17

Limelight

Chaplin returned to California. Back home with Oona and the children he rapidly recovered from the ordeal of Monsieur Verdoux. He still had confidence in the American public’s affection and what’s more, ‘I had an idea and under its compulsion I did not give a damn what the outcome would be; the film had to be made.’1 Nor did he give a damn about Representative J. Parnell Thomas and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), or at least he was not going to allow them (as so many others in Hollywood did) to curb his opinions or his associations. ‘A democracy is a place where you can express your ideas freely – or it isn’t a democracy,’ he said. In the opinion of his son, Charles, ‘He always felt he belonged here in America, with its promise of freedom in thought and belief and its emphasis on the importance of the individual.’2 Some of his best friends in Hollywood felt that he should have shut up and not made unnecessary enemies, but Chaplin to his credit always valued his own feelings and the opinions of his friends more than he did those of his enemies. He made no secret of his support for the Liberal, Henry A. Wallace. His dinner guests included Harry Bridges, Paul Robeson and the ‘Red Dean’ of Canterbury, the Very Reverend Hewlett Johnson, whom he had met during his 1931 tour. In the late 1930s he had come to know Hanns Eisler, a refugee from Nazi Germany, and had remained friendly with him and his wife. Through the Eislers he also met Bertolt Brecht.

As early as December 1946, Ernie Adamson, chief counsel for the Un-American Activities Committee, announced that Chaplin was among the people who would be subpoenaed to testify at public hearings in Washington; but no more was heard of it at that time. In May 1947, Chaplin was again quizzed by the press about his unwillingness to take American citizenship, and again he gave the same answer: ‘I am an internationalist, not a nationalist, and that is why I do not take out citizenship.’ On 12 June, Chaplin became the subject of a heated debate in Congress. Representative John T. Rankin of Mississippi (who was also a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee) told the House:

I am here today demanding that Attorney-General Tom Clark institute proceedings to deport Charlie Chaplin. He has refused to become an American citizen. His very life in Hollywood is detrimental to the moral fabric of America. In that way he can be kept off the American screen, and his loathsome pictures can be kept from before the eyes of the American youth. He should be deported and gotten rid of at once.3

Chaplin was much more angered by an NBC broadcast given by Hy Gardner, and immediately filed a $3 million suit in the federal court, alleging that Gardner had defamed him by calling him a Communist and liar, and moreover that NBC had tapped his private telephones. The case was to drag on inconclusively for several years. In July, the newspapers learned from Representative Thomas that HUAC now intended to issue a subpoena requiring Chaplin to testify before his Committee. Chaplin did not wait for the subpoena: on 21 July the press reprinted the text of a dignified but sarcastic message which he had sent by telegram to Thomas:

From your publicity I note that I am to be quizzed by the House Un-American Activities Committee in Washington in September. I understand I am to be your single ‘guest’ at the expense of the taxpayers. Forgive me for this premature acceptance of your headlines newspaper invitation [sic].

You have been quoted as saying you wish to ask me if I am a Communist. You sojourned for ten days in Hollywood not long ago [while investigating Hanns Eisler], and could have asked me the question at that time, effecting something of an economy, or you could telephone me now – collect. In order that you may be completely up-to-date on my thinking I suggest you view carefully my latest production, Monsieur Verdoux. It is against war and the futile slaughter of our youth. I trust you will not find its humane message distasteful.

While you are preparing your engraved subpoena I will give you a hint on where I stand. I am not a Communist. I am a peacemonger.4

The fearlessness and fierce humour of this message give credibility to Chaplin’s description of how he imagined he would behave if he were eventually called before the Committee:

I’d have turned up in my tramp outfit – baggy pants, bowler hat and cane – and when I was questioned I’d have used all sorts of comic business to make a laughing stock of the inquisitors.

I almost wish I could have testified. If I had, the whole Un-American Activities thing would have been laughed out of existence in front of the millions of viewers who watched the interrogations on TV.5

The people who were closest to Chaplin doubted that he would ever have made such a public demonstration: if he had it would have been his greatest performance. He was subpoenaed, but three times the date was postponed until eventually he received a ‘surprisingly courteous’ reply to his telegram, saying that his appearance would not be necessary and that he could consider the matter closed. Perhaps they realized that such a comedian might steal the show.

In November, Chaplin was again defying America’s Cold War repressions. Deportation proceedings had now been instigated against Hanns Eisler. Chaplin cabled Pablo Picasso, asking him to head a committee of French artists to protest to the United States Embassy in Paris about ‘the outrageous deportation proceedings against Hanns Eisler here, and simultaneously send me copy of protest for use here’. ‘I doubt,’ reflected his son Charles,

if the incongruity of asking a confirmed Communist to intercede for a man accused of Communism in a non-Communist country ever even entered my father’s head. He was an artist appealing to another artist to come to the aid of a third artist. But to many people his move smacked of insolence, and the newspapers roundly castigated him for his lack of etiquette rather than for any subversion. How can you call such an open move subversion!6

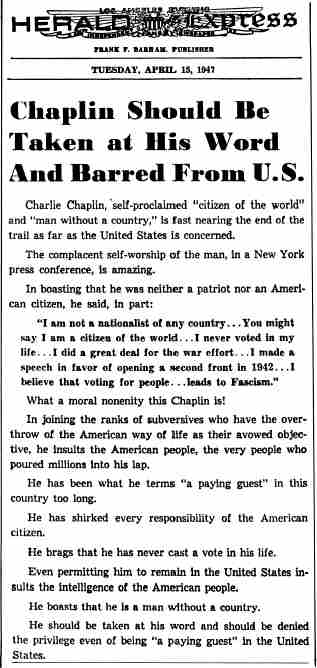

1947 – Leading article from the Los Angeles Herald-Express, illustrating the violence of McCarthyist attacks on Chaplin.

The New York chapter of the Catholic War Veterans did so, however, and sent a telegram to the Attorney-General and the Secretary of State demanding ‘an investigation of the activities of Charles Chaplin’. The activities in question were the cable to Picasso ‘noted French [sic] artist and (self-admitted) Communist’ and an ‘alleged attempt to interfere with the activities of a duly elected representative of our citizens’. The incident instantly stirred the FBI to initiate a new investigation ‘to determine whether or not Chaplin was or is engaged in Soviet espionage’. Almost two years later, when the Senate Judiciary Committee was seeking legislation to expel subversive citizens from the United States, Senator Harry P. Cain revived the Picasso incident as a reason to deport Chaplin: ‘It skirts perilously close to treason,’ he declared.

In an atmosphere of growing fear, Chaplin bore up bravely and refused to be intimidated or silenced. Even so it was not surprising that for his next film subject he turned back nostalgically to the London of his youth. He even considered making the film in London, and partly with this in mind decided to go to England, taking the opportunity to show Oona for the first time the scenes of his boyhood. Their plan was to return to California via the Far East.

In February 1948, he applied for the re-entry permit which, as an alien, he would need in order to return to the United States. The Immigration Department stalled on the application for some weeks and then, when reservations were already made on the Queen Elizabeth and at the Savoy, telephoned and asked him to report to the Federal Building. He told them he was busy that day and asked to come the following day, which was Saturday. They replied that they would save him the trouble and call on him. When the deputation arrived on 17 April 1948, it consisted of a stenographer, an FBI agent and an immigration officer, who told him that he had the right to demand Chaplin’s evidence under oath. The unexpected inquisition lasted for four hours and was all recorded by the stenographer. It began with personal questions about Chaplin’s racial origins – he said unequivocally on this occasion that he was not a Jew – and sex life. Describing the interrogation in a letter to Sydney, he said that when asked if he had ever committed adultery he countered, ‘What is a healthy man who has lived in this country for over thirty-five years supposed to reply?’ He found the enquiries into his life, thought and opinions ‘most personal, insulting and disgusting’. Asked about his political views, he refused as usual to shuffle. He told them frankly ‘that I was decidedly liberal; that I was for Wallace, and that I have no hate for the Communists, and that I believe that they, the Communists, saved our way of life. They were combating 280 divisions of the Germans at a time when we, the Allies, were unprepared.’7

The interrogation led him to try to sum up the political position in which a combination of instinct and rationalization had placed him:

Frankly I don’t know anything about the Communist way of life. I must say that, but I must say this, I don’t see why we can’t have peace with Russia. Their way of life – I am not interested in their ideology, I assure you. I assure you. I don’t know whether you believe me or not, but I am not. I am interested to the point where – they say they want peace, and I don’t see why we can’t have peace here. I don’t see why we can’t have trade relationship and ameliorate matters and so forth and avoid a world war …

I am progressive and I am progressive in the sense that I am not a Socialist, but I believe in proper people’s unionism and I believe it is a good thing. I believe in all that sort of thing that will alleviate … raise the standard of living of the American people and that is all; I’d like to avoid another depression …

I have no affiliations other than those that are outside of the political organization, like the friendship of Russia thing, you see. My only object is to preserve democracy as we have it. I think there are certain abuses to it, like everything else. I think there has been a great deal of witch burning. I don’t think that is democratic. I know it seems very strange and rather bewilders me why I should be considered a Communist. I have been here thirty-five years and my primary interest is in my work and it has never been anti-anything … maybe a critical comment, but it has always been for the good of the country. I don’t like revolution. I don’t like anything overthrown. If the status quo of anything is all right, let it go. In the sense of my being a liberal, I just want to see things function in harmony. I want to see everybody pretty well happy, and satisfied.8

Chaplin was told that the re-entry permit would be granted but that he would be required to sign a transcript of the interrogation. Pat Millikan, Chaplin’s lawyer, was impressed by the undoubted skill with which Chaplin had conducted the affair, but advised him not to sign until he was sure he actually intended to sail for England. In the end Chaplin decided against the trip. As soon as wind of his intention to leave the country reached the Treasury, they put in a claim for $1 million tax and demanded a bond of $1.5 million if he left the country.

As a result of Chaplin’s dexterity in handling the inquisition, the FBI’s Los Angeles office reported that further interviews with Chaplin were ‘not recommended … the interview for the most part was inconclusive because CHAPLIN would either deny allegations, explain them in his own manner or state that he did not remember’.9 Nevertheless, in November 1948, Chaplin was placed on the Security Index. The newspaper archives were combed anew. Absurd new evidence was gathered, such as that in 1929 Chaplin had been a member of something called ‘The Russian Eagle Supper Club’. News items about his failure to appear in the 1931 Royal Variety Show, and his thoughts on patriotism delivered on that occasion, were brought up against him. There was even an attempt to introduce Hetty Kelly into the case. A disgruntled former employee sent the Bureau off on a wild goose chase involving a fictitious courier who had brought a secret message to Chaplin from an agent in Moscow. A tip-off that there would be a clandestine meeting at Summit Drive launched a surveillance operation on the house, but of course no one arrived.

Despite these setbacks, in November 1949 the FBI had a request from the Assistant Attorney-General, Alexander Campbell, for the Chaplin files, since a ‘Security-R investigation was pending’. The files were disappointing: on 29 December there came the admission, ‘It has been determined that there are no witnesses available who could offer testimony that Chaplin has been a member of the Communist Party in the past, is now a member, or has contributed funds to the Communist Party.’10 There was a ray of hope for the FBI in 1950 when Louis F. Budenz, a former managing editor of the Daily Worker and a marathon namer of names, included Chaplin in his list of 400 ‘concealed Communists’ and alleged substantial contributions to Party funds. He turned out to be a singularly unreliable witness. Hoover ordered the Los Angeles office to reopen its investigation of Chaplin, without evident results.

To add to his private problems, Chaplin now found himself ‘a half-owner in a United Artists that was $1 million in debt’. His co-owner was Mary Pickford. It was a depressed period for Hollywood at large, and most of the other stockholders had sold back their shares. The repayments had depleted the company’s reserves, and Monsieur Verdoux, which it had been hoped would bring United Artists back into profit, instead threatened losses. Chaplin and Pickford found themselves in conflict. Pickford insisted on firing Arthur Kelly, who had resumed his role as Chaplin’s representative in the company. In turn, Chaplin insisted that Pickford should also dispense with her representative. They then failed to agree on an arrangement under which one of them might buy out the other’s interest. Various outside offers in turn faded away, and when an Eastern theatre circuit offered $12 million for United Artists, Pickford and Chaplin again failed to agree upon their respective participation in the arrangement. (The circuit’s offer consisted of $7 million in cash and $5 million in stock. Chaplin proposed that he should take $5 million cash down and leave the remainder for Pickford. On reflection, Pickford decided that, even though she made $2 million more, the advantage was Chaplin’s since she would have to wait two years for the balance of her money.) When they eventually sold out some years later it was for considerably less.

In post-war Hollywood, studio space was too valuable for Chaplin to leave the studio idle between pictures. During the years that he was preparing Limelight, the studio was regularly rented out to small independent production units like Cathedral Films, who made dozens of religious shorts there, such as The Conversion of Saul or The Return to Jerusalem. One of these rentals was in its way historic. On 5 and 25 May 1949, Walter Wanger rented the sound stage to make some screen tests of Greta Garbo, who had not appeared in a film for seven years, since Two-Faced Woman (1942). It was the star’s last appearance before the cameras. Historic too – or at least ominous in terms of the future effect of television upon the film industry – were the rentals of studio space to Procter and Gamble for the production of some of the earliest television commercials.

The secret of Chaplin’s fortitude in weathering the storms of the late 1940s was undoubtedly the unqualified success and happiness of his marriage. On 7 March 1946, when their first child Geraldine was nineteen months old, Oona gave birth to a son, Michael. During the time that Chaplin was writing Limelight the Chaplins had two more daughters, Josephine Hannah, born on 28 March 1949, and Victoria, born 19 May 1951. Geraldine’s Hollywood birthday parties were family events. On her fourth birthday, Rollie Totheroh came to the house and shot 1000 feet of film of the occasion; unfortunately it seems not to have been preserved. Among other relaxations there were summer weekends on a new yacht. From time to time, friends would be taken down to the studio to see Monsieur Verdoux and some of Chaplin’s older films. The new generation of Chaplin children were introduced to the films, too; on 5 December 1950, Oona took Geraldine, Michael and Josephine to the studio to see The Gold Rush for the first time. Between the births of Josephine and Victoria, Chaplin and Oona made four trips to New York. Their only brief period of separation was on the last of these, in January 1951, when Chaplin made the journey as usual by train while Oona flew.

Limelight was to be about the theatre. A contributory reason for the choice of this theme might have been Chaplin’s encounters with the live stage in the late 1940s, thanks to Jerome (Jerry) Epstein and the Circle Theatre. Epstein was a friend of Chaplin’s younger son Sydney, with whom he established the theatre in 1946. Although the Circle began in a modest way, giving performances in the homes of any friends with large enough drawing rooms, its very first production, The Adding Machine, with Sydney Chaplin in the leading role, attracted favourable notices. Sydney had already introduced Epstein to his father and Oona when they all met at a showing of Les Enfants du Paradis, and the Chaplins came to see Sydney’s performance. ‘Charlie was a wonderful audience,’ Epstein recalled,

and he just got to like the theatre. He would come all the time. When he’d nothing else to do, he would drive down in his little Ford, and sit with me in the box office. And then of course all his friends began to come to the theatre and they brought friends. Fanny Brice came; and Constance Collier took us up in a big way, and brought Katharine Hepburn and George Cukor, and Gladys Cooper and Robert Morley and any English people who happened to be in Hollywood. When we did Ethan Frome we borrowed props from the studio. Charlie was so impressed by our production of The Time of Your Life that he contacted Saroyan and asked him to give us a play, which he did: it was Sam Ego’s House.

Then one day he was watching a rehearsal of The Skin Game, and asked ‘Do you mind if I suggest something …?’ and of course in no time he had taken over the whole show. He was marvellous. His instinct was amazing – his feeling for the play, stage pictures, timing, exits, entrances, everything. Of course he acted out every part himself, and some of the actors as a result became little Charlie Chaplins. It was an unforgettable experience for them, though at this stage of the production it was very confusing for them too, altering everything they had already done.

After that he did five other productions. Of course he had not the patience to do them from the beginning, but he would come in at the end and give his touches. The next one was Hindle Wakes. Then he wanted to do Rain, which he said had never been done correctly. He considered that Jeanne Eagels’ performance had been overrated and that the Reverend Davidson was always done wrong. Sadie was June Havoc – that was the first time we had a real star, but she had come to the theatre and wanted to do the part. I had called Albert Camus in North Africa to ask if we could produce Caligula, and Charlie did it. It was a disaster: no one understood the play, least of all the actors. Although Charlie’s participation was never made public, or printed in the programme, he took it very personally when the play had bad notices, and I had to dissuade him from firing off letters to the press …

Charlie devised some wonderful gags for School for Scandal and even added a line. Marie Wilson played Lady Teazle, and the eighteenth-century dresses dramatically showed off her magnificent breasts. I had devised a card game, in which Wheeler Dryden stood behind Marie. Charlie suggested that when Wheeler peered over her shoulder, and Marie held the cards to her, Wheeler should simply say, ‘Madam, I was not looking at your cards.’ It really brought the house down.

Constance Collier would sit in on the rehearsals and there would be some very funny sparring between them. Constance would criticize, and he would become very mad. ‘But Charlie – you haven’t read the play,’ she would say; and he would snap back, ‘I don’t need to. I know what it’s about.’11

In her book Moments With Chaplin (1984), New York journalist Lillian Ross describes Chaplin putting his actors through a gruelling five-hour rehearsal (he thought nothing of working through until 6 a. m.). She reports verbatim some of his direction:

‘You must not act. You … must give the audience the impression that you’ve just read the script. It’s phoney now. We don’t talk that way. Just state it. Don’t make it weary. You’re too young for that. Let’s get away from acting. We don’t want acting. We want reality. Give the audience the feeling that they’re looking through the keyhole. This will be maudlin and sticky as hell if you act …’ Later he told them, ‘Keep it simple. Too many gestures are creeping in. I don’t like that. If the audience notices a gesture you’re gone. Gestures are not to be seen. And I’m a gesture man. It’s hard for me to keep them down … Thank God, I can see myself on the screen the next day … I’m essentially an entrance and exit man … Good exits and entrances. That’s all theatre is. And punctuation. That’s all it is.’

Chaplin told Epstein ‘When I make my film you’re going to work with me.’ To Epstein’s surprise he was as good as his word, and took him on as assistant on Limelight. Epstein was to remain an important collaborator and a close family friend for the rest of Chaplin’s life.

Chaplin was to spend almost four years on the script of Limelight – the longest period of time for any scenario he had written. The title Footlights is first mentioned in the studio records in the second week of September 1948, but Chaplin had already been dictating story ideas since the start of that year. Arthur Kelly in New York was asked to register the titles Limelight and The Limelight on 6 September 1950, and the ‘dramatic composition’ was sent for copyright five days later. As late as January 1951 Chaplin was still regularly dictating new script material to his then secretary Lee Cobin. The script as completed was filmed virtually without alteration, though one or two scenes were cut out before the film was released.

Chaplin’s approach to Limelight was altogether exceptional. He first set it down in the form of a novel, running to something like 100,000 words. This incorporated two lengthy ‘flashback’ digressions in which he related the biographies of his two main characters, the clown Calvero and the young dancer Terry Ambrose, before the beginning of the eventual film story. Much later, Chaplin was to say that the idea for Limelight was suggested by his memory of the famous American comedian Frank Tinney, whom he had seen on stage when he first came to New York, at the height of Tinney’s popularity. Some years later he saw him again and recognized with shock that ‘the comic Muse had left him’. This gave him the idea for a film which would examine the phenomenon of a man who had lost his spirit and assurance. ‘In Limelight the case was age; Calvero grew old and introspective and acquired a feeling of dignity, and this divorced him from all intimacy with the audience.’ Chaplin, in his sixties, must inevitably have taken a subjective view of this peril. Moreover, he was in the process of witnessing – painfully – how fickle a mass public could be.

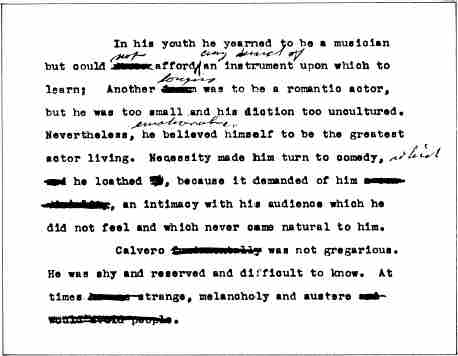

c.1949 – Passage from the first page of Calvero’s story in the ‘novel’ version of Limelight, with Chaplin’s manuscript revisions.

The full ‘novel’ form of Limelight indicates that this was a much more complex series of autobiographical reflections. At one level the young Calvero is the young Chaplin:

In his youth he yearned to be a musician but could not afford any kind of instrument upon which to learn. Another longing was to be a romantic actor, but he was too small and his diction too uncultured. Nevertheless, emotionally, he believed himself to be the greatest actor living.12

At another level, though, Calvero, the stage artist who loses heart and nerve and becomes a victim of drink, is Chaplin’s own father. Brought up by his mother, Chaplin had in his innocence always thought of her as the injured party, abandoned by her ne’er-do-well husband. Much later – and particularly after his own life provided domestic stability – he began to reconsider his feelings about his father. After all, Hannah had been unfaithful and promiscuous, as the affair with Leo Dryden suggested. The description of Calvero’s marriage to Eva Morton, her infidelity and the consequent despair which drives him to alcoholism, is no doubt Chaplin’s own attempt to explore his parents’ problematic relationship.

Terry is also given a biography. It is clear that these flashback stories were never intended to figure in any eventual scenario but were Stanislavskian studies to provide background for the characters. Terry’s mother resembles the adult Hannah Chaplin. She is seen as a woman worn by suffering but still beautiful, bent over a sewing machine, slaving to make a meagre living for herself and her two children. These two children parallel the close sibling relationships that figured so large in the Chaplin history: Charles Senior and his protective brother Uncle Spencer, Hannah and Kate, Chaplin and Sydney, young Charles and young Sydney. Especially since Aunt Kate remains such a mysterious and fascinating figure in Chaplin’s childhood, it is intriguing to speculate how much of her and Hannah there is in Chaplin’s picture of the relationship of Terry and her elder sister Louise. It seems appropriate, for the intimations they give of Chaplin’s own reflections on his family history, to record the content of the Limelight ‘novel’ at some length in the following pages. The ‘novel’ is in itself notable for the Dickensian relish of Chaplin’s descriptions of Victorian life and the theatre of his boyhood.

The story begins much like the film, with Terry’s attempted suicide in Mrs Alsop’s lodging house – ‘supine, a little over the edge of the iron bed’. Outside a barrel organ plays ‘Why did I leave my little back room in Bloomsbury?’ In flashback we are told the story of Terry’s youth.

The daughter of the fourth son of an English lord and a servant girl, Terry lives with her widowed mother and her older sister Louise in a poor room off Shaftesbury Avenue. Louise loses her job in a stationery shop, and the mother is taken off to hospital. Life improves somewhat when Louise starts to bring home a little money. Terry discovers with shock how she earns it, when she wanders with some other children into Piccadilly and sees Louise at work as a street walker.

Before Terry is ten, her mother dies and Louise becomes the mistress of a South American with ‘a small, luxurious flat in Bayswater’. She sends Terry to boarding school and pays for her dancing lessons. When Terry is seventeen Louise emigrates to South Africa. Terry becomes a dancer at the Alhambra. On the threshold of success, however, she is struck dawn with rheumatic fever. When she leaves hospital she goes to work at the stationer’s and toy shop where Louise was formerly employed, Sardou and Company:

a small establishment, overstocked with newspapers, magazines, stationery requisites, indoor games and other miscellany. The shop was close, oppressive, and had a pungent odour of ink, leather goods and the paint of toys … Sardou and Company was Mr Sardou, there being no company.

It is at Sardou’s that she encounters a young composer, Ernest Neville. She loses her job when, out of pity for his evident poverty, she deliberately makes a mistake with his change.

Autumn was near, and London was preparing for her coming theatrical season. Dancing troupes, acrobats, trick cyclists, conjurors, jugglers and clowns were renting Soho’s clubrooms and vacant warehouses for rehearsals. Theatrical props, costumes and wigmakers were feeling the season’s rush. A recumbent giant that would cover the whole stage and that breathed mechanically, was being built in parts for the Drury Lane pantomime, so large that a ballet could enter out of its breast coat pocket.

Special devices for Cinderella’s transformation scene; pumpkins to be transformed into white horses, contrived by aid of mirrors; paraphernalia for flying ballets, cycloramic tricks, horizontal bars and tight-ropes. Orders for new conjuring tricks, odd musical instruments, padded wigs and slapstick contraptions of all kinds, all to be ready for Christmas.

Terry, six months after her collapse and desperate for work, takes a job at Northrups’ Pickle Factory. Her hands become stained yellow with the pickle and at weekends she wears black gloves to hide them. One Saturday night she walks into a room over a Soho pub where a ‘Mr John’ is rehearsing some dancers. He is ‘a brutish-looking man with a broken nose, a large ugly mouth and a voice low and woolly that sounded like the drawing of a bow over a loose, bass string of a violin’. Terry asks ‘Mr John’ for a job. He auditions her, but after dancing she collapses. The dancers are frightened when they see her yellow hands, and take her to hospital where she remains eighteen weeks. Meanwhile ‘Mr John’ and his wife befriend her, and before leaving with his troupe for an American tour he gives her a sovereign. Leaving hospital she moves into a room at Mrs Alsop’s for five shillings a week. (Mrs Alsop wisely requires two weeks in advance; after six weeks Terry is four weeks’ rent in arrears.)

While scanning the job advertisements, Terry notices that Sir Thomas Beecham will conduct a new symphony by Mr Ernest Neville. She uses one-and-sixpence of her precious remaining four shillings to buy a gallery ticket. Afterwards she sees Neville leaving the Albert Hall with Sir Thomas Beecham. She speaks to him and reminds him that she was the girl in Sardou’s, but he does not pursue the conversation. It is at this point that she returns to her room and attempts to commit suicide.

From this point the ‘novel’ coincides with the scenario of the finished film. Calvero returns to find the girl in a gas-filled room, sends for a doctor, and takes her under his wing. As she begins to recover, he tells her his own life story – the Calvero ‘novel’.

Many years ago Calvero suffered unrequited love for a young woman who ran away with his rival to South Africa, where she married. In course of time her grown-up daughter, having run off with a young doctor, arrives in England. Abandoned by the young man, the girl, Eva Morton, appeals for help to Calvero, about whom she has heard from her mother. In a short time they become lovers, following a blissful summer’s day on the Thames.

It was a day of flamboyant color; of white flannels and gay parasols; of baskets of strawberries, bright yellow pears and large blue grapes; it was a day of lemon and pink ices, and cool drinks in long-necked bottles; a day of occasional guitars and the rippling of punts and rowboats, gliding through the water.

And so it was that Calvero and Eva spent the week-end at Hanby. On their way back, they stopped for dinner at a small inn at Staines, and spent the night there. Soon after, Calvero gave up his rooms in Belgravia and moved to a flat off Oxford Street, where he and Eva lived as man and wife, and within three months they were married.

Very soon, however, Calvero realizes that Eva is being unfaithful to him:

She … understood her own love for him which had a special place in her heart, but which did not wholly occupy it: no man ever could. She realized that her desire was insatiable and verged on being pathological, yet she looked upon it as something separate and apart from herself and her life with Calvero.

Of her unfaithfulness she wanted to tell him. She hated deception because she had a deep regard for him. She wanted to make a clean breast of everything and tell him that she could never be faithful to any man, but she felt that Calvero would not tolerate any compromise. And she was right. His nature demanded the full possession of the thing it loved. His reason might conceive a true justification for her promiscuity, yet to acquiesce to it, he knew that such a love would slowly die from its own poison.

This reference to the nature that ‘demanded the full possession of the thing it loved’ has clearly relevance to Chaplin’s own experiences with May Reeves and Paulette Goddard; here also he seems to be exploring the break-up of his parents’ marriage.

Matters come to a head when Eva has an affair with a rich Manchester factory owner called Eric Addington. Calvero discovers the affair while playing principal clown in the Drury Lane pantomime, with Addington and Eva watching him from a box. Having introduced into his stage business some wry comedy about the heart-broken cuckold, he afterwards accuses the couple. Eva leaves him for ever.

Calvero begins to drink. The more he drinks the less appeal he has to his audience. He is advised by his dresser, who was once a famous clown himself,

‘The more you think, the less funny you become. The trouble with me,’ he continued, ‘… I never thought, it was women that killed my comedy. But you – you think too much.’

And the dresser was right. Calvero was instinctively analytical and introspective. He had to know and understand people, to know their fallibilities and weaknesses. It was the means by which he achieved his particular type of comedy. The more he knew about people, the more he knew himself; an estimation that was not very flattering; with the consequence that he became self-conscious and had to be half-drunk before going on stage.

Calvero’s mind fails under the strain. He wanders for six weeks in a state of amnesia, and is then confined for three years in an institution. On his release he is aged and changed. He attempts to make a comeback in the theatre, but succumbs once more to drink. The audience walks out on him. ‘His engagements grew less, as well as the salary he was asking, until his vaudeville engagements ceased entirely.’ Calvero sinks to work as an extra, though he remains a celebrity in The Queen’s Head where he mingles with people he knew in his better days – vaudevillians, agents, critics, jockeys, tipsters. A particular friend is Claudius, the armless wonder. Claudius recognizes Calvero’s impecunious state and offers him a loan. Calvero is obliged to take the money from Claudius’s wallet himself, and in doing so sees a photograph of a youth. Claudius explains that it is his nephew whom he has educated since the death of his sister, the boy’s mother. Calvero has to button up Claudius’s coat for him before he goes out into the cold. (Calvero is later able to repay Claudius’s loan, since he stakes half of it on a 3–1 winner.) ‘It was after one of these dialectic – not to say alcoholic – afternoons that he came home and found Terry Ambrose, unconscious in her back room.’

From this point the ‘novel’ version of Calvero’s story also follows the essential line of the film script, apart from some inconsiderable differences of detail and plot mechanism. The result of the friendship and mutual encouragement between Calvero and Terry is that she is cured of the psychosomatic fear that she will never be able to dance again, while he is heartened to attempt a comeback. While Terry’s career prospers until she becomes principal dancer at the Empire, however, Calvero’s once more fades. Terry convinces herself that she is in love with this benefactor, old enough to be her father; but when she once more meets Neville, the young composer (she is to dance in his ballet), Calvero understands her heart better than she does herself, and discreetly disappears from her life.

Calvero is rediscovered, and the manager of the Empire, Mr Postant,13 organizes a benefit performance for him, at which he will be the star. In the ‘novel’ version of the story, Chaplin has not yet worked out the mechanics of the end. In the film, the performance takes place, and Calvero has one more triumph with the public. When he takes his bow, carried in the drum into which he has fallen as the climax of the act, the audience applauds wildly, unaware that he has suffered a heart attack. He dies as his protégée dances on the stage, in illustration of the archaic, 1920s-style title that prefaces the film:

The glamor of Limelight, from which age must fade as youth enters.

A number of passages exclusive to the ‘novel’ version of Limelight are interesting for their autobiographical and factual references. At one moment, Calvero tells Terry that he is going to see a new flat in Glenshaw Mansions – where, of course, the Chaplin brothers had their first bachelor apartment. The illness which is to prove fatal to Calvero is a circumstantial recollection of the elder Chaplin’s last days, and the last time his son saw him alive, in the saloon of The Three Stags in Kennington Road:

The doctors had warned him only a few months ago that further dissipation would be extremely dangerous to his health. It was eleven o’clock in the saloon bar of the White Horse, Brixton, that Calvero, in the midst of his febrile hilarity, collapsed into unconsciousness and was taken to St Thomas’s Hospital.

(Charles Chaplin Senior died in St Thomas’s.)

Calvero’s exhortation to Terry could be the credo of Chaplin’s whole working life:

She must always adhere to the living truth within herself. She must be deeply selfish. That was essential to her art, for her art was her true happiness.

An intriguing scene which was eliminated from the final film script introduced a historical figure, the great juggler Paul Cinquevalli (1859–1918). Attempting a comeback at the Alhambra, Calvero meets Cinquevalli at the morning rehearsal. The juggler tells him that he intends that evening to perform a new trick with billiard balls that he has been rehearsing for seven years. That night they share a dressing room. Cinquevalli returns from the stage and Calvero asks him how the new trick went. Cinquevalli says that it received no applause: he had made it look too easy. Calvero says that he should have fumbled it a couple of times. Cinquevalli replies that he is not yet good enough to do that.

‘I shall need a little more practice.’

‘I see,’ said Calvero ironically. ‘And now I suppose it’ll take another ten years to learn how to miss it.’

Cinquevalli smiled. ‘That’s right,’ he replied.

‘That’s depressing,’ said Calvero.

‘Why?’ he asked.

‘I can’t laugh at that. It’s frightening. Perfection must be imperfect before we can appreciate it. The world can only recognize things by the hard way.’

‘That should be encouraging. The world can only recognize virtue by our mistakes.’

‘If that were the truth,’ said Calvero, ‘I’d be a saint by now.’

To judge from his working notes, Chaplin seems to have considered retaining this scene in the film, placing it immediately before Calvero’s final appearance on the stage, and setting it in the wings. Finally, though, it was discarded altogether.

Chaplin was fascinated by the problems of creating a ballet, ‘The Death of Columbine’, for the film. In the past he had always composed his music after the film was finished. In this case the music had to come first. He began to work on the twenty-five-minute ballet sequence (it was to be much shorter in the finished film) with the arranger Ray Rasch in December 1950. They were to work together on the ballet for several days a week until the following October. A special problem was to compose a forty-five-second solo to which André Eglevsky, the dancer Chaplin wanted for the role, could match his choreography for the Blue Bird Pas de Deux. In September, the music was recorded with a fifty-piece orchestra under Keith R. Williams. Eglevsky and his partner Melissa Hayden flew in for two days from New York to hear the music and to rehearse some of the dancing. Chaplin was extremely nervous as to their verdict, but they were apparently quite satisfied that his music was appropriate for ballet.

Chaplin told his sons that he expected Limelight to be his greatest picture and his last. As contented in his family life as he was disillusioned with post-war America, he spoke from time to time of retiring. Had he done so, Limelightgoing right back to his beginnings, would have been a perfect ending to his career. It was, in any event, to round off the Hollywood period.

The film was something of a family affair. As the juvenile lead, the young composer Neville, he cast his tall, handsome younger son by Lita Grey, Sydney Chaplin. Sydney remembered that his father asked him to play the part in June 1948, three years before he was to begin the film. Much later he discovered that his role was that of a starving musician, ‘and as at this time I weighed over eighteen stone, had access to plenty of food, and what is called a crew haircut, father suggested that I should go on a diet and grow my hair’.14

Charles Junior had a small role as a clown in the ballet. Geraldine, Michael and Josephine were to appear in the opening of the film, as three urchins who watch with curiosity Calvero’s drunken return to his home. Geraldine even had a line to speak – her first in the movies. In the part of the doctor who looks after Terry after her suicide attempt, Chaplin cast Wheeler Dryden, a lean, somewhat wizened figure, wearing spectacles and with an emphatically British accent. Although Wheeler had been around the studio since The Great Dictatorthis was the first time that his relationship with the Chaplin brothers had been made public by the studio:

Our mother and my father separated and Charlie and I never met again until I came to America in 1918 [sic]. Charles was already famous.

We both agreed that it would be better for me to make good on my own. This is the first time our relationship has been disclosed.

We have both remained British subjects. Not that we are un-American, but although we are fond of America, we do not feel it necessary to give up our British heritage.15

Chaplin’s major problem was to find a leading lady. She had to have, said Chaplin, ‘beauty, talent and a great emotional range’. She also had to be very young and preferably English.

An advertisement was placed in the papers reading ‘Wanted: young girl to play leading lady to a comedian generally recognized as the world’s greatest’, and for another year Father saw and tested just about every applicant who seemed even vaguely suitable for the part. It was the first time that Father had written a film in which the girl’s part was equal to his, and so it was terribly important that he made the right decision.16

Sydney somewhat exaggerates the length of the search: the first girls were interviewed in February 1951 and the choice was made by August. Sydney himself was given the job of screening applicants, with the help of Chaplin’s secretary at the time, Lee Cobin. The playwright Arthur Laurents, who was currently friendly with the Chaplins, recommended twenty-year-old Claire Bloom, whom he had seen in London in Ring Round the Moon (Christopher Fry’s adaptation of Anouilh’s L’Invitation au château) at the Globe Theatre. Laurents himself telephoned Miss Bloom to ask her to send some photographs of herself to the Chaplin studio. The idea seemed so fanciful and remote to the young actress that she put the whole thing out of her mind until a few weeks later when she received a cable, ‘WHERE ARE THE PHOTOGRAPHS? CHARLES CHAPLIN.’ When the photographs arrived, Harry Crocker, who had now rejoined Chaplin to work on publicity, telephoned from California to say Chaplin wanted to test her for the part. Since the theatre management would only release her from Ring Round the Moon for one week, it was agreed that she should fly to New York and Chaplin would meet her there to make the test. Miss Bloom was chaperoned by her mother; Chaplin brought with him his assistant Jerry Epstein. From the moment he met the Blooms at the airport, Chaplin talked with great excitement of his plans:

He said the love story – so he described it – took place in the London of his childhood. The opening scenes were in the Kennington slums where he was born. The agents’ offices where he had endlessly waited for work, the dressing rooms in the dreary provincial theatres, the digs, the landladies – all his melancholy theatrical memories were to be the film’s backdrop. He reminisced about the Empire Theatre, the smart music hall of its day, frequented by the smartest courtesans; he talked of his early triumph as a boy actor in a stage adaptation of Sherlock Holmes … When we went to his rooms for lunch, he continued with his memories of London and seemed desperate to hear that nothing he had known had changed. In the last few years he had been deeply homesick, he said, but he didn’t dare to leave America for fear that the U.S. Government wouldn’t allow him to re-enter the country. His family, home, studios, money – everything was in America …

In the evening Chaplin would take us and Jerry Epstein to dinner at the most elegant restaurants. At the Pavilion and the ‘21’ Club he spoke endlessly of his early poverty; the atmosphere he was creating for Limelight brought him back night after night to the melancholy of those years at home with his mother and brother. He spoke either of the early poverty or of his troubles with the U.S. Government, troubles I wasn’t quite able to grasp until I had spent a while in Hollywood.17

Chaplin rehearsed Miss Bloom every day throughout the week. A little reluctantly, he permitted her to see the script, though she was not allowed to take it to her room, but had to return it to Epstein every night. Like other players of younger generations, she was surprised by Chaplin’s singular method of direction:

Chaplin was the most exacting director, not because he expected you to produce wonders of your own but because he expected you to follow unquestioningly his every instruction. I was surprised at how old-fashioned much of what he prescribed seemed – rather theatrical effects that I didn’t associate with the modern cinema.18

At the end of the week the screen tests were made at Fox Studios. Epstein was behind the camera while Chaplin worked in front of the camera with Miss Bloom:

I was trying out for the role, Jerry hoped he would please Chaplin as assistant director, and Chaplin was watching the script he had worked on for three years finally come before the camera, so everyone was tense.19

She was later to discover that Chaplin’s methods in directing the tests were the same that he would use in front of the cameras:

I was close to panic … only until I saw that Chaplin intended to give me every inflection and every gesture exactly as he had during rehearsal. This didn’t accord with my high creative aspirations, but in the circumstances it was just fine. I couldn’t have been happier – nor did I have any choice. Gradually, imitating Chaplin, I gained my confidence, and by the time we came to the actual filming I was enjoying myself rather like some little monkey in the zoo being put through the paces by a clever, playful drillmaster.20

Claire Bloom recalled Chaplin’s care in choosing the costumes for the tests, and how he would talk of the way his mother had worn such a dress or how Hetty Kelly had worn a shawl: ‘I quickly realized, even then, that some composite young woman, lost to him in the past, was what he wanted me to bring to life.’ She also remembered with amusement the embarrassment of Chaplin and Epstein when they realized that no one had seen her legs, which, since she played a dancer, were going to be important. Somewhat transparently they included a tutu and tights among the costumes she tried, even though no dance sequence was to be included in the tests.

The young actress returned to London with the promise that she would have some news after ten days, and the encouragement that Chaplin had presented her to someone in a restaurant as ‘a marvellous young actress’. In fact, four months passed with no news apart from a wire from Harry Crocker saying that she would hear further in a fortnight (which she did not). Despondency – especially after the Daily Express printed an article saying that Chaplin did not like the test that had cost him so much to make – gave way to resignation.

Chaplin was much occupied during this period. He arrived back from New York on the Santa Fe Chief on 1 May, and ran the Bloom tests the same evening. Oona was nearing the end of her pregnancy, and on 19 May gave birth to Victoria. Two days later, while mother and baby were still in St John’s Hospital, Chaplin moved out of 1085 Summit Drive to temporary accommodation at 711 North Beverly Drive, while the builders moved in to the old home. The growing family and their nurses demanded more room. The pipe organ was usurped. The majestic hall was divided with a new floor to provide more bedrooms. The alterations cost some $50,000 and seemed to demonstrate the Chaplins’ firm intention of staying. ‘My father,’ remembered Charles Junior, ‘was so proud of these rooms he liked to take his guests upstairs to show them off.’21

He was in fact still not convinced that Claire Bloom was the right choice. Again and again he would run her tests. Often he would invite guests to see some film at the studio, and then slip in the tests as well in order to get their views. Meanwhile he continued to interview other actresses and look at films in which there were likely young candidates. The strongest contender was an actress called Joan Winslow, who was brought from New York to Hollywood to go through the same process of extensive rehearsal and screen testing as Miss Bloom had undergone in New York. She stayed ten days, and was even shown the Bloom tests. Finally, however, Chaplin made up his mind and Miss Bloom’s agent received the fateful call from Harry Crocker. The contract gave her three months’ work at $15,000 plus travel expenses and a weekly allowance for herself and her mother.

The Blooms arrived in Hollywood on 29 September 1951, and at dinner at Summit Drive, with Oona and Epstein, Chaplin explained how Miss Bloom would spend the seven weeks till shooting began. Like Chaplin himself, she had to diet. She was to begin each day by going with Oona to exercise at the gymnasium, then rehearse from eleven until four and round off the day with an hour’s ballet class. Generally the rehearsals took place in the garden at Summit Drive. Miss Bloom was again struck by Chaplin’s insistence on his boyhood memories. When they went for a costume fitting he told her, ‘My mother used to wear a loose knitted cardigan, a blouse with a high neck and a little bow, and a worn velvet jacket.’ ‘Melancholy,’ she noted, ‘was a word he was to use frequently when speaking of his plans for Limelight.’22

The Blooms came to know the Chaplins at a time when their social life was much quieter than in the past. As Charles Chaplin Junior commented:

It must not be supposed that my father’s fight for his convictions was made without sacrifice. When I came back from the East to play my part in Limelight I was saddened to see the effect his stand had had on his own life. It was no longer considered a privilege to be a guest at the home of Charlie Chaplin. Many people were actually afraid to be seen there lest they, too, should become suspect.

Tim Durant, the irreconcilable Yankee, solid as a New England rock in his loyalty, was around, and he did his best to bring back some of the old life, noting the irony the while. Once his phone had rung steadily with people calling him, offering him favors, wining him, dining him in the hope that he would extend them an invitation to the Chaplin home. Now it was Tim’s turn to phone them and beg them to come up for a game of tennis. But they all backed out. The little tennis house and green lawn where once my father had held a gracious court were practically deserted on Sunday afternoons. I think my father must have been the loneliest man in Hollywood those days.23

There were still Saturday night dinner parties for one or two friends, however. At the Chaplin home, Claire Bloom met Clifford Odets, Carole Marcus – Oona’s girlhood friend, then married to William Saroyan and later to Walter Matthau – and James Agee, the shy film critic who had become a friend since his passionate defence of Monsieur Verdoux, and had now arrived in Hollywood as a screenwriter.

Not many of the old studio staff remained, and once again Karl Struss was to replace Roland Totheroh as cinematographer. As Claire Bloom remembers it,

the first three days’ filming had to be scrapped, because Chaplin was dissatisfied with the camera work of his old associate Rollie Totheroh. He then engaged Karl Struss, a more up-to-date technician, to replace Totheroh, and this cast a gloom over the set. Totheroh had shot most of Chaplin’s earlier films and, as he was no longer young, it was clear that this was probably the last job of his career … Chaplin, generous and loyal as he could be in pensioning his workers, was utterly ruthless when it came to the standards he’d set for his film.24

Totheroh was in fact credited as ‘photographic consultant’. Jerry Epstein remembers him taking special care over the filming of Chaplin himself. ‘He would watch everything and say “Head up … head up, now … We don’t want to see those double chins … gotta look pretty.”’25

The visual recreation of the London of Chaplin’s memories was all-important. After another designer had submitted some unsuccessful sketches, Chaplin had his production manager call Eugène Lourié. Lourié had emigrated from Russia in 1919 and had worked as a designer in France since silent days. In the 1930s he began an association with Jean Renoir, which continued after Renoir moved to Hollywood during the Second World War. It is likely that Chaplin had noted Lourié’s work in Renoir’s Diary of a Chambermaid (1946), in which Paulette Goddard had starred. Lourié remembered that Chaplin’s production manager had telephoned and asked him if he knew London and had ever worked there (he had, while designing a ballet for the De Basil company in 1933), and told him that the studio would pay minimum rates. Lourié was not told the identity of the producer until he reported to the studio. ‘I was pleased. I had a great admiration for Chaplin – but I was sorry I didn’t ask for more money.’26 Chaplin suggested that before making a definite commitment, Lourié should read the script and work for a fortnight on some sketches. This approach impressed Lourié: ‘In Hollywood they mostly hire film architects like stage hands.’

Chaplin was pleased with Lourié’s drawings.

He had talked to me exclusively about London. I had a nostalgic feeling for the place, although I had lived there only three months when I was designing the ballet for De Basil. Later, though, I visited Georges Périnal there, and he took me all over. He took me to the other bank of the river, where Chaplin had been brought up. I remember that at that time of night the streets were very dark. The only lighted windows were the undertakers’ shops. It was very curious to me, those lit windows with coffins inside. Anyway, he liked my ideas, and said, ‘Well, start’. Then he took me into his drawing room and played me the music he had composed for the film.27

The first set which Chaplin needed, so that he could start rehearsals with Claire Bloom, was the apartment at Mrs Alsop’s.

He was very anxious to have the view from the window – high brick houses and sad-looking urban back yards. Instead of using the usual painted backgrounds, I built it three-dimensional in miniature. I took a lot of time to dress it, with drying washing and lights in the windows for the night scenes. In the finished picture though I saw practically nothing of it. It looked to me just like a painted background!28

After the first day’s work in this apartment set, Chaplin took Lourié aside and told him he needed more distance between the door and the stove: ‘I rehearse it like a ballet. I need a particular distance to get in all the steps. Can we change it?’ Lourié, anticipating possible changes, had made the walls of the set three feet longer than was apparently necessary. He was thus able to make the change without difficulty, so that Chaplin could carry on with his rehearsals the following morning.

He was very impressed. I think from that day he had more confidence in me. At the beginning he was very cautious with me. The second thing which gave him confidence I think was when I showed him the three-dimensional model I made for the set for the pantomime. I made it in very forced perspective, with the ceiling sloping down to two feet from the stage. He liked it. After that he would say, ‘Mr Lourié, give me a composition for the frame.’

For the exteriors we could not go to London, of course. Travel was restricted then, and we were working on a shoestring budget. For the street I had to build it or find it. I actually found it. It was a New York brownstone street at the Paramount studio – a very old set, which very much resembled London. I showed it to Chaplin. He said ‘It’s wonderful.’ We slightly remodelled it. We changed the entrances to the houses, and built exteriors for two pubs and the physician’s office.

He had a very strong visual impression, though he could not always express it in words. He would draw things, though. I have two or three sketches that he made – I think of street lamps for the Victoria Embankment scene. We used back projection for the scene and one lamp and one bench – the bench may still be around his old studio somewhere.

Vincent Korda was extremely helpful. He sent me lots of research about the old Empire Theatre – old photographs. And he sent out the studio stills man at night to photograph the Embankment. I wanted a point opposite Scotland Yard, with Big Ben in the background. I asked him to photograph the scene every hour from dark until dawn, so that I could choose the light.

Basically the film was shot in the studio. We needed a theatre – several theatres in fact, since he wanted to do a montage of the dancer’s international tours. The choice was between using the Pasadena Playhouse or one of the two theatre sets at Universal (it had been built for Phantom of the Opera, and was still called ‘the Phantom stage’) and RKO-Pathé. We chose Pathé. It was a complete theatre, so that we could do the backstage stuff there too. And it’s much easier working in a studio than in a real theatre, because you can change things as you please.

I was very excited to find some old backdrops from The Kid in the studio. And then I found some old scene painters from the 1880s to make the backdrops for the stage scenes.29

Jerry Epstein and Wheeler Dryden were credited as assistant producers, although Eugène Lourié did not remember Wheeler as being very active on the film apart from his appearance as an actor. ‘He was around all the time though, because he was then living in a house at the studio.’ Robert Aldrich also worked on the film as associate director.

I think he was brought in because Chaplin felt he wanted someone with a lot of professional experience of studio work. But Aldrich always wanted more artistic shots. Chaplin did not think in ‘artistic’ images when he was shooting. He believed that action is the main thing. The camera is there to photograph the actors. I worked with Sacha Guitry, and he had exactly the same approach.30

Without any significant departure from the script, Chaplin worked with the same discipline as on Monsieur Verdoux. He fell two weeks behind the tight shooting schedule he had given himself, and Claire Bloom’s engagement lasted (to her delight) longer than the anticipated three months. Even so, the film was finished in fifty-five shooting days, including four days for retakes. This was a very far cry from the interminable shooting histories of The Kid or City Lights. Sydney Chaplin Junior recorded some impressions of his father at work:

We started with some bedroom scenes which lasted three weeks. Then came the street scenes, and it was while these were being shot that I noticed one of the extras was wearing a strange, mustard-coloured suit which looked to me quite terrible. I called Father’s attention to this, and he laughed and said it was strange but he’d had a suit just like it at one time. Of course, the one worn by the extra was rented from a firm of costumiers, but, without quite knowing why, the extra looked at the label in the inside pocket. It read: ‘Made for Mr Charlie Chaplin, 1918’.

Another time it was Father who objected to a jacket I was wearing. ‘Just look at the length of its sleeves compared with those of your shirt,’ he complained. ‘Get the tailor to lengthen them [the jacket sleeves] straightaway.’ I went away, rolled up my shirt sleeves a little, and came back. ‘Now that’s more like it,’ said Father.

He is, of course, a really wonderful director, using the right approach all the time, knowing instinctively how to treat each different artist. There was one old actor who was so nervous of playing with Father that he kept muffing his lines. To put him at his ease, Father muddled his own lines on purpose, and after that the old actor was at ease and the scene was exactly right the next time through.

And, of course, as well as being the film’s director, Father was also its principal actor. His difficulty was to imagine how he would look in a scene which he wouldn’t actually be able to see until it was filmed, and his method was to work out the moves in advance and have his stand-in go through them while he watched through the camera. One moment he’d be behind the camera, the next up 40 ft of scaffolding explaining something to an electrician, the next strolling around on the stage demonstrating some point to another actor …

It was hardly surprising that Father ran himself practically ragged. He was always the first to arrive at the studios in the morning and the last to leave at night. His wife Oona would come down about midday with some sandwiches and fruit pie for him. He’d go home at night exhausted and after dinner start right away planning the next day’s work.

I only remember one major crisis, that was over a very emotional scene between Father and Claire. He spent the whole day on this scene, which on the screen lasts a bare three minutes, and he still wasn’t satisfied – chiefly with his own performance. So he spent the next day re-shooting it, and the day after that. Finally there was a terrific take which had all the stage hands weeping and at the end wildly applauding. For the first time in three days Father allowed himself a smile.

The following day the people who were developing the film rang up to say that owing to some technical difficulty that piece of film had been destroyed. Father hit the ceiling when he heard this; but he didn’t have the heart to tell Claire. He just said that he still wasn’t satisfied and that he wanted to try it again.31

Claire Bloom found herself particularly apprehensive about the scene in which she suddenly finds that she can walk again, since she always had difficulty in weeping to order. Chaplin clearly had none of the inhibitions he experienced in directing Jackie Coogan’s crying scene. Before the scene began he criticized her acting so severely and became so angry that she burst into tears. The camera crew had been forewarned and snatched the scene in a single take. ‘Chaplin had judged perfectly what would do the job – rather like Calvero understanding what magic would be required to make Theresa walk again.’

In general, however, Chaplin remained patient and understanding with his actors. Eugène Lourié remembered him as being charming to his two sons. Charles Junior, though he evidently worshipped his father, had a different recollection:

And now, at last, it was Syd’s and my turn to be targets of that drive for perfection which ever since our childhood we had seen focused upon others. After that experience I was more than ever convinced that my father’s towering reputation and his seething intensity make it almost impossible for those working under him to assert their own personality. No one in the world could direct my father as he directs himself, but I feel that lesser actors in his pictures might profit from being directed by someone else.

With Syd and me he was, I believe, even more exacting than with the others. As his sons we could not appear to be favored, and so he went to the opposite extreme and even tended to make examples of us. He was especially tough on Syd as the young romantic lead, and sometimes I heard people commiserating with him. But I never heard Syd himself complain. He kept his equanimity and learned from my father and was rewarded by being praised in the reviews for his fine performance.32

Sydney and Claire Bloom became romantically attached during the filming. She remembered that away from the set Sydney would be

wickedly funny about his strong-minded father’s eccentricities, but once Sydney reported to begin his role in the film, he lacked all defensive wit and, confronted with those paternal ‘eccentricities’, became nervous and wooden on the set.33

Just before Christmas 1951 the unit moved to the RKO-Pathé studios for the theatre sequences. The backstage scenes were filmed first, and on the last day of the year, Chaplin began to shoot the performance scenes on stage. For the ballet scenes, Melissa Hayden was ingeniously doubled for Claire Bloom:

When the camera was close enough to permit me to do so [I was required] to wheel into frame and out as fast as possible – whereupon Melissa would take over again. The effect was so convincing that for years afterwards I was complimented on my dancing.34

A touching aspect of Limelight is the appearance of Buster Keaton in a double act with Chaplin – a crazy musical duet. This was the only time the two greatest comedians of silent pictures appeared together, and the only time since 1916 that Chaplin had worked with a comic partner. Buster Keaton, like Chaplin schooled in vaudeville, arrived in Hollywood in 1917. Some photographs from that period show Chaplin fooling with the young Keaton and Roscoe Arbuckle while visiting Arbuckle’s Balboa Studios.

In Limelight, Keaton played a crumbling and myopic pianist, who is assailed, the moment he takes his seat at the piano, by an avalanche of tumbling sheet music. Chaplin–Calvero, as the violinist, has his own problems: his legs for some inexplicable reason keep shrinking up inside his wide trousers. The unhappy consequences of Buster’s attempt to give his friend an ‘A’ escalate until the piano strings burst in all directions while Calvero’s violin is trodden underfoot. Eventually, after Calvero has produced a new violin, the performance begins. Calvero passes from a poignant melody, which reduces him to tears, to a demonic vivace which eventually precipitates him into the pit. He falls into the bass drum and is carried therein to the stage to take his bow.

Keaton worked on the film for three weeks, from 22 December to 12 January. On the Limelight set, he was reserved to the point of isolation. He arrived, Jerry Epstein recalled, with the little flat hat he had worn in his own films and had to be gently told that Chaplin already had a costume and business worked out for him. The whole unit was enchanted to see, however, that once on stage, Chaplin and Keaton became two old comedy pros, each determined to upstage the other. ‘Chaplin would grumble,’ Eugène Lourié remembered; ‘he would say, “No, this is my scene.”’ Claire Bloom, too, felt that ‘some of his gags may even have been a little too incandescent for Chaplin because, laugh as he did at the rushes in the screening room, Chaplin didn’t see fit to allow them all into the final version of the film’.35

Chaplin evidently took particular delight in creating the wonderful pastiches of Edwardian music hall songs and acts. ‘Spring Song’ led into a charming patter act and dance with Claire Bloom, dressed in bonnet and tutu. In ‘Oh for the Life of a Sardine’ he perfectly parodied the vocal style of George Bastow, one of the last ‘lions comiques’ and creator of ‘Captain Gingah’. However, he must have found most satisfaction in ‘I’m an Animal Trainer’, for here, after more than thirty years of trying, he at last managed to introduce the flea circus routine he had first performed on the set of The Kid. Chaplin resisted the pleas of his assistants to add audience reaction and laughter on the soundtrack. He was (at the time, rightly) convinced that in a full cinema the audience would provide the necessary reaction, and that it would be authentic. He failed to foresee the possibility of the films being shown in thinly filled cinemas or, worse, on the television screen. Seen in these circumstances, with no laughter or acknowledgement of an audience’s presence, the sequences have a somewhat spectral and eerie quality – perhaps not entirely inappropriate since the songs are Calvero’s dreams or nightmares of past fame and failure. Eugène Lourié was present when the songs were filmed: ‘He was very demanding with himself, shooting the vaudeville songs. He’d say, “We’ll do it again. I can do it better than that.” Sometimes we would shoot fifteen times.’36

The last shot of the picture was made on 25 January 1952 and Chaplin immediately began cutting and assembling the film. The Blooms – very sad to forsake the family atmosphere of the film and the studio – left California on the Santa Fe Chief on 13 February.

Chaplin spent most of the next three months cutting and at the beginning of May ordered the rebuilding of several sets for retakes. At this point, yet another Chaplin joined the cast. Some of the new shots required Terry to be seen through the open door of Calvero’s apartment, and Oona doubled for Claire Bloom in these scenes. On 15 May, Chaplin showed a rough cut to James Agee and Sidney Bernstein,37 and was gratified by their reactions. By 2 August, the final prints were ready for a preview at the Paramount Studios Theatre, which held 200 people and on this occasion was packed. Sidney Skolsky, the celebrated Variety journalist, described the event two days later:

The guest list ranged from such celebrities as Humphrey Bogart to Doris Duke to several old ladies and men who had worked with Chaplin since The Gold Rush back in 1924 … Chaplin and his assistant, Jerry Epstein, ran the picture at two in the afternoon, because Chaplin wanted to check the print personally. Chaplin, who wrote, produced, directed and starred in the picture, had to do everything personally. He even ushered at this preview showing. Then when the lights in the projection room were off and the picture started, this little gray-haired man sat at the dial-controls in the rear of the room and regulated the sound for the picture. It was the most exciting night I have ever spent in a projection room …

There was drama and history in the room. There was comedy and drama on the screen, and there was a backdrop of drama running along with the picture Limelight itself …

The projection room lights went up. The entire audience from Ronald Colman to David Selznick to Judge Pecora to Sylvia Gable stood up and applauded and shouted ‘Bravo’. It was as if all Hollywood was paying tribute to Charlie Chaplin … Then the little gray-haired fellow walked up to the platform. He said: ‘Thank you. I was very scared. You are the first people in the world to have seen the picture. It runs two hours and thirty minutes. I don’t want to keep you any longer. I do want to say “Thank you –”’ and that’s as far as Chaplin got. A woman in the audience shouted, ‘No! No! Thank you,’ and then others in the audience took these words and shouted them to Chaplin … Somehow I think this is the key to Limelight. It doesn’t matter whether some people think it is good and some people think it is great. The degree doesn’t matter. This is no ordinary picture made by an ordinary man. This is a great hunk of celluloid history and emotion, and I think everybody who is genuinely interested in the movies will say, ‘Thank you’.

Chaplin had decided that the world première of Limelight should be in London and that he would take Oona and the children there for the occasion and a prolonged holiday afterwards. It would be Oona’s first visit to England. They planned to miss the Hollywood press show and the New York opening, and left California on the first lap of their journey on 6 September. The night before, Tim Durant gave a send-off clambake party for them at his home. The guests included Artur Rubinstein and Marlon Brando, who was the only one who arrived in a dinner jacket. Chaplin thrilled them with an outstanding party piece, a dance with Katharine Dunham38 in which he perfectly reproduced and reflected her mannerisms, personality and grace. But Charles Junior sensed that his father was preoccupied, and the following day, when Tim Durant drove Chaplin and Oona to Union Station, Chaplin told him that he had a premonition that he would not return.39

The Chaplins arrived in New York on the Santa Fe Chief with Harry Crocker, who was to accompany them to Europe to take charge of publicity, on 9 September. A week later they were joined by the four children, accompanied by their nurses, Edith McKenzie (‘Kay-Kay’) and Doris Foster Whitney. The week in New York was somewhat restricted. Chaplin’s lawyer had warned him that a suit was in process against United Artists and that an attempt might be made to serve a summons on him, which could frustrate the entire trip. Chaplin, not for the first time, had to stay in hiding, though he seems to have left the Sherry-Netherlands Hotel on one or two occasions at least. Edith Piaf was playing in New York and says in her memoirs that Chaplin came to see her performance and visited her backstage.

At Crocker’s urging Chaplin attended a lunch with the editorial staff of Time and Life magazines, an event he found frigid and unfriendly and which failed to achieve favourable notices from the magazines. He also attended the New York press show of Limelight. There was no repetition of the open hostility of the Verdoux press conference, but Chaplin found the atmosphere at the show uneasy and unfriendly. He was gratified, however, by many of the subsequent reviews.

On Wednesday, 17 September 1952, the Chaplin family embarked for England on the Queen Elizabeth. Still evading the process-server, Chaplin boarded the ship at five in the morning and did not dare show himself on deck. Consequently, the devoted James Agee, who had come to see him off, failed to see him as he waved his hat feverishly out of a porthole. Chaplin and Agee were never to meet again: the critic died a couple of years later from a heart attack. Once at sea – process-servers left behind – Chaplin experienced a sense of freedom. He felt like another person. ‘No longer was I a myth of the film world, or a target of acrimony, but a married man with a wife and family on holiday.’40

The Queen Elizabeth had been at sea two days when the radio brought extraordinary news. The United States Attorney-General, Judge James McGranery, had rescinded Chaplin’s re-entry permit and ordered the Immigration and Naturalization Service to hold him for hearings when – or if – he attempted to re-enter the country. These hearings, he said, ‘will determine whether he is admissible under the laws of the United States’. The Justice Department added that the action was being taken under the US Code of Laws on Aliens and Citizenship, Section 137, Paragraph (c), which permitted the barring of aliens on grounds of ‘morals, health or insanity, or for advocating Communism or associating with Communist or pro-Communist organizations’. The Attorney-General said that this course of action had been planned for some time but that he had waited until Chaplin had left the country before acting. Chaplin, in other words, had no longer the right to return to the place which for the past forty years he had made his home, and to which he had attracted so much love and lustre.

The Attorney-General’s action followed a month of urgent negotiation between the Justice Department and the Immigration and Naturalization Service, which had begun when a Mr Noto of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) telephoned the FBI on 25 August to say that Chaplin was intending to sail for England in September.

Mr Noto’s information seems to have led to a meeting on 9 September between Edgar J. Hoover and the Attorney-General, who had been appointed to the post only five months before by President Truman, anxious to counter McCarthyist charges that his administration was ‘soft on Communism’. Judge McGranery was a devout and politicized Roman Catholic, nominated by Pope Pius XII, over the years, as Knight Commander of the Order of St Gregory, Knight of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem and Private Chamberlain of the Cape and Sword.41 At the Department of Justice he ‘expanded the internal security section of the department’s criminal division’.42 As a special assistant he appointed Roy Cohn, who was to become more famous, and latterly infamous, as right-hand man to Senator Joseph McCarthy. McGranery told Hoover that he ‘was considering taking steps to prevent the re-entry into this country of Charlie Chaplin … because of moral turpitude’. The files on the Barry case were turned up again: ‘See that all is included in memo to A.G.,’ scribbled Hoover.

On 16 September, Hoover informed the Los Angeles office that Chaplin had been issued with a re-entry permit and that they should advise head office of any information on his tour abroad. A note at the foot of the message comments, ‘INS has advised that even though he was given a re-entry permit, this permit gives no guarantee he will be allowed to return to the United States.’ This was to be confirmed by McGranery’s announcement of 19 September.

The FBI files reveal how dubious was McGranery’s action, and how nervous were the Immigration and Naturalization Service about their position in the matter. At a meeting on 29 September between an FBI supervisor and three officers of the INS: