14

Corey and I were at the Hollywood YMCA, a beautiful Spanish colonial building designed by noted Black architect Paul Williams back in the Golden Age of Hollywood. I was running on the rooftop track, sweat pouring off me as the summer sun beat down on my skin. Corey, fourteen years old, had come up from the weight room to watch me. Impressed, he shouted out encouragement. “Pretty good, Dad!”

After a few more laps, I stopped, toweled off, and caught my breath. At thirty-seven, I was in decent shape. It was part of the job.

“Grandma used to tell me that you lifted weights when you were a kid,” Corey said.

“I started when I was around your age,” I said. “With my friend Dickie Stroud.”

“She said you were muscle-bound.”

“I don’t know what that means,” I said. “But if it comes from Grandmommy and concerns me, it probably has more than one meaning.”

Corey burst into laughter, and soon I was laughing with him. In those days the two of us shared more than look-alike smiles and a sense of humor. A year earlier, after turning thirteen, he had chosen to move to L.A. and live with Teruko, Miyako, Hanako, and me. If there was a happier kid, I hadn’t met him or her. Yet his decision to leave his mom was not an easy one for anyone, not for him and especially not for Audrey. She was a wonderful mother—or, as Corey said, “the best mom ever!”

Audrey and I worked together to make sure Corey felt loved and secure. I made sure he went to top private schools and was surrounded by positive, productive people.

But after Audrey’s second marriage ended, they moved to a small apartment on Central Park West, and between her work and his activities, she worried that he might not be getting the supervision he needed or all the opportunities he could have in our house. The two of us had many long talks about his well-being and future. Knowing how close Corey and I were, Audrey gave him a choice to stay with her or move in with us out West. I couldn’t have done that; it was a testament to her desire to see him have all the advantages we could provide. Ultimately, though, she left the decision up to him.

“You’re going to be a man and you’re going to make your own decisions and you’re going to have to live by those decisions,” she told him.

Corey was sensitive and aware of everyone’s feelings. He knew it was hard on his mom when he left. He worried about her. She had asthma, and climbing the stairs to the fifth-floor walk-up sometimes left her out of breath. She’d taught him to cook, and he would have dinner waiting for her when she came home. To Audrey’s credit, he arrived a polite, capable, and likable young man. He played guitar, loved sports, and was independent. Like most kids in New York City, he’d started riding the bus on his own in third or fourth grade.

I was thrilled to see him every day. I took him with me to the gym, and I made sure he met some of the kids in the neighborhood. He signed up for a filmmaking course in school, and I got him martial arts lessons with the master of all masters, Hugh Van Putten. It was a fairly normal life for a kid—if normal is having a mother who hosts a weekly high-stakes poker game whose regulars include Henry Fonda and Richard Pryor, and having a girlfriend at school whose mom schemes to meet your father.

That happened! Corey’s friend was named Angela. “She’s a cute Black girl,” he told me. “I’m going to ask her to go steady.” The girl’s mother brought her to the house to hang out one day, and when they got to our place, she invited herself to stay and talk with me. The little girl broke up with Corey a few weeks later, and when I asked why, Corey said, “She only agreed to be my girlfriend so her mom could meet you.”

Berry Gordy was Hanako’s godfather. One day he called the house, excited about another script he thought was the perfect follow-up to Lady Sings the Blues.

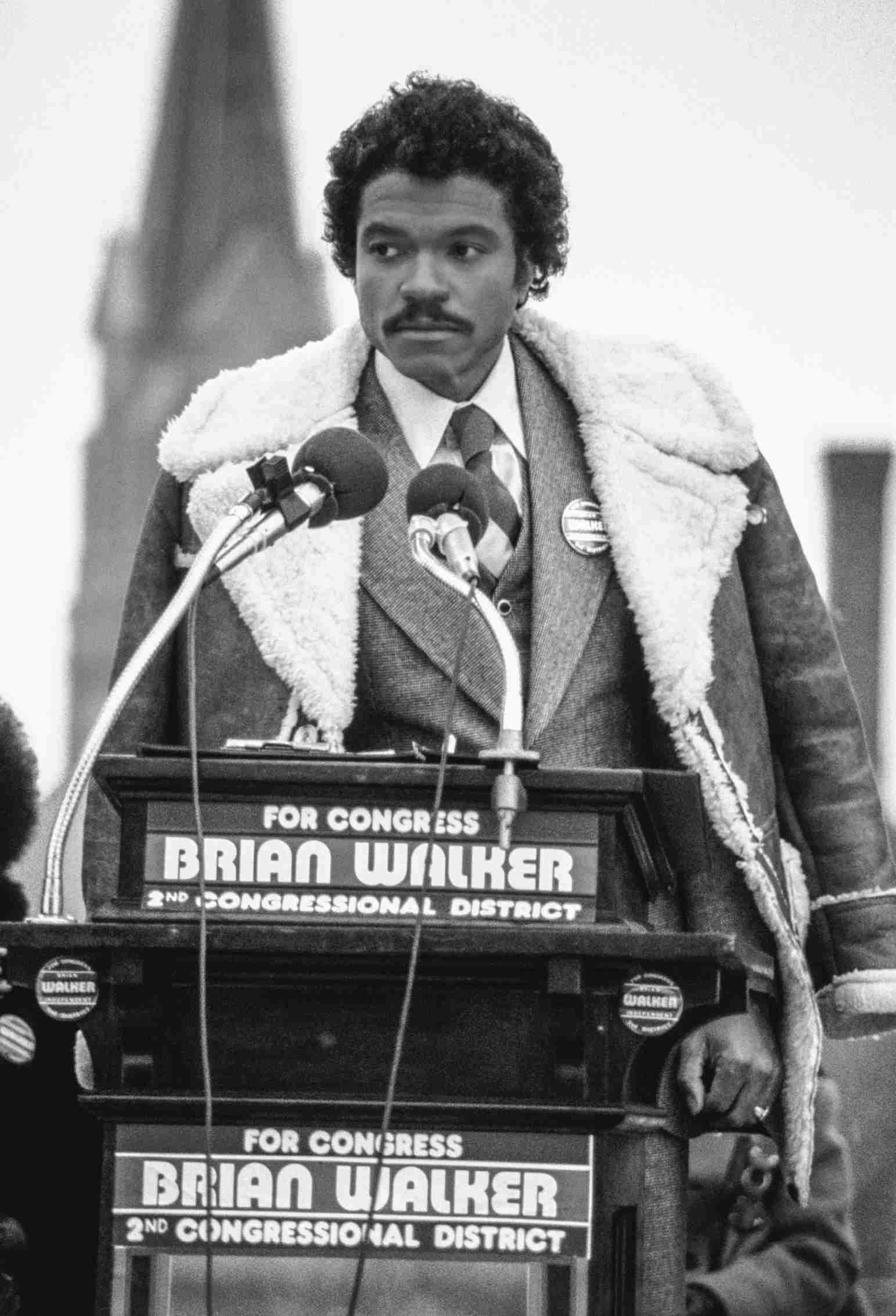

The picture was Mahogany, and it was the story of a Chicago political activist named Brian Walker who falls in love with department store salesgirl and aspiring fashion designer and model Tracy Chambers. Discovered by a top photographer, she goes off to Italy and soars to the top of the fashion world. The characters tapped into the zeitgeist; models Beverly Johnson, Iman, and Pat Cleveland were showing the world that Black was truly beautiful, and Black Power was transitioning from the Panthers into politics. Atlanta, Detroit, and Los Angeles had all elected their first Black mayor, and Barry White, Donna Summer, and Stevie Wonder had crossed over into the mainstream.

There was a sense of progress and possibility, and Berry saw that re-teaming Diana and me was like throwing gasoline on that fire. I viewed it as a chance for the two of us, Diana and me, to join the ranks of the silver screen’s classic couples as long as the movie delivered what the audience wanted, which was a good romance.

By the time work began, Diana and Berry’s real-life love affair had come to an end, but that didn’t interfere with the shared mission of making a hit movie. As for Diana and me, we were like two kids getting back together on the playground after summer vacation. We started shooting at Paramount, and sparks flew as soon as we saw each other. It was one of those things where the electricity was real. It’s why I understand when people wondered if Diana and I ever had an affair. As interesting as it is to imagine, we never did.

That doesn’t mean it couldn’t have happened, but I think the fact that it didn’t ensured the heat was always on high when we did get together in front of the camera, and that was always the top priority for both of us, doing great work.

Berry felt the same way, which was why he fired director Tony Richardson ten days into production. I respected Tony, who’d directed me way back in A Taste of Honey and given me advice that was essential to my development as an actor. But we were out of sync this time. I disagreed when he asked me to put more Jesse Jackson into my character. I understood why he had asked, but it didn’t fit my approach to the character. I didn’t want to imitate anyone. I went in my own direction.

The wonderful last scene in Mahogany—but it was so cold in Chicago that day, I could barely get the lines out.

Tony couldn’t get the feel Berry wanted. He didn’t know the world that Berry wanted to capture onscreen. Berry also wanted to follow the same moviemaking formula that made Lady so popular—a splashy, dramatic love story with an upbeat ending, basically another old-fashioned Hollywood crowd-pleaser. To Berry, Mahogany was a follow-up to Lady Sings the Blues, only this time Diana and I were going to have our happily-ever-after. Berry knew it was the fantasy audiences wanted. It’s why he hired himself as Tony’s replacement.

Once we finished shooting at Paramount, the production moved to Chicago for a month of location work. It was early December 1974 and freezing cold there. Diana’s scenes showed Tracy Chambers pursuing her dream as she rose from salesgirl to buyer to fashion designer. Almost all her shots were indoors, and I teased her about being too comfortable because the opposite was true for me. Almost all my scenes involved my character campaigning outdoors in his South Chicago neighborhood.

We shot them outside in the frigid, below-freezing air. The wind was blowing in off the lake and I had never been so cold. I wore the warmest coat I could find, a heavy shearling sheepskin that I kept for years, and still every single bone in my body was frozen. Before production wrapped in Chicago, I crossed paths with my old friend Al Duckett, who was also doing some work there. When he heard that I was playing a community activist, he persuaded me to accompany him to a meeting with some real-life political activists. I went out of respect to Al, and they tried their best to sign me up, but I politely explained that I was like Ellington, who expressed his beliefs through his music, and I did the same thing through my work.

Then production of Mahogany moved to Rome. I’d read about this city since I was a kid without ever having visited, so once there I was eager to see the Colosseum, the Pantheon, the Vatican, and the art of Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini, and Caravaggio. I wanted to explore the streets, breathe the air, and experience the warmth and spirit of the Italian people. Berry was all business and looked oblivious to the change of scenery. As director, producer, and chief perfectionist, he kept tinkering with the script, working to get the key moments just right.

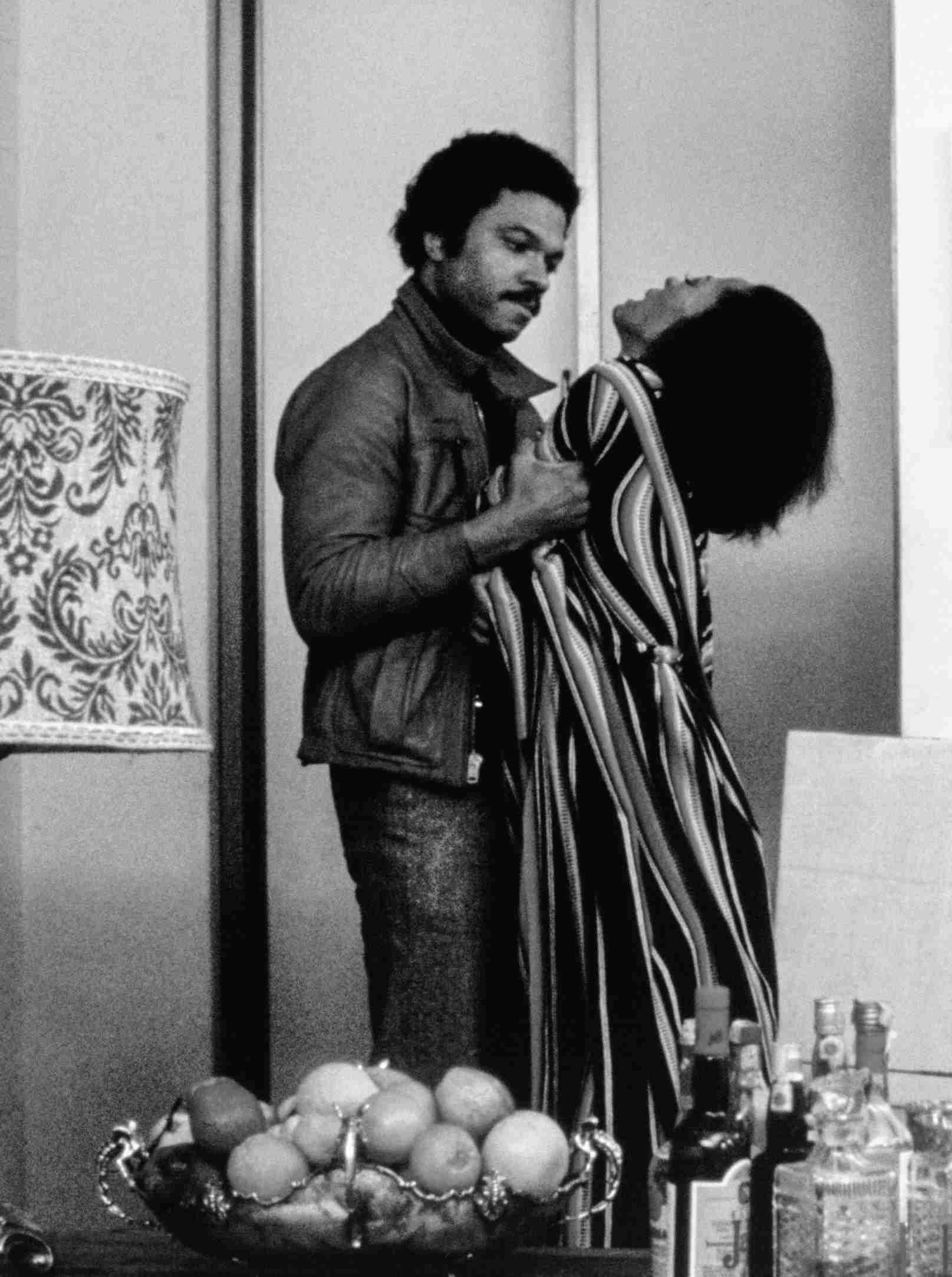

He knew the scene in which Brian Walker shows up in Tracy Chambers’s dressing room following a triumphant fashion show in Rome, hoping to win her back and take her with him to Chicago, still needed work. Something was missing, and getting it right was crucial to getting the entire movie right. Tracy was at the peak of her meteoric rise to fame, yet she couldn’t see or wouldn’t admit she was miserable. She blamed her boyfriend instead. “I’m a success, Brian,” she says. “And you can’t stand it.”

Their entire relationship came down to that moment. Would they have a future together? Would she see that she was blowing it? Would he fight to make her see that he loved her and she wasn’t just behaving badly, she was wrong? The scene had to be as tightly crafted as a pop song. It needed a great line, a line that spoke truth to emotion, the line that moviegoers were going to repeat and remember long after they left the theater. Here’s looking at you, kid. Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn. Love means never having to say you’re sorry.

A tough scene, with the best line in Mahogany: “Success is nothing without someone you love to share it with.”

Berry knew this, just like he knew all the classic movie lines by heart. And it was while we were in Italy that he finally came up with the line. I remember reading it and thinking, Brilliant, that’s it. In the scene, after being accused that he couldn’t stand her success, my character, Brian Walker, was on the way out of Tracy’s dressing room, bags in hand, when she dumped her drink on the back of his head and cackled that no one loved her before scampering across the room. She was acting out, trying to get him to fight back and prove her wrong. I turned around, grabbed Tracy/Diana, and gave her a look of truth, staring her in the face whether she liked it or not.

“Let me tell you something and don’t you ever forget it,” I said. “Success is nothing without someone you love to share it with.”

That was it, the line. And as I walked back to the door and picked up my bags, I added, “If you ever become Tracy Chambers again, you know where I’ll be.”

We did numerous takes from every angle, and by the time Berry was satisfied that he had the scene, we were exhausted—and smiling like little kids. “Oooh, that was fun,” Diana said. Agreed. We had already shot the last scene back in Chicago, in which Brian Walker is heckled while giving a campaign speech. One man interrupts. Then from deep in the crowd a woman shouts that she’s a widow from the South Side whose old man left her with six kids, all of whom have the flu. What’s he going to do about that? The crowd buzzes with support for her. He recognizes the voice but can’t see who said it. He asks the lady who said it to step forward.

“Mr. Walker, when you’re elected, what are you going to do to help me?” she shouts, once again putting him on the spot.

The crowd parts. She emerges. He sees it’s Tracy. The theme music starts to play. He smiles.

“Do you want me to help you with your landlord, lady?” he asks.

“Hell no,” she says. “I want you to get me my old man back.”

I won’t spoil the rest, other than to say he guarantees he will get her old man back, she says he has her vote, they kiss, and we had a hit movie.

Before leaving Rome, I remembered a former girlfriend lived there. The last I knew, Yvonne Taylor had married a count and was living a fabulous life in Italy. I got in touch with her, and, happy to hear my voice, she invited me to a party at her villa. When we’d lived together, she was always throwing a party. I guessed little had changed.

I was right. Her place was a multistory mansion. The downstairs area was large, opulent, furnished for parties. Yvonne greeted me warmly and introduced me to some of her Italian friends, including actress Maria Schneider, who’d co-starred with Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris. Maria was there with her girlfriend. I noticed a monkey running around the room. Yvonne acknowledged it with a smile, as if it were commonplace. It was that kind of party, European and exotic.

After a while, I didn’t feel like mingling anymore, but I was not quite ready to go back to my hotel and stretched out on a couch instead. It was a fine place to observe Yvonne’s eclectic friends. I guess I was more tired than I thought. I started to drift off, but as I did, someone lay down next to me and pressed their body close to mine. I opened one eye and found myself staring at Maria Schneider. She was giving me every indication that she wanted something to happen between us. Before I could even consider that option, I felt a strong jolt against the sofa. It was Maria’s girlfriend, standing over us, upset.

Oh my God, I thought, I was back in Yvonne’s crazy web. No thank you, not again. I found Yvonne. Arrivederci, my friend.

Mahogany opened on October 8, 1975. The critics panned it. Berry said it had the worst reviews of any movie in history. Moviegoers thought otherwise; they lined up eager to decide for themselves. One New York theater screened the film twenty-four hours a day. In an interview, film critic Roger Ebert asked me why I thought people were turning out despite the critics. I said it satisfied the need for fantasy. Who didn’t like a good love story?

Love was the universal language of people. It transcended skin color, culture, economics, and just about everything else that divided people.

But the movie had more to it. We portrayed Black people with lives that were glamorous, influential, upwardly mobile, and international. We showed their potential and ambition, as opposed to stereotypes of being stuck in the ghetto and mired in poverty and crime—and audiences of every color responded. Diana was hailed as a superstar who could sing and act. The press referred to me as “the Black Clark Gable.” I didn’t understand why I had to be labeled a “Black” anything, but fine, I was recognized as a romantic leading man, a Black romantic leading man, and that was a first for Hollywood.

My fans came in all shapes, sizes, and colors, and I don’t think they paused to consider the shade of my skin. To them, I was simply Billy Dee, their “man” or their “main man,” as some cooed, and that was more than enough for them. At a promotional event at a Baltimore department store, a woman asked if she could give me a hug. Before I could get my arms around her, she passed out. “Look, she’s still smiling,” said the woman in line behind her.

At a similar event in another city, a woman reached the front of the line and scowled at me. “You shaved your mustache!” she said. “Why would you do a thing like that?” Another woman cut in. “That’s okay, Billy. I’ll keep you company while it grows back.”

Sometimes the attention could get a little absurd. But life was fun. I enjoyed myself.

Mahogany was followed by one of my favorite movies, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings. (I’d worked on the picture the summer before Mahogany was released.) Based on William Brashler’s acclaimed novel about the Negro Baseball Leagues in the 1930s, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings told the story of an all-Black team of all-star baseball players who split from the old Negro National League and barnstormed across the South and Midwest, hustling pickup games to make a living after the Great Depression.

This was long before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, and these were some of the most extraordinary athletes to ever pitch, hit, run, and catch. They played in all sorts of circumstances, often for money, sometimes simply for the love of the game, but always knowing they were among the best to ever step onto a diamond despite being barred from competing in all-White Major League Baseball.

My character was loosely based on pitching legend Satchel Paige. James Earl Jones played Paige’s best friend, Leon Carter, a character drawn from catcher Josh Gibson, the greatest home run hitter ever to play the game. And Richard Pryor was a scrappy ballplayer trying to pass his way into the major leagues any way he could. This was an important but little-known slice of American history, and I wanted to do whatever needed to be done to honor the legends we were depicting onscreen, starting with a trip to Florida to get in shape.

Because I was playing one of the greatest fastball-slinging pitchers of all time, I wanted to look as authentic as possible, so I trained with former major leaguers. They helped me develop a classic pitching motion. I managed a sore arm on my own. I had been a pitcher on my baseball team as a kid, but I hadn’t played since then, roughly thirty years, and I felt every one of those years after my workouts. But baseball great Willie Mays saw footage of me and said I threw like St. Louis Cardinals flamethrower Bob Gibson, so the pain was worth it.

We shot on location in and around Macon, Georgia, and director John Badham had concerns about bringing a large cast of Black actors and ballplayers into town for nearly two months. He’d grown up in Georgia and was well acquainted with the prejudices in that area of the country. However, the locals offered a warm welcome to us. Some might’ve been too welcoming, in fact. One afternoon the tactical police force had to restrain a crowd of overly enthusiastic admirers at the ball field.

I loved working with James Earl Jones— here in Bingo Long, 1975.

For all the complicated logistics and choreography involved in staging baseball games, the shoot was relaxed. Baseball is full of rituals, and I developed a good one, starting most days by kissing James Earl on the top of his head, as my father used to do with family and close friends. Unfortunately, I no longer had that type of relationship with Richard. Our once-close friendship had unraveled back in L.A. when I witnessed him abuse his girlfriend, Patricia, verbally and physically. It wasn’t a onetime incident, either. Then Teruko and I saw him strike her with a still-smoldering log he took out of the fireplace, and that ended our friendship. I couldn’t be around someone who behaved that way. He knew that, and it made working together on Bingo tense.

For me, the best part of shooting that movie was having Corey on location with me. School was out for the summer, and I never wanted him to feel his father didn’t want to be involved in his life or that he wasn’t the most important part of it, so I flew him to Georgia. Corey brought his best friend, and the two of them created a daily newsletter that became a popular source of information among the cast and crew. “All the restaurants in Macon close early except the Waffle House!” they wrote. “It’s open twenty-four hours! And they have some of the best fried chicken ever!”

Corey at fourteen, having fun on the set of Bingo Long, 1975

I’d never been to the South, and I had mixed feelings about going because of the history there. I was uneasy about what I might encounter, yet I was curious and eager to explore the area for myself. Before going, I read Jean Toomer’s novel Cane, a mix of short stories, poems, sketches, and dialogue that was set mostly in Georgia, and his descriptions of the red clay, the dense greenery, and the unceasing chorus of belching bullfrogs at night painted a picture of that area that I couldn’t wait to see.

I was so obsessed with Toomer’s book that I took out an option on it, hoping to develop it into a movie. Published during the Harlem Renaissance in 1923, Cane told the story of six women connected through their interactions with a light-skinned Black man who moves to Georgia from the North to teach school and write poetry. As he gets situated there, he’s confronted by the hypocrisy of the South’s piousness and prejudices, its devotion to religion and its deeply ingrained bigotry. The book was based on Toomer’s own experiences as a man from mixed parentage who grew up Black yet was light enough to pass for Caucasian, and his resulting struggle with identity—the lies some of us tell ourselves, the lies we’re forced to tell, and ultimately the need to tell the truth.

I had my own brief history of doubt. Once, when I was beginning my acting career, I tried making myself darker by lying under a sunlamp; I just ended up with a blistering sunburn—itself a painful lesson of the consequences of trying to be someone other than yourself. I embraced every drop of Black, West Indian, Native American, and Irish blood in me, as well as the beautiful brown skin this eclectic recipe of DNA gave me. I was truly the full spectrum of colors and didn’t want to be labeled anything but an actor, a man, a father, and a human being. No qualifiers necessary. But that was me.

My uncle Bill had a good friend named Joe Pope whose skin was whiter than most White people, except that he was Black. A lifelong Harlem resident, he embraced everything about being Black: family, history, culture, food, fashion, style, music. He was Blacker than the darkest-skinned person you could find. There was just one problem: No one believed that he was Black. People thought he was lying. It was a cruel irony.

My grandmother’s mother, a West Indian beauty, had a similar look. She didn’t appear to have a drop of Black blood in her and it annoyed her anytime someone doubted her. In a wonderful twist, she didn’t want to be White. But why would you want to be anything other than who and what you are? It’s a denial of reality, a rejection of the gift of life. What too many people have a hard time seeing is that none of us are one color, and the color that we appear to be is only one shade of the many colors that make up our humanity.

Bingo Long is a story about ballplayers battling for recognition and acceptance of who they were without having to compromise. The crime of trying to be anything but yourself is illustrated through a stinging twist of fate through Richard’s character. He has tried throughout the film to pass his way into the big leagues, first as Cuban and most recently as Native American, anything but who is really is. Then he hears that a Black rookie has been signed to a minor-league contract and is finally going to break baseball’s color barrier. “Great,” he says, “now that I’m Indian, the Whites start hiring the coloreds.”

Thanks to Toomer and the time I spent in Georgia, thoughts and feelings about race percolated in me for years, eventually resulting in paintings that I called my Sambo series. Satiric, harsh, biting, political, proud, and sad, these pieces told the tragic history of Black people in America—a history of struggle not just for freedom, equality, and opportunity, but also for pride and love and identity as a human being.

Each painting included a Sambo caricature on the canvas as a way of illustrating what I’d seen and heard all my life but especially over that summer in the South, the way I’d seen Black people looked at, the way I’d heard people casually refer to Black people as “niggers,” as if it were 1875 instead of 1975, and the insecurity I’d seen in Black people’s eyes despite the smile on their face. It was my absurdist sense of humor minus the laughter, throwing the clownlike image given us back at the world, like the way Jimmy Baldwin would call himself an “ugly little Black faggot,” daring someone to say otherwise as he laughed.

Jimmy had referred to Black people who suffered the loss of themselves as “Sambos of the world,” and my Sambo wore the sad, confused expression I had seen on so many people in the South, and on men during my childhood in Harlem. It was a deep pain, an existential suffering, one that gripped the soul and turned life into a conflict of knowing you were human but not being allowed even that dignity, being told you were less than.

I was in this rarified orbit of being loved, but I remember thinking, What does it mean to be despised? What effect does it have to know you are despised? Jimmy frequently used that word: “despised.” What did it mean to be despised for who you were, for the randomness of the way you entered this world? Underneath one painting I wrote words that spelled it out even more plainly:

What do I do now d’at I am no longer—uh—what are those names?

Nigger Coon Boy Rastus Uncle Lacy Black Colored African-American…

Who am I?

Where do I belong?

The final painting in the series showed Lena Horne going to MGM for a meeting with the studio bigwigs. I contrasted her beauty against stereotypical mammy and Uncle Tom caricatures in the background, and right below her were illustrations of studio chief Louis B. Mayer, his secretary, and one of his writer-directors. Beneath them was the brief dialogue I imagined them having as they met with her:

“What do we do with her?”

“She’s beautiful.”

“But she’s Black.”

I could’ve put myself in that painting. Actually, I did.

During the early 1970s, I turned down numerous roles in blaxploitation movies. The genre had carved out a place in the business, and I understood the need for Black filmmakers to have an outlet for Black stories with Black heroes when Hollywood didn’t offer those prospects. But I thought the genre itself and its willingness to be labeled limited the appeal of those movies and anyone in them. It put them in a box. And once in a box, how do you get out of it?

I was about avoiding any and all boxes. I’d always felt this way. My conversations with Paul Muni and Laurence Olivier had spoiled me forever as an actor. Having both of those greats tell me that I can and should play any character I want to play no matter the way I look or the color of my skin filled me with high expectations and a belief in artistic freedom of expression. It was unrealistic, but I never sought any reality other than my own.

Berry Gordy, my brother in the movies, had been developing a biographical movie on composer Scott Joplin’s life and music since the early days of Mahogany. My manager, Shelly Berger, sent me the script for Scott Joplin when I was still down South, and after reading the draft, I wanted to be involved. I loved ragtime. I also saw an opportunity to interpret this great American composer in a way that might surprise people.

Joplin was known as the King of Ragtime. His music had been rediscovered a few years earlier after it was featured start to finish in the Oscar-winning movie The Sting. But his life was less well known. A musical prodigy, he came from a family of railroad workers, traveled as a piano player, composed two operas and a ballet, wrote a hit Broadway musical, and died under tragic circumstances while still a young man. His composition “Maple Leaf Rag” made him a star. But Joplin wanted to be known as a serious composer, and America wasn’t ready or willing to give that stature to a Black man, even one as great as Joplin.

Ruthless, unscrupulous publishers took advantage of him. Money issues resulted in the score of his first opera being seized—and lost—by a storage facility to which he was in debt. He died from syphilis in 1917, at age forty-eight, and, though he was known as the King of Ragtime, he was buried in a pauper’s grave.

The movie co-starred Clifton Davis, whom I knew from New York; Art Carney; and real-life musicians Otis Day, Taj Mahal, and Spo-De-Odee. The Commodores appeared as a group of minstrel singers, and Eubie Blake, the great pianist and songwriter, who was in his late eighties and had the longest fingers I’d ever seen on a human being, added a link of authenticity directly to Joplin himself.

After scoring well with test audiences, Scott Joplin was given a brief theatrical release before premiering on TV as a special event. I thought the movie deserved more recognition than it received. The absence of a happy ending might have prevented it from gaining wider popularity, but it was and remains a solid piece of work, worth checking out. I hoped Joplin would be the first of many historical figures I portrayed onscreen, a list that I imagined including Haile Selassie, Hannibal, King Solomon, and Alexander Pushkin, who was mulatto.

My friend Geoffrey Holder, a man with a dazzling intellect and personality matched only by his wife, the extraordinary dancer-choreographer Carmen de Lavallade, pleaded with me to play Alexandre Dumas—the prolific author and prolific lover. I argued that Geoffrey should play Dumas. His larger-than-life persona was perfect. He thought I had the dashing flair required to bring the French author of The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo to life. Like Pushkin, Dumas was another famous mulatto, who leaned into his African heritage, once snapping to a man who dared insult him: “My father was a mulatto, my grandfather was a Negro, and my great-grandfather a monkey. You see, sir, my family starts where yours ends.”

Geoffrey and I had fun taking walks and debating each other, and to this day I can’t say which one of us would’ve ended up as Dumas, because, despite years of trying, he was never able to raise the money needed to make the movie. Too bad.

The one person I wanted to play more than any other was Duke Ellington. I was probably too young to star as Ellington then, but I frequently thought about his life as a movie and knew with every fiber in my body it was a part I was destined to play. Berry and I saw Ellington perform about a year before he died. After the show, we waited in his dressing room, and I thought about all the things I wanted to say to him. Mostly I wanted his blessing for me to play him on the big screen.

I watched Ellington work his way around his large dressing room the way I had done years earlier at Al Duckett’s reception for him. Even in his aged and weaker state, he was still remarkable, charm and genius wrapped up in one man, not only musically but also in his ability to entertain his guests. I never spoke to him, not in the way I wanted. I was too intimidated. Finally, Berry gave me the look. We had to go. I made my way over to Ellington and thanked him.

Perhaps that’s all the interaction I was supposed to have with him that night. Watch him, learn from him, appreciate him, and thank him.