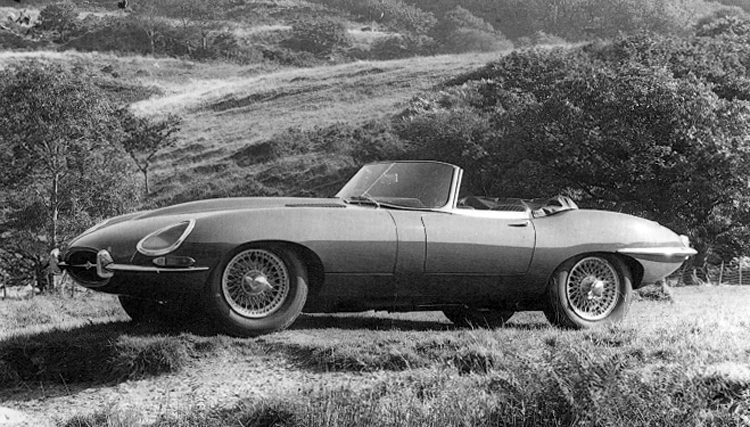

The 1962 3.8-litre roadster with the hood raised. Many E-types of the day carried their registration number on the bonnet which was less aerodynamically-instrusive than positioning it below the air intake.

‘It is not often that I use the word “fabulous” about a car, but the “E” type fully deserves that description.’

Today it is difficult to imagine the impact the E-type made on its announcement at the 1961 Geneva Show. Here was a race-bred, visually sensational, 150mph (241kph) sports car that was indisputably a Jaguar and, consequently, looked like nothing else.

The new car was slightly shorter, at 14ft 7.3in (4.45m), a good 5cwt (254kg) lighter and, above all, faster than the XK150 it replaced. But in the best Jaguar traditions, it was perhaps the E-type’s price which caused the same sensation that had greeted the S.S.1. back in 1931! The open two-seater was priced at £2,097 while the fixed-head coupe was £99 more at £2,196. This made it, in theory at least, the fastest car on the British market with its nearest rival, the Aston Martin DB4, selling for £3,968, or at about twice its price. However, on the all-important American market, the principal competition came from General Motors’ newly introduced glassfibre bodied 5.3-litre Chevrolet Corvette, which sold for $4,038 in open form on its home territory, while the equivalent E-type was a good $1,500 more at $5,595.

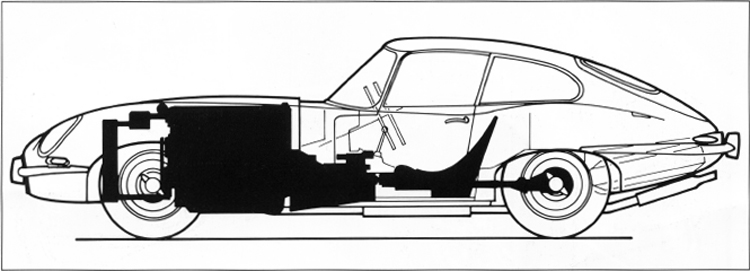

The E-type’s origins were all too obvious to anyone familiar with the D’s construction, though the central monocoque was of steel, rather than magnesium alloy and was completely different in detail. The stressed centre shell was built-up .almost entirely of 20 gauge sheet steel, produced for Jaguar by Pressed Steel, and welded together. At its forward end the scuttle was strengthened by a horse-shoe-shaped surround with its ends joined to deep, hollow sills. These, in their turn, were attached at their extremities to a strong hollow member, which ran across the car just ahead of the rear-suspension. There was, in addition, a deep transmission tunnel and this, along with a square section transverse member mid-way along the sills’ length, formed a link between the scuttle, floor and sills. There were additional top hat sections which were effectively perpetuated on the boot floor, and also provided a mounting for the independent rear-suspension. This extremely rigid structure was further reinforced by the curved body panels. The cockpit area was so strong that it could be retained, without further reinforcement, for the open version of the E-type.

The engine, transmission, front-suspension, steering-rack and big, forward-opening bonnet were carried on a framework of square section Reynolds 541 tubing. The sub-frame proper was made up of three sections: two side assemblies and a front transverse one. The separate structures were welded together but then bolted to form the whole. In turn the sub-frame was bolted to the hull at eight points, with three or four bolts apiece. A lesson learnt from the D-type was that this greatly simplified repairs. The bonnet was made in three sections with the joints concealed by a chromium-plated moulding. Although the front-suspension of unequal wishbones and longitudinal torsion bars was similar to that used on the E’s XK150 predecessor, in detail it more closely followed that of the D-type. Consequently the bars were mounted in inner extensions rather than in the wishbones’ pivots. The bars could bend slightly, as well as twist, the advantage being that they could be removed without disturbing the rest of the layout.

The 1962 3.8-litre roadster with the hood raised. Many E-types of the day carried their registration number on the bonnet which was less aerodynamically-instrusive than positioning it below the air intake.

A rear view of the 1962 3.8. The chrome stripping running along the top of the doors was initially peculiar to the open E-type though was also later applied to the 2+2 of 1966.

The E-type’s unique body structure is clearly shown in this photograph. There is a strong central tub with a triangulated sub-frame to which the engine, gearbox and front-suspension units were attached.

As far as the all-important independent rear-suspension was concerned, it was still a relatively rare facility on British cars of the day. Development work was undertaken on a Mark II saloon which showed a reduction of 1901b (86kg) in unsprung weight, compared with a solid axle. The principal difference from this layout, and that of E2A of the previous year, was that it was embodied within a self-contained fabricated steel bridgepiece which could be removed complete from the car. The Salisbury 4HU hypoid bevel gear incorporated a Powr-Lok limited-slip differential, the casing being rigidly bolted to the top and sides of the bridge.

The Dunlop disc brakes were mounted inboard adjoining the casing while the tubular drive shafts, universally mounted at both ends, also formed the upper-suspension links. No sliding joints were employed. Transverse loading was catered for by the use of taper roller bearings at both ends of the shaft, with the hubs housed in light alloy castings which also extended downwards to provide a pivot point for the lower links below, and parallel with, the half shafts. These were formed of single tubular members of approximately 2.5in (63mm) external diameter. An anti-roll bar connected the two. Each lower link was sprung by twin coil springs, each containing a Girling telescopic damper. Twin, rather than single springs were employed as they took up less space than a single unit and would not intrude into the already limited luggage area.

The E-type’s self-contained independent rear-suspension system shared, in essence, with the contemporary Mark X and the later XJ saloons. Note the inboard disc brakes, aluminium wheel carriers and anti-roll bar.

The entire suspension unit was attached to the body structure by rubber bushes matched to angularly-placed V-shaped rubber saddles, two at each side, which secured the suspension unit to the cross member of the hull. The anti-roll bar mountings and the longitudinal radius arms were also rubber mounted. Consequently there was no metal-to-metal contact between the unit and the body, and the E-type driver was isolated from high frequency transmissions and road vibrations. In addition, the rubber mounting permitted the radius arms to slightly expand and contract along their length. They also allowed a controlled degree of a rotational movement of the axle casing, in reality a maximum of 5deg under driving torque and 3deg under braking. This was approximately the same as a cart-sprung live axle and provided a cushioning effect aimed at eliminating transmission shudder.

The E-type’s engine was the familar XK six-cylinder twin overhead camshaft unit of 3,781cc, which had first appeared in the XK150S of 1959 and developed 265bhp at 5,500rpm. Running in seven bearings, the substantial crankshaft was produced either by Smith-Clayton Forge of Lincoln or Scottish Stampings of Ayr. The cast-iron cylinder block was the work of Leyland Motors of Leyland. Leyland Motors had been responsible for it from the engine’s 1948 appearance and it thus pre-dates that company’s motor industry involvement culminating, in 1968, in its ownership of the British Motor Corporation, which by then included Jaguar. The aluminium cylinder head was also twin-sourced, being produced either by West Yorkshire Foundries of Leeds or William Mills of Wednesbury, Staffordshire. Valves operated at an included angle of 70 degrees in the ‘straight port’ type of head introduced in 1958. There was a 9:1 compression ratio. Triple SU 2in (50mm) HD8 carburetters were employed, having been evolved by the redoubtable Harry Weslake.

William Heynes was to comment of the layout: ‘This system has proved extremely satisfactory both for maximum power and even distribution at low speeds … care has been taken to make all passages as nearly as possible the same length and, more important, they all have the same flow.’ This was also an aid to economic fuel consumption. The Motor achieved an average of 19.7mpg (37.1kpl) when it first tested the E-type, and owners found 18mpg (28kpl) not uncommon.

Much was made of the fact at the time that the new Lucas SFP pump was located within the rear-mounted 14-gallon (63.6-litre) petrol tank. The pump was of the constant running type, the idea being to supply fuel at a controlled rate to the carburetters. Any fuel surplus to requirements was bypassed back to the tank. It was so designed to prevent vapour lock problems, the flow not being susceptible to under-bonnet and engine heat, by eliminating vacuum on the suction side and maintaining a constant pressure in the petrol pipes.

The decorative bar containing the Jaguar motif ahead of the air intake makes an essential visual contribution to the front of the Series I E-type.

The hood lowered to reveal the tops of the original bucket seats, which were a major feature of the 3.8-litre cars.

Equally novel was the electrically-operated, energy-saving cooling fan. Also of Lucas manufacture, the 3 GM unit cut in by a thermostatic switch in the header tank which switched on when the water in the 1.37 gallons (6.25 litres) cooling system reached 80°F (27°C) and out when the temperature dropped below 73°F (23°C). The cowled, slender, two-bladed fan ran at around 2,300rpm and consumed 6 to 7 amps. Like the D-type, the header tank was located separately, and behind, the Marston Excelsior cross flow aluminium radiator which permitted a low bonnet line. At the other end of the engine a hydraulically operated 10in (254mm) single plate Borg and Beck clutch was employed. The gearbox was a four-speed Moss unit, with synchromesh on second, third and top gears.

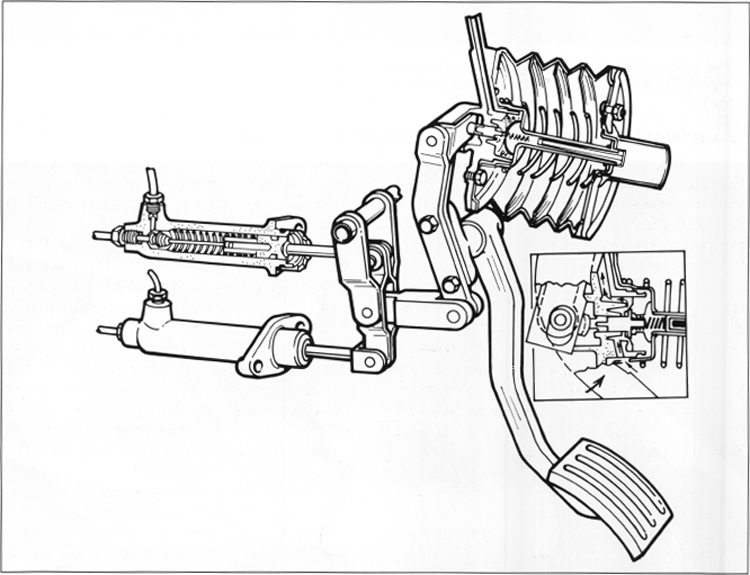

All round disc brakes were fitted, 11in (279mm) diameter at the front and 10in (254mm) at the rear. Twin master cylinders were employed so that, in the event of a hydraulic failure of the front brakes, the rear ones could still be applied and vice versa. This layout was made possible by the use of an American Kelsey Hayes servo, made under licence by Dunlop. It was an unusual system which applied mechanical pressure to the master clyinders, rather than providing the usual in-line boost of the conventional system which had been successfully employed both on the big Mark IX and smaller Mark II models. Centre lock 72 spoke Dunlop wheels with 6.40×15 RS5 cross ply covers from the same manufacturer were fitted, though 6.00×15 front and 6.50×15 rear R5 racing tyres were available, with appropriate wheels, at extra cost.

Both the roadster and coupe were uncompromising two-seaters: there was no provision for carrying children. Luggage space was certainly limited in the shallow boot of the open car though there was considerably more in the coupe, which was sensibly fitted with a rear opening door. The roadster could later be had with a detachable glassfibre hard-top, costing an extra £76, which, conveniently, could be fitted with the hood still in place.

The car was well instrumented with white-figured, black-finished Smiths oil pressure, water temperature, fuel and ammeter. These were all located in a centrally-mounted, aluminium-finished panel, which was echoed on the handbrake lever shroud. The matching, but larger, rev counter and speedometer were directly in front of the driver. The Coventry Timber Bending Company, whose association with Jaguar went back to its D-type days, was responsible for the wood-rimmed, three-spoked steering-wheel, with the column being adjustable for both rake and reach. Consequently the seats were non-adjustable but trimmed in Connolly hide with the floor being well carpeted. Visibility was good, thanks to thin pillars, while in wet weather the triple-armed, two-speed windscreen wipers coped with the curvature of the windscreen. Progressively, washers were fitted.

The famous XK engine was used in the E-type in triple-carburettered 3.8-litre state, as introduced in the XK150S of 1959, and enlarged to 4.2 litres in 1964. It is shown here in competition form on the Browns Lane test-bed during the 1960s. From left to right: Harry Mundy, Walter Hassan, William Heynes and Claude Baily.

When Jaguar introduced its successor to the XK150 in 1961, it was called the E-type in Europe and the XK-E in America.

But why E? To find the reason, we must return to the 1948 Motor Show when Jaguar’s new sports car made its sensational debut. It was the first recipient of Jaguar’s new 3.4-litre twin overhead camshaft engine and the model’s XK120 name echoed, firstly, the designation accorded to its engine and, secondly, reflected its top speed, which was a very impressive figure for the day.

When the firm entered the Le Mans 24-hour race with a purpose-designed sports-racer, the C-type, in 1951, it was designated as the XK120C, the suffix simply standing for Competition. The D-type name had arrived unofficially in the Jaguar competition shop for no other reason that it was the next letter in the alphabet after C! However, the first six ‘D’ types, chassis numbers 401 to 406, all carried the XKC prefix and the car was originally designated ‘XK120C Series IV.

Harold Hastings, Midlands editor of The Motor, claimed to have been the first to refer to the D-type in print. There is no mention of the car by name, however, in his High Speed Impressions of the New Jaguar, following a run with Norman Dewis at MIRA in prototype OVC 501 and recounted in The Motor of 2 June 1954, though his Le Mans report (16 June) refers to “… three 4.9-litre Ferraris fought it out with three of the new D-type [my italics] 3.4-litre Jaguars’. However the rival account in The Autocar makes no reference to the designation.

When work began on a road-going version of the D, what else could it be called but the E? One of the earliest references to it came from Malcolm Sayer, whose paperwork refers to the ‘E-type Prototype’.

The name survived into production but Jaguar’s American subsidiary wanted the new model called the XK-E, to reflect continuity with the earlier XK sports car range and to stress its twin-cam engine. Browns Lane, with some misgivings, agreed.

So much for the car’s specifications. But how was the E-type received by the motoring press? At this time in Britain this meant the two influential weeklies, The Autocar and The Motor and the monthly Motor Sport. All had the opportunity to sample the E-type prior to the car’s official launch at the Geneva Show on Wednesday 15 March 1961, with the weeklies able to take their cars for continental tests. Motor put a roadster registered 77 RW – and the second E-type to be built by the production department – through its paces while Motor Sport and The Autocar had a gun-metal grey left-hand drive fixed-head coupe, registered 9600 HP, which was a pre-production example and, in fact, the second fixed-head coupe prototype to be built. The roadster ‘only’ managed 149mph (239kph) though the coupe achieved the magic top speed of 150mph (241kph), probably on account of its superior aerodynamics and lack of front bumper overriders! But in reality, these speeds were never attained by the production cars.

The 72 spoke Dunlop wheels. This pattern endured until 1967 when they were replaced by a similar but more robust design.

The 3.8’s rear combined rear-light and flasher unit. Although outwardly similar to those fitted to the coupe version, they are not interchangeable because of the different curvature of the bodywork.

The 3.8’s headlamps cannot be considered a strong point and were greatly improved by the arrival of the sealed-beam units of the 4.2-litre cars.

In March 1982, twenty-five years afterwards, Maurice Smith, The Autocar’s editor from 1955 until 1968, took readers on a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse in an article for that magazine, when he recounted the famous occasion. The car, chassis number 885002, ‘… chosen for our test was the very well loosened up LHD second prototype coupe… Chosen may not be the right word since Jaguar used to develop on a shoestring and it was the only coupe.’ Smith was the first to recognise that to ‘… achieve 150mph maximum, the 3.8-litre engine had to be a very good one. The necessary power was conjured-up during prolonged work on the test beds, the engine being pulled out and reinstalled more than once.’ The figures were achieved on an 8.7-mile (14km) straight and level stretch of pinewood-flanked motorway south east of Antwerp ‘… which led nowhere and was virtually deserted’. Today it is part of the E39 running from the outskirts of the city to Herentals. Smith also revealed that he ‘… later happily ran a 3.8 roadster as an everyday car. It went to London four or five times a week, rusted slowly and never, to my knowledge, exceeded 137mph (220kph).’

But now to the test which appeared in The Autocar of 24 March 1961, in the week following the car’s announcement. Note that the principal complaints of the limitations of the gearbox, high oil consumption, poor seating and indifferent lights were all rectified with the arrival of the 4.2-litre car in 1964. But clearly the magazine was in no doubt about the E-type’s ‘outstanding feature’ which was ‘… the performance of this car … best studied by reference to the formidable list of acceleration figures. They are the best so far recorded, in almost any part of the range, in an Autocar road test. The normal limit for engine speed of 6,000 rpm was never exceeded during measurement of acceleration.’

| ROAD TEST Jaguar E-Type Coupé |

| Reproduced from Autocar 24 March 1961 |

For standing start figures the clutch was engaged at about 2,000r.p.m. and gear changes were made at about 5,800r.p.m. In this way a mean of 14.7 seconds was obtained for standing quarter-mile, and as examples, 0–60 m.p.h. took 6.9sec and 0–120 m.p.h. only 25.9sec. Up to 90 m.p.h. all speed increases of 20 m.p.h. were achieved in under 6 sec.

Given super premium (100 octane) fuel, there is an exceptional flexibility in top gear. It has smooth pulling power from little more than 10 m.p.h. straight up to 140 m.p.h. and more. Between 50 m.p.h. and 130 m.p.h. in this gear the acceleration is quite breathtaking, and if even more is desired there is third gear, which will pull comfortably from standstill to 116 m.p.h. Where instant tremendous response is desired from walking pace – on leaving an area of heavy traffic, perhaps – there is a much lower second gear which will take the car up to 78 m.p.h.

Bottom gear will be used instinctively by most drivers for moving off from a standstill, although it is not really required except on a hill, but unless care is taken in selecting when at rest it is easy to slip into reverse – at traffic lights, for example. The gear lever itself is short and well positioned and the box functions smoothly and silently in the three upper ratios. These same ratios, which are rather stiff to select, engage cleanly so long as relatively slow changes are made – the synchromesh being somewhat feeble – although such leisurely changes are scarcely in keeping with the car’s character. The only vibration noted at any time was noted on the overrun, and apparently it arose from the transmission.

The fixed-head coupe E-type, the fifth coupe to be built, receives plenty of attention on its announcement at the 1961 Geneva Show.

Contributing considerably to the remarkable acceleration figures is the new independent rear suspension used with a limited-slip differential and inboard disc brakes to give low unsprung weight. Together they give road adhesion, with freedom from wheelspin, of an order seldom experienced before.

This new independent rear suspension, used in conjunction with a front layout of similar geometry to that of the previous D-type, has provided all that a driver could hope for in such a car. There is no harsh movement in any plane and roll is negligible. The ride is relatively soft and even bad Belgium pavé can be taken with no more than a rumble and slight pitching, but for the occupants scarcely a jolt or shake. At all speeds, movement arising from road irregularities is damped out at once, and there is not even a suggestion of the float sometimes experienced with soft suspensions. The exceptional tenacity to the road of this car is one of the factors which will contribute to the confidence of an average driver in using the high end of the car’s performance.

Fuel consumption is modest in view of the performance of the car – owing no doubt to a combination of excellent aerodynamic shape, high gearing and fairly low weight (24cwt). The fuel tank holds 14 gallons (64 litres); there is no reserve, but a warning light is provided. Fast road driving returned a journey average of 18.1 m.p.g., and a 137-mile trip in England, using up to 100 m.p.h., gave a 19.5 m.p.g. average. Maximum speed testing raised the consumption to 16.1 m.p.g. and increased the oil temperature and consumption also. This test car, the engine of which had done a great deal of bench and road running, had an abnormally high oil consumption of 650 m.p.g., amounting to about three times that of similar engines previously tested.

What the other drivers would get used to seeing: the rear view of the E-type fixed-head coupe at Geneva in 1961.

Good under-bonnet accessibility made possible by the forward-opening bonnet is one of the E-type’s strong points. The inlet side of the 3.8-litre engine with triple HD8 2in (50.8mm) SU carburetters, air box and air cleaner is much in evidence.

At 140 m.p.h., the car seems in one sense to be clinging to the road, so stable is its progress, yet in another sense it feels to be flying over it. Jaguar engineers are to be congratulated on their success in insulating the car from road, suspension and transmission noises which are so often transmitted to the interior of all-independent suspension coupés of this nature.

The rear drive and suspension assembly is carried in a detachable sub-frame, supported on vee rubber mountings in the body frame.

One of the successful compromises in this design is found in the clutch, which is smooth and progressive in take-up, yet bites with the minimum of slip for a rapid getaway.

Shorter pedal travel would be an improvement.

The braking system has twin cylinders and slight servo assistance for the four Dunlop discs. Pedal pressures at the lower speeds seem high, and, when cold, the brakes give the impression of being less effective than they are. Yet at very high speeds both check braking and heavy stopping power are excellent. When measuring retardation for various pedal pressures an improvement of about 25 per cent was noted when the brakes were hot, compared with the first recording with cold brakes…

The brakes may be applied hard at 120 m.p.h. or even higher speeds and the retardation is then smooth and very powerful, the car remaining under full control without deviation from its heading. Here the balance (including the selection of pad materials) has been struck in favour of high-speed require-ments, and until a servo can be devised to provide lighter pedal pressures at low speeds, without in any way altering the characteristics above about 80 m.p.h., the present system is perhaps as good a compromise as can be obtained for such a wide speed range.

The E-type’s XK engine is revealed in its full glory in a way that was never possible with its more enclosed XK Series predecessors.

The exhaust side of the same 3.8 engine. The dynamo was replaced by an alternator with the arrival of the 4.2 in 1964. The heater unit, complete with fan, is in the foreground.

What of the rack and pinion steering? It is light at all speeds and does not become heavy towards the full locks. With the recommended tyre pressures it is very positive and with pleasant, quick response to guidance or small corrective movements. For normal driving the balance is neutral with a suggestion of understeer. Up to the maximum of 150 m.p.h. the car holds an exact line and the steering wheel can be released momentarily at this speed without qualms.

Dunlop R.5 racing tyres, which are optional extras, were used for 700 miles of our 1,891-mile test, at home and on the Continent, including the maximum speed runs, when the pressure recommendations of 35 p.s.i. front and 40 rear were observed. Using these R.5 tyres, with their flat treads and firm shoulders, the car would ride across the central joints between lanes on the road with the minimum of weaving – a quality found only infrequently. On standard R.S.5s the joints were seldom noticed at all.

For most drivers the limiting factor in speed of cornering of this car will be their own skill. In extreme conditions there is the slight understeer which is desirable and can be amply balanced by the huge accelerative power always available. On greasy surfaces such as are found in towns, a light accelerator foot is essential with such immediate response and with so much power available; otherwise, sideways progress may result. On normal roads in rain the adhesion is excellent with R.S.5s – the standard equipment. If a skid is provoked, the steering permits instant correction.

Those of our drivers who became really familiar with this left-hand-drive E-type test car managed to get comfortable in it, but space is marginal, particularly with regard to leg and arm length. The knees will fit under the steering wheel if it is adjusted to suit them but then the wheel itself is rather too near the driver. We chose the low position for the wheel (which is adjustable for column length and angle) and splayed our knees a little. The pedals are close together, they do not have ideal pad angles, while the brake pedal also has a long travel.

Production cars will probably have seats of slightly different pattern from those in the prototype tested. They will be similar, however, in their roll-type cushions and slightly bucketed backs, both of which support the occupants firmly and comfortably. Headroom is greater than might be thought and no criticism is expected on this score. On the passenger’s side the toe board needs to be deeper (a small recess in the floor would help) for large feet.

A reasonably deep and amply wide, curved screen gives an uninterrupted forward view. The screen pillars are scarcely noticed and only to rearward is the driver’s outlook limited, though not to an important extent. If luggage is to be piled on the deck behind the seats, external mirrors will be needed.

Trouble has been taken to develop a three-blade wiper assembly which, with the aid of two-speed operation, keeps the screen clear in steady rain over nearly all its width up to about 110 m.p.h. The headlamps, buried behind fairings, are powerful and adequate for up to 100 m.p.h. on a motorway at night, but in mist or fog there is a good deal of stray light due to refraction, which proves very trying. An auxilliary lamp could be fitted in the air intake, which, we are told, is of larger area than is needed to keep the engine cool. The attractive steering wheel with light natural wood rim may have to be altered because of the reflections it causes in the windscreen. Otherwise the subdued instrument lighting and absence of small reflections make for restful night driving.

In the interests of standardization and therefore of economy, several interior features and fittings – in particular the recessed central switch panel – are similar to those of the Series II saloons. A speedometer graduated to 160 m.p.h. and a matching r.p.m. indicator, are placed in front of the driver. Ahead of the passenger is a tiny open glove compartment and there is a grab handle across the corner of the panel and screen pillar. Flanking the central panel are a manual choke lever, and twin heater controls. Plenty of heat is provided, but cold air ventilation in hot climates may prove inadequate. It is not comfortable to drive fast with the windows fully open because of draughts, and on this prototype the glasses need more support in their intermediate positions to prevent rattling. The extractor windows behind the doors open on somewhat flimsy catches.

Generally speaking, the interior is very pleasing in its matt black trim – leather at the sides and rear, otherwise carpeting – with contrasting bright metal panels. A good feature is the soft felt design of the sun vizors, which are neat, safe, rattle-free, and may be swung round at right angles to give protection at the side windows. Indicative of the ‘gentleman’s G.T.’ nature of this car is the provision for a radio and speakers.

The roof has a light grey pile cloth lining, over a thin layer of foam rubber, and round the front and top frames of the windows, as well as above the windscreen, are firm, padded safety rolls. Noise and heat insulation are good and no leaks were discovered.

To form a low bulkhead for retaining baggage, the forward part of the luggage floor hinges up and bolts in the vertical position. Beneath this section is a useful trough for stowing books, handbags, gloves etc. Under the back area of this luggage floor are the petrol tank, to the left, with a small hatch giving access to the electrical connections for the new type immersed pump, the fuel gauge, and the spare wheel. Carried in this wheel is one of Jaguar’s special, circular fitted tool boxes. The rear door has no external handle: the main catch is released from the interior and the lid springs open on to its safety catch, which is then released from outside.

Access to the whole of the car ahead of the bulkhead is easy when the one-piece nose section of the body is hinged up and forward. It is not difficult to remove this section. It has a central safety catch and is secured by an over-centre fastener at each side.

With the introduction of their long-awaited E-type Grand Touring models, Jaguars make possible a new level of safe, fast driving. The car tested is the first of a new line; no significant extras were fitted to it and there are some 40 more b.h.p. available in highly tuned versions of the 3.8 engine. Critics will find precious little to complain about and competitors will be hard put to match any of the main talking points of performance, handling, ride comfort and price.

| ACCELERATION TIMES (mean) From rest through gears to: |

|

| 30 m.p.h. | 2.8 sec. |

| 40 m.p.h | 4.4 sec. |

| 50 m.p.h | 5.6 sec. |

| 60 m.p.h | 6.9 sec. |

| 70 m.p.h | 8.5 sec. |

| 80 m.p.h | 11.1 sec. |

| 90 m.p.h | 13.2 sec. |

| 100 m.p.h | 16.2 sec. |

| 110 m.p.h | 19.2 sec. |

| 120 m.p.h | 25.9 sec. |

| 130 m.p.h | 33.1 sec. |

| Standing quarter mile 14.7 sec. | |

| MAXIMUM SPEEDS ON GEARS (R.5 tyres) |

||

| Gear | m.p.h. | k.p.h. |

| Top (mean) | 150.4 | 242.1 |

| (best) | 151.7 | 244.2 |

| 3rd | 116 | 187 |

| 2nd | 78 | 125 |

| 1st | 42 | 68 |

The 3.8-litre’s driving compartment. The leather interior adds to the overall feeling of luxury.

The E-type’s wood-rimmed steering-wheel is an impressive feature of the Series I and II E-types. Note the aluminium-faced instrument panel of the early 3.8s beyond.

The magnificent lines of the 3.8-litre coupe are revealed in this photograph. It is visually outstanding because it appears as a total entity, rather than as a roadster with a tin top.

The 3.8-litre fixed-head coupe. This is a 1964 example and is outwardly very similar to the Series I 4.2-litre cars.

Sir William Lyons with an E-type roadster. Registered 77 RW, this car was the second E-type to be built by the production department and was road-tested by The Motor. The occasion was a rally held at the then Montagu Motor Museum at Beaulieu in June 1961, to celebrate Jaguar’s 30th anniversary.

Because of the shortage of cars, 9600 HP was taken to the Geneva Show where Sir William Lyons, who preferred the coupe’s appearance to that of the roadster, was photographed standing proudly alongside it. The venue was the Eaux Vives gardens near Geneva on Wednesday 15 March 1961, the day before the Show opened.

While 9600 HP was available for appraisal on a nearby circuit, another fixed-head coupe, the fifth to be built, formed the centrepiece of the Jaguar stand inside the exhibition hall. There was impressive coverage in the national press and both the British motoring weeklies were in accord that the E-type was the star of the show. The impact of the model and the buoyancy of the British motor industry, which was the third largest in the world and, in European terms, second only to West Germany in vehicle output, was reflected in The Autocar’s Geneva Show report which began: ‘Introduction of the new E-type Jaguar – remarkable in performance, appearance and price – and the showing of more makes of car than any other country, allow Great Britian to lay fair claim to pride of place at the 31st Geneva Show.’

Its Temple Press rival was equally enthusiastic. The Motor’s technical editor, Joseph Lowry, reported: ‘Tucked away in the corner of the exhibition building, which gets more and more vast each year, a solitary E-type Jaguar coupe is the exhibit which every visitor to the Geneva Motor Show wants to see.’ In addition to the car’s sensational appearance, Lowry pointed out the highly competitive price which was favourably received: ‘Nothing else which is on view can challenge Sir William Lyons’ new model at which such refined high performance is being … regarded with something close to incredulity.’

JAGUAR E-TYPE PRODUCTION 1961–1974

After this impressive reception, production took a little time to build up. By the end of March, only sixteen cars (ten roadsters and six coupes) had been built. This is probably an appropriate moment to pause and consider just how the E-type was manufactured.

The air intake, bumpers and enclosed headlights were essentially carried over to the 4.2 and would survive as an entity until 1967.

When the 3.8 was introduced, the bonnet louvres were originally made separately though they were soon incorporated into the pressing.

The transparent Triplex headlamp covers, initiated on the 3.8, were perpetuated on the 4.2 and survived until the arrival of the ‘Series I½’ in 1967.

This design of 72 spoke wire wheels was current from 1961 until 1967.

The E-type’s construction throughout its production life, showing the unitary hull and front framework.

Up until 1959 Jaguar’s Browns Lane plant was the firm’s only factory but the success, in particular, of the medium-sized saloon range resulted in the works, in Lyons words, ‘… bursting at the seams’. The Conservative government of the day was directing industry to expand, not in its industrial heartland, but in areas of high unemployment. It was a policy opposed, with some justification, by Lyons but then: ‘It came to my knowledge that the Daimler Company, which occupied a very fine site at Radford, within two miles of our existing factory at Browns Lane was up for sale.’

Jaguar bought Daimler in June 1960, paying its BSA parent £3.4 million for what was Britain’s oldest marque name. This purchase – Radford embraced approximately one million sqft (304,800sqm) – effectively doubled Jaguar’s floor space without the firm having to move from outside Coventry. This gave the firm the opportunity to reorganise its production facilities, and all machining and XK engine manufacture was concentrated at Radford. As a result, Browns Lane became solely concerned with car assembly though the trim shop remained there.

As in the case of the D-type, the E-type was essentially made in two halves: the rear cockpit area and all-important independent rear-suspension, and the triangulated front framework and engine and gearbox. The bodies were assembled on special jigs and Jaguar pioneered the use of carbon dioxide welding for some of this work, which resulted in a cleaner weld than had hitherto been possible. The rear seam, between the bottoms of the rear wings and the rear apron, was covered by slim, shapely bumpers while the front equivalents concealed the joint between the bonnet panels and front apron. In addition, a certain amount of hand-leading was necessary prior to the body being prepared for painting. This particularly applied to the joints between the sills and the rear wing and the bulkhead.

The disposition of the engine/gearbox unit in relation to the coupe body. Note that the steering-wheel is adjustable for reach.

The 3.8 E-type had a unique brake servo, a bellows type Kelsey Hayes system made under licence by Dunlop.

The bonnet is counterbalanced when open and its size highlights just how much it contributes to the overall length of the car.

Extended at both ends: the 3.8’s bonnet and rear-opening door.

The inlet side of the 3.8 engine. Unlike the later 4.2, which had its inlet manifold as a single casting, the 3.8’s are individual to each carburetter.

Where the oil goes! The filler cap in the exhaust cambox. Early 3.8s were notorious oil burners though the problem had been resolved by this time. The model has a 15-pint (8.5-litre) sump.

A Lucas electrically-powered windscreen-washer system was a feature of the E-type from the outset.

In the meantime, the front-suspension, steering-rack and, then, the engine and gearbox were fitted to the triangulated front frame. This unit was then attached to the body assembly on the production line and, finally, it was reunited with its combined bonnet/front wing assembly. Such was the amount of hand finishing which had accompanied the body’s construction, that this had to be rejoined to its original hull, otherwise the complete structure would not have properly fitted back together again.

But production only built up relatively slowly. Up until the middle of August 1961, output was almost exclusively concentrated on the roadster, with 372 examples built. Over the same period only eleven fixed-head coupes were produced. From thereon both body styles were regularly manufactured. By the end of the year, a total of 2,160 E-types (1,729 roadsters and 431 fixed-head coupes) had left Browns Lane.

Incredibly this figure was considerably in excess of Jaguar’s original estimate for total E-type production. It was initially thought that the new sports car would have limited appeal and only sell about 250 examples though this gradually rose to the 1,000 figure. Maybe the relative sales failures of the D-type and XKSS had cast a shadow but, thirteen years previously in 1948, Lyons had apparently been caught out by the success of the XK120 which first appeared with handcrafted bodywork. Thus the expensive body tooling was not ordered until after the model’s sensational launch. And so it was with the E-type. In view of the initially low estimate, it only began to rise to 5,000 after the car’s tumultuous Geneva reception. Abbey Panels, the Coventry company responsible for producing most of the exterior body panels only created cheap concrete tooling to form the appropriate shapes. It was only when the model was in production and looked like becoming a long-term success, that proper Kirksite metal tooling was laid down.

9600 HP, the second fixed-head coupe built, and the one road-tested by The Autocar. Front bumper overriders were deleted to help ensure that the magic 150mph (257kph) could become a reality. Alongside the car is 86 year old George Lanchester, Jaguar having become custodians of the Lanchester name through its purchase of Daimler.

This photograph of a rainy day at Browns Lane was issued to the motoring press in July 1961. It shows fifty-four right-hand drive roadsters being collected by dealers and distributors; the cars would probably be used for demonstration purposes.

The exhaust side of the 3.8 engine. Note that the front sub-frame is correctly painted the same hue as the body colour.

The 3.8-litre’s driving compartment viewed through the rear open door. The black-faced instrument panel replaced the original aluminium-finished one when the glove compartment was simultaneously introduced between the seats.

A study in elegance: the Coventry Timber Bending Company’s Jaguar associations went back to D-type days and this fine beech veneered steering-wheel was an impressive feature of the E-type from its 1961 inception until the Series II ceased production in 1971.

In its original 3 8-litre form, the E-type was cooled by a thermostatically-activated two-bladed fan which, in truth, was not up to the job.

The E-type’s six-cylinder XK engine and V12 unit were not assembled at Browns Lane but at Jaguar’s Radford factory, still known to older Coventrians as ‘The Daimler’.

Daimler, Britain’s oldest car maker, began automobile production in 1896 from its ‘Motor Mills’ in Sandy Lane, Coventry. Such was the demand for its costly, well built products, that in 1908 the company purchased an additional site in the Radford area of the city though, two years later, the firm was bought by armaments manufacturer BSA. During World War I a factory was established at Radford and, during the inter-war years, this plant was expanded. By 1937, the original Sandy Lane factory was vacated and subsequently destroyed during the Coventry blitz. Today a municipal bus depot covers the site.

The Radford plant was expanded when Daimler joined the government’s Shadow Factory scheme. This ‘Shadow’ became operational in 1937, fortuitously as it happened, for seventy per cent of the original Radford works were to be destroyed during the war. Munitions and armoured cars were manufactured during 1939–1945.

BSA had bought Lanchester in 1931 to broaden Daimler’s marketing appeal but production ceased in 1956. Daimler car manufacture re-started but its cars were out-dated, over-complicated and manufactured in a bewildering variety of models. These were the years of the vulgar ostentation of the ‘Docker Daimlers’ but Sir Bernard was ousted from the BSA chairmanship after a boardroom coup in 1956. His place was taken by Jack Sangster, who was subsequently approached by Lyons who had heard Daimler was for sale. Jaguar bought the firm in 1960 and today its name survives as an up-market version of the XJ6 saloon. With the purchase, Jaguar doubled its floor space, while Radford was also only 2 miles (3.2km) from Allesley. Engine production was transferred there, permitting Browns Lane to mainly concentrate on car assembly. Unlike other car makers, which were directed by the government to expand in areas of high unemployment, Jaguar alone was able to grow in its industrial heartland.

The model’s March debut meant that examples also had to be on show in America for display purposes. Four cars had been dispatched from the factory on 28 February, destined for New York. The E-type was duly launched at the New York Motor Show, which opened on 1 April and was subsequently well received by the American motoring press. Road and Track was the first with a full road test and appraisal of the E-type. Even though the magazine had a car for a relatively short time it extolled, with an appropriately Dickensian flourish: ‘The car comes up to, and exceeds, our great expectations.’ The road-holding, in particular, came in four fulsome praise and ‘… provided magnificient cornering over and around twisting mountain roads’. The E-type’s steering was considered to be close to the best ever experienced by Road and Track. But, on the debit side, there was some concern about the lack of interior space.

The 3.8-litre E-type roadster was available between 1961 and 1964. It initially sold for £2,098 but a drop in purchase tax, from twenty-five to fifteen per cent in 1962, meant that it cost £1,829, or £269 less, in the final year.

This shortcoming was echoed by Car and Driver, when it wrote that the car’s seats were ‘… an enigma. Provided that the occupant sat in the recommended position they were very comfortable… However, it’s only a matter of time before the squirming set in and we felt our back being drilled by the horizontal bead on the back seat.’ The E-type’s appetite for oil also alarmed the testers, as their car was consuming a quart of oil every 112 miles (180km) – which echoed The Autocar’s experience.

But the American magazine reserved its most stinging criticism for the E-type’s gearbox. The ageing Moss unit, which lacked bottom gear synchromesh, dated back to 1948 and the XK120. In an effort to improve quality, Jaguar had taken over its production but it clearly left much to be desired: ‘The transmission has such poor synchromesh that gears are never changed needlessly’, it revealed. ‘We feel that the gearbox is definitely not on a par with the performance of the car as a whole and about the kindest thing we can say for it is that we didn’t like it.’ The magazine could not see why it was not possible to adapt the D-type’s all-synchromesh gearbox as an interim measure until a suitable gearbox was ready.

It should not be forgotten that approximately eighty per cent of the 72,000 or so E-types crossed the Atlantic to be sold in America. One of the most significant and, indeed, underplayed facets of the Jaguar business, was the company’s subsidiary there, Jaguar Cars, Inc.

Like most British companies, pre-war Jaguar (or SS as it was) had barely bothered with exports. It was only after the war, with overseas sales geared to steel allocation, that Jaguar successfully invaded the American market. In 1947 the firm appointed Max Hoffman to handle its cars in the Eastern United States and, later, ‘Chuck’ Hornburg undertook a similar assignment in the West. But in 1952, Joe Eerdmans arrived in America and later directed Jaguar’s transatlantic sales, a position he held with distinction until his 1971 retirement.

Lyons had first met Johannes Eerdmans, a Dutchman, by chance during the war, while on holiday with his family at Woola-combe, Devon. The two became friends and Eerdmans subsequently became joint managing director of the De La Rue printing company but left in 1952 and decided to emigrate to America. Lyons read of his impending departure in the Daily Express, immediately contacted him and the pair met over tea at the Dorchester. Lyons asked Eerdmans to undertake a fact-finding mission to investigate Jaguar’s American sales organisation. As a result the Hoffman arrangement was expensively unscrambled; he had taken on Mercedes-Benz, Jaguar’s principal competitor, despite Lyons’ wishes, though the Hornburg association was to flourish. Two years later, in 1954, came the creation of Jaguar Cars North American Corporation in Park Avenue, New York just down the road from Hoffman’s prestigious showrooms. The firm subsequently evolved into the 32 East 57th Street-based Jaguar Cars Inc.

The arrival of the E-type was timed for both the Geneva Motor Show (March 1961) and the New York Show, which opened on 1 April. There it received a sensational response, mounting a momentum for E-type sales in America which only began to slow in the 1970s.

As far as production was concerned, the 150 cars a week mark was passed in March 1962, and by the end of the year, the first full twelve months of production, an impressive 6,266 E-types had been built, with fixed-head coupes out-stripping roadsters and 3,540 closed cars produced compared with 2,726 open ones.

Output dropped slightly in 1963 when 4,065 E-types left Browns Lane. This meant a total of 12,491 cars built in a mere 2½ years, making the E-type the best-ever-selling Jaguar sports car. The previous record of 12,055 cars was held by the XK120 though it took five years to reach this figure.

One of the 3.8’s limiting factors was its Moss gearbox, an ‘old warrior’ which endured until the arrival of the 4.2 in 1964.

But outstanding as the E-type was, some of its more obvious failings had become readily apparent. Some were rectified relatively easily. The car’s dipsomaniac-like oil consumption was largely resolved from the 1964 model cars by the fitment of new oil control rings and subsequently rubber insert valve guide seals were introduced. American E-type owners also found that their cars had a tendency to overheat, particularly in traffic, where higher temperatures exacerbated the problem. This was often the result of a recalcitrant radiator sensor unit. Owners also found the dynamo was unable to cope with demand, particularly when the car was stuck in traffic. The uncomfortable seats and limitations of the archaic Moss gearbox had also been noted.

A 1961 left-hand drive roadster is being flown to America. This is an early car, as indicated by the escutcheon covering the hole for the keyed bonnet lock. From October 1961, an internal mechanism was introduced to prevent bonnet shake.

Practically all these shortcomings were resolved when Jaguar unveiled its 4.2-litre version of the E-type in London at the 1964 Motor Show.