3

Did it work?

Yes and no. I was spoiled and pampered every day by three adoring women who allowed me to indulge my interests and excused my moods. I played Little League baseball and basketball, and my mother also signed me up for tennis lessons at the Cosmopolitan Club in Harlem. Fred Johnson was my teacher, the same one-armed pro who taught tennis champion Althea Gibson.

Friends of mine always said I was different. They never explained why or how or what they meant. They simply said, “Billy, you’re different.”

I never got the memo about conforming or pretending to be something other than who I was—quiet, shy, thoughtful, and content to dream. I played with dolls and made up stories for them. I was inspired by a character I saw Alan Ladd play, a guy searching for himself after returning from the war, and I was a kid who was kind of internal, and, not surprisingly, so were my dolls.

I was also obsessed with gangster movies. I staggered across the kitchen like Jimmy Cagney after he was shot in Public Enemy, and I imitated Edward G. Robinson in Little Caesar when he said, “Mother of mercy, is this the end of Rico?”

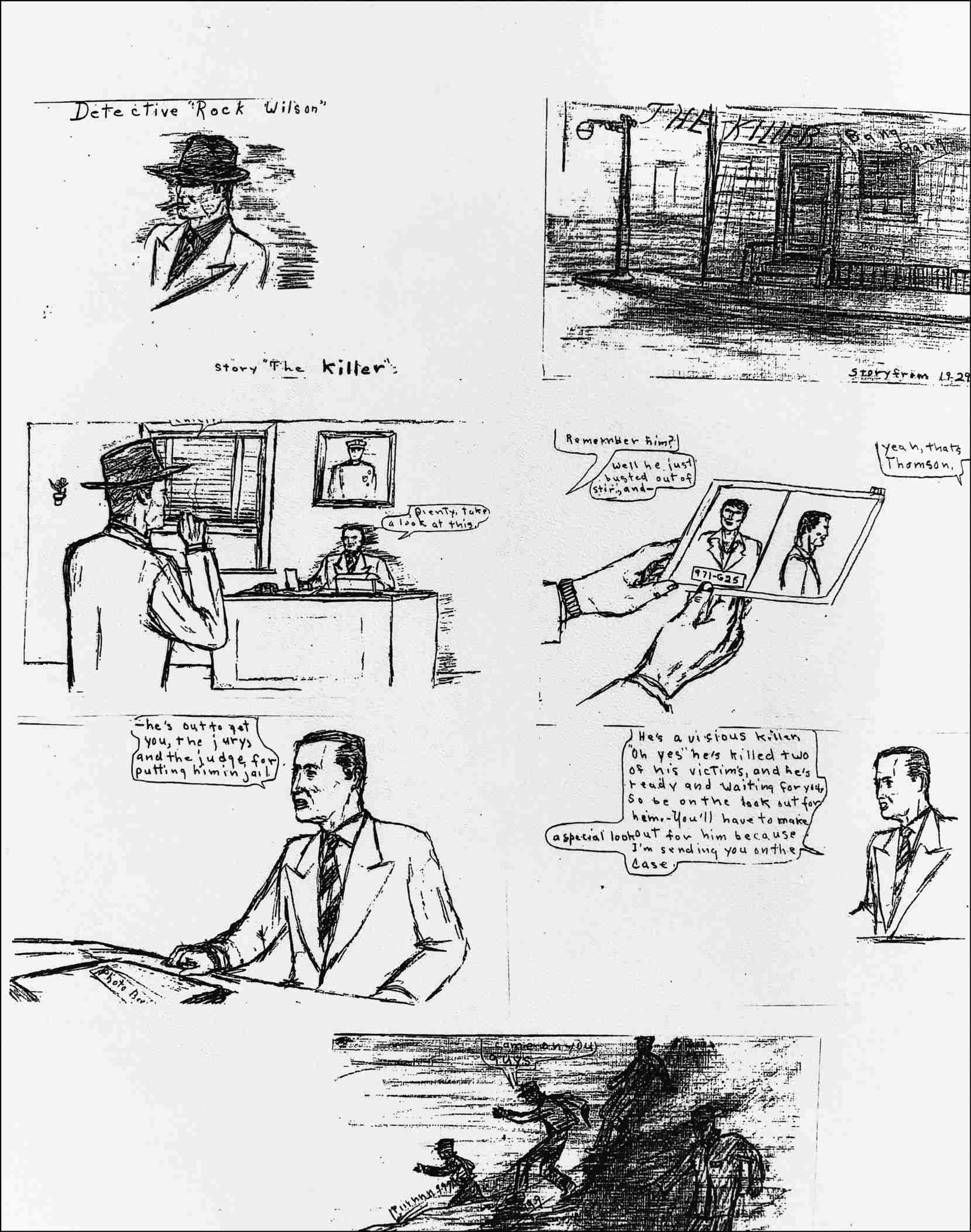

I had a natural ability to draw when I put pen to paper, and I used it to create comic books, featuring G-men and robbers like I saw in the movies. Alan Thomas, my friend and business partner at P.S. 113, sold them for ten cents. We split the money fifty-fifty. That is, until my mother found out what we were doing and shut down our fledgling enterprise. “Sonny, you have more important things to do,” she said. “Like homework!”

A page from a comic book I drew at age six

My mother emphasized education and made sure that Lady and I got into the best public schools in our area. She used a cousin’s address to enroll us in P.S. 113, and she did the same with my aunt Amy’s address so we could attend Booker T. Washington Junior High. Lady was far more studious and academically inclined than me. She was a straight-A student from the time she entered a classroom through her graduation from NYU. I managed solid B’s. I was bored sitting in class. My mind took flight, drifting out the window and on to other things I found more interesting than listening to the teacher.

My father once lost his temper with me and called me stupid, something that scarred me forever. I never could shake that. Daddy thinks I’m stupid?

“No, no, no, you’re not stupid,” my sister said. “You’re very smart. It’s just your head is always in the clouds.”

I would sit in class and wonder why I had to arrive at the same answer as everyone else. Why couldn’t there be a different answer? Why couldn’t I find my own way there? Why couldn’t I read something else? Why couldn’t I be something else? My friend Reggie, a stimulating abstract thinker, wanted to become a pro basketball player; another friend, Donald, set his sights on becoming a preacher; and other friends wanted to become scientists, teachers, and doctors. These little dark-skinned boys were brilliant. When it was my turn to share my hopes and dreams, I shrugged and said I didn’t know what I wanted to be, which wasn’t true. I just didn’t want to get laughed at.

The truth was, I wanted to be a swashbuckling hero like Douglas Fairbanks Sr. and Errol Flynn in the movies that my mother loved. I also wanted to be like Melvyn Douglas, Fred Astaire, and Humphrey Bogart in To Have and Have Not—a suave romantic. I wanted to save the day and sweep women off their feet. But how was I supposed to explain that without being ridiculed?

I found a kindred spirit in my building. His name was Dickie Stroud. I was a kid when his family moved into our building. I looked down from the fire escape one day and saw him on the sidewalk playing with a cap pistol, and I had to meet him. He lived on the sixth floor, one above us. He was five years older than me. By the time I was a teenager, though, we were best friends.

Dickie was an artist, an athlete, and an avid reader. It led him in all sorts of interesting directions. As an adult, he became the founding sensei of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Aikido Club. One day he shoved a book into my hands and told me it was the best book he’d ever read. I looked at the title: The Little Prince.

“It’s French,” he said. “By Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.”

“It sounds like a kid’s book,” I said.

“It’s not. Read it.”

The book captured my imagination and opened my eyes to new ideas. That was the basis of our friendship: curiosity. I showed him my drawings and shared my fascination with the movies. He listened intently and without making fun of me when I gave him a passionate review of Moira Shearer’s beauty and Anton Walbrook’s style after seeing The Red Shoes with my mother. After I went to the ballet with my mother, he asked questions about it, coming from a place of genuine interest; and when I mentioned liking opera, he started listening to it, too. Picture two dark-skinned teenage boys in Harlem cracking each other up by singing, “Fee-gar-o! Fee-gar-o!” We were learning.

At thirteen, I got a job as a bonded messenger for the jewelry store where my mother worked. I dropped jewelry off at their stores in the different boroughs. I liked earning my own money, and the next year Dickie and I pooled our savings and bought some secondhand barbells and weights, which we set up on the roof of our building. Under his tutelage I built up my scrawny frame, and after workouts, the two of us would stand on the sidewalk and flex for the neighborhood girls who came around to talk to us.

When the weather warmed up, we rowed on the lake in the park—for exercise, of course. But we didn’t mind if our female admirers stopped by to watch us.

Girls changed everything. I accompanied my sister to a party thrown by a friend of hers. At one point in the evening, I was sitting by myself in a room where all the kids were putting their coats after they got to her house when a pretty girl my same age walked in. We started to talk. I felt an attraction to her. Though I was normally shy and quiet, our conversation grew intimate, with me doing most of the talking and her listening. I told her how she made me feel, and especially how I imagined myself making her feel.

There was something sweet and special about the moment. I was trying to be seductive and romantic, and she was a willing participant. I remember she looked at me with the most relaxed expression on her face and smiled faintly before shutting her eyes, which I took as an invitation to continue. In a soft, sensual voice, I let her know how much I appreciated her beauty, and I described the ways I imagined showing that to her.

A few moments later, she had an orgasm. She was a little bit embarrassed afterward, but not that much, and I felt like I had discovered a new superpower, which I suppose I had. It was called romance—and I was eager to try it again.

Throughout junior high, both Lady and I were recognized for our artwork. It was singled out in class, put up in the school’s halls, and highlighted in seasonal shows. But art was only one of the many things my sister excelled in. For me, it was everything, a way of expressing myself and standing out the way other kids did in math, science, or language. I could draw. I could paint. I could illustrate an idea, sketch a friend throwing a football, or hand the prettiest girl in my class a portrait I drew of her.

Before we graduated, the school’s art teacher, Mrs. Schitzer, invited my family to her house for dinner. The epitome of a teacher who cared and inspired and changed lives, she was an enthusiastic advocate of our work, and she wanted to talk with my parents about Lady’s and my future. Explaining that both of us were exceptionally talented, she urged my mother to send us to New York’s prestigious High School of Music and Art. Decades later, Music and Art merged with the dance-oriented High School of Performing Arts and inspired the movie and television series Fame.

Not everyone could get into Music and Art, Mrs. Schitzer explained. It was like Bronx Science—exclusive. You had to be gifted in one of the arts—music, acting, drawing. With my parents’ blessing, Mrs. Schitzer helped us submit our applications, along with the required samples of our artwork, and soon thereafter, Lady and I received formal notification in the mail. We were accepted.

Located at West 135th Street, in Harlem’s Hamilton Heights neighborhood, Music and Art was in a large building on the City College of New York campus. The building was known as “the castle on the hill,” and you had to climb a very steep staircase to get to it. Though it was part of the New York City public school system, Music and Art was run like a private school, and as I walked through the front door the first time in the fall of 1952, I knew this was the right place for me.

Everyone had a talent, and just like in the movie and TV series that would come later, students would break into song and dance in the hallways and classrooms, preening and discussing what was happening in Hollywood, on Broadway, and in music as if we were already part of that community, which I suppose we were. My work stood out among the artists. I absorbed the instruction without having to work too hard, but I worked hard at it nevertheless, seriously motivated to be good and get better.

To my dismay, though, academics were still at the core of the curriculum. I lacked interest in most subjects, and I was simply terrible in math. The deeper we got into the book, the more I turned my head toward the window and let my thoughts drift outside. My homework piled up. One day the teacher told me to stay after class. She was known to be brusque and stern, so I expected the worst.

“Billy, you’re struggling,” she said.

I looked down at my desk.

“Yes, I’m sorry,” I said.

“But you’re trying, right?”

“Yes, I am.”

She took a step closer and sat on the desk next to mine.

“I’ll make you a deal,” she said. “If you do your work on time, I will be as helpful and as patient as necessary.”

“I will,” I said.

She got up and returned to her desk at the front of the classroom. I was free to gather my books and go. She smiled at me as I walked toward the door. She recognized that I needed a teacher who would take her time, and she wanted me to know she was that teacher. I thanked her.

“But Billy,” she said, stopping me as I reached for the door handle, “we have to get through algebra.”

“I understand,” I said.

“This year.”

On April 6, 1953, my sister and I turned sixteen. We celebrated with a party whose planning occupied my mother, grandmother, and sister for months. The weeks leading up to it were consumed with details about food, clothes, music, flowers, invitations, and RSVPs. Did we hear from Lady’s good friend Camilla? Were her parents, Dr. and Mrs. Jones, coming? We had catered food, a live band, and fresh flowers. Everyone wore tuxedos and formals. After we blew out the candles, Lady and I were presented with twin diamond rings. Then the hall filled with applause.

The guest list included all the Sugar Hill kids, the Black bourgeoisie of Harlem. My sister belonged to the Jack and Jills and the Continental Society, the premier social clubs of the day, and this party served notice that Lady and I were part of this upper echelon of Black society.

My glamorous twin sister, Lady—a gorgeous lady, indeed—in 1960

The Jack and Jill Club and the Continental Society were started and run by women who wanted to provide their children with a path to success that wasn’t available to them and the generations that preceded them. The kids in these organizations were high achievers, future doctors, lawyers, professors, and scientists. We met each other as teens, and by our twenties, we were supposed to be the cream of marriage material.

I was never as serious about these clubs and their social events as my sister (and my mother). I went to the dances and the parties, but I would sit in the corner, wearing an old sport coat with frayed lapels and tattered sleeves, and brood, giving the impression that I was a rebel preoccupied with more serious thoughts than dancing. Like Marlon Brando in The Wild One.

What was I rebelling against?

Whaddya got?

Except I was a good kid.

At school, I was friendly with Peter Yarrow, who later became one-third of the singing group Peter, Paul & Mary. He studied painting, but I recall him as an intellect with enviable skills in math. He signed my yearbook, “Good luck, Brando.”

My best friend at Music and Art was a girl my age named Ruth Herschaft. A serious and talented artist, she had dark hair, large, brown eyes that seemed to take in the entire world, and a fun, sassy sense of humor. We walked together between classes. One day she said, “You know, Billy, you have a great tush.”

“Tush?” I said. “What’s that?”

I’d never heard that word before.

“It means rear end,” she said. “You’ve got a cute rear end.”

Though we weren’t romantically involved, Ruthie invited me to her family’s home for dinner. She wanted me to meet her parents. I was sure she had told them about me, her Black friend, which had to be a novel thing for Jewish families like hers in Riverdale, a predominantly Jewish suburb on the Hudson River just south of Yonkers.

I took the bus there and arrived with a bouquet of flowers for her mother. I was warmly welcomed inside their apartment, though Ruthie’s mother seemed nervous to meet me. I think Ruthie enjoyed that; I was amused myself. Then the two of them disappeared into the kitchen, leaving me alone with Ruthie’s father. He might have thought his daughter had gone astray by hanging out with this Black young man, but if he did, I couldn’t tell.

He was cool and friendly as we sat in their living room and talked. Both of us pretended not to hear Ruthie and her mother talking about me in the kitchen, especially when we heard Ruthie’s mother very clearly say, “I thought you said he looked like Harry Belafonte. He doesn’t look at all like Harry Belafonte.” Before dinner, her father said a traditional blessing over Shabbat candles he lit to welcome the Sabbath, and then it was time to eat what Ruthie’s mother called “good Jewish cooking.”

Our differences were embraced and explored. By dessert, they knew all about my life in Harlem, the neighborhood, my family’s history, and my thoughts about art, books, and the movies. I learned about them, too. We ate, talked, laughed, and found things in common—how so much of our lives were about family. The only thing that could have made the night any better was if I had looked like Harry.

On my way out of the building, I was stopped by a couple who lived on the floor below Ruthie’s family. A door opened, and there stood an older Jewish couple. They had been listening for someone coming down the stairs. If they were surprised to see a Black teenager in their building, though, they didn’t show it. I smiled and said hello, quickly explaining that I was friends with Ruthie from school. They asked if I could follow them inside their apartment and turn off several lights, something they said they couldn’t do after dark on Friday nights as observant Jews. “Thank you,” the older lady said. Her husband shook my hand. “You’re a nice young man,” he said. “You tell your parents they raised a nice young man.”