The 2 + 2 tends to be the Cinderella of the E-type range, despite its practicality and popularity when new. This is probably because of some dilution of the coupe’s lines and a modest falling-off in performance. One to watch perhaps?

‘Blessed is he that expects nothing, especially where second hand motors are concerned.’

Max Pemberton in The Amateur Motorist, 1907

It will be apparent that it was the twin appeals of performance and magnificent lines that sold the E-type when it was new. Although still a respectable performer, the E’s looks can still turn heads but they can also be a trap for the unwary! The purpose of this chapter is to weigh up the pros and cons of the various models. Then when you have to decide which is the car for you, how you go about evaluating a good example, first by examining it and then, if it is drivable, taking it on the road.

But first it is probably appropriate to remind ourselves of the various models in the E-type range, all of which, apart from the 2 + 2 coupe, are available in roadster and fixed head coupe forms.

| 1961–1964 | 3.8-litre (Series I) |

| 1964–1968 | 4.2-litre (Series I) |

| 1966–1968 | 4.2-litre 2 + 2 coupe (Series I) |

| 1968–1971 | 4.2-litre (Series II) |

| 1968–1971 | 4.2-litre 2 + 2 coupe (Series II) |

| 1971–1973 | 5.3-litre V12 2 + 2 coupe (Series III) |

| 1971–1975 | 5.3-litre roadster V12 (Series III) |

So of all these cars, which are the most sought after models? I will refrain from quoting prices because they will become outdated between my writing these words and the book appearing, such is the volatility of the classic car market. However, some trends for the E-type are already discernible. One is that, like most older cars, the convertible body tends to fetch rather more than the closed version. At the time of writing, summer 1989, the open 3.8-litre car is at about level pegging with its V12 equivalent though the latter looks all set to overtake it and will probably become the E-type to own in the next decade. Next come their respective closed versions. Then there is the Series I 4.2-litre roadsters of 1964–1968, followed by the V12 fixed-head coupe, and the Series II roadster, then the fixed-head coupes, starting with the 1961–1964 3.8-litre. Cinderella of the range is, ironically, the most practical and popular E-type of its day and that is the Series I and II 4.2-litre 2 + 2s which, of course, are only available in fixed-head forms.

So let’s take a closer look at the respective advantages and disadvantages of the various models.

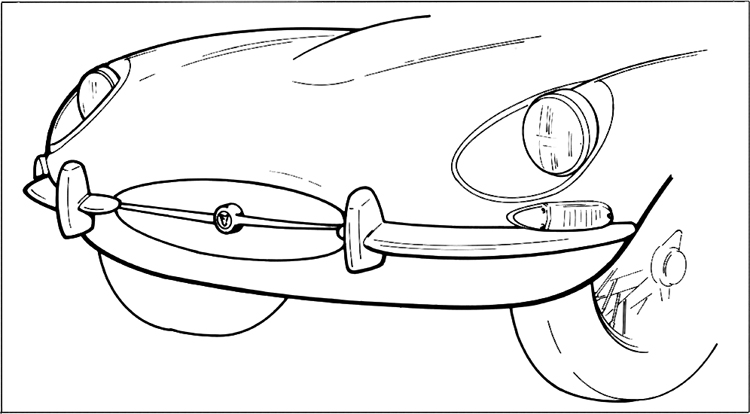

There is little doubt, from a visual standpoint, that both this and its pre-1967 Series I successor, were visually the most impressive of the E-type model line-up. They are easily identifiable by their thin, tapering front and rear bumpers, modestly sized frontal air intake and headlamps contained behind perspex covers.

As far as the interior of the 3.8-litre cars is concerned, they have the handsome aluminium-finished central dashboard with black-faced instruments, which are particularly easy to read, while the centrally-positioned head and side light switch, a feature of all Jaguars of the day, has a distinctly pre-war feel to it if you like that sort of thing! Similarly there is a separate ignition key and starter button, a feature which harks back to the firm’s pre-war days. An original Radiomobile radio, which was set in the central console, below the ashtray is an obviously desirable extra. The aluminium was perpetuated on the transmission tunnel though was subsequently changed to a black vinyl finish.

This brings us back to the seats. The leather-trimmed buckets came in for plenty of contemporary criticism as being uncomfortable though don’t forget that the steering column is adjustable for reach by a knurled nut and rake is courtesy of a moveable slide and lock nut located alongside the column. There is also that identifiably ‘Jaguar’ wood-rimmed steering-wheel.

All these features relate to the roadster and fixed head coupe though each have their respective advantages and disadvantages. Probably none of us need converting to the joys of open air motoring – providing the weather is fine. The E-type’s mohair hood, which was made by Jaguar in its trim shop, is reasonably easy to erect and keeps the weather out, to some extent! A popular fitment for the roadster was a glass fibre hard-top, available from March 1962, which is secured to the top of the windscreen by three over centre catches and makes for a snug interior. The problem is that it immediately underlines the car’s limited demisting arrangements, never a Jaguar strong point, a shortcoming which was not rectified, and then not truly satisfactorily, until the V12 acquired a rudimentary system in 1972. Don’t expect to get too much luggage in the roadster’s shallow boot. Beneath the floor is the spare wheel, and alongside it, the kidney-shaped petrol tank.

The 2 + 2 tends to be the Cinderella of the E-type range, despite its practicality and popularity when new. This is probably because of some dilution of the coupe’s lines and a modest falling-off in performance. One to watch perhaps?

Even the most ardent E-type enthusiast would concede that the roadster’s hood may leave something to be desired. The glass fibre hard-top, shown on this 1964 car, is a desirable optional extra. But in colder weather, de-misting can become something of a problem.

The fixed-head coupe, by contrast, is a far more practical car for round the year motoring and, I must confess, that I personally find its lines superior to those of the open car. Luggage accomodation is obviously superior with a 4ft (1.22m) long and 3ft (0.91m) wide storage space, plus the convenience of a rear opening door.

So much for the 3.8’s visual pros and cons but what about its mechanical peccadillos? As mentioned earlier in the book, its top speed is more likely to be approaching the 140mph (225kph) mark, with the aerodynamically superior coupe having the edge on the open car, rather than the 150mph (241kph) attained by the 1961 road test cars. The 3.8’s 4.2-litre successor should record about the same top speed though with improved acceleration. The real limitation of the 3.8-litre cars is their Moss gearbox which was also adversely commented upon when the E-type was new, so you can imagine what it’s going to be like twenty or so years on! By this time synchromesh will probably be poor and the box does not lend itself to fast gear changes while first and reverse gears may be excessively noisy. So this is a drawback on the 3.8 – if you intend to do a lot of driving. Another shortcoming, which will only become apparent if the car is used a lot at night, is its relatively poor headlights with beams diluted by diffusion and scatter. The Series I 4.2s, which were fitted with sealed beam units, are superior in this respect while the Series II cars, with their aesthetically instrusive lamps, are even better. Series I and II cars also benefited from the fitment of an alternator to replace the long suffering dynamo, which never really seemed to be up to the job. Early E-types also have a tendency to overheat in heavy traffic, which is particularly noticeable in the coupe. You have been warned!

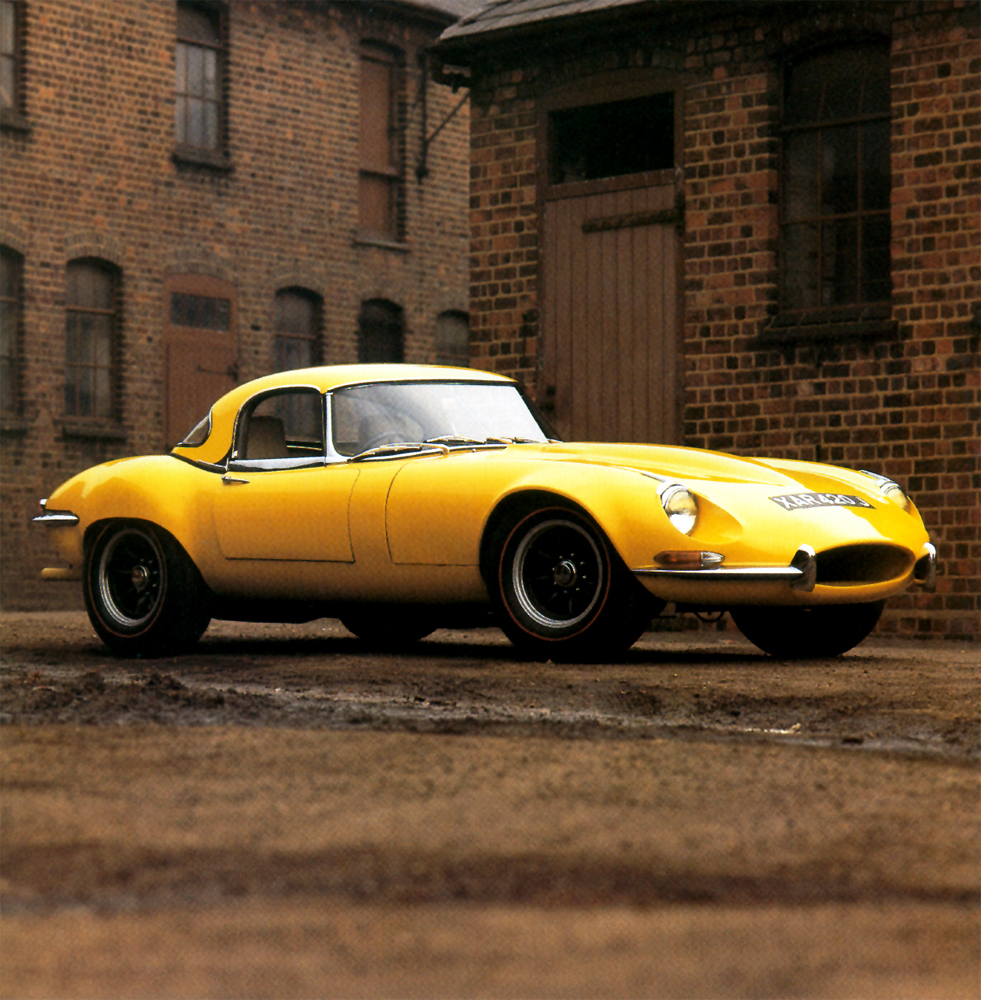

As with most collectable cars, the E-type tends to be more sought-after in roadster than in coupe form. This is a 1962 car and therefore a 3.8-litre model.

Yet another shortcoming that will only become apparent on a test drive, is the relative inefficiency, certainly by present day standards, of the Dunlop bellows type servo and its attendant discs. The 4.2-litre cars were fitted with the greatly improved Lockheed in-line unit and thicker discs. Some 3.8s have been converted to the later servo in view of the fact that spares are extremely difficult to find for the Dunlop original.

The same also goes for the original Lucas immersed centrifugal impeller petrol pump, which has often been converted to the more conventional external unit, similar to that employed on the 4.2. This followed the factory issuing a conversion kit for the 3.8 in the early 1970s for the fitment of an SU type AUF 301 diaphragm pump. It was located on the right-hand side of the spare wheel well, alongside the wheelarch.

However, on the debit side, a neglected open example will probably require more radical restoration, because it is more vulnerable to the elements than a closed one.

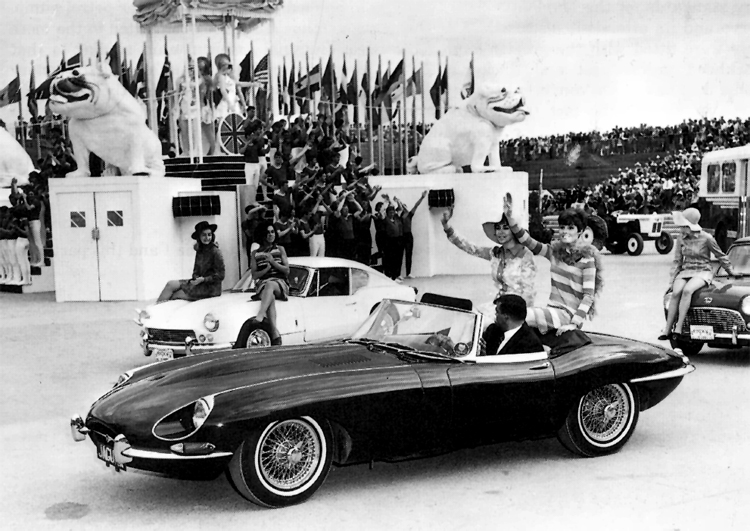

A 1967 ‘Series I½’ perhaps offers the best of both worlds in that it retains the attractive visual attributes of the Series I and the exposed and improved headlamps of the Series II. This is an America-sourced roadster pictured at the Montreal-based Expo 67.

This was externally very similar to the 3.8 so the same remarks therefore apply. The big changes were inside the car. There is no doubt that the new seats, which replaced the original bucket ones, were a great improvement on their predecessors. They are finished in pleated leather, are wider and more deeply upholstered, can be tilted forward, which allows easier access to the rear of the car, and are also adjustable for rake. Although the dashboard layout remained unchanged, the aluminium dash panel did produce some undesirable reflection and was replaced by a black finished panel though the instruments do not stand out quite so well. As already mentioned, acceleration is a noticeable improvement on that of the 3.8, and interestingly petrol consumption is slightly better. But the greatest improvement relates to the all-synchromesh gearbox, which was fitted right across the Jaguar range for the 1965 season. The advantages of the improved headlights have already been mentioned, so perhaps in many respects, the Series I 4.2 combines looks, performance and comfort, unless you happen to be the right shape for the 3.8!

It is ironic that the family man’s E-type fetches the least money of any car in the range though undoubtedly its rather high lines make it visually inferior to the equivalent fixed-head coupe. On the plus side, as it were, is obviously the rear seat though it is only really suitable for carrying children over long distances. Conversely there is increased weight, fuel consumption and a slightly clipped top speed. Also remember that automatic transmission, a Borg-Warner Model 8 three-speed gearbox, was introduced with this model, which flew in the face of the sports car concept, with once again a dilution of both performance and fuel consumption. We should not overlook the so-called Series I½ of 1968, which features the usual 4.2-litre exterior, with the exception of the improved, open, forward-mounted headlights.

These are immediately identifiable by their enlarged air intake, with thickened-up bar containing the Jaguar badge, and exposed headlights. The small sidelight/flasher units were replaced by larger forward-mounted units located below the bumpers. At the rear, ugly rectangular casings located below the back bumper took the place of the earlier neat rear light/flashers. There were also new spoked wheels with a forged centre hub and straight spokes. Radial tyres were fitted as standard.

The interior benefited from the new safety conscious tumbler switches, and a combined steering-column lock and ignition key although, it has to be said, these combine to produce some dilution of personality.

Under the bonnet, you can easily identify these Series II cars by their matt black cam boxes, with aluminium fluting, while the twin electric fans are another recognition point. Incidentally, if you’re faced with the prospect of an export left-hand drive version of the E-type, remember that it may be fitted with air conditioning, a facility that was not available on the right-hand drive cars because the unit was obstructed by the steering-column. So it cannot be converted back to right-hand drive, not a particularly difficult job but you’ve then got a non-original car, without sacrificing this facility. Performance of the Series II was slightly inferior to that of the I and this particularly applies to the American specification cars, the top speed of which was effectively strangled by its de-toxing equipment. You cannot expect much more than 120mph (193kph) from such a Series II.

Compared with the pre-1971 E-type, the V12 Series III generation of 1971–1975 is visually different, particularly if an example is placed alongside a six. There are many who prefer the proportions of the pre-1971 E-type though no doubt there are plenty of V12 enthusiasts to challenge this viewpoint! Apart from having the wheelbase of the 2 + 2, it also has a wider track. The enlarged front air intake is a distinctive feature with, for the first time, a chromed grille and an additional air duct below. It was also goodbye to the handsome spoked centrelock wheels, mourned by many, and replaced by the chromed disc ones with fatter profiles and extended wheelarches. However, you should remember that wires were available at extra cost, so if you’re contemplating a V12 with spoked wheels, this is perfectly in order.

Obviously under the bonnet, you won’t be in any doubt that you’re greeted by twelve cylinders. As far as top speed is concerned, this is about the same as the 4.2 at around 140mph (225kph). But you’ll soon feel the benefit of the improved acceleration; that magnificent turbine-like performance which is unique to V12 power. On the debit side, they’ll be high fuel consumption, about 14mpg or less, with the popular automatic version being even thirstier. The HE version of the V12 was still some years away. Also remember that ultimately you face a big engine repair bill if the car has done a high mileage. Fortunately the V12 is a strong, reliable unit and will cover at least 100,000 miles (160,000km) before it needs overhaul but when the time comes, be prepared for a big bill. This is not because the power unit is excessively complicated. It isn’t. It’s just that there’s about two of everything to replace or recondition!

The 3.8-litre coupe is probably marginally faster than the open car in view of its better aerodynamics, not that you’d be able to prove it in Britain though!

The coupe has the advantage of extra carrying capacity over the roadster, plus impressive looks, as this 1964 car shows.

A magnificent 1971 Series II coupe. This Series of the 1968–1971 era tends to be slightly cheaper than its Series I predecessors though the margin is a narrow one.

Once again the E-type coupe, of whatever year, scores as far as carrying capacity is concerned.

You’ll also have the benefit of power steering as a standard fitment on the Series III though some drivers complain that it is too light and lacks the assurance of road responses through the smaller leather, rather than big wood-rimmed wheel. The post-1972 cars have an additional appeal because of their improved fresh air facility and if you opt for a roadster with a hard-top, it is fitted with its own air outlet, which went some way to curing the model’s ongoing demisting problems.

A 1968 left-hand drive Series II coupe. Note the repeater flashers on the sides of the front and rear wings, earless hubcaps and driver’s wing mirror.

A fixed-head coupe Series III underlines the practicality of the V12-powered coupe in bad weather, as this example, pictured on a rainy day in the highlands of Scotland, demonstrates.

So far so good but now we come to the potentially tricky business of evaluating the worth of a particular example. But before looking at the specific areas to check, I cannot overstate the point that the total restoration of an E-type is not a proposition for the amateur. This is mainly because of its sophisticated and unique body construction with its central tub and triangulated front section. One of the main difficulties is that, in the process of replacing the rusted parts, the originals have to be removed which will then weaken the monocoque and, more significantly, the hull may move slightly out of true. For a thorough structural re-build, the shell has to be mounted in a special jig to keep it in alignment. Also remember that some of the individual body panels were concealed by leading, so you’ll see the importance of recognising your own limitations.

From the mechanical standpoint, although the overhaul of the six-cylinder XK engine is probably within the capabilities of the competent amateur, the same cannot be said for its independent rear-suspension. But on balance, you should be on the lookout for a car with a good body/frame and regard the mechanicals as secondary. Nowadays, it’s almost impossible to find an E-type that hasn’t rusted to some extent, so be on your guard! Yet another problem is that an E-type with a bad case of tin worm can be smartened up to look perfectly respectable. If you don’t want to get caught, read on…

As the condition of the E’s bodywork is your prime consideration, make this your first port of call. Beginning at the front of the car, carefully examine that magnificent but vulnerable front bonnet and wing assembly. Start by gently tapping it around the front end. A deep resonance will indicate the presence of filler and you can confirm this by opening it and checking for dents. You may disturb some rust in the lower front nose section which may indicate the advanced decomposition of the panel underneath. Another vulnerable point is on the top of the wings, alongside the chrome strips which mask the joints between them and the centre section of the bonnet. Have a look at the underside of these joints while you’ve got the bonnet open. If there is rust topsides, the chances are that it will be even worse underneath with the flanges having rusted away. After you’ve taken a close look at the bonnet, stand back and see how well it appears to blend in with the rest of the car. If the alignment is poor, it might be an indicator of some long forgotten accident though it could have been badly refitted after its removal for a more innocent reason. The bonnet is adjustable in practically every plane with the hinges shimmed to provide a precise join. Incidentally, replacing a bonnet after it has been removed is a job that could even take a professional restorer a couple of days to complete.

Usually, cars that have been extensively modifed tend to be worth less than their perfectly standard contemporaries. Richard Essame’s Chevrolet V8-powered E-type of 1971 shows a particularly high standard of conversion work, so this car would have some value in its own right.

The 1967–1968 ‘Series I½’ E-type, which retained the Series I bumpers, and air intake but featured the exposed headlamps of the Series II.

The Series II cars, made between 1968 and 1971, with full-width bumpers, enlarged air intake and bigger sidelight/flasher units relocated beneath the bumper.

The Series III models of 1971–1975 are easily distinguished by their chromium-plated grille, with air intake below.

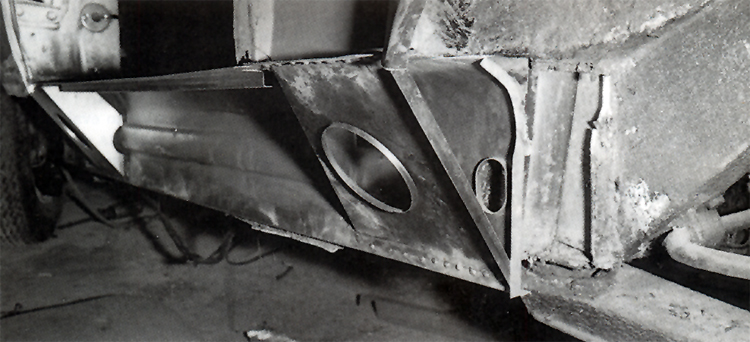

Moving back to the main central tub, you should carefully examine the sills. The originals were spot-welded in position but, if they have been replaced at some time in the car’s life, they will be continuously welded or brazed. Their condition is a good indicator of the general condition of the car’s hull. This particularly applies to the roadster, which hasn’t the additional roof reinforcement provided by the coupe. The open car will flex badly if the sills are rusted or badly holed.

At the rear of the car, check the edges of the rear wings and also underneath the car in the triangular area below the bumper and behind the wheel. The open car doesn’t have an inner wing, so the apex of the wing proper is a favourite rust point. They do exist, however, on the coupe so closely examine the interior of the wings and around their edges for indications of corrosion.

The hollow section sills lacked proper drainage or rust protection and quickly perforated at the bottom. Before buying, the area where the sill meets the floor under the car should be checked.

Almost invariably the sills will need replacing; here the outer ones on a 2 + 2 E-type have been removed and the rust damage to the floor/inner sill and the flitch plate adjacent to the rear wheel is very evident.

A similar area to that in the above picture is being restored on another car: note the new flitch plate and inner sill.

At this point, have a look underneath the car and, with the aid of a powerful torch, examine the condition of the three strengthening ribs you’ll see there. Check the nearby points where the rear-suspension radius arms are joined to the rear floor. This is a stress point and look out for rusting or for evidence of a botched repair. Either shortcoming is potentially dangerous. Also check the state of the hollow transverse beam you’ll find beneath the seats.

Next open the boot, lift the Hardura matting if it is still present, and remove the spare wheel. Have a look at the well and also the point where the inner wing joins the floor. Another vulnerable area is around the rear number plate and the bodywork immediately above the twin exhaust pipes.

The doors too are not immune from corrosion. The danger area is where the outer skin joins its inner counterpart. In order to see whether rust has got a hold, grasp the lower edge of the door with your thumb on the outside of the door and try to flex the metal. If it produces a muted cracking noise, you’ll know that all is far from well below the surface.

Now turn your attention to the car’s mechanical aspects. Return to the front of the E-type, open the bonnet and carefully inspect the front framework for signs of rust or accident damage. Check for cracking in the vicinity of the joints. The frame itself isn’t particularly prone to corrosion because of the presence of engine oil and vapour though it can suffer from spilled battery acid, particularly if its tray has disintegrated at some time. Therefore examine the frame in its immediate vicinity. Make a point of checking the bulkhead for evidence of denting, indicating signs of a bad crash, at the point where the frame is bolted to it. Also remember that you’ll find the 3.8 and 4.2 cars’ chassis plate on the front cross member above the damper mounting. If there isn’t one, this might indicate that a new subframe has been fitted, perhaps the legacy of some long forgotten front end shunt. The Series III plate, by contrast, is to be found on the body of the car, under the bonnet, adjoining the bulkhead.

The first thing is to check that the E-type you are inspecting has its correct engine. It is not unknown for an earlier XK one, or a similar unit from the contemporary Mark X saloon, to have been fitted. Occasionally a 3.4-litre engine, with its less desirable pre-straightport head, might have been substituted and, the other day, I even heard of an XJ6-powered E-type! You’ll find the engine number on the right-hand side of the block above the oil filter and also on the front of the cylinder head. They should correspond and, if they don’t, it indicates that a replacement head has been fitted at some time. If the numbers do tally, they should also be the same as that shown on the data plate that you’ll find on the sill on the off side of the engine compartment.

You’ll only really be able to evaluate the condition of the car, and its engine, by driving it but don’t be too alarmed if you’re contemplating a 3.8 which looks as though it is suffering from an oil leak. Many do! The front-suspension is, by contrast, virtually trouble-free with wear often confined to the top and bottom ball joints. Alas, the same cannot be said for the rear-suspension, though this test is best reserved for when you drive the car, but some elements can be evaluated when the vehicle is stationary.

Worn splines are yet another potential hazard. If you are able to, loosen off the wheel nuts of both rear wheels. Then put the car in gear and apply the handbrake. Now jack the car up and place your hands at the nine and three o’clock positions. Move them within a limited arc. Any discernible movement will indicate that the splines are worn. You should also check the front wheels in a similar way though they don’t normally suffer as much. You can also visually inspect the splines by removing the wheel in question completely. The splines should be flat on top, not pointed, which indicates undesirable wear.

Inner and outer wings meet at the rear to form a moisture trap, and very often this much of the rear wing has to be replaced.

But to revert to the rear end. A leaking differential is a fairly common E-type failing. This is usually caused by the inboard disc brakes overheating, which is conveyed to the differential, damaging the oil seals in the process. As the drive shafts do double duty as the top suspension link, this also puts additional stress on the long-suffering seals. As a result, lubricant gets on to the inside faces of the discs, to the ultimate detriment of the brakes. Yet another contributory factor is the pressure which can also build up in the differential assembly because of a blocked breather.

If the seals have failed, then you’re faced with the problem of dismantling the entire-rear-suspension system which, although not particularly complicated, is not a job for the first-former. The diff unit itself is attached to the body by large Metalastik mountings. To check that these all-important components haven’t separated, jack the car up and place it on axle stands positioned on the two longitudinal body members. Position the jack under the differential. Then lower the jack slightly. The differential should remain in position. if it moves appreciably, then you’re in trouble. Don’t worry, it can’t fall out as it’s held in place by the propellor shaft and anti-roll bar. Other wear points are the bottom pivot bearings on the rear stub axle carriers, the inner needle roller bearings on the inboard end of the wishbones and the anti-roll bar mountings and bushes.

An E-type’s floor, and the bulkheads at either end, are all prone to rot. The bulkheads can usually be repaired but the floor is normally best replaced.

It is also worth checking the steering, evaluating it in a stationary position. The rack and pinion layout isn’t particularly prone to wear and if there is some slack in the steering it might be the result of wear in the two universal joints in the steering-column. It could also be the result of worn rack mounting bushes.

While you’re looking inside the car, check under the carpets to see whether some ‘butcher’ has carved the floor around the transmission tunnel to detach the gearbox from the engine. This is because an E-type clutch only has a life of about 30,000 miles (48,279km) and the engine/gearbox unit has to be removed to replace it. Such surgery means that the engine could remain in situ, so be on the lookout for it.

The area around the rear number-plate panel is another place subject to corrosion; here a new section is being let-in beneath a fixed-head’s rear hatch opening.

After repairs have been completed, the seams need to be lead-filled and filed, just as they were at the factory.

Make a point of closely examining the condition of the car’s interior. The leather seats, in particular, can be expensive to have renovated and repaired. Also if the car you are contemplating has been neglected, then the inside of a coupe will inevitably be in better condition than a roadster, which is more vulnerable to exposure to the elements.

Now for the drive itself. The XK engine should start readily enough and quieten down within a minute or two. However, some tappet noise is not undesirable. Once the engine has reached its operating temperature, check the oil pressure gauge. 40psi at 3,000rpm is an acceptable figure and be particularly suspicious of any reading below 30. The clutch has a fairly long travel and will only begin to take up rather late in the day. Don’t get caught unawares by the high first gear, so you might experience some difficulty in getting a smooth take-off. You’ll also find that first is noisy on the 3.8-litre. This is quite normal but be more suspicious of grating or grinding. Gearbox repairs can be expensive and replacement parts aren’t cheap.

Be prepared for the poor brakes on the 3.8, which weren’t really up to the job when the car was new, so twenty or so years on they’re not likely to be very impressive and will very much depend on the condition of the servo. You’ll need a strong right foot! The rack and pinion steering is a delight and you’ll certainly be impressed by its precision and, above all, its lightness.

The six is a strong, reliable unit and quite capable of exceeding 100,000 miles (160,930km) between overhauls. The best way of evaluating its condition is to drive around in top gear at about 40 to 50mph (64 to 80kph) for a time and then sharply depress the accelerator. If the engine is in a good state, you should only be able to see a light exhaust haze in the rear view mirror. If, on the other hand, there are clouds of blue smoke, the car is suffering from excessive bore wear.

Now come the all-important checks on that potentially troublesome independent rear-suspension. Make a point of listening out for clunks or clicks, as a result of backing the accelerator pedal on and off. This could indicate a variety of maladies, including worn universal half-shaft joints, slack in the rear splines or wear in the bottom pivots of the stub axles. Be aware of a tendency for the car to steer from the rear. If this shortcoming is apparent, it is probably caused by the worn differential mountings mentioned earlier.

But finally a word of warning. Don’t be tempted to put your foot down hard on the accelerator as the E-type’s legendary performance can catch you unawares, particularly because the car’s speed can be deceptive. So don’t overdo it.

Much the same remarks apply to the Series III V12-powered cars, with the exception of the engine. Like the six, it is a robust and untemperamental unit. Before starting the engine, grasp the water pump pulley and see if there is any undesirable slack present. Once you’ve started it, listen out for a rattle from the front of the engine, which may indicate a worn timing chain. This is a particular problem associated with the V12 and some engines have been known to display this malady after only covering 35,000 miles (56,325km). You’re listening for the chain rubbing on the timing chest, particularly while revving up and on the over-run. In addition, keep your ears open for any bearing rattles as worn shells may not show up by a low reading on the oil pressure gauge. This should, incidentally, be not less than 60psi at 3,500rpm.

Be suspicious of an engine that has suffered recent water loss. The V12 is a little prone to overheating, a shortcoming that was often caused by a failure of the thermostatically-controlled fan to operate. This could result in a blown cylinder head gasket, or gaskets, and if this was not attended to, the heads could weld themselves to the block. Not a pleasant thought! A misfire usually relates to problems with the OPUS electronic ignition system.

After you’ve driven the car, park it and subsequently move it and check for oil leaks. The V12 is a little prone to wear in the crankshaft oil seal, which can deposit lubricant at around the point where the engine joins the gearbox bellhousing. Although the new seal itself is not expensive, the engine has to be removed to fit it, which is.

If you’ve set your heart on an E-type, there doesn’t seem to be any shortage of examples, so it is well worth shopping around. A perusal of the classified advertising columns of the specialist motoring press in such magazines as Classic Cars, Classic and Sportscar, Practical Classics, Motor Sport and Jaguar Quarterly is well worthwhile, don’t overlook the weekly Exchange and Mart and even your local newspaper.

It is also well worth going along to a meeting organised by one of the Jaguar clubs. There you’ll be able to talk to enthusiasts about their cars and the snags involved in running and restoring them. This brings us to parts availability, which is also considered in the next chapter.

JAGUAR E-TYPE 3.8-LITRE 1961–1964 PRINCIPAL MODIFICATIONS

Chassis nos. begin Open Two-Seater (OTS), RHD from 850001/LHD 875001

Chassis nos. begin Fixed-Head Coupe (FHC), RHD from 860001/LHD 885001

August 1961

LHD/RHD

(OTS 850048/875133) Front wheel hubs, introduction of water shields

October

(OTS 850092/875386, FHC 86005/885021) Higher output dynamo. New bonnet catches located inside car

January 1962

(OTS 850291/876130, FHC 860033/885210) Mintex brake pads adopted in place of M 40 linings

May

(FHC) Electrically heated rear window option available (OTS) Hard-top available

June

(OTS 850358/876582, FHC 860176/885504) Heel wells introduced in front floor (FHC 860479/886014) Modified tail lamps

October

Rear axle ratio changed to 3.31:1 on US and Canadian cars and to 3.07:1 on UK and other markets

June 1963

(OTS 850722/879494, FHC 861185/888706-UK) Mintex M59 brake pads adopted. Thickness of rear disc increased. Modified differential unit

September

(OTS 850737/879821, FHC 861226/889003) 3.31:1 rear axle ratio introduced for UK market

November

(OTS 850768/880291) Boot lock modified, following breakage of interior cable. New lock operated through hole in number plate panel

March 1964

(OTS 850809/880840, FHC 861446/889787) Interior door trim modified to improve appearance and ease of fitting

March

(Engine no. RA–4975) Full flow oil-filter introduced

April

(Engine no. RA 5735) E-type and Mark II cylinder heads commonised

May

(Engine no. RA 5801) Diaphragm clutch introduced

The V12-engined roadster, without its hard-top, and appreciating.

JAGUAR E-TYPE 4.2-LITRE (Series I) 1964–1968 PRINCIPAL MODIFICATIONS

Chassis nos. begin Open Two-Seater (OTS), RHD 1E.1001/LHD 1E.10001

Chassis nos. begin Fixed-Head Coupe (FHC), RHD 1E.2001/LHD 1E.30001

Chassis nos. begin Fixed-head Coupe (2 + 2) RHD 1E.50001/LHD 1E.75001

June 1965

LHD/RHD

(OTS 1E.1152/1E.10703, FHC 1E.20329/IE.30772) 3.07:1 final drive ratio on cars adopted for all countries, except North America which are fitted with 3.54:1 ratio

(OTS 1E. 1226/1E. 10958, FHC 1E.20612/1E.30912) Aperture on right-hand side of gearbox side panel to give access to speedometer drive

September

(OTS 1E.1253/1E.11049, FHC 1E.20692/1E.31078) Revised oil breather fitted

November

(FHC 1E.20852/1E.31413) Self locking rear door prop introduced

(Engine No. 7E.5170) Felt oil-filter replaced by paper element

March 1966

(OTS 1E.1413/1E.11535, FHC 1E.20993/1E.31765) Seven tooth pinion fitted to steering gear in place of eight tooth one previously employed

(OTS 1E.1409/1E.11715, FHC 1E.20978/1E.32009) Dunlop SP.41 HR tyres fitted

(OTS 1E.1413/1E.11741, FHC 1E.21000/1E.32010) Rear bumper fixing accessible from exterior of car. Hitherto only accessible from petrol tank and spare wheel area

September

(OTS 1E.1479/1E.12580, FHC 1E.21228/1E.32632) Bonnet and front wings, bumpers and heater intake commonised with 2 + 2 models

December

(OTS 1E.1545/1E.12965, FHC 1E.21335/1E.32888) Exhaust down pipes fitted with heat shield

July 1968

(Engine nos. 7E.13501 and 2 + 2, 7E.53582) Laycock clutch replaced by Borg and Beck diaphragm spring clutch 2 + 2 1E.50875/1E. 77407 Larger diameter torsion bars

(OTS 1E.1814/1E.15487, FHC 1E.21518/1E.34339, 2 + 2 1E.50912/1E.77475

Chrome wire wheels fitted with forged hub (OTS 1E.1853/1E.15753, FHC 1E.21579/1E.34458, 2 + 2 1E.50972/1E.77602) Silver painted wire wheels fitted with forged hub

JAGUAR E-TYPE 4.2-LITRE (Series II) 1968–1971 PRINCIPAL MODIFICATIONS

Chassis nos. begin Open Two-Seater (OTS), RHD 1R.1001/LHD 1R.7001

Chassis nos. begin Fixed-Head Coupe (FHC), RHD 1R.20001/LHD 1R.25001

Chassis nos. begin Fixed-Head Coupe (2 + 2), RHD 1R.35001/LHD 1R.40001

December 1968

(OTS 1R.1085, FHC 1R.20095, 2 + 2 1R.35099) Steering lock on RHD cars

January 1969

LHD/RHD

(OTS 1R.1013/1R.7443, FHC 1R.20007/1R.25284, 2 + 2 1R.35011/1R.40208) Lucas 11AC alternator introduced with side entry cables

March

(OTS 1R.1054, FHC 1R.20073, 2 + 2, 1R.35099) Non-eared hub caps fitted to RHD cars, bring them into line with LHD cars (OTS 1R.1068/1R.7993, FHC 1R.20119/1R.25524, 2 + 2 1R.35798/1R.40668) Modifications to upper panel of petrol tank

April

(OTS 1R.9860, FHC 1R.26533, 2 + 2 1R.42382) Ignition/starter switch with load shedding facility introduced on LHD cars

May

(OTS 1R.1138/1R.8869, FHC 1R.20212/1R.26005) Perforated leather trim and improved head rests introduced

June

(OTS 1R.118/1R.9570, FHC 1R.20270/1R.26387, 2 + 2 1R.35353/1R.42118) Gas filled bonnet stay, replacing spring

August

(Engines nos. 7R.6306 and 7R.38106) New position for engine number, being stamped on crankcase bell housing flange adjacent to dip stick on left-hand side of engine

October

(OTS 1R.1351/1R.10537, FHC 1R.24425/1R.26835, 2 + 2, 1R.35564/1R.42677) Battery operated clock introduced to replace mercury cell unit

November

(Engines nos. 7R.8688, 7R.8855) New camshafts with redesigned profiles

May 1970

(2 + 2 1R.35816/1R.43924) Handbrake revised with longer lever and angled end

August

(OTS 1R.1776, FHC 1R.20955) Larger diameter torsion bars on RHD cars

December

(Engine no., 14269) Suffix letters introduced following engine number to denote compression ratio: H – High Compression, S – Standard Compression, L – Low Compression

JAGUAR E-TYPE 5.3-LITRE (Series III) 1971–1975 PRINCIPAL MODIFICATIONS

Chassis nos. begin Open Two-Seater (OTS), RHD 1S1001/LHD 1S2001

Chassis nos. begin 2 + 2 RHD 1S50001/LHD 1S70001

November 1971

(OTS 1S.1093/1S.20099, 2 + 2 1S.50592/1S.72332) 3.31:1 crown wheel and pinion modified

December

(Engine no. 7S.4510) Crankshaft thrust washer revised

(OTS 1S.1152/1S.20122, FHC 1S.50872/1S.72357) Handbrake now common to LHD and RHD cars

March

(OTS 1S.1163/1S.20135, 2 + 2 1S.50875/1S.72450) Demister flap operated by cable and connecting rods, instead of cable and pinion previously employed

April 1972

3.07:1 axle ratio available as option on cars with manual gearbox

May

(Engine no. 7S.6310) Lighter pistons introduced

June

(OTS 1S.1348/1S.20569, 2 + 2 IS.51263/1S.73372) Larger cam profile on torsion bar

(Engine no. 7S.7155) Shell bearings on big end bearings modified to delete oil feed holes

October

(Engine no. 7S.7856) Oil feed in connecting rod small end deleted

December

(OTS 1S.1443/1S.20921, 2 + 2 1S.51318/1S.73372) Revised pinion valve on steering gear.

February 1973

(Engine no. 7S.9715) Modified Borg-Warner Model 12 gearbox, as available on XJ12 saloon, introduced

April

(OTS 1S.1663/1S.212606, 2 + 2 1S.51610/1S.74266) Air ducts to rear brakes modified to improve ground clearance and now fitted at factory rather than by dealer

May

(Engine no. 7S.10799) Crankshaft, as fitted to engine in V12 saloon, introduced

1974

(OTS 1S.23240, 2 + 2 1S.74586) Rubber overriders introduced on cars destined for American market