarks before the violinist has come back to earth, and you are curious enough to glance round the luxuriously furnished room, you may judge a little of Charlie’s literary tastes by observing cheek by jowl with Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights, Sigmund Freud’s Psychoneurosis and Lafcadio Hearn’s Life and Literature; not on the shelves, but lying around as if they are really being read. On the desk, perhaps, Mark Twain’s Mysterious Stranger, an allegory that sometimes Charlie will get enthusiastic about; while in the bookcase one may notice that the man who first introduced custard pie into polite argument has not failed to acquaint himself with what the philosophers from way back down to Bergson have had to say about the underlying causes of laughter …

No matter how competent any member of his company may be, he has to acknowledge that when he responds to Charlie’s direction he achieves better results. It is interesting, for instance, to watch him show the big heavy how to be ‘tough’, or a girl, obviously at the moral crossroads, how to look the part. His variety of facial gestures is amazing: he is a king of burlesque.

Sometimes, of course, he strikes a snag, and then he will just disappear off the ‘lot’. The whole works are at a standstill, and there is a hue and cry around the neighboring orange groves. Perhaps two hours afterwards the comedian steals back to the studio, and his return is made known by the soul-stirring strains from his cello. A little later work is resumed, and Charlie will confess that after much prayerful wrestling he has ironed out the kinks …

He frequently interrupts the ‘shooting’ with an impromptu clog dance. He may close his eyes, and with his hands make weird passes of a geometrical character. But nobody gets alarmed. The chief is just inwardly visualizing the camera shots and when he has got the angles worked out to his own satisfaction he gives instructions for the necessary modifications of the set. Like as not he will order it burned; he has changed his mind, and the carpenters have to tear down an elaborate and costly set, unused.

Chaplin is at once the joy and despair of all managers. If he does not feel like work, he won’t work. And he can always fall back on the public for support of his argument that the public are entitled to the best. If he does not feel he is doing his best, he quits and hang the expense. And the thousands of feet of film that he shoots go to waste. Again, that’s nobody’s business but his. He pays for it, and he will declare that if a picture costs him every penny he makes (it took him three months to make his last one), he is still determined to make it as perfect as he can. And, oh the travail of the cutting! Sometimes sixty thousand feet to get two thousand. Only a rewrite man on a newspaper knows what such a boiling down means. Yet Charlie, and Charlie alone, does the cutting. And he ruthlessly condemns to the scrap-heap miles of excellent comedy that would make the fortunes of other comedians.7

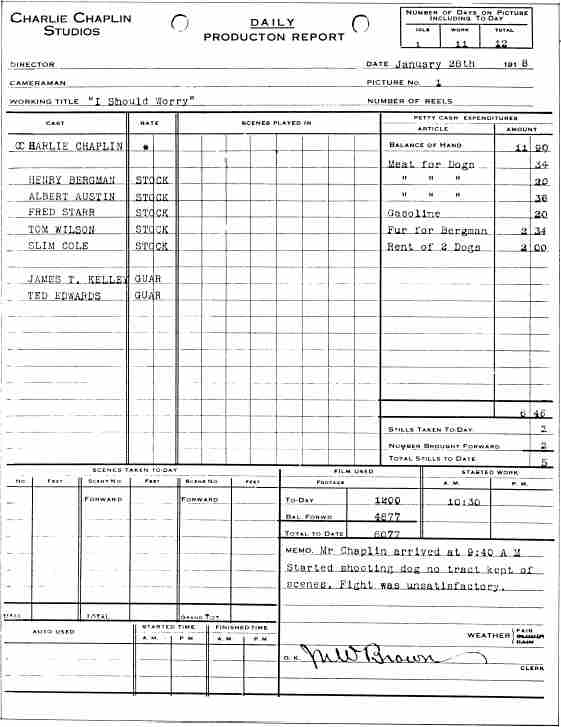

For all Chaplin’s extravagance in the pursuit of perfection, the bookkeeping of this first independent production was meticulous; and the daily record of petty cash disbursements is often as amusing as revealing. Everything is detailed, down to the last five cents for ‘beans’, seemingly used by Charlie to represent seeds in the final sequence. A wastage of thirty-five feet of film stock (with a running time of about thirty seconds) calls for detailed explanation in the accounts. There are daily entries for dog meat and for gas and oil for the studio Ford (at nineteen cents a gallon). Prop food and drink – pies, sausages, rolls, ‘tamalies’, chewing gum, beer, near-beer and ginger-ale – also figure large. Henry Bergman played several roles in the film, but his favourite was clearly that of the stout, gum-chewing old lady in the dance hall, whose tears on hearing Edna’s plaintive song drench Charlie. Entries for ‘fur for Bergman – $2.34’ and ‘elastic for Bergman – 30¢’ show that Henry started preparing his costume well ahead of time. On 26 February there is a disconcerting item: ‘Whiskey (Mut) – 60¢’. The explanation is a scene in which Charlie and the dog sleep together on their plot of waste ground. Charlie uses the suspiciously compliant animal as a pillow, energetically plumping him into shape before settling down, and then agitatedly searching the immobile dog for fleas. (‘There are strangers in our midst,’ says one of the film’s few sub-titles.) The item in the petty cash account reveals the secret of Mut’s docility: he was dead drunk.

Shooting was completed on 22 March, when Chaplin used 1792 feet of film to round off 1000 takes and 351,887 feet of film exposed on each of the two cameras. This time Chaplin was forced to accept help with the editing. From 26 to 29 March he stayed night and day in the cutting room with Bergman, the two cameramen and two assistants, Brown and Depew, to help him. Between times he had a last-minute inspiration and shot a charming little scene in which Charlie sits on the steps of a second-hand store and feeds the dog with milk from a near-empty bottle he has found there. When the dog cannot reach the milk with his tongue, Charlie obligingly dips Mut’s tail into the bottle and gives it to him to suck like a pacifier.

With a superhuman effort the cutting was completed late on 31 March, and Chaplin was ready to depart on a Liberty Bond tour the following day. The staff worked on to prepare the negatives. While Chaplin was off on the Bond tour, the staff were instructed to prepare ideas for submission on his return. Mut, sad to say, did not live to see Charlie’s return to California. He had apparently grown so attached to his master that he pined during his absence, refused to eat, and died. He was buried in the studio ground under a little memorial composed of artistically arranged garbage, and with the epitaph: ‘Mut, died April 29th – a broken heart’. His single film role had earned him his small piece of immortality.

The trip east was made in company with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Rob Wagner. The plan was for the three stars to take part in the official launching of the Third Liberty Bond campaign in Washington, to go on together to New York, and then to split up, Doug and Mary taking on the northern states and Chaplin the southern. Chaplin slept during the first two days of the rail journey. Recovering from his exhaustion, he set to writing his speech and confided to the others his nervousness about making a serious address to a crowd. Doug suggested that he practise on the crowd that gathered around the train at a stop en route but, as the last speaker, he found the train moving off just as he got into his stride, enthusiastically addressing a rapidly receding audience.

In Washington, the party made a triumphal progress through the streets to a football field where a vast crowd had come to hear them. Marie Dressler was on the platform as well, and when Chaplin was carried away by his own eloquence and fell off the platform, he managed to take the ample Marie with him. They fell on top of the young Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Later they were formally presented to President Wilson at the White House. Chaplin felt that he and the President were mutually unimpressed by the encounter.

In New York the excitement was even greater. Crowds began to gather at the junction of Broad and Wall Streets during the morning, and by the time the party arrived around noon on 8 April 1918, it was estimated that between twenty and thirty thousand people were waiting, many clinging to the sides of the Morgan Building and the Stock Exchange and the pillars of the Sub-Treasury. Their speeches were greeted with applause, laughter and shouting; and the crowd went wild when Fairbanks lifted Chaplin onto his shoulders.

Chaplin was wearing a wasp-waisted blue suit, light-top shoes and a black derby. ‘Now listen –’ he began, only to be interrupted by cheers and laughter from the thousands of bankers, brokers, office boys and stenographers. ‘I never made a speech before in my life –’ he continued, and was interrupted again, ‘– but I believe I can make one now!’ The next few words were inaudible, then the crowd settled down, and most of the rest of his words, screamed through a megaphone, were heard:

You people out there – I want you to forget all about percentages in this third Liberty Loan. Human life is at stake, and no one ought to worry about what rate of interest the bonds are going to bring or what he can make by purchasing them.

Money is needed – money to support the great army and navy of Uncle Sam. This very minute the Germans occupy a position of advantage, and we have got to get the dollars. It ought to go over so that we can drive that old devil, the Kaiser, out of France!8

The cheers for this sentiment resounded through several blocks of the city. When the crowd were eventually quiet, Chaplin concluded: ‘How many of you men – how many of you boys, out there, have bought or are willing to buy Liberty Bonds?’ The hand-stretching that followed, said the Wall Street Journal, ‘suggested vividly the latter part of the seventh innings at the Polo Grounds during a World Series.’

The New York trip brought one personal bonus. Marie Doro, the beautiful star of the London production of Sherlock Holmes thirteen years before, was playing in Barbara at the Klaw Theatre, and Chaplin was able to arrange an intimate dinner with her. The impossible dream of the sixteen-year-old who had played Billy the pageboy had come true.

Chaplin’s tour began at Petersburg, Virginia, and took him through North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi. He arrived in New Orleans exhausted and was forced to rest for a few days before completing the tour, and returned home via Texas. In Memphis he found waiting for him a letter from his exasperated studio manager, John Jasper, resigning his post. Chaplin had departed California leaving Jasper’s drawing account for running the studio three weeks in arrears. In reply to Jasper’s protests, he had arranged by cable for a weekly payment of $2000, even though it was previously agreed that the minimum average budget was $3000. ‘I expected of course that I would have the money every week,’ wrote Jasper. ‘The only way any Manager can ever give satisfaction in this job is to have a drawing account. Why don’t you put sufficient funds in the Citizen’s National Bank and stop all this confusion? It is not as if you did not have the money like so many others.’

Chaplin appears not to have been gravely inconvenienced by the departure of Jasper. Alf Reeves was immediately appointed as his successor, and for the next twenty-eight years proved an ideal manager, seemingly never surprised or discomposed by his employer’s caprices.

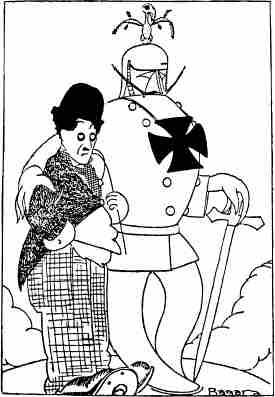

Chaplin was back in Hollywood in early May and by the end of the month was ready to start his new film, tentatively recorded as ‘Production No 2. Camouflage. 2 reels’, but eventually to be called Shoulder Arms. The notion of Charlie at war was irresistible. From the time of the ‘slacker’ campaign against him, newspaper cartoonists in every country had delighted in speculating on the possibilities of a confrontation between Charlie and the Kaiser. Late in 1917, Chaplin had amused himself by drawing on a postcard – still preserved in one of his scrapbooks – an advertisement for a putative film, Private Chaplin U.S.A.: ‘Ladies and Gentlemen – Charlie in this picture lies [sic] down his cane and picks up the sword to fight for Democracy. Picture produced by Charlie Chaplin Film Corp. Released through First National Exhibitors’ Circuit.’ Chaplin’s collaborators and friends shook their heads about the wisdom of making comedy out of so dreadful an event as the war, the full impact of which Americans had recently begun to experience. Chaplin, nevertheless, always growing more aware of the proximity of comedy, drama and tragedy, was confident.

1918 – Daily production reports on A Dog’s Life, at first called I Should Worry.

1917 – Spanish cartoon depicting Chaplin with the Kaiser.

He seems to have begun the film with a more determined idea of its structure than was customary, though in the event this idea was to be modified. Originally he planned three acts. The first would show Charlie in civilian life, at the mercy of a virago wife, and the father of several children. After a bridging sequence in the recruiting office, the film would show his adventures at the front. The third part was to be ‘the banquet’, with the crowned heads of Europe gratefully toasting Charlie for his gallant capture of the Kaiser. At the end, like Jimmy the Fearless or Charlie in The Bank, he would wake up to the cold reality of the training camp.

When his plans were as certain as this, Chaplin liked to shoot his stories in sequence. He began with the scenes of civilian life, using three child actors, True Boardman Jr, Frankie Lee and Marion Feducha. The angry wife was to remain off screen, her presence indicated only by the occasional flying plate, frying-pan or other missile. As finally assembled, the sequence shows Charlie coming along the street with his three sons. Without any indication he turns into the door of a saloon, leaving them to wait patiently outside. When he rejoins them they all troop home, where he docilely sets about making soup for lunch amidst the bombardments of his unseen spouse. The arrival of the postman with his draft papers comes as a happy release.

The next sequence, which took two weeks to prepare and shoot, shows Charlie’s arrival at the recruiting office for his medical examination. He is told to enter the office and disrobe. Partially stripped, he opens the wrong door and finds himself trapped in a maze of glass-partitioned offices occupied by lady clerks. After much trouble Charlie evades the women. He reads on a door, ‘Dr Francis Maud’. The name makes him still more apprehensive; the doctor turns out to be no lady, however, but the lugubrious Albert Austin, heavily bearded. The examination is seen only in silhouette through the frosted glass panel of the office door. The doctor appears and sticks a gigantic probe into Charlie’s throat, only to have it repeatedly and violently shot back at him. Eventually Charlie swallows the thing entirely and the doctor is obliged to resort to a line and hook to retrieve it. No doubt suggested by memories of the Karno Harlequinade of Christmas 1910, in essence it is a hoary old routine of the vaudeville ‘shadowgraphist’. Chaplin was a master at giving new life to old jokes, though, and when, sixty-five years on, the rediscovered sequence was included in the Unknown Chaplin television series, it proved to have lost none of its verve.

Yet Chaplin was to discard all that he had shot in this first month of work. Such rigorous self-censorship would seem remarkable at any time in the history of the cinema. In 1918, when a month was reckoned time enough to shoot a first-class feature film, it was astounding. Moreover, under the contract with First National, Chaplin personally bore all the production costs. It was his own money that he was prepared to throw away in the cause of perfection. Rightly, though, he knew that he could do better.

The first week of July was devoted to revising the story and building new sets. When shooting was resumed, Chaplin filmed from beginning to end, practically without the breaks to talk over and revise the story which had become and were to remain customary. The most substantial interruption to shooting came on 11 July when Marie Dressler visited the studio, accompanied by the actress Ina Claire. As usual, Chaplin abandoned work with surprising cheerfulness to entertain his old co-star. They posed together for photographs, which show the formidable Marie in Hun-scaring mood in the trench set.

The trench and dug-out are a remarkable abstraction of the reality of the Western Front. When Chaplin reissued Shoulder Arms more than half a century later, he proudly prefaced it with actuality shots of the war, to show how well his set-builders had done. The trench scenes, showing Charlie, Sydney and their companions adapting to front-line conditions – vermin, bad food, homesickness, snipers, rain, mud, floods and fear – took four weeks to shoot. By this time it was high summer. One day the heat was so great that it was impossible to film at all. Chaplin spent four days of this heatwave sweating inside a camouflage tree. His discomfort was rewarded by one of the most deliriously surreal episodes of his career. Charlie scuttles around no-man’s-land in his tree disguise, freezing into arboreal immobility at the approach of a German patrol, and coping ingeniously with a great German soldier with an axe who is bent on chopping him down for firewood. In our last memorable vision of the Charlie-tree it is skipping and hopping off towards a distant horizon. The expanses of no-man’s-land were provided, in those days of a still-rural Hollywood, by the outskirts of Beverly Hills, while Wilshire Boulevard and the back of Sherman provided the forest. Behind Sherman, too, they found a half-buried pipe which suggested a piece of comic business. Charlie bolts, rabbit-like into the pipe; his German pursuers grab his legs, but capture only his boots and his disguise which he has shed like a snake-skin. Following this, rotund Henry Bergman, playing a German officer, gets stuck in the pipe as he goes after Charlie, and has to be broken out. It is not recorded if the Los Angeles sewage authorities ever discovered how their property came to be shattered.

Dedicated to his patriotic role, Chaplin had agreed to donate a short film to the Liberty Bond drive, and now realized that to deliver it on time he would have to interrupt production of Camouflage, which had inevitably overrun its anticipated schedule. On 14 August the unit worked on until 1 a.m., to complete the scenes of Private Charlie’s encounter with Edna, playing a French peasant, in her ruined home. The next day the studio was turned over to making what was identified only as ‘propaganda film’. Eventually titled The Bond, it ran 685 feet (about ten minutes) and was completed in six working days. Sydney appeared as the Kaiser in the costume and make-up he used for Camouflage. Besides Chaplin, the rest of the cast was made up of Edna, Albert Austin and a child called Dorothy Rosher – the future actress Joan Marsh. The film had four episodes, introduced by the sub-title, ‘There are different kind of Bonds: the Bond of Friendship; the Bond of Love; the Marriage Bond; and most important of all – the Liberty Bond.’ The use of simple, stylized white properties against a plain black backdrop gave this curious little film a proto-Expressionist look. It was donated to the government, and distributed without charge to all theatres in the United States in the autumn of 1918. With The Bond out of the way, Chaplin rapidly finished off Camouflage. By 16 September the film was cut, and retitled Shoulder Arms.

Chaplin, now feeling tired, dispirited and depressed by personal troubles, suddenly lost confidence in the film and later claimed that he had seriously thought of scrapping it. He was incredulous when Douglas Fairbanks, having demanded to see it, laughed till the tears ran down his cheeks. Better than any other clown in history, Chaplin was able to prove that comedy is never so rich as when it is poised on the edge of tragedy. He had metamorphosed the real-life horrors of war into a cause for laughter; in the event there was no audience more appreciative of Shoulder Arms than the men who had seen and suffered the reality. Soldier Charlie includes in his kit a mousetrap and a grater which serves as a back-scratcher when the lice grow too assertive. His food parcel from home includes biscuits as hard as ration issue, and a Limburger cheese so high that he uses it like a grenade to bomb and gas the enemy. He takes advantage of passing bullets to open a bottle and light a cigarette. As a sniper, he chalks up his hits – then rubs out the last mark in acknowledgement of a return shot that clips his tin helmet. Even the nightmare of the flooded trenches of the Somme is turned into laughter: Charlie fishes out his submerged pillow to plump it up ineffectually before settling down for the night, and blows out the candle as it floats by on the flood water. One sub-title became a classic joke of the First World War. Asked how he has captured thirteen Germans single-handed, Charlie replies simply and mystifyingly: ‘I surrounded them.’

Just as memorable is the scene where Charlie is the only soldier to receive no letter or parcel in the mail delivery. With misplaced pride he refuses an offer of cake from a luckier comrade and wanders from the dug-out into the trench. There a soldier on guard duty is reading a letter from home. Charlie reads over his shoulder and echoes all the emotions that are passing over the soldier’s face. Though he might make comedy from it, the folly and tragedy and waste of war were always to bewilder and torment Chaplin. One apparently light-hearted scene in Shoulder Arms already hints at a more serious drift of thought. Charlie, having ‘surrounded’ and captured his German prisoners, offers them cigarettes. The common soldiers accept them gratefully, but the diminutive Prussian officer takes a cigarette only to throw it away with contempt. Charlie instantly seizes the little man, lays him across his knee and spanks him soundly. The German soldiers delightedly gather around and applaud. There is a comradeship of ordinary men that transcends the warring of governments and armies.

Shoulder Arms was one of the greatest successes of Chaplin’s career. Around this time, his personal life and marriage to Mildred Harris were less successful. When he met Mildred at a party given by Samuel Goldwyn, probably in the early part of 1918, she was sixteen. Already established as a child actress before she was ten, she was at this time employed at Paramount under the direction of Lois Weber. She still radiated a child-like quality which charmed Chaplin: his feminine ideal had been definitively fixed, it seemed, by his first infatuation with the fifteen-year-old Hetty Kelly. For her part, Mildred seems to have made knowing use of her golden hair, blue eyes and flirtatious prattle. She was presumably not discouraged by her mother, who as wardrobe mistress at the Ince Studios could not but be aware of Chaplin as the most eligible and the most handsome bachelor in Hollywood. Harriette Underhill described his appearance at this time: ‘He talks humorously, he thinks seriously, he dresses quietly and he looks handsome. He has the whitest teeth we ever saw, the bluest eyes and the blackest eye-lashes …’

Soon both Chaplin and the Harrises were coyly fending off enquiries from the press, who were not to be easily put off. On 25 June, the Los Angeles Times reported rumours of an engagement, and the subsequent denials. The following day the Los Angeles Examiner had a fuller and more circumstantial report:

CHAPLIN MARRIAGE RUMOR IS DENIED

Despite rumors that will not die down to the effect that Mildred Harris, the dainty screen favorite, has won the heart of Charlie Chaplin and soon is to be his bride, both the petite actress and her mother Mrs A. F. Harris denied last night the last half of the double-barrelled allegation.

‘No, Mr Chaplin and I are not engaged,’ Miss Harris said last night when she returned to her quarters in the Wilshire Apartments after an evening at his studio. ‘We’re just very dear friends. Why, we’ve only known each other two months and we’ve only been going together a month or so. I’m sure, too, Mr Chaplin will deny the report. We have not discussed the rumor as we have not seen each other for about a week.’

Mrs Harris was much surprised by the report, she said, and added that her daughter was only seventeen years of age and too young to think of marrying.

According to the circulated report in motion picture circles, Chaplin recently conferred with Philip Smalley [i.e. Phillips Smalley, Weber’s husband] of the Lois Weber Studio, where Miss Harris is employed, and asked how her contract would be affected if they should be married. It was said, according to the report, that the marriage would not affect the contract.

Philip [sic] Smalley denied that this reported conference took place.

Mrs Harris stopped her denials shortly after the completion of Shoulder Arms, when Mildred announced that she was pregnant. Chaplin was trapped: he could not possibly risk the scandal of this kind of involvement with a minor. Tom Harrington, his valet, secretary, confidant and general factotum, was told to arrange a registry office marriage for 23 September 1918, after studio working hours. Harrington arranged the affair with the discretion for which Chaplin valued him, and Chaplin now found himself, without any pleasure, a married man. Leaving the Los Angeles Athletic Club, which had been his home practically since he arrived in Hollywood, he rented a house at 2000 De Mille Drive. The lease was only for six months, but long tenancies were hardly appropriate to this marriage. His reaction on seeing the bride-to-be awaiting his arrival at the registry office was, to say the least, not promising: ‘I felt a little sorry for her.’

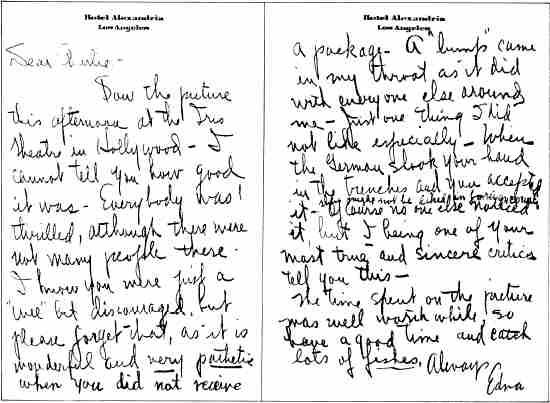

Edna only knew about the marriage when she read the newspapers the following day, but she accepted the fact with dignity and outward calm. Chaplin recalled that when he went to the studio the morning after, she appeared at the door of her dressing room. ‘Congratulations,’ she said softly. ‘Thank you,’ he replied, and went on his way to his dressing room. ‘Edna made me feel embarrassed.’ Edna did not see Shoulder Arms in the studio projection room with Chaplin, but when he was about to embark for a week of honeymoon on Catalina Island,9 she wrote to him:

To her other qualities Edna added that of being a noble loser. Poor Mildred was, as Chaplin gently put it, ‘no mental heavyweight’. She bored him, and in turn she resented the exclusive single-mindedness of his concentration when he was working. She was annoyed because he would not concern himself with her career, which enjoyed a brief stimulus from the celebrity of being Mildred Harris Chaplin. The worst irony for Chaplin was that the pregnancy which had shot-gunned him into marriage turned out to be a false alarm.

Chaplin was convinced that the marriage debilitated his creative ability, and the acute difficulties he experienced with his next film, Sunnyside, begun under the working title Jack of All Trades, appeared to confirm his fears. Chaplin’s ideas seemed much less clear than usual. He had decided on a rural subject, had turned the studio’s regular street setting into the main thoroughfare of an old-world village and built a set for the lobby of a seedy hotel, in which he was to play the man of all work who gave the film its (provisional) title. The first few days of shooting were spent on location at the Phelps ranch, and the petty cash disbursements that survive from this period are evocative of that far-off, rustic California. Mrs Phelps was paid $3 a day for the use of her ranch, a dollar a day for the hire of a cow, a dollar for repairs to a fence, and thirty cents a head for lunch for the unit in the ranch cook-house. Cowboys and horses were hired from a neighbouring rancher, Joe Floris.

Production began on 4 November, five weeks behind the scheduled starting date, but Chaplin’s desperate lack of a guiding idea was evident from the number of days he took off to ‘talk the story’ with Bergman and the others, and his readiness to seize on any distraction which offered itself. Work was abandoned so that Charlie, Sydney and Minnie Chaplin could lunch with the Bishop of Birmingham, whose visit to the studio was duly filmed. Another day Chaplin reported to the studio but then went off motoring with Carter De Haven in a ‘juvenile racer’. Later in the production the whole company took three days off to go to the air circus in San Diego, vaguely justifying the trip by shooting 2000 feet of film of the event, which was never used. In mid-December, Chaplin cut together what he had already shot, but was so dispirited that he absented himself from the studio altogether. Christmas came but Chaplin did not. Neither he nor Edna was seen at the studio in the first weeks of the New Year, and on 19 January 1919 the studio closed down altogether. In all, Chaplin stayed away from the studio for six weeks. None of his colleagues had ever witnessed him in such severe creative crisis.

Chaplin returned to the studio on 29 January, and announced that the 21,053 feet of film that had been exposed for Jack of All Trades was to be abandoned, and that he intended embarking on a new production to be called Putting It Over. This new project fared no better, however, and the situation was aggravated by a series of rainy days that prevented shooting. Chaplin tested some new actresses, hired a couple of cowboys and horses, a cow, a bull and a stunt man; then, after a few more days, he announced that they would after all resume work on Jack of All Trades, now called Sunnyside.

The studio daily reports tell their own story:

February 21 Did not shoot. Mr Chaplin cutting

February 22 Did not shoot. Mr Chaplin cutting

February 23 Did not shoot. Mr Chaplin cutting

February 25 Did not shoot. Looking for locations

February 26 Did not shoot. Mr Chaplin not feeling well

February 27 Did not shoot. Mr Chaplin cutting

February 28 Did not shoot.

March 1 Did not shoot. Filmed sunset, 100 feet.

March 2 Did not shoot. Talked story

March 4 Did not shoot. Talked story

March 5 Did not shoot. Mr Chaplin sick

March 6 Did not shoot. Mr Chaplin absent

March 7 Shot 376 feet

March 8 Did not shoot. Talked story

Suddenly, in the middle of March, Chaplin was seized either by desperation or by inspiration. By this time he had spent 150 days on the production, two thirds of them idle. Now, however, for three weeks he shot day in and day out, filming well over 1000 feet of film most days, and putting together the elements of a rough and ready but cohesive story. He developed a love interest between Edna and himself, with a rival in the shape of a dashing city slicker who arrives to turn her head with his natty clothes and gallant manners. (Was he turning life into art?)

Sunnyside betrays the strain that went into its completion, and Chaplin and his contemporaries regarded it as one of his least successful pictures. Certainly the comedy is neither so tightly structured nor so firmly motivated as in his other films of this period, but there are interesting departures from Chaplin’s usual manner, quite apart from the experiment of showing Charlie in a bucolic setting. He indulges in a peculiarly macabre device to get rid of the village idiot, while he is courting Edna. Blindfolding the youth under the pretext of a game of hide-and-seek, he gently guides him to the middle of the road, where the wretched creature stays for the rest of the film, threatened by oncoming traffic.

There is, too, a strange homage to L’après-midi d’un faune. The sequence begins with a cattle chase through the village after cowherd Charlie has allowed his charges to stray. He is tossed by the most ferocious of the beasts, lands on her back and is borne out of the village to be thrown, unconscious, into a ditch beside a little bridge. He dreams that he is awakened by four nymphs, who draw him to join them in an Arcadian dance. Charlie’s ballet becomes decidedly more animated after he has fallen backwards on a cactus. A brilliant if eccentric dancer, as he was often to demonstrate, Chaplin had been fascinated by the Ballets Russes on their recent appearances in Los Angeles, and flattered by the dancers’ admiration of his own mimetic gifts. Nijinsky and his company visited the studios, and when Chaplin went to see them in the theatre, the great dancer – who had recently left Diaghilev and was himself experiencing the problems of independence – kept the audience waiting for half an hour while he chatted to Chaplin in the interval.

The ending is more enigmatic than any other in Chaplin’s films. Seeing that he has lost Edna to the city slicker, he places himself deliberately in the path of an oncoming car. Abruptly the scene cuts to a swift and happy denouement, in which a truculent Charlie sends the city slicker packing in his automobile and wins back his Edna. To this day, critics have failed to agree whether it is the suicide which is the dream, or whether the happy ending is itself the wish-dream of the dying suicide. Sunnyside was finished, to Chaplin’s intense relief, on 15 April 1919, and premièred two months later.

There were other causes for Chaplin’s anxiety besides his cheerless marriage. As early as 1917 Sydney had been making efforts to bring their mother to California. Since Aunt Kate’s death, Aubrey Chaplin, Charlie’s cousin, had kept an eye on Hannah in Peckham House. It seemed an ideal opportunity to bring her to America when Alf Reeves came over in the autumn of 1917, and Sydney cabled him:

HAVE OBTAINED AMERICAN GOVERNMENT PERMISSION FOR MY MOTHER’S ADMISSION HERE FOR SPECIAL TREATMENT. CAN YOU BRING HER OVER WITH TWO SPECIAL NURSES? SEE AUBREY CHAPLIN 47 HEREFORD ROAD BAYSWATER HE HAS FULL PARTICULARS. IF SATISFACTORY WILL CABLE MONEY FOR FARE, CLOTHES.

At this time, Aubrey found that the necessary permits were not forthcoming from England, and Hannah remained in the home. By March 1919, however, Aubrey was able to write to Chaplin that he hoped that arrangements for Hannah’s journey would be completed by mid-May. Plagued by his marriage and his creative crisis, Chaplin suddenly realized that he could not face the pain of seeing his mother in her current condition on top of his other troubles. On 21 April he cabled Sydney, who was at the Claridge Hotel, New York:

SECOND THOUGHTS CONSIDER WILL BE BEST MOTHER REMAIN IN ENGLAND SOME GOOD SEASIDE RESORT. AFRAID PRESENCE HERE MIGHT DEPRESS AND AFFECT MY WORK. GOOD MAY COME ALONE.

Loyal Aubrey then set about finding a suitable haven on the English coast, and suggested she might be settled, preferably under an assumed name, at Margate, with a nurse and a companion. But for the time being she continued at Peckham House, her dull days varied by occasional rides out and visits from an old friend, Marie Thorne.

After a month’s break, Chaplin started on a new production – and his problems began all over again. The title, Charlie’s Picnic, suggested all sorts of comic possibilities. Chaplin tried out a number of children and chose five, True Boardman Jr, Marion Feducha, Raymond Lee, Bob Kelly and Dixie Doll, who were kept on the payroll for the next four weeks. During this whole period Chaplin managed to shoot only a few desultory scenes on two days. A sweltering summer was not conducive to inspiration. One day the studio clerk recorded ‘Hot as the devil’. On 16 June Chaplin gave up, dismissed the children and went out riding with Clement Shorter. A fortnight later he tried again. For four days at the beginning of July he struggled to film something – anything. He dragged in Kono, his chauffeur, to drive his car, and put Alf Reeves and a friend, Elmer Ellsworth, into a scene. Then the studio relapsed into inactivity. One day all the studio clerk could find to enter on his daily report sheet was ‘Note: Willard took a nap today’. History has left no clue to the identity of Willard – perhaps he was the studio cat – but the comment indicates the general desperation at the level of inactivity at Sunset and La Brea.

Not the least of Chaplin’s problems were domestic worries. Mildred was now really pregnant, and on 7 July gave birth to a malformed boy. Three days later, on 10 July 1919, the studio report laconically records: ‘Norman Spencer Chaplin passed on today – 4 p.m.’ and the next day: ‘11 July. Cast all absent … Did not shoot. Norman Spencer Chaplin buried today 3 p.m. Inglewood Cemetery.’ It was Mildred’s idea to inscribe on his gravestone ‘The Little Mouse’. Many years later Mildred recalled, ‘Charlie took it hard … that’s the only thing I can remember about Charlie … that he cried when the baby died.’ Chaplin told a friend bitterly that the undertakers had manipulated a prop smile on the tiny dead face, though the baby had never smiled in life.

It would be presumptuous to trace connections between this emotional shock and the sudden startling resurgence of creativity in Chaplin that followed it; or between the death of his first child and the subject of the film he was about to make, and which for many remains his greatest work. However, ten days after Norman Chaplin’s death, Chaplin was auditioning babies at the studio. He had meanwhile already found a co-star. In the depressed period which followed the completion of Sunny-side he had gone to the Orpheum and seen there an eccentric dance act, Jack Coogan. For the finish of his act Coogan brought on his four-year-old son, who took a bow, gave an impersonation of his father’s dancing, and made his exit with an energetic shimmy. Chaplin was delighted – perhaps it reminded him of his own first appearance on the stage when he was not much older than Jackie Coogan.

A night or two later, Chaplin met Jackie for the first time.10 He entered the dining room of the Alexandria Hotel with Sid Grauman, just as Jackie and his parents were leaving. They stopped and spoke: Grauman had known both Coogan parents in vaudeville, when he was managing theatres for his father; Mrs Coogan had toured the circuit as a child performer known as Baby Lillian. While Grauman and the Coogans were talking, Chaplin sat down beside Jackie so that he was on his level, and began to talk to him. Then he asked Mrs Coogan if he could borrow him for a few moments. Mrs Coogan was surprised, but Charlie Chaplin was Charlie Chaplin. As she later remembered, for an hour and forty-five minutes Chaplin and Coogan played together in the corner of the lobby on the Alexandria’s famous ‘million-dollar carpet’ (so called because of all the movie deals that had been made on it).

Eventually Chaplin brought the child back and said, ‘This is the most amazing person I ever met in my life.’ The moment of enchantment for Chaplin, it appeared, was when he asked Jackie what he did, and Jackie serenely replied: ‘I am a prestidigitator who works in a world of legerde-main.’ The phrase must have been one of the brilliant little mimic’s show pieces, but it could not fail to touch Chaplin with his own keen delight in words. Charmed as he was, Chaplin had still no thought of using Jackie in a picture, at this stage.

During the period of sitting around in the studio, waiting for inspiration for Charlie’s Picnic, Chaplin began to talk about the Coogan act. Somebody in the unit said that he had heard that Roscoe Arbuckle had just signed up Coogan. At once Chaplin kicked himself for not having had the idea of putting the boy into films himself. Wretchedly he began to think of all the gags he might have done with the child. The publicity man, Carlyle Robinson, made the happy discovery that it was the father and not the son who had been signed up by Arbuckle. The studio secretary, Mr Biby, was sent to see Jack Coogan, who agreed to let his son work for Chaplin. ‘Of course you can have the little punk,’ he said.

On 30 July Chaplin happily laid aside the 6570 feet of film he had already shot for Charlie’s Picnic, decided that the best of the infant aspirants he had auditioned was Baby Hathaway, and started to work on The Waif. Now his inspiration seemed to have returned: throughout August and September he worked in a fury of enthusiasm; there were no absences from the studio, no days off to ‘talk the story’ or to make outings to San Diego. Some days the unit would shoot more than 4000 feet of film, the footage of two two-reelers.

As usual Chaplin filmed the story in continuity; and the scenes he shot during these prolific weeks were to appear almost without revision in the definitive version of The Kid. Edna is seen leaving the charity hospital, a child in her arms, under the scornful gaze of a nurse and a gateman: in the completed film a sub-title succinctly explains her situation: ‘The woman – whose sin was motherhood’. Edna – probably intending suicide – leaves the baby in the back of an opulent car, with a note asking the finder to protect and care for him. (The car used for the scene belonged to D. W. Griffith.) The car is thereupon stolen by two murderous-looking crooks. Finding the baby in the back, they dump him roughly in an alley.

In the studio Charles D. Hall had created the attic setting which indelibly defines our vision of The Kid. It could be an illustration for Oliver Twist, with its sloping ceiling under the eaves, its peeling walls, bare boards, battered furniture and a door giving onto a precipice of stairs. It might – indeed must – be a recollection of the attic at 3 Pownall Terrace, where Charlie had bumped his head on the ceiling when he sat up in bed.

Here, in four days of shooting, Chaplin created the memorable sequence with Baby Hathaway, in which the Tramp, having unwillingly become the guardian of Edna’s mislaid child, teaches himself the crafts of childcare. He improvises a hammock-cradle, a feeding bottle made from an old coffee pot and (when with some concern he feels the moist underside of the hammock) a handy device consisting of a chair with a hole cut in the seat and a cuspidor placed beneath it. These homely details caused offence to a few more puritanical spectators at the time, but the audience at large loved them.

Chaplin moved on to the scenes in the same attic supposed to take place some five years later, when the baby has grown into Jackie Coogan. Jackie proved such a natural actor and apt pupil that most of this sequence was shot within a week. One or other of the Coogan parents was always on the set: Mrs Coogan during the early period while Jack Senior was still under contract to Arbuckle; later Jack Senior himself. They watched with delighted fascination Chaplin’s developing relationship with their son. It was a very real and close friendship. The two of them would disappear together to walk and play in the orange groves. They might spend hours watching ants at work, and Chaplin would enjoy explaining to Jackie the marvels of nature. For his part, Jackie was not really aware of Chaplin’s importance: he simply regarded him as the most remarkable man he had ever met.

Mrs Coogan, as she explained much later to her grandson, Anthony Coogan, felt that the relationship was one of great complexity. On one level Chaplin, in Jackie’s company, became a child. A large part of his gift, and that of the character of the Tramp, was his ability to see life from a childlike viewpoint. In his association with Jackie he was able to exhibit and extend this childlike behaviour. On another level Chaplin, off screen as well as on, adopted a paternal role with Jackie. It was impossible for people at the studio to resist the feeling that Jackie had replaced the child that he had just lost.

Above all, Jackie provided Chaplin with the most perfect actor he ever worked with. For the protean Chaplin, actors were necessary tools. Ideally he would have played every part in his films himself. Because he could not, he needed actors who could simulate his own performances. What he looked for in his actors was a perfect imitation of the looks and gestures and, later, intonations he would demonstrate. This was why more independently creative players were often irked; and why in some of the best performances we seem to be seeing Chaplin himself in someone else’s skin – man or woman.