5

As my second year at the National Academy got underway, I was more confident and sensed I was starting to produce real art, as opposed to the pretty pictures in my class on figurative drawing. The change was due not only to how I was painting but what I was painting in class: nudes.

The class was called Life Study, drawing and painting from real life, and it was art school in the classic sense. Every day we drew from nude models, learning the techniques and secrets of the old masters and studiously working to perfect them as if it was nothing out of the ordinary to spend a few hours looking at a human being sitting in front of us without any clothes. Outwardly, I appeared to take this in stride, but privately I couldn’t believe this was school. After a week or two, I calmed down, and staring at the models did become normal.

Actually, it became a wholly different experience. How I looked at these models—these people, these human beings—changed and evolved into something deeper, more thoughtful. I moved past seeing their breasts and hips in a sexual way, to seeing them as parts that gave shape to overall femininity. Each of their bodies had a wonderfully imperfect symmetry, and a uniqueness, that entranced me.

Each model was a mystery to be solved. What did I see in front of me? What didn’t I see that was in front of me? This was where the learning happened and also the opportunity to produce art. When a model removed their clothes, they weren’t just exposing their bodies. They were revealing their vulnerability and humanity; the sacred part inside that their body protected, and what I had to do as an artist, if I was going to call myself an artist, was to see that in them, and in myself, and then put that in my art.

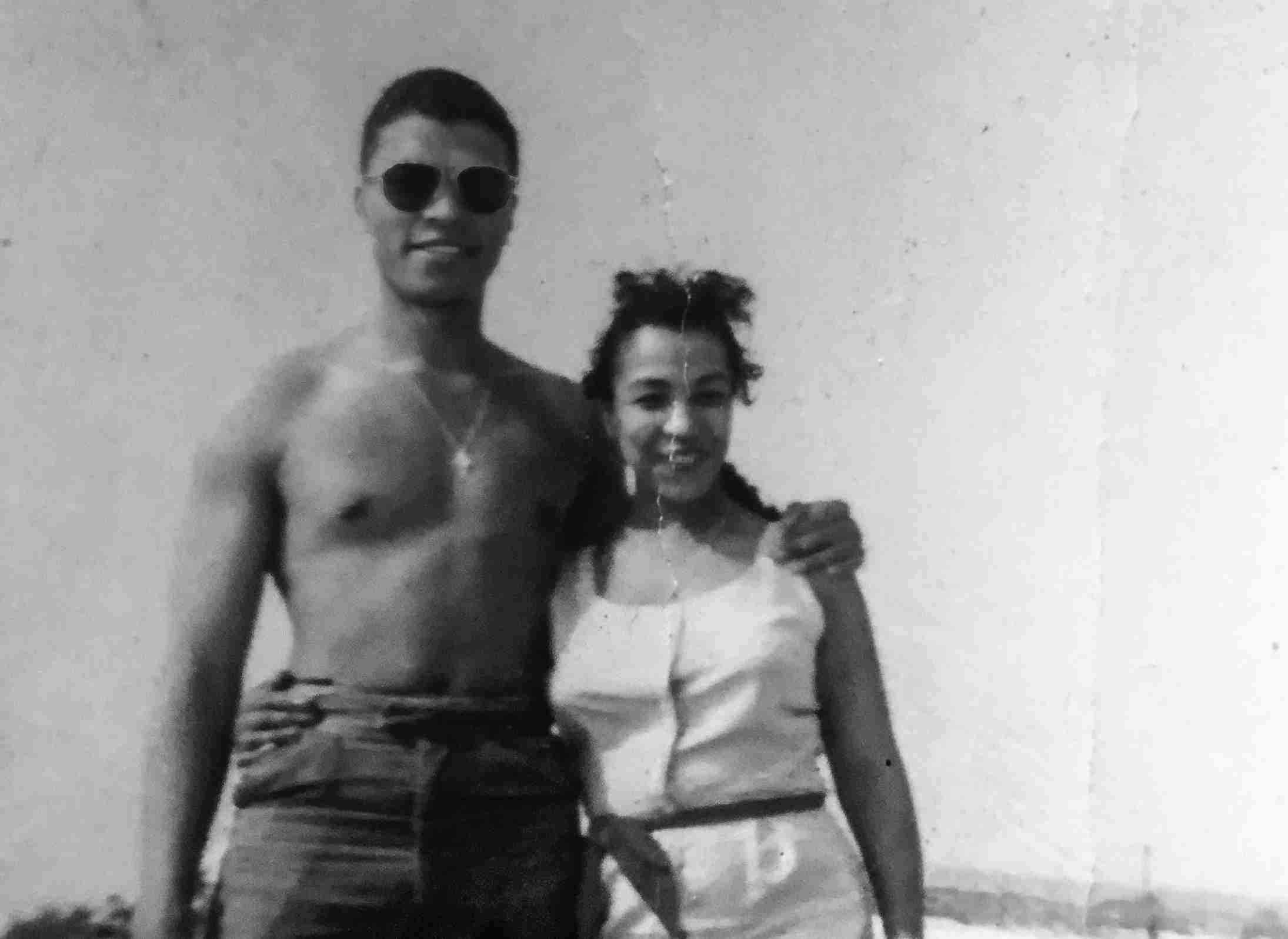

My mother and me at Jones Beach in 1955

And that’s what I painted—or tried to—the many colors, shapes, and forms of humanity. The poetry and mystery of us. There was the physical shape. There was also the spirit inside the shape. It was all about tones and shades, as was life itself. It wasn’t just Black or White, as people were typically defined. That was merely the starting point and far too limiting once you really looked at people, studied them, and tried to figure out what was inside them. If you went no further, you would miss all the nuances of being human.

That was the magic of this class: It opened me to seeing more in other people. I tried to see their potential, emotion, originality, and uniqueness. I tried to see their lives, their relationships, their frustrations and passions. What was behind their expression? It also opened me up to myself. As I thought about them, my mind would wander, and I would also see the complex mix of history and blood that was in my own family. I saw the full spectrum of colors. Gradually, I realized that I wasn’t just painting the model in front of me; I was painting what I thought the model felt, but also what the model made me feel.

This class was truly life study, not just drawing and painting from models but a way to walk outside into the world and engage with others. The human anatomy became something I began to see and think about as a cosmic experience, like looking at the stars and the planets. Seeing people as forms and shapes and gradations containing a spectrum of the feelings, thoughts, and experiences that made them. The body was something temporal. It exists and then it doesn’t exist anymore. But inside is something spiritual, soulful, and timeless. Of another dimension. An energy that remains as we come and go. It’s who we really are, our better selves, our best selves, our essence.

Could I really paint this? I tried and who knows, maybe I pulled it off, or got close. I was nominated for a Guggenheim Award that year. So I must have done something right.

For a few months, I did some nude modeling myself, at the Art Students League and Parsons School of Design. I made six dollars per class, pretty good money then. But holding the same pose for two to three hours was more than I could bear. You might not think it so, but it was incredibly hard and painful. My entire body ached and cried out to change positions, to get up and do something else. Holding still like that was unnatural. Try to keep the same pose for even just ten minutes. It’s hard. We’re designed for movement.

I made better money and put my training to use as a part-time fashion illustrator for a Manhattan advertising firm, though that job also had its drawbacks. For instance, a long commute back and forth, and actual office hours. One day as I was taking the subway to work, a crazy idea popped into my head: extra work as an actor.

I don’t know where the idea came from. I overheard someone at school say they were doing it. At the time, television dramas were broadcast live from New York City. I thought it might be easy money if I could get the work. Easier than riding the subway downtown, drawing dresses, blouses, and shoes, and then catching the subway back uptown at night. And I would have my freedom back. No set hours. I could paint and wander as I wished.

I knew it was a good idea, but I didn’t know how to get started, and so I let it go until a very chilly winter day at the end of 1956 when I was walking somewhere and ducked into a men’s clothing store to get warm. As I did so, I literally ran into a guy coming out of the store, nearly knocking both of us down.

After I apologized, we introduced ourselves and began talking. His name was Liam Dunn, and he was on the staff at CBS television over on 57th Street and, as luck would have it, was the network’s casting director. I explained that I was a full-time art student at the Academy but interested in working as an extra on television shows. He gave me his card and told me to make an appointment to see him at his office.

“Remind my assistant that we bumped into each other in the clothing store,” he said.

“I will,” I said.

It’s impossible to say whether I have an acting career because of Liam, but I do know that he took my call a few days later and my career in front of the camera began because of this friendly man who chain-smoked cigarettes and laughed easily. I later found out he also gave Warren Beatty and Steve McQueen their first acting jobs on TV. He placed me on the Sergeant Bilko Show, starring Phil Silvers; and more extra work quickly followed. The acting work went so well, in fact, that I soon had a dilemma: whether to pursue art or acting.

Both appealed to me, and I truly didn’t know which one to choose. Then one night I saw Thelonious Monk in concert at Randall’s Island. Seeing the jazz great live in concert was unforgettable. He played phrases, chords, and notes that were unique and unexpected, the music that he heard in his mind, a realm that was all his own, and as I sat and listened, that seemed to be what I had to do, to find the music in me, the music that was mine. But Monk was fearless. At one point during the performance, he stopped playing, walked over to one of his musicians who wasn’t quite getting there, and explained what he wanted to hear. Then he started the tune all over again.

A few days later, I was describing the concert to Dickie. We were in our studio, and I was relating the way Monk had stopped and started that song to the debate I was having with myself over painting versus acting. I said something like if acting doesn’t work out, I can start over again, to which Dickie replied, “You’re already acting, and the money is pretty good.” He was right. I guess my decision had already been made. Either I had found the music, or the music had found me. I was going to act.

Somehow word of this reached the Academy’s director, George Porter. He telephoned my mother to express his disappointment and ask her to talk me out of it. “Don’t let Billy become an actor,” he implored. “He’s a painter.” My mother relayed that conversation to me and asked, “Are you sure?” I can’t say that I’ve ever been sure about anything, but I did think it was remarkable that the Academy’s director saw me as a promising part of the art world. I had always painted with the conviction that I would become one of the greatest painters the country had produced.

But in what would become one of the recurring stories of my life, when I wanted to go right, the universe had a way of sending me to the left.

Dickie and I and his friend Leon and one of Leon’s friends—the two of them were also friendly with Sidney Poitier—were always talking about art and theater and different things related to those worlds, and when I said I wanted to sign up for acting classes, Dickie joined me. We worked with Mildred Gillendre; I also took classes with Herbert Berghof and Paul Mann, who complimented me for having talent and being “a good-looking kid.” There was no debate anymore. I was an actor.

I tried to get into The Actors Studio, the elite acting school founded by director Elia Kazan and run by Lee Strasberg, but I was turned down, twice. I still participated in a couple projects there, including one with the brilliant theater designer Mordecai Gorelik. Ultimately, though, acting class wasn’t for me. I wanted to work.

The exception was a workshop I took with Sidney Poitier. He was a few years away from winning his first Academy Award for Lilies of the Field, but he was already famous and immensely respected for his work in Blackboard Jungle, Edge of the City, and his performance as a young Black doctor treating a white bigot in No Way Out. His rise from extreme poverty to actor was well known to people, especially the community of Black actors in New York.

Dickie’s friend Leon had told us that Sidney was going to teach an acting class in Harlem. We signed up immediately. Classes were held in a loft on 125th Street and Eighth Avenue. It was a remarkable time to catch Sidney. He was still very much an actor, a serious actor, not yet a celebrity or personality, and he was on fire. So taking a class from him was an opportunity to be with the person who was changing the game.

Brando was probably my favorite actor at the time, the one I watched most carefully, because…well, because he was Brando. He brooded, and so did I. But I also appreciated the versatility of Juano Hernández, Frank Silvera, and Canada Lee, unsung and underappreciated actors whose ability to take on any type of role appealed to my sense of what it meant to be an actor. They knew life and played all types of characters regardless of skin color or ethnicity.

Then Sidney entered the picture. He stood apart from everyone who came before him. He introduced a whole new school of acting that I had not seen in other Black actors. He was modern, current, the way Brando had been modern and current—only Sidney was one of us. He was part of my lexicon. The way he acted, it felt like he was internalizing more than was written, which was the same direction I was going in as an actor.

Everyone in Sidney’s class performed a scene from a play of their choice, and afterward, Sidney led a discussion about our choices. I performed the explosive rape scene in A Streetcar Named Desire, in which Stanley comes home and is alone with Blanche after leaving Stella in the hospital. Both Stanley and Blanche have been drinking. It was risky, in that everyone had seen Brando and Vivian Leigh in the movie, and a false or inconsistent or even imitative note would stand out. I partnered with Janet MacLachlan, a young actress also beginning what would be a long career. She was excellent.

When we finished the scene, there was an uneasy stillness in the room while Janet and I caught our breath, and Sidney let it stay that way for a moment or two before giving his assessment. “I like the direction you took,” he said. Later, I heard he thought I had the talent to go someplace. Sidney was an interesting teacher and, most importantly, an inspiration. He gave us a sense of ourselves and the possibility of fitting into the mainstream.

Frank Sinatra’s nephew joined a touch football game I was playing with friends one day in Central Park. Someone mentioned that he was an actor, and I asked him for advice. He suggested I call Diana Hunt, a woman who ran her own small agency and was agreeable to taking on new talent.

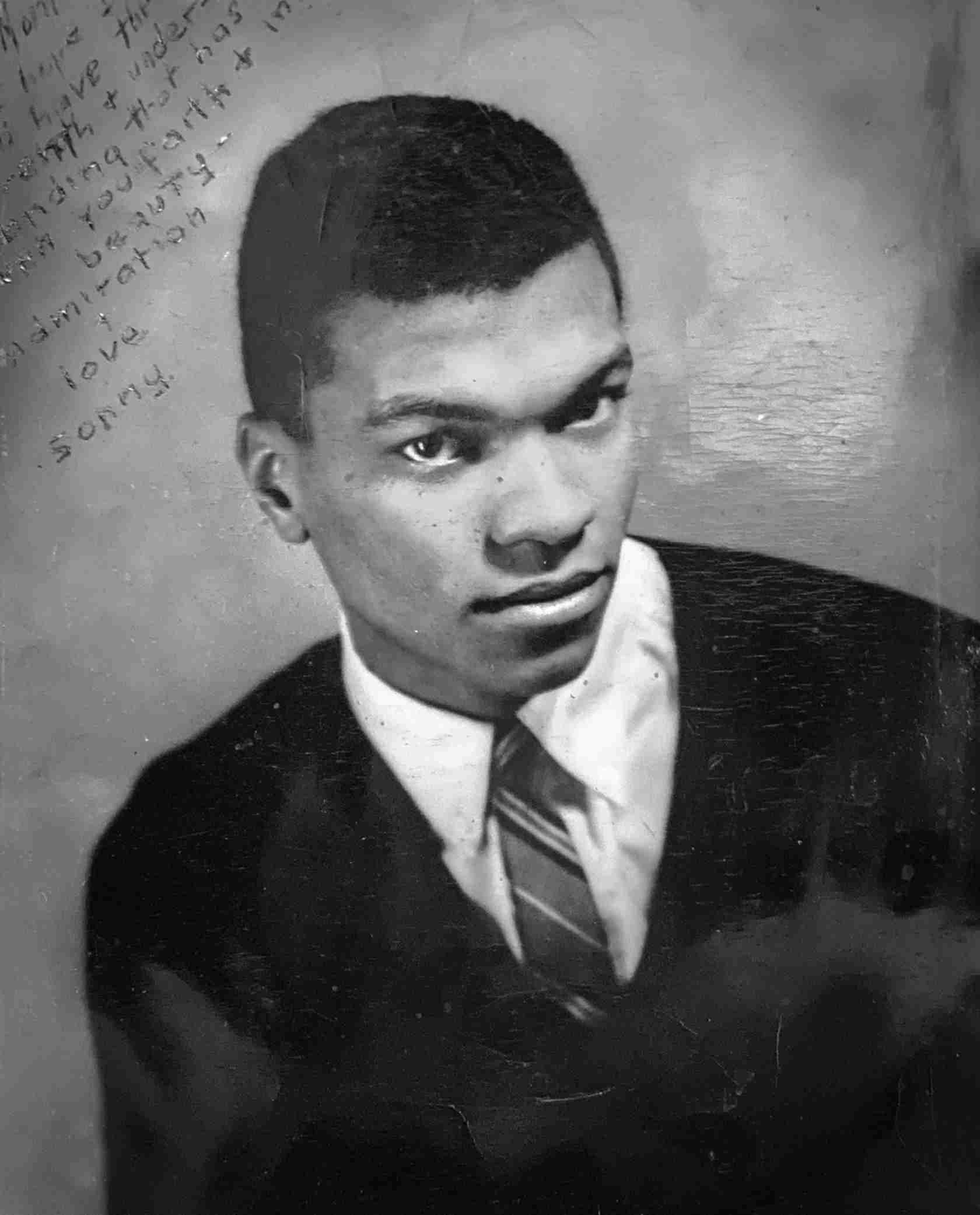

My headshot, which I inscribed to my mom and signed “Love Sonny,” at age twenty-three

Diana had a small agency on 44th Street between Broadway and Eighth, in the same building, and on the same floor, where producer David Merrick had his offices. It was something she pointed out when we first met, as if her proximity to someone of his stature gave her an advantage that others didn’t have, which, as I would come to see, was true. We had a good talk, and she agreed to take me on. “You’re handsome,” she said. “You’re good on the eyes. But I can tell there’s more to you than looks. I like you.”

Now, with both Diana and my friend at CBS, Liam Dunn, looking out for me, it didn’t take long for me to find work, starting with a small role on the Hallmark Hall of Fame drama The Green Pastures. Though uncredited, it gave me something solid to talk about when I went on auditions, and soon after that I landed speaking parts on the religious programs Look Up and Live and Lamp Unto My Feet, and the daytime soap opera The Edge of Night.

In the summer of 1958, I got my first leading role, on Eye on New York, a CBS anthology series that reenacted sensational crime stories taken from the tabloid newspapers. My episode was based on a true story about a Brooklyn murder case that was still pending appeal. I was cast as sixteen-year-old William Wynn, who was condemned to die for the armed robbery and murder of a delicatessen owner. I felt the responsibility of portraying this kid whose fate was in limbo as he waited for word from the justice system, and I dove into research.

I pored through court testimony and learned that evidence showed Wynn was 125 feet away from the actual crime scene and had not taken part in the holdup or the murder. It didn’t add up to me. When I learned from CBS that Wynn’s last appeal had been denied and that he was scheduled to be put to death in two weeks, I wrote a note to New York governor W. Averell Harriman explaining what I’d found in the court records and asking the governor to extend a pardon and “temper justice with mercy.”

Within the week, I received a personal letter bearing the seal of the governor’s executive chamber in Albany, which read, in part, “Following a clemency hearing on July 30, 1958, Governor Harriman commuted the sentence of Frye and Wynn from death to life imprisonment…” I don’t know if my letter had anything to do with it, but I was profoundly gratified to think my small effort might have contributed to keeping this young man alive. I wasn’t an activist, but as I discovered then, for the first of many times throughout my career, that didn’t mean my work couldn’t make a difference in people’s lives.