3 Refinement: from 3.8 to 4.2 Litres

‘The Jaguar E-type has been one of the World’s outstanding sports cars from the day it was first announced… In its latest form it is very near perfection.’

William Boddy in Motor Sport, January 1965

When the E-type’s capacity was increased from its original 3.8 to 4.2 litres, the stimulus was, once again, Jaguar’s all-important American market. It will be recalled that the E’s power unit and independent rear-suspension were essentially courtesy of the Mark X saloon, which appeared at the 1961 Motor Show. Not perhaps one of Sir William Lyons’ finest creations, it had the doubtful distinction of being one of the widest cars, at 6ft 4in (1.93m), that Jaguar has ever produced. Nevertheless, it sold better than its Mark IX predecessor, despite initial criticisms of high fuel consumption, poor power steering and inadequate seats. But Jaguar was up against the growing litres of the American V8 which grew untrammelled during the 1960s. So the saloon’s capacity was enlarged not, it should be made clear, with a view to upping its 120mph (193kph) top speed but to improve its low speed torque and, consequently, its acceleration. The E-type was to similarly benefit.

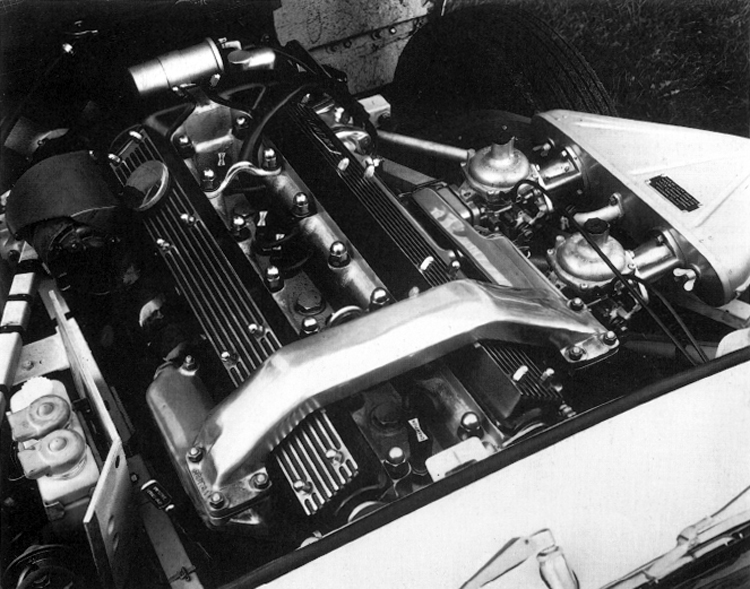

When it came to increasing the XK’s engine’s piston speed, which was 3,500ft per minute, it proved impracticable to enlarge the 106mm stroke without overloading the crankshaft. Instead the bore size was increased from 87 to 92mm. The only way in which the 5mm enlargement could be achieved, while retaining the dimensions of the block, was to Siamese all the bores. Consequently the centres of cylinders two and five remained unchanged but numbers three and four were moved closer together while one and six were relocated slightly outwards. Water circulation was also improved around the top of the bores. As the cylinder head remained the same, the hemispherical combustion chambers slightly overlapped the bores though this did not adversely affect the engine’s performance.

Re-positioning the bore centres meant that the crankshaft had to be redesigned and the opportunity was taken to increase the thickness, and thus the strength, of the webs which improved the shaft’s torsional stiffness. Considerable advances had been made in bearing materials since the XK engine was designed, those in the 4.2-litre engine were accordingly steel-backed, indium-flashed, copper-lead ones but were narrower than previously. The balance weights were also rearranged to reduce bearing loads. These modifications increased torque by ten per cent while maximum power of 255bhp was attained at 5,400 rather than 5,500 of the 3.8-litre power unit. Although the cylinder head remained unchanged, a new cast-aluminium water-heated inlet manifold was introduced, with an integral balance pipe, with a view to eliminating steam pockets.

There was also an all-important change to one of the engine ancillaries, for the dynamo that had hitherto been the norm was replaced by a Lucas 11AC alternator capable of delivering a full charge at only 910rpm, which meant that the battery was being charged while the engine was idling in traffic. The electrical system was accordingly changed to a negative earth one and a pre-engaged starter was also introduced. More powerful sealed beam asymmetric dip headlamps were fitted. Yet another improvement was the replacement of the tank submerged petrol pump by twin SU AUF 301 units. Also out went the original Kelsey Hayes bellows type vacuum servo to be replaced by a more conventional and ‘in-line’ Lockheed vacuum booster. It still operated a tandem master cylinder and the separate hydraulic systems were retained.

In addition to this enlarged power unit came a long-awaited all-synchromesh gearbox. This was a conventional unit with cast-iron casing fitted with Warner inertia lock baulk rings which prevented gear engagement before synchronisation was complete. An interesting historical aside is that the individual responsible for the design of this box was William G J Watson, creator of the short-lived and curious 1947 Invicta Black Prince (3-litre Meadows twin overhead camshaft engine and Brockhouse torque converter), and of the racing V12 Lagonda of the 1954–1955 era. Watson subsequently joined Jaguar.

At the same time as the long-awaited gearbox arrived, a Laycock Hausserman diaphragm clutch, which required a lighter pedal pressure than that of the 3.8, replaced the Borg and Beck unit.

Externally the 4.2-litre E-type – retrospectively titled, like its 3.8 precursor’, the Series I – looked identical to its predecessor. But internally, there had been a response to the criticisms of the original seats. Out went the buckets to be replaced by new pleated ones, which incorporated modest adjustments for rake. With these, the squabs were shaped to give more support under the passenger’s knees and a new system for springing them was introduced. It consisted of a diaphragm made up of rubber rings linked with wire clips and padded with foam rubber.

At the same time the aluminium-finished handbrake shroud was replaced by a leather cloth covered arm rest, with a hinged lid, which revealed a useful box for storing odds and ends.

So how were these important modifications received? In its issue of 31 October 1964, Motor magazine – it had dropped the definite article earlier in the year – reported on its test of a 4.2-litre coupe, registration number ARW 732B. It was in little doubt that the larger capacity engine and all-synchromesh gearbox had greatly improved the car’s refinement.

ROAD TEST

Jaguar E-type 4.2 |

Reproduced from Motor

31 October 1964 |

The new 4.2-litre supersedes the earlier 3.8 as the fastest car Motor has tested, with a mean maximum of exactly 150 m.p.h.; this marginal increase (less than 1 m.p.h.) stems from a higher axle ratio rather than more power, which remains at 265 b.h.p. (gross). The 10 per cent increase in capacity is reflected lower down the rev band by a corresponding increase in torque (from 240 to 283 lb. ft.) which, despite the higher gearing and greater weight, gives almost identical acceleration to our previous test car; with the lower (3.31:1) axle used before, there would be an appreciably greater strain on one’s neck muscles, which is severe enough now, 100 m.p.h. being reached from a standstill in well under 20 seconds. Using the lowest axle ratio, Americans will benefit from a better low-end performance while British and Continental buyers have improved steady-speed fuel consumption and even more relaxed cruising (100 m.p.h. corresponds to 4,060 r.p.m.) without any sacrifice in speed or acceleration.

The biggest improvement is the all-new, all-synchromesh gearbox. Gone is the tough, unrefined box that has accumulated a certain notoriety, in favour of one that will undoubtedly establish a correspondingly high reputation: although the lever movement is still quite long, it is fairly light and very quick, the synchromesh being unbeatable without being too obstructive. A good box by any standards and excellent for one that must transmit so much power.

Handling, steering and brakes are of such a high order that sensible drivers will never find the power/weight ratio of 220 b.h.p. per ton an embarrassment: indeed, this is one of those rare high-performance cars in which every ounce of power can be used on the road. The new seats are a big improvement but lack sufficient rake adjustment to make them perfect for all drivers. Nevertheless, 3,000 test miles (many of them on the Continent) confirm that this is still one of the world’s outstanding cars, its comfortable ride, low noise level and good luggage accommodation being in the best GT tradition.

Performance

Preconceived ideas about speed and safety are apt to be shattered by E-type performance. True, very few owners will ever see 150 m.p.h. on the speedometer but, as on any other car, cruising speed and acceleration are closely related to the maximum and it is these that lop not just seconds or minutes, but half hours or more, off journey times. Our drivers invariably arrived early in the E-type and the absurd ease with which 100 m.p.h. can be exceeded on a quarter mile straight never failed to astonish them: nor did the tremendous punch in second gear which would fling the car past slower vehicles using gaps that would be prohibitively small for other traffic.

From a standing start, you can reach the 30 m.p.h. speed limit in under 3 seconds, or the 40 m.p.h. mark in under 4 seconds, so it needs a wary eye on the instruments to stay inside the law. In either case, these speeds can be doubled in little over twice the times to whisk the car clear of other traffic at a de-restriction sign. From 30 m.p.h., it takes a little under 15 seconds to reach 100 m.p.h. and there is still another 15 m.p.h. to go before top must be engaged. Up to 90 m.p.h. any given speed can be increased by 20 m.p.h. in 4–5 seconds using third, and in 5–7 seconds using top. Low-speed torque and flexibility are so good that you can actually start in top gear, despite a 3.07:1 axle ratio giving 24.4 m.p.h. per 1,000 r.p.m. Driving around town, this fascinating tractability can be fully exploited by starting in first or second and then dropping into top which, even below 30 m.p.h. is sufficiently lively to out-accelerate a lot of cars. Before the plugs were changed half way through our test for a similar set of Champion N5s, prolonged low-speed town work caused misfiring when higher speeds were resumed, but a short burst of high revs in second gear would usually cure this fluffiness.

Motorway cruising speeds are governed by traffic conditions rather than any mechanical limitations; on lightly trafficked roads we completed several relaxed journeys at over 110 m.p.h. on the Italian Autostrada and Belgian Autoroutes. Not unexpectedly, hill climbing is remarkably good, top gear pulling the car up slopes (up to 1 in 5.2) that reduce many another to a second gear crawl. First copes easily with a start on a 1-in-3 hill.

All this performance is accompanied by astonishingly little fuss, the engine remaining smooth and mechanically quiet at all times. The electronic rev counter is an essential instrument, for the human ear could not detect that 5,500 r.p.m. was anywhere near the suggested limit of this magnificent engine. Even 6,100 r.p.m. – corresponding to 150 m.p.h. does not sound unduly strained.

Unlike other Jaguars, the E-type has a hand choke: cold starts are instant after a night out in the open and the engine pulls without hesitation or coughing, though on full choke (which is only needed momentarily) idling speeds are high. The new pre-engaged starter is much smoother and quieter than the old Bendix gear.

Running costs

At first sight, 18.5 m.p.g. sounds heavy but in relation to the performance this is an excellent consumption: many smaller-engined cars with nothing like the same performance can barely match it. Gentle driving will obviously improve the figure but not by any significant amount, as there is less than 4½ m.p.g. difference between the consumptions at a steady 30 m.p.h. and a steady 80 m.p.h. Good aerodynamics, high gearing and an efficient engine account for this unusually flat consumption curve. Only the very best British 100 octane petrol will prevent pinking at low r.p.m.: on the best Belgian, French and Italian brands, it would knock loudly if the throttle was not eased down progressively. At 5s 1d a gallon, fuel bills work out at £13 14s 6d per 1,000 miles at the overall consumption, and £118s at the touring consumption of 21.5 m.p.g….

At one time notoriously high oil consumption has been checked by new oil consumption rings to around 400 miles per pint.

Released by two inside catches, the enormous bonnet tilts forward to reveal the whole of the engine and front suspension; an alternator and new induction manifolding are obvious changes. Accessibility for routine maintenance is excellent.

Transmission

With the new gearbox in the 4.2, the slow deliberate change, weak synchromesh and awkward engagement of first are things of the past. Instead, a lightweight lever can now be whisked into any gear as fast as the hand can move, without beating the new inertia-lock baulk-ring synchromesh. First gear still whines but not nearly so loudly and it can now be used to advantage for quick overtaking; the other ratios emit only a faint audible hum. The new Laycock diaphragm clutch is much lighter than before and pedal travel reduced; although the movement is still quite long it is no longer essential to press the pedal to the floorboards when engaging first or changing gear. The clutch bites smoothly when moving off and will accept the brutality of racing changes without slipping and such is the low-speed torque that there is never any need to abuse the clutch for rapid take-offs, quick engagement at 2,000 r.p.m. giving the optimum results. High revs merely produce long black lines on the road, although we were always astonished at just how much power could be turned on without spinning wheels.

Jaguar have reverted to the high 3.07:1 axle ratio as standard equipment for the home and European markets since it gives the fast, relaxed cruising speeds that are legally possible on our motorways, auto-bahns and autostradas. North American cars, restricted in top-end performance by low speed limits, have a much lower ratio that gives a lower maximum but considerably better acceleration…

Brakes

Retaining the safety of twin master cylinders, the braking system now has a bigger servo which greatly reduces pedal effort. Our first E-type test car needed a 100 lb. push to record 0.96g: 60 lb. is sufficient on the 4.2 for 0.97g. There is also better progression and feel in the pedal, the disconcerting sponginess we recorded at low speeds before being completely absent in the latest car. A slight tendency to pull to one side marred high-speed stability under braking but otherwise the Dunlop discs on all four wheels felt immensely powerful and reassuring.

Although a severe Alpine descent made the discs glow bright red, there was always plenty of braking in reserve to stop the car easily without snatch or uneveness, if at rather higher pedal pressures. So long as the brake fluid is in sound condition, and of the right type, heat soak will not boil the hydraulics causing a complete loss of braking. This we confirmed after our standard brake fade test of 20½ stops at one minute intervals from the touring speed – a punishing 90 m.p.h. for the E-type. Pedal pressures increased a mere 10 lb. and pedal pressure was slightly longer towards the end of our test. Otherwise, the brakes were still true and very powerful – as we expected, for Jaguar’s own acceptance test is even more severe than ours at 30 stops from 100 m.p.h., again at one minute intervals …

Comfort and Control

We found the entirely new bucket seats a big improvement on the old, especially now that deeper foot wells and greater seat movement (two modifications made some time ago) have greatly improved leg room for tall people. A small swivelling distance piece at the base of the folding squab gives two rake positions but most of our drivers would have liked to recline still further: the backrest is rather upright and tends to support the back at shoulder height rather than at the base of the spine, unless you push back into the soft deep cushions. Even so, the driving position is generally good and one of our testers completed a one-day solo drive from Italy without any aches or discomfort.

An open throttle in the lower gears produces that characteristically hard, healthy snarl, yet cruising at 100 m.p.h. with the windows shut this is a particularly quiet and fussless car, wind and engine roar being unusually subdued. On a hot day sufficient cooling air can be admitted through open side windows which disturb the quietness at speed. Better heat insulation around the gearbox and transmission tunnel have lessened the problem of overheating in the cockpit but some form of cold air ventilation that by-passes the heater would still be a welcome refinement…

New sealed beam lights improve dip and main beam intensity but it is still essential to keep the covers clean, for their acute slope exaggerates any film of bugs and dirt which high-speed motoring inevitably collects. On a very good road, we found the lights just good enough for 100 m.p.h. but generally they are inadequate for fast driving after dark…

JAGUAR E-TYPE, 3.8-LITRE, SERIES I AND II (4.2-LITRE) SPECIFICATION

| PRODUCTION |

1961–1964

3.8-litre |

1964–1971 (2 + 2, 1966–1971)

4.2-litre |

ENGINE

| Block material |

Chrome cast iron |

| Head material |

Aluminium alloy |

| Cylinders |

In-line six |

| Cooling |

Water |

| Bore and stroke |

87×106m |

92.07×106mm |

| Capacity |

3,781cc |

4,235cc |

| Main bearings |

7 |

| Valves |

2 per cylinder; dohc |

| Compression ratio |

9:1 (8:1 optional) |

| Carburetters |

3 SU HD 8 |

| Max power (net) |

265 |

265 |

|

@ 5,500rpm |

@ 5,400rpm |

| Max torque |

2601b ft |

2831b ft |

|

@ 4,000rpm |

@ 4,000rpm |

TRANSMISSION

| Clutch: |

Single dry plate by hydraulic operation. |

| Type: |

(3.8) Four speedsynchromesh on top three gears.

(4.2) Four speed all-synchromesh.

Borg-Warner Model 8 option on 2 + 2. |

OVERALL GEAR RATIOS

| |

|

|

Automatic (2 + 2) |

| Top |

3.31 |

3.07 |

2.88/5.76 |

| 3rd |

4.25 |

3.93 |

|

| 2nd |

6.16 |

5.71 |

4.2/8.4 |

| 1st |

11.18 |

10.38 |

6.92/13.84 |

| Reverse |

11.18 |

10.38 |

5.76/11.52 |

| Final drive |

Salisbury hypoid, Powr Lok limited-slip differential |

| |

3.31 (optional 3.07

2.93, 3.07,

3.54) |

3.07 |

|

SUSPENSION AND STEERING

| Front: |

Independent, double wishbones, with longitudinal torsion bars, telescopic dampers and anti-roll bar. |

| Rear: |

Independent, with lower tubular links and fixed length drive shafts for transverse location, longitudinal location by radius arms. Two coils springs and telescopic dampers each side, anti-roll bar. |

| Steering: |

Rack and pinion. |

| Tyres: |

Dunlop 6.40×15 RS5 Dunlop 6.40×15 RS5 |

| Wheels: |

Dunlop wire 72 spoke. |

| Rim Size: |

5in. |

BRAKES

| Type: |

Dunlop discs front and rear, Dunlop servo assistance. (4.2)

Lockheed

servo. |

| Size: |

Front 11in; Rear 10in. |

DIMENSIONS (in/mm)

Track

Front: |

50/1.270. 2 + 2, 50.25/1,276 |

| Rear |

50/1.270. 2 + 2, 50.25/1,276 |

MAXIMUM SPEEDS

| Flying kilometre |

|

|

| Mean of four opposite runs |

150 |

m.p.h. |

| Best one-way time equals ‘Maximile’ Speed (Timed quarter mile after 1 mile accelerating from rest) |

150 |

m.p.h. |

| Mean of four opposite runs |

136.2 |

m.p.h. |

| Best one-way time equals |

137 |

m.p.h. |

| Speed in 3rd (at 5,500 r.p.m.) |

107 |

m.p.h. |

| Speed in 2nd |

78 |

m.p.h. |

| Speed in 1st |

51 |

m.p.h. |

ACCELERATION TIMES

| From standstill |

|

| 0–30 m.p.h. |

2.7 sec. |

| 0–40 m.p.h. |

3.7 sec. |

| 0–50 m.p.h. |

4.8 sec. |

| 0–60 m.p.h. |

7.0 sec. |

| 0–70 m.p.h. |

8.6 sec. |

| 0–80 m.p.h. |

11.0 sec. |

| 0–90 |

13.9 sec. |

| 0–100 |

17.2 sec. |

| 0–110 |

21.0 sec. |

| 0–120 |

25.2 sec. |

| 0–130 |

30.5 sec. |

| Standing quarter mile |

14.9 sec. |

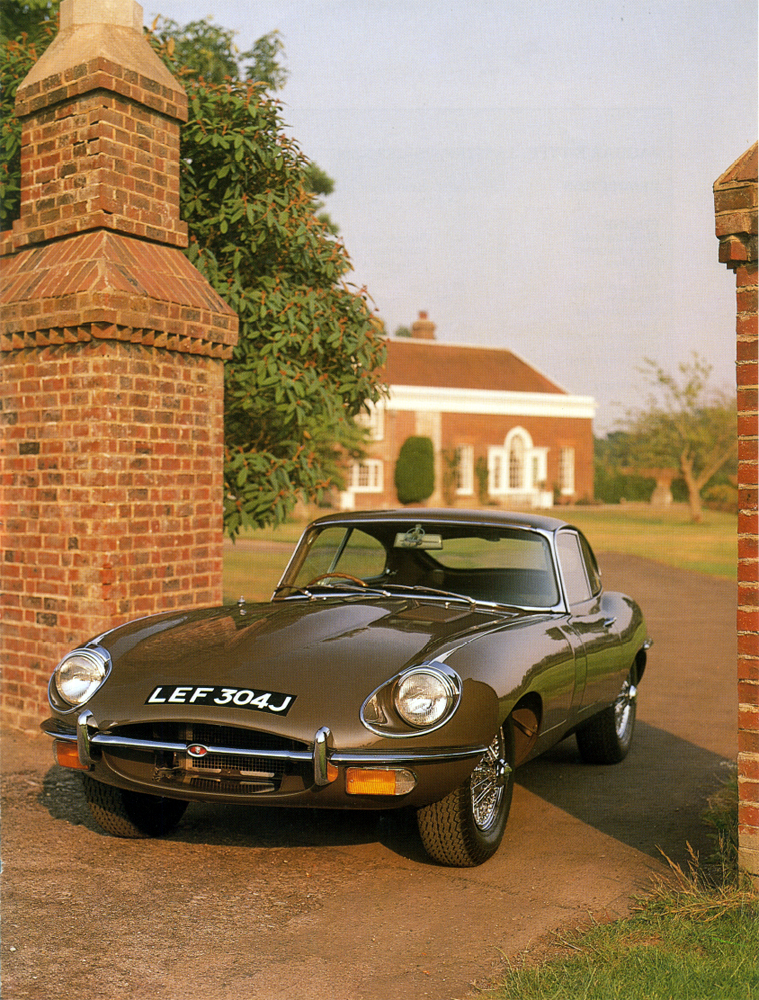

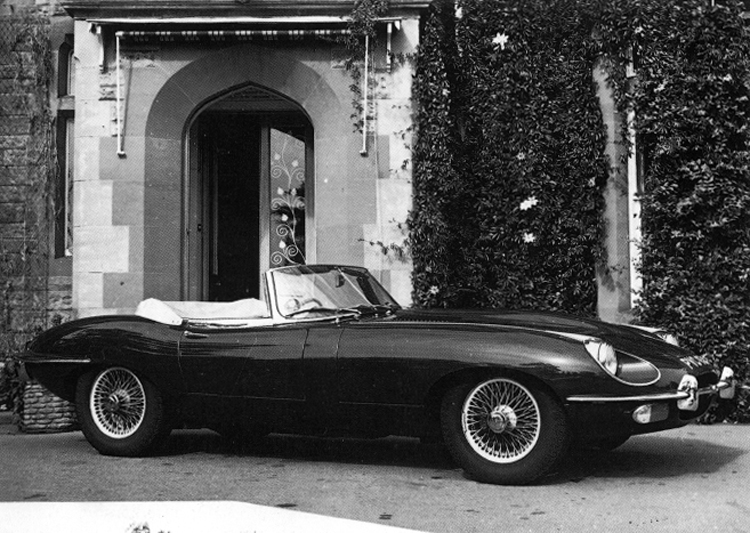

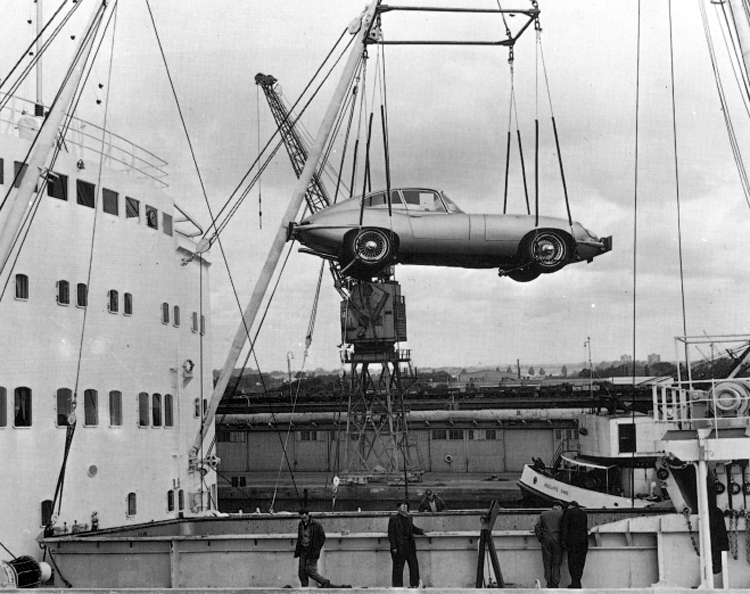

The public obviously liked the 4.2 E-type. In 1965, a record 5,294 cars were built and, in March of the following year, came a supplementary and popular variation in the shape of the 2 + 2 though, it has to be said, there was a dilution of those exquisite lines and some falling off in performance. The need for a longer E-type had been in Sir William Lyons’ mind since the model’s launch in 1961. As the car had been developed from the sports racing D-type it was, almost inevitably, an uncompromising two-seater. Since the model’s arrival however, increasing numbers of sports cars were being fitted with occasional rear seats for children, which Jaguar had first embraced back in 1954, when it had introduced them on the XK140. So an experimental car was accordingly built and delivered to Lyons’ Wappen-bury Hall home, which also provided an appropriate ‘domestic’ background for viewing experimental cars, as opposed to the usually drab factory one. In this instance, the embryo 2 + 2 was subsequently relegated to the stables at the Hall.

VARIATIONS ON THE E THEME

As Philip Porter reveals in his magnificent and monumental Jaguar E-type: The Definitive History (Haynes, 1989), in 1963 these thoughts were to fragment into three parts: the 2 + 2 proper, the XJ6 saloon and the XJ-S. Work on the prototype 2 + 2 E-type was undertaken by Bob Blake, who was responsible for the lines of the original coupe. The first prototype was completed by August 1964 and was followed by four experimental cars. The model proper was finally launched in 1966 though it had been intended for the 1965 Motor Show. But Autocar, in its issue of 27 August 1965, revealed that: ‘It will be a disappointment to many people here and in America to learn that the long-hoped-for expanded E-type exists but its introduction has had to be postponed indefinitely…’ Jaguar reluctantly took the decision not to announce the car in October at Earls Court because of the long-term effects which labour troubles have had in delaying production of existing models.’

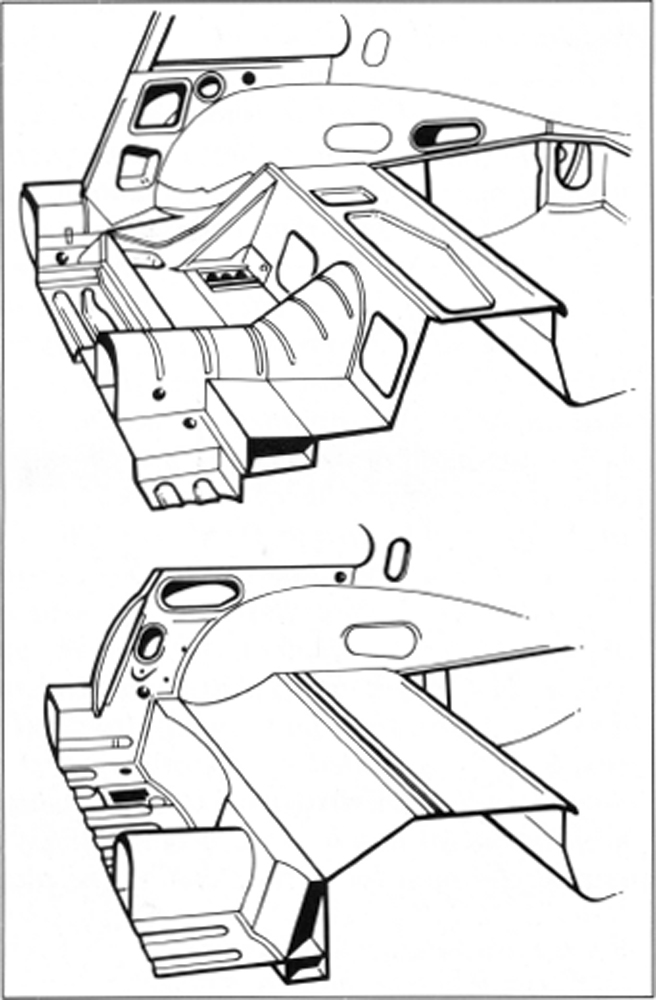

Structural Modifications

The 2 + 2 was available in coupe form only and the modification meant stretching the car’s wheelbase by 9in (228mm) to 8ft 9in (2.67m), which pushed its weight up 1.75cwt (63.5kg) to 27cwt (1,371kg), or about the same as carrying an extra passenger. In addition to the longer wheelbase, the coupe’s profile was midly altered. The windscreen was 1.5in (38mm) higher than hitherto. The front passenger compartment was, accordingly 0.5in (12mm) higher at 35.5in (901mm) while there was a 33in (838mm) clearance at the back which permitted two children to be carried. The doors were also lengthened, by 8.5in (215mm), to 3ft 5in (1.04m), and Jaguar took the opportunity to introduce ‘burst proof’ locks. The model was instantly identifiable by a length of brightwork introduced along the sides of the doors.

Mechanical Modifications

The springs and dampers were uprated to cope with the extra weight. Under the bonnet the alternator was fitted with a shield to protect it from heat generated via the header tank and the exhaust manifold. At the same time there was improved protection introduced between the exhaust pipe and the lowered floor.

The opportunity was also taken to offer automatic transmission to the E-type range. Specified with the American market very much in mind, a Borg-Warner Model 8 gearbox was employed with D1 or D2 option. The former position provided the driver with kick-down changes into low or intermediate positions, instead of only the latter when D2 was selected. On the home market this meant that the final drive ratio was changed from 3.07:1 of the manual cars to 2.88:1. However, on the American market where top speed played second fiddle to off-the-mark acceleration, a final drive ratio of 3.54:1 was employed.

Cosmetic Modifications

In addition to the seating improvements, other changes included a deep glove compartment, with lockable lid, and a full width parcel shelf below. Instrument lighting was improved and was green-tinted. Heating and de-misting, always a Jaguar weak point, were also changed with variable direction outlet nozzles, as fitted to the contemporary Mark H-derived S-type saloon.

Reactions

So did this extra weight unduly affect the 2 + 2’s performance? In its issue of 15 June 1966, Autocar, as it had been since 1962, reported on a road test of a 2 + 2 and commented on how little the car’s increased weight had affected the E-type’s performance:

As far as the improved seating was concerned – ‘two children … tumbled in without a thought’ – it was also found that an adult could also be accommodated, provided that he sat sideways. The car in question achieved a top speed of 139mph (224kph).

The arrival of the 2 + 2 helped to push E-type production to record levels in 1966 with 6,880 cars built, the new variant proving the most popular option, with 2,627 produced, as opposed to 1,904 conventional coupes and 2,349 open two-seaters. However, overall output fell back badly in 1967 with 4,989 Es built. Exactly 2,500 were open cars, with production of the closed models almost evenly split between the coupe (1,205) and the 2 + 2 (1,284).

CORPORATE AFFAIRS

Before continuing to chronicle the car’s evolution in detail, it is first necessary for us to take a brief look at the changes in Jaguar’s corporate status which were taking place at this time. As will already have been apparent, the firm had been built up around Lyons, who was sixty-five in 1966, while many members of his small, hand-picked team of directors were also approaching retiring age. Tragically, his only son John had been killed in France, just prior to the 1955 Le Mans race, when his works Mark VII saloon was involved in a head-on crash with an American army lorry, leaving Lyons without a male heir.

During the 1960s Jaguar had also grown by acquisition. In addition to its purchase of Daimler, Jaguar bought truck manufacturer Guy Motors of Wolverhampton in 1961 and two years later, in 1963, the local Coventry Climax company, which manufactured fire pumps and fork lift trucks. The same year there were talks with Lotus about some sort of alliance and, in April 1963, Lyons reported to his board of his discussions with Colin Chapman. The negotiations dragged on and, in December, Sir William said it would not go ahead because of Lotus’ ‘… rejection of our proposals to which they had previously agreed’. But in the same month Jaguar bought proprietory engine manufacturer Henry Meadows, Guy Motors’ next door neighbour.

Meanwhile there had been dialogues with commercial vehicle manufacturers Leyland Motors, which had bought the Standard-Triumph car company in 1961, about a possible get-together. Lyons and Leyland’s chairman, Sir Henry Spurrier, were old friends and John Lyons had been a Leyland apprentice. But any thoughts of a liaison in the early 1960s came to nothing because the talks could only have resulted in a take-over of Jaguar and Sir William fiercely guarded his company’s independence.

But in 1965 Jaguar’s hand was, to some extent, forced when the British Motor Corporation (BMC) purchased Pressed Steel, which manufactured bodywork for the Mark X, Mark II and S-type saloons and, incidentally, the fixed-head E-type’s roof section. This meant that Jaguar’s body supplier was owned by a rival and the purchase led to overtures to Lyons by BMC’s chairman Sir George Harriman.

In the mid-1960s the Corporation was riding high on a wave of technological success in the shape of its top-selling Austin and Morris front-wheel drive Minis and 1100s, but underpricing, and a lack of forward planning, had seen a steady erosion of corporate profits. Therefore a match with Jaguar made sense because there was very little overlap in the respective companies’ products and the Coventry firm had always been profitable. Lyons and Harriman met in private and the merger was announced in July 1966. The resulting firm was known as British Motor Holding (BMH) and the agreement was such that Lyons could continue running Jaguar, just as he had been doing, and with no interference from BMC’s Longbridge headquarters.

E-TYPE JAGUAR, BRITISH SALES, 1965*–1975

| 1965 |

1,327 |

| 1966 |

1,379 |

| 1967 |

1,093 |

| 1968 |

882 |

| 1969 |

991 |

| 1970 |

1,377 |

| 1971 |

791 |

| 1972 |

875 |

| 1973 |

1,337 |

| 1974 |

442 |

| 1975 |

173† |

| Total |

10,667 |

| |

|

* 1961–1964 not available

† Includes XJ-S |

In 1967 Jaguar made a post-tax profit of £1.1 million but, overall, BMH made a loss of £3.28 million, which paved the way, with governmental encouragement, for its effective take-over by the Leyland Motor Corporation, the latter having by this time added Rover to its corporate orbit. The resulting British Leyland Motor Corporation officially came into existence in May 1968 and, in October of the same year, Jaguar announced its superlative XJ6 saloon, which replaced the Mark II and S-type and the Mark X’s 420 derivative. Not only was the XJ6 Sir William Lyons’ favourite car but it was also destined to endure for an astonishing eighteen years and carry the Jaguar company over what was destined to be the most traumatic era in its history.

US EMISSIONS LEGISLATION

In 1968 the firm was also having to grapple with the effects of new American safety and emissions legislation which had come into force in the beginning of the year. As will already have been apparent, Jaguar in general and the E-type in particular were deeply dependent on transatlantic sales. Therefore when emissions legislation began to apply to American cars from 1963 onwards, it could only be a matter of time before imported cars would have to adapt to increasingly stringent laws. Such modifications first appeared on the E-type from December 1967, the model being subsequently, and unofficially, known as the ‘Series I½’.

This legislation, which was to affect every new car sold in America, emanated from the West coast city of Los Angeles. There for many years smog was considered to be little more than a geographical problem. But in 1950, Dr Arlie Haagen-Smit, a respected Californian biochemist, established a link between smog and motor car emissions. Hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide were causing the trouble and, in 1961, all Californian cars had to be fitted with a system which contained crankcase emissions within the engine, feeding them back through the carburetter. This was extended to all American cars from 1963 onwards. These developments, as well as structural requirements to improve a car’s behaviour under crash conditions, were highlighted in 1965 by the publication in America of Ralph Nader’s best-selling book, Unsafe at Any Speed, which reflected the growing public awareness of the subject.

This culminated in the passing of the Motor Vehicle and Road Traffic Act of 1966. The new legislation not only related to American-built cars but also to imported ones, the manufacturers of which were also going to have to modify their products as from 1 September 1967. However, some ambiguity in drafting the regulations resulted in the foreign car makers taking the administration to court and some typically robust oratory on behalf of the British manufacturers by MG’s deputy chief engineer, Roy Brocklehurst, produced a four-month stay of execution, the new ruling only becoming effective from 1 January 1968.

Externally at least the ‘Series IW E-type, which applied to all versions, did not begin to reflect the £250,000 which the firm had spent on the modifications demanded by the new regulations. Perhaps the obvious difference was that by moving the headlamps forward by 2.5in (63mm), the protective Triplex plastic covers were dispensed with. However, the original slim bumpers, air intake and small sidelights were retained. The hitherto eared hub-caps were replaced by earless ones and cross ply tyres took the place of radial ones. An exterior mirror was added to the driver’s door.

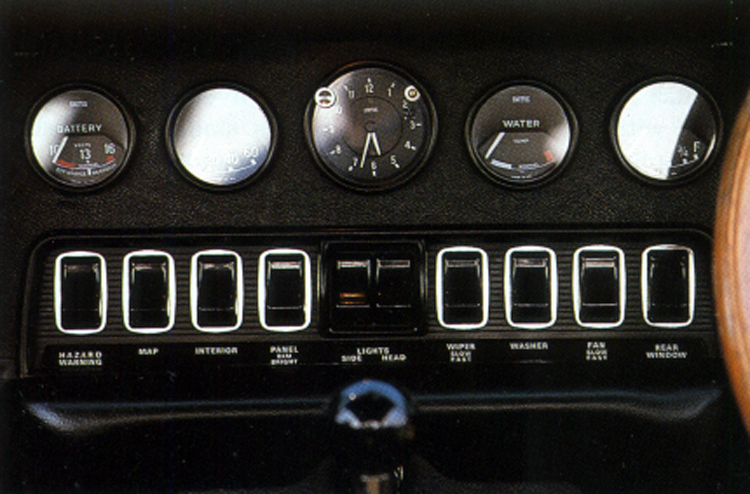

These were relatively modest and straightforward changes but more radical modifications were made inside the car. In the driving compartment, the elimination of reflective surfaces was a prime candidate for change though, it should be noted, these and other interior modifications were only applied at this stage to left-hand drive cars; right-hand ones continued much as before. The facia was accordingly completely redesigned. Switches were now of the non-projecting rocker type. There was the addition of a hazard warning light switch. A protective strip was introduced below the switch bank while the windscreen wiper motor was replaced by a unit which would cut out rather than burn out in the event of the blades being immobilised by ice or snow. The heater controls were also changed. Out went the sliding control, with projecting levers replaced by flat-headed ones with pull-push action. There were revised demisting slots.

Some changes had nothing to do with the new regulations – such as the fitment of a transistorised electric clock and battery conditions indicator – but a relocated, redesigned cigar lighter was, and there was a new combined starter and ignition switch which replaced the dated, though distinctive, separate units. New seats with adjustable squabs were fitted, which employed a positive locking lever. A new safety harness was standardised. The regulations even specified a new type of rear-view mirror with plastic surround, arm and fixing screw designed to break or collapse under a 901b (40.8kg) force. All these changes were undertaken with relatively little difficulty but when it came to introducing new door locks, more radical surgery was required to the doors and their adjoining rear panels. The American regulations demanded that the locks be of the ‘burst proof type and would not fly open in the event of an accident. Introducing this new type of lock required that the door be completely redesigned, while its interior handles were also recessed to prevent them being inadvertently opened. New, more rounded window-winders were also introduced. The E-type’s steering gear was already capable of not deflecting by more than the required 5in (127mm) in the event of a 30mph (28kph) crash but a General Motors’ Saginaw energy-absorbing steering-column was incorporated.

A considerable amount of time and effort was spent in modifying the XK engine to meet the stringent anti-smog regulations. Jaguar experimented with no less than three systems. Originally it was thought that the answer might be petrol injection, which had been race-proven on the D-type, and a Mark VII saloon was accordingly modified. However, these experiments showed that the system was not particularly efficient where it was most needed: and that was on tick-over (in other words in a traffic queue).

Undoubtedly the problem could have been resolved but, along with other manufacturers, Jaguar was working against the clock and then looked at an arrangement that the Americans themselves had pioneered: air intake into the exhaust. With this layout, air was injected, via nozzles from an engine-driven pump, to the exit side of the exhaust valves. Introducing what was, in effect, extra oxygen meant that any partially burnt gases were sufficiently oxidised for the combustion process to be completed.

This sounds straightforward enough but problems could occur when the throttle was suddenly closed. The mixture could become temporarily over-rich so instead of igniting in the combustion chambers it would do so in the exhaust manifold, which produced an annoying though harmless explosion which, at its worst, could split the car’s silencer. To cope with that particular contingency, a gulp valve was introduced into the system, which injected a calibrated quantity of air into the inlet manifold, triggered by a sudden rise in manifold depression. This ensured that combustion was completed in the cylinder. The problem with this arrangement was that it subjected the exhaust sytem to additional heat, which would then be conveyed to the body – to the ultimate detriment of its occupants. Consequently a more expensive exhaust system would be necessary to ensure a normal working life.

Eventually Jaguar opted for the Zenith Duplex system. This provided two paths for incoming gases, controlled by a pair of throttles. The principle was that, at low speed, the main inlet passage was blocked off, the mixture being deflected via an exhaust heated hot spot which ensured the complete evaporation of any remaining fuel globules. The incoming mixture thus became a complete gas and burnt without any residue. The system only applied to low throttle openings where a clean exhaust was most difficult to attain. The main and secondary throttle did not begin its work until its by-pass counterpart had met the idling and light cruising requirements.

These exhaust emissions were subjected to stringent carbon monoxide and hydrocarbon levels. The cars were given a rigorous cycle of testing, starting with idling and progressing to slow speed cruising, acceleration to be followed by deceleration. These were carried out during a 50,000 miles (80,465km) rolling road test, with checks made at 4,000 miles (6,437km) intervals. One tune-up was permitted during the test span with two permissible on non-Jaguar cars of under 220cu in (3,605cc). The XK engine was a relatively efficient unit but the original triple SU carburetter layout was dispensed with and replaced by a twin Zenith-Stromberg CD carburetters and a new inlet manifold. In addition, the ignition timing was revised, to a static setting of 5 degrees before top dead centre. The centrifugal advance mechanism was also modified and the vacuum mechanism dispensed with.

These changes resulted in the requirements being met, and petrol consumption actually improved by a modest five per cent. Conversely there was some falling-off in top end power. Jaguar claimed seven per cent above 4,000rpm and on ‘federal’ engines; this meant 171 instead of 265bhp.

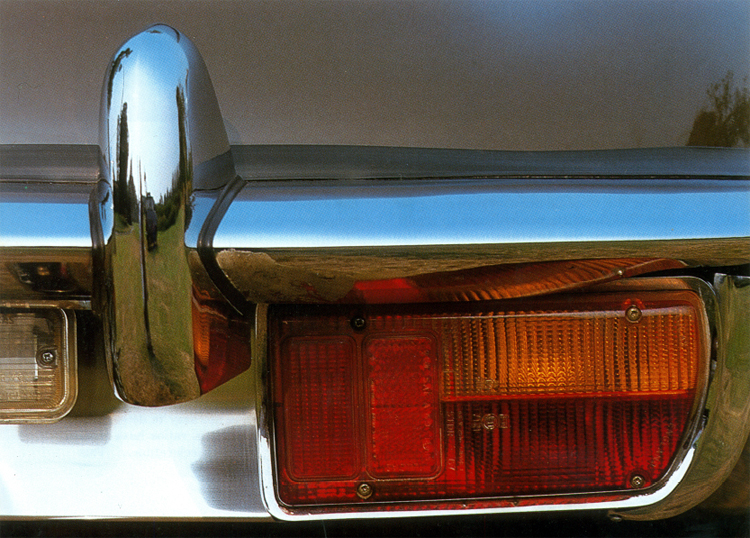

Further modifications to the E-type became apparent when Jaguar unveiled its Series II car at the 1968 London Motor Show. Externally the changed headlamp layout was perpetuated though more significantly, the air intake duct at the front of the car was enlarged, by no less than sixty-eight per cent. This greatly improved airflow and was demanded by the fitment of a new air conditioning system which was to be offered as an option on the American specification Series II. Jaguar also took the opportunity to improve engine cooling – never a strong point – by adopting a crossflow radiator, and the single engine driven cooling fan was replaced by twin electric units.

In addition, the original thin delicate bumpers were replaced by thicker wraparound ones. The side light flasher units were relocated below the front bumpers while flasher repeaters were introduced at both ends of the car. At the rear, the enlarged bumpers were perpetuated and new rear lights were moved from above the bumpers to below them. These were also bigger and angular while the reversing lights were rather awkwardly located either side of the new square type American number plate mounting.

On the mechanical front, the E-type’s braking system came in for its first ever major revision. The original Lockheed discs were replaced by Girling units with three cylinder calipers, which increased the rubbed area. For the first time the E-type was offerred with the option of power steering, a Pow-a-rak system by Adwest Engineering, while chromium-plated disc wheels were available as an alternative to the customary wire spoked ones. The right-hand drive cars received the new American style interior, complete with new dashboard.

Otherwise the cars were unchanged, with the exception of the 2 + 2 E-types, which had revised windscreens. The angle was increased from 46.5 to 53.5 degrees with the result that its lower edge was brought further over the scuttle.

In 1969, the first year of the Series II E-type, production ran at record levels. A total of 9,948 cars left Browns Lane: 4,287 roadsters, 2,397 coupes and 3,264 2 + 2s were built. Output would never again reach such heights.

Production dipped to 6,686 cars in 1970 and to 3,781 in the following year. But by that time the Series III E-type had appeared with a new 5.3-litre V12 engine. Before examining the origins and development of this impressive power unit, it is first necessary to take a look at the E-type’s career on the racing circuits of Britain and the world.