14

Modern Times

Chaplin arrived back in Hollywood on 10 June 1932, having departed America on the last day of January 1931. On his return, he felt confused, disorientated and, above all, lonely; the house on Summit Drive was empty except for the servants. The first person he called was Georgia Hale, and they spent the evening together, dining by the fire. Chaplin had brought back two trunks full of souvenirs of the trip for Georgia, but late in the evening, as they ate cornflakes in the kitchen, she told him rather forcefully that all his presents did not make up for seventeen months without a word or a postcard. She refused his presents and left, telling him he need not trouble to telephone. He did not, and they were not to meet again for ten years. Like Edna, Georgia offered Chaplin disinterested friendship, loyalty and affection. But there were incompatibilities – Georgia had her own mind and opinions. She was also religious. ‘He used to say to me “Don’t start talking to me about God.”’ He was more than half in earnest.1

Chaplin soon realized he no longer felt at home in Hollywood. The place had changed since the age of golden silence, which was coming to an end when he began City Lights. During his absence, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford had separated, ‘so that world was no more’.2 There were different people and new techniques, and a new streamlined industrialization had supplanted artisan methods and pioneering enthusiasm. Chaplin was in no mood to take up battle with the talkies. In low moments after his return, he thought of selling up everything, retiring and going to live in China. (He never made clear why this was his choice for relocation.)

In his memoirs he admitted that he had had a vague hope of meeting someone in Europe who might orientate his life. Although this didn’t happen, there was soon to be a meeting on his doorstep in Hollywood. In July 1932, Joseph Schenck invited Chaplin for a weekend on his yacht. Schenck was accustomed to decorate his parties with pretty girls and on this occasion they included Paulette Goddard. Paulette, whose real name was Pauline Levy, was born in New York, most likely in 1911. At fourteen she was a Ziegfeld girl, then appeared in the chorus of No Foolin’ and Rio Rita, and landed a small part in Archie Selwyn’s play, The Conquering Male. At sixteen she married a rich playboy, Edgar James, but divorced him in the same year, whereupon she made her way to Hollywood. By the time she met Chaplin she had played bit parts in The Girl Habit, The Mouthpiece, The Kid From Spain and Kid Millions, and had signed a contract with the Hal Roach studio.

Paulette was beautiful, radiant, vivacious, ambitious and uncomplicated. She and Chaplin enjoyed an immediate rapport. There were similarities in their backgrounds – Paulette, too, came from a broken home and was the family breadwinner while still a child. They were both alone. At this first meeting, Chaplin was delighted to be able to give Paulette some financial counsel. She was still naive enough in Hollywood ways to be contemplating ‘investing’ $50,000 of her alimony in a dubious film project. Chaplin was just in time to prevent her signing the documents.

Soon they were seeing a great deal of each other. Chaplin persuaded Paulette to revert from platinum blonde to her natural dark hair; he also bought up her Roach contract. The press were soon hard on their heels, describing Paulette as a ‘mysterious blonde’. She did not remain mysterious for long. When Chaplin saw her off on the plane to New York on 19 September – he had stayed up with her all night at Glendale Airport – their farewell kiss made headlines across the continent. Both denied rumours of an engagement. The kiss was only friendly, said Paulette, adding that she was to be his next leading lady.

Meanwhile there were irritating reminders that Chaplin was still, in a way, a family man. In the years immediately following the divorce he had made little effort to contact his sons. They were still babies and the associations were still too painful. Now, however, Charles was seven and Sydney six. Before his departure for Europe he appears to have seen them a few times, mostly on the initiative of Lita’s grandmother. With their upbringing left largely to Lita’s mother, since Lita was trying to make a career for herself as a singer, they had grown into irresistibly attractive children. Ida Zeitlin, one of the most intelligent of the great generation of Hollywood ‘sob-sisters’, interviewed them for Screenland in the summer of 1932 and her shrewd assessment of their contrasting personalities might serve, with very little change, to characterize them in their maturer years:

Tommy [i.e. Sydney] is lively and venturesome, where Charlie is reflective and reserved. With Tommy, to have an idea is to act on it, but Charlie will think twice before he moves. Tommy is restless, turbulent, independent – Charlie is sensitive, high-strung and craves affection. Nothing is safe with Tommy – his toys have a habit of breaking apart in his hands. Charlie’s clothes are always folded at night and his small shoes placed carefully side by side. Tommy would sleep sweetly, says his grandmother, through an explosion, but there aren’t many nights when she isn’t awakened by an apprehensive little voice from Charlie’s bed: ‘Are you there, Nana?’ And only on being reassured does Charlie fall asleep again. Charlie has his father’s troubled temperament – Tommy, like his mother, is equable; and if signs mean anything, life is going to be considerably harder on Charlie than on his little brother Tommy.3

Miss Zeitlin cannot have known how accurate a prophet time would prove her.

While their father was away on his travels, Sydney and Charlie had also been in Europe. They had spent almost a year in and around Nice, where their still youthful grandmother had a gentleman friend, and where the boys learned French (they already spoke Spanish fluently, as well as English). Although they must often have been very near their father on the Côte d’Azur, there appears to have been no contact. In France, however, the children discovered with delight that being Charlie Chaplin’s sons made them celebrities too. Charlie learned that he could infallibly gain attention by imitating his father’s screen walk – a feat which Sydney, slightly pigeon-toed, could not master.

A week or so before Chaplin arrived back in America, Lita summoned the boys and Nana home: she had fixed up a film contract with David Butler to appear together with her sons in The Little Teacher. In New York the children were met by a battery of cameramen and reporters, but they were by this time professionals with the press. Charlie told them modestly that he was going to be a great actor and would like to play cowboys. Sydney said that he was going to be Mickey Mouse. ‘I am wondering,’ speculated Louella Parsons, with evident glee, ‘just how Charles Chaplin Senior will react to this.’ She was soon to discover. On 25 August, Loyd Wright, Chaplin’s attorney, filed a petition objecting to the boys working in motion pictures. Chaplin appeared in court on 27 August, but a further hearing was set for 2 September. On this occasion, Alf Reeves represented Chaplin. When Lita refused to accept Judge H. Parker Wood’s decision in Chaplin’s favour, a new hearing was set for the following day. Again Reeves represented Chaplin. Judge Wood’s decision was upheld. Lita announced she would appeal.

Lita’s persistence showed bad judgement in public relations. Opinion was unanimously with Chaplin. ‘A good mother,’ said the Boston Globe, ‘prefers a normal childhood for her children.’ Support for Chaplin came from unexpected quarters. Mildred Harris, who now had a six-year-old son of her own, Johnny McGovern, told the press:

I can understand Lita Grey Chaplin’s reluctance to decline a $65,000 contract which she probably reasons would mean a great deal to her boys’ future.

But I’d rather my child didn’t do anything till he’s old enough to know what he wants to do. I’ve been on the screen since I was eight. Child actors don’t have a hard life. It isn’t that. Quite the contrary. The danger is that they will be spoiled.4

The boys cried in understandable disappointment, but their father explained:

If you’re really in earnest about wanting to act, going into it now would be the worst thing in the world for you boys. You’d be typed as child actors. When you reached the gawky stage they’d drop you. Then you would have to make a complete comeback and you’d have a hard time of it, because everyone would remember you as those cute little juveniles. But if after you’ve grown up you still want to act, then I won’t interfere.5

In later years they appreciated his wisdom. At the time they were less convinced, partly because one of their playmates was Shirley Temple.

On 11 September a new hearing was granted, and Lita wrote a ten-page letter to Chaplin appealing for his agreement to allow the boys to work. Her letter reveals how keenly aware she was of the publicity backlash. She said she had taken up a theatrical career ‘in the hope that I might by such a contact with the public be able to remove the impression that I was coarse, vulgar and uneducated’.6

One happy outcome of the incident was that Chaplin began to see much more of his sons. From now on he tried to arrange some meeting or trip every Saturday. On 15 October he called for them as usual, but on entering the house was served with a subpoena to appear in court on 26 October: Lita’s lawyers were still short on delicacy. The case was again and finally decided in Chaplin’s favour. In court he found himself face to face with Lita’s lawyer uncle, Edwin T. MacMurray, who asked him, ‘What do you mean by the word exploitation?’ Chaplin had no hesitation in his reply: ‘You exploit something when you sell it, and you’re trying to sell the services of these little children. I want them to lead a natural existence of normal play.’7 Chaplin knew from memories of his own childhood what the alternatives could be.

The former husband and wife were in conflict once more the following February, when Chaplin questioned the administration of the boys’ trust fund. He insisted that a weekly savings account be set up for them – an arrangement for which they were duly grateful when they grew up and reaped the benefits. After this there was little contact between the couple except through the boys. Lita made a brief career as a vaudeville singer (‘She must like work, for it is four-a-day at the least,’ wrote Alf Reeves to Sydney) and drifted into an alcoholic breakdown, from which she was happily to recover. In 1936 she was playing at the Café de Paris in London, at the same time as Mildred Harris, now an acute alcoholic, was singing in a bottle club, where the two ladies briefly met for the first and only time.8

Meanwhile, Chaplin had come back to other troubles. The national economic situation had led to a general tightening up of taxation and the federal tax authorities were taking a keen interest in Chaplin’s affairs. They had estimated his taxable assets as the highest in the country, with taxable securities assessed at $7,687,570. Chaplin countered that the real value was only $1,657,316, and that the assessors’ investigators had used old values instead of actual prices. ‘They even charged me with $25,000 worth of old machinery which isn’t worth $500 today and film paraphernalia that they list at $25,000 would bring about $558.’9 The hearing was set for 14 July 1932. Sydney, in the South of France, was much concerned over his brother’s troubles and characteristically worried that not all possible economies were being made at the studios.

Alf Reeves tried to reassure him; but they were unlucky in having been allotted a ferret-like, relentlessly probing inspector. Alf had to break it to Sydney that he had started enquiries about a transaction in which some prop furniture had been written off the books and shipped to Sydney for use in his home. The inspector was charging that not only was the furniture improperly written off, but that it had been shipped under false declarations to avoid payment of French duty. The inspector was further demanding why no rental had been charged on Chaplin’s home – reckoned as a studio asset – during his eighteen-month absence in Europe. ‘And to add one more they are questioning Edna Purviance’s place on the corporation payroll and want to make it a personal charge.’

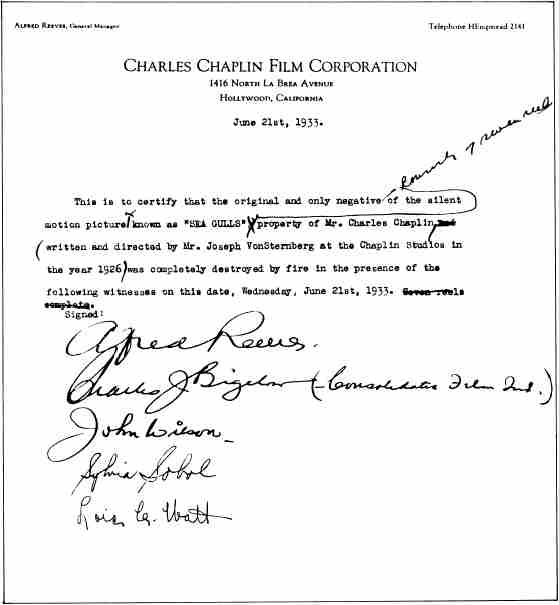

The Federal inspectors were pushing the studio hard. Some stocks were sold on poor terms – Alf reckoned a $200,000 loss – but stock losses were no longer admissible. They sought relief on the losses incurred in 1926 on the production of Sea Gulls. The condition on which the inspectors allowed this were that the film must be shown, by destruction, to be utterly devoid of possible future value. Hence on 21 June 1933, the ‘original and only negative’ of von Sternberg’s film was destroyed by fire in the presence of Alf Reeves, Jack Wilson, Sylvia Sobol, Lois G. Watt and Charles Bigelow, of Consolidated Film Inc., each of whom signed the affidavit to that effect. Though the fate of Josef von Sternberg’s negative is thus definitively established, there must have been at least one positive print, whose possible survival has kept film historians guessing ever since.

Sydney was also worried because Chaplin showed no signs of settling down to make a new film. For the moment he was otherwise occupied. Willa Roberts, the managing editor of Woman’s Home Companion, had trailed him to Europe and persuaded him to write a 50,000-word serialization of his European adventures for a fee of the same number of dollars. Chaplin was certainly more tempted by the challenge of writing than by the fee: he had, after all, just turned down the offer of $670,000 from the Blaine-Thompson advertising agency for a series of twenty-six fifteen-minute radio programmes, which he would be free to use in any way he liked. At that time the highest fee ever paid for a broadcast was $15,000, earned by Jascha Heifetz for a one-hour recital. Theodore Huff, in his 1951 biography of Chaplin, said that the ‘article’ (sic) was ‘ghost-written by his secretary, Catherine Hunter’; and the statement has been uncritically accepted by subsequent writers. It seems misleading: Chaplin was too proud and too perfectionist to allow someone else to write under his name. It is true that in the early days Rob Wagner may have shaped his thoughts on comedy into literary form while Monta Bell collaborated on Chaplin’s first published book, but there is a consistency of style, phrasing and vocabulary from My Wonderful Visit (My Trip Abroad) through A Comedian Sees the World – the title given to the Woman’s Home Companion series – to My Autobiography.

1933 – Certificate of destruction of the negative of Sea Gulls.

Chaplin found writing laborious – which is why he almost never wrote personal letters – and remained cavalier about spelling. But he loved words and was fascinated by them. In his youth he had made a practice of learning one new word from the dictionary every day, and in both his speech and writing he used words vividly and with the freshness of new discovery. When Richard Meryman interviewed him, at the age of seventy-five, he had just grown attached to the word ‘atavistic’. Meryman asked him what it meant and Chaplin explained, adding disarmingly: ‘I do like big words sometimes.’

His method was the same whether writing conventional prose or scripts. He would first write everything out in longhand and then dictate it to his secretary. Afterwards he would work over the typescript, and successive secretaries were astonished at how he would labour over a word, trying different positions or variations. The typing and correcting process might be repeated many times: he was as tireless in writing as in making films. He worked solidly on the Woman’s Home Companion articles from his return in July 1932 until late February 1933. Sydney, in Nice, was exasperated, and Alf Reeves attempted to reassure him:

Just a few remarks without the aid of the typist. Of course I understand your intent in commenting on time taken by C. in writing up his story – but you (knowing him as well as you do) realize that while he works hard – he works spasmodically – and all work and no play not being good for the health, he naturally plays quite a bit – possibly being in no great hurry in view of everything to make the government a present of the fruits of his labors whilst they are just sitting on the receiving end and making it hard for him at that – as far as they can. We know he could earn more by picturemaking and that the price he gets for the book whilst a lot in some people’s ideas is nothing compared to what he commands as an actor.10

Despite the unwelcome attentions of the Federal tax agents, this was one of the happiest periods Chaplin had yet experienced in his private life. He saw his sons regularly and they delighted him as much as he delighted them. ‘Oh, those wonderful weekends,’ Charlie Junior reminisced:

That wonderful magical house on the hill, with the man who lived there, the man who was so many men in one. We were to see them all now: the strict disciplinarian, the priceless entertainer, the taciturn, moody dreamer, the wild man of Borneo with his flashes of volcanic temper. The beloved chameleon shape was to weave itself subtly through all my boyhood and was never to stop fascinating me.11

Paulette was essential to it all and the boys fell in love with her the moment their father introduced her:

We lost our hearts at once, never to regain them through all the golden years of our childhood. Have you ever realized, Paulette, how much you meant to us? You were like a mother, a sister, a friend all in one. You lightened our father’s spells of sombre moodiness and you turned the big house on the hill into a real home. We thought you were the loveliest creature in the whole world. And somehow I feel, looking back today, that we meant as much to you, that we satisfied some need in your life too.12

Alf Reeves, who had watched Chaplin falling in and out of love for more than twenty years, was a trifle less romantic in his approval. ‘Charlie,’ he informed Sydney, ‘is still quite “chummy” with Paulette, who is a nice little “cutie”.’ Some time later, about the time that Modern Times was being finished, Reeves wrote to Sydney:

I spent a day with Charlie on a recent trip I made to the coast. It was a Sunday and the two boys were there. I have never seen such attractive kids in my life, and Charlie is positively fascinated by them. They are terribly fond of Paulette and in her shorts she looks like a little girl and the boys look upon her as a sister and expect her to come out and play with them. I am afraid they have the adventurous spirit of one Sydney Chaplin.

When I was there they were on the roof of the house, exploring the innermost parts under the roof. Young Syd is turning out to be an artist and Charlie is a musician. Daddy Charlie gave Charlie Jr his first accordion on which he has been practising and he does quite well; and it would have made you very happy to see Daddy Charlie playing the accordion and young Charlie’s expression totally fascinated by his daddy’s movements over the notes and of course the minor tones that Charlie drags out of that instrument. You would be happy to see your namesake. They are lovely boys and I was terribly thrilled because it was the first time I had the opportunity of seeing Charlie au famille.

We had a regular English Tea with muffins and crumpets and cake and to make it thoroughly English, Paulette had a little drop of rum in her tea. I missed both you and Minnie. With you it would have made one grand happy family.13

Charlie Junior remembered this Sunday tea (with marmalade on the crumpets) as an unchanging ritual. ‘“It’s four o’clock, boys,” he [their father] would religiously inform us on the weekends we spent with him. “Time for tea and crumpets as it’s done in England just at this hour.”’

That spring of 1933 Chaplin acquired a new toy, which was to provide him with therapeutic recreation for years. Disregarding financial stringencies, he ordered from Chris-Craft a 1932 model 38-foot commuting cruiser, with an 8-cylinder, 250 h.p. motor and a speed of 26 knots. It slept four, would ride twenty people, and had a one-man crew – Andy Anderson, a one-time Keystone Kop. It had a luxurious cabin, galley and dining quarters and, provided with bedding, linen, stove, refrigerator and cooking utensils, cost $13,950 from the Michigan factory. Sydney, between his usual advice about contracts and investments, wrote to Alf Reeves:

I hear he has bought a yacht. Tom Harrington sent me a photograph of it. It is certainly a good looking boat, and he must be having a great time. It is a good place to concentrate on a story, provided he has not too many distractions aboard.14

For the first few weeks, of course, the boat was nothing but distraction. On 25 March the two boys were taken to Wilmington to see it for the first time; after that Chaplin and Paulette spent every free moment on it, with trips to Catalina, Santa Cruz and Santa Barbara. Chaplin called the boat Panacea. Sydney was right that a boat was a good place for writing: almost as soon as he had acquired it, Chaplin set to work on the scenario that was to become Modern Times.

It was in the 1930s that Chaplin’s critics – often the best-disposed of them – began to complain that he was getting above his station. The clown was setting himself up as a philosopher and statesman. He had mingled so much with world leaders (they said) that he had begun to think of himself as one. They regretted the lost, innocent purity of the old slapstick and shook their heads at the arrogance, conceit and self-importance of the man. If this had been true, it would have been less surprising than that Chaplin had remained as human and as conscious of reality as he did. No one before or since had ever had such a burden of idolatry thrust upon him. It was not he or his critics, but the crowds that mobbed him everywhere on his world tour that cast him in the role of symbol of all the little men of the world. To survive this, still sane and human, was something of a miracle. Chaplin felt the burden and the responsibility deeply. In a sudden outburst, in 1931, he told Thomas Burke:

But, Tommy, isn’t it pathetic, isn’t it awful that these people should hang around me and shout ‘God bless you Charlie!’ and want to touch my overcoat, and laugh and even shed tears. I’ve seen ’em do that – if they can touch my hand. And why? Why? Simply because I cheered ’em up. God, Tommy, what kind of a filthy world is this – that makes people lead such wretched lives that if anybody makes ’em laugh they want to kneel down and touch his overcoat, as though he was Jesus Christ raising ’em from the dead. There’s a comment on life. There’s a pretty world to live in. When those crowds come round me like that – sweet as it is to me personally – it makes me sick spiritually, because I know what’s behind it. Such drabness, such ugliness, such utter misery, that simply because someone makes ’em laugh and helps ’em to forget, they ask God to bless him.15

Burke felt that Chaplin had failed to understand. It was not the world that was wrong:

It’s Charlie himself. He asks too much. If only he could be as tolerant as ‘Charlie’ he would be happier. A little melting of that icy detachment; a little something that helped him see the world clearly as a world, instead of through his own temperament, a view of that world as a place not entirely given over to the breaking of the noble and the beautiful, and he would come to that understanding by which men as acutely sensitive as himself manage to live happily in this pigsty. Much of the trouble in his private life, and he has had a lot, has arisen from this very lack of patience with human nature. With a wide experience of life, he seems not to have profited by it. He knows people and is a quick judge of character, but he cannot adjust his ideals to meet them. He has intellectual perception, but it is unwarmed by the rays of tolerance, and is therefore sterile. But whatever he is, generous, cold, capricious, he calls out all my affection as a man and all my admiration as an artist … 16

If, from time to time, Chaplin felt impelled to set down his views on the state of the world and the path it should take, it was not from any overweening self-importance, but because he felt it was somehow his due to those billions who had appointed him their idol and their symbolic representative. He was a reasoning, reading, pensive man. He was realistically aware of his ability to gain a swift, superficial understanding of practically any subject. As a man in command of considerable personal wealth, he was particularly fascinated by economics. He had read Major H. Douglas’s Social Credit and was so impressed by its theory of the direct relationship of unemployment to failure of profit and capital, that – taking warning from growing unemployment in the United States – he had in 1928 turned his stocks and bonds into liquid capital, and so been spared at the time of the Wall Street crash. Douglas’s theory was enshrined in the opinions Chaplin gave forth to Flora Merrill of the New York World when she interviewed him in New York in February 1931, on the first stage of his world tour:

If America is to have sustained prosperity, the American people must have sustained ability to spend. If we continue to view the present condition as inevitable, the whole structure of our civilization may crumble. The present deplorable conditions certainly cannot be charged against the five million men out of work, ready to work, anxious to work, and yet unable to get jobs. If capital represents the genius of America it would seem obvious that for its own sake the present conditions should not continue or ever again be repeated. While crossing the continent I have been talking to all sorts of men – railroad men, workers, fellow travellers – and I heard that times are even harder than before the end of the old year. The country is talking about Prohibition which, as Will Rogers says, you cannot feed to the hungry. Unemployment is the vital question, not Prohibition. Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy and throw it out of work.

Labor-saving devices and other modern inventions were not really made for profit, but to help humanity in the pursuit of happiness. If there is to be any hope for the future it seems to me that there must be some radical change to cope with these conditions. Some people who are sitting comfortable do not want the present state of affairs changed. This is hardly the way to stave off bolshevistic or communistic ideas which may become prevalent.

Something is wrong. Things have been badly managed when five million men are out of work in the richest country in the world. I don’t think you can dismiss this very shocking fact with the old-time argument that these are the inevitable hard times which are the reaction of prosperity. Nor do I think the present economic conditions should be blamed on current events. I personally doubt it. I think there is something wrong with our methods of production and systems of credit. Of course I speak as a layman, like many thousands of others who are anxious at this very serious state of affairs.

I am not in a position to go into world economics, but it seems to me that the question is not whether the country is wet or dry, but whether the country is starved or fed. Also, it doesn’t seem to me that there is any doubt but that a shorter working day would take care of the unemployed. Mr Ford has urged for shorter hours for labor and innovations in our credit system. I think such changes might avert serious future national catastrophes.

Miss Merrill asked him what changes he most wanted to see. He replied:

Shorter hours for the working man, and a minimum wage for both skilled and unskilled labor, which will guarantee every man over the age of twenty-one a salary that will enable him to live decently.

Chaplin spent the whole of the first week after his return home working on the ‘Economic Solution’ he had begun in Japan. As it finally emerged, it was an ingenious scheme to promote the movement of money in Europe and to keep purchasing power abreast of production potential. It involved creating a new international currency, in which the former Allies would pay themselves the money owed them in war reparations but which Germany was not in a position to pay. Each of the Allies would put up a bond to guarantee the currency. ‘It only remains for the Allies to ratify this currency as having the value of gold, and it shall have the value of gold.’ Whether Chaplin’s Economic Solution could ever have been practical or not, it serves to illustrate the range and ingenuity of his intellectual effort. In political terms it probably represents capitalist utopianism rather than the socialism with which he was so regularly charged. Chaplin was full of enthusiasm for Roosevelt (who like himself was accused of dangerous socialist ideas) and the New Deal. He was delighted to make a broadcast on 23 October 1933 on station KHJ of the Columbia Broadcasting System in support of the National Recovery Act.

Undoubtedly these concerns and preoccupations underlay Chaplin’s thinking on Modern Times, but it was not his concern then or at any other time to make a didactic or satirical film – a fact which, unreasonably perhaps, disappointed some critics of the picture. He told Miss Merrill in her February 1931 interview:

I leave humanity to humanity. Achievement is more than propaganda. I am always suspicious of a picture with a message. Don’t say that I’m a propagandist. The world at the moment is in such a turmoil of change that there are no signs of stability anywhere on which to speculate sensibly concerning the future, but I am sure it will be a good enough world to want to live in for a while. I want to live for ever. I find that life is very interesting, not from the point of view of success but from the changing conditions, if only people would meet them and accept them and go along with them. It is so much better to go with the change, I think, than to go against. As I grow older I find it is better to go with the tide.

Modern Times is an emotional response, based always in comedy, to the circumstances of the times. In the Keystone and Essanay films the Tramp was knocked around in a pre-war society of underprivilege, among the other immigrants and vagrants and petty miscreants. In Modern Times, he is one of the millions coping with poverty, unemployment, strikes and strike-breakers, and the tyranny of the machine.

A remarkable and revealing note by Chaplin on the characterization in Modern Times shows that he did not intend the Tramp and the Waif – ‘the Gamin’ as she was consistently called, though in later years Chaplin was inclined to correct this to ‘Gamine’ – as either rebels or victims. They were rather spiritual escapees from a world in which he saw no other hope:

The only two live spirits in a world of automatons. They really live. Both have an eternal spirit of youth and are absolutely unmoral.

Alive because we are children with no sense of responsibility, whereas the rest of humanity is weighted down with duty.

There is no romance in the relationship, really two playmates – partners in crime, comrades, babes in the woods.

We beg, borrow or steal for a living. Two joyous spirits living by their wits.17

The Tramp, then, is finally a self-confessed anarchist.

Modern Times does not have the integrated and organic structure of Chaplin’s previous features. The critic Otis Ferguson, not unjustly, said that it was really a collection of two-reelers which might have been called The Shop, The Jailbird, The Watchman and The Singing Waiter. The unifying theme is the battle for survival, ultimately a joint battle waged by the two main characters. The scenes of the Gamin’s troubles before her meeting with the Tramp are among the very rare instances in Chaplin’s films (another is Edna’s scenes in The Kid) where there is an independent secondary and parallel line of action running alongside the narrative of the Tramp’s misadventures.

The finished film opens with a symbolic juxtaposition of shots of sheep being herded and workers streaming out of a factory. Charlie is seen at work on a factory conveyor belt. He is caught up in the cogs of a giant machine, is used as guinea pig for an automatic feeder, and finally runs amok. Released from the mental hospital, he quickly lands in prison on a charge of being a Red agitator (he has merely picked up a red flag that has fallen off a lorry). After he inadvertently prevents a jail-break, life in prison becomes so pleasant that he is heartbroken to be pardoned. He does his best to get arrested again, but changes his mind after he meets the Gamin, a gutsy little orphan on the run from the juvenile officers. They set up home together in a waterfront shack, where Charlie sleeps in the doghouse outside.

Now that he values freedom, Charlie is soon sent back to prison after some of his former prison friends burgle the department store where he works as night-watchman. On his release, he finds the Gamin working as a dancer in a low cabaret, where she finds him a job as a singing waiter. Called upon to substitute for the romantic tenor, Charlie writes the words on his cuffs, which inconveniently fly off at his first dramatic gesture. He retrieves the situation by performing the song in a make-believe jabber-wock language. Before he can take his bow, however, the juvenile officers arrive to carry off the Gamin. The pair make a quick escape. On a country road, they jerk themselves out of their dejection. ‘We’ll get along,’ says the sub-title. Arm in arm they saunter off towards the horizon.

As usual, Chaplin’s ideas went through many metamorphoses and permutations before the story took its final shape. An early series of notes suggests a possible opening:

Large city – early morning rush of commerce – showing subway street traffic – newspaper printing office – factory whistles – ferry boats – ambulance, fire engine – motor traffic – introducing a comedian in complete contrast – calm, nothing to do – business crossing the road – klaxon – policeman belching – mistaken for klaxon – stick business and grating outside store window – search for work – different jobs and fired from each …

It is interesting to find the stick business cut from City Lights resurfacing here; later the notes also suggest, ‘work the twin fighter gag in a café’. Chaplin never wasted anything. There are suggestions for nice ironic gags which did not reach the finished film. The factory boss, nursing his ulcers on clear soup, crackers and pills, looks out of his window and sees his workers gobbling huge lunches while listening to an agitator lamenting that the poor working man must starve while the bosses live on the fat of the land. The infuriated boss empties his soup out of the window onto the orator’s head. Two tramps on a park bench solemnly discuss the world crisis and their fears of going off the gold standard: ‘This means the end of our prosperity – we shall have to economize.’ They replace their cigarette butts in their tins and one puts his lighted match into his pocket. The tone is ribald:

Second tramp: ‘Are you carrying anything?’ First tramp: ‘Yes, I am loaded up with consolidated gas but I am afraid I shall have to let it go.’ Second tramp, gives him look of concern: ‘I would try and hold onto it for a while if I were you.’

Another idea is for a factory where heavy machinery is developed for such trivial tasks as cracking nuts or knocking the ash off cigars. After this, the story takes off on a quite different tack as the Tramp or tramps stow away on a ship and land up in a series of Crusoe-like adventures on a tropical island – adventures evidently inspired as much by the possibility of parodying King Kong and Tarzan as by Chaplin’s own recent sightseeing in the Orient.

Alf Reeves, who rarely sought to make a contribution to the creative side of the studio work, was this time responsible for a very good idea, similar to one used much later by Woody Allen in Sleeper (1973). Charlie would find his way into the locked room where the factory’s management are experimenting with a robot which can fly an aircraft. Surprised by the bosses, Charlie is obliged to disguise himself as the robot, and must then go through the robot’s actions, including flying the plane. ‘If more thrills were required,’ wrote Reeves enthusiastically in his memorandum, ‘it could be worked up with the effects mechanism they use now and it should be an incident which could be worked up for a big gag.’ The suggestion was never taken up, however.

Chaplin was always rejecting and refining his ideas, and at the next stage wrote out a list of the gag suggestions he now felt were germane to the story:

Stomach rumbling

Steam shovel

Kidnapping

City environment

Museum and public gallery

Dry goods store

Street fair

Docks

Dives

Cabarets

Band parade

Street fire

Police raid

Street riots

Strikes

Telephone wire repairing

Dock working

Baggage staircase

Labor exchange

Bread line …

The earliest scenario draft which is clearly identifiable as the prototype for Modern Times has the title Commonwealth. The episodes are more numerous and less closely linked than in the finished film, although the relationship of Charlie and the Gamin and the general progression in search of work are already defined. Some incidents of the finished film are already present: the red flag, the accidental launch of a liner, the jailbreak, Charlie’s efforts to get himself arrested, the meeting with the Gamin in the police wagon and subsequent escape. The factory is in part developed, with a world of push-button gadgets for the boss’s use. Charlie’s conveyor-belt mental breakdown is now the motive for pathos.

Among the sequences that were to be rejected was a long scene of slapstick action when Charlie pretends he is a qualified steam shovel operator in order to get a job. In another sequence Charlie and the Gamin take shelter in an empty house, unaware that it is in the process of being demolished. Chaplin’s politico-economic preoccupations surface in a scene in which Charlie and the girl are punished for eating eggs which are being dumped in the sea as surplus. There is an echo of The Kid in one of their ruses to make a little money: the Gamin steals purses and wallets, which Charlie then politely returns hoping for (but not demanding) a reward from the grateful owners. The café sequence in this draft is very different: it is Charlie who first gets a job as waiter, and in turn gets a place for the girl – in blissful ignorance that the place is also used as a bawdy house.

The major divergence from the initial sketch, however, is the ending of the film. At this stage Chaplin was evidently looking for something to surpass City Lights in pathos. Following a breakdown brought on by the strain of non-stop tightening of nuts on the conveyor belt, Charlie is put in hospital. As he is recuperating, he is told he has a visitor: it is the Gamin, who has become a nun. They part with sad smiles.

The ‘nun’ ending was fully elaborated in the production notes:

The full moon has changed to a crescent, and from a crescent to a full moon again.

The scene changes to the hospital. Fully recovered, the Tramp, who is about to be discharged, is informed that a visitor is waiting to see him in the reception room. He makes his way, laboriously, towards it. When he arrives there, to his surprise, he finds the Gamin, attired as a nun. She is standing, and beside her is a Mother Superior. The Gamin greets him, smiling wistfully. The Tramp looks bewildered. Somehow a barrier has risen up between them.

He tries to speak but can say nothing. Smiling sympathetically, she takes his hand. ‘You have been very ill,’ she says, ‘and now you are going out into the world again. Do take care of yourself, and remember I shall always like to hear from you.’ He tries to speak again but, with a gesture, gives it up. As she smiles, tears well up in her eyes while she holds his hand and he becomes embarrassed; then she stands as a final gesture that they must part.

The Mother Superior leads them to the door and at the entrance of the hospital she says her last ‘goodbye’, while the Mother Superior waits in the reception room. He releases his hand and walks slowly down the hospital steps, she gazing after him. He turns and waves a last farewell and goes towards the city’s skyline. She stands immobile – watching him as he fades away.

There is something inscrutable in her expression, something of resignation and regret. She stands as though lost in a dream, watching after him and her spirit goes with him, for out of herself the ghost of the Gamin appears and runs rampant down the hospital steps, dancing and bounding after him, calling and beckoning as she runs toward him. Along that lonely road she catches up to him, dancing and circling around him, but he does not see her, he walks alone.

She is standing on the hospital steps. She is awakened from her revelry [reverie?] by a light touch, the hand of the Mother Superior. She starts, then turns and smiles wistfully at the kindly old face and together they depart into the portals of the hospital again. FADE OUT

During the year that the story was in preparation, life went on practically without incident. At the studio the stages were repaired and made ready for the moment that Chaplin chose to start production, and a bathroom was added to the dressing room that was to be Paulette’s. In September 1933, Carter De Haven was taken on to the staff, to be a general assistant to Chaplin, and in particular to help with the story. At the beginning of January 1934, Henry Bergman was put back on the payroll. De Haven and Henry sat in on most of Chaplin’s script sessions. Chaplin had decided to keep the eventual title of the film secret. In November 1933, a sealed envelope containing the title was sent by registered mail to Will H. Hays, President of the Motion Picture Producers’ and Distributors’ Association in New York, with instructions not to open it but to register the unknown title as of 11 November 1933, and to place the envelope in safekeeping until publication should be announced.

At the house, too, life followed a routine, with trips on the boat when the weather was good and regular outings or visits for the boys. In April their father took them to the circus, and they were thrilled to be photographed with Poodles Hannaford and Chaplin’s old Keystone colleague, Charlie Murray. Chaplin went to a party and to a drill demonstration at the Black-Foxe Military Academy, where the boys had been enrolled. Charles Junior remembered ‘that I marched straighter, that I was more alert, that I saluted with a snappier gesture and clicked my heels more sharply when I saw those ice-blue eyes upon me’.18

There was one major domestic upheaval during this period. Kono, who had served Chaplin with discreet devotion for eighteen years, first as chauffeur, later as private secretary and major-domo, announced his intention of leaving. Paulette was not content to be a guest at Summit Drive, as Mildred and Lita had been, and as she gave more and more attention to the running of the house, Kono felt he was being gradually usurped. Chaplin and Paulette both sought to allay his fears, but he was adamant, and resigned. Chaplin was distressed but arranged a job for Kono with the United Artists exchange in Tokyo, and sent him and his wife on their way with a present of $10,000. Kono found no consolation in his new job and had no better success when, his United Artists contract having run out, he tried distributing the Chaplin films in Japan. He returned to California but never rejoined the Chaplin staff.

By the end of August 1934 Chaplin was satisfied with his story. According to the studio records, he spent a week or so at Lake Arrowhead with De Haven, Bergman and Miss Steele, the secretary, ‘to put story into script form’. If there ever was a script in conventional form, however, no copy has survived; this reference may be to a dialogue script, which will be discussed subsequently. Throughout September and the early part of October the studio went into full operation. Charles D. (Danny) Hall had been preparing sketches for some time, and his construction crew now set about building the factory interiors in the studio. The films had outgrown the old studio street, and four acres of land at Wilmington were rented on which to build a big street set. The Chaplin Studio was one of the last in Hollywood to retain a stage open to the sky, and preparations were finally begun to enclose it and bring it up to modern, sound-era standards. On 4 September, Paulette signed her contract. On 20 September, Alf Reeves wrote to Sydney:

Looks like shooting next week. Some factory interiors are being built on the stage, and he has found some splendid locations. In view of the fact that he has practically eliminated the worry during production of thinking out his story, he expects to have the picture finished by January. However, this, as you know, is not definite.19

Alf’s doubts about the January finish were reasonable and justified: the final shot of the picture was not taken until 30 August 1935. Even so, the shooting period of ten and a half months was the shortest for a Chaplin film since A Woman of Paris.

Shooting finally began on 11 October with a scene in the office of the factory boss, played by Allan Garcia. The next sequence was set in the dynamo room, and on 15 October the unit worked through the night from 7.30 p.m. to 4.45 a.m. With hindsight, this seemed prescient because the following evening, just as they were coming to the end of work on the sequence, a heavy rainstorm penetrated the tarpaulins laid over the set on the still-open stage and severely damaged it.

The rest of the factory scenes were shot in six weeks, uninterrupted except for a day in December when Douglas Fairbanks brought Lady Edwina Mountbatten and her party to visit the set. Working hours now tended to be longer than in ‘silent’ days, when frequently no shooting began before lunch. Now Chaplin was generally at the studio by 10.30, although on days when he was acting alone he still preferred a shorter, afternoon session of work, perhaps to avoid exhaustion.

Even at this stage Chaplin remained undecided about sound. In public statements on the matter he was unequivocal. Early in 1931 he had made several statements to the press: ‘I give the talkies six months more. At the most a year. Then they’re done.’ Three months later, in May 1931, he had slightly modified his opinion: ‘Dialogue may or may not have a place in comedy … What I merely said was that dialogue does not have a place in the sort of comedies I make … For myself I know that I cannot use dialogue.’ The interviewer asked him if he had tried:

I never tried jumping off the monument in Trafalgar Square, but I have a definite idea that it would be unhealthful … For years I have specialized in one type of comedy – strictly pantomime. I have measured it, gauged it, studied. I have been able to establish exact principles to govern its reactions on audiences. It has a certain pace and tempo. Dialogue, to my way of thinking, always slows action, because action must wait upon words.

However firm his public statements on the issue, in the privacy of his studio Chaplin was clearly less convinced. At the end of November he and Paulette did sound tests: since both had pleasant voices which recorded well, it is unlikely Chaplin was dissatisfied with them. It is now clear that Chaplin at this time had steeled himself to shoot the film, including his own scenes, with dialogue. A dialogue script was prepared for all scenes up to and including the department store sequence, and still survives.

The dialogue which Chaplin gave to the Tramp is staccato, quippy, touched with nonsense; in the Dream House fantasy sequence it is remarkably similar to the cross-talk act between Calvero (Chaplin) and Terry (Claire Bloom), as Tramp and Pretty Girl, in Calvero’s dream in Limelight.

Gamin: What’s your name?

Tramp: Me? oh, mine’s a silly name. You wouldn’t like it. It begins with an ‘X’.

Gamin: Begins with an ‘X’?

Tramp: See if you can guess.

Gamin: Not eczema?

Tramp: Oh, worse than that – just call me Charlie.

Gamin: Charlie! There’s no ‘X’ in that!

Tramp: No – oh, well, where d’ya live?

Gamin: No place – here – there – anywhere.

Tramp: Anywhere? That’s near where I live.

The first dialogue which Chaplin began to rehearse was for the scenes in the jail and the warden’s office. Much of the dialogue was concerned with confusions over the name of the curate and his wife – Stumbleglutz, Stumblerutz, Glumblestutz, Rumbleglutz, Stumblestutz and, as the inevitable climax, Grumblegutz. Chaplin was apparently deeply dissatisfied with the results. The unit had been told that the Dream House sequence would be shot the following day with sound. In fact, no more dialogue scenes were shot for Modern Times.

Chaplin did proceed with sound effects, however, and used the recording apparatus set up to create the stomach rumbles for the scene. He created the noise himself by blowing bubbles into a pail of water. As Totheroh warned him, the noises were much too explosive; eventually they were reshot. The fact that Chaplin was sufficiently keen to create the effects himself suggests the extent to which he was intrigued by sound problems at this time. A memorandum about possible musical effects notes: ‘Natural sounds part of composition, i.e. Auto horns, sirens, and cowbells worked into the music.’

Chester Conklin, who had worked with Chaplin so many times since Making a Living, was engaged for three weeks’ work as the walrus-moustached old workman who gets caught up in the cog wheels of a gigantic machine of doubtful purpose. When he becomes completely stuck, Charlie considerately feeds lunch to his protruding head. Two other reliable old allies from two-reeler days – an escalator and an old Keystone colleague, Hank Mann – were introduced into the department store scenes, which, including retakes, took five weeks to shoot. Eight working days of this time were taken up by Chaplin’s brilliant roller-skating routine: the skating was quickly shot, but time was needed to prepare the trick ‘glass shots’ to give the illusion that he was skating at the edge of a high balcony with no balustrade.

Chaplin was still intent on ending the film with the Gamin as a nun. The sentiment was perilous, but he had attempted perilous things before: the ending of City Lights, seen only on paper, could look like mere kitsch. He also planned to prepare the way for the ending with a recurrent theme of a kindly nun, and her effect upon the Gamin.

THEME

1. On one of our adventures we come into contact with a nun. It’s just a momentary feeling or sense of beauty and the Gamin is moved by it.

Gamin: ‘She makes me want to cry.’

The nun is always very tender and nice to the Gamin – a pat on the head, etc.

2. We encounter her in the street again. The Gamin imitates her headgear and admires it. Each time the Gamin sees her she stops short in the midst of the comedy and her eyes fill and she says:

Gamin: ‘She makes me feel wicked.’

3. We are in the street and the Gamin has just pinched something. The nun comes around the corner and the Gamin puts it back.

Charlot: ‘What in blazes is wrong with you?’

Gamin: (Gulp) I dunno.’

(The use of the name ‘Charlot’ is an odd, distinctive feature of the voluminous working notes on Modern Times. The Tramp character is throughout variously referred to as ‘Charlie’ or ‘Charlot’ – the French name for Chaplin. Elsewhere in the notes Chaplin, exceptionally, refers to his character in the first person, styling Tramp and Gamin as ‘We’.)

The nun sequence was shot in late May and early June. On Friday, 25 July 1935 Chaplin and his assistants ran the film and, noted the studio secretary at the time, discussed a new ending. No one concerned has left any account of the discussion, so we shall never know if the decision to change was spontaneously Chaplin’s or whether, as sometimes happened, he made his judgement after watching the reactions of his colleagues. Whatever the temper of the meeting, Chaplin went off on his yacht the following day for the weekend.

The final sequence to be shot was the café scene. This took twelve days and involved a large number of extras: 250 were called for the day when Chaplin shot the sequence of carrying a roast duck across the jam-packed dance floor. This was to be the historic scene in which the Tramp, for the first and only time, found his voice on the screen. When the Tramp opened his mouth and sang, it was in a language of his own invention, expressive of everything and nothing:

Se bella piu satore, je notre so catore,

Je notre qui cavore, je la qu’, la qui, la quai!

La spinash or le busho, cigaretto toto bello,

Ce rakish spagoletto, si la tu, la tu, la tua!

Senora pelafima, voulez-vous le taximeter,

La zionta sur le tita, tu le tu le tu le wa!

and so on, for several more verses. The accompanying pantomime elaborates a tale of a seducer and a coyly yielding maiden.

At some point during late July or early August, the decision was finally taken to change the ending. The last shots taken on the café set, on 20 August, were those involving the detectives who arrive at the café to take the Gamin away. Since this action, and the subsequent getaway of Charlie and the Gamin, provide the link with the present ending of the film, the tempting assumption is that the decision was made during the shooting of these scenes.

The last retakes were made on 30 August, and after the Labour Day holiday Chaplin began cutting. On 10 September, the film was in a sufficiently assembled form for Chaplin to run it for two of his most valued critics, Charles Junior and Sydney Junior, who had just arrived back after three months with their mother in New York. At ten years old, Charles Junior observed with astonishment the extent of the physical and emotional strain to which his father submitted himself in the course of making a picture. After the day’s work, during which he would astound and irritate his staff with his apparent inexhaustibility, he would arrive home, still in make-up and costume, already half asleep and so tired that he had to be helped from his car. The exhaustion, young Charles remembered years later, was worse when the day had not gone well. Chaplin’s therapy for his weariness was in itself punishing. He would shut himself in his steam room for three-quarters of an hour, after which he might well emerge sufficiently restored to go out for dinner. Sometimes, though, he would simply retire to bed for the evening, and have his meal sent up.

In the last stages of shooting Modern Times he had worked with such concentration that he had actually lived at the studio, and brought with him George, the Japanese cook, to see to his meals. Paulette, like Chaplin’s previous partners, discovered that at such critical times Chaplin’s work left no room for personal life, even his most precious relationships. More easily than the previous women in his life, she was able to acknowledge this insuperable rival. When she was seen around the town without Chaplin, however, there was speculation about a break-up; though what was to be broken up was unclear, since Chaplin and Paulette, with admirable disdain for the gossips, refused to clarify their marital or non-marital status merely to satisfy other people’s curiosity.

Work on the music began in August 1935. Alfred Newman, whose collaboration on City Lights had given Chaplin great satisfaction, was again to be musical director, and Edward Powell was engaged as orchestrator. Powell wired to the East Coast to invite a talented young colleague from his days with the music publishers Harms, David Raksin, to join him. Raksin, who has vividly and sensitively recorded his impressions of working with Chaplin,20 recalls that Powell’s telegram arrived on 8 August 1935, four days after his twenty-third birthday. Chaplin, having been promised a musician who was ‘brilliant, experienced, a composer, orchestrator and arranger with several big shows in his arranging cap’, confided that he was somewhat disconcerted when ‘this infant shows up’. Raksin, for his part, was captivated by Chaplin, loved Modern Times and laughed at it so hard that Chaplin for a time wondered whether he was exaggerating for his benefit. After only a week and a half, however, Raksin was summarily fired:

Like many self-made autocrats, Chaplin demanded unquestioning obedience from his associates; years of instant deference to his point of view had persuaded him that it was the only one that mattered. And he seemed unable, or unwilling, to understand the paradox that this imposition of will over his studio had been achieved in a manner akin to that which he professed to deplore in Modern Times. I, on the other hand, have never accepted the notion that it is my job merely to echo the ideas of those who employ me; and I had no fear of opposing him when necessary, because I believed he would recognize the value of an independent mind close at hand.

When I think of it now, it strikes me as appallingly arrogant to have argued with a man like Chaplin about the appropriateness of the thematic material he proposed to use in his own picture. But the problem was real. There is a specific kind of genius that traces its ancestry back to the magpie family, and Charlie was one of those. He had accumulated a veritable attic full of memories and scraps of ideas, which he converted to his own purposes with great style and individuality. This can be perceived in the subject matter, as well as the execution of his story lines and sequences. In the area of music, the influence of the English music hall was very strong, and since I felt that nothing but the best would do for this remarkable film, when I thought his approach was a bit vulgar, I would say ‘I think we can do better than that.’ To Charlie this was insubordination, pure and simple – and the culprit had to go.21

Raksin was heartbroken, but Newman told him, ‘I’ve been looking at your sketches, and they’re marvellous – what you’re doing with Charlie’s little tunes. He’d be crazy to fire you.’ As Raksin was packing to leave, Alf Reeves called him and asked him to come back. Raksin agreed, after first explaining to Chaplin that he could always hire a musical secretary if that was what he wanted, ‘but if he needed someone who loved his picture and was prepared to risk getting fired every day to make sure that the music was as good as it could possibly be, then I would love to work with him again’. This was the beginning of ‘four and a half months of work and some of the happiest days of my life’.

Raksin feels that previous commentators have given at once too much and too little credit to Chaplin’s musical abilities.

Charlie and I worked hand in hand. Sometimes the initial phrases were several phrases long, and sometimes they consisted of only a few notes, which Charlie would whistle, or hum, or pick out on the piano … I remained in the projection room, where Charlie and I worked together to extend and develop the musical ideas to fit what was on the screen. When you have only a few notes or a short phrase with which to cover a scene of some length, there must ensue considerable development and variation – what is called for is the application of the techniques of composition to shape and extend the themes to the desired proportions. (That so few people understand this, even those who may otherwise be well informed, makes possible the common delusion that composing consists of getting some kind of microflash of an idea, and that the rest of it is mere artisanry; it is this misconception that has enabled a whole generation of hummers and strummers to masquerade as composers.)

Theodore Huff and others to the contrary, no informed person has claimed that Charlie had any of the essential techniques. But neither did he feed me a little tune and say, ‘You take it from there.’ On the contrary: we spent hours, days, months in that projection room running scenes and bits of action over and over, and we had a marvellous time shaping the music until it was exactly the way we wanted it. By the time we were through with a sequence we had run it so often that we were certain the music was in perfect sync. Very few composers work this way … the usual procedure is to work from timing sheets, with a stop clock, to coordinate image and music …

Chaplin had picked up an assortment of tricks of our trade and some of the jargon and took pleasure in telling me that some phrase should be played ‘vrubato’, which I embraced as a real improvement upon the intended Italian word, which was much the poorer for having been deprived of the v. Yet, very little escaped his eye or ear, and he had suggestions not only about themes and their appropriateness, but also about the way in which the music should develop …

Sometimes in the course of our work, when the need for a new piece of thematic material arose, Charlie might say, ‘A bit of “Gershwin” might be nice there.’ He meant that the Gershwin style would be appropriate for that scene. And indeed there is one phrase that makes a very clear genuflection toward one of the themes in Rhapsody in Blue. Another instance would be the tune that later became a pop song called ‘Smile’. Here, Charlie said something like, ‘What we need here is one of those “Puccini” melodies.’ Listen to the result, and you will hear that although the notes are not Puccini’s, the style and feeling are.22

The ten-year-old Charles Chaplin Junior observed that ‘if the people in his own studio had suffered from Dad’s perfectionist drive, the musicians … endured pure torture.’

Dad wore them all out. Edward Powell concentrated so hard writing the music down that he almost lost his eyesight and had to go to a specialist to save it. David Raksin, working an average of twenty hours a day, lost twenty-five pounds and sometimes was so exhausted that he couldn’t find strength to go home but would sleep on the studio floor. Al Newman saw him one day in the studio street walking along with tears running down his cheeks.23

Chaplin would work with Raksin on the transcription of his compositions night after night until long after midnight, and did not even spare him at the weekends, though on one of these there was the consolation of working on the Panacea while Paulette took the children to Palm Springs to keep them out of their busy father’s way. Raksin recalls not only the killing round-the-clock work, but also the gags and jokes and high spirits. Unfortunately it was to end unhappily. Newman liked to work in the small hours of the night. At one of these nocturnal sessions on 4 December, when Raksin was taking a night off at Chaplin’s suggestion, Chaplin and the volatile Newman had a fierce argument. After a bad take, Chaplin accused the musicians of ‘dogging it’ (lying down on the job). Newman exploded, hurled his baton across the studio, addressed a string of curses to Chaplin and stalked off to his suite to revive himself with a whiskey before calling Sam Goldwyn to tell him that on no account would he ever work with Chaplin again. Nor did he. From loyalty to Newman, Raksin would not take over the conducting, and the outcome was an estrangement from Chaplin that lasted for many years. Powell was coerced on the strength of his contract to conduct. ‘With Eddie conducting, I did most of the remaining orchestration, and the recordings concluded in a rather sad and indeterminate spirit,’ Raksin recalled. The music was finally completed on 22 December 1935. Years later the former cordiality between Chaplin and Raksin was revived: the musician last visited the studio the day before Chaplin’s final departure from America in 1952.

To add to his anxieties, Chaplin had a distinguished house guest. H. G. Wells had arrived in Hollywood on 27 November for a four-week stay; and the evening of the Newman row, he and Chaplin were guests of honour at a Motion Picture Academy dinner. With Paulette’s help, Wells was somehow entertained. Alf Reeves wrote to Sydney that he had not even seen the great man during his visit, because Chaplin only brought him to the studio at nights. With the music finished, however, his host at least had time to see Wells off on his flight back.

Chaplin finally previewed Modern Times, with great secrecy in advance of the official première screening, in San Francisco. Alf Reeves was able to report to Sydney the following day: ‘audience applauded “Titine” (and “encored” it!) and cheered at the end.’ Nevertheless Chaplin decided on a few cuts, and there were more after a second preview at the Alexander Theatre, Glendale. Generally the launch of the film was effected more quietly than that of City Lights. Modern Times opened at the Rivoli, New York, to capacity business, on 5 February 1936, and at the Tivoli, London, on 11 February. The West coast gala première at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood on 12 February was a comparatively modest event. Perhaps Chaplin was more confident this time. Certainly the public reaction was all he could have hoped for, although the press was mixed. One faction disapproved because he had attempted socio-political satire; another regretted that he had not, though he seemed to promise it with the opening title of the film: ‘The story of industry, of individual enterprise – humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness’.

The release of Modern Times was to spark three irritating incidents. The first was a plagiarism suit brought by a certain Michael Kustoff, a White Russian lawyer with a history of severe mental disorder. Kustoff had published a paranoiac autobiography about his experiences in mental hospitals (alleging, for instance, how poison gas had been pumped into his hospital room); and now claimed that there were one hundred correspondences between his book and Modern Times. The Kustoff case was quickly dismissed when it came to court on 18 November 1939.

Another plagiarism claim was to nag on for more than a decade, even though it never came to trial. On 26 May 1936, three months after the release of Modern Times, United Artists informed the Chaplin studio that the Franco-German production firm Tobis were claiming 1,200,000 francs in damages on account of alleged plagiarism of René Clair’s 1931 film, A Nous la Liberté. Chaplin, along with everyone else at the studio, claimed never even to have seen the film. It was resolved to approach Clair himself, who had consistently declared his admiration for Chaplin and his debt to his films. A deputation arranged by Alexander Korda and consisting of the exiled German producer Erich Pommer and Korda’s Hungarian associate Steve Pallos visited Clair, whose view of the affair was reported in Le Soir of 28 October 1936:

Chaplin is too great a man and I admire him too much to admit that his creative genius should be contested in any way. I, myself, owe him very much. And besides, if he has borrowed a few ideas from me, he has done me a great honour.

Nevertheless the Tobis lawyers persisted. On 3 July 1936, they demanded arbitration, and then in October withdrew the offer of arbitration and initiated parallel actions in France and the United States. On 4 August 1937, United Artists’ Paris office was served with the suit, alleging that Modern Times was a plagiarism of A Nous la Liberté in terms of idea, choice of scenes, incidents, rhythm, images and in general terms – ‘bondage of the factory, apparent idleness of the chief, the constant watch in the prison, in the factory, in private life, the departure on the road at random …’ Tobis demanded the banning of Modern Times in France, the confiscation of all negatives and positives, which should be handed over to the plaintiff, and a payment of one million francs in damages and interest. In addition, the plaintiffs claimed costs and the publication of the judgement, at the defendants’ expense, in twenty newspapers to be chosen by the plaintiff.

For all these ambitious demands, the Tobis case was extremely weak, and it is unlikely that any court would have found in their favour. Chaplin could easily show that his concern with the dehumanization of factory work went back to the 1920s. His choice of a conveyor belt as a comic prop looks back to the escalator in The Floorwalker. Tobis’s American lawyer, Milton Diamond, claimed he had proof that Chaplin had had a copy of A Nous la Liberté in his possession and had repeatedly viewed it in 1934 and 1935; but in the outcome the depositions taken from Diamond’s witnesses proved worse than shaky.

Chaplin needed a French legal representative. United Artists had engaged a Parisian lawyer, Maître Suzanne Blum (1899–1994), who was to become famous – even notorious – many years later as the Duchess of Windsor’s adviser, guarding her aged and ailing client from the world with the jealous ferocity of a dragon. She had so far handled United Artists’ case with exemplary aplomb and skill, but Chaplin’s current New York lawyer, Louis Frohlich, a partner in the firm of Schwartz and Frohlich, was conservative in such matters. ‘I do not like these so-called women lawyers,’ he wrote firmly to the studio.

In any event, it seemed preferable for Chaplin to have a different representative from the one acting for United Artists. Capriciously he decided upon the only Parisian lawyer known to him, whom he happened to have met by chance during his 1931 world tour. Chaplin felt that this man, Henry Torres, was particularly suited since he had a Jewish wife and so would feel a proper motivation to fight a company with German parentage. Suzanne Blum pointed out that, though Torres was a personal friend and a fine lawyer, his speciality was political cases and he had no experience in this kind of affair. The Chaplin studio and lawyers persisted. Suzanne Blum was required to brief Torres on every detail of the case: his fee was $2000; hers $750.

By this time, however, war had broken out in Europe. Torres, with his Jewish wife, fled to Latin America and was not heard of again. Suzanne Blum, who was also Jewish, quit occupied France and arrived in New York as a refugee, in acute need of money. When she requested her fee, however, Sydney Chaplin, on behalf of the studio, retorted that he saw no reason to pay her since the case had not been completed. The New York lawyers, clearly embarrassed, eventually succeeded in getting the studio grudgingly to agree to pay Madame Blum half of what she was owed.

With France occupied, it was decided to abandon any defence of the French case, and on 2 January 1941, Suzanne Blum and the absent Henry Torres were formally dismissed. On 21 January 1941, the American case was stayed and marked as dismissed for lack of evidence. In particular this referred to the impossibility of producing in court the President of Films Sonores (the new name of Films Tobis Sonores), M. Georges Loureau-Dessus, who had last been reported serving on the Maginot Line. However, on 9 March, Judge Mandelbaum reconsidered the matter and decreed that ‘In view of the war situation I am extending the plaintiff’s time to have its president Georges Loureau-Dessus examined before trial on or before March 5 1943. Either side may move for appropriate relief should the war end prior to that time.’ Of course the war did not end, and the American case, like the French one, lapsed.

At this point it might have been supposed the affair was at an end. But in May 1947, Films Sonores, with M. Georges Loureau-Dessus still its President, renewed its claim. By this time, though, United Artists and the Chaplin studio had had enough. After some bargaining over the price, Films Sonores agreed to drop all claims in consideration of a payment of $5000 in America and 2,500,000 francs (then approximately $25,000) in France. The deal was negotiated by none less than Maître Suzanne Blum, now back in Paris.

The obstinacy of Films Sonores remains puzzling. By the time that Modern Times was finished, four years had passed since the release of A Nous la Liberté, and five more years went by before there was even a prospect of a trial. Even if the plagiarism charges had been justified, Films Sonores could hardly claim that they had suffered a substantial financial loss to their film. Although René Clair was indignant at the suggestion that it was all part of a Nazi plot, the Chaplin Studio and United Artists remained convinced that, despite the change of name and a majority Dutch holding in the company, Films Sonores was still associated with the German firm Tobis, and that the harassment was stepped up when it was known that Chaplin was preparing The Great Dictator.

Happily, the affair seemed never to generate any personal animosity between Clair and Chaplin, although Clair himself liked to believe that Chaplin must in fact have seen his film. ‘There is no doubt in my mind about it. And I am very happy to be a modest creditor of a man towards whom we are all such considerable debtors,’ he told the critic Georges Sadoul.

A lesser irritation was an article which appeared in Pravda and was subsequently reported in the New York Times, in which Boris Shumyatsky, head of the Soviet state cinematography organization, claimed to have visited the Chaplin studio in the course of a journey to Hollywood, and to have persuaded Chaplin to change the ending of Modern Times to make it more ideologically acceptable. Curiously there is no trace of such a visit, either in the daily studio records, which were generally meticulous in noting visitors on set, or in the FBI files, which diligently maintained the record of all Chaplin’s Soviet links – even a visit to a film or a Shostakovich concert – and would certainly have been monitoring every move of so prominent a Russian as Shumyatsky.

Whether or not Shumyatsky’s account is true, it is understandable that he might write such an article. An ambitious and self-aggrandizing Stalinist bureaucrat – history remembers him for his hostility to Sergei Eisenstein, who was prevented from completing any film during Shumyatsky’s reign – his career was by this time becoming insecure (in 1939 he was to be liquidated by Stalin). What better assertion of his esteem and influence than to claim that he could coerce Hollywood’s and the world’s most famous film-maker into reshaping his film to suit the ‘socialist-realist’ canon?

The New York Times report irked the studio sufficiently for Alf Reeves to call a press conference in which he assured journalists that no one could ‘ever tell Chaplin about such matters. As you know he has very much his own way and his own ideas, always.’ Shumyatsky, he said, read ‘deep, terrible social meanings’ into sequences that were intended to be funny. Even the FBI did not take the teacup storm seriously, though latter-day apologists for the reactionary campaign against Chaplin have revived it as ‘proof’ that Chaplin was in thrall to Moscow.24

Private matters from time to time obtruded upon Chaplin’s concentration. The kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby was still very much in people’s minds in autumn 1934, and there were kidnap threats against the Chaplin children. Chaplin announced to the press that he had hired bodyguards and armed the house and studio. A few weeks earlier he had given his views on the possibility of his own kidnap. ‘Not one cent for ransom! I’ve given positive orders to my associates that under no condition is one cent to be paid anyone trying to extort money from me. If I should be kidnapped – and I’m not worrying any that it’s going to happen – I’d fight at the first opportunity. They’d either have to let me go or do murder.’

In April 1935, Minnie Chaplin became seriously ill in the South of France. She was operated upon but died shortly afterwards. The telegram of sympathy which Chaplin sent to his brother during Minnie’s last illness shows how even genuine fraternal concern could not supersede his preoccupation with work. He advises Sydney to be ‘philosophical’ and to ‘buck up’:

I HAVE BEEN WORKING HARD ON THE PICTURE WHICH WILL BE READY FOR FALL RELEASE AND FROM ALL INDICATIONS WE SHALL HAVE A SENSATIONAL SUCCESS STOP IN TREATMENT IT WILL BE SIMILAR TO CITY LIGHTS WITH SOUND EFFECTS AND AUDIBLE TITLES SPOKEN BY ONE PERSON HOWEVER WE ARE GOING TO EXPERIMENT WITH THIS IDEA STOP I INTEND TO WORK RIGHT ON AFTER FINISHING THIS PICTURE AS I FEEL I AM IN MY STRIDE AND INTEND TO MAKE HAY WHILE THE SUN SHINES STOP WHAT YOU NEED IS A CHANGE YOU SHOULD COME HERE WHERE YOUR ABILITY WOULD BE OF GREAT SERVICE AND VALUE STOP WHEN MINNIE GETS WELL YOU MIGHT CONSIDER COMING TO HOLLYWOOD IT WOULD DO YOU BOTH GOOD STOP.25

In the midst of his personal grief Sydney was no doubt both cheered and sceptical about Chaplin’s intentions to go straight back to work. Perhaps Chaplin had in mind a project which he had somehow found time to prepare during the whole production period of Modern Times – apparently the only time that he worked on a future feature project when he was already occupied with a film.

Chaplin commentators with a psychoanalytical bent have made much of his persistent ambition to play Napoleon. His interest is probably quite simply explained. Napoleon offers a uniquely rich role for an actor of small stature. Chaplin had been fascinated by the character ever since childhood, when his mother had told him that his father resembled the Emperor. In 1922, when looking for a vehicle to launch Edna Purviance as a dramatic actress (the eventual choice was A Woman of Paris), he had thought of a story to team the two of them as Napoleon and Josephine. When he first showed an interest in Lita Grey he spoke of creating the role of Josephine for her. Chaplin and Lita went to a fancy-dress party given by Marion Davies costumed as Napoleon and Josephine. Subsequently Lita began to worry when she found that he had in turn offered the role to Merna Kennedy. In 1926, much impressed by the Spanish singer Raquel Meller, Chaplin had spoken of working with her in a Napoleon film; but a year later the appearance of Abel Gance’s spectacular Napoleon temporarily discouraged him, even though it was shown in the United States only in a version cut by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer from the original six hours to little more than sixty minutes.