The word torture is used so often and so inappropriately that it seems necessary to define exactly what it means before entering into any serious investigation of its uses; or more specifically to extricate the term from the confused jumble of multiple definitions in order to determine precisely what we mean by ‘torture’. Contrary to popular belief all forms of punishment, even when it involves physical abuse, do not qualify as torture. The thirteenth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica describes torture as follows: ‘Torture (from Latin “torquere”, to twist), the general name for innumerable modes of inflicting pain which have been from time to time devised by the perverted ingenuity of man, and especially for those employed in a legal aspect by the civilised nations of antiquity and modern Europe.’ From this point of view, torture was always inflicted for one of two purposes:

(1) as a means of eliciting evidence from a witness or from an accused person either before or after condemnation;

(2) as a part of punishment.

The second was the earlier use, its functions as a means of evidence arising when rules were gradually formulated by the experience of legal experts. Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary describes it more briefly, but more succinctly, in this manner:

1. The infliction of intense pain (as from burning, crushing or wounding) to punish, coerce or afford sadistic pleasure.

2. An anguish of body or mind.

3. To punish or coerce by inflicting excruciating pain.

4. To cause intense suffering, to torment.

Using these basic premises as a starting point, we can immediately say that before physical brutality can qualify as torture it must be inflicted with very specific goals in mind. If a street gang attacks, beats and systematically abuses someone they are not, strictly speaking, torturing their victim. They are certainly assaulting them and may cause grievous bodily harm, but because they are not acting under any kind of governmental, military or judicial authority the assault is not technically torture. On the other hand, a gang of revolutionary guerrilla fighters who commit the same atrocities are, in fact, committing torture. The main difference then between a simple act of barbarism and full-blown torture is the influence of a higher, sanctioning authority. Inherent, but seldom stated, in this definition is the implication that when torture is carried out at the behest of governmental authority it is somehow justified. By bringing a legal sanction into the equation those involved in ordering or administering torture provide themselves with the advantage of removing the taint of personal guilt: ‘I was only following orders’.

As we shall see time and time again, those governments that have sanctioned the use of torture tend to be either weak and fearful (as in the case of most early, primitive societies and modern, third world dictatorships), or paranoid. In the later case there is almost always the belief, either sincerely held or merely a cynical ploy to keep the masses in line, that there is some massive conspiracy at work which is bent on the destruction of the ‘system’ and that it must be stopped before society is overthrown. Such claims of imminent destruction are always a good way to keep the population in a constant state of fear and thereby make them easier to control. It also provides a convenient means to make the leader popular; first he institutes a climate of fear by describing this vague, often nameless threat, and then sets out to destroy that threat by arresting, torturing and executing as many of the ‘conspirators’ as possible. Naturally the threat can never truly be eliminated; either because it never existed in the first place or because if the ‘enemy’ ceased to exist the leader might lose his grip on power.

In its earliest form, however, torture – in some greater or lesser form, as befits the crime – was usually practiced as a means of punishing actual wrongdoers. In a primitive world, where all life was short, brutish and cruel, we could hardly expect legal or penal punishment to be any different. When a criminal, or transgressor against the prevailing moral code, was publicly whipped, crucified, or otherwise horribly killed or maimed, it provided a graphic example that the law was being upheld, society was being kept safe and that good, law abiding people could sleep safe in their beds. Such graphic examples of the law taking its due course always pleased the mob, giving them a nice comforting sense as to the ‘rightness’ of things. It also provided a form of cheap entertainment and, unless the leader was unusually stupid, offered a convenient way of doing away with political enemies in a way that sent out a clear message to anyone else who might decide to voice opposition to the powers that be.

Over the millennia, thousands of civilisations have risen and fallen, but the use of torture and the reasoning behind it, remain pretty much constant. The earliest use of torture, that of punishment, tended to be psychologically unsophisticated. The party in question, or the conquered group, was adjudged guilty and then taken out and punished. But as time went on, and as the motive behind torture evolved from simple punishment to the need to extract information, the approach to the process of torture evolved. Victims were first taken to the torture chamber and shown the tools of their forthcoming anguish. To get the victim’s attention, the entire process was described in lurid detail. Then they were sent back to their cell and given some time to think things over. Unless the poor wretch had no more imagination than a cow, the mere contemplation of what was about to happen to them was often enough to make them spill everything they knew and a whole lot they didn’t know. Sometimes, however, the victim was unusually strong-willed or it had already been decided that they were going to be tortured no matter what they said.

In 1307 King Phillip IV of France (with the whole-hearted support of the Pope) ordered the mass arrest of the Knights Templar on charges of heresy. Did he really believe them to be heretics? Probably not. Did he owe them huge sums of money that he had no intention of repaying? Absolutely, but it would not have looked good if he had been honest about his motives. Instead, Phillip had thousands of Templars rounded up, thrown into prison, put to the rack, roped, starved and beaten to within an inch of their lives. Eventually they confessed to the most absurd charges imaginable. Once in possession of their confessions, Phillip was free to convict, sentence and burn them at the stake. Then he confiscated their land and property. The fact that nearly all of the Templars later refuted their forced confessions made no difference. This single example of confessions forced through pain is only one of hundreds we will examine in this book but it serves as a workable, introductory illustration to both the advantages and drawbacks of torture. Torture can always be used to extract a confession or other information – almost anyone will confess to nearly anything if they think it is going to make the pain stop. Conversely, torture cannot be used to establish innocence – possibly because it would be a sorry sort of torture master who mutilated his victims while repeatedly asking ‘Have you been a good boy?’

The point we are making is that torture has only one conceivable end – to extract the information, or punishment, demanded by the system. In the case of obtaining information, the torture will continue until the victim has provided whatever information they are instructed to provide or dies. It does not take a genius to realise that this is an ultimately flawed process. Indeed, if what the inquisitors are really looking for is the truth, then torture is demonstrably counter-productive. The sad truth of this fact has been realised and admitted to by law-givers, philosophers and clerics since time immemorial and still, by and large, they approved of, and used, torture to extract confessions as well as inflict punishment. Why? Because the true object of torture is not to discover the truth but to secure a conviction; and therein lies its greatest limitation. A person under torture will, sooner or later, confess but this is no assurance that a) they actually committed the crime and b) if they did not, and an actual crime has been committed, then the real culprit is still at large. Occasionally, someone being subjected to torture has been able to overcome their terror and pain long enough to throw this fact back in the face of their persecutor.

During the height of the Spanish Inquisition in the sixteenth century, a Portuguese woman named Maria de Coceicao was arrested on charges of heresy and sent to the torture chamber where she was racked. To avoid having her arms and legs ripped from their sockets, Senora Coceicao immediately confessed but as soon as she was released from the rack she refuted her confession. A second turn on the rack brought an identical response. It was a familiar pattern: Confess anything to make the pain stop and then recant when released. In her case, Coceicao was both clever enough, and brave enough, to tell her tormentors: ‘As soon as I am released from the rack I shall deny whatever was extorted from me by pain.’ Maria de Coceicao was far more lucky than tens of thousands of other victims of the Spanish Inquisition. She was publicly flogged and sentenced to ten years in exile but the courage of her convictions had saved her from being burned at the stake. So, had she brought some revelation to the local inquisitor? Probably not. We can readily assume he already knew that torture did not discover the truth. So why did he and hundreds of others employ it over thousands of years of history? Because it was part of a workable system that kept the established powers securely in their place and the peasants safely in theirs.

Curiously, since the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, England has considered the use of torture for the purpose of extracting information or a confession to be illegal. We say ‘curiously’ because throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, England was as guilty of torturing its subjects as any other country in Europe – they simply never admitted this small fact to themselves. In 1583, Sir Thomas Smith, then serving as Secretary of State under Queen Elizabeth I, wrote:

Torment or question, which is used by the order of the civil law and custom of other countries, to put a malefactor to excessive pain, to make him confess of himself, or of his fellows or accomplices, is not used in England … [as] the nature of our country is free … and beatings, servitude, servile torment and punishment it will not abide.

Sir Thomas wrote this – undoubtedly in all honesty – despite the fact that at no time, nor in any place, in history has torture been more commonly in use than in sixteenth-century England. So how did it come to pass that a long string of English monarchs, and their governments, tortured their subjects while steadfastly denying that they did so? Simple. Torture was only allowed when the reigning monarch approved of it and since monarchs were technically above the law, their word superseded any and all written laws. An interesting example of how one man tried to overcome this technical ‘glitch’ in English law, and at the same time foil his torturer, took place during the reign of King Charles I (1625–49).

In April, 1628, John Felton stabbed the Duke of Buckingham to death, was arrested and, as the English politely put it, ‘put to the question’. There was no doubt of Felton’s guilt; he committed the act in full view of a large crowd which subdued him after the murder and held him until he could be formally arrested. The question facing the court was whether or not Felton had acted alone or as part of a larger conspiracy. As was usual in such cases, the court assumed that while Felton had acted alone in carrying out the deed, he must have had help in the planning. During his initial questioning by the Earl of Dorset, Felton was threatened with the rack unless he named his accomplices. Felton then told the Earl: ‘I do not believe, my Lord, that it is the King’s wish for he is a just and gracious prince and will not have his subjects to be tortured against the law.’ Then, with more courage than most people could have mustered in his tenuous situation, he added: ‘Yet this I must tell you, by the way, that if I be put upon the rack, I will accuse you, my Lord Dorset, and none but yourself as my accomplice.’ Obviously Dorset was faced with a terrifying dilemma; confessions under torture were accepted as absolute truth and he had no desire to join Felton in his meeting with the executioner. Still, he approached King Charles who immediately grasped the situation and ordered Felton to be ‘tortured to the furthest extent allowed by law’. Since His Majesty had not specifically approved of torture, the matter was referred to a panel of twelve jurists who ruled: ‘Felton ought not by the law to be tortured on the rack, for no such punishment is known or allowed by our law’. Felton had pointed out one of the great fallacies of life in Merry Old England and saved himself from a horrible torture but it did not save his life. On 28 November 1628 he was hanged for his crime.

Despite the fact that it was useless in discovering the truth, torture nearly always loosened people’s tongues. The side effect this process may have had on a person accused of committing a criminal act, or even a perfectly innocent bystander who might have information concerning some crime, was completely irrelevant. It is results that count. What the ancient and medieval torture masters may have been unaware of is how the psychology behind the process of torture actually works. As we have already seen, one of the first steps in convincing a prospective victim to talk is to show them the instruments with which they will be tormented. This, along with the actual process of torture, and the fact that the presiding authority – be it a civil judge or a clergyman of the Inquisition – always remains one step removed from the application of torture, have become recognised as integral parts of what has become known as the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’. Named for a hostage situation which took place in Stockholm, Sweden in 1973, when two bank robbers held four people hostage for a period of six days, the Stockholm Syndrome has identified the process by which an individual’s will is broken down to the point whereby the victims come to cooperate with their captors. This process involves two distinct steps, the first of which rearranges the normal mind-set of the prisoner as follows:

The captive comes to believe that escape is impossible and they are made to believe – rightly or wrongly – that their survival depends on the whims of their captors.

The captor gains the confidence of their captive by showing them small, often irrelevant acts of kindness.

The prisoner is kept isolated from all contact with the outside world.

Once the victim has been sufficiently disoriented and realises that their life depends on the good graces of their tormentor, they are subjected to the next level of the interrogation process; the one intended to make them confess or provide whatever information their captors desire.

The victim is subjected to physical (or sometimes sexual) abuse, thus making them feel still more vulnerable.

The captive is deprived of a proper sense of time and place; usually by keeping them in a dark dungeon or cell.

The victim is deprived of privacy. Their guards can walk in on them at any moment for whatever reason.

The prisoner is only fed and given water when, and if, their captor feels like it.

Thus having lost all sense of control over their own life, the prisoner is kept in these conditions and tortured at unpredictable intervals. Always standing off to one side, ready to listen to their ‘confession’ is the person who controls both the prisoner and the torture masters. This individual is not only the source of all pain, but also the only means through which the pain can be made to stop. As soon as the victim is willing to answer the inquisitor’s questions, the torture master will be told to stop inflicting pain.

By slowly building on this process, from capture through imprisonment and being shown the process by which a person’s body will be slowly crushed, burned, boiled or torn to shreds, it is often unnecessary to actually subject the victim to torture. Their fear does what it might, theoretically, be impossible for the torture master to do. A personal account of how this process works comes to us from the journal of Fr. John Gerard, a Jesuit priest who was arrested as a subversive in 1605 in connection with Guy Fawkes’ failed gunpowder plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament and kill the entire government of England and the royal family of King James I. It was not Gerard’s first brush with the law; in 1597 he had been arrested on similar charges during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, so he was already familiar with the official interrogation process. His description of how suspects were first encouraged to tell what they knew is one of the best surviving first-hand accounts of the torture chamber in the Tower of London during that era.

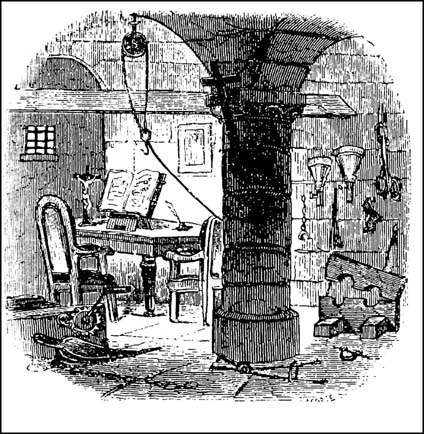

This image depicts the interior of a late medieval torture chamber. Tortures of the rack, the pulley, the stocks, the funnel, and the bilboes are visible among other objects. This is probably intended to depict an Inquisition chamber owing to the two prominent crucifixes on display and the ledger for recording confessions.

We went to the torture room in a kind of solemn procession, the guards walking ahead with lighted candles. The chamber was underground and dark, particularly near the entrance. It was a vast shadowy place and every device and instrument of human torture was there. They pointed out some of them to me and said that I [w]ould have to taste of them. Then they asked me again if I would confess. ‘I cannot’, I said.

For his obstinacy, Father Gerard was racked and tortured but he managed to escape and make his way to the safety of the continent.

Some implements of torture. Both commonplace and exotic, these inert objects seem impotent in their state of disuse. Clockwise from top left we can see what appear to be a flail or scourge, a ‘cat’s paw’, a chastity belt (upside down) a dismembering axe, funnels, rope, shackles, pincers, knee splitter, shears, a spiked ball and chain, galley shackles, and a spiked belt or barbed flail.

Only five years after Father Gerard’s adventure, King Henry IV of France was murdered by a man named François Ravaillac. Like his predecessors, Felton and Gerard, Ravaillac was automatically assumed to be a part of a larger conspiracy. In this case, however, Ravaillac was tried and sentenced to death before the names of his suspected accomplices were tortured out of him. As he was already condemned to death, he had no hope that naming his associates would spare him from execution. Lacking any incentive to speak, the only reasonable course of action was to subject him to enough pain to loosen his tongue. Despite swearing before the court that he had acted alone, Ravaillac was taken to the torture chamber and subjected to a torture known as the ‘brodequin’ – an excruciating procedure where heavy wooden wedges were driven into the muscles of the legs with mallets. According to the records of the court, when the second wedge was driven into place, Ravaillac screamed: ‘I am a sinner, I know no more than I have declared, by the oath I have taken, and by the truth I owe to God and the court: all I have said was to the little Franciscan [Priest, in the confessional], which I have already declared… I beseech the court not to drive my soul to despair.’ The torture continued, but Ravaillac steadfastly insisted he had acted alone. Finally, too crippled to walk to his execution, François Ravaillac was put to death for the crime of regicide.

This scene depicts the torture of peine forte et dure. The victim is forced to lie across a sharp rigid edge which is placed just below his shoulder blades. A board is then placed upon his chest and more and more weight is added until he tells his torturers what they wish to hear. Note also the chap in the background with his feet in the stocks or inversion chair – perhaps awaiting his turn under the crushing weights.

Once the process of actual, physical torture had begun, only those with an unimaginably strong will, the deranged mind of a fanatic, or a masochist who enjoyed becoming a martyr to their particular cause, could prevent themselves from admitting to anything the inquisitor wanted to hear. In societies where torture was routine, everyone knew that if arrested they would, sooner or later, confess. When Baron Scanaw was arrested in the mid-sixteenth century, in Bohemia, on charges of heresy, he was told that if he did not willingly offer up the names of his confederates he would be racked until he decided to talk. When the guards came to haul Scanaw to the torture chamber they found that he had cut out his own tongue. Beside his unconscious body was a note which read: ‘I did this extraordinary action because I would not, by any means, or any tortures, be brought to accuse myself, or others, as I might, through the excruciating torments of the rack, be impelled to utter falsehoods.’ The brave Scanaw might have saved his friends from meeting a similar fate, but he could not save himself. Since he could no longer talk, he was simply racked to death.

One of the simplest, and most bizarre, forms of torture designed specifically to induce a suspect to talk was that of ‘pressing’. According to medieval and renaissance law, a suspect could only be properly tried if they openly confessed to their crime. Instances where prisoners refused to enter a plea were particularly galling because only once they admitted their guilt could their property be confiscated by the state. If they simply refused to plea, there was always enough possibility of innocence that their property would pass on to their legitimate heir. For the government to get as much satisfaction (and profit) as possible out of executing an enemy, they must confess their guilt. To this end the practice of pressing was introduced. It was extremely simple. A subject was laid on the floor of their cell or the torture chamber, a door was laid on top of them and more and more stones (or other weights) were piled on top of the door. In less than a minute breathing became difficult, then nearly impossible. As this was specifically a torture of inducement, the weight was increased very slowly: if the victim died before confessing, their estate remained in the family. Smothering is a terrible death and only the strongest willed could withstand both the crushing weight, the inability to breathe and the sure knowledge that all they had to do to make it all go away was talk. The last recorded case of pressing to extract a confession took place during the Salem, Massachusetts witch trials in 1692; in that case, like so many others before it, the victim chose not to confess to a crime of which they were wholly innocent.

No matter how effective, or ineffectual, torture might be at making a person confess their guilt or betray their accomplices, real or imagined, torture when used as a means of punishment was guaranteed 100 per cent effective. It may not have deterred other criminals, slowed a constantly rising crime rate or even reformed the person being punished, but it was completely effective in the sense that punishment had been extracted as prescribed by law and, in almost every case, the punishment had been carried out in full view of a public who demanded constant reassurance that their government was ‘getting tough on crime’.

Defining precisely which forms of punishment qualify as torture, and which do not, is slightly more problematic than when dealing with torture as a means of extracting a confession or information. Any time information is forcibly extracted from a prisoner there is a high probability that some form of torture has been involved because the innocent have no information to give and the guilty are unlikely to willingly offer whatever information they possess. Punishment, on the other hand, by its very nature, implies that the convict is being disciplined to some greater, or lesser, extent; the degree of punishment being determined by the severity of the crime. No matter what the crime, when the rules of the society in question have been broken, some form of retribution must be exacted if the law of the land is to be satisfied and the public is going to be reassured that their government is doing its job. Failure to follow this simple concept would lead to a state of chaos and, inevitably, to the collapse of society.

So when does punishment become torture? Undoubtedly, when a convict is executed slowly and in an excruciatingly painful manner, it is safe to say that they are being tortured to death. Whether lesser punishments can be legitimately considered torture can only be judged by the prevailing mores of the society. In the ancient world, where life was harsh and brutal even in its quietest moments, there were only three primary kinds of punishments: whippings, imposed for minor crimes; ‘an eye for an eye’ retributionary punishments for more serious, but not capital, crimes and finally, at the top of the list, execution. Since petty crime is always more prevalent than serious crime, whippings were the most common form of punishment meted out in almost all ancient societies. Whether the whipping was inflicted with a stick, a heavy rod, a simple leather whip or a cat-o-nine tails with sharp slivers of metal braided into the thongs, were determined by the seriousness of the crime and how brutal the standards of the society were.

Here we see a public flogging taking place. This would have been a fairly commonplace scene throughout Europe until well into the eighteenth century. The victim here (apparently a woman) is being flogged with bundles of sticks (although being hung by the wrists is certainly unpleasant enough). It could well be that the man flogging her is in fact her husband and that he was legally entitled to this recourse for her shrewish behaviour or infidelity, but only if the flogging was administered publicly.

Hand-in-hand with the concept of whippings and other minor, public punishments was the concept of shame and humiliation which inevitably accompanied the punishment. The whole concept of shame has virtually disappeared from modern society, due largely to the anonymity of overpopulated cities and the breakdown of community and family life. Things were different in the past. Small communities, where everyone knows everyone else and knows all about their business, are a perfect platform for imposing soul-crushing levels of shame. In the tiny, isolated communities that existed from the dawn of civilization through the late eighteenth century, when friends, neighbours and family refuse to talk to, or do business with, someone who had stepped beyond the bounds of acceptable behaviour, it was a truly shattering experience. Add to this the fact that the offender had been whipped, or otherwise punished, in full view of the entire community and they would have probably been more than happy to exchange the experience for a few months in a nice gloomy prison where they could suffer in private.

As was true with minor crimes, the punishment for more serious offences was determined largely by how civilised, or how barbaric, the individual society happened to be. The time period in which the society existed had surprisingly little to do with how ‘civilised’ the punishments were. As we shall discover in the next section of this book, ancient Egypt was fairly civilised but 4,000 or 5,000 years later the punishments imposed during the Dark Ages and early medieval period were unbelievably horrific. Branding, dismemberment, scalping, ripping tongues out by their roots, throwing people from cliffs, skinning them alive and ripping their entrails from their still-living bodies were all commonly imposed punishments used in early European societies. So why did society seemingly deteriorate? In reality, it did not deteriorate at all. As we saw earlier, stable societies are less likely to fall victim to the paranoia that creates brutal punishments than are unstable societies. The Egyptians had a stable, well-organised society ruled by an ancient system of royalty and priests who were not in constant fear of being toppled. The societies of the dark and early Middle Ages, on the other hand, were tremendously unstable and tended to be led by whichever warrior had the biggest sword at the time. To such fearful leaders every lawbreaker offered a perfect opportunity to set an unmistakable example. As late as the Renaissance, punishment throughout Europe was at least as brutal as it had been under the yoke of the Roman Empire 1,500 years earlier. A single example should serve to illustrate this point.

These ankle restraints are from the eighteenth or nineteenth century when somewhat more humanitarian concerns affected attitudes towards imprisonment or incarceration. These have obviously been designed for prolonged use as they have been shaped to make them more comfortable and less irritating, and yet maintain restraint.

During the late tenth century, a bell maker from Winchester, England, named Teothic was arrested and convicted of what the church records (where the case is recorded) only refer to as ‘a slight offence’. Under the rules of Anglo-Saxon England – which was one of the more stable societies in northern Europe at the time – the wretched Teothic was shackled and hung up by his hands and feet. The following morning he was taken down long enough to be whipped unmercifully before again being hung up like a side of beef. How long this horrific punishment might have continued we do not know because somehow Teothic escaped captivity and took sanctuary at a local monastery.

When the crime is more serious than the one poor Teothic was convicted of – serious enough to demand the death of the prisoner, and bear in mind that as late as the eighteenth century, stealing a loaf of bread was a capital offence – the most unspeakable tortures can be justified under the concept that once a person has committed a serious crime they surrender every protection and comfort society extends to its law-abiding citizens. Once publicly placed outside the parameters of society, the malefactor could be legally dealt with – either swiftly and cleanly or in the most unspeakable manner imaginable. If his end was to come swiftly – relatively speaking – the most popular form of execution has always been by hanging.

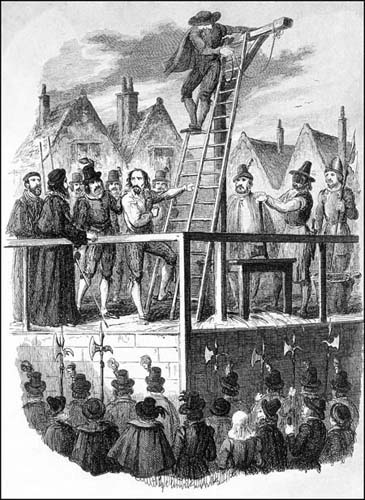

This engraving of a public hanging serves to illustrate what public spectacles these executions grew to be. Though we might assume by the presence of the masked executioner with the axe on the right, that this was not going to be a simple death by strangulation, but was, more likely, to have been a case of hanging, drawing and quartering as described later in this book.

Despite the fact that until well into the nineteenth century – when a trapdoor was installed in the scaffold allowing the condemned to be ‘dropped’ to a nearly instantaneous death – hangings were carried out by placing a noose around the prisoner’s neck and hoisting him into the air where he dangled, kicked and choked himself to death over the next ten to twenty minutes, hanging has never been considered torture. So if hanging was cheap, easy, relatively quick and never considered a form of torture, why were so many strange, bloody and painful executions devised for so many different crimes? Before answering this question, it might be well to recount the more popular forms of execution – and the concomitant crimes – still in use as late as the sixteenth century. The following list comes from 1578 when it was compiled by the English chronicler, Ralph Hollinshed.

If a woman poisons her husband she is burned alive; if a servant kills his master he is to be executed for petty treason; he that poisons a man is to be boiled to death in water or [molten] lead, even if the party did not die from the attempted poisoning; in cases of murder all the accessories [before and after the fact] are to suffer the pain of death. Trespass is punished by the cutting [off] of one or both ears … Sheep thieves are to have both hands cut off. Heretics are burned alive [at the stake].

Not included on this list are simple hangings; beheading in cases where noblemen were convicted of treason and hanging, drawing and quartering imposed on commoners found guilty of the same offence. Burning at the stake – that ever-popular horror – took several forms. When the person in question had been convicted of heresy, if they recanted their sin they were usually strangled to death, or hanged, before being consigned to the flames. If they clung to their heretical belief they were condemned to be slowly roasted alive. Simple cases of murder would lead a man to the gallows but a woman was more likely to be burnt. Why? Because the corpse was routinely stripped naked and left to twist in the wind after the execution and it was considered disgraceful to expose a woman’s bare body to the curious stares of the public.

In this illustration by Francisco Goya we see an execution by garrotte. This method rose to popularity in Spain during the years of the Inquisition and continued in use as late as the eighteenth century. The condemned is sat in a chair with a strap about his neck. The executioner slowly tightens the strap by way of a mechanism on the back of the ‘chair’ and slowly strangles the condemned to death. In some versions we find the presence of a spike at the back of the neck designed to pierce and sever the cervical vertebra thereby paralyzing the victim through the process.

Before we condemn all the long-lost kings, princes, judges and church-men who imposed such horrific tortures as barbarians, it is well to remember that, unless a nation had been overrun by a foreign power, governments generally keep their hold on power by pandering to the needs, beliefs and tastes of their people. Torture, at least when carried out in public, and public executions were not only accepted by the general populace but demanded by them. Any king who denied his subjects the thrill of an occasional flogging or hanging, risked being toppled from his throne by one of his fellow noblemen who knew how to keep the masses happy.

So far we have only considered torture as a means of punishment, or coercion, judicially inflicted by governments on their more disobedient subjects or hapless victims. Before moving on to a more complete history of torture we should look at another aspect which sometimes creeps into the already horrific annals of torture; the overall mind-set of those involved in the process at whatever remove. That is to say, the preconceptions and expectations of the individual being tortured, the person or persons inflicting the torture and, finally, on the public, which so often gathered to enjoy the spectacle of another human being subjected to unimaginable torment.

Since humanity’s earliest realization that there are greater powers in the universe than our own little selves, humans have had the sneaking suspicion that the gods – and later even God, Himself – demanded sacrifices in the form of human suffering. At first it was a way to make the gods take away the thunder. Next it was a way to ensure that the crops grew, or the upcoming battle was won and last of all it just became a way to make the gods happy. In many primitive societies, this sacrificial suffering took the form of human sacrifice – the Aztecs ripped out the hearts of prisoners of war by the thousands. In more advanced societies the sacrificial pain became a more personal matter: ‘If I have committed a wrong, then I must be the one to pay for it’. This concept of accepting personal responsibility may have originated among the ancient Egyptians. Records show that Egyptian priests in the service of the goddess Isis flagellated themselves during specific festivals. Similarly painful self-punishments have been practiced by Hindu holy men who inflict a staggering array of painful experiences on themselves as a demonstration of their faith in their gods and control over their own bodies. It is not surprising then, to find that early Christians engaged in a variety of spiritually cleansing acts; all of which were designed to show the penitent’s remorse, their desire for forgiveness and submission to the power of God.

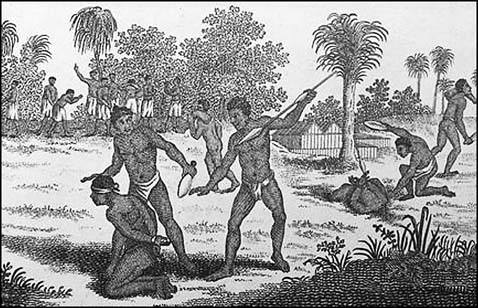

This is a European depiction of methods of execution among tribes in Guinea. The kneeling victim is presumably a prisoner of war and is either going to be dispatched by the spear or the primitive axe/sword/club held by the second tribesman. In the background we can see a decapitated body, but it is uncertain whether this was the means of execution or a result of butchering. You may note that the decapitated man’s legs are missing and are being carried away by two other tribesmen – presumably for dinner.

In the early Christian Church the only universal punishment was excommunication – that is to say being expelled from the body of the Church. Slowly, an elaborate system of penances was devised so as to allow a person to cleanse themselves of their sin while remaining a member of the Church. Among the more common methods of penance was fasting, prayer and going on pilgrimage to some holy place. The length and severity of the penance naturally depended on the severity of the transgression. There was yet another form of penance which rapidly became the most common form of punishment among those in ecclesiastic orders (monks, priests and nuns) who ran afoul of the rules of their order or the precepts of Holy Mother Church – flogging. By the end of the ninth century the practice of flagellation had become such a common means of atoning for sins and transgressions that rules had been laid down as to precisely how a monk, or nun, was to be whipped, how many lashes were appropriate for which transgression and what other penances might go along with the flogging. When flagellation was to take place, the penitent was to remove all of their clothes prior to being disciplined, and the punishment was to be carried out before the entire assembled company of their house. The severity of the punishment varied vastly depending upon the seriousness of the offence, but the intent behind ritualizing the punishment was the same in all cases – by witnessing the suffering of their fellow cleric, the other members of the community would be taught a lesson in humility and discipline and, unless they were complete dullards, understood the fact that life is filled with suffering, most of which we have brought upon ourselves through our sinful ways. Medieval Christian clerics also tended to view everything in life as an allegory for something else. Hence, when they witnessed one of their brothers or sisters being whipped they were likely to think about the pain Jesus suffered on the cross and how much He sacrificed to save the souls of a sinful humanity. Being reminded of such a thing was good even if a member of the community had to suffer to make the point clear.

The problem with the practice of dwelling on the suffering of Jesus, and its concomitant reflection in inflicting pain on members of the religious community, was that pain itself – either inflicting it or experiencing it – eventually came to be seen as an act of faith. Suffering – as an act of redemption – became a religious act. While this fact may never have been actively understood, it became so tacitly accepted that even the most revered saints, such as St Francis of Assisi (now best remembered as a man so holy that he could communicate with animals) spent much of his time flogging himself to a bloody pulp and advocating the same act for others who would follow in his footsteps. Obviously, when men as revered as St Francis indulged in self-inflicted pain, others came to believe that whippings were good for the soul. The great mass of medieval people never joined monasteries or convents, but this was an age of faith and nearly everyone desired to be as pious as those who devoted their lives to God. Consequently, accepting a good flogging from the local priest, or inflicting self-flagellation, became nearly as common a means of expiating one’s sins as going on pilgrimage or fasting.

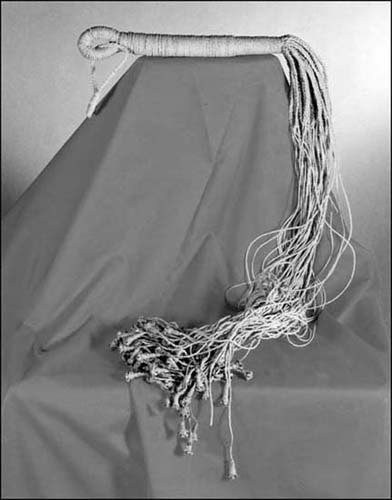

Whips, flails, floggers, quirts, cat-o-nine tails, etc. all come in a variety of shapes, sizes, types and severities. This one, while it may have been intended for use as corporal or judicial punishment, is of a type which we would categorize as a ‘scourge’. This may well have been made by an overly devout flagellant for the purposes of self-mortification. It was believed that through their suffering they would find redemption – both for themselves and the rest of humanity.

In 1424, an Englishman named John Florence was accused of heresy and given the choice of being excommunicated or to submit to an appro-priate punishment. A true heretic would undoubtedly have chosen excommunication but Florence presented himself for discipline. On three successive Sundays, he was whipped in front of his congregation at Norwich Parish Church and suffered the same punishment at a neighbouring church. Such punishment was not reserved for the common man; even the most exalted members of lay society were willing to suffer the pains of the lash if it would remove the stain of whatever sin they might have committed. The most famous case may well be that of England’s King Henry II. In the year 1170, Henry had, either by intent or by saying the wrong thing at the wrong time, caused the murder of his good friend, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket. Outraged by Becket’s killing, the pope excommunicated King Henry and told him to think things over for a while and get back to him. Knowing that an excommunicated king could never hold the throne – and probably truly remorseful over Becket’s brutal death – Henry walked barefoot, in the middle of winter, from London to Canterbury. There, he submitted himself to a monumental flogging. Each of the five prelates of Canterbury Cathedral administered five lashes to the King’s bare back and then each of the eighty monks gave him three more lashes. After receiving 265 lashes, the King was dressed in sackcloth, anointed with ashes and led to the altar of Canterbury Cathedral (the place where Becket had been murdered) where he knelt in prayer for an entire day and night.

Considering how socially acceptable and wide-spread the concept of flagellation as a means of penance had become, it is hardly surprising to learn that entire fraternities grew up to cater to those who chose this painful form of personal redemption.

In 1259, a plague broke out in Italy. With the country already wracked by internal wars and political corruption, society nearly broke down and itinerant priests and monks began warning that the end of the world was coming and that the arrival of the Antichrist was nigh. Terrified, one of the flagellant fraternities, known as the ‘Disciplinarians of Jesus Christ’, began wandering across the countryside, whipping themselves to expiate the sins of the world, and picking up masses of followers in every town and village they passed through. Men, women and even children joined their ranks and within months, parades of up to 10,000 bleeding bodies were stumbling down the roadways of Italy; chanting hymns and canticles, their faces covered against the shame of the world and their backs bared to accommodate the self-administered floggings. The sight was so terrifying that entire warring armies laid down their weapons and stood aside to let the sad procession make its way unmolested.

This might have been seen as an isolated incidence of mass hysteria except for the fact that almost 100 years later, in 1447, the Black Plague broke out in Europe. In a matter of two-and-a-half years it wiped out nearly one third of the population. As the plague spread – and with it the belief that the disease was God’s punishment for mankind’s sins – an army of flagellants reappeared. The events of a century earlier were repeated but this time the flagellants had assumed a truly militant attitude. Where priests spoke out against their self-abuse, they broke into church services. When they wandered through Jewish ghettos they persecuted the Jews. In a matter of months, the flagellants spread out of Italy and into Switzerland, Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, the German states, Denmark, Holland and Flanders and the farther they spread the more aggressive they became. Terrified, in 1349, Pope Clement VI outlawed the flagellant sects, insisting that such extreme actions were nothing less than heresy.

Eventually the Black Death died out and with it so did the flagellants. What no one at the time could have understood is that pain, like drugs or alcohol, can become addictive; particularly when imposed under conditions of great emotional excitement or stress. The more troubled the times, the greater the need for demonstrative emotional release. Amid the terror of war and plagues, the flagellants, who purportedly sought to mitigate mankind’s sin, had embraced a new sin – sado-masochism (though that was a term which would not come in to existence for centuries). The same condition existed where corporal floggings were administered in the sexually repressed atmosphere of monasteries and convents; the whippings – either administering them or accepting them – became a substitute for sexual gratification.

This particular aspect of punishment and torture – the concept of inflicting, or accepting, pain because it provided emotional or sexual gratification is too intimately involved with the overall concept of this book not to bear at least a brief investigation. In the instances described above – that of corporal punishment in the form of religious scourging – it is self-evident that the pleasure/pain syndrome could, and undoubtedly often did, become confused. In a more general context, the infliction of pain on a helpless victim may not have been intended to be a sexually or emotionally exciting experience, but torture master is precisely the type of job that would appeal to someone of a depraved disposition. Likewise, those who oversaw the administration of such torture, be they judges, clerics or other authority figures, were in a perfect position to experience vicarious thrills by watching someone have the flesh flayed from their back or their arms and legs ripped from their sockets. Examples of men who quite obviously enjoyed their work will not be difficult to find in the next section of this book. As is true with most addictions, those who become addicted to inflicting – or in the case of the flagellants, receiving – pain, eventually develop a tolerance to their accustomed jolt and require ever stronger doses of the medicine. This may well account for the increasing levels of terror imposed by particular kings, dictators, jurists, or clerics, particularly those like Thomas de Torquemada, the first Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition.

Evidence that the Spanish Inquisition attracted far more sadists than religious fanatics is evident when we look at the latitude which the Inquisition allowed the guards in administering whippings to prisoners, even when they were not immediately being subjected to torture. If a prisoner was heard to speak (unless they were at prayer) they were whipped; if they sang they were whipped; if they spoke to their guards they were whipped, and so on and so on. Considering such draconian rules, and the associated opportunities for sadists to indulge their whims, it would stretch credulity to breaking point not to suggest that many of the daily practices of the Spanish Inquisition were more about the emotional high seemingly brought on by crushing the spirit and body of powerless human beings than about routing out heretics and suspected enemies of the state. There has never been anything in the history of mankind more terrifying than self-righteous fanatics, convinced of their own infallibility, and with the power and authority to exercise their will.

This same principal of sadism in ever-increasing doses applies equally to the mob as it does to torture masters and Inquisitors General. From civilization’s earliest hangings through the mass executions of the Spanish Inquisition to the chop, chop, chop of the guillotine during the French Revolution and the cheering, jeering, heaving crowds who brought picnic lunches to see the hangings at London’s Tyburn Tree, crowds love a good display of power and ‘justice’. Satisfying the desire of the masses to see social misfits strung-up or dismembered was the motivating factor in making executions public in the first place – if ‘the people’ didn’t want to witness these things they would have been carried out in private. But the fact is, the multitudes are at least as barbaric as the torture masters, the judges, the Inquisitors and the criminals. The sight of watching people choke on the end of a rope or have their entrails ripped out excites people. When the Duke of Monmouth was beheaded in 1685 for plotting to overthrow his tyrannical uncle, England’s King James II, a crowd of thousands shrieked, screamed and dipped their handkerchiefs in his blood as though he were a holy martyr. They did this because they loved him. Slightly over a century later, when the French Reign of Terror ordered that King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette be led to the guillotine, the reaction was almost identical, but for precisely the opposite reason – Louis they hated, Monmouth they loved, but both executions sent the mob into an ecstatic fervour. Why? For exactly the same reason that torture masters enjoyed their job – pain is both exciting and addictive, and it is this specific aspect of torture and punishment that makes it both so dangerous and so prevalent throughout history. No matter how much societies and governments insist that torture is a legitimate tool for discovering the truth, or for exacting retribution from convicted criminals or imposing the law of God on religious transgressors, the fact remains that it makes both individuals and the state feel good to exercise the ultimate power over those who do not quite fit into society’s accepted mould.

The public execution of the Duke of Monmouth in 1685. This was a ghastly spectacle in which the headsman (Jack Ketch) did a very poor job. According to an eyewitness, ‘the butcherly dog did so barbarously act his part that he could not, at five strokes [of the axe] sever the head from the body.’ Finally, Ketch used his belt knife to sever the Duke’s head from his body.