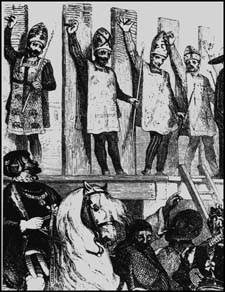

Used as an adjunct to the Spanish Inquisition’s memorably cruel punishments of torture and burning at the stake, the auto-de-fe (literally ‘act of faith’ in Spanish) was a public ceremony where both the condemned and those who had repented their ‘heresies’ were forced to parade through the streets of town in vast processions while displaying physical signs of their particular transgressions. Some wore signs around their neck with their crime written for all to read while others, who had recanted and were to be spared the burning post, wore inverted flames sewn to the back of their gowns. Those who were to be burnt wore upright flames. When the parade reached the appointed place, the entire assembly took part in a religious service before the condemned were handed over to secular authorities to be run through a nearly instantaneous justice mill before being tied to a burning post and set on fire.

Auto-de-fe.

(See also Scold’s Bridle.) These devices (which are closely related to the scold’s bridle described below in this section) existed in a wide variety of fantastical and sometimes downright artistic styles from about 1500 to 1800. They were used to punish those who, by their words, had transgressed against the prevailing conventions. In the course of four centuries, countless women decried as ‘scolds’ and ‘shrews’ because domestic slavery and incessant pregnancy reduced them to neurasthenia and frenzy were thus humiliated and tortured; political power thus held up to public ridicule the petty disobedient and the nonconformists; ecclesiastical power thus punished a long list of lesser infractions. The overwhelming majority of victims were always women, and the operative principle was mulier taceat in ecclesia, ‘Let the woman be silent in church’ – ‘church’ here meaning the ruling ecclesiastical and secular hierarchies, both constitutionally gynaecophobic. The sense was thus: ‘Let the woman be silent in the presence of the male’. The victims, locked into the masks and staked out in the town square, were also treated roughly by the crowd. Painful beatings, besmearing with faeces and urine, and serious, sometimes fatal wounding (especially in the breasts, anus and vagina) was their lot.

Brank.

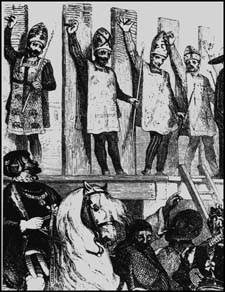

Chinese double cangue.

This Chinese device, alternately known as the fcan hao, tcha and ea, was a massive wooden collar worn by those condemned to display their crime in public for a prescribed period of time. The donut-like cangue was made in two sections, held together by a hinge, which could be opened up to allow the victim to place their head into a hole in the centre. The collar was then closed and locked into place. The cangue made it impossible for the wearer to lie down or, in the most extreme and unusual instances of size, even to walk or stand up without risking breaking his neck. Not to mention the complete impossibility of reaching one’s own mouth to eat or drink, thereby having to rely on the charitable compassion of others.

Chucking stool.

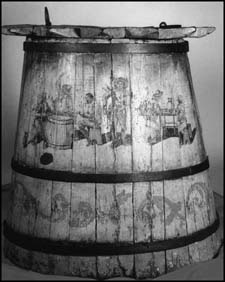

Devised some time prior to the Norman Conquest of 1066 (when it was known by its Latin name cathedra stercoris), this uniquely English form of humiliation was reserved for women who simply could not, or would not, learn how to control their sharp tongues. In the words of the day, it was: ‘a seat of infamy where strumpets and scolds, with bared feet and head, are condemned to abide the jibes of those who pass by’. The chucking stool itself was no more than a wooden arm-chair mounted on two poles, much like an open sedan chair of the eighteenth century. A hole was cut in the bottom of the chair and the victim’s skirts were hoisted up, leaving her exposed rump visible for all to see while she was paraded through the streets of town.

Chucking stool.

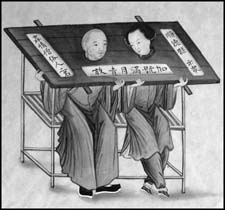

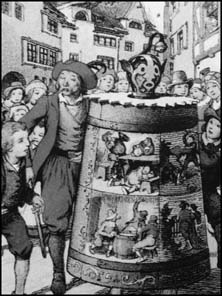

Devised by King James I of England (and quite possibly having been brought into use while James was still reigning in Scotland as James VI) the drunkard’s cloak (occasionally referred to as the ‘barrel pillory’) was a perfect example of letting the punishment fit the crime. Nothing more than a large beer keg with the bottom knocked out and a hole cut into the top large enough for a man’s head to fit through, those convicted of habitual public inebriation were forced to wear the ‘cloak’ whenever they went out in public for a specified period of time. Sometimes additional holes were cut into the sides so the victim could use their hands to help support the barrel’s weight. To prevent the victim from simply stepping out of the thing a locking collar of wood or metal was placed around their neck. While this may seem laughable, anyone who has ever tried to lift a full-sized, 36-gallon wooden cask knows how heavy they are. The drunkard’s cloak was not only a horribly chaffing thing, but its weight could easily tear the muscles connecting the neck to the shoulders. There are records of the cloak remaining in use as late as 1690 when Samuel Pepys, then Secretary of the Royal Navy, mentioned it in his diaries.

Drunkard’s cloak.

Drunkard’s cloak

See ‘Ducking’ in the section ‘Torture by Water’.

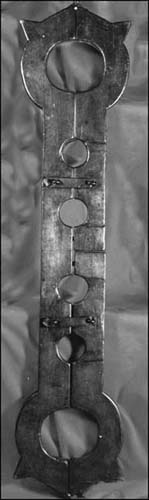

These contraptions served as a sort of portable or mobile pillory (see overleaf). Once the victim was locked into them they could be paraded through the streets whilst being led by a chain and collar around their necks, etc. Sometimes they might even be trapped within these devices before being exiled from a particular city. Similar in that way to the Chinese Cangue discussed above, the victim (or victims) forced to wear one of these contraptions would be completely at the mercy of any passers-by. Furthermore, they would be incapable of feeding themselves and would, therefore, have to rely on the charity and generosity of those same passers-by for food and drink. It seems that this too was a punishment largely reserved for women of a shrewish temperament.

The fiddle.

See ‘Iron Collar’ in the section ‘Torture by Restraint’.

Defined in Webster’s Dictionary as ‘an act of self-abasement, mortification or devotion performed to show sorrow or repentance for sin’, penances were imposed on members of both the clergy and laity who were judged by the Church to be guilty of sins or criminal acts throughout the Middle Ages. Penances for small transgressions could be as mild as a short period of fasting and prayer or as great as taking a pilgrimage to some holy site. In worst case scenarios, such as one case where a Frenchman was found guilty of murdering his infant child, the condemned party had the body of the child chained to his back and was forced to walk all the way to Rome under the strict supervision of a priest and armed guards. Whether or not the man survived is unknown.

Iron fiddle.

Designed to punish those who insisted on disrupting church services, the finger pillory consisted of two boards, hinged together and attached to the wall of a church. One of the boards had four holes drilled through it, spaced to accept a person’s fingers. In the opposite board were four corresponding grooves, or troughs, which closed over the fingers. It was hoped that once the hand of the offender was locked in place they would be a bit more attentive to the Word of God.

Finger pillory.

Pillory.

The pillory is a device wherein the condemned had their head and wrists locked into a wooden frame mounted on a shoulder-height post set up in a public place such as the local market square. Apparently it derived its name from a Greek phrase meaning ‘to look through a door’ – an appropriate description of someone with their head and hands poking through the front of the pillory. The first recorded use of the pillory took place in Classical Greece; the Anglo-Saxons called it the healfang (or half-hang) and it was in constant use throughout the Middle Ages – being codified as a legal form of punishment in England in 1269 by King Henry III – and continuing in use through the early nineteenth century all across Great Britain, Europe and the Americas. The pillory served as a method of punishing those convicted of minor crimes of all manners, be it public drunkenness, brawling, homosexuality, or disorderly conduct. Included in the myriad of petty offences for which a man or woman could be pilloried were, according to an eighteenth-century English statute: ‘those who sell putrid meat, stinking fish, rotting birds, and bread with pieces of iron in it to increase its weight’. In the old Dutch colony of New York a man convicted of stealing cabbages was sent to the pillory with a cabbage tied to his head. While the victim was on public display – a period that could last from a single hour to more than a week – they were subjected to the taunts of their neighbours and, depending upon how offensive their crime was, frequently pelted with rotten vegetables, mud and stones. In some instances, the abuse to which a pilloried individual was subjected was so severe that they were knocked unconscious and ran the risk of strangling to death when the full weight of their bodies came down on their imprisoned neck. One such incident took place at London’s Smithfield Horse Market in the eighteenth century, when two men, James Eagan and James Salmon, were pelted with stones, potatoes, bricks and dead animals.

Double fiddle.

According to an eyewitness account: ‘The blows they received occasioned their heads to swell to an enormous size; and by people hanging to the skirts of their clothes they were nearly strangled’. Eagan died on the spot and Salmon died in prison a short time later. Only a few years after the Eagan/Salmon incident, a homosexual man was pilloried and was pummelled so badly that he: ‘soon grew black in the face and blood issued from his nostrils, his eyes and his ears; the mob nevertheless attacked him with great fury’. When the pillory was unlocked he: ‘Fell down dead on the stand of the instrument’. The pillory could also serve as one part of a larger series of punishments. Some who were pilloried were also whipped and others had their ears nailed to the back-board of the pillory, only to be torn free or cut off when the sentence was concluded.

Donkey – stang.

With so many punishments specifically levied against uncouth women it seems only fair that wife-beating men and tavern brawlers should also be subjected to an equivalent humiliation – hence Riding the Stang. The stang was nothing but a length of log, or a stout pole, which the victim was forced to straddle while he was carried through the streets of his town, accompanied by merrymakers shouting, cat-calling, blowing horns and whistles to call attention to their thoroughly embarrassed captive.

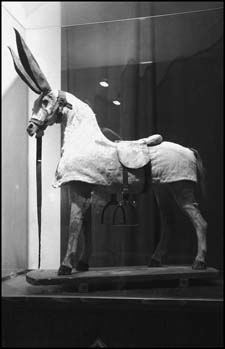

Rocking horse – stang.

Other variations on this form of torture and humiliation were put into play for military punishments, the most extreme of which is sometimes referred to as the Spanish donkey. In this case the ‘stang’ took the form of a wooden horse (sometimes with wheels and sometimes with rockers) and it would either have a spiked seat or perhaps even have been a simple V-shaped wedge. The malefactor would be forced to straddle the ‘horse’ with their arms bound behind their back and they would ride the devilish contraption while others rocked or wheeled them about. Additional torment was frequently obtained though the addition of heavy weights on the ‘rider’s’ feet.

Scold’s bridle.

(See also Branks.) The scold’s bridle, like the ducking stool and the chucking stool, was a device intended specifically to punish sharp-tongued women, and was used throughout Britain and Europe during the Middle Ages. A helmet-like cage made of iron straps, the scold’s bridle was locked over a woman’s head, after which she might be led through the streets of the town and exposed to cat-calls and hoots of derision. To increase the pain, a metal tongue or ball might be forced into the woman’s mouth to gag her screams or curses during the punishment. From the records of Newcastle-upon-Tyne comes this account from 1665:

There he saw one Anne Bridlestone drove through the streets by an officer of the corporation, holding a rope in one hand, the other fastened to an engine called the branks … which was muscled over [her] head and face, with a great gag or tongue of iron forced into her mouth, which forced blood out …

Similar devices were used during seventeenth-century witch trials to keep the accused quiet while their fate was being decided by the court.

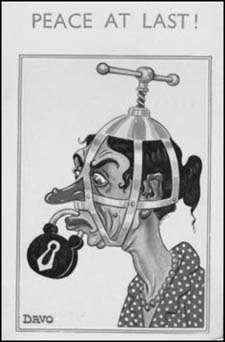

Postcard using scold’s bridle for humorous effect.

A more humane variation of branding practiced in the American Colonies was the custom of having transgressors wear a sign, or placard, that made their shameful behaviour evident to anyone they passed on the street. The most famous such sign is undoubtedly the red letter ‘A’, sewn to Hester Prynne’s dress in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Scarlet Letter. Unlike Hawthorne’s tragic heroine, the real Hester Prynne (who was tried and convicted in New Plymouth Colony in 1671) was not only convicted as an adulteress, but also as a drunkard. Her punishment was to wear both the letters A and D, denoting her double crime. In other instances, the punishment was more fully descriptive. In Boston in 1633, Robert Coles was fined 10s and sentenced to wear a sign with the single word ‘Drunkard’ and in 1650 a Connecticut man found guilty of insulting ministers and disrupting church services was forced to wear a sign reading ‘Open and Obstinate Condemner of God’s Holy Ordinances’. Similarly, Ann Boulder had to wear a sign stating that she was a ‘Public Destroyer of the Peace’. Presumably, if the condemned failed to wear the sign as instructed they would be charged with more serious offences or, at the very least, given a harsher punishment for the original. This idea of ‘naming and shaming’ is one which is finding favour among modern contemporary exponents for crimes ranging from shoplifting to child sex offences.

A brank in Lancaster Castle.

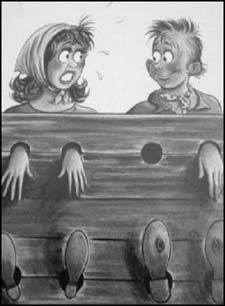

A postcard using punishment of stocks for humorous effect.

Roughly similar in structure and purpose to the pillory, the stocks were a hinged, wooden restraint into which a person’s ankles were locked. Also like the pillory, the stocks were of ancient origin (at least dating back to the Anglo-Saxon period) and located in public so the condemned was exposed to constant humiliation and abuse – an indication that they were not used to punish violent criminals, but to teach people a lesson in good manners and honesty. In an English law of 1426, it states that vagrants were to be locked in the stocks for a period of three days and nights and given only bread and water. A record dating from the mid-1500s tells us that in London ‘four women were set in the stocks all night till their husbands did come to fetch them’ and in eighteenth-century Boston, Massachusetts, Edward Palmer was fined and sentenced to spend one hour in the stocks for stealing a plank of wood. The stocks were less physically damaging than the pillory, but to make sure the victim was not too comfortable, they were often forced to sit on the edge of a narrow board while they endured their sentence. The early medieval French added another distressing dimension to the time spent in the stocks; the bottoms of the victim’s feet were doused with saltwater and a goat was allowed to lick them. It may have been hysterical for those watching but a goat’s tongue is as rough as sandpaper and after a very few minutes the pain became excruciating. The humiliation associated with being put in the stocks remains with us in the phrase, ‘being made a laughing stock’.

Stocks.