6

As soon as I walked into Joyce Selznick’s office, she looked me up and down with practiced efficiency. She took me in with her eyes, measured my handshake, assessed my height and weight, the sound of my voice, and the level of confidence with which I explained my road to actor from art student.

This was to be expected. It was her job. But she also had a knack for putting me at ease while slicing me up like a scientist creating samples to put under a microscope.

She was casting the movie The Last Angry Man, and my agent had sent me to meet with her in person. I had been told Joyce was going to love me, but I didn’t get that impression. After explaining that the movie was going to star veteran actor Paul Muni as an older doctor whose devotion to residents of a poor, rough area of Brooklyn was the subject of a TV documentary, she straightened a stack of headshots on her desk and said, “I’ll be honest with you. I’m seeing quite a few young men for this part.”

The part was that of Josh Quincy, a disturbed juvenile gang leader suffering from a brain tumor. He was a hoodlum, but a sensitive hoodlum whose plight was a reminder that there’s more to people than you see on the surface. Indeed, despite what I thought was a lack of interest, Joyce kept asking me questions, like I was a puzzle she was attempting to solve.

She wanted to know if I had a favorite artist. I mentioned Käthe Kollwitz, a German painter and printmaker known for her stark, emotional images of women. She asked if there was a particular style of painting I liked. “Chiaroscuro,” I said, explaining, “It’s the contrast between light and dark. I think it very much carries over into my acting style.” Something about me intrigued her. When our time was up, she said the next step would be for me to meet with the film’s director, Danny Mann. “I think he’s going to like you,” she said.

That meeting took place in a conference room at the Columbia Pictures offices. Danny Mann walked into the room a few minutes after I got there and sat down opposite me. He was in his late forties and had brown hair, glasses, and a hint of a smile. He reminded me of a New York intellectual, someone I had seen a hundred times before in a bookstore or a theater. Joyce had advised me to relax and be myself when I met with Danny, and I tried. I admitted that I was not a fighter, not very tough at all, in fact—not like the character Josh Quincy.

But I recalled friends of mine who stole from fruit and vegetable stands when we were younger. They thought it was fun. I wasn’t that kind of kid, I explained. I was more of an observer. I told him about the moneylender in my neighborhood, the guy named Max, whose place on Lenox Avenue was around the corner from my parents’ apartment.

“My friend Alan and I occasionally rode around with him when he collected from those who didn’t pay their debts on time. Max would see us and say, ‘If you boys are bored, let’s go for a ride.’ We sat in the backseat while he smoked his cigar and entertained us with stories as he drove through the neighborhood.”

“Did the situation ever get tight?” Danny asked.

“I remember Max threatening one person,” I said. “The guy paid, and Max got back in the car, chatting as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened, as if it was business as usual. Another time he got in an argument with a bus driver and tossed his cigar butt at him. That’s it. Alan and I had fun.”

Danny liked the story. We also talked about food, art, our parents, the acting classes he took with Sandy Meisner, my dislike of the acting classes I took, and our mutual fascination with Brando. Though I had warned that I wasn’t comfortable talking about myself, I told Danny almost everything, and I guess he liked what he heard. At the end of our meeting, he gave me the job. “I think you’re Josh Quincy,” he said.

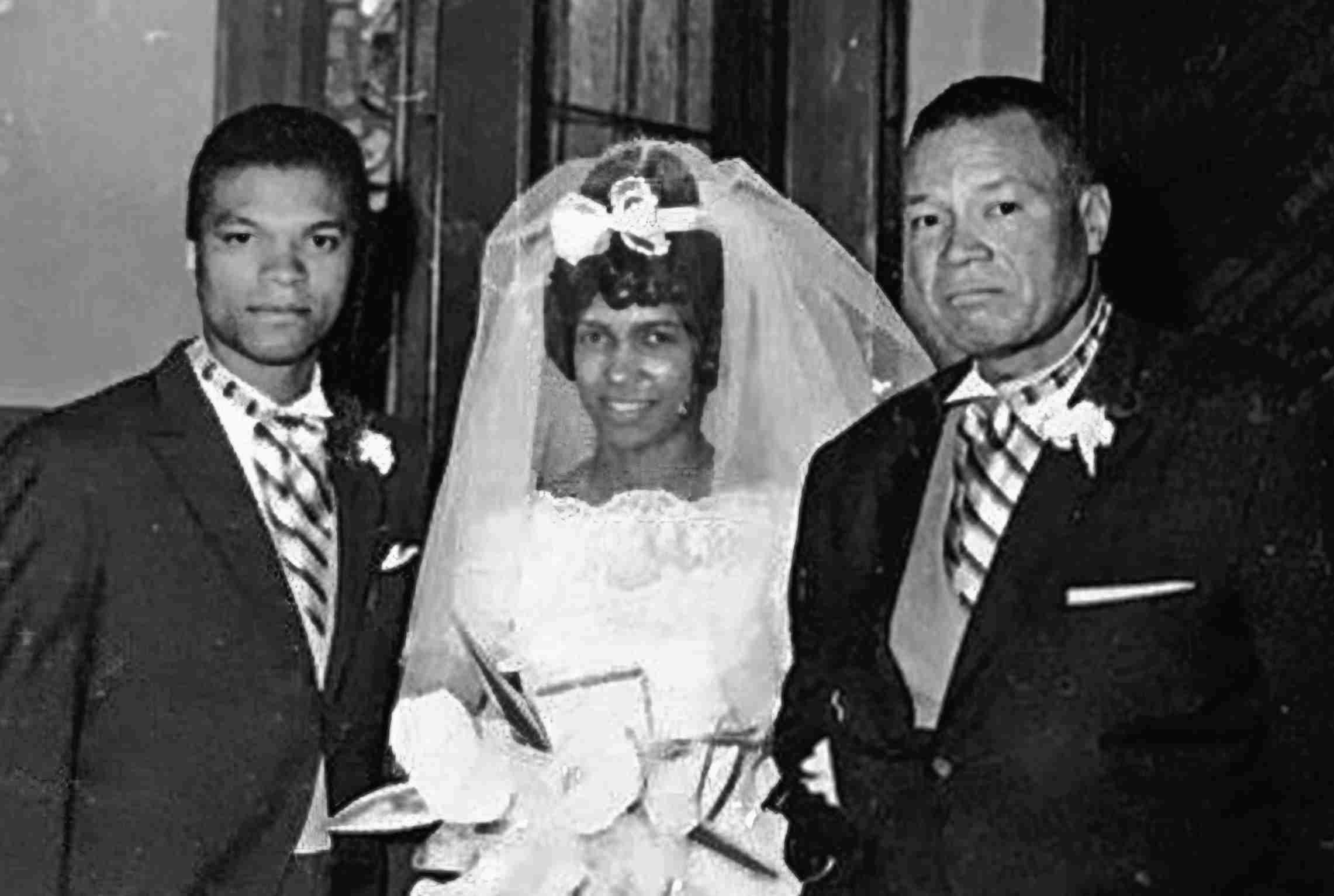

My twin sister’s wedding at the Episcopal Church on Convent Avenue in Harlem, 1962

There was more good news. My sister, finished with NYU and working at AT&T, married a man despite my warning that he was gay, which was true and led them to divorce many years later. But Lady was in love, and her wedding was a major production that took over all our lives. My sister wore a beautiful white gown and veil, and my mother impressed in a new formal. My father and I wore classic black cutaway tuxedos with striped ascots.

But the real star of the evening was my grandmother. Miss Nellie’s gown was custom-made and included a pair of bloomers, which she insisted was a must for a woman of her generation. There were audible gasps when I escorted her into the church and down the aisle. “There’s Mrs. Bodkin,” people whispered, stunned. No one could remember when she had been out of our apartment. “I can’t believe my eyes.”

Then work began on The Last Angry Man. To prepare, I observed mentally ill patients at New York’s Bellevue Hospital. Exterior scenes were shot in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn. One day I met the movie’s two stars: Paul Muni, who played Dr. Samuel “Sam” Abelman, and Luther Adler, who played his friend Dr. Max Vogel. The veteran actors, both in their sixties, invited me to join them for lunch.

They were considerably older and more experienced, and I didn’t know what we were going to talk about, but their funny banter put me at ease. I was a fan of Adler’s. He mostly played villains, but he was a true character actor, with a face that could mold itself into a thousand different looks. His father had contributed to the founding of the Yiddish theater in New York; his sister, Stella Adler, was a renowned acting teacher. Then there was Muni, a master craftsman and one of the true greats. He had won an Academy Award in 1937 for The Story of Louis Pasteur and been nominated four other times. He had also recently won a Tony Award for his starring role in Inherit the Wind.

Both Adler and Muni knew how to explore and present a character, the subtleties of a human being. The way they did it, there were no special effects. You had to act, and act convincingly. With them, the acting was never big or broad; it was just enough. Muni assured me that I was going to learn a lot from them, and Adler nodded in agreement.

“But not about acting,” Muni said.

“No, not that,” Adler concurred.

I had no idea what they were talking about. What else was I going to learn from them?

“We’re going to teach you something better,” Muni said. “We’re going to teach you how to be Jewish.”

As I expected and hoped, every day on the set was an education. I spent most of my time trying to please our Academy Award–winning cinematographer, James Wong Howe, one of moviemaking’s true geniuses and innovators, and an exacting taskmaster. One afternoon we were shooting a scene in which I was supposed to catch a football and say a couple lines. James had blocked the shot according to the sunlight. For some reason, I kept dropping the ball—literally and figuratively—requiring retake after retake.

Each time this happened, I saw James look up at the sun and get more frustrated. Finally, he stepped out from behind the camera and marched up to me.

“You want to be good actor like Marlon Brando?” he yelled in his thick Chinese accent. “You catch ball! You don’t mess up light.”

I caught the ball the very next take.

Another carefully choreographed scene involved me and a friend carrying a sick young woman up to Dr. Abelman’s doorstep in the middle of the night. Godfrey Cambridge played my friend and Cicely Tyson played the young woman. Godfrey had been in the play Take a Giant Step, so both of us knew John Stix, and this was the first of many times I would work with Cicely, who was making her film debut. She had only one scene, and though it was small, her acting had a strength that made it hers.

Day after day, I concentrated on doing a good job, as all of us did, which not only meant following direction but also supporting each other. It was so consuming that it eliminated the possibility of perspective, of taking a step back and seeing I was part of a new generation of young actors who’d landed together in a major motion picture and would continue to cross paths professionally and personally for years.

Decades later, we’d acknowledge each other and the times we had. But in the moment, we were kids finding our way. It was about the work.

One night Godfrey and I shared a car back to the city. At the last minute, actress Joanna Moore jumped in. The driver took off, but he didn’t like the mix in his backseat. We weren’t aware of that until we reached midtown Manhattan and he turned around and made an unsavory remark about his having to pick up two Black men. He didn’t mind Joanna, but we bothered him, and his crack insulted her. Before I knew it, I was pulling Godfrey off the guy’s back. He screamed at us to get out of his car. I was grateful Godfrey didn’t kill him.

Aside from that experience, the set was a safe and occasionally sweet haven from the real world. Early one morning I arrived at the location where we were shooting and immediately slammed my finger in a door. It was not a pleasant way to start the day. The freezing-cold air caused my finger to hurt even worse, and I was in excruciating pain all morning. During a break, I ducked into a tiny store being used as our dressing room. Fancy trailers for the actors didn’t exist back then. I lay down behind some boxes, hoping to nurse my finger and get some rest, since I’d had a predawn call time.

A few minutes later I heard a noise and peeked around the corner. Nancy Pollock, the actress who was playing Muni’s wife, had slipped inside with her real-life husband for a private conversation. They had no idea I was there, hearing everything they said to each other. They spoke so tenderly and lovingly to each other. I had never watched older people having a romance. It was an unexpected gift that deepened my appreciation for this new world of moviemaking and the people in front of and behind the camera.

Then production moved to Los Angeles. My mother kissed me goodbye and told me to have fun in Hollywood. The cross-country flight was my first time on an airplane, and she was more excited than I was. My father was very relieved I had a job but also concerned about my enthusiasm for renting a car in L.A., and he warned me to be careful and to exercise common sense, something both of us knew that I often lacked.

The studio put me up at the Montecito Apartments on Franklin Avenue, in the heart of Hollywood. When I got to my room, I opened my suitcase and found sitting on top a clipping from a New York tabloid about a guy who was decapitated in a car wreck. I laughed. It was my father’s handiwork. I immediately knew he had snuck it into my suitcase—his way of telling me again to be careful.

He also called me every day to make sure I was all right and to say, as he did at the end of each call, “Sonny, don’t get any girls pregnant” and “I love you.”

That was my dad. As an older Black man, he was going to worry about me regardless of how hard I tried to convince him that I was going to be okay. He also knew I was going to have a good time in Los Angeles, and he was right. I saw Katharine Hepburn in a convertible on Sunset Boulevard and spotted Agnes Moorehead at the Farmers Market on Fairfax. But seeing stars paled in comparison to seeing women getting on buses each morning in their nightgowns. “They’re so relaxed out here,” I remarked to my mother on the phone. Of course, I was unaware those nightgowns were called “muumuus” and they were considered stylish.

On the set, I got to know actress Claudia McNeil, who played my mother, and I spent time with actresses Joanna Moore and Betsy Palmer. I was a fun puzzle to Joanna and Betsy, who tried to figure out the many sides they saw of me: shy, serious, and flirtatious. Sometimes I sensed I was the first Black person some of my coworkers had spent time with, and they were surprised they liked me. “Hey, Billy!” an old-timer on the crew said one afternoon. “I gotta tell you, you’re the first colored boy I’ve ever liked.”

No one had ever said anything like that to me before, and I had no response. He took my silence as an indication that he’d said something wrong.

“I’m sorry for referring to you as a boy,” he said. “I didn’t mean to offend.”

I wish I had spent more time with our great cinematographer James Wong Howe. Despite yelling at me in New York, I knew he liked me. One day James convinced me to tie myself to a tree and then get into a squat. We were joking around, and I was too timid to say no to him. As soon as I crouched down, he erupted into laughter and pretended to walk away. I tried to stand up and couldn’t. I was stuck. He laughed even harder.

“I can’t get up,” I said.

“Old Chinese trick,” he cackled. “Nice knowing you, Billy.”

“I gotta work,” I said.

“Don’t be late!”

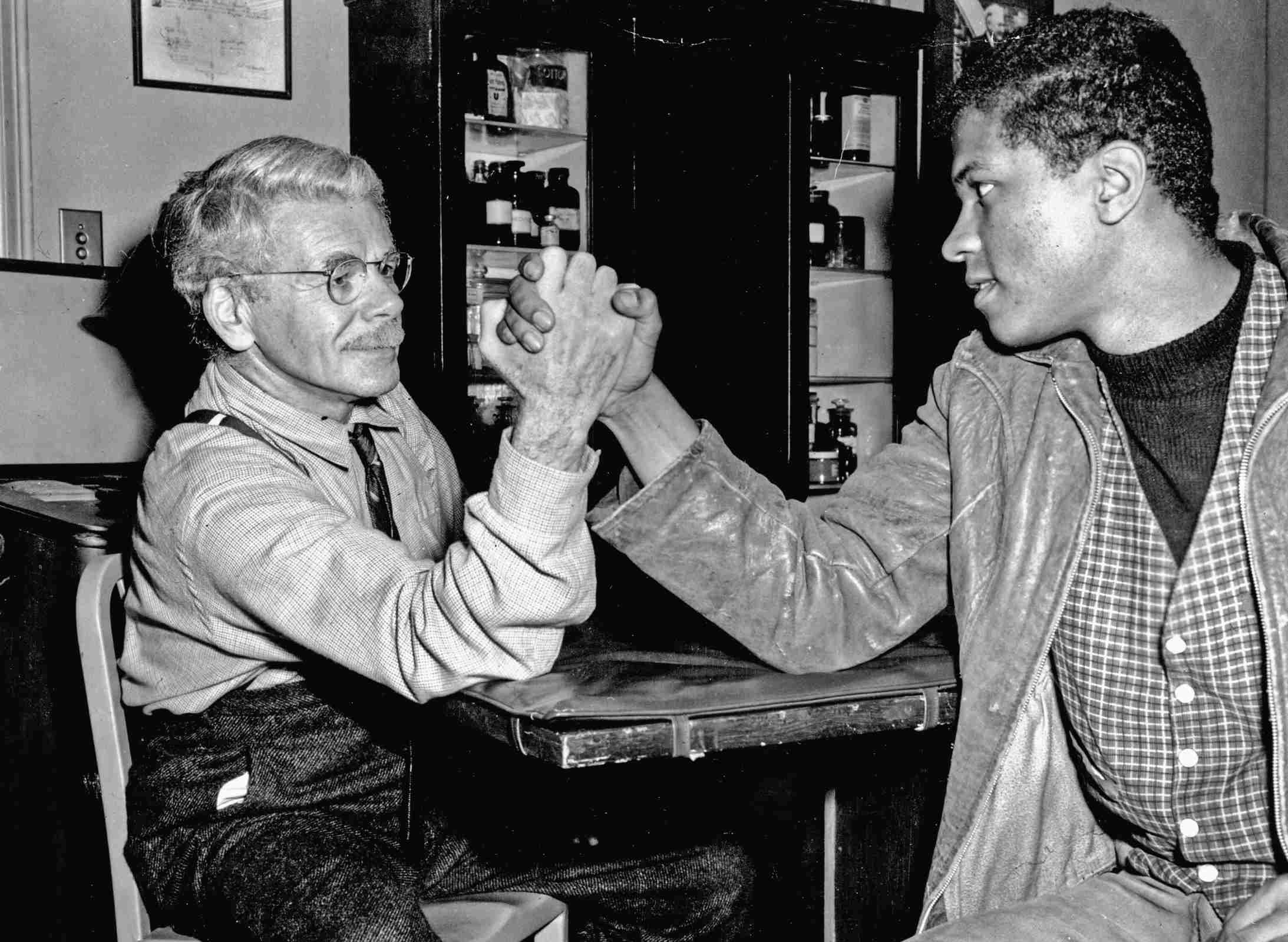

The gentle hazing was part of being the kid among these extraordinary people, and I took it as intended, a sign they liked me. Indeed, Muni had taken me under his wing back in New York and that continued in Hollywood, where we had more time to chat about his roles as Louis Pasteur and Émile Zola. When I asked him about Scarface, one of the gangster films I had loved as a kid, he just laughed and sloughed it off as long ago.

I wanted to impress him, and in one scene I might have tried too hard. In it, we were supposed to arm wrestle. As soon as the director yelled “Action!” I leaned into it and nearly ripped his arm off. Muni stopped the take and told me to follow him to his dressing room. “Listen, Billy,” he said, “I’m an old man and you’re a young man.” Then he showed me how to fake it. “That’s acting,” he said. “Now let’s go back to work.”

The famous arm-wrestling scene with the great Paul Muni in The Last Angry Man

The Last Angry Man was Muni’s first movie since blacklisting and health issues had interrupted his stellar career. Unbeknownst to any of us, this would be his last movie. My favorite part of working with Muni was watching him prepare. It was a master class in how this quintessential character actor approached his work. He was meticulous about his look and makeup; he thought of every detail and mannerism of his character, putting in hours of preparation before ever stepping in front of the camera or onstage.

I took that to heart. Even though my head was often in the clouds, as my sister was fond of saying, I was a pragmatist. I suppose that was my father’s influence—and now Muni’s. I saw how essential it was to do the work. You couldn’t sit around and dream about being a success. You had to put in the hours to make it happen and then prove you could do the job.

My whole career has been about proving I could do the job—proving it to others and to myself. I saw that in Muni, too.

Muni was a perfectionist who was rarely satisfied with his performance. He asked Danny Mann to shoot scenes over and over again. It was hard to say where his perfectionism ended and obsession began. He relied on his wife, Bella. The two of them had been married since 1921. A petite woman, she had his trust and was on the set every day, standing behind the director, watching her husband and quietly signaling him when his take was acceptable and he should move on.

I watched the two of them closely. They fascinated me. He was an amazing talent, but they were an even more amazing team. One day I stood next to Bella and said, “I need to know how you let him know what he’s doing is okay.” She smiled at me and put a finger to her lips, letting me know that was private and between them. It was a beautiful gesture that answered my question, and I left it there.

They had me over to their house for dinner several times. It might seem odd to some that this older, accomplished Jewish couple would take an interest in a young, inexperienced Black actor, but they liked me, and my personality was such that I happily drifted into almost any situation that seemed interesting. And they couldn’t have been more interesting. I joked I was a nice Jewish boy, minus the “Jewish.” The Munis loved it. They were health nuts, lecturing me on the dangers of salt and advising me to eat fresh food and exercise.

But acting was always the main topic at these dinners, and no one was better at talking about the craft than Muni. He was a master mimic who could transform himself into a completely different person in front of my eyes while telling a story. He spoke about the versatility acting required and believed an actor should be able to play any part—young or old, male or female. As a twelve-year-old, he had played an eighty-year-old onstage.

That made sense to me. It offered the appealing and hopeful sense of possibility—that I could in theory play anything without being limited by my race, sex, or looks. When I acted, I wanted people to see the character I was trying to portray, not me, a skinny young Black man from Harlem. That was the challenge of acting and any other art, including painting and singing—to transport the audience, to make them believe, to open their minds to a new experience or emotions that brought them closer to understanding the range and depth and commonality of being human.

Muni concurred.

“But you have to have the talent do it,” he said. “Not everyone can.”

Not everything was serious. After all, I was a young man and on my own in Los Angeles with a generous per diem for food and living expenses. That itself was a license to have fun. Although I had my longtime girlfriend back home—she was in college—I still managed to fall in love—and by “love,” I mean becoming infatuated with young women.

There was one named Amanda. We met one night at a restaurant. She was a pretty girl from South Central by way of Mexico, with large brown eyes that had their own gravitational pull. I couldn’t stop looking at her—or thinking about her. After making a date with her, though, I realized I had no way to pick her up. I turned to Luther Adler for help. He had a suite in my hotel. He also had a car, a Nash Metropolitan. I also knew he was entertaining a lady friend that evening and didn’t need his car. I knocked on his door.

“Uh, sorry to bother you, but I have a favor to ask,” I said.

He nodded. “How can I help?”

We stood in the dimly lit entry of his suite while I explained the situation and asked to borrow his car. Without inquiring whether I had a license or even knew how to drive—which I did but hadn’t done in a while—he darted into his room, returned a few seconds later, and tossed me the keys.

After a few dates, Amanda made it clear that she saw me more like a kid brother than a boyfriend. She then introduced me to one of her friends, who seemed to share my casual demeanor. But she turned out to be an explosive source of drama that was too much, so I broke that off and decided to go out alone. One night I saw John Coltrane perform at a club in West Hollywood. His tenor saxophone produced a flurry of chords and shifting sounds and scales that was brilliant. As I left the club that night, I knew I had witnessed true music-making genius that I would remember for the rest of my life.

My favorite hangout was Barney’s Beanery, a West Hollywood watering hole popular among actors and others in the industry. I got to know a guy there, a writer-actor whose father was an Oscar-winning writer and producer. In other words, a tough act to follow. One night, over dinner and a few drinks, we talked about our fathers, and he mentioned being troubled by the fact that his had recently passed away without the two of them ever having resolved their differences.

I don’t know that I offered any helpful advice, but his pain had a profound effect on me. I was at the age when young men don’t always see eye to eye with their fathers, and that was true to some extent of me and my father, who would have preferred me pursuing a more stable lifestyle and occupation, like my sister, who was married and working at AT&T. But I saw in my father a remarkable man who was hardworking, devoted, intelligent, curious, and loving. He never asked for anything for himself. He was simply good.

The next night, I returned to Barney’s, settled in a corner booth in the back, and wrote my father a letter. In it, I told him how much I loved and admired him, and understood and appreciated his struggle and the sacrifices he had made as a man who put caring for his family at the top of his life’s goals. I knew he wished I was physically tougher, but I assured him that he’d taught me something more important—to be a loving, caring, thoughtful human being. He needn’t worry about me, I said. I was going to be okay.