10

The Gold Rush

Chaplin was now to embark upon the film by which, he sometimes said, he would most like to be remembered; and a marriage which for the rest of his life he would try in vain to forget. He recalled very clearly the moment when the inspiration for The Gold Rush came to him. On a Sunday morning in September or October 1923, he was invited to breakfast by Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, who, as his partners in United Artists, were anxious to see him start on a new film. After breakfast he amused himself looking at stereograms and was particularly struck by one showing an endless line of prospectors in the 1896 Klondike gold rush, toiling up the Chilkoot Pass. A caption on the back described the hardships the men suffered in their search for gold.

His imagination was further stimulated by reading a book about the disasters which befell a party of immigrants – twenty-nine men, eighteen women and forty-three children – on the trail to California in 1846. Led by George Donner, their misfortunes multiplied until eventually they found themselves snowbound in the Sierra Nevada. Of a party of ten men and five women who set out to cross the mountains to bring help, eight men died and the rest survived by eating their bodies. Before relief could be brought to those others who had remained in camp, many of them had also died, and the survivors, again, resorted to eating the corpses of their comrades, as well as dogs, cowhides and, it was said, their own moccasins.

Out of this unlikely material Chaplin was to create one of the cinema’s greatest comedies. ‘It is paradoxical,’ he wrote, ‘that tragedy stimulates the spirit of ridicule … ridicule, I suppose, is an attitude of defiance; we must laugh in the face of our helplessness against the forces of nature – or go insane.’1 Although he was as usual to work without a conventional script, improvising and developing new incidents as the shooting progressed, Chaplin seems to have had a much clearer sense of the eventual story line than at the start of most of his previous films. He worked fast on the first draft story and on 3 December 1923 – only two months after the première of A Woman of Paris – he was able to deposit for copyright a ‘play in two scenes’, provisionally entitled The Lucky Strike.

Throughout December and January Chaplin whipped along activity in the studio in preparation for what was now called ‘the northern story’. He continued to tinker with the scenario while his assistants – Eddie Sutherland, Henri d’Abbadie d’Arrast, Chuck Riesner and the indispensable Henry Bergman – compiled research data about Alaska. Props and costumes were meanwhile sought: dog-sleighs and fur coats were not too readily available in southern California. Danny Hall’s staff were feverishly building the elaborate sets required for the opening scenes of the film. Chaplin asked for a huge scenic cyclorama of a mountain background with a ‘snowfield’ of salt and flour in front of it. Hall also built the prospectors’ hut, arranged on a pivoted rocker and operated by an elaborate system of pulleys, for the scene in which it is supposed to have slid to the edge of a ravine, where it teeters perilously with each movement of the men within. The cameramen were, as usual, to be Rollie Totheroh and Jack Wilson.

The first actor engaged was Fred Karno Junior. The only players now on regular contract were Henry Bergman and Edna, but it soon became evident that Edna was not to be Chaplin’s leading lady. Even before A Woman of Paris, Chaplin had noted that she had grown too ‘matronly’ for comedy roles. Her drinking had made her weight unpredictable and her acting unreliable. Josef von Sternberg, who was to direct her last American film a couple of years later, said that she ‘was still charming, though she had not appeared in pictures for a number of years and had become unbelievably timid and unable to act in even the simplest scene without great difficulty’.2 To add to her problems, just as work was starting on The Gold Rush Edna was involved in one of the scandals that cast a shadow over Hollywood’s brightest years.

By coincidence the scandal also involved Chaplin’s previous leading lady, the unhappy Mabel Normand. The incident was never wholly explained. On New Year’s Day 1924 Edna was the guest of an oil magnate, Courtland Dines. She spent the day in his apartment, and in the afternoon they were joined by Mabel. Some time later, Mabel’s chauffeur arrived, apparently to take her home. There was an altercation between Dines and the chauffeur, who produced a revolver belonging to Mabel and fired. Dines survived, but Edna’s reputation did not. Middle America, with its cherished image of the innocent Edna, could not forgive such a disillusionment: the newspapers reported that her host, Dines, had been wearing only an undershirt and knee-length silk dressing gown and said he had been drinking all night and day, while all the parties involved claimed they could recall nothing of the event. Following the inconclusive courtroom hearings, a number of cities banned A Woman of Paris, and Edna withdrew from the limelight to her little apartment on the outskirts of the city.

Although there was no longer a deep emotional involvement, Chaplin retained his affection for Edna and his concern for her career. Certainly he was too loyal, too gallant, and too contemptuous of Hollywood gossip to let the scandal influence his decision not to use her in his film. But the incident cannot have helped Edna’s failing confidence and competence. When it was announced that he would choose a new leading lady, Chaplin was at pains to emphasize in press statements that there was no truth in rumours that Edna was no longer associated with his studios, and no long-term significance in her absence from the cast of The Gold Rush. ‘Miss Purviance is still under contract and receives her weekly salary as though she were actively engaged in production … Miss Purviance will again appear under the Chaplin banner, in a dramatic production supervised by Charles Spencer Chaplin.’

The news that Chaplin was seeking a replacement for his leading lady reached the ears of Lillita MacMurray, the Angel of Temptation in The Kid. Lillita was now fifteen years and nine months old. On Saturday, 3 February 1924 she presented herself in the studio accompanied by her best friend, Merna Kennedy, who was five months younger but had acquired a store of worldly wisdom as a child dancer in touring vaudeville. In the studio foyer they met Chaplin, who was talking to Alf Reeves. Chaplin greeted Lillita amiably as ‘My “Age of Innocence” girl!’ and was evidently impressed with the way her looks had matured since the expiry of her original one-year contract to the studio. Reeves was told to instruct Totheroh to make a screen test, which was done there and then.3

The following week, Chaplin made tests of the moving hut and the wind machines which were to provide the blizzard effects, and began shooting The Gold Rush on 8 February. The first scenes were for the sequence where Charlie, lost in the white wilderness, chances into the hut, is menaced by the villainous Black Larson, but is unable to obey Larson’s orders to leave the hut as he is continually blown back inside by the blizzard. Larson was played with great energy by Tom Murray, a vaudevillian who had toured throughout the English-speaking world with a blackface song-and-dance-act, Gillihan and Murray. When the scenes were completed and cut, Chaplin prepared to embark on a preliminary reconnaissance of Truckee, near the Donner Pass, where the location scenes were to be shot. He took with him Riesner, Totheroh and Hall.

Truckee stands beside Lake Tahoe, high in the Sierra Nevada, almost 400 miles north of Hollywood and just over twenty miles from Reno. At that time it boasted only one hotel, of very modest facilities: when Lita Grey and her mother later shared a room there, she noted that these facilities included a stove, a chamber pot and a cuspidor. The winter climate was bitterly cold; Chaplin could rely on all the snow he needed until the end of April.

Chaplin and his reconnaissance party stayed at Truckee from 20 to 24 February. When they returned to the studio the following week, there was a new addition to the cast – a large and sleek brown bear called John Brown, accompanied by his keeper, Bud White. The studio began to look like a menagerie when a Mr Niemayer and ten husky dogs were signed up a couple of days later. The bear had the privilege of two scenes with Chaplin. In the opening sequence of the film he pads silently after Charlie, who, unaware, makes his way along a precarious cliff path. In the hut scene, Charlie, blinded by a blanket that has become entangled about his head, grapples with the bear under the impression that it is big Mack Swain in his bearskin coat.

Meanwhile Chaplin had run Lillita MacMurray’s tests a number of times. Rollie Totheroh and Jim Tully – who was engaged to work both on the script and on publicity copywriting – were bold enough to express their dismay. Lillita was a big-boned, heavy-faced girl – cheerful enough, but hardly sparkling. Chaplin disregarded his colleagues’ adverse views and, on 2 March, Lillita MacMurray signed a contract to appear as leading lady of The Gold Rush at $75 per week. It was agreed that she should adopt the professional name of Lita Grey. Whatever his misgivings about her talent, Tully did a valiant job with the press. During the following weeks American newspaper readers were constantly regaled with Lita’s portrait and fulsome stories of her beauty, talent, charm, innocence and aristocratic lineage. ‘Her talent,’ runs a typical example of the florid prose of the popular press of the day,

is as yet in its formative period. Chaplin claims, however, that a rare spark is there and that with training she will develop a splendid talent. Of Lita personally there is little to say, for she knows so much less of life than does the average jazzy, effervescent flapper.

No love affairs have ever brought a quick beating to her heart, a flush to her cheeks. She idolizes Chaplin, but much as a child feels for some much older man who has shown her a great kindness. Romances constitute her favorite reading – and the glamorous deeds of yesterday’s heroes who walk across the pages of her history books.

One is conscious of an awakened something in her, as though some glow were breathing back of her large brown eyes, lurking upon her half-curved lips. She is so quiet, with that Spanish slumberous quality seeming to hold back her fires of expression until some moment of great feeling will liberate them to flame, one imagines, into beauty. Even her sports – swimming, horseback riding, tennis – she enjoys in leisurely fashion until that inherent dominant streak makes itself felt through her languor and gives her an animated grace.

It is as if she expresses two forces – the slumberous calm of her Spanish heritage that suggests dreamy, sunlit days of unhurried beauty, and a vitality that quivers beneath her tranquillity. Perhaps it is the spirit of those gallant Dons who braved the dangers of the New World for the glory of conquest, perhaps merely modern feminine independence struggling beneath the placid ivory loveliness of her. Whatever its origin, I have an idea that it is likely some day to make itself felt, to establish her as one of the unique personalities of the shadow-screen.

She dreams with her capabilities not yet fully awakened. When she speaks of the possibilities ahead, her eyes grow luminous and there is fire in them, and her pale face becomes mobile with her thoughts and feelings. She has a charming voice, of soft, musical cadence, rising in inflection when she becomes keenly interested, vibrant with what she is saying … 4

When she signed her contract, it was reported, Lillita/Lita jumped up and down, clapping her hands and crying ‘Goody, goody.’ The view of another journalist, Jack Junsmeyer, reveals a little more:

Schooling in the dance and the arts, supplemented by business college education and dramatic training has occupied the four-year interval following her only [sic] appearance on the screen in The Kid.

‘I have held firm to my ambition to go into pictures,’ says Miss Grey, ‘but I felt that I didn’t want to work with anyone except Mr Chaplin. Patience has its reward.’

Her first interview at the Chaplin studio revealed the new leading lady as a peculiarly shy, reticent and far from loquacious girl. She seemed phlegmatic.

But a few minutes later, in the presence of Chaplin on the set where his Alaska gold rush comedy is under way, the girl underwent a remarkable transformation. She bloomed with animation. She became galvanic.

Observation indicated that Chaplin wields a powerful professional sway over his new protégée – that almost hypnotic influence which the more masterful directors exert upon sensitive players before the camera.5

Every newspaper report said that Lita was nineteen. The studio publicity department felt it prudent not to publicize the employment of a minor, and Lita was sufficiently well-developed to make the subterfuge convincing.

During her first fortnight at the studio, Lita had nothing to do but watch. Chaplin moved on to his scenes in the cabin with Mack Swain as Big Jim McKay. The two men are snow-bound and starving. Jim takes it badly, in old-time melodrama style, clutching his head and declaiming ‘Food! I must have food!’ Charlie, with the flair of a Brillat-Savarin, stews his boot, which proves a less than satisfying meal. Big Jim, suffering hallucinations from hunger, imagines that Charlie is a plump hen and almost eats him.

Shooting the scenes of cooking and eating the boot took three days and sixty-three takes, throughout which, in his usual way, Chaplin was progressively refining and elaborating his comedy business. On the afternoon of the third day of shooting, for instance, he hit upon two of his most memorable transposition gags. Charlie’s dainty handling of the sole of the boot – he has graciously given Big Jim the more tender upper – transforms it into a filet; then, coming upon a bent nail, he crooks it on his little finger and invites Jim to break it with him as if it were a wishbone. The boots and laces used for the scene were made from liquorice and Lita Grey recalled that both actors suffered from its inconvenient laxative effects.

The scene of Charlie’s metamorphosis, in Mack’s crazed imagination, into a chicken, was similarly evolved during shooting. For several days the unit shot a version of the scene in which Mack simply sees the vision of a fine fat turkey sitting on the cabin table. When he grabs for it, it disappears, only to reappear in Charlie’s person, whereupon Mack chases him around the hut with a knife. When Mack comes to his senses a little, Charlie gives him a book to take his mind off food. However, on the Saturday (15 March 1924) Chaplin had a better idea, and when work resumed the following Monday the costume department had provided him with a man-size chicken costume. Now Big Jim would not merely imagine that he saw a turkey: Charlie would actually become a chicken.

The film cameramen of those days had to be resourceful. Their cameras were technically excellent, but had few of the refinements commonplace in present-day apparatus. Moreover, effects like fades, dissolves or irises, which in later years were made in the laboratory, still had to be done by the camera. This was the case with the chicken transformations in The Gold Rush. Chaplin would start the scene in his ordinary costume. At a given moment the camera would be faded out and stopped. The scene and camera position would be kept unchanged while Chaplin rapidly changed into his chicken costume. At the same time the camera was wound back to the start of the fade, the place where the transformation was to begin. While the camera started up and faded in, Chaplin would precisely retrace the action he had just filmed. In this way, the two images of Charlie and the chicken would be exactly superimposed so that the two figures would seem to dissolve into one another. Precisely the same technique was needed to turn the chicken back into Charlie. During the pause for the costume change Mack Swain, who was also in the scene, had to stay absolutely motionless. To help him, he was seated at a table with his head firmly supported on his elbows. The precision and faultless matching of the effect is a remarkable tribute both to the technicians and to the actors. The feat appears even more remarkable when it is remembered that the cameramen were simultaneously covering the scene with two cameras. In the film it is made to seem quite effortless and, as Chaplin would have wished, the magic remains intact.

The peculiar genius for perceiving in one object the properties of some other item – which was the basis of a lifetime of ‘transposition’ gags – is here seen at its most developed, as Chaplin discovers the chickenish properties in his own person. The ‘dissolve’ is not only in the camera but in his own mind and physique. He discerns, in the manner that Charlie flaps his arms and in his toes-out waddle, those characteristics which coincide exactly with the movements of the chicken. Eddie Sutherland recalled that for one shot, another actor was substituted in the chicken costume. It did not work. The actor was able only to be a man in a chicken costume. Chaplin, at will, could become that chicken.

For the publicity material for the film, Jim Tully6 wrote a description of Chaplin at work on the starvation scenes in the cabin:

There are present neither mobs nor megaphones. There is a minimum of noise. The cameramen, property men, electricians all speak amongst themselves in hushed whispers when they speak at all. For the most part they look into the center of the set in much the same way as the Sunday flock looks at its pastor. For there gesticulates Charlie Chaplin.

‘Great! Now just one more for luck …’

Only three scenes were taken in the entire afternoon, but the proof that Mr Chaplin is without doubt the hardest working individual in Hollywood is that each scene is shot at least twenty times. Any one of the twenty would transport almost any director other than Charlie; he does them over and over again, seeking just the shade to blend with the mood. And his moods are even more numerous than his scenes.

‘Just once more – we’ll get it this time!’ It is his continual cry, ceaseless as the waves of the sea. And each additional ‘take’ means just three times as much work for him as for anyone else.

Perhaps in the middle of a scene when everything seems to be superlative, he will stop the action with a gesture, ‘Cut’ – he walks over to a little stool beside one of the cameras and leans his head upon the tripod. The cameramen stand silently beside their cranks; everyone virtually holds his breath until Charlie jumps up with an enthusiastic yell:

‘I’ve got it. Mack; you should cry: “Food! Food! I must have food!”7 You’re starving and you are going to pieces. See – like this!’

Mr Swain, a veteran trooper, watches intently as Charlie goes through every detail of the action.

‘Let’s take it!’ Charlie suddenly exclaims. ‘What do you say, Mack?’

‘Sure,’ answers Mack.

And again the scene is re-enacted and recorded by the tireless cameras.

Now, finally, it was time to shoot Lita’s first scene, which was, in fact, to be the only scene for The Gold Rush which she shot in the studio. Chaplin seemed sometimes to have an eerie gift of presentiment. In The Kid Lita had appeared in a dream sequence as the Angel of Temptation whose blandishments (in his dream) bring about the Tramp’s death. In The Gold Rush, also, she was to appear in a dream. As first conceived, the scene had Charlie sleeping in the cabin. He dreams that he is awakened by a beautiful girl (Lita) who brings him a large plate of roast turkey.

The scene, the setting for which was a dream kitchen, was begun on Saturday, 22 March 1924. When he returned to the studio the following Monday, however, Chaplin had quite a new idea. The turkey was to be replaced by a big, beautiful strawberry shortcake. The new action is described in the day’s continuity reports. The final take, completed at 6.30 p.m., was thus:

Scene 14: Close-up. Dissolve. C. asleep in kitchen on couch. Lita standing over him with cake – wakens him – he sits up – she sits down beside him – smiles – takes berry – gives it to him – he turns forward – eats it – smiles – she takes another berry – starts to give it to him. She says: Close your eyes and open your mouth. He does so and she throws whole cake in his face and laughs. C. takes cake off – face all smeared with cream – Fade out and fade into close-up in cabin with C. asleep in cot – blanket over body but not on head – snow on neck and face – snow drops down from roof five times – he wakes up then sits up – and looks around room – brushes snow off – gets up – comes forward left of camera. O.K.8

The scene, which was never to reach the screen, was to prove a vivid metaphor for the sad story of Charlie’s future relationship with Lita.

The succeeding fortnight was spent in cutting and reshooting the cabin scenes with Mack Swain: it was probably at this time that Tully wrote his description of Chaplin at work. Now preparations began for the great trek to Truckee to film at the locations selected by the February advance party. The first group, consisting of Eddie Sutherland, Danny Hall, seven carpenters, four electricians and Mr Wood the painter, left on 9 April. The following day the camera crew and a Mexican labourer, Frank Antunez, followed. A week later they were joined by the main party: Chaplin attended by Kono, Lita chaperoned by her mother, Mrs Spicer, Henri d’Abbadie d’Arrast, Jim Tully, Tom Murray, Mack Swain, Della Steele (the clerk who made up the daily continuity reports), several assistants and handymen, and Bud White and his bear. The journey, though long, was not uncomfortable: the party travelled in private rail cars, with drawing rooms and dining rooms. Despite (or perhaps because of) Mrs Spicer’s watchful presence, Lita sensed a growing mutual interest between herself and her employer that was more than professional.

Eddie Sutherland had efficiently prepared everything so that the morning after his arrival Chaplin could direct the opening scene of the film, which remains one of the most memorable in cinema. Again, Tully has left a colourful description of the occasion:

To make the pass, a pathway of 2300 feet long was cut through the snows, rising to an ascent of 1000 feet at an elevation of 9850 feet. Winding through a narrow defile to the top of Mount Lincoln, the pass was only made possible because of the drifts of eternal snow against the mountainside. The exact location of this feat was accomplished in a narrow basin, a natural formation known as the ‘Sugar Bowl’.

To reach this spot, trail was broken through the big trees and deep snows, a distance of nine miles from the railroad, and all paraphernalia was hauled through the immense fir forest. There a construction camp was laid for the building of the pioneers’ city. To make possible the cutting out of the pass, a club of young men, professional ski-jumpers, were employed to dig steps in the frozen snows, at the topmost point, as there the pass is perpendicular and the ascent was made only after strenuous effort.

With the building of the mining camp, and the pass completed, special agents of the Southern Pacific Railway were asked to round up 2500 men for this scene … On two days a great gathering of derelicts had assembled. They came with their own blanket packs on their backs, the frayed wanderers of the western nation. It was beggardom on holiday.

A more rugged and picturesque gathering of men could hardly be imagined. They arrived at the improvised scene of Chilkoot Pass in special trains; and, what is more, special trains of dining cars went ahead of them. It was thought best to keep the diners in full view of the derelicts …

They trudged through the heavy snows of the narrow pass as if gold were actually to be their reward, and not just a day’s pay. To them what mattered [was]: they were to be seen in a picture with Chaplin, the mightiest vagrant of them all. It would be a red-letter day in their lives, the day they went over Chilkoot Pass with Charlie Chaplin.9

Tully is guilty here of some exaggeration. The studio records show that 600 men were brought from Sacramento, not the 2500 he claims. They were supplemented by every member of the unit not otherwise occupied. Sutherland, Lita and her mother all joined the trail.

Chaplin was very concerned to sustain morale in the discomfort, bitter cold and tedium of Truckee. On Monday he shot one scene of the cabin sliding down the mountainside. Then, while the carpenters were making changes to the cabin set, he joined the unit in bob-sledding and ski-racing. As a result, the following day he was confined to bed with a chill. Two feet of snow had fallen in the night, and the snowstorm continued. The storm was an opportunity too good to be missed, so in Chaplin’s absence Eddie Sutherland shot some effective scenes of Tom Murray as Black Larson, battling through the blizzard with his sledge.

Though still sick – as surviving photographs clearly reveal – Chaplin was up and about again the next day: he was eager not to prolong the costly and uncomfortable stay in Truckee. Material was shot for some action that was not to figure in the final film, involving Tom Murray’s partner, played by Eddie Sutherland. In one scene they were filmed together outside the cabin; in another they rescue Lita from the assault of a villainous prospector played by Joseph Van Meter, for many years a general assistant at the Chaplin studios and blessed with a mean face which came in handy whenever Chaplin needed an extra for a nefarious role. Other scenes shot in the Truckee snow showed Charlie finding a grave marked ‘Here lies Jim Sourdough’; Bud White’s bear prowling around the cabin; and Big Jim chasing the Charlie-chicken across the snowy wastes. Mack Swain had by this time also succumbed to ’flu, so Sid Swaney stood in for him in these scenes. The last day of location shooting was 28 April. The four cameras were again used for a shot of Charlie sliding down ‘Chilkoot Pass’. Then Chaplin, with Kono, Bergman, d’Arrast and Mack Swain, took the train for Los Angeles via San Francisco. The unit stayed behind to tear down the sets: on the evening of the 29th what remained was burned after dark and Sutherland filmed the conflagration, in case it might come in handy. That night Lita and her mother, the camera crew, Danny Hall and some others boarded the train home.

Everyone was back by 2 May. Having captured his snow scenes, Chaplin shot nothing more throughout May and June, and the company grew restive. While Chaplin worked over script and gag material with Bergman, d’Arrast and Tully, and Lita was photographed for stills in different costumes and coiffures, the scenic department was occupied with the problems of recreating Alaska in the studio during a California summer. Even though extra labour was brought in (Tully’s publicity claimed that 500 scenic craftsmen had been employed) they were hard pressed to complete the sets in the eight or nine weeks allotted to them. A small-scale mountain range was built. Its ‘snow-capped’ peaks, glistening in the sun, were visible miles off, and brought hundreds of curious sightseers for a closer view. Tully published some statistics on the making of the mountains. The framework required 239,577 feet of timber, which was covered with 22,750 linear feet of chicken wire, and over that 22,000 feet of burlap. The artificial ice and snow required 200 tons of plaster, 285 tons of salt and 100 barrels of flour. The blizzard scenes called for an additional four cart-loads of confetti.

Other miscellaneous items from the hardware bills on The Gold Rush included 300 picks and shovels, 2000 feet of garden hose, 7000 feet of rope, four tons of steel, five tons of coke, four tons of asbestos, thirty-five tons of cement, 400 kegs of nails, 3000 bolts and several tons of smaller items.

Shooting resumed on 1 July, with more scenes of Chaplin and Mack Swain hungry in the cabin. A pleasant gag sequence, which was ultimately rejected, had the two of them playing cards. Mack falls asleep over the game, but with his elbow too firmly planted on his own cards to permit Charlie to take advantage with a little cheating. Instead, Charlie constructs a toy windmill and playfully powers it with Mack’s windy snores. These scenes finished, he moved on to the sequence in which the cabin slides to the edge of the chasm, where it delicately balances, responding to every move and cough of the two men inside. This required work with miniature models. In the early 1920s there were no special effects firms in Hollywood to entrust with this kind of work: all depended on the skills of the studio’s own cameramen, production designers, set builders and property men. Nevertheless, the miniature work in The Gold Rush is exemplary. The cuts from the full-size hut to the model are barely perceptible: sometimes, when the viewer thinks he has detected the model, he is suddenly made aware of his error. The continuity reports of the shots made with models suggest that Chaplin contemplated a scene – anticipating the opening of The Wizard of Oz – in which the hut and its occupants would whirl through the blizzard:

Scene 2175: L.S. camera on moving platform – l. to r – trees in foreground moving 1. to r. – background storm effect – panorama for insert where C.C. looks out window house going 90 m.p.h.

In the last days of September 1924 Chaplin shot a few more scenes of the cabin in the snowstorm, but by the end of the month all work had come to a halt. Chaplin was to shoot nothing in his studio for the rest of that year. He had been stopped dead in his tracks by the bombshell delivered by Lita. Some time towards the end of September she announced that she was pregnant. She had a mother aflame with outrage, a grandfather who literally toted a shotgun and an uncle who was a lawyer in San Francisco. Where minors were concerned, the Californian law afforded a charter to shotgun weddings: for a man to have relations with an underage girl constituted, de facto, rape, carrying penalties of up to thirty years in jail. Lita’s family held the trump card and would hear of no solution but an immediate marriage. Chaplin had again trapped himself with a hopelessly incompatible partner.

The press for once suspected nothing. Chaplin and his young leading lady had been seen in public a good deal, but always chaperoned by Lita’s mother or by Thelma Morgan Converse, the sister of Gloria Vanderbilt, whom the gossips had decided was Chaplin’s secret fiancée. As Lita explained, more than sixty years later:

Charlie’s chaperone subterfuge was working well, and the three of us regularly enjoyed evenings at the Montmartre Café or the Ambassador Hotel … No matter where we went, the evening would always conclude with our dropping off Thelma early at her home, and then the two of us would spend some time alone at his Beverly Hills house …

We would invariably end the evenings in his bedroom; he always wanted to make love to me. Contraceptives were never used; Charlie believed that there was no danger of my becoming pregnant. I was young and totally inexperienced – I had never even been on a date before – and I had such complete hero worship for Charlie Chaplin that I trusted him implicitly. As I look back on those evenings, it astounds me that Charlie was never troubled by the possibility of my becoming pregnant. I can only attribute this to the childlike nature of the man.

After a short while, Thelma Morgan Converse became aware of her true role in our frequent nights out. In the middle of dinner at Musso and Frank Grill one evening, she walked out and refused to have anything further to do with Charlie. I was now without a chaperone.10

According to Lita’s account, Chaplin subsequently invited Lita and her mother to stay over at the house, and it was on this occasion that Mrs Spicer discovered what was going on. ‘I did not hear from Charlie for about two weeks, and at the end of that time it was discovered I was pregnant.’

Several weeks passed, but Charlie seemed unwilling to discuss the possibility of marriage. What Charlie wanted was to arrange for an abortion as soon as possible. If I was unwilling to do that, his other offer was to pay me $20,000 to marry someone else.11

For the moment the press were quite distracted by another scent. On 16 November, Grace Kingsley, the columnist of the New York Daily News, reported:

Charlie Chaplin continues to pay ardent attention to Marion Davies. He spent the evening at Montmartre dining and dancing with the fair Marion the other night. There was a lovely young dancer entertaining that evening. And Charlie applauded but with his back turned. He never took his eyes off Marion’s blonde beauty.

This kind of item in a newspaper of a rival publishing group was not calculated to please William Randolph Hearst, who had been Marion Davies’ devoted and jealously possessive lover for almost nine years. Both Hearst and his wife had known and admired Chaplin for several years, and Hearst cannot have been unaware that the friendship between Chaplin and Marion was closer than with most of the men with whom she flirted. Marion was shooting Zander the Great at the same time that Chaplin was making The Gold Rush, and he would often pick her up after he had finished his day’s work. Marion’s biographer Fred Lawrence Guiles’s view is that

All of the cast and crew of Zander were aware that something was going on, but Marion was far too much like Chaplin for it to have been a meaningful affair. In the presence of others, they clowned together like an affectionate brother and sister, and it is difficult to imagine them being very different when they were alone together.12

Nevertheless, Hearst was, in Guiles’s words, ‘wounded in spirit and fretting what he should do’. In fact he returned to California from New York and on 18 November – two days after the appearance of Grace Kingsley’s squib – set off on his yacht the Oneida with a party of invited guests. Principal among these was the producer Thomas Harper Ince, whom Hearst was eager to persuade to become an active producer for his own Cosmopolitan Pictures company. Others on board, apart from Hearst and Marion, were the columnist Louella Parsons, the actress Seena Owen, the dancer Theodore Kosloff, the writer Elinor Glyn, Hearst’s secretary Joseph Willicombe, a publisher, Frank Barham, with his wife, Marion’s sisters Ethel and Reine and her niece Pepi, and Hearst’s studio manager, Dr Daniel Goodman. From all accounts, Chaplin also was on the boat, though he was later inclined to deny it. According to Guiles:

Hearst also invited Chaplin. Perhaps he thought that it was safe to do so, if he believed that he had broken up the romance; or he may have wanted to clarify Marion’s status a bit with Chaplin, since Chaplin seemed to have some doubts about it.13

What happened next is one of the great unsolved my steries of Hollywood. On 19 November, Ince was carried unconscious from the yacht at San Diego and died a few hours afterwards. The official story was that the cause of death was a heart attack brought on by ptomaine poison or acute indigestion. The persistent rumour, however, was that Hearst had discovered Ince and Marion together in the dimly lit lower galley and had pulled out a pistol and shot Ince. The question is whether or not the shooting (if it actually happened) was a case of mistaken identity: Ince was a small man with similar head shape and hair colour to Chaplin from the back view.

With time the rumour might have died, but for the startling contradictions in the evidence of all those concerned. At first the Hearst press gave out a story that Ince was taken ill at his ranch. Marion said that there were no firearms aboard, while Hearst’s biographer, John Tebbel, recorded that Hearst kept a gun aboard to pot the occasional seagull. There is great doubt as to whether or not Ince’s girlfriend, the actress Margaret Livingston, was aboard. Chaplin consistently declared to his intimates that he was not aboard the yacht, and in his autobiography is so hazy about the chronology that he asserts that Ince survived for three more weeks and was visited by Hearst, Marion and Chaplin. (However, photographs exist of Chaplin at Ince’s cremation, which took place forty-eight hours after the death.) Kono, according to Eleanor Boardman, then Mrs King Vidor, said that when he was meeting the boat, he saw Ince being carried off with a bullet wound in his head. Others said that the blood that was visible had been vomited from a perforated ulcer.

Elinor Glyn told Eleanor Boardman that everyone aboard the yacht had been sworn to secrecy, which would hardly have seemed necessary if Ince had died of natural causes. There was no inquest to settle the matter, though the San Diego District Attorney, the Los Angeles Homicide Chief and the proprietor of the mortuary where Ince’s body was taken, all declared themselves satisfied that there had been no foul play. So many decades after the event, there is little hope that anyone will ever satisfactorily explain the mystery, which remains, casting a shadow on all those who were, however remotely, concerned. Lita believed that it was no coincidence

that after months14 of stalling on marriage, Charlie finally decided to go ahead with our marriage less than a week after the Ince tragedy. It is merely conjecture on my part, but I feel that by marrying me, Charlie was also pacifying Hearst. It was a gesture that implied that in the future Charlie would confine his attentions to me and not Marion Davies.15

Three days after attending Ince’s funeral, Chaplin sent Lita, her mother and her Uncle Edwin off to Guaymas, Mexico, where they stayed at the Albin Inn. Deciding that the wedding, if there must be one, should at least be discreet, he devised an elaborate cover to elude publicity, and left the ingenious Kono to mastermind the details. On 25 November, a nucleus of the Gold Rush unit set off by train for Guaymas. Two newsmen, sensing a story, boarded the train and quizzed Chaplin, who successfully fobbed them off with the implausible story that he was setting some of the scenes of The Gold Rush in Mexico. ‘I’m very odd when I make pictures,’ he told them humorously. The following day, to lend conviction to his story, he hired a fishing boat and sent the camera crew out to shoot sea scenes. (The 1600 feet of film they shot that day still survive.) That evening Chaplin, Riesner, Lita and her mother drove to neighbouring Empalme, a dismal railway junction on the edge of Yaqui Indian territory, with sea on one side and desert on the other. Late at night the marriage ceremony was performed in his shabby parlour by a stout civil magistrate, Judge Haro, who spoke no English. In attendance were Kono, Nathan Burkan (Chaplin’s lawyer), Eddie Manson, a tearful Chuck Riesner and Lita’s mother, grandmother and uncle.

Chaplin was not a happy bridegroom. More than sixty years later, Lita recalled:

Words cannot describe how grim the wedding actually was. Charlie really outdid himself in arranging the most depressing marriage possible. To make matters worse, I was suffering from morning sickness on the day of the wedding.

After the brief ceremony, we convened for a wedding breakfast. It felt as if we had gathered for a wake instead of a wedding. Charlie was not in attendance. A few hours after the marriage, a morose Charlie went fishing with members of his crew. I did not see him again until late that night, when he joined me in the drawing room of the train headed back toward Los Angeles. I had heard him outside the drawing room saying to his entourage, ‘Well, boys, this is better than the penitentiary but it won’t last long.’

In our stateroom, Charlie said to me, ‘Don’t expect me to be a husband to you, for I won’t be. I’ll do certain things for appearances’ sake, beyond that, nothing.’

My throat was dry and I felt nauseated. ‘Please, would you get me a drink of water.’

‘Get it yourself. You might later claim I tried to poison you.’ I staggered to my feet and got the water.

After watching me for several minutes, Charlie said, ‘Come on, I’ll take you outside. The air will do you good.’ Standing on the platform of the observation car, I stared at the couplings of the train below, breathing deeply the cold night air. Charlie broke his aggressive silence and said to me, ‘We could put an end to this misery if you’d just jump.’

I pulled back closer to the entrance of the sleeping car. I could not believe what I was hearing. If there was ever a Jekyll and Hyde, it was Charlie Chaplin. It was the same Charlie Chaplin who had, only a short time ago, pledged his love for me. It was too much for me to understand. I went back to our stateroom, hoping he had just meant that remark as a joke.16

Chaplin planned to avoid the reporters on the return to Los Angeles. It was arranged that while the main part of the unit would go on to the Southern Pacific station, he and Lita, accompanied by Kono, would get off at the little whistle-stop station of Shorb, near Alhambra, where they would be met by the Japanese chauffeur, Frank Kawa.

Turning up his overcoat and pulling a derby hat over his ears, Chaplin, surrounded by a few close friends, helped his bride from the rear platform of the private car in which they travelled on their return from Empalme, Mexico, where they were married last Tuesday [sic].

Everything, it appeared, was working to a carefully scheduled plan whereby Chaplin was to return to his home in Beverly Hills with a degree of privacy rarely sought by film stars.

The comedian and his bride skirted a fence, looking for their limousine and Japanese driver. Just as they rounded a corner, they met ‘the press’. A movie camera, to which Charlie owes to much of his fame, commenced grinding away. Chaplin displayed impatience.

‘Can’t a man have a little privacy? I’ve been trying to avoid this. It’s awful!’ was the actor’s only comment to the reporters, who immediately began firing questions at him.

The limousine was sighted about a block away and Chaplin’s Japanese secretary was despatched to summon it. Meanwhile the comedian only turned up his overcoat further and with his bride tried to avoid facing the battery of cameras which were trained on him, and grumbled loudly at the fact that his Japanese chauffeur had apparently not understood his directions to run his machine as close to the tracks as possible.

‘Home,’ said Chaplin, and as a parting farewell to the newspaper men who had paid him so much attention, ‘I don’t want any publicity.’

A large group of studio friends, of the mistaken opinion that a royal welcome would please the comedian, had gathered at the Southern Pacific station, but were disappointed to find only the lesser lights of the Chaplin party who had remained aboard the private car as a supposed decoy for the newspaper men who were aboard the train.

After the newlyweds reached Chaplin’s new home in Beverly Hills, they were seen no more during the day.17

To reach the door of their home they had to run the gauntlet of a siege party at the gates of the house.

A leading article in the New York Daily News offered peculiarly wry congratulations to the newlyweds:

SPOILING A GOOD CLOWN

One of Charlie Chaplin’s screen comedies ended with the comedian doing a wild dash among the cactuses (or cacti) along the Mexican border. Then he was uncertain upon which side of the boundary lay safety. Now he has made a decision, but whether he considered safety in making it is a question.

The other day the comedian dashed across the border into Mexico aboard a train. His destination was Guaymas and his purpose was to wed Lita Grey, his leading lady. Marrying leading ladies seems to be a weakness among male screen and stage stars. Why, we don’t know.

But the practice seems to give weight to the old saying that ‘while absence makes the heart grow fonder, presence is a darned sight more effective.’ Leading ladies are usually present – and unusually effective.

We hope Charlie finds what he is supposed to be looking for – happiness. But he and his leading lady are about to tackle the toughest cross word puzzle of the ages – married life. So often there are more cross words than there are solutions; and frequently a synonym of four letters meaning ‘love’ is set down on the matrimonial patchwork as ‘bunk’.

We wish Mr Chaplin and Miss Grey the conventional quota of joy. But if they have to give up the puzzle we have this consolation. The best clowns have broken hearts. And no tragedy could be as great as spoiling the best clown of the screen by making him too happy.

Such a danger was remote. One of the incidental compensations of the marriage was that Chaplin threw himself feverishly back into work at the studio – no doubt to avoid spending time at home with his child bride, who forlornly realized that her position in her husband’s house was that of an unwanted guest. It may have been comforting to her when her mother moved in with them a few weeks after the marriage, though it may not have made life easier for Chaplin. His attitude seems to have veered from abusive to coldly courteous.

Despite the fact that Charlie was furious with me and resented my very presence in his home, he still wanted to have sex with me. I could not understand this in the beginning. At first, I thought it was a sign that he was breaking down his resentment and that he would soon be nice to me again, as he was before I became pregnant. I was wrong. A night’s intimacy meant nothing in the morning, and his tirades against me would begin again.18

Not long before her death, Lita confided to her son Sydney Chaplin, ‘I can say this about my sex life with old Charlie: not good … but often!’19

Lita’s pregnancy also obliged Chaplin to find a new leading lady for The Gold Rush, the production of which was clearly likely to go on for several more months. The press, meanwhile, were still kept in ignorance of Lita’s condition. Tully imaginatively told the newspapers that the former Miss Lita Grey had given up her role as the dance hall girl because now that she was married she wanted ‘to devote every moment of her time to her husband’.

Just before Christmas it was announced that the actress who would replace Lita was Georgia Hale, still quite unknown to the public. She was twenty-four. Born into a working-class family in St Joseph, Missouri, she had spent most of her life in Chicago. A striking, delicate beauty, at sixteen she won the title of Miss Chicago, which brought with it a cash prize and a chance to compete in the Miss America contest in Atlantic City. She was eliminated from that competition but her Chicago prize money enabled her to reach Hollywood in July 1923. Her hopes of work as a dancer were dashed by a fall in which she badly sprained her ankle, and when her money ran out she settled for work as a film extra. By chance, one of the first films in which she appeared, Roy William Neill’s By Divine Right, starred Mildred Harris, the first Mrs Chaplin. The film’s writer and assistant director was the young Josef von Sternberg, who was greatly impressed when he discovered Georgia reading his own translation of Karl Adolph’s novel Daughters of Vienna, and still more affected to see that she had dropped a mascara-stained tear on the page. When, a few months later, von Sternberg embarked on his own first film as director, The Salvation Hunters – a shoe-string experiment in an expressionist manner – he remembered Georgia Hale and cast her in the lead, paying her the same as her daily salary as an extra.

Von Sternberg’s partner and leading man, the English actor George K. Arthur, somehow succeeded in getting Chaplin to see the film (Sternberg claimed he had bribed Kono to smuggle it into the screening room at Chaplin’s home). Georgia Hale remembered:

George K. Arthur was a little devil. You couldn’t understand him: he had such a funny accent from some place in England [sic: Arthur was born in Aberdeen]. He was so cute. He was a promoter. He got Kono to put it on. Charlie fell in love with that picture. He thought it was a little gem. Von Sternberg was not a genius, but he had talent.20

Chaplin at once called up the Fairbankses, who came from next door to see the picture the same night. A day or two later he showed the film to Nazimova,21 and it was at this showing that he first met Georgia.

We met in the screening room at FBO Studios. He wanted Joe and me to be there for the show. I sat behind him and Nazimova. After the screening Joe said, ‘This is Georgia, the girl.’ He said, ‘Oh, I’m so happy to meet you.’ And then he lost interest in Nazimova and everyone else, and wanted to take me for tea. He asked me what I was doing, and I said I was doing fine. I had a regular daily understanding with Sennett. If I didn’t have anything else I could work there any day. He said, ‘Keep that up. That’s fine. But I want to keep in touch. I like your work.’

Then Douglas Fairbanks signed me to play the Queen in Don Q, Son of Zorro. I’d done a test and it turned out fine. All the costumes were ready, but then Charlie went to Doug and said: ‘You’ve signed the girl I need. I want her for The Gold Rush.’ However, they got together and agreed, and Douglas Fairbanks released me.

Now, he’d tested lots of people for the part. Everybody tested. One of them was Jean Peters – she became Carole Lombard. He invited me to see the tests, and I said to him, ‘But they’re wonderful!’ Because I thought I was terrible. In my test I just stood there looking mad and doing nothing. And they were all laughing and such. And he said, ‘That’s what I want. That’s the quality.’22

For Georgia it was a dream come true. She had idolized Chaplin long before she thought of Hollywood. As a child and adolescent in Chicago, psychologically bruised by her father’s insensitive discouragement of all her ambitions, she had discovered reassurance in the Tramp’s defiant resilience and had convinced herself of some mystical affinity with him. Working with him in no way disillusioned her.

You just knew you were working with a genius. He’s the greatest genius of all times for motion picture business. He was so wonderful to work with. You didn’t mind that he told you what to do all the time, every little thing. He was infinitely patient with actors – kind. He knew exactly what to say and what to do to get what he wanted.

One thing was that everything in his pictures was for real. Take the scene where I slap the boy [Malcolm Waite]. That slap was really for real. Charlie had had us doing that scene, and him pawing me, for so long, that I got really mad with him. I really did slap him – good and hard. And of course that was what Charlie wanted.23

The change of leading lady was not too disruptive since the character of the dance hall girl does not appear until halfway through the film – it is one of the odd aspects of its structure, but in the end product perfectly satisfactory. Since Chaplin was as usual shooting in story continuity, he had not yet arrived at the heroine’s scenes. The brief sequences which he had already shot with Lita were possibly intended as tests, and in the end had no place in the story. The rest of December was spent reworking the story, testing and costuming Georgia and organizing her publicity and photographs. Meanwhile, Danny Hall and his staff were building the big dance hall and bar where Charlie first meets Georgia.

The bar room scenes were difficult and costly, involving paying – and worse, keeping under control – as many as a hundred extras, who included Mexicans, Indians and, the pride of the unit, a proven centenarian, ‘Daddy’ Taylor, who was already over forty when he saw service in the Civil War. Chaplin was so delighted by the old man’s energy as a dancer that he gave him a brief scene of his own in the New Year dance sequence. Rates for extras had gone up since First National days: the base rate was now $7.50 a day, while some received as much as twice that sum. ‘Tiny’ Sandford, as the barman, was paid $20 a day. The highest daily rate on the unit, however, was paid to the dog which appears with Chaplin in the dance hall scene; seizing a handy length of rope to support his sinking trousers, Charlie fails to notice that it is attached to the collar of this heavyweight but docile animal. The dog, on hire from the Hal Roach studios, cost $35 a day.

Perhaps it was the celebrations of New Year 1925 that gave Chaplin the idea for setting the Tramp’s most poignant scenes on New Year’s Eve, when everyone else is celebrating, leaving the solitary prospector lonelier than ever. The dance hall scenes were finished on 19 January, when Chaplin filmed the comic-pathetic moment where the Tramp retrieves a torn and discarded picture of Georgia from the floor under the disconcerting gaze of a prospector of somewhat demented mien.

By the beginning of February the set-builders had completed the cabin supposed to be in the same township as the dance hall, where Charlie finds a home with the kindly engineer Hank Curtis (played by Henry Bergman). This was to be the setting for the New Year party which Charlie, with his meagre savings, prepares for Georgia and her friends. The girls forget all about him and fail to turn up. Waiting for them, Charlie falls asleep and dreams that the dinner party is a brilliant social success. The English music hall artist ‘Wee’ Georgie Wood, who knew Chaplin both in England and the United States, said that the scene was suggested by an incident in the young Chaplin’s days on tour, when he invited the members of another juvenile troupe, working another theatre, to tea. The manager of the troupe would not let them go, but nobody informed Chaplin, who vainly waited for his guests.

Chaplin seems to have been conscious that this sequence had to be something out of the ordinary. At most other studios in the silent period it was customary to employ instrumental groups, even small orchestras, to inspire the actors with mood music. At the Chaplin studios this was not considered necessary. Yet, exceptionally, for these hut scenes, musicians were employed on the set. The first week or so it was the Hollywood String Quartet,24 at $50 a day; after that the studio replaced them with Abe Lyman and a trio of players who did the job for $37.50 plus overtime. The famous ‘Dance of the Rolls’ which is the climax of the sequence was clearly filmed to music; every one of the eleven takes Chaplin made of the sequence was uniform in length, and when he subsequently added a music track to the film the routine synchronized perfectly to ‘The Oceana Roll’.

Famous though it was, this was not the first time that the ‘Dance of the Rolls’ had been filmed. In a two-reel comedy of 1918, Roscoe Arbuckle also speared two bread rolls with forks and made the miniature booted legs thus formed perform a little dance. Quite possibly it was a gag that both comedians had known and shared during their days together at Sennett. With Arbuckle it is an ingenious gag; with Chaplin it is touched with genius, in the dexterity, the timing, the expressiveness and reality of the dancing legs. The bread-roll feet become a living extension, their every move reflected in the face above them. The scene was initially shot quite casually, in the middle of a miscellaneous series of takes made late in the afternoon of 19 February:

Scene 3653: Great close-up –, C.C. at head of table – doing dance with rolls on forks.

Scene 3655: Retake scene

3656: Retake

Chaplin evidently liked the rushes, and the following day did eight further takes of the scene.

After more than a year, the end of shooting was in sight. The last big set to be constructed was the street of the mining town. The cheerful scene in which Charlie earns money for Georgia’s party by clearing snow, ensuring continued custom by shifting it from one door to the next, was finished in two swift days of shooting. On 10 April, Chaplin, Georgia and Mack Swain left for San Diego with a camera crew, to film the final scenes with Big Jim and Charlie, now millionaires as a result of Jim’s lucky strike, on the ship returning home. The scenes were shot on a boat called The Lark while it plied its regular route between San Diego, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Chaplin was clearly feeling relaxed; Georgia recalled,

Coming back, we went to a nightclub. When we went in they started to play ‘Charlie, My Boy’.

Then the band started to play a tango, and we danced, and everybody else got off the floor. He really loved that. You’d have thought it would have made him a million dollars, he was so pleased.25

The last scene (apart from some retakes of the miniatures) was shot on 14–15 May 1925. This was to be one of the most spectacular and surprising moments in the film: the end of the villainous Black Larson, when he plummets to his death as a chasm opens up in the ice and snow. Partly it was done with miniatures, though how the shots done to full scale and with the actor Tom Murray were made has never been explained. The collapse of a huge cliff-edge of snow and ice may have been arranged in connection with the dismantling of the mountain sets.

For nine weeks, from 20 April almost to the day of the première on 26 June, Chaplin was cutting the film. Meanwhile his domestic affairs were again encroaching. The couple had put a brave public face on their marriage. Cornered by the correspondent of the London People, Chaplin said, ‘I am the happiest married man in the whole world, and but for these malignant rumours, quite content.’ Asked about stories of a marriage settlement Chaplin replied, ‘The marriage settlement is just a wedding present to my wife, a present any man would give to the woman he loved.’ Lita in her turn said that she was ‘as happy as the day is long’, and that she had given up her role as leading lady to become the mistress of the nursery. She denied a rumour that Chaplin had moved back to his old quarters in the Los Angeles Athletic Club.

On 5 May 1925 Lita gave birth to a boy. Chaplin’s concern over the final stages of her pregnancy and his pride in the baby seemed to achieve a temporary rapprochement. He even reconsidered his earlier objection to naming a son Charles: hitherto he had declared that to give a child the name of a famous parent was to give it a cross to bear. In order to give no ammunition to Hollywood gossips, it was thought prudent to keep the child’s birth a secret for a while; it was still less than six months since the marriage in Mexico. So Lita, with her baby and her mother, remained hidden, at first in a cabin in the San Bernardino Mountains belonging to Dr James F. Holleran, the doctor who attended the birth and now (for a monetary consideration) falsified the birth registration. Subsequently they moved to a house at Manhattan Beach rented for them by Alf Reeves, whose wife Amy helped care for Lita when she suffered a post-natal illness. It was agreed that the baby’s official birthday should be 28 June – two days after the Los Angeles première of The Gold Rush.

While Lita fretted because he had no time to visit his first son, Chaplin laboured in the cutting room. In a shooting period that had spread over a year and three months, with 170 days of actual filming, he had shot 231,505 feet of film. From this mass of material he edited a finished film of 8555 feet. The longest comedy he had yet made, The Gold Rush was edited with unchecked narrative fluidity. The harmony of the scenes and the images betrayed nothing of the interruptions, the irritations, the technical effort. When Chaplin came to reissue the film with a soundtrack seventeen years later, the only significant (and inexplicable) change he made, apart from leaving out the sub-titles, was to the ending. The original version ended with Charlie and Georgia in a long and loving embrace. In the reissue Chaplin substituted a more chaste fade-out, with the two simply walking out of view.

‘A Chaplin première,’ said the Los Angeles Evening Herald, the day after the gala showing of The Gold Rush on 26 June 1925,

is always an outstanding event. Other stars and pictures attract great throngs, but a certain significance which attaches to the first presentations of films bearing the comedian’s hallmark makes his première just a little more important or, at least, it would seem so judging by the avidity shown by profession as well as public. There was not a vacant seat at the opening. If any ticket-holder preferred to stay away, he could have disposed of his coupons at a fancy figure …

The court in front of Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre was ‘a veritable fairyland of color and light. The most skilled decorators in the realm of make-believe had been at work for a week dressing the enclosure for the occasion.’ Inside, the celebrities were announced as they entered the auditorium by a stentorian voice, and each was applauded according to his or her degree of popularity. ‘The house rang with applause as favorites sauntered along behind attentive ushers.’ These announcements were an innovation, as was the chilled punch served by pretty usherettes in the interval. The film was preceded by a prologue ‘of matchless beauty … Grauman has actually outdone himself in this achievement and The Gold Rush première probably never will be surpassed. If it is, only a genius like Grauman can do it.’

The curtain rose on a panorama of the frozen north, revealing a school of seals mounting a jagged crag of ice. The seals were quickly joined by a group of Eskimo dancing girls. They were followed by a series of ‘impressively artistic dances by fascinatingly pretty young women wearing astoundingly rich and beautiful gowns all blending with the Arctic atmosphere and bespeaking the moods of the barren white country’. The numbers which followed included ice skating, a balloon act presented by Miss Lillian Powell and a Monte Carlo dance hall scene.

After the film, the director-star was led down to the stage. ‘He was too emotional, he explained, to make much of a speech and then, characteristically, he proceeded to deliver a fairly good one.’ Georgia noted that this was one of the rare occasions when Chaplin had no self-doubts about his work: ‘He was confident about that. He really felt it was the greatest picture he had made. He was quite satisfied.’26

Chaplin spent the next week refining the cutting of the film, and then a fortnight after that preparing a new musical score. Once there was no more work to be done, he was clearly eager to get away from Los Angeles and the house, and on 29 July left for New York by train with Kono and Henri d’Arrast, though the New York première was not until 16 August. Edna, who was on her way to Europe, joined Chaplin briefly in New York between 17 August and sailing for Cherbourg on 22 August.

In the big cities The Gold Rush was an instant success, but business was slower in the sticks. In January, Arthur Kelly of United Artists wrote to Sydney that The Gold Rush had

proved to be a flop in all the small cities. In fact it is rather disastrous to some of the exhibitors. Apparently they do not want to see Charlie in any dramatic work, which is proved by analyzing his gross receipts. On every engagement the opening broke all records, but immediately flopped on the second and subsequent days, proving that they had all made up their minds to go for a big laugh in which they were disappointed, and naturally a reaction set in. Perhaps this will be a tip to you on your future productions … 27

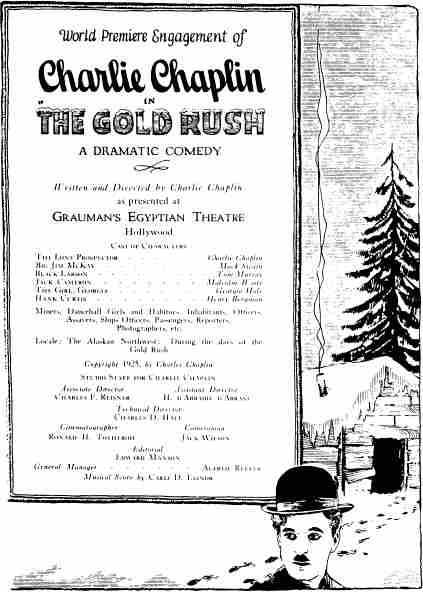

1925 – Page from première programme, The Gold Rush.

But Kelly’s fears proved unjustified. The Gold Rush had cost Chaplin $923,886.45; in time it would gross more than six million dollars.

In London, The Gold Rush opened at the Tivoli, Strand, which Chaplin had known as a music hall, but which had recently been converted into a luxury cinema. It made broadcasting history, or at least a rather bizarre fragment of it:

Next Saturday at 7.30 an attempt will be made to broadcast the laughter of the audience at the Tivoli Theatre during the ten most uproariously funny minutes of the new Charlie Chaplin film The Gold Rush. I hear that a preliminary experiment has been successful, but the BBC will not guarantee good results on the night itself, for this sort of transmission is a difficult and uncertain business.28

Evidently all went off well, however:

What so far has been the most original experiment in radio work was carried out by the British Broadcasting Company on Saturday evening last (26 September) when there was broadcasted to every station throughout the British Isles what was announced badly [?baldly] enough in every newspaper in the United Kingdom thus:

‘7.30 p.m. Interlude of Laughter. Ten Minutes with Charlie

Chaplin and his audience at the Tivoli.’‘Uncle Rex’, the broadcasting announcer, prefaced the item by stating that the B.B.C. were trying a unique experiment – that of broadcasting ‘a storm of uncontrolled laughter, inspired by the only man in the world who could make people laugh continually for the space of five minutes, viz., Charlie Chaplin!’ The episode chosen was that which forms the climactic scene of The Gold Rush when Charlie and his partner awake to discover their log cabin is resting perilously on the edge of a precipice.

This experiment, as reported by one listener-in, proved highly successful. The first outburst of laughter from the audience sounded like big crested waves breaking in fury against huge butting crags, and slowly dissolving in a thousand ripples and cascades that dropped like sea-pearls in an angry sea.

This was succeeded by a sound that echoed like the rolling of jam jars in an express train. Followed sounds of vague, whimsical crescendoes of delirious delight, which culminated in torrential laughter that finally broke out into a terrific uproar – a perfect storm of uncontrollable guffaws. Then shrieks of shrill but helpless laughter – and above them all the piercing silver-toned laugh of a woman which overtopped the thousand and one outbursts.

The climax came when one mighty outburst of laughter broke out in fullest fury, and sounding like salvoes of a thousand guns making the Royal salute. Gradually the laughter died away with sounds like an exhaust-valve, stuttering away its strength into thin air.

So ended what may be regarded as a historic event in film history – ten minutes of laughter with Charlie Chaplin at the Tivoli, London.29

The film’s première at the Capitol in Berlin was distinguished by the rare if perhaps not unique occurrence of an encore during a film performance. At the ‘Dance of the Rolls’, the audience went wild with enthusiasm. The manager of the theatre, with admirable presence of mind, rushed up to the projection box and instructed the projectionist to roll the film back and play the scene again. The orchestra picked up their cue and the reprise was greeted with even more tumultuous applause.30