|

5

Managing the Project Scope

|

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVES

Have you ever set out to clean your garage and ended up cleaning your attic? It usually

starts by needing to move the car out of the garage so you can really dig in and clean.

As you move your car, you realize the car could really use a cleaning, too.

So you clean out the car. You dust it down; clean the windows inside and out; and

vacuum out pennies, old pens, and some green French fries. The vacuum, you discover,

has something caught in the hose, so you have to fight to clear the blockage in order

to finish cleaning out the car. Once the inside’s spick-and-span, you think, “Might

as well wash and wax the car, too.”

This calls for the garden hose. The garden hose, you notice, is leaking water at the

spigot by the house. Now you’ve got to replace the connector. This calls for a pair

of channel-lock pliers. You run to the hardware store, get the pliers—and some new

car wax. After fixing the garden hose, you finally wash and wax the car.

As you’re putting on the second coat of wax, you see a few scratches on the car that

could use some buffing. You have a great electric buffer but can’t recall where it

is. Maybe it’s in the attic? You check the attic only to realize how messy things

are there, too. So you begin moving out old boxes of clothes, baby toys, and more

interesting stuff.

Before you know it, the garage is full of boxes you’ve brought down from the attic.

The attic is somewhat cleaner, but the garage is messier than when you started this

morning. As you admire the mess, you realize it’s starting to rain on your freshly

waxed car, the garden hose is tangled across the lawn, and there are so many boxes

in the garage you can’t pull the car in out of the rain.

So what does this have to do with project management? Plenty! Project management requires

focus, organization, and a laser-like concentration. In this chapter, we’ll be covering

project scope management: the ability to get the required work done—and only the required

work—to complete the project. We’ll look at how a project manager should create and

follow a plan to complete the required work to satisfy the scope without wandering

or embellishing on the project deliverables.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 5.01

Planning Project Scope Management

This first process in project scope management is to create the scope management plan, which defines how the project scope will actually be defined, the techniques you

and the project team will use to validate the scope, and what approach is in place,

or will be created, to control changes to the scope. Project scope management has

several purposes:

It defines what work is needed to complete the project objectives.

It defines what work is needed to complete the project objectives. It determines what is included in the project.

It determines what is included in the project. It serves as a guide to determine what work is not needed to complete the project

objectives.

It serves as a guide to determine what work is not needed to complete the project

objectives. It serves as a point of reference for what is not included in the project.

It serves as a point of reference for what is not included in the project.So what is a project scope statement? A project scope statement is a description of

the work required to deliver the product of a project. The project scope statement

defines what work will, and will not, be included in the project work. A project scope

guides the project manager on decisions to add, change, or remove the work of the

project.

When it comes to project scope management, as in the bulk of this chapter, focus on

the required work to complete the project according to the project plan. The product

scope, meanwhile, is specific to the deliverable of the project. Just remember that

the exam will focus on project scope management.

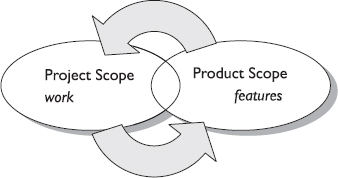

Project Scope vs. Product Scope

Project scope and product scope are different entities. A project scope deals with

the work required to create the project deliverables. For instance, a project to create

a new barn would focus only on the work required to complete the barn with the specific

attributes, features, and characteristics called for by the project plan. The scope

of the project is specific to the work required to complete the project objectives.

Product scope, on the other hand, is the attributes and characteristics of the deliverables

the project is creating. For the barn project, the product scope would define the

features and attributes of the barn. In this instance, the project to create a barn

would not include creating a flower garden, a wading pool, and the installation of

a fence. There would be very specific requirements regarding the features and characteristics

of the barn: the materials to be used, the dimensions of the different rooms and stalls,

the expected weight the hayloft should carry, electrical requirements, and more.

Just to be clear, the product scope describes the exact features and functions of

the product. The project scope defines the work that your project team and vendors

must complete in order for the project to be done. The project scope is based on the

product scope. The project’s execution completes the project scope, which in turn

creates the features and functions of the product scope.

The project scope and the product scope are bound to each other. The product scope

constitutes the characteristics and features of the product that the project creates.

The end result of the project is measured against the requirements for that product.

The project scope is the work required to deliver the product. Throughout the project

execution, the work is measured against the project plan to verify that the project

is on track to fulfill the product scope. The product scope is measured against requirements,

while the project scope is measured against the project plan.

Creating the Project Scope Management Plan

Planning the project scope involves progressive elaboration. The project scope begins

broad and through refinement becomes focused on the required work to create the product

of the project. The project manager and the project team must examine the product

scope—what the customer expects the project to create—to plan on how to achieve that

goal. Based on the project requirements documentation, the project scope can be created.

The scope planning process will use expert judgment and meetings. Experts can include

people from inside your organization and may include consultants and vendors who contribute

to this portion of the project planning. Most likely, your experts will include the

project team because they are closest to the project work, the customers because they’re

driving the content of the product scope, and other stakeholders that have influence

over the project direction.

The planning meetings’ approach is really part of the organization’s culture. Consider,

for example, what work is like for a project manager in a bank versus a project manager

in a small, entrepreneurial company. The culture of both entities differs regarding

how a project is initiated, planned, and then managed. Of course, the project charter,

the requirements documentation, and organizational process assets will guide the scope

planning process as well.

Using Scope Planning Tools and Techniques

The goal of scope planning is to create a project scope statement and the project

scope management plan, two of the outputs of the scope planning process. The project

manager and the project team must have a full understanding of the project requirements,

the business need of the project, and stakeholder expectations to be successful in

creating the scope statement and the scope management plan. Recall that there are

two types of scope:

Product scope Features and functions of the product of the project

Product scope Features and functions of the product of the project Project scope The work needed to create the product of the project

Project scope The work needed to create the product of the projectThe project manager and the project team can rely on two tools to plan the project

scope. The first is expert judgment—using someone smarter than the project team, the

project manager, and even the key stakeholders to guide the scope planning process.

Expert judgment can come from experts within the organization or third-party experts,

such as consultants. Second, the project manager can rely on the templates, forms,

and standards an organization may provide. Common templates and forms for projects

include work breakdown structure templates, scope management plan templates, and project

scope change control forms. Standards are guidelines that an organization has created

to direct project teams in their scope planning endeavors.

Creating the Scope Management Plan

The scope management plan explains how the project scope will be managed and how scope

changes will be factored into the project plan. Based on the conditions of the project,

the project work, and the confidence of the exactness of the project scope, the scope

management plan should also define the likelihood of changes to the scope, how often

the scope may change, and how much the scope can change. The scope management plan

also details the process of how changes to the project scope will be documented and

classified throughout the project life cycle. Every scope management plan should define

four things:

The process to create the project scope statement

The process to create the project scope statement The process to create the work breakdown structure (WBS) based on the project scope

statement—and the methods for maintaining the WBS integrity and the process for WBS

approval

The process to create the work breakdown structure (WBS) based on the project scope

statement—and the methods for maintaining the WBS integrity and the process for WBS

approval The process for formal acceptance of the project deliverables by the project customer

The process for formal acceptance of the project deliverables by the project customer The process for evaluating and approving or declining project change requests

The process for evaluating and approving or declining project change requests

Generally, you do not want the project scope to change. The implication of the scope

management plan concerns how changes to the project scope will be permitted and what

the justification is to allow the change. In an Agile environment, changes are expected

as part of the project management framework, something to watch for on your PMP exam.

The process of creating the scope management plan also creates the requirements management

plan, which defines how you and the project team will collect, document, and protect

the project requirements. The requirements management plan defines configuration management

for the product and the tracking approach you’ll utilize in this project. This plan

also defines how requirements may be prioritized, any metrics for requirements measurements,

and the requirements traceability matrix.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 5.02

Collecting and Eliciting Project Requirements

Projects don’t exist without stakeholders. Sure, sure, sometimes they are a pain in

the neck, but if it weren’t for them, there would not be a reason to have projects—or

project managers. Stakeholders and project managers need to work together as a team;

the stakeholders know what they want as the end result of your work, and the project

manager and the project team can make that end result a reality. The project manager’s

role is to elicit requirements from the stakeholders to create the best possible solution

to satisfy the needs of the stakeholders, the organization, and the longevity of the

solution.

In some places, such as the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA), the

process of gathering requirements is not the responsibility of the project manager,

but of a business analyst. The goal, whether the project manager or a business analyst

is leading the work, is the same: Find detailed specifications about exactly what

the stakeholders want and expect from the project. Once the requirements have been

identified—clearly identified—the project manager and team can work toward specific

results. Loose, open-ended, foggy requirements waste time, money, and effort. You’ll

be gathering broad categories of requirements:

Business requirements These define why the project has been initiated and what are the high-level expectations

for the project.

Business requirements These define why the project has been initiated and what are the high-level expectations

for the project. Stakeholder requirements These are the individual stakeholder and stakeholder group requirements for the

project.

Stakeholder requirements These are the individual stakeholder and stakeholder group requirements for the

project. Solution requirements These describe the features, function, and characteristics of the project deliverable.

Solution requirements really are described by two subrequirement categories:

Solution requirements These describe the features, function, and characteristics of the project deliverable.

Solution requirements really are described by two subrequirement categories: Functional requirements These describe how the solution will work, what the solution will manage, and all

the capabilities the solution will provide for the stakeholder. It’s how your project

deliverable will operate.

Functional requirements These describe how the solution will work, what the solution will manage, and all

the capabilities the solution will provide for the stakeholder. It’s how your project

deliverable will operate. Nonfunctional requirements These describe the conditions that the functional requirements must operate within.

You might hear this also described as the quality requirements or environmental requirements,

where the solution will operate at its ideal level or performance. You can recognize

nonfunctional requirements when stakeholders talk about speed, capacity, security,

user interfaces, or production.

Nonfunctional requirements These describe the conditions that the functional requirements must operate within.

You might hear this also described as the quality requirements or environmental requirements,

where the solution will operate at its ideal level or performance. You can recognize

nonfunctional requirements when stakeholders talk about speed, capacity, security,

user interfaces, or production. Transition requirements These requirements describe the needed elements to move from the current state

to the desired future state—for example, training requirements or dual-supporting

systems.

Transition requirements These requirements describe the needed elements to move from the current state

to the desired future state—for example, training requirements or dual-supporting

systems. Project requirements The project may have requirements in the way it is managed, specific processes

that are to be followed, and other objectives that the project manager is obligated

to meet.

Project requirements The project may have requirements in the way it is managed, specific processes

that are to be followed, and other objectives that the project manager is obligated

to meet. Quality requirements Any condition, metric, performance objective, or condition the project must meet

in order to be considered of quality. These should be measurable and not ambiguous

goals.

Quality requirements Any condition, metric, performance objective, or condition the project must meet

in order to be considered of quality. These should be measurable and not ambiguous

goals.The project is the first step in requirements gathering, because it paints the high-level

objective of the project. Some project charters rely on a current state assessment

and compare it to the desired future state assessment. This is basically a project

before-and-after—your project deliverables create the future state. Other charters

simply define the high-level goals of the project, and then it’s up to you, your project

team, and any other experts to figure out how to make it happen.

You’ll also rely on the stakeholder registry to confirm that you’re communicating,

interviewing, and eliciting requirements from all of the stakeholders. Recall that

some stakeholders won’t want your project to succeed at all—those nasty, negative

stakeholders. Just because they despise the project doesn’t mean you get to ignore

them. You’ll need to work with both positive and negative stakeholders during requirements

gathering and throughout the project.

Interview the Stakeholders

One of the most reliable requirements-gathering methods is interviewing, which is a conversation between you and the project stakeholders about their needs,

wants, and demands for the project. It’s a learning process for you to absorb information

from the project customer by asking them questions. You need and want the interviewee

to talk to you, so you’ve got to ask questions. Let me rephrase that: You need to

ask good questions.

The interviewer should go into the interview armed with some questions that allow

the stakeholder to ramble a bit and other questions that allow the stakeholder to

be precise about the project deliverables. You probably aren’t going to ask the stakeholder

how to create the deliverable, but you’ll likely ask how they’ll be using the product

that you’ll be creating. You want to see how they’ll be using the deliverable as part

of their day-to-day lives. This is where you’ll categorize the requirements as functional

or nonfunctional.

Interviews are usually done one-on-one, but there’s no reason why a project manager

can’t have several interviewers participate in the session. As a general rule, however,

the more people who participate in the interview, the more complex the elicitation

process becomes. Smaller groups allow for a more conversational tone to the meeting.

Sometimes, however, the project manager will need a subject matter expert to help

the conversation along.

Leading a Focus Group

Focus groups are an opportunity for a group of stakeholders to interact with a project

moderator about the requirements of the project, the current state of an organization,

or how they’ll see the project deliverables affecting the organization once the project

is completed. Like an interviewer, the moderator is armed with questions, but he should

be well versed on the topic to branch into new contributing discussions on the project

requirements.

An ideal focus group has six to twelve people in one room, and the moderator should

encourage open, conversational discussion. The moderator, often not the project manager,

should be neutral to the project, have the ability to draw people into the conversation,

and keep the session on track to the goals of the project. A scribe or recorder should

document the discussion in the session so the project manager and team can review

the results of the meeting and act accordingly.

Hosting a Requirements Workshop

Let’s face facts: Sometimes stakeholders have agendas. And by sometimes, I mean they

always do. When you’re managing a project with stakeholders from across the organization,

you’ll be dealing with different departments, different functions, and different lines

of business. The stakeholders from each of these groups may have different expectations

and requirements for the project, and these expectations will often clash. A requirements

workshop, sometimes called a facilitated workshop, aims to find commonality, consensus,

and cohesion among the stakeholders for the project requirements.

If you’re in software development work, you’ve probably participated in a joint application

design (JAD) workshop. These strive to gather all the requirements and to create a

well-rounded, balanced application for all the stakeholders. In manufacturing, project

managers use a requirements workshop, sometimes called the voice of the customer (VOC),

where the voice of the customer dictates what the project will create. You might also

know VOC as quality function deployment (QFD). The idea is that quality is achieved

by giving the customer exactly what they expect.

Using Group Creativity Techniques

Rarely will all of the requirements for a project be clearly defined when the project

launches. There are probably some cases in which projects that are repeated over and

over, such as in manufacturing or construction, may be based on the same initial set

of requirements, but usually the requirements for each project vary wildly, because

each project is unique. When you’re managing a large project, you need to work with

groups of stakeholders to elicit their requirements for the project deliverables.

Sometimes stakeholders have a general idea of what they’d like you to create, but

they aren’t certain. Consider market opportunities; problems that need to be solved;

and implementations of new materials, software, or organization-wide changes.

The requirements in these instances can go in multiple directions and demand a good

plan and uniformity to create a successful project and useable deliverable.

When multiple solutions exist for a project, or the stakeholders aren’t entirely certain

what the exact project requirements should be, group creativity techniques can be

useful. These techniques help the key stakeholders generate ideas, solutions, and

requirements for the project. Here are some examples you should know for your PMP

exam:

Brainstorming Brainstorming is an anything-goes approach to idea generation. The group of participants

brainstorm about a topic and throw out as many ideas as possible to generate solutions

and requirements.

Brainstorming Brainstorming is an anything-goes approach to idea generation. The group of participants

brainstorm about a topic and throw out as many ideas as possible to generate solutions

and requirements. Nominal group technique Like brainstorming, this approach generates ideas, but then the ideas are voted

on by the stakeholders and ranked based on usefulness.

Nominal group technique Like brainstorming, this approach generates ideas, but then the ideas are voted

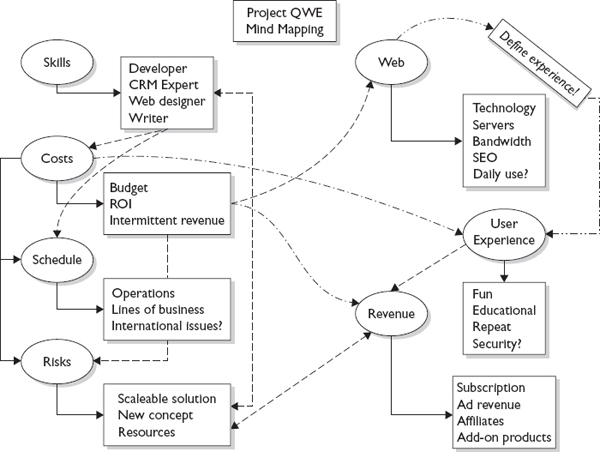

on by the stakeholders and ranked based on usefulness. Mind mapping Mind maps link ideas, thoughts, requirements, and objectives to one another. You

might use mind maps after a brainstorming or nominal group technique to organize possible

solutions and requirements, and to show where differences exist between the stakeholders

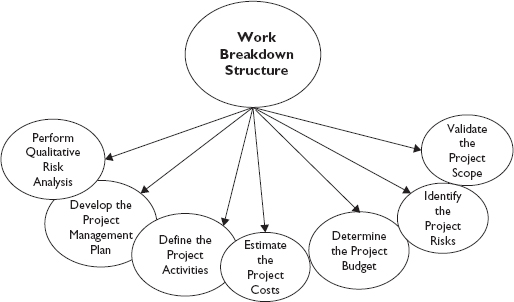

(see Figure 5-1).

Mind mapping Mind maps link ideas, thoughts, requirements, and objectives to one another. You

might use mind maps after a brainstorming or nominal group technique to organize possible

solutions and requirements, and to show where differences exist between the stakeholders

(see Figure 5-1).

FIGURE 5-1 Mind maps visualize project requirements while they’re being created.

Affinity diagram This group creativity technique is often used for solutions. It groups ideas into

clusters, each of which can be broken down again to analyze each subset. It’s basically

a decomposition and organization of project ideas and requirements.

Affinity diagram This group creativity technique is often used for solutions. It groups ideas into

clusters, each of which can be broken down again to analyze each subset. It’s basically

a decomposition and organization of project ideas and requirements. Multicriteria decision analysis This approach relies on a systematic approach of determining, ranking, and eliminating

project criteria such as performance metrics, risks, requirements, and other project

elements. These approaches use a table called a “decision matrix” to measure and score

these project elements.

Multicriteria decision analysis This approach relies on a systematic approach of determining, ranking, and eliminating

project criteria such as performance metrics, risks, requirements, and other project

elements. These approaches use a table called a “decision matrix” to measure and score

these project elements. Delphi Technique This approach uses rounds of anonymous surveys to foster consensus. Each round

of surveys is based on answers from the past round so each participant can freely

and anonymously comment on others’ thoughts and inputs about the project requirements.

The idea is that the comments will lead the group toward the most correct answer without

the political attachment that may occur if the process were not anonymous.

Delphi Technique This approach uses rounds of anonymous surveys to foster consensus. Each round

of surveys is based on answers from the past round so each participant can freely

and anonymously comment on others’ thoughts and inputs about the project requirements.

The idea is that the comments will lead the group toward the most correct answer without

the political attachment that may occur if the process were not anonymous. If you’re wondering why it’s called the Delphi Technique, it’s named after the Oracle

at Delphi—the most important oracle from Greek mythology. The technique was first

used in 1944 at the start of the Cold War to predict how technology may affect warfare.

If you’re wondering why it’s called the Delphi Technique, it’s named after the Oracle

at Delphi—the most important oracle from Greek mythology. The technique was first

used in 1944 at the start of the Cold War to predict how technology may affect warfare.Using Group Decisions

When many project stakeholders have loads of different competing objectives about

the project deliverables, it’s sometimes best for the project manager to hand the

decision back to the project stakeholders. This approach generally allows the majority

to vote on the project direction, but it doesn’t always garner goodwill, cohesion,

or buy-in from all the project stakeholders. There are four different models of group

decisions you should be familiar with:

Unanimity All of the stakeholders agree on the project requirements (and then rainbows appear,

the sun shines, and bluebirds sing).

Unanimity All of the stakeholders agree on the project requirements (and then rainbows appear,

the sun shines, and bluebirds sing). Majority This is probably the most common group decision, in which a vote is offered and

the majority wins.

Majority This is probably the most common group decision, in which a vote is offered and

the majority wins. Plurality Like a majority rule, this approach allows the biggest section of a group to win,

even if a majority doesn’t exist. You might experience this when there are three possible

solutions for the project and the stakeholders vote their opinion for each solution

in uneven thirds of 25 percent, 35 percent, and 40 percent. The group that represents

the 40 percent would win, even though more people (60 percent) are opposed to the

solution.

Plurality Like a majority rule, this approach allows the biggest section of a group to win,

even if a majority doesn’t exist. You might experience this when there are three possible

solutions for the project and the stakeholders vote their opinion for each solution

in uneven thirds of 25 percent, 35 percent, and 40 percent. The group that represents

the 40 percent would win, even though more people (60 percent) are opposed to the

solution. Dictatorship The project manager, project sponsor, or the person with the most power forces

the decision, even though the rest of the group may oppose the decision. No warm,

fuzzy feelings here.

Dictatorship The project manager, project sponsor, or the person with the most power forces

the decision, even though the rest of the group may oppose the decision. No warm,

fuzzy feelings here.Relying on Surveys

Surveys are a fine approach to eliciting requirements from a large group of stakeholders

in a relatively short amount of time. The challenge with surveys, however, is that

they must be responded to and tabulated, and the survey questions must be well written

to generate accurate responses. When the general requirements are known, closed-ended

questions are ideal, but you should restrict the type of information the respondent

may provide. Open-ended questions allow the respondent to write essays about a particular

topic, but it takes more time to tabulate the responses.

Survey writers need to determine the best type of questions, and they must consider

the audience of the survey. You’ll also want to consider how quickly you’d like respondents

to complete the survey and how you’ll collect and tabulate the results. Obviously,

electronic surveys are ideal, as you can quickly sort the data, create charts, and

track who has responded.

Observing Stakeholders

One of the best pieces of advice out there, when it comes to learning a new skill,

is this: It’s easier to watch someone peel a banana than describe how to peel a banana.

This is true in requirements gathering, too—by observing someone do their work, you

can see the processes, approaches, and challenges of their work more clearly than

by just hearing about their work. Observing stakeholders, especially when your project

is likely to affect their day-to-day work life, processes, and methods of operation

in your organization, is an excellent way to gather requirements.

As an observer, you shadow a person and watch how they do their work. You might complete

the shadowing as a passive or invisible observer. In this role, you work quietly,

stay out of the way, and take notes on the processes you see. As an active or visible

observer, you’re stopping the person doing the work, asking loads of questions, and

seeking to understand how the person is completing his work.

Creating Prototypes

Have you ever seen a model of a skyscraper, or what about a mockup for a new web site,

application, or even a brochure? These are prototypes that allow the stakeholder to see how the end result is going to function. Prototypes

help the project manager confirm that she understands the requirements the stakeholder

expects from the deliverable. Some prototypes are considered throw-away, and they

don’t really work beyond communicating the idea of the deliverable. Other prototypes

are considered functional or working and evolve into the final deliverable of the

project.

Benchmarking the Requirements

Benchmarking is an approach you can use throughout the project. Benchmarking compares two similar

things to see which is performing better. For example, you might compare Microsoft

SQL Server to an Oracle Server. Or you might compare two different pieces of equipment.

Benchmarking, in requirements collections, allows you to compare the requirements

for your project against organizations that have completed similar work to see how

their projects and products performed to help you better define what’s needed in your

project.

Utilizing a Context Diagram

Imagine your project is to install, configure, and roll out an organization-wide e-mail

and calendaring server. A context diagram would illustrate all of the components that

would interact with your server. It would show the other computers on the network,

the network itself, other servers, routers, switches, and other hardware. Then the

context diagram would show the people who interact with the server and their different

roles, such as administrators, users, and support personal. All of these things and

people that interact with the server are called actors in the context diagram.

Analyzing Project Documents

Consider a large project to construct a new office building in your city. This project

would involve letters, e-mails, blueprints and technical drawings, and more documentation.

Analyzing all of these documents helps the project manager and the project team capture

all of the requirements that need to be traced throughout the project. This isn’t

a particularly fast approach to capturing project requirements, but it helps to ensure

that all of the requirements are captured. Documents to inspect include marketing

literature, business plans, contracts, software and system documentation, issue logs,

and organizational process assets.

Managing the Project Requirements

The goal of eliciting the project requirements is to clearly identify and manage the

requirements so the project scope can be created and the in-depth project planning

can begin. It’s ever-so-important for the project manager, the project team, and the

key project stakeholders to be in agreement with the intent, direction, and requirements

of the project before the project scope is created. You should be familiar with three

outputs of the collect project requirements process:

Requirements documentation The clearly defined requirements must be measurable, complete, accurate, and signed-off

by the project stakeholders. The requirements documentation may start broad and, through

progressive elaboration, become more distinct, but the identification and agreement

of what is required and demanded of the project is paramount. This includes definition

of the functional and nonfunctional requirements, acceptance criteria, documentation

of the impact of the deliverable on the organization, and any assumptions or constraints

that have been identified.

Requirements documentation The clearly defined requirements must be measurable, complete, accurate, and signed-off

by the project stakeholders. The requirements documentation may start broad and, through

progressive elaboration, become more distinct, but the identification and agreement

of what is required and demanded of the project is paramount. This includes definition

of the functional and nonfunctional requirements, acceptance criteria, documentation

of the impact of the deliverable on the organization, and any assumptions or constraints

that have been identified. Requirements management plan The requirements management plan defines how requirements will be managed throughout

the phases of the project. This plan also defines how any changes to the requirements

will be allowed, documented, and tracked through project execution. You’ll also need

to prioritize the project requirements and define what metrics will be used to measure

requirement completion and acceptability.

Requirements management plan The requirements management plan defines how requirements will be managed throughout

the phases of the project. This plan also defines how any changes to the requirements

will be allowed, documented, and tracked through project execution. You’ll also need

to prioritize the project requirements and define what metrics will be used to measure

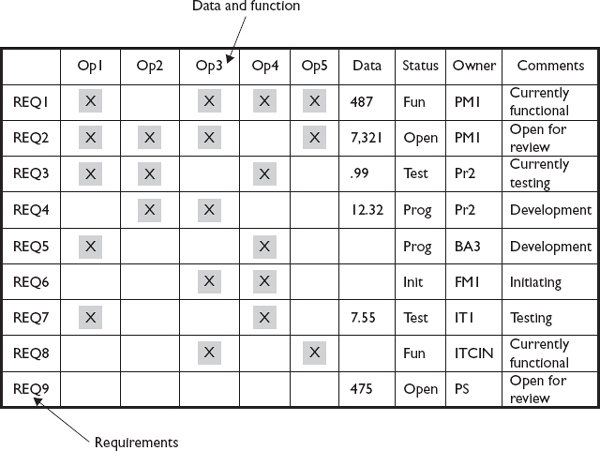

requirement completion and acceptability. Requirements traceability matrix (RTM) When you’re managing loads of requirements, an RTM can help you track several characteristics

for each requirement:

Requirements traceability matrix (RTM) When you’re managing loads of requirements, an RTM can help you track several characteristics

for each requirement: Requirement name

Requirement name Requirement’s link to the business and project objectives

Requirement’s link to the business and project objectives Function of each requirement

Function of each requirement Any relevant data, coding, cost, or schedule about a requirement

Any relevant data, coding, cost, or schedule about a requirement Requirement’s current status

Requirement’s current status Owner of the requirement

Owner of the requirement Comments or notes about the requirement

Comments or notes about the requirementAn RTM can help you ensure that every requirement in the project has been created

to specification. This will help in quality control processes and in scope validation

later in the project. Figure 5-2 is an example of an RTM.

FIGURE 5-2 An RTM can track elements and delivery of requirements.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 5.03

Defining the Project Scope Statement

The process of scope definition is all about breaking down the work into manageable

chunks. If you wanted to create a new house, you probably wouldn’t stop by the lumberyard;

pick up a truck of lumber, some cement, and nails; and set about building your dream

house. You’d follow a logical approach to designing, planning, and then creating the

house.

The same is true with project management. Your organization and stakeholders may have

a general idea of where the project should end up, but a detailed, fully developed

plan is needed to get you there. Scope definition is the process of breaking down

the broad vision for the project into logical steps to reach its completion.

Examining the Inputs to Scope Definition

You should be very familiar with the inputs to scope definition; you’ve seen these

several times already in the book. The following is a quick refresher of each input

and its role in this process:

Scope management plan The scope management plan defines the approach for creating the project scope statement.

Scope management plan The scope management plan defines the approach for creating the project scope statement. The project charter The project charter authorizes the project and the project manager.

The project charter The project charter authorizes the project and the project manager. Requirements documentation The project scope is founded on the requirements documentation, as this is what’s

expected of the project.

Requirements documentation The project scope is founded on the requirements documentation, as this is what’s

expected of the project. Organizational process assets The formal and informal guidelines, policies, and procedures that influence how

a project scope is managed.

Organizational process assets The formal and informal guidelines, policies, and procedures that influence how

a project scope is managed. You’ll rely on the project’s scope management plan, because it defines how the scope

will be defined, managed, and controlled. Once your project is in motion, you can

also expect change requests to influence the definition of your project scope.

You’ll rely on the project’s scope management plan, because it defines how the scope

will be defined, managed, and controlled. Once your project is in motion, you can

also expect change requests to influence the definition of your project scope.Using Product Analysis

Product analysis is, as the name implies, the process of analyzing the product the project will create.

Specifically, it involves understanding all facets of the product, its purpose, how

it works, and its characteristics. Product analysis can be accomplished through one

or more of the following:

Product breakdown Breaks down the product into components, examining each component individually

and how it may work with other parts of the product. This approach can be used in

chemical engineering to see how a product, such as a pharmaceutical, is created and

how effective it is.

Product breakdown Breaks down the product into components, examining each component individually

and how it may work with other parts of the product. This approach can be used in

chemical engineering to see how a product, such as a pharmaceutical, is created and

how effective it is. Systems engineering Focuses on satisfying the customers’ needs, cost requirements, and quality demands

through the design and creation of the product. An entire science is devoted to systems

engineering in various industries.

Systems engineering Focuses on satisfying the customers’ needs, cost requirements, and quality demands

through the design and creation of the product. An entire science is devoted to systems

engineering in various industries. Value engineering Deals with reducing costs and increasing profits, all while improving quality.

Its focus is on solving problems, realizing opportunities, and maintaining quality

improvement. Value engineering is also concerned with the customers’ perception of

the value of the different aspects of the product versus the project’s cost to create

the product’s features and functions.

Value engineering Deals with reducing costs and increasing profits, all while improving quality.

Its focus is on solving problems, realizing opportunities, and maintaining quality

improvement. Value engineering is also concerned with the customers’ perception of

the value of the different aspects of the product versus the project’s cost to create

the product’s features and functions. Value analysis Similar to value engineering, focuses on the cost/quality ratio of the product.

For example, your expected level of quality of a $100,000 automobile versus a $6700

used car is likely relevant to the cost of each. Value analysis focuses on the expected

quality against the acceptable cost.

Value analysis Similar to value engineering, focuses on the cost/quality ratio of the product.

For example, your expected level of quality of a $100,000 automobile versus a $6700

used car is likely relevant to the cost of each. Value analysis focuses on the expected

quality against the acceptable cost. Function analysis Related to value engineering, allows team input to the problem, institutes a search

for a logical solution, and tests the functions of the product so the results can

be graphed.

Function analysis Related to value engineering, allows team input to the problem, institutes a search

for a logical solution, and tests the functions of the product so the results can

be graphed. Quality function deployment A philosophy and practice to understand customer needs—both spoken and implied—fully,

without gold-plating the project deliverables.

Quality function deployment A philosophy and practice to understand customer needs—both spoken and implied—fully,

without gold-plating the project deliverables.Finding Alternatives

Project managers, project team members, and stakeholders must resist the temptation

to fall in love with a solution too quickly. Alternative identification is any method

of creating alternative solutions to the project’s needs. This is typically accomplished

through brainstorming and lateral thinking.

Consulting with Experts

Throughout the PMBOK Guide you’ll see references to “expert judgment.” It should come as no surprise that developing

the project scope also includes this tool and technique. The experts for the project

scope are the stakeholders, the customers, the users, and consultants to the project

work. For a project to be successful, the project manager and the project team must

know what the stakeholders of the project expect. This means communication must occur

between the project manager and the stakeholders. Business analysts may be involved

or even facilitate this process of scope definition, but the end result is the same:

The expectations of the project stakeholders must be identified, documented, and then

prioritized.

This is also the time to define what constitutes project success. Unquantifiable metrics,

such as customer satisfaction, “good,” and “fast,” don’t cut it. The project manager

and the stakeholders must agree on metrics that indicate a project’s success or failure.

These are the key performance indicators (KPIs) that projects are often measured against.

Examining the Scope Statement

The scope statement, an output of scope planning, is the guide for all future project decisions when

it comes to change management. It is the key document to providing understanding of

the project purpose. The scope statement provides justification for the project existence,

lists the high-level deliverables, and quantifies the project objectives. The scope

statement is a powerful document that the project manager and the project team will

use as a point of reference for potential changes, added work, and any project decisions.

The scope statement includes or references the following:

Product scope description Recall that the product scope description defines the characteristics and features

of the thing or service the project is aiming to create. In most projects, the product

scope will be vague early in the scope planning process, and then more details will

become available as the product scope is progressively elaborated.

Product scope description Recall that the product scope description defines the characteristics and features

of the thing or service the project is aiming to create. In most projects, the product

scope will be vague early in the scope planning process, and then more details will

become available as the product scope is progressively elaborated. Product acceptance criteria The scope statement defines the requirements for acceptance. Product acceptance

criteria establish what exactly qualifies a project’s product as a success or failure.

Product acceptance criteria The scope statement defines the requirements for acceptance. Product acceptance

criteria establish what exactly qualifies a project’s product as a success or failure. Project deliverables The high-level deliverables of the project should be identified. These deliverables,

when predefined metrics are met, signal that the project scope has been completed.

When appropriate, the scope statement should also list what deliverables are excluded

from the project deliverables. For example, a project to create a new food product

may state that it is not including the packaging of the food product as part of the

project. Items and features not listed as part of the project deliverables should

be assumed to be excluded.

Project deliverables The high-level deliverables of the project should be identified. These deliverables,

when predefined metrics are met, signal that the project scope has been completed.

When appropriate, the scope statement should also list what deliverables are excluded

from the project deliverables. For example, a project to create a new food product

may state that it is not including the packaging of the food product as part of the

project. Items and features not listed as part of the project deliverables should

be assumed to be excluded. Project exclusions Every project has boundaries. The scope statement defines the boundaries of the

project by defining what’s included and what’s excluded in the project scope. For

example, a project to create a piece of software may include the created compilation

of a master software image but exclude the packaging and delivery of the software

to each workstation within an organization. The project scope must clearly state what

will be excluded from the project so there’s no ambiguity as to what the stakeholders

will receive as part of the product.

Project exclusions Every project has boundaries. The scope statement defines the boundaries of the

project by defining what’s included and what’s excluded in the project scope. For

example, a project to create a piece of software may include the created compilation

of a master software image but exclude the packaging and delivery of the software

to each workstation within an organization. The project scope must clearly state what

will be excluded from the project so there’s no ambiguity as to what the stakeholders

will receive as part of the product. Project constraints A constraint is anything that restricts the project manager’s options. Common constraints

include predefined budgets and schedules. Constraints may also include resource limitations,

material availability, and contractual restrictions.

Project constraints A constraint is anything that restricts the project manager’s options. Common constraints

include predefined budgets and schedules. Constraints may also include resource limitations,

material availability, and contractual restrictions. Project assumptions An assumption is anything held to be true but not proven to be true. For example,

weather, travel delays, the availability of key resources, and access to facilities

can all be assumptions.

Project assumptions An assumption is anything held to be true but not proven to be true. For example,

weather, travel delays, the availability of key resources, and access to facilities

can all be assumptions.Obviously, the project scope statement is a hefty document that aims to create the

confines of the project and the expectations of the project manager, the project team,

and the project customers. It defines what’s in and what’s out of the project scope.

Overall, the project scope statement sets the tone of the project expectations and

paints a picture of what the project will create and how long and how much it’ll take

to get there.

When the project scope is created, several documents and information should be established

as early as possible in the project. Although this information is not included directly

in the project scope statement, it may be referenced as part of the support detail

every project needs.

Initial project organization The project team members, the project manager, and the key stakeholders are identified

and documented. The chain of command within the project is also documented.

Initial project organization The project team members, the project manager, and the key stakeholders are identified

and documented. The chain of command within the project is also documented. Initial defined risks The scope statement should document the known risks and what their expected probability

and impact on the project may be.

Initial defined risks The scope statement should document the known risks and what their expected probability

and impact on the project may be. Scheduled milestones The customer may have identified milestones within the project and assigned deadlines

using these milestones. The scope should thus identify these milestones, which are

essentially schedule constraints.

Scheduled milestones The customer may have identified milestones within the project and assigned deadlines

using these milestones. The scope should thus identify these milestones, which are

essentially schedule constraints. Fund limits Most projects have a limitation on available funding. This limit should be identified

in the project scope statement.

Fund limits Most projects have a limitation on available funding. This limit should be identified

in the project scope statement. Cost estimate Just as organizations have a limited amount of funds to invest in a project, they

have expectations for an estimate of what the project should cost to complete. This

estimate usually includes some modifier, such as +/−, a percentage, or a dollar amount.

Cost estimate Just as organizations have a limited amount of funds to invest in a project, they

have expectations for an estimate of what the project should cost to complete. This

estimate usually includes some modifier, such as +/−, a percentage, or a dollar amount. Project configuration management requirements No project manager wants a project to be overloaded with changes. This section

of the scope statement identifies the level of change control and configuration management

that can be expected within the project.

Project configuration management requirements No project manager wants a project to be overloaded with changes. This section

of the scope statement identifies the level of change control and configuration management

that can be expected within the project. Project approval requirements The approval requirements for project documentation, processes, work, and project

acceptance must be identified within the project scope statement.

Project approval requirements The approval requirements for project documentation, processes, work, and project

acceptance must be identified within the project scope statement.During the scope statement creation, the project manager may also face, believe it

or not, change requests from the project stakeholders. Change requests are managed

through the integrated change control process, which basically means that any proposed

change is reviewed and its impact on all areas of the project are considered. If a

change is approved, the scope statement should be updated to reflect the approved

change.

INSIDE THE EXAM

You’ll encounter three big themes from this chapter on the project exam: project scope

management, the WBS, and scope validation.

There are two types of scope: project scope and product scope. Unless the exam is

talking about features and characteristics of the project deliverables, it will be

referring to the project scope. If you think this through, it makes sense: Think of

all the billions of different product scopes that can exist—the exam will offer big

hints if it’s talking about product scope. Project scope focuses on the work that

has to be done in order to create the product. Recall that the project scope is concerned

with the work required—and only the work required—to complete the project.

Here’s a nifty hint: WBS templates come from previous projects and/or the project

management office, if the organization has one. WBS work packages are defined in the

WBS dictionary.

Scope validation is all about the project customer accepting the project deliverables.

Scope validation uses inspection as the tool to complete the process, which makes

perfect sense. After all, how else will the customer know if the deliverable meets

the project requirements unless they examine it?

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 5.04

Creating the Work Breakdown Structure

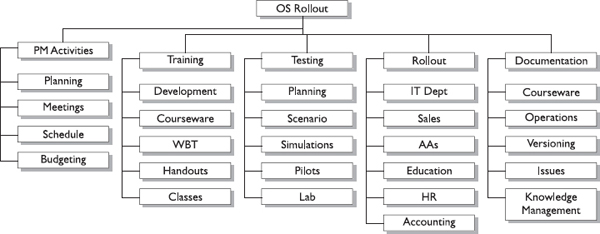

As you hopefully know by now, the WBS is a deliverables-orientated collection of project

components. Work that doesn’t fit into the WBS does not fit within the project. The

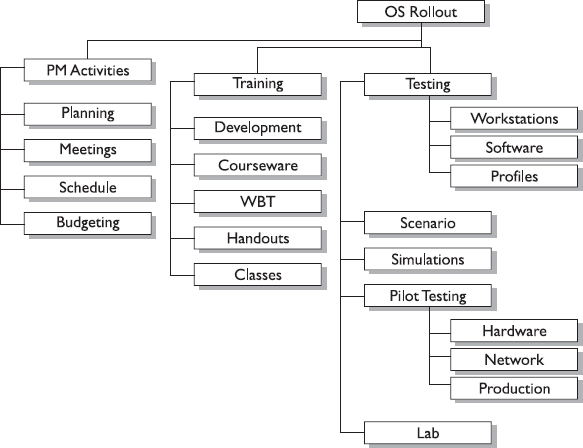

point of the WBS is to organize and define the project scope. As you can see in Figure 5-3, each level of the WBS becomes more detailed.

FIGURE 5-3 A sample structure for a technology project

The WBS is more than a shopping list of activities—it is a visual representation of

the high-level deliverables broken down into manageable components. A WBS is not a

chart of the activities required to complete the work—it is a breakdown of the deliverables.

The smallest element in the WBS is called the work package. The components in the WBS are typically mapped against a code of accounts, which

is a tool to number and identify the elements within the WBS. For example, a project

manager and a stakeholder could reference work package 7.3.2.1, and both would be

able to find the exact element in the WBS.

The components in the WBS should be included in a WBS dictionary, a reference tool

to explain the WBS components, the nature of the work package, the assigned resources,

and the time and billing estimates for each element. The WBS dictionary includes the

following:

Code of account identifier

Code of account identifier Description of each work package

Description of each work package Related assumptions and constraints

Related assumptions and constraints Related milestones

Related milestones Activities linked to each WBS dictionary entry

Activities linked to each WBS dictionary entry Responsible party for each entry

Responsible party for each entry Needed resources, time, and costs

Needed resources, time, and costs Quality metrics

Quality metrics References for technical specifications

References for technical specifications Acceptance criteria for each element

Acceptance criteria for each elementThe WBS also identifies the relationship between work packages. Finally, the WBS should

be updated to reflect changes to the project scope. The following are some essential

elements you must know about the WBS:

It serves as a major component of the project scope baseline.

It serves as a major component of the project scope baseline. It’s one of the most important project management tools.

It’s one of the most important project management tools. It serves as the foundation for planning, estimating, and project control.

It serves as the foundation for planning, estimating, and project control. It visualizes the entire project.

It visualizes the entire project. Work not included in the WBS is not part of the project.

Work not included in the WBS is not part of the project. It builds team consensus and project buy-in.

It builds team consensus and project buy-in. It serves as a control mechanism to keep the project on track.

It serves as a control mechanism to keep the project on track. It allows for accurate cost and time estimates.

It allows for accurate cost and time estimates. It serves as a deterrent to scope change.

It serves as a deterrent to scope change.As you can see, the WBS is pretty darn important. If you’re wondering where exactly

the WBS fits into the project as a whole, it is needed as part of the inputs for the

following seven processes:

Develop the project management plan.

Develop the project management plan. Define the project activities.

Define the project activities. Estimate the project costs.

Estimate the project costs. Determine the project budget.

Determine the project budget. Identify the project risks.

Identify the project risks. Perform qualitative risk analysis.

Perform qualitative risk analysis. Validate scope.

Validate scope.Using a Work Breakdown Structure Template

One of the tools you can use in scope definition is a WBS template. A WBS breaks down

work into a deliverables-orientated collection of manageable pieces (see Figure 5-4). It is not a list of activities necessary to complete the project.

FIGURE 5-4 This section of the WBS has been expanded to provide more detail.

A WBS template uses a similar project’s WBS as a guide for the current work. This

approach is recommended, since most projects in an organization are similar in their

project life cycles—and the approach can be adapted to fit a given project.

Depending on the organization and its structure, an entity may have a common WBS template

that all projects follow. The WBS template may have common activities included in

the form, a common lexicon for the project in the organization, and a standard approach

to the level of detail required for the project type.

Decomposing the Project Deliverables

Decomposition is the process of breaking down the major project deliverables into smaller, manageable

components. So what’s a manageable component? It’s a unit of the project deliverable

that can be assigned resources, measured, executed, and controlled. So, how does one

decompose the project deliverables? It’s done this way:

1. Identify the major deliverables of the project, including the project management

activities. A logical approach includes identifying the phases of the project life

cycle or the major deliverables of the project.

2. Determine whether adequate cost and time estimates can be applied to the lowest

level of the decomposed work. What is adequate is subjective to the demands of the

project work. Deliverables that won’t be realized until later portions of the project

may be difficult to decompose, since many variables exist between now and when the

deliverable is created. The smallest component of the WBS is the work package. A simple

heuristic of decomposition is the 8/80 rule: no work package smaller than 8 hours

and none larger than 80.

3. Identify the deliverable’s constituent components. This is a fancy way of asking

whether the project deliverable can be measured at this particular point of decomposition.

For example, the decomposition of a user manual may have the constituent components

of assembling the book, confirming that the book is complete, shrink-wrapping the

book, and shipping it to the customer. Each component of the work can be measured

and may take varying amounts of time to complete, but it all must be done to complete

the requirement.

4. Verify the decomposition. The lower-level items must be evaluated to ensure they

are complete and accurate. Each item within the decomposition must be clearly defined

and deliverable-orientated. Finally, each item should be decomposed to the point that

it can be scheduled, budgeted, and assigned to a resource.

5. Other approaches include breaking it out by geography or functional area, or even

breaking the work down by in-house and contracted work.

If your project team creates the deliverables at the lowest level of the WBS, the

work packages, then they’ve completed all of the required deliverables for the project.

In other words, the sum of the smallest elements equates to the entirety of the WBS

and nothing is forgotten. This is called the “100-percent rule.”

Updating the Scope Statement

The second output of scope definition is scope updates. During the decomposition of

the project deliverables, the project manager and the project team may discover elements

that were not included in the scope statement but should be. Or the project manager

and the team may discover superfluous activities in the scope statement that should

be removed. For whatever reason, when updating the scope statement, the appropriate

stakeholders must be notified of the change and given the justification for why the

change is being made.

Whenever a change enters the project that causes the project requirements to change,

you also have to change the project scope baseline. The project scope baseline comprises the project scope statement, the WBS, and the

WBS dictionary.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 5.05

Validating the Project Scope

Imagine a project to create a full-color, slick catalog for an electronics manufacturer.

The project manager has completed the initiation processes, moved through planning,

and is now executing the project work. The only trouble is that the project manager

and the experts on the project team aren’t sharing their work progress with the customer.

Plus, the work they’re completing isn’t in alignment with the product description

or the customer’s requirements.

The project team has created a trendy 1950s-style catalog with funky green and orange

colors, lots of beehive hairdo models, horn-rimmed glasses, and tongue-in-cheek jokes

about “the future” of electronics. The manufacturer wants to demonstrate a professional,

accessible, current look for its publications. What do you think will happen if the

project manager presents the catalog with his spin rather than following the request

of the customer?

Scope validation is the process of the project customer accepting the project deliverables.

Scope validation occurs at the end of each project phase or as major deliverables

are created. Scope validation ensures that the deliverables the project creates are

in alignment with the project scope. It is concerned with the acceptance of the work.

A related activity, quality control, is concerned with the correctness of the work.

Scope validation and quality control happen in tandem, as the quality of the work

contributes to scope validation. Poor quality will typically result in scope validation

failure.

You’ll be doing some scope validation when you pass the PMP examination. Your project

is to pass the exam, and once you do, you’ll have verified that you’ve completed your

project scope. Study smart, work hard, and keep after it. If you’ve made it this far,

you can go just a bit farther. You can do it!

You’ll be doing some scope validation when you pass the PMP examination. Your project

is to pass the exam, and once you do, you’ll have verified that you’ve completed your

project scope. Study smart, work hard, and keep after it. If you’ve made it this far,

you can go just a bit farther. You can do it!Should a project get cancelled before it has completed the scope, scope validation

is measured against the deliverables up to the point of the project’s cancellation.

In other words, scope validation measures the completeness of the work up to cancellation,

not the work that was to be completed after project termination.

Examining the Inputs to Scope Validation

To validate the project scope, which is accomplished through inspection, there must

be something to inspect—namely, work results. The work results are compared against

the project plan to check for their completeness and against the quality control measure

to check the correctness of the work.

One of the biggest inputs of scope validation is the requirements documentation you

created as part of the collect requirements process. This information describes the

requirements and expectations of the product, its features, and attributes. The product

documentation may go by many different names, depending on the industry:

Plans

Plans Specifications

Specifications Technical documentation

Technical documentation Drawings

Drawings Blueprints

BlueprintsThe project manager will also rely on the project management plan, the scope baseline,

the requirement documentation, and the traceability matrix to help compare what was

promised to the customer and what was actually created. Work performance data such

as nonconformance, degree of accuracy, and other performance metrics are also needed

to see how well the deliverable conform the criteria for acceptance by the project

customer.

Inspecting the Project Work

To complete scope validation, the work must be inspected. This may require measuring,

examining, and testing the product to prove it meets customer requirements. Inspection

usually involves the project manager and the customer inspecting the project work

for validation, which in turn results in acceptance. Depending on the industry, inspections

may also be known as the following:

Reviews

Reviews Product reviews

Product reviews Audits

Audits Walkthroughs

WalkthroughsFormally Accepting the Project Deliverables

Assuming the scope has been verified, the customer accepts the deliverable. This is

a formal process that requires signed documentation of the acceptance by the sponsor

or customer. Scope validation can also happen at the end of each project phase or

at major deliverables within the project. In these instances, scope validation may

be conditional, based on the work results. When the scope is not verified, the project

may undergo one of several actions: It may be cancelled and deemed a failure, sent

through corrective actions, or put on hold while a decision is made based on the project

or phase results.

If a project scope has been completed, the project is complete. Resist the urge to

do additional work once the project scope has been fulfilled. Also, be cautious of

instances in which the scope is fulfilled and the product description is exact, but

the customer is not happy with the product. Technically, for the exam, the project

is complete even if the customer is not happy.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 5.06

Controlling the Project Scope

When it comes to project management, the one constant thing is change. Changes happen,

or try to happen, all the time in projects. The project manager must have a reliable

system to track, monitor, manage, and review changes to the project scope. Change

control focuses on three things:

It facilitates scope changes to determine that changes are agreed upon.

It facilitates scope changes to determine that changes are agreed upon. It determines whether a scope change has happened.

It determines whether a scope change has happened. It manages the scope changes when, and if, they happen.

It manages the scope changes when, and if, they happen.Examining the Inputs to Scope Change Control

Throughout a project’s life, the need and desire for change will come from project

team members, the sponsor, management, customers, and other stakeholders. All of these

change requests must be coupled with supporting evidence to determine the need of

the change; the change’s impact on the project scope (and usually on other processes

as well); and the required planning, schedule, and budget to account for the changes.

See the video “Managing Scope Changes.”

See the video “Managing Scope Changes.”Using the Project Management Plan

The project management plan does offer some specific direction on how changes are

allowed into the project. Although most project managers are resistant to change once

the scope has been created and agreed upon, changes are sometimes valid. You’ll rely

on the change management plan as a general direction of the flow of decisions to determine

whether a change is valid for your project. This assumes, of course, that you, the

project manager, have control over change management decisions.

You’ll also rely on the configuration management plan to determine how change is allowed

specifically to the project scope. Configuration management is the control and documentation

of the features and functions of the project’s product. It’s important for you to

communicate the impact of change on the product to all of the stakeholders as part

of the change control review.

Finally, you’ll rely on your favorite project management tool, the scope baseline.

The scope baseline represents the sum of the components and ultimately the project

work that make up the project scope. The change requests may be for additional components

in the project deliverables, changes to product attributes, or changes to different

procedures to create the product. The WBS and WBS dictionary are referenced to determine

which work packages would be affected by the change and which may be added or removed

as a result of the change.

Relying on the Scope Management Plan

Remember this plan mentioned earlier in the chapter? It’s an output of scope planning

and controls how the project scope can be changed. The scope management plan also

defines the likelihood of the scope to change, how often the scope may change, and

how much it may change. You don’t have to be a mind reader to determine how often

the project scope may change and by how much; you just have to rely on your level

of confidence in the scope, the variables within the project, and the conditions under

which the project must operate. The scope management plan also details the process

of how changes to the project scope will be documented and classified throughout the

project life cycle.

Referencing the Requirements Documentation

The requirements management plan, the requirements traceability matrix, and the actual

requirements documentation are inputs to the control scope process. You’ll use the

requirements management plan as it defines how changes to the requirements are allowed

and how they’re to be managed. The actual requirements documentation is also needed,

because these are the specific elements that the scope change may be affecting. You’ll

use the requirements traceability matrix to see how a change in the requirements may

directly affect other requirements in the project.

Considering Change Requests

Some project managers despise change requests. Change requests can mean additional

work, adjustments to the project, or a reduction in scope. They mean additional planning

for the project manager and time for consideration, and they can be seen as a distraction

from the project execution and control. Change requests can address preventive actions,

corrective actions, defect repair, or scope enhancements. Change requests are an expected

part of project management.

Why do change requests happen? Which ones are most likely to be approved? Most change

requests are a result of the following:

Value-added The change will reduce costs (often due to technological advances since the time

the project scope was created).

Value-added The change will reduce costs (often due to technological advances since the time

the project scope was created). External events These could be such things as new laws or industry requirements.

External events These could be such things as new laws or industry requirements.

Change requests are more than just changes to the project scope. They include preventive

action, corrective action, and defect repairs.

Errors or omissions Ever hear this one: “Oops! We forgot to include this feature in the product description

and WBS!” Errors and omissions can happen to both the project scope (the work to complete

the project) and the product scope and typically constitute an overlooked feature

or requirement.

Errors or omissions Ever hear this one: “Oops! We forgot to include this feature in the product description

and WBS!” Errors and omissions can happen to both the project scope (the work to complete

the project) and the product scope and typically constitute an overlooked feature

or requirement. Risk response A risk has been identified and changes to the scope are needed to mitigate the

risk.

Risk response A risk has been identified and changes to the scope are needed to mitigate the

risk.Implementing a Change Control System

The most prominent tool applied with scope change control is the change control system.

Because changes are likely to happen within any project, there must be a way to process,

document, and manage the changes. The change control system is the answer. This system

includes the following:

Cataloging the documented requests and paperwork

Cataloging the documented requests and paperwork Tracking the requests through the system

Tracking the requests through the system Determining the required approval levels for varying changes

Determining the required approval levels for varying changes Supporting the integrated change control policies of the project

Supporting the integrated change control policies of the project When the project is performed through a contractual relationship, the scope change

control system must map to the requirements of the contract

When the project is performed through a contractual relationship, the scope change

control system must map to the requirements of the contract

The PMBOK Guide lists only one tool and technique for controlling the project scope: variance analysis.

This is really a broad approach to controlling the scope, because variance analysis

addresses the difference between the planned scope baseline and what was actually

experienced. Corrective or preventive actions may be needed to correct project variances.

Revisiting Performance Measurement

Performance reports are inputs to scope change control—the contents of these reports,

the actual measurements of the project, are evaluated to determine what the needed

changes may be. The reports are not meant to expose variances as much as they’re meant

to drive root-cause analyses of the variances. Project variances happen for a reason:

the correct actions required to eliminate the variances may require changes to the

project scope.

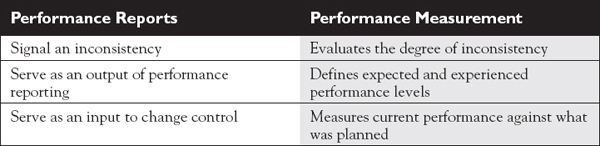

There is a distinct difference between performance reports and performance measurement,

as shown in Table 5-1.

TABLE 5-1 Performance Reports vs. Performance Measurement

Completing Additional Planning

Planning is iterative. As change requests are presented, evidence of change exists,

or corrective actions are needed within the project, the project manager and the project

team will need to revisit the planning processes. Change within the project may require

alternative identification, study of the change impact, analysis of risks introduced