A

Critical Exam Information

|

A

Critical Exam Information

|

Get some moderate exercise Find time to go for a jog, lift weights, take a swim, or do whatever workout routine

works best for you.

Get some moderate exercise Find time to go for a jog, lift weights, take a swim, or do whatever workout routine

works best for you. Eat smart and healthy If you eat healthy food, you’ll feel good—and feel better about yourself. Be certain

to drink plenty of water, and don’t overdo the caffeine.

Eat smart and healthy If you eat healthy food, you’ll feel good—and feel better about yourself. Be certain

to drink plenty of water, and don’t overdo the caffeine. Get your sleep A well-rested brain is a sharp brain. You don’t want to sit for your exam feeling

tired, sluggish, and worn out.

Get your sleep A well-rested brain is a sharp brain. You don’t want to sit for your exam feeling

tired, sluggish, and worn out. Time your study sessions Don’t overdo your study sessions—long cram study sessions aren’t that profitable.

In addition, try to study at the same time every day at the time your exam is scheduled.

Time your study sessions Don’t overdo your study sessions—long cram study sessions aren’t that profitable.

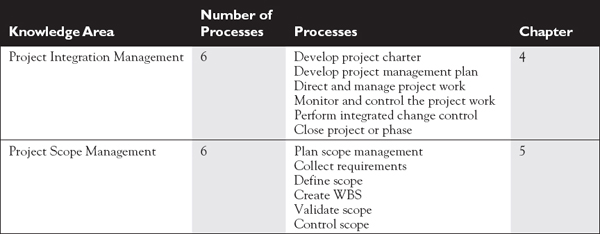

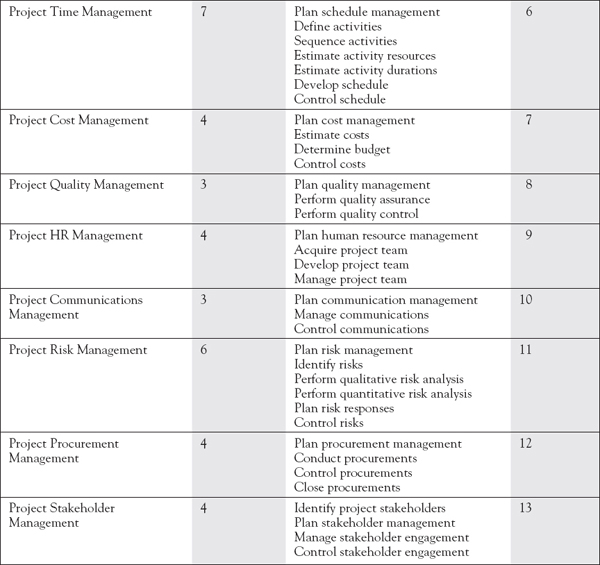

In addition, try to study at the same time every day at the time your exam is scheduled. Activities within each process group

Activities within each process group Estimating formulas

Estimating formulas Communication formula

Communication formula Normal distribution values

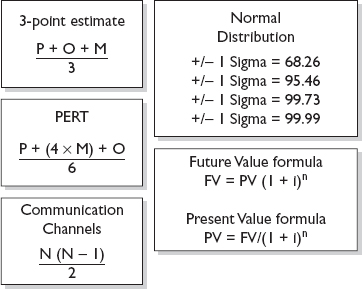

Normal distribution values Earned value management formulas

Earned value management formulas Project management theories

Project management theories

Functional

Functional Weak matrix

Weak matrix Balanced matrix

Balanced matrix Strong matrix

Strong matrix Projectized

Projectized Define activities

Define activities Cost estimating

Cost estimating Cost budgeting

Cost budgeting Identify risks

Identify risks Perform qualitative risk analysis

Perform qualitative risk analysis Benefit measurement methods These include scoring models, cost-benefit ratios, and economic models.

Benefit measurement methods These include scoring models, cost-benefit ratios, and economic models. Constrained optimization These include mathematical models based on linear, integer, and dynamic programming.

(This probably won’t be on the PMP exam as a viable answer.)

Constrained optimization These include mathematical models based on linear, integer, and dynamic programming.

(This probably won’t be on the PMP exam as a viable answer.) Product scope Defines the attributes of the product or service the project is creating

Product scope Defines the attributes of the product or service the project is creating Project scope Defines the required work of the project to create the product

Project scope Defines the required work of the project to create the product Lag Waiting between activities.

Lag Waiting between activities. Lead Activities come closer together and even overlap.

Lead Activities come closer together and even overlap. Free float The amount of time an activity can be delayed without delaying the next scheduled

activity’s start date.

Free float The amount of time an activity can be delayed without delaying the next scheduled

activity’s start date. Total float The amount of time an activity can be delayed without delaying the project’s finish

date.

Total float The amount of time an activity can be delayed without delaying the project’s finish

date. Float Sometimes called slack—a perfectly acceptable synonym.

Float Sometimes called slack—a perfectly acceptable synonym. Duration May be abbreviated as “du.” For example, du = 8d means the duration is eight days.

Duration May be abbreviated as “du.” For example, du = 8d means the duration is eight days. Mandatory This hard logic requires a specific sequence between activities.

Mandatory This hard logic requires a specific sequence between activities. Discretionary This soft logic prefers a sequence between activities.

Discretionary This soft logic prefers a sequence between activities. External Due to conditions outside of the project, such as those created by vendors, the

sequence must happen in a given order.

External Due to conditions outside of the project, such as those created by vendors, the

sequence must happen in a given order. Bottom-up Project costs start at zero, each component in the WBS is estimated for costs,

and then the “grand total” is calculated. This is the longest method to complete,

but it provides the most accurate estimate.

Bottom-up Project costs start at zero, each component in the WBS is estimated for costs,

and then the “grand total” is calculated. This is the longest method to complete,

but it provides the most accurate estimate. Analogous Project costs are based on a similar project. This is a form of expert judgment,

but it is also a top-down estimating approach, so it is less accurate than a bottom-up

estimate.

Analogous Project costs are based on a similar project. This is a form of expert judgment,

but it is also a top-down estimating approach, so it is less accurate than a bottom-up

estimate. Parametric modeling Price is based on cost per unit; examples include cost per metric ton, cost per

yard, and cost per hour.

Parametric modeling Price is based on cost per unit; examples include cost per metric ton, cost per

yard, and cost per hour. Variable costs The costs are dependent on other variables. For example, the cost of a food-catered

event depends on how many people register to attend the event.

Variable costs The costs are dependent on other variables. For example, the cost of a food-catered

event depends on how many people register to attend the event. Fixed costs The cost remains constant throughout the project. For example, a rented piece of

equipment requires the same fee each month, even if it is used more in some months

than in others.

Fixed costs The cost remains constant throughout the project. For example, a rented piece of

equipment requires the same fee each month, even if it is used more in some months

than in others. Direct costs The cost is directly attributed to an individual project and cannot be shared with

other projects (for example, airfare to attend project meetings, hotel expenses, and

leased equipment that is used only on the current project).

Direct costs The cost is directly attributed to an individual project and cannot be shared with

other projects (for example, airfare to attend project meetings, hotel expenses, and

leased equipment that is used only on the current project). Indirect costs These are the costs of doing business; examples include rent, phone, and utilities.

Indirect costs These are the costs of doing business; examples include rent, phone, and utilities. Ishikawa diagrams (also called fishbone diagrams) are used to find causes and effects that contribute to a problem.

Ishikawa diagrams (also called fishbone diagrams) are used to find causes and effects that contribute to a problem. Flow charts show the relationship between components and the flow of a process through a system.

Flow charts show the relationship between components and the flow of a process through a system. Pareto diagrams identify project problems and their frequencies. These are based on the 80/20 rule:

80 percent of project problems stem from 20 percent of the work.

Pareto diagrams identify project problems and their frequencies. These are based on the 80/20 rule:

80 percent of project problems stem from 20 percent of the work. Control charts plot out the result of samplings to determine whether projects are “in control” or

“out of control.”

Control charts plot out the result of samplings to determine whether projects are “in control” or

“out of control.” Kaizen technologies comprise approaches to make small improvements in an effort to reduce costs and achieve

consistency.

Kaizen technologies comprise approaches to make small improvements in an effort to reduce costs and achieve

consistency. Just-in-time ordering reduces the cost of inventory, but requires additional quality because materials

would not be readily available if mistakes occur.

Just-in-time ordering reduces the cost of inventory, but requires additional quality because materials

would not be readily available if mistakes occur. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs There are five layers of needs for all humans: physiological, safety, social (such

as love and friendship), self-esteem, and the crowning jewel, self-actualization.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs There are five layers of needs for all humans: physiological, safety, social (such

as love and friendship), self-esteem, and the crowning jewel, self-actualization. McClelland’s Theory of Needs Needs are developed by the person’s life experiences and may shift over time. Of

the three needs that drive people—power, affiliation, and achievement—one of these

is the most prominent in the individual. McClelland developed the Thematic Apperception

Test to determine what needs are driving individuals.

McClelland’s Theory of Needs Needs are developed by the person’s life experiences and may shift over time. Of

the three needs that drive people—power, affiliation, and achievement—one of these

is the most prominent in the individual. McClelland developed the Thematic Apperception

Test to determine what needs are driving individuals. Herzberg’s Theory of Motivation There are two catalysts for workers: hygiene agents and motivating agents.

Herzberg’s Theory of Motivation There are two catalysts for workers: hygiene agents and motivating agents. Hygiene agents do nothing to motivate, but their absence demotivates workers. Hygiene agents are

the expectations all workers have: job security, a paycheck, clean and safe working

conditions, a sense of belonging, civil working relationships, and other basic attributes

associated with employment.

Hygiene agents do nothing to motivate, but their absence demotivates workers. Hygiene agents are

the expectations all workers have: job security, a paycheck, clean and safe working

conditions, a sense of belonging, civil working relationships, and other basic attributes

associated with employment. Motivating agents are the elements that motivate people to excel. They include responsibility, appreciation

of work, recognition, opportunity to excel, education, and other opportunities associated

with work other than just financial rewards.

Motivating agents are the elements that motivate people to excel. They include responsibility, appreciation

of work, recognition, opportunity to excel, education, and other opportunities associated

with work other than just financial rewards. McGregor’s Theory of X and Y This theory states that “X” people are lazy, don’t want to work, and need to be

micromanaged and “Y” people are self-led, motivated, and can accomplish things on

their own.

McGregor’s Theory of X and Y This theory states that “X” people are lazy, don’t want to work, and need to be

micromanaged and “Y” people are self-led, motivated, and can accomplish things on

their own. Ouchi’s Theory Z This theory holds that workers are motivated by a sense of commitment, opportunity,

and advancement. Workers will work if they are challenged and motivated. Think participative

management.

Ouchi’s Theory Z This theory holds that workers are motivated by a sense of commitment, opportunity,

and advancement. Workers will work if they are challenged and motivated. Think participative

management. Expectancy Theory People will behave based on what they expect as a result of their behavior. In

other words, people will work in relation to the expected reward of the work.

Expectancy Theory People will behave based on what they expect as a result of their behavior. In

other words, people will work in relation to the expected reward of the work. Communication channels formula: N(N –1) / 2. N represents the number of stakeholders.

For example, if you have 10 stakeholders, the formula would read 10(10 –1) / 2 for

45 communication channels. Pay special attention to questions wanting to know how

many additional communication channels you have based on added stakeholders. For example,

if you have 25 stakeholders on your project and have recently added 5 team members,

how many additional communication channels do you now have? You’ll have to calculate

the original number of communication channels, 25(25 − 1) / 2 = 300; then calculate

the new number with the added team members, 30(30 − 1) / 2 = 435; and finally, subtract

the difference between the two: 435 − 300 = 135, the number of additional communication

channels.

Communication channels formula: N(N –1) / 2. N represents the number of stakeholders.

For example, if you have 10 stakeholders, the formula would read 10(10 –1) / 2 for

45 communication channels. Pay special attention to questions wanting to know how

many additional communication channels you have based on added stakeholders. For example,

if you have 25 stakeholders on your project and have recently added 5 team members,

how many additional communication channels do you now have? You’ll have to calculate

the original number of communication channels, 25(25 − 1) / 2 = 300; then calculate

the new number with the added team members, 30(30 − 1) / 2 = 435; and finally, subtract

the difference between the two: 435 − 300 = 135, the number of additional communication

channels. Fifty-five percent of communication is nonverbal.

Fifty-five percent of communication is nonverbal. Effective listening is the ability to watch the speaker’s body language, interpret

paralingual clues, and decipher facial expressions. Following the message, effective

listening has the listener asking questions to achieve clarity and offering feedback.

Effective listening is the ability to watch the speaker’s body language, interpret

paralingual clues, and decipher facial expressions. Following the message, effective

listening has the listener asking questions to achieve clarity and offering feedback. Active listening requires receivers of the message to offer clues, such as nodding

to indicate they are listening. It also requires receivers to repeat the message,

ask questions, and continue the discussion if clarification is needed.

Active listening requires receivers of the message to offer clues, such as nodding

to indicate they are listening. It also requires receivers to repeat the message,

ask questions, and continue the discussion if clarification is needed. Communication can be hindered by trendy phrases, jargon, and extremely pessimistic

comments. In addition, other communication barriers include noise, hostility, cultural

differences, and technical interruptions.

Communication can be hindered by trendy phrases, jargon, and extremely pessimistic

comments. In addition, other communication barriers include noise, hostility, cultural

differences, and technical interruptions. Business risk The loss of time and finances (where a downside and upside exist)

Business risk The loss of time and finances (where a downside and upside exist) Pure risk The loss of life, injury, and theft (where only a downside exists)

Pure risk The loss of life, injury, and theft (where only a downside exists) Avoidance Avoid the risk by planning a different technique to remove the risk from the project.

Avoidance Avoid the risk by planning a different technique to remove the risk from the project. Mitigation Reduce the probability or impact of the risk.

Mitigation Reduce the probability or impact of the risk. Acceptance The risk’s probability or impact may be small enough that the risk can be accepted.

Acceptance The risk’s probability or impact may be small enough that the risk can be accepted. Transference The risk is not eliminated, but the responsibility and ownership of the risk are

transferred to another party (for example, through insurance).

Transference The risk is not eliminated, but the responsibility and ownership of the risk are

transferred to another party (for example, through insurance). Exploit The organization wants to ensure that the identified risk does happen to realize

the positive impact associated with the risk event.

Exploit The organization wants to ensure that the identified risk does happen to realize

the positive impact associated with the risk event. Share Sharing is nice. When sharing, the risk ownership is transferred to the organization

that can most capitalize on the risk opportunity.

Share Sharing is nice. When sharing, the risk ownership is transferred to the organization

that can most capitalize on the risk opportunity. Enhance To enhance a risk is to attempt to modify its probability and/or its impacts to

realize the most gains from the identified risk.

Enhance To enhance a risk is to attempt to modify its probability and/or its impacts to

realize the most gains from the identified risk. Contingency funds Monies reserved for risk events.

Contingency funds Monies reserved for risk events. Secondary risks A risk that comes into a project as a direct result of another risk response.

Secondary risks A risk that comes into a project as a direct result of another risk response. Risk triggers A condition, event, or warning signs of a risk event that causes a risk reaction.

Risk triggers A condition, event, or warning signs of a risk event that causes a risk reaction. Residual risks Risks that remain after a risk response. These are usually small and are accepted

by the project team.

Residual risks Risks that remain after a risk response. These are usually small and are accepted

by the project team.

Stakeholder identification and documentation should happen as early as possible

in the project. This process is part of project initiation.

Stakeholder identification and documentation should happen as early as possible

in the project. This process is part of project initiation. You’ll need a stakeholder management plan to define the direction and strategy for

managing and engaging the stakeholders. This plan works along with the project’s communication

management plan.

You’ll need a stakeholder management plan to define the direction and strategy for

managing and engaging the stakeholders. This plan works along with the project’s communication

management plan. Stakeholder engagements mean that you’ll work with the stakeholders to maintain

their interest and support of the project. You’ll address their needs, concerns, perceived

threats, and even their pet requirements. The goal is to maintain stakeholder buy-in

of the project.

Stakeholder engagements mean that you’ll work with the stakeholders to maintain

their interest and support of the project. You’ll address their needs, concerns, perceived

threats, and even their pet requirements. The goal is to maintain stakeholder buy-in

of the project. Everything in a project is iterative, including the planning and controlling of

stakeholder engagement. If a stakeholder management strategy isn’t working, revisit

planning and find a new way to communicate and engage the project stakeholders.

Everything in a project is iterative, including the planning and controlling of

stakeholder engagement. If a stakeholder management strategy isn’t working, revisit

planning and find a new way to communicate and engage the project stakeholders. Stakeholders aren’t just the recipients of the project work. You must also work

to engage the project team, vendors, and stakeholders that have little interest or

influence over your project. Yes, you’ll prioritize based on power and influence,

but don’t forget to keep all of the stakeholders engaged.

Stakeholders aren’t just the recipients of the project work. You must also work

to engage the project team, vendors, and stakeholders that have little interest or

influence over your project. Yes, you’ll prioritize based on power and influence,

but don’t forget to keep all of the stakeholders engaged.